Abstract

In single site water or hydrocarbon oxidation catalysis with polypyridyl Ru complexes such as [RuII(Mebimpy)(bpy)(H2O)]2+ [where bpy is 2,2′-bipyridine, and Mebimpy is 2,6-bis(1-methylbenzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine] 2, or its surface-bound analog [RuII(Mebimpy)(4,4′-bis-methlylenephosphonato-2,2′-bipyridine)(OH2)]2+ 2-PO3H2, accessing the reactive states, RuV = O3+/RuIV = O2+, at the electrode interface is typically rate limiting. The higher oxidation states are accessible by proton-coupled electron transfer oxidation of aqua precursors, but access at inert electrodes is kinetically inhibited. The inhibition arises from stepwise mechanisms which impose high energy barriers for 1e- intermediates. Oxidation of the RuIII-OH2+ or  forms of 2-PO3H2 to RuIV = O2+ on planar fluoride-doped SnO2 electrode and in nanostructured films of Sn(IV)-doped In2O3 and TiO2 has been investigated with a focus on identifying microscopic phenomena. The results provide direct evidence for important roles for the nature of the electrode, temperature, surface coverage, added buffer base, pH, solvent, and solvent H2O/D2O isotope effects. In the nonaqueous solvent, propylene carbonate, there is evidence for a role for surface-bound phosphonate groups as proton acceptors.

forms of 2-PO3H2 to RuIV = O2+ on planar fluoride-doped SnO2 electrode and in nanostructured films of Sn(IV)-doped In2O3 and TiO2 has been investigated with a focus on identifying microscopic phenomena. The results provide direct evidence for important roles for the nature of the electrode, temperature, surface coverage, added buffer base, pH, solvent, and solvent H2O/D2O isotope effects. In the nonaqueous solvent, propylene carbonate, there is evidence for a role for surface-bound phosphonate groups as proton acceptors.

Keywords: concerted electron-proton transfer, metal oxide electrode, surface modification, electrocatalysis, spectroelectrochemistry

Electron transfer reactions involving pH-dependent proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) couples with a change in proton content between oxidation states, such as quinone/hydroquinone (Q/H2Q) or M = O/M-OH/M-OH2 oxo/hydroxo/aqua transition metal couples, are often slow at inert electrodes (1–5). For these couples, the change in protonation state and the requirement to add or lose protons adds to the normal kinetic barrier to electron transfer. The PCET effect arises from the fact that oxidation or reduction at the electrode occurs by electron transfer without a change in proton content. This effect restricts interfacial mechanisms to electron transfer followed by proton transfer (ET-PT) or proton transfer followed by electron transfer (PT-ET). Both involve high-energy intermediates in nonequilibrium protonation states.

As an example, oxidation of H2Q, H2Q - e- → H2Q+•, occurs at Eo′ = 1.10 V vs. normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) independent of pH (Eo′ is the formal potential) (2). The thermodynamic potential for H2Q oxidation at pH 7, H2Q - e- - H+ → HQ•, is Eo′ = 0.63 V (2). An inert electrode at pH = 7 creates an overpotential of 0.47 V for the initial electron transfer in the ET-PT sequence. Following electron transfer, thermodynamic equilibrium is reached by proton loss from H2Q+• to the surrounding medium at the prevailing pH with ΔEo′ = 1.10 V - 0.059{pH - (pKa(H2Q+•)} with pKa(H2Q+•) = -0.95. Oxidation can also occur by PT-ET with initial loss of a proton from H2Q to give HQ- followed by oxidation to HQ• at Eo′(HQ•/HQ-) = 0.46 V. For this mechanism, an inhibition to rate arises from the pH dependence of the electroactive anion concentration with [HQ-] = Ka[H2Q]T/([H+] + Ka) and [H2Q]T the total concentration of hydroquinone with pKa(H2Q) = 9.85 (2).

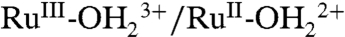

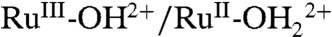

The role of PCET in electrochemical reactivity has been discussed in a series of papers (6–15). In a cyclic voltammetry (CV) study on the Os-based couples cis-[OsIV(bpy)2(py)(O)]2+/cis-[OsIII(bpy)2(py)(OH)]2+ (where bpy is 2,2′-bipyridine) and cis-[OsIII(bpy)2(py)(OH)]2+/cis-[OsII(bpy)2(py)(OH2)]2+, Savéant and coworkers (7) concluded that oxidation of  to OsIII-OH2+ is dominated by ET-PT below pH 7 and by PT-ET above pH 7. The OsIV = O2+/OsIII-OH2+ couple is slower than the

to OsIII-OH2+ is dominated by ET-PT below pH 7 and by PT-ET above pH 7. The OsIV = O2+/OsIII-OH2+ couple is slower than the  couple by approximately 103 with a negligible H2O/D2O solvent kinetic isotope effect (KIE) in acidic solution. Rate accelerations were observed with added proton acceptor bases, the Britton–Robinson buffer (phosphate, citrate, borate, and acetate), accompanied by the appearance of a solvent KIE of 2–2.5. The latter was attributed to concerted electron-proton transfer (EPT) at the electrode with electron transfer to the electrode occurring in concert with proton transfer to the added base form of the buffer (7).

couple by approximately 103 with a negligible H2O/D2O solvent kinetic isotope effect (KIE) in acidic solution. Rate accelerations were observed with added proton acceptor bases, the Britton–Robinson buffer (phosphate, citrate, borate, and acetate), accompanied by the appearance of a solvent KIE of 2–2.5. The latter was attributed to concerted electron-proton transfer (EPT) at the electrode with electron transfer to the electrode occurring in concert with proton transfer to the added base form of the buffer (7).

Although water as the solvent could, in principle, act as a proton acceptor or donor, its participation is limited by its acid-base properties with pKa(H3O+) = -1.74 and pKa(H2O) = 15.7. Concerted EPT pathways involving solvent are favorable only for exceedingly strong acids or bases. Where driving forces are comparable, ET is expected to be favored over EPT due to more complex reaction barriers and slower rates for the latter (2).

Electrocatalysis by deliberate introduction of PCET pathways at modified electrode surfaces has been reported (6–15). This study is important in extending solution reactivity, for example, toward water and hydrocarbon oxidation catalysis, to electrode interfaces in device configurations.

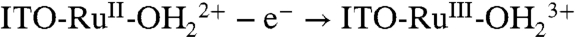

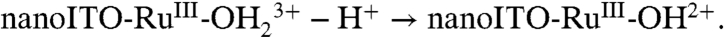

Oxidative activation of carbon electrodes introduces surface quinoidal functional groups which activate PCET couples by enabling concerted EPT pathways at the modified surface (10). For the surface-bound analog of [RuII(tpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ (tpy is 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine) 1, [RuII(tpy)(4,4′-(PO3H2CH2)2bpy)(OH2)]2+ (4,4′-(PO3H2CH2)2bpy is 4,4′-bis-methlylenephosphonato-2,2′-bipyridine) 1-PO3H2, on planar Sn(IV)-doped In2O3 (ITO) electrodes, a reversible RuIV = O2+/RuIII-OH2+ wave appears but only at high surface coverages (11). This observation was attributed to the surface coverage-dependent, cross-surface disproportionation mechanism in Scheme 1. For ITO|1 - PO3H2, initial disproportionation on the surface occurs with ΔGo′ = 0.09 eV. Disproportionation is presumably followed by the ET-PT sequence  ;

;  with ITO-RuIII-OH2+ reentering the disproportionation cycle (11).

with ITO-RuIII-OH2+ reentering the disproportionation cycle (11).

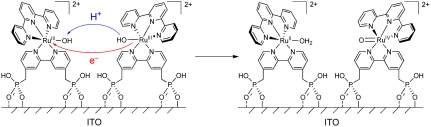

Scheme 1.

Cross-surface disproportionation pathway for accessing RuIV = O2+ at ITO|1-PO3H2 at pH 1 (0.1 M HClO4).

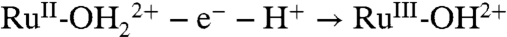

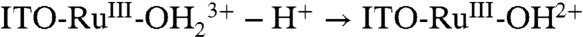

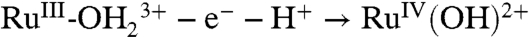

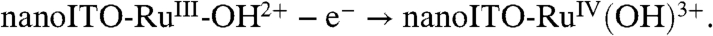

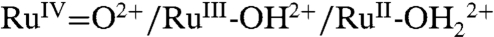

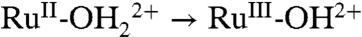

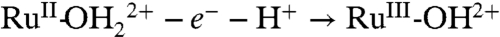

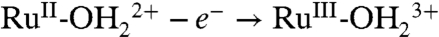

PCET half reactions and EPT pathways play key roles in biological redox reactions (2, 16, 17) and, in a general way, in oxidation-reduction catalysis (2, 18–26). For example, in single site water oxidation catalysis based on polypyridyl Ru complexes such as [RuII(Mebimpy)(bpy)(H2O)]2+ [Mebimpy is 2,6-bis(1-methylbenzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine] 2, or its surface-bound analog [RuII(Mebimpy)(4,4′-(PO3H2CH2)2bpy)(OH2)]2+ 2-PO3H2 (Scheme 2), oxidative activation occurs by sequential e-/H+ transfer:  ; RuIII-OH2+ - e- - H+ → RuIV = O2+ (18–21). PCET oxidation to RuIV = O2+ is followed by oxidation to RuV = O3+ (18–21). Either or both RuIV = O2+ and RuV = O3+ are active as oxidation catalysts. In catalytic cycles based on these oxidants, slow oxidation of RuIII-OH2+ to RuIV = O2+ can contribute to or even dominate rate limiting behavior in electrocatalysis or in photoelectrochemical solar fuels applications.

; RuIII-OH2+ - e- - H+ → RuIV = O2+ (18–21). PCET oxidation to RuIV = O2+ is followed by oxidation to RuV = O3+ (18–21). Either or both RuIV = O2+ and RuV = O3+ are active as oxidation catalysts. In catalytic cycles based on these oxidants, slow oxidation of RuIII-OH2+ to RuIV = O2+ can contribute to or even dominate rate limiting behavior in electrocatalysis or in photoelectrochemical solar fuels applications.

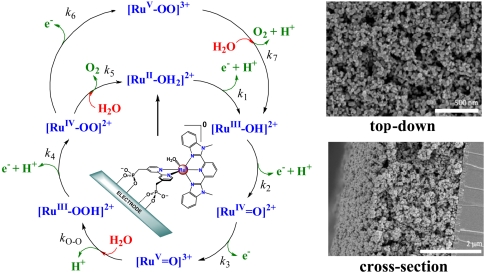

Scheme 2.

Mechanism of water oxidation by 2-PO3H2 on metal oxide electrodes at pH 5 (17).

We report here the results of an investigation on the  couple for surface-bound 2-PO3H2 on planar fluoride-doped SnO2 (FTO), and nanostructured films of ITO (nanoITO) and TiO2 (nanoTiO2). The focus of the study was not on quantitation, but rather on uncovering microscopic phenomena associated with electrochemical interconversion of the two oxidation states. The goal of this research was to establish the mechanism by which surface oxidation and rereduction occur for the surface couple on metal oxide electrodes. Our results demonstrate the kinetic difficulties associated with this couple, identify multiple surface pathways by which it can occur, and assess the roles played by the electrode, temperature, surface coverage, added buffer base, pH, solvent, and solvent H2O/D2O isotope effect.

couple for surface-bound 2-PO3H2 on planar fluoride-doped SnO2 (FTO), and nanostructured films of ITO (nanoITO) and TiO2 (nanoTiO2). The focus of the study was not on quantitation, but rather on uncovering microscopic phenomena associated with electrochemical interconversion of the two oxidation states. The goal of this research was to establish the mechanism by which surface oxidation and rereduction occur for the surface couple on metal oxide electrodes. Our results demonstrate the kinetic difficulties associated with this couple, identify multiple surface pathways by which it can occur, and assess the roles played by the electrode, temperature, surface coverage, added buffer base, pH, solvent, and solvent H2O/D2O isotope effect.

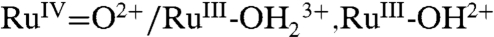

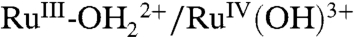

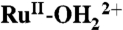

A Pourbaix (E1/2 vs. pH) diagram for 2-PO3H2 on planar FTO electrodes is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S1. It is slightly modified from a previous literature version (18). As a summary of the properties of the couples (22 °C),  ; E1/2(RuIII/II-OH2+/+) ∼ Eo′(RuIII/II-OH2+/+) = 0.29 V;

; E1/2(RuIII/II-OH2+/+) ∼ Eo′(RuIII/II-OH2+/+) = 0.29 V;  ;

;  ; ΔEo′ = ∼ 300 mV for the potential difference between RuIV = O2+/RuIII-OH2+ and

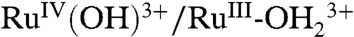

; ΔEo′ = ∼ 300 mV for the potential difference between RuIV = O2+/RuIII-OH2+ and  couples (18). In addition, there is evidence for a protonated form of Ru(IV), RuIV(OH)3+, with pKa ∼ 3 (26).

couples (18). In addition, there is evidence for a protonated form of Ru(IV), RuIV(OH)3+, with pKa ∼ 3 (26).

Results and Discussion

Surface Electrochemistry.

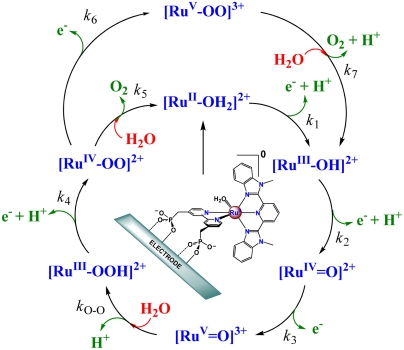

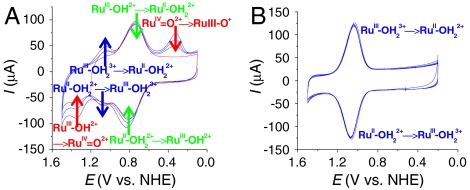

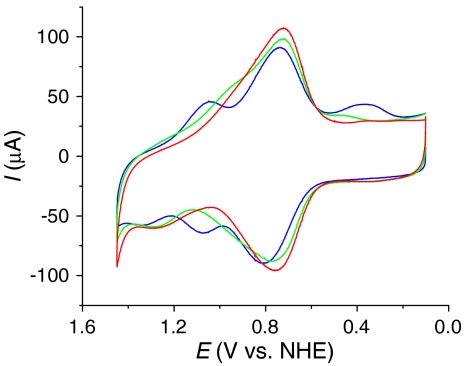

Fig. 1 shows CVs of (A) FTO|2-PO3H2, (B) nanoITO|2-PO3H2, and (C) nanoTiO2|2-PO3H2. All three were obtained at full surface coverages with Γ/Γo = 1 (note Table 1) at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) at 10 mV/s. The surface electrochemistry of the complex on planar ITO is similar to that on planar FTO and is not discussed here. CVs obtained at room temperature, 22 °C, are shown in blue and at 80 °C in red.

Fig. 1.

CVs of (A) FTO|2-PO3H2, (B) nanoITO|2-PO3H2, and (C) nanoTiO2|2-PO3H2 with full surface coverages (Γ/Γo = 1, note Table 1) at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) at 22 °C (blue) and 80 °C (red). Scan rate, 10 mV/s.

Table 1.

Saturated surface coverages for 2-PO3H2 derivatized electrodes

| Electrode | FTO|2-PO3H2 | nanoITO|2-PO3H2 | nanoTiO2|2-PO3H2 |

| Geometric area (cm2)/filmThickness, µm | 1.25/NA | 1.25/approx 2.5 | 1.25/approx 10 |

| Γo, mol/cm2 | 1.2 × 10-10* | 1.7 × 10-8† | 5.3 × 10-8† |

*Determined from the area under the CV wave for the Ru(III/II) couple at 0.68 V vs. NHE at pH 5.

†Calculated from the film absorbance at λmax = 494 nm with εmax = 1.55 × 104 M-1 cm-1 at pH 5 and the expression, Γ = A(λ)/(103 × ε(λ)), with A(λ) and ε(λ) the absorbance and molar absorptivity at 494 nm.

Nature of the electrode.

At 22 °C, 1e- waves appear for the  couple at E1/2 = 0.68 ± 0.01 V with ΔEp( = Ep,a - Ep,c) = 15 mV (FTO), 40 mV (nanoITO), and 105 mV (nanoTiO2) at a scan rate of 10 mV/s. A pH independent RuV = O3+/RuIV = O2+ wave (not shown) appears at approximately 1.65 V, as reported earlier in a study on water oxidation (18). Potential scans to this wave trigger catalytic water oxidation with only the onset shown in Fig. 1.

couple at E1/2 = 0.68 ± 0.01 V with ΔEp( = Ep,a - Ep,c) = 15 mV (FTO), 40 mV (nanoITO), and 105 mV (nanoTiO2) at a scan rate of 10 mV/s. A pH independent RuV = O3+/RuIV = O2+ wave (not shown) appears at approximately 1.65 V, as reported earlier in a study on water oxidation (18). Potential scans to this wave trigger catalytic water oxidation with only the onset shown in Fig. 1.

At FTO and nanoITO, oxidative peak currents (ip,a) for the Ru(II → III) oxidation wave vary linearly with scan rate (υ) as expected for a surface couple (27) (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). By contrast, on nanoTiO2, ip,a varies with the square root of the scan rate (υ1/2) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). A related phenomenon was reported earlier for [Os(bpy)(4,4′-(PO3H2)2bpy)]2+ surface-bound to nanoTiO2 and attributed to Os(II → III) oxidation by cross-surface, diffusional electron transfer (28). In this process, site-to-site electron transfer hopping and counter ion transport occur between surface couples providing a cross-surface electron transfer channel to the underlying electrode.

CV waveforms for RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation at this pH are highly dependent on the nature of the electrode (Fig. 1). At FTO|2-PO3H2 at 10 mV/s, a barely discernible wave or waves appear between 0.9 and 1.3 V (Fig. 1A). Reversal of the potential scan results in Ru(IV → III) rereduction at Ep,c = ∼ 0.83 V. Kinetic inhibition to RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation is shown by the dependence of the current for the Ru(IV → III) rereduction wave on the time held past the Ru(III → IV) wave, either through scan rate variations (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) or by switching potential variations (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

A dramatically different result is obtained for RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation at nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Fig. 1B). At a scan rate of 10 mV/s, a nearly reversible oxidative wave is observed at Ep,a = 1.0 V but of integrated current only approximately 50% of that for the Ru(III/II) wave. For the reverse, Ru(IV → III) reduction, Ep,c = 0.92 V but with a waveform that is noticeably decreased in half-width. Integrated currents for oxidative and reductive waves are comparable.

Both the current and waveform for the Ru(III → IV) wave are strongly dependent on scan rate (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). At 2 mV/s, Ru(III → IV) oxidation is more nearly complete and integrated currents were nearly comparable for the Ru(III → IV) and Ru(II → III) waves. At higher scan rates (50 mV/s), a new, scan-rate-dependent Ru(III → IV) wave appears at Ep,a = 1.28 V at the expense of the wave at Ep,a = 1.0 V. The new wave dominates with further increases in scan rate up to 100 mV/s. In the reverse scan, the narrow waveform for Ru(IV → III) reduction is nearly independent of scan rate but Ep,c shifts negatively with increasing scan rate. The appearance of two Ru(III → IV) oxidation waves and the narrow waveform for Ru(IV → III) reduction are notable observations and will be discussed below.

As shown in Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4, at nanoTiO2|2-PO3H2, kinetic inhibition is complete with no evidence for a wave or waves for Ru(III → IV) oxidation over a range of scan rates. This result is consistent with the slow cross-surface, site-to-site electron transfer hopping observed for the Ru(III/II) couple.

Temperature.

The three electrodes respond differently to an increase in temperature from 22 to 80 °C. At FTO|2-PO3H2 the overall waveform and peak current for the kinetically facile Ru(II → III) oxidation are relatively unaffected, but the peak current for the kinetically inhibited Ru(III → IV) oxidation increases from barely discernible to becoming comparable to the peak current for the Ru(II → III) wave. A similar effect was observed on nanoITO|2-PO3H2 with the Ru(II → III) wave relatively unaffected but the integrated current ratio for the Ru(III → IV) and Ru(II → III) waves increasing from approximately 50% at 22 °C to about 100% at 80 °C at 10 mV/s. At nanoTiO2 the peak current for the Ru(III/II) wave at E1/2 = 0.68 V is significantly enhanced and a kinetically inhibited wave for the Ru(IV/III) couple appears at E1/2 = ∼ 0.9 V. At all three electrodes, the increase in temperature from 22 to 80 °C causes an approximately -40 mV shift in E1/2 for both couples (after accounting for the temperature dependence of the reference electrode). The negative temperature coefficients are consistent with a decrease in entropy for both couples, largely due to solvation of the released proton, e.g.,  (29).

(29).

Surface Loading Effects.

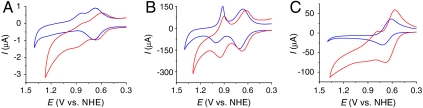

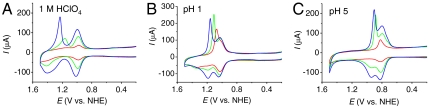

The data in Fig. 2A at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) at 22 °C reveal a surface loading effect on the Ru(III → IV) wave at nanoITO|2-PO3H2 while leaving the waveform for the Ru(III/II) couple unaffected. At low coverages, with the surface dilute in complex (green line, Γ/Γo = 0.1), a Ru(III → IV) oxidation wave appears at Ep,a = ∼ 1.26 V with Ru(IV → III) rereduction occurring at Ep,c = ∼ 0.83 V at 10 mV/s.

Fig. 2.

CVs of nanoITO|2-PO3H2 with (A) Γ/Γo = 0.03 (red), 0.1 (green), 0.25 (blue), 0.4 (cyan), 0.6 (magenta), 0.85 (yellow), 1 (dark yellow) at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-), and (B) Γ/Γo = 0.1 (red), 0.4 (green), 1 (blue) at pH 1 (0.1 M HNO3). Scan rate, 10 mV/s; temperature, 22 °C.

As surface loading is increased to Γ/Γo = 0.25 (blue line), the wave for Ru(III → IV) oxidation at Ep,a = ∼ 1.0 V, observed on the fully loaded surface with Γ/Γo = 1 in Fig. 1, also appears but at the expense of the wave at Ep,a = ∼ 1.26 V. The reverse Ru(IV → III) wave remains narrow in half-width with Ep,c shifting to more positive potentials as surface loading is increased. The switching potential result in SI Appendix, Fig. S6 shows that both oxidations result in the same wave for Ru(IV → III) rereduction at Ep,c = 0.92 V at 10 mV/s. On a fully covered surface, Γ/Γo = 1 (dark-yellow line), only the Ru(III → IV) wave at Ep,a = 1.0 V is observed.

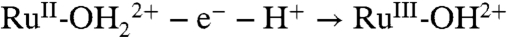

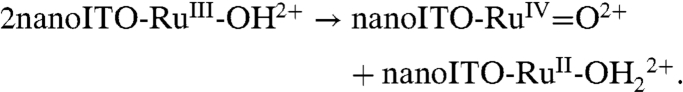

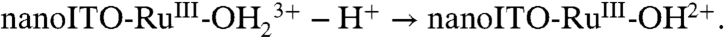

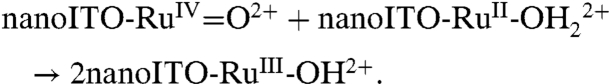

Analysis of these results points to two pathways for Ru(III → IV) oxidation:

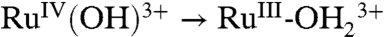

-

At low surface coverages and high scan rates, above the pKa for

, direct oxidation of RuIII-OH2+ to RuIV(OH)3+ occurs at Ep,a ∼ 1.26 V by the ET-PT mechanism in [1]. There is no corresponding RuIV(OH)3+/RuIII-OH2+ rereduction wave at this pH because once RuIV(OH)3+ is formed, it deprotonates rapidly ([1b]). As noted above, pKa ∼ 3 for the equilibrium, RuIV(OH)3+↔RuIV = O2+ + H+. There is no additional characterization data for RuIV(OH)3+ and its structure is uncertain.

, direct oxidation of RuIII-OH2+ to RuIV(OH)3+ occurs at Ep,a ∼ 1.26 V by the ET-PT mechanism in [1]. There is no corresponding RuIV(OH)3+/RuIII-OH2+ rereduction wave at this pH because once RuIV(OH)3+ is formed, it deprotonates rapidly ([1b]). As noted above, pKa ∼ 3 for the equilibrium, RuIV(OH)3+↔RuIV = O2+ + H+. There is no additional characterization data for RuIV(OH)3+ and its structure is uncertain.

[1a]

[1b] This conclusion is reinforced by the surface coverage-independent results at pH 1 (0.1 M HNO3) in Fig. 2B. Under these conditions, a kinetically distorted but chemically reversible Ru(IV/III) couple appears at E1/2 = 1.27 V at 10 mV/s with the Ru(III/II) couple appearing at E1/2 = 0.82 V. For the Ru(IV/III) wave, as for the Ru(III/II) wave, the current increases linearly with surface coverage with the waveform and peak potential nearly independent of surface coverage.

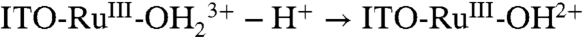

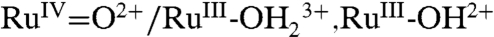

From the E1/2-pH diagram in SI Appendix, Fig. S1,

for surface-bound 2-PO3H2. At pH 1, the Ru(III/II) couple is

for surface-bound 2-PO3H2. At pH 1, the Ru(III/II) couple is  , and the Ru(IV/III) couple is

, and the Ru(IV/III) couple is  .The electrode mechanism for Ru(III → IV) oxidation at pH 1 (0.1 M HNO3) is presumably PT-ET as shown in [2]. In this mechanism, initial deprotonation of

.The electrode mechanism for Ru(III → IV) oxidation at pH 1 (0.1 M HNO3) is presumably PT-ET as shown in [2]. In this mechanism, initial deprotonation of is followed by electron transfer oxidation of RuIII-OH2+ to RuIV(OH)3+. The

is followed by electron transfer oxidation of RuIII-OH2+ to RuIV(OH)3+. The  couple is kinetically inhibited as seen by the increase in ΔEp( = Ep,a - Ep,c) = 140 mV as compared to 25 mV for the

couple is kinetically inhibited as seen by the increase in ΔEp( = Ep,a - Ep,c) = 140 mV as compared to 25 mV for the  wave at 10 mV/s, perhaps indicative of a more significant structural change between RuIV(OH)3+ and RuIII-OH2+ than simple proton transfer.

wave at 10 mV/s, perhaps indicative of a more significant structural change between RuIV(OH)3+ and RuIII-OH2+ than simple proton transfer.

[2a]

[2b] -

Facilitation of Ru(III → IV) oxidation at high surface coverages points to higher order involvement of surface-bound sites. A reasonable origin is oxidation of RuIII-OH2+ to RuIV = O2+ by a disproportionation mechanism, [3], analogous to the mechanism shown in Scheme 1 (11). High loadings and close contact across the surface are required for the proton transfer part of EPT in [3a]. It is short range in nature due to the requirement for vibrational wave function overlap in order for proton tunneling to occur (2,30). Although there is no experimental evidence, the mediation of proton transfer by one or more water molecules may be involved.

[3a]

[3b]

[3c] For the disproportionation step in [3a], ΔGo′ = 0.3 eV for RuIII-OH2+ on nanoITO|2-PO3H2 at pH 5 compared to 0.09 eV for RuIII-OH2+ of 1-PO3H2. This increase contributes to the reaction barrier and decreased rate. The impact of slow kinetics is observed in the appearance of both direct oxidation and disproportionation pathways on fully loaded surfaces at relatively rapid scan rates (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). At these scan rates, oxidation by disproportionation at Ep,a = 1.0 V is incomplete at the thermodynamic potential for the couple. Sites that remain unoxidized during the scan undergo oxidation by direct electron transfer at the potential for the RuIV(OH)3+/RuIII-OH2+ couple followed by proton loss to give RuIV = O2+, [1].

Utilization of both pathways on less than fully loaded surfaces explains the simultaneous appearance of disproportionation and direct oxidation waves in Fig. 2A. Given the anticipated sensitivity to separation distance for disproportionation and the requirement to minimize proton tunneling distances on partly loaded surfaces, there is presumably a distribution of sites in appropriate orientations for disproportionation to occur. Oxidation of separated sites and sites with inappropriate orientations toward neighbors are limited to the direct oxidation pathway.

At high surface coverages on FTO|2-PO3H2 at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-), there is also (barely discernible) evidence for Ru(III → IV) oxidation waves at Ep,a ∼ 1.01 and 1.24 V at 10 mV/s (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). This result points to contributions to Ru(III → IV) oxidation from both direct oxidation and cross-surface disproportionation oxidation pathways, [1] and [3], on planar FTO as well. However, the effect is far more prominent in the three-dimensional nanoITO structure, suggesting a role for the three-dimensional internal cavity structure in the latter. At pH 1 (0.1 M HNO3), as on nanoITO|2-PO3H2, kinetic inhibition of the

couple was also observed with an ill-defined Ru(III → IV) wave appearing at Ep,a = ∼ 1.37 V and Ru(IV → III) rereduction at Ep,c = 1.15 V (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B).

couple was also observed with an ill-defined Ru(III → IV) wave appearing at Ep,a = ∼ 1.37 V and Ru(IV → III) rereduction at Ep,c = 1.15 V (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B).

Base Effect.

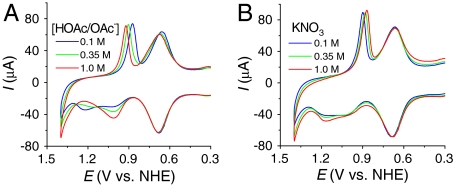

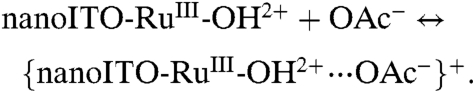

Significant rate accelerations for Ru(III → IV) oxidation are also observed with OAc- added to the external solution as a proton acceptor base. As discussed below, this observation points to a third pathway for RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation, base-assisted, concerted EPT as reported by Savéant and coworkers in the oxidation of cis-[OsIII(bpy)2(py)(OH)]2+ to cis-[OsIV(bpy)2(py)(O)]2+ (7). Illustrative data are shown in Fig. 3A for nanoITO|2-PO3H2 at a surface coverage of Γ/Γo = 0.35. The base effect is present at all surface coverages but is more pronounced at low surface coverages. In these experiments, the total concentration of buffer was increased with pH held constant at pH 5 at the buffer ratio, [OAc-]/[HOAc] = 0.56. Addition of LiCF3SO3 to maintain the ionic strength gave equivalent results.

Fig. 3.

(A) CVs of nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 0.35) at pH 5 with different concentrations of HOAc/NaOAc. (B) CVs of nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 0.40) at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) with addition of increasing amounts of KNO3. Scan rate, 10 mV/s; temperature, 22 °C.

The Ru(III/II) couple is largely unaffected by added buffer in this concentration range. However, increasing the concentration of OAc- results in an increase in ip,a for the RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ wave at Ep,a = 1.0 V at the expense of ip,a for the RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV(OH)3+ wave at Ep,a = 1.26 V. The peak current for RuIV = O2+ → RuIII-OH2+ rereduction is unaffected by added buffer, but Ep,c shifts from 0.87 to 0.92 V as [HOAc/OAc-] was increased from 0.1 to 1.0 M.

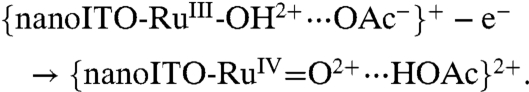

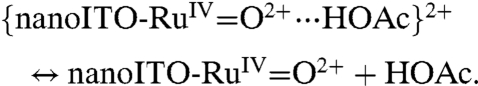

As shown in [4], HOAc/OAc- may play a role in catalysis of the surface-bound Ru(IV/III) couple with preassociation of OAc- to RuIII-OH2+ occurring by a hydrogen bond/ion-pair interaction prior to oxidation (12). The wave for Ru(IV → III) rereduction remains skewed with a narrow half-width. The shift in Ep,c with added HOAc/OAc- at fixed scan rate is consistent with a role for prior association between RuIV = O2+ and HOAc prior to reduction and the Ru(IV/III) couple, {RuIV = O2+⋯HOAc}2+/{RuIII-OH2+⋯OAc-}+ at E1/2 = 0.96 V at pH 5 at 10 mV/s.

|

[4a] |

|

[4b] |

|

[4c] |

The importance of preliminary ion pairing is shown by the influence of added KNO3 (Fig. 3B). In these experiments, CVs of nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 0.40) at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) with increasing amounts of added KNO3 were obtained at 10 mV/s. Under these conditions, the ratio of peak currents for the two oxidative waves, ip,a(1.0 V)/ip,a(1.26 V), decreases as  is increased from 0 to 1 M. The implied conversion in surface mechanism from EPT with OAc- as acceptor base to direct oxidation is consistent with a generalized ion atmosphere effect and/or replacement of OAc- by

is increased from 0 to 1 M. The implied conversion in surface mechanism from EPT with OAc- as acceptor base to direct oxidation is consistent with a generalized ion atmosphere effect and/or replacement of OAc- by  at the ion paired surface cation (7). Ep,c for Ru(IV → III) rereduction also shifts negatively with increasing

at the ion paired surface cation (7). Ep,c for Ru(IV → III) rereduction also shifts negatively with increasing  because of competitive ion pairing with

because of competitive ion pairing with  .

.

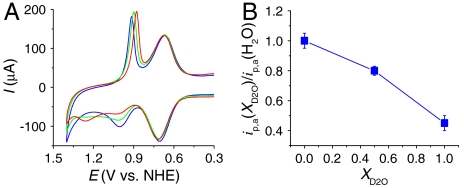

H2O/D2O Kinetic Isotope Effects.

At pH 5, notable H2O/D2O isotope effects appear for the Ru(III → IV) wave on nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1), whereas the Ru(II → III) wave is essentially unaffected (Fig. 4). In D2O, ip,a for RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation at Ep,a = 1.0 V is greatly decreased, whereas ip,a for direct RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV(OH)3+ oxidation at Ep,a = 1.26 V is increased.

Fig. 4.

(A) CVs of nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1) at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) in H2O (blue), 1∶1 H2O/D2O (green), and D2O (red). (B) Dependence of ip,a(XD2O)/ip,a(H2O, XD2O = 0) at 1.0 V (background subtracted) on XD2O. Scan rate, 10 mV/s; temperature, 22 °C.

The isotopic discrimination between pathways is a reflection of surface mechanism. As shown by measurements at pH 1 in SI Appendix, Fig. S8, there is essentially no KIE for direct RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV(OH)3+ oxidation with ip,a(H2O)/ip,a(D2O) = ∼ 1 independent of surface coverage. By contrast, at pH 5 for the wave at Ep,a = 1.0 V in Fig. 4A, ip,a(H2O)/ip,a(D2O) = ∼ 2.4 comparable to the KIE observed for oxidation of cis-[OsIII(bpy)2(py)(OH)]2+ with added buffer bases (7).

At pH 5, there are two mechanistic contributors to the wave for RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation at Ep,a = 1.0 V. Cross-surface disproportionation, [3], is dominant with an additional contribution from the EPT pathway in [4]. Participation by two pathways appears in the nonlinearity of the plot of ip,a vs. mole fraction of D2O (XD2O) (Fig. 4B). A linear relationship is predicted for a single pathway with a single proton transferred (2). At a lower surface coverage, Γ/Γo = 0.60, where EPT should play a greater role, KIE = ∼ 3.6.

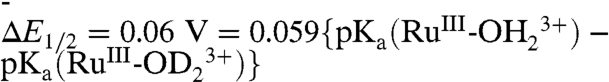

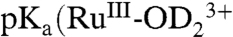

As noted above, at pH 1, electron transfer dominates with KIE = ∼ 1. There is a slight but noticeable shift in E1/2 for this wave from 1.27 V at XD2O = 0 to 1.33 V at XD2O = 1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Given the proton content change for the  couple at this pH, the shift in E1/2, ΔE1/2 is dominated by the proton equilibrium in [2a]. In this limit,

couple at this pH, the shift in E1/2, ΔE1/2 is dominated by the proton equilibrium in [2a]. In this limit,  . With

. With  (SI Appendix, Fig. S1),

(SI Appendix, Fig. S1),  ) is estimated to be 1.3.

) is estimated to be 1.3.

Rereduction of RuIV = O2+.

For nanoITO|2-PO3H2 or FTO|2-PO3H2 in acidic solution, a kinetically inhibited, but normal wave shape is observed for  rereduction at E1/2 = 1.27 V. Under these conditions, the mechanism for rereduction is ET-PT, the reverse of [2].

rereduction at E1/2 = 1.27 V. Under these conditions, the mechanism for rereduction is ET-PT, the reverse of [2].

At higher pHs, with pH > pKa(RuIV(OH)3+), the equilibrium concentration of RuIV(OH)3+ is reduced and rereduction by ET-PT, the reverse of [2], becomes insignificant. Under these conditions, Ru(IV → III) rereduction occurs by a skewed, narrow wave at lower potentials. Its Ep,c value is dependent on surface loading, scan rate, and base concentration.

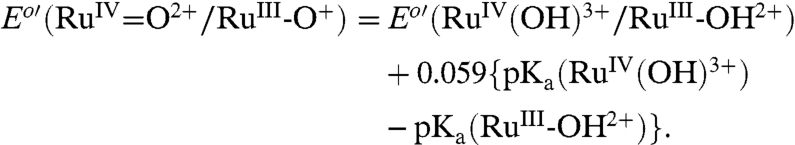

Rereduction of RuIV = O2+ is constrained to occur by ET-PT with reduction to RuIII-O+ followed by rapid protonation of RuIII-O+, [5a] and [5b]. The thermodynamic potential for the RuIV = O2+/RuIII-O+ couple can be estimated from Eq. 6 and the difference in pKa values between RuIV(OH)3+ and RuIII-OH2+. Given that, Eo′(RuIV(OH)3+/RuIII-OH2+) = 1.27 V, and assuming pKa(RuIV(OH)3+) ≈ 3 and pKa(RuIII-OH2+) > 14, Eo′(RuIV = O2+/RuIII-O+) is estimated to be < 0.62 V. Based on this estimate for Eo′(RuIV = O2+/RuIII-O+) and the data in Fig. 2A, reduction at Ep,c = ∼ 0.83 V at Γ/Γo = 0.1 (green line) at 10 mV/s occurs with an underpotential of > 0.21 V.

| [5a] |

| [5b] |

| [5c] |

|

[5d] |

|

[6] |

From the surface loading dependence in Fig. 2A, there also appears to be an autocatalytic effect triggered by partial reduction arising from cross-surface comproportionation, [5c] and [5d]. With RuIII-OH2+ formed by ET-PT reduction of RuIV = O2+, [5a] and [5b], a basis for autocatalysis exists by further reduction to  and cross-surface comproportionation with the remaining RuIV = O2+ sites on the surface, [5c] and [5d]. As shown by the CV simulations in SI Appendix, Fig. S9 and Table S1, an analogous mechanism for the solution

and cross-surface comproportionation with the remaining RuIV = O2+ sites on the surface, [5c] and [5d]. As shown by the CV simulations in SI Appendix, Fig. S9 and Table S1, an analogous mechanism for the solution  couples of 2 at pH 5 reproduces the narrow wave shape observed for the surface couple.

couples of 2 at pH 5 reproduces the narrow wave shape observed for the surface couple.

Propylene Carbonate as Solvent.

In propylene carbonate (PC) with added water (PC∶H2O, water miscibility < 8%, vol∶vol), both 2 and its surface analog, nanoITO|2-PO3H2, are known water oxidation catalysts by the mechanism in Scheme 2 (31). There is evidence for continued coordination of H2O based on the UV-visible spectra of 2 in solution (31) and for 2-PO3H2 on nanoITO (see below).

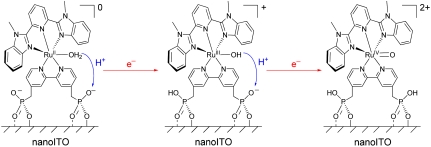

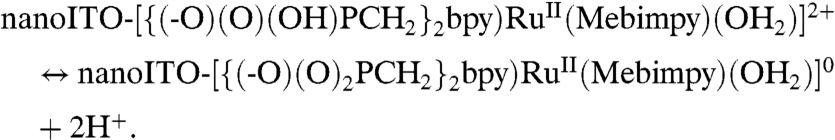

There is also evidence for surface PCET effects based on the surface-bound phosphonate groups with pKa ∼ 1–2 for proton loss in water (12, 32). The procedure for surface attachment of 2-PO3H2, described in Materials and Methods (“as prepared”), involved soaking the complex for extended periods at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) followed by rinsing with distilled water, conditions under which deprotonation of the phosphonates occurs to give nanoITO-[{(-O)(O)2PCH2}2bpy)RuII(Mebimpy)(OH2)]0 on the surface, [7] (12, 32). In aqueous solutions, proton equilibration between the surface-bound phosphonate groups and the external solution occurs rapidly. In dry PC, the surface proton composition is fixed and, as shown below, impacts CVs for both Ru(IV/III) and Ru(III/II) couples:

|

[7] |

A CV for an as-prepared nanoITO|2-PO3H2 slide is shown in Fig. 5A in 0.1 M LiClO4/PC at 10 mV/s. In the first scan, a wave for a Ru(III/II) couple appears, but at E1/2 = 0.78 V (ΔEp = 90 mV) with a relatively small, irreversible Ru(III → IV) wave at Ep,a = 1.33 V. The potential difference between Ru(II → III) and Ru(III → IV) waves is ΔEp,a ∼ 500 mV, which is comparable to ΔEp,a ∼ 400 mV between  and RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidations at pH 5, suggesting a common origin.

and RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidations at pH 5, suggesting a common origin.

Fig. 5.

(A) Successive CVs (three cycles) of as-prepared nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1) in 0.1 M LiClO4/PC. The arrows indicate the current variations upon successive potential scans. Red line, potential scan reversal before Ep,a = 1.33 V. (B) Successive CVs (five cycles) of acid-treated nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1) in 0.1 M LiClO4/PC. Scan rate, 10 mV/s; temperature, 22 °C.

Following successive scans through the RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ wave accompanied by proton release, a new Ru(III/II) couple appears at E1/2 = 1.06 V (ΔEp = 40 mV). This wave arises from the  couple (see below), with its E1/2 value increased by 240 mV compared to E1/2 = 0.82 V for the same couple in 0.1 M HNO3 (Fig. 2B). Appearance of the

couple (see below), with its E1/2 value increased by 240 mV compared to E1/2 = 0.82 V for the same couple in 0.1 M HNO3 (Fig. 2B). Appearance of the  couple is accompanied by decreases in peak currents for the

couple is accompanied by decreases in peak currents for the  couple at E1/2 = 0.78 V and the RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ wave at Ep,a = 1.33 V.

couple at E1/2 = 0.78 V and the RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ wave at Ep,a = 1.33 V.

A CV for an “acid treated” nanoITO|2-PO3H2 slide is shown in Fig. 5B. In the acid treatment, an as-prepared slide was soaked in a 0.1 M HClO4 aqueous solution for 30 s followed by drying in a N2 gas stream. In the resulting CV in 0.1 M LiClO4/PC at 10 mV/s, a wave for the  couple appears at E1/2 = 1.06 V (ΔEp = 40 mV) with no evidence for further oxidation to RuIV = O2+ through a series of five successive scans. Surface oxidation of

couple appears at E1/2 = 1.06 V (ΔEp = 40 mV) with no evidence for further oxidation to RuIV = O2+ through a series of five successive scans. Surface oxidation of  to

to  rather than RuIII-OH2+ is the expected result in a nonaqueous solvent with a significant decrease in proton acidity for

rather than RuIII-OH2+ is the expected result in a nonaqueous solvent with a significant decrease in proton acidity for  due to loss of hydration free energy for the proton (33).

due to loss of hydration free energy for the proton (33).

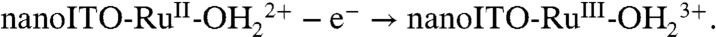

An explanation is available for the difference in behaviors between as-prepared and acid-treated slides and the appearance of the proton-dependent  and RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ waves based on PCET involvement by basic sites on the surface or, more likely, the surface-bound, phosphonate groups with pKa ∼ 1–2. The deprotonated phosphonate groups on as-prepared slides presumably act as proton acceptors for

and RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ waves based on PCET involvement by basic sites on the surface or, more likely, the surface-bound, phosphonate groups with pKa ∼ 1–2. The deprotonated phosphonate groups on as-prepared slides presumably act as proton acceptors for  oxidation with proton transfer to a surface phosphonate group (step 1 in Scheme 3). The

oxidation with proton transfer to a surface phosphonate group (step 1 in Scheme 3). The  couple is kinetically inhibited, presumably because of the requirements imposed on proton transfer by orientation and proton transfer distance. Kinetic inhibition is seen in the increase in ΔEp from 40 mV for the same couple at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) in water compared to 90 mV in PC and by the scan rate dependence of the couple (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). At fast scan rates,

couple is kinetically inhibited, presumably because of the requirements imposed on proton transfer by orientation and proton transfer distance. Kinetic inhibition is seen in the increase in ΔEp from 40 mV for the same couple at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) in water compared to 90 mV in PC and by the scan rate dependence of the couple (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). At fast scan rates,  oxidation is incomplete at the thermodynamic potential for the couple. Sites that remain unoxidized at Ep,a = 0.83 V undergo

oxidation is incomplete at the thermodynamic potential for the couple. Sites that remain unoxidized at Ep,a = 0.83 V undergo  oxidation at Ep,a = 1.08 V.

oxidation at Ep,a = 1.08 V.

Scheme 3.

Proposed interfacial proton transfer to surface phosphonate groups in the oxidation of  to RuIV = O2+ in PC as solvent.

to RuIV = O2+ in PC as solvent.

Given the proton stoichiometry in [7], an additional deprotonated phosphonate site is available at as-prepared slides for further oxidation and proton loss, enabling access to RuIV = O2+ (step 2 in Scheme 3), which would explain the appearance of the wave at Ep,a = 1.33 V as due to RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation. Oxidation occurs only through RuIII-OH2+ and not through  as shown by the absence of a Ru(III → IV) wave for the acid-treated slide in Fig. 5B. Surface-bound phosphonates may also play a role in the aqueous solution electrochemistry of the surface-bound Ru(IV/III) couple but with no evidence for it in our data.

as shown by the absence of a Ru(III → IV) wave for the acid-treated slide in Fig. 5B. Surface-bound phosphonates may also play a role in the aqueous solution electrochemistry of the surface-bound Ru(IV/III) couple but with no evidence for it in our data.

The  wave appears for as-prepared slides only on successive oxidative scans (Fig. 5A). It appears to be triggered by RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation and proton release. Presumably, partial protonation of surface phosphonate sites inhibits

wave appears for as-prepared slides only on successive oxidative scans (Fig. 5A). It appears to be triggered by RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation and proton release. Presumably, partial protonation of surface phosphonate sites inhibits  oxidation with unoxidized sites undergoing

oxidation with unoxidized sites undergoing  oxidation at Ep,a = 1.08 V.

oxidation at Ep,a = 1.08 V.

The phenomena reported in Fig. 5 are independent of surface loading with closely related observations made at Γ/Γo = 0.2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). There is no evidence for cross-surface disproportionation in PC as solvent, presumably because the PCET-phosphonate pathways in Scheme 3 are kinetically more facile and dominate electron transfer reactivity of the surface Ru(IV/III) couple.

As shown by the switching potential variations in Fig. 5A, in PC, in the absence of a ready supply of protons, rereduction of RuIV = O2+ to RuIII-O+ occurs at Ep,c = 0.34 V at 10 mV/s. This value is consistent with Eo′ < 0.62 V estimated for the RuIV = O2+/RuIII-O+ couple in water by use of Eq. 6. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S12 and Table S2, CV simulations of 2 in PC based on a mechanism involving RuIV = O2+ → RuIII-O+ reduction reproduces the RuIV = O2+ → RuIII-O+ waveform.

Both potential and peak current for RuIV = O2+ → RuIII-O+ rereduction are scan-rate dependent (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). As the scan rate is decreased, Ep,c shifts positively and the current ratio ip,c(0.34 V)/ip,a(1.33 V) decreases. These observations are qualitatively consistent with protonation of RuIII-O+ by trace water or protonated surface phosphonate following reduction of RuIV = O2+ at slow scan rates.

The influence of added water on CVs of nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1) in 0.1 M LiClO4/PC is illustrated in Fig. 6. Increasing water from 0% to 6% (vol∶vol) causes a decrease in E1/2 for the  couple from 0.78 to 0.73 V, presumably due to a generalized solvation effect. The peak currents for the

couple from 0.78 to 0.73 V, presumably due to a generalized solvation effect. The peak currents for the  couple also grow at the expense of ip for the

couple also grow at the expense of ip for the  couple, presumably due to the PCET couple being favored by enhanced solvation of the released proton.

couple, presumably due to the PCET couple being favored by enhanced solvation of the released proton.

Fig. 6.

CVs of nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1) in 0.1 M LiClO4/PC with addition of 0% (blue), 1% (green), and 6% (red) water. Scan rate, 10 mV/s; temperature, 22 °C.

Solvation also affects RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation with Ep,a = 1.33 V (0% H2O) shifting to 1.28 V (6% H2O). The influence of water is more profound on the RuIV = O2+ → RuIII-O+ reduction wave because of rapid protonation of RuIII-O+ once it is formed with Ep,c shifting to 0.46 V with 1% added water. At 6% added water, this wave is shifted more positively and masked by the  reduction wave.

reduction wave.

Comparisons with nanoITO|1-PO3H2.

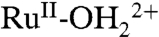

CV measurements were extended to the Ru(IV/III) couple of 1-PO3H2 on nanoITO. As noted in the Introduction, ΔEo′ = 0.09 V between the Ru(IV/III) and Ru(III/II) couples for 1-PO3H2 from pH 1 to pH 10. The  form of 1-PO3H2 is more acidic than 2-PO3H2 with

form of 1-PO3H2 is more acidic than 2-PO3H2 with  (11).

(11).

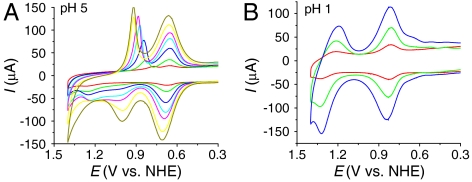

In Fig. 7 are shown CVs of nanoITO|1-PO3H2 at three different surface loadings in three different media. For the surfaces with Γ/Γo ≤ 0.4 in 1 M HClO4 (red and green lines in Fig. 7A), a chemically reversible but kinetically distorted wave appears for the Ru(IV/III) couple at E1/2 = 1.28 V. This wave appears at the expected E1/2 value for the  couple for 1-PO3H2 at this pH. On these dilute surfaces, a reasonable mechanism for

couple for 1-PO3H2 at this pH. On these dilute surfaces, a reasonable mechanism for  oxidation is PT-ET, as proposed in [2] for 2-PO3H2.

oxidation is PT-ET, as proposed in [2] for 2-PO3H2.  rereduction at 10 mV/s occurs at Ep,c = 1.17 V with a relatively normal wave shape, but the couple is kinetically inhibited with ΔEp = 230 mV.

rereduction at 10 mV/s occurs at Ep,c = 1.17 V with a relatively normal wave shape, but the couple is kinetically inhibited with ΔEp = 230 mV.

Fig. 7.

CVs of nanoITO|1-PO3H2 with (A) Γ/Γo = 0.1 (red), 0.4 (green), 1 (blue) in 1 M HClO4, (B) Γ/Γo = 0.25 (red), 0.6 (green), 1 (blue) at pH 1 (0.1 M HClO4), and (C) Γ/Γo = 0.1 (red), 0.6 (green), 1 (blue) at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-). Scan rate, 10 mV/s; temperature, 22 °C.

On a completely loaded surface (Γ/Γo = 1) (blue line in Fig. 7A), there is evidence for dual pathways based on the appearance of a new wave at Ep,a = ∼ 1.30 V at 10 mV/s. The surface loading dependence is consistent with the disproportionation mechanism in [3] and the appearance of dual pathways to a competition between disproportionation in [3] and direct oxidation in [2]. On the reverse scan, a narrow rereduction wave appears at Ep,a = 1.23 V (blue line in Fig. 7A). The wave shape is similar to that for rereduction of RuIV = O2+ for 2-PO3H2 at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) and the autocatalytic mechanism in [5].

At pH 1 (0.1 M HClO4) at 10 mV/s, there is clearer evidence for surface loading-dependent, dual pathways for Ru(III → IV) oxidation with waves appearing at Ep,a = 1.36 and 1.19 V (Fig. 7B and SI Appendix, Fig. S13). For the wave at Ep,a = 1.19, ip,a increases as surface coverage is increased, consistent with disproportionation in competition with direct oxidation. The disproportionation pathway dominates at Γ/Γo = 1. A single, narrow, surface loading-dependent rereduction wave appears with Ep,c = 1.16 V at Γ/Γo = 1, consistent with autocatalytic comproportionation, [5].

Related phenomena were observed at pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-) at 10 mV/s. A wave for direct Ru(III → IV) oxidation appears at Ep,a = 1.33 V (Γ/Γo ≤ 0.1) (the CV in red in Fig. 7C with a magnified view in SI Appendix, Fig. S14). At higher surface coverages, disproportionation dominates with RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation occurring at Ep,a = 0.98 V. Reverse, Ru(IV → III) rereduction also occurs by a single, narrow, surface loading-dependent wave with Ep,c = 0.90 V at Γ/Γo = 1. As noted above, disproportionation is expected to play a more important role than at nanoITO|2-PO3H2 because of the small driving force (ΔG = +0.09 eV) for RuIII-OH2+ disproportionation.

As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S15, CVs of nanoITO|2-PO3H2 in 0.1 M LiClO4/PC have the same features as described for nanoITO|1-PO3H2, consistent with participation by the surface-bound phosphonate groups in PCET half reactions.

Real Time Spectrophotometric Study.

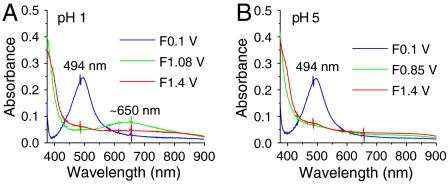

The use of optically transparent, conductive, high surface area nanoITO allows for the acquisition of UV-visible spectral data of electrochemically generated intermediates and for direct spectral monitoring of voltammograms (34, 35). Fig. 8 shows spectra acquired for nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1) at a series of potentials during CV scans (see Fig. 2). CV scans at fixed wavelengths are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S16.

Fig. 8.

UV-visible spectra of nanoITO|1-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1) scanned to different potentials as indicated (F, forward scan; see Fig. 2). Solution, (A) pH 1 (0.1 M HNO3), (B) pH 5 (0.1 M HOAc/OAc-). Scan rate, 10 mV/s; temperature, 22 °C.

In 0.1 M HNO3 (Fig. 8A), potential scans to 1.08 V, past E1/2 = 0.82 V for Ru(II → III) oxidation, results in loss of the λmax = 494 nm metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) absorption, a characteristic feature for surface-bound  . A ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) absorption for

. A ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) absorption for  appears at λmax = ∼ 650 nm with an increase in absorbance at 400 nm. A further increase in potential to 1.4 V, past E1/2 = 1.27 V for Ru(III → IV) oxidation, results in a broad absorption at approximately 500 nm for RuIV(OH)3+ and the appearance of a shoulder at approximately 400 nm, which appear concomitantly with the disappearance of the absorption of

appears at λmax = ∼ 650 nm with an increase in absorbance at 400 nm. A further increase in potential to 1.4 V, past E1/2 = 1.27 V for Ru(III → IV) oxidation, results in a broad absorption at approximately 500 nm for RuIV(OH)3+ and the appearance of a shoulder at approximately 400 nm, which appear concomitantly with the disappearance of the absorption of  . These spectral changes are consistent with those obtained for stepwise oxidation of [RuII(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ to

. These spectral changes are consistent with those obtained for stepwise oxidation of [RuII(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ to  and then to RuIV(OH)3+ by incremental addition of Ce(IV) in 0.1 M HNO3 (20, 21). The spectra and spectral changes are reversible through multiple scans (SI Appendix, Fig. S16A).

and then to RuIV(OH)3+ by incremental addition of Ce(IV) in 0.1 M HNO3 (20, 21). The spectra and spectral changes are reversible through multiple scans (SI Appendix, Fig. S16A).

In 0.1 M HOAc/OAc- at pH 5 (Fig. 8B), scans past E1/2 = 0.68 V for the Ru(III/II) couple result in loss of the  absorption at λmax = 494 nm, consistent with oxidation to RuIII-OH2+. The latter is relatively featureless in the visible but increases in absorbance at approximately 400 nm. A further increase in potential to 1.4 V, past E1/2 for the Ru(IV/III) couple, results in growth of the approximately 500 nm absorbance and approximately 400 nm shoulder for RuIV = O2+. Reversal of the potential scan from 1.4 to 0.1 V results in complete recovery of the original spectrum (SI Appendix, Fig. S16B).

absorption at λmax = 494 nm, consistent with oxidation to RuIII-OH2+. The latter is relatively featureless in the visible but increases in absorbance at approximately 400 nm. A further increase in potential to 1.4 V, past E1/2 for the Ru(IV/III) couple, results in growth of the approximately 500 nm absorbance and approximately 400 nm shoulder for RuIV = O2+. Reversal of the potential scan from 1.4 to 0.1 V results in complete recovery of the original spectrum (SI Appendix, Fig. S16B).

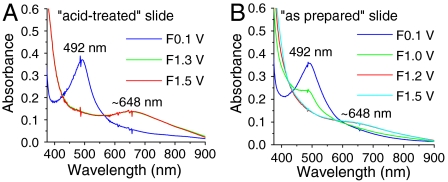

Fig. 9 shows spectra at nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1) obtained at fixed potentials during CV scans (see Fig. 5) in 0.1 M LiClO4/PC. CV scans monitored at fixed wavelengths are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S17. The spectral profiles obtained for  and

and  in PC are consistent with profiles in water but with λmax blue shifted by approximately 2 nm because of a generalized solvent effect.

in PC are consistent with profiles in water but with λmax blue shifted by approximately 2 nm because of a generalized solvent effect.

Fig. 9.

UV-visible spectra of (A) acid-treated and (B) as-prepared nanoITO|2-PO3H2 (Γ/Γo = 1) in 0.1 M LiClO4/PC scanned to different potentials as indicated (F, forward scan; see Fig. 5). Scan rate, 10 mV/s; temperature, 22 °C.

At the acid-treated slide in Fig. 9A, with surface potential scanned to 1.3 V, past E1/2 = 1.06 V for the Ru(III/II) couple in PC, the MLCT absorption for  at λmax = 492 nm decreases with an increase in LMCT absorption for

at λmax = 492 nm decreases with an increase in LMCT absorption for  at λmax = ∼ 648 nm, consistent with oxidation from

at λmax = ∼ 648 nm, consistent with oxidation from  to

to  . There were no further spectral changes upon increasing the potential to 1.5 V, consistent with the inaccessibility of RuIV = O2+ on the acid-treated slide. Reversal of the potential scan from 1.5 to 0.1 V results in complete recovery of the original spectrum (SI Appendix, Fig. S17A).

. There were no further spectral changes upon increasing the potential to 1.5 V, consistent with the inaccessibility of RuIV = O2+ on the acid-treated slide. Reversal of the potential scan from 1.5 to 0.1 V results in complete recovery of the original spectrum (SI Appendix, Fig. S17A).

The spectral evolution of an as-prepared slide in PC as solvent is complicated by participation by both the  and

and  couples and by RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation (Fig. 9B). With the surface potential scanned to 1.0 V, past E1/2 = ∼ 0.78 V for the

couples and by RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation (Fig. 9B). With the surface potential scanned to 1.0 V, past E1/2 = ∼ 0.78 V for the  couple, the MLCT absorption at λmax = 492 nm decreases partially with no evidence for

couple, the MLCT absorption at λmax = 492 nm decreases partially with no evidence for  at λmax = ∼ 648 nm, consistent with oxidation to RuIII-OH2+. Increasing the potential to 1.2 V, past E1/2 = ∼ 1.06 V for the

at λmax = ∼ 648 nm, consistent with oxidation to RuIII-OH2+. Increasing the potential to 1.2 V, past E1/2 = ∼ 1.06 V for the  couple, results in further loss of the MLCT absorption band at λmax = 492 nm concomitant with appearance of the LMCT band at λmax = ∼ 648 nm for

couple, results in further loss of the MLCT absorption band at λmax = 492 nm concomitant with appearance of the LMCT band at λmax = ∼ 648 nm for  , consistent with oxidation of the remaining

, consistent with oxidation of the remaining  sites to

sites to  . A further increase in potential to 1.5 V, past Ep,a = ∼ 1.33 V for RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation results in a slight growth at λ = ∼ 400–500 nm for RuIV = O2+ as observed in aqueous solution. In the additional oxidation to RuIV = O2+, the LMCT absorption at λmax = 648 nm for

. A further increase in potential to 1.5 V, past Ep,a = ∼ 1.33 V for RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV = O2+ oxidation results in a slight growth at λ = ∼ 400–500 nm for RuIV = O2+ as observed in aqueous solution. In the additional oxidation to RuIV = O2+, the LMCT absorption at λmax = 648 nm for  is nearly unaffected, consistent with oxidation from RuIII-OH2+ to RuIV = O2+, but not from

is nearly unaffected, consistent with oxidation from RuIII-OH2+ to RuIV = O2+, but not from  . This result is consistent with the CV result described in the previous section. The fixed wavelength spectral evolution shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S17B reveals a series of spectral changes for the MLCT absorption band at λmax = 492 nm, consistent with the sequence of electrochemical/chemical events suggested in the figure.

. This result is consistent with the CV result described in the previous section. The fixed wavelength spectral evolution shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S17B reveals a series of spectral changes for the MLCT absorption band at λmax = 492 nm, consistent with the sequence of electrochemical/chemical events suggested in the figure.

Conclusions

The overall water oxidation cycle in Scheme 2 consists of a linear sequence of reactions. In order to maximize rates, it is essential that activation barriers for the key rate limiting step or steps be minimized. For water oxidation in Scheme 2, a potential kinetic bottleneck appears in the oxidative activation sequence from  to RuV = O3+ in the

to RuV = O3+ in the  , RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV(OH)3+, RuIV = O2+ stage. Its origin is PCET and the significant change in pKa that exists between RuIII-OH2+ and RuIV(OH)3+. In an overall catalytic scheme, slow rates for this step could compete with the O⋯O bond-forming step between RuV = O3+ and H2O and limit catalytic rates and efficiencies. The results presented here highlight the origin of kinetic inhibitions and provide insights into how to overcome them.

, RuIII-OH2+ → RuIV(OH)3+, RuIV = O2+ stage. Its origin is PCET and the significant change in pKa that exists between RuIII-OH2+ and RuIV(OH)3+. In an overall catalytic scheme, slow rates for this step could compete with the O⋯O bond-forming step between RuV = O3+ and H2O and limit catalytic rates and efficiencies. The results presented here highlight the origin of kinetic inhibitions and provide insights into how to overcome them.

Oxidative activation of RuIII-OH2+ (in proton equilibrium with

) to RuIV(OH)3+ can occur by PT-ET. A pH-dependent overpotential exists for this pathway. It arises from the difference in E1/2 values between the RuIV(OH)3+/RuIII-OH2+ and RuIV = O2+/RuIII-OH2+ couples.

) to RuIV(OH)3+ can occur by PT-ET. A pH-dependent overpotential exists for this pathway. It arises from the difference in E1/2 values between the RuIV(OH)3+/RuIII-OH2+ and RuIV = O2+/RuIII-OH2+ couples.On highly loaded surfaces, cross-surface disproportionation of RuIII-OH2+ occurs to give RuIV = O2+. Disproportionation is followed by oxidation of

on the surface and proton equilibration by

on the surface and proton equilibration by  . The kinetic facility of this pathway is dictated, in part, by the difference in E1/2 values between the RuIV = O2+/RuIII-OH2+ and

. The kinetic facility of this pathway is dictated, in part, by the difference in E1/2 values between the RuIV = O2+/RuIII-OH2+ and  couples.

couples.Concerted EPT with added acid-base buffer pairs like HOAc/OAc- can facilitate RuIII-OH2+↔RuIV = O2+ interconversion by avoiding RuIII-O+ and RuIV(OH)3+ as high-energy intermediates.

As shown by both CV and spectroelectrochemical results, in propylene carbonate, access to RuIV = O2+ depends on the initial protonation state of the phosphonate groups at the electrode surface. With these sites protonated, oxidation stops at

and there is no access to RuIV = O2+. With deprotonated phosphonates at the surface, partial oxidation of

and there is no access to RuIV = O2+. With deprotonated phosphonates at the surface, partial oxidation of  to RuIII-OH2+ occurs with proton transfer to a phosphonate. Oxidation to RuIII-OH2+ is followed by further oxidation to RuIV = O2+ and proton transfer to a phosphonate. For a second fraction of surface

to RuIII-OH2+ occurs with proton transfer to a phosphonate. Oxidation to RuIII-OH2+ is followed by further oxidation to RuIV = O2+ and proton transfer to a phosphonate. For a second fraction of surface  sites, proton transfer is inhibited on the CV timescale and oxidation gives

sites, proton transfer is inhibited on the CV timescale and oxidation gives  with no further oxidation to RuIV = O2+.

with no further oxidation to RuIV = O2+.

RuIV = O2+ rereduction presents related mechanistic challenges:

Reduction of RuIV(OH)3+ to

can occur by ET-PT with RuIV(OH)3+ reduction to RuIII-OH2+ followed by proton equilibration to

can occur by ET-PT with RuIV(OH)3+ reduction to RuIII-OH2+ followed by proton equilibration to  . In water, this pathway only appears in relatively strongly acidic solutions where there is a kinetically significant concentration of RuIV(OH)3+.

. In water, this pathway only appears in relatively strongly acidic solutions where there is a kinetically significant concentration of RuIV(OH)3+.Underpotential reduction of RuIV = O2+ occurs without initial protonation by narrow, kinetically skewed waves. At high surface coverages, autocatalytic reduction of RuIV = O2+ occurs by partial reduction to RuIII-O+ followed by rapid protonation, further reduction to

, and cross-surface comproportionation.

, and cross-surface comproportionation.In PC with no added water, direct RuIV = O2+ → RuIII-O+ reduction occurs at Ep,c = 0.34 V at 10 mV/s by a wave that shifts to positive potentials with added water.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Nitric acid (70%, redistilled, trace metal grade), acetic acid (99.9%), sodium acetate (> = 99%), deuterium oxide (D2O, 99.9%), RuCl3•3H2O, and 2,2′-bipyridine (> 99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. Syntheses of salts of complex 2 and its phosphonated analog 2-PO3H2 were reported elsewhere (36). Complex 1 and its phosphonated analog 1-PO3H2 were prepared by similar methods but with [Ru(tpy)]Cl3 as the precursor. All solutions were prepared with Milli-Q ultrapure water (> 18 MΩ).

FTO glass (Rs = 7–8 Ω) was obtained from Hartford Glass Company, Inc., and ITO glass (Rs = 4–8 Ω) was purchased from Delta Technologies. NanoITO powder (40-nm diameter) was obtained from Lihochem. Optically transparent, electrically conductive, high surface area nanoITO films were prepared as described previously (34, 35). The resulting films are light blue and approximately 2.5 µm in thickness with a resistance of Rs = ∼ 200 Ω across 1 cm of the film by a two-point probe measurement on a borosilicate glass substrate. TiO2 colloids (10- to 20-nm diameter) and semiconductive TiO2-coated FTO slides (10 μm in film thickness) were prepared according to literature procedures (37).

Instrumentation.

UV-visible spectra were recorded on an Agilent Technologies Model 8453 diode-array spectrophotometer. Electrochemical measurements were performed with the model CHI660D electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments). The three-electrode system consisted of a glass slide (area 1.25 cm2) working electrode, a Pt mesh counter electrode, and an SCE reference electrode (approximately 0.244 V vs. NHE at 22 °C and approximately 0.20 V vs. NHE at 80 °C). (Temperature coefficient (∂E/∂T) = -0.76 mV/K was applied for correction.)

Procedures.

Stable phosphonate surface binding of 2-PO3H2 on planar FTO to give FTO|2-PO3H2, on nanoITO films to give nanoITO|2-PO3H2 or on nanoTiO2 films to give nanoTiO2|2-PO3H2 occurred following immersion of the slides in solutions 0.2 mM in phosphonated complex at pH 5 (0.1 M  , HOAc/OAc-). The slides were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to remove physically adsorbed complex, followed by drying under a N2 gas stream. The extent of surface loading was varied by varying the soaking time with complete coverage after 2 h for FTO and 4 h for nanoITO and nanoTiO2. Table 1 lists saturated surface coverages, Γo in mole per square centimeter, for 2-PO3H2 derivatized FTO, nanoITO, and nanoTiO2. Surface binding by 1-PO3H2 utilized the same procedure.

, HOAc/OAc-). The slides were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to remove physically adsorbed complex, followed by drying under a N2 gas stream. The extent of surface loading was varied by varying the soaking time with complete coverage after 2 h for FTO and 4 h for nanoITO and nanoTiO2. Table 1 lists saturated surface coverages, Γo in mole per square centimeter, for 2-PO3H2 derivatized FTO, nanoITO, and nanoTiO2. Surface binding by 1-PO3H2 utilized the same procedure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Funding by Army Research Office through Grant W911NF-09-1-0426 (to Z.C.), the University of North Carolina Energy Frontier Research Center (EFRC) Solar Fuels and Next Generation Photovoltaics, an EFRC funded by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Award DE-SC0001011 (to J.J.C. and J.W.J.), and the Center for Catalytic Hydrocarbon Functionalization, an EFRC funded by the US Department of Energy under Award DE-SC0001298 at the University of Virginia (to A.K.V.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Author Summary on page 20863.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1115769108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Costentin C, Robert M, Savéant JM. Concerted proton-electron transfers: Electrochemical and related approaches. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:1019–1029. doi: 10.1021/ar9002812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huynh MHV, Meyer TJ. Proton-coupled electron transfer. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5004–5064. doi: 10.1021/cr0500030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammes-Schiffer S. Theory of proton-coupled electron transfer in energy conversion processes. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1881–1889. doi: 10.1021/ar9001284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren JJ, Tronic TA, Mayer JM. Thermochemistry of proton-coupled electron transfer reagents and its implications. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6961–7001. doi: 10.1021/cr100085k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petek H, Zhao J. Ultrafast interfacial proton-coupled electron transfer. Chem Rev. 2010;110:7082–7099. doi: 10.1021/cr1001595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binstead RA, Meyer TJ. Hydrogen-atom transfer between metal complex ions in solution. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:3287–3297. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costentin C, Robert M, Savéant JM, Teillout AL. Concerted proton-coupled electron transfers in aquo/hydroxo/oxo metal complexes: Electrochemistry of [OsII(bpy)2py(OH2)]2+ in water. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11829–11836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905020106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorp HH, Sarneski JE, Brudvig GW, Crabtree RH. Proton-coupled electron transfer in manganese complex [(bpy)2Mn(O)2Mn(bpy)2]3+ J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:9249–9250. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyon LA, Hupp JT. Energetics of the nanocrystalline titanium dioxide aqueous solution interface: Approximate conduction band edge variations between H0 = -10 and H- = +26. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:4623–4628. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabaniss GE, Diamantis AA, Murphy WR, Linton JRW, Meyer TJ. Electrocatalysis of proton-coupled electron-transfer reactions at glassy carbon electrodes. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:1845–1853. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trammell SA, et al. Mechanisms of surface electron transfer. Proton-coupled electron transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:13248–13249. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagliardi CJ, Jurss JW, Thorp HH, Meyer TJ. Surface activation of electrocatalysis at oxide electrodes. Concerted electron-proton transfer. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:2076–2078. doi: 10.1021/ic102524f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazaki S, Kojima T, Mayer JM, Fukuzumi S. Proton-coupled electron transfer of ruthenium(III)-pterin complexes: A mechanistic insight. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11615–11624. doi: 10.1021/ja904386r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alligrant TM, Alvarez JC. The role of intermolecular hydrogen bonding and proton transfer in proton-coupled electron transfer. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2011;115:10797–10805. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang WB, Rosendahl SM, Burgess IJ. Coupled electron/proton transfer studies of benzoquinone-modified monolayers. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2010;114:2738–2745. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reece SY, Nocera DG. Proton-coupled electron transfer in biology: Results from synergistic studies in natural and model systems. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:673–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.080207.092132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer TJ, Huynh MHV, Thorp HH. The possible role of proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) in water oxidation by photosystem II. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:5284–5304. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen ZF, Concepcion JJ, Jurss JW, Meyer TJ. Single-site, catalytic water oxidation on oxide surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15580–15581. doi: 10.1021/ja906391w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen ZF, et al. Concerted O atom-proton transfer in the O-O bond forming step in water oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7225–7229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001132107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Concepcion JJ, Jurss JW, Templeton JL, Meyer TJ. One site is enough. Catalytic water oxidation by [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(OH2)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(bpz)(OH2)]2+ J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16462–16463. doi: 10.1021/ja8059649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Concepcion JJ, et al. Making oxygen with ruthenium complexes. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1954–1965. doi: 10.1021/ar9001526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDaniel ND, Coughlin FJ, Tinker LL, Bernhard S. Cyclometalated iridium(III) aquo complexes: Efficient and tunable catalysts for the homogeneous oxidation of water. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:210–217. doi: 10.1021/ja074478f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hull JF, et al. Highly active and robust Cp* iridium complexes for catalytic water oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8730–8731. doi: 10.1021/ja901270f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wasylenko DJ, et al. Electronic modification of the [RuII(tpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ scaffold: Effects on catalytic water oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:16094–16106. doi: 10.1021/ja106108y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul A, et al. Multiple pathways for benzyl alcohol oxidation by RuV = O3+ and RuIV = O2+ Inorg Chem. 2011;50:1167–1169. doi: 10.1021/ic1024923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson MS, Meyer TJ. Mechanisms of oxidation of 2-propanol by polypyridyl complexes of ruthenium(III) and ruthenium(IV) J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4106–4115. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. 2nd Ed. New York: Wiley; 2001. pp. 580–631. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trammell SA, Meyer TJ. Diffusional mediation of surface electron transfer on TiO2. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bratsch SG. Standard electrode potentials and temperature coefficients in water at 298.15 K. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 1989;18:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auer B, Fernandez LE, Hammes-Schiffer S. Theoretical analysis of proton relays in electrochemical proton-coupled electron transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8282–8292. doi: 10.1021/ja201560v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen ZF, et al. Nonaqueous catalytic water oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17670–17673. doi: 10.1021/ja107347n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brennaman MK, et al. Interfacial electron transfer dynamics following laser flash photolysis of [Ru(bpy)2((4,4′-PO3H2)2bpy)]2+ in TiO2 nanoparticle films in aqueous environments. ChemSusChem. 2011;4:216–227. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muzikar J, van de Goor T, Gaš B, Kenndler E. Propylene carbonate as a nonaqueous solvent for capillary electrophoresis: Mobility and ionization constant of aliphatic amines. Anal Chem. 2002;74:428–433. doi: 10.1021/ac010887x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoertz PG, Chen ZF, Kent CA, Meyer TJ. Application of high surface area tin-doped indium oxide nanoparticle films as transparent conducting electrodes. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:8179–8181. doi: 10.1021/ic100719r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen ZF, Concepcion JJ, Hull JF, Hoertz PG, Meyer TJ. Catalytic water oxidation on derivatized nanoITO. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:6950–6952. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00362j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Concepcion JJ, et al. Catalytic water oxidation by single-site ruthenium catalysts. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:1277–1279. doi: 10.1021/ic901437e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heimer TA, D’Arcangelis ST, Farzad F, Stipkala JM, Meyer GJ. An acetylacetonate-based semiconductor-sensitizer linkage. Inorg Chem. 1996;35:5319–5324. [Google Scholar]