Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

The main objective of this study was to investigate the risk factors associated with periodontitis in pregnant women.

METHODS:

This study was conducted in two stages. In Stage 1, a cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the prevalence of periodontitis among 810 women treated at the maternity ward of a university hospital. In Stage 2, the factors associated with periodontitis were investigated in two groups of pregnant women: 90 with periodontitis and 720 without. A hierarchized approach to the evaluation of the risk factors was used in the analysis, and the independent variables related to periodontitis were grouped into two levels: 1) socio-demographic variables; 2a) variables related to nutritional status, smoking, and number of pregnancies; and 2b) variables related to oral hygiene. Periodontitis was defined as a probing depth ≥4 mm and an attachment loss ≥3 mm at the same site in four or more teeth. A logistic regression analysis was also performed.

RESULTS:

The prevalence of periodontitis in this sample was 11%. The variables that remained in the final multivariate model with the hierarchized approach were schooling, family income, smoking, body mass index, and bacterial plaque.

CONCLUSION:

The factors identified underscore the social nature of the disease, as periodontitis was associated with socioeconomic, demographic status, and poor oral hygiene.

Keywords: Risk Factors, Periodontitis, Periodontal Disease, Pregnancy, Gingivitis

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease is caused by a complex set of conditions affecting the tissues that protect and support the teeth. There are several stages as well as different onset and progression patterns associated with this condition, and bacterial plaque and host susceptibility are responsible for a large portion of the clinical variations (1-3). The main alterations caused by periodontitis are alveolar bone reabsorption and the disappearance of the fibers connecting the bone to the tooth (periodontal ligament), which lead to loss of attachment and the consequent formation of a periodontal pocket that serves as a reservoir for pathogenic oral microorganisms (4).

A number of factors are involved in the occurrence of periodontitis. The non-modifiable aspects of disease development include genetic factors, age, ethnicity, gender, and systemic diseases, especially diabetes and AIDS. The modifiable aspects include socioeconomic status, smoking, oral hygiene, obesity, stress (5-6), and specific hormonal alterations during pregnancy (7-9). A number of alterations in the oral cavity may become more prevalent during pregnancy, and pregnancy gingivitis is characterized by hyperemia, edema, and a considerable tendency for bleeding. This type of gingivitis occurs at a frequency ranging from 35 to 100%, and the severity gradually increases until the 36th week of gestation (8-10).

A number of studies have demonstrated variability in the frequency of periodontitis among pregnant women (7,8,10). Although triggered by a buildup of bacterial plaque, periodontitis can be exacerbated by vascular and hormonal changes. Taken alone, these changes do not determine the course of the infectious processes, but they aggravate the response of the tissues to the presence of bacterial plaque. This condition is produced in conjunction with an increase in the percentage of anaerobic bacteria, especially Prevotella intermedia, which is caused by the increase in the serum levels of circulating estrogen and progesterone. By the end of pregnancy, progesterone levels have increased ten-fold and estrogen levels have increased 20-fold over those observed during the menstrual cycle (7,8). A number of studies support an association between chronic periodontitis and premature birth. The periodontal pockets serve as a chronic reservoir for the translocation of bacteria (mostly Gram-negative bacteria, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia) and their virulent products, which reach the fetal-placental unit through the hematogenic pathway and can trigger premature labor (2-4,9,11-14).

The investigation of risk factors for periodontitis involves the collection of data regarding a considerable number of variables. Hierarchized modeling enables the establishment of levels for variable entry. The adjustment for each level, based on the construction of the conceptual model by Victora et al. (15), encompasses biological and statistical aspects, thereby allowing an investigation of better structured results. No studies in the literature have employed this strategy for the analysis of periodontitis-disposing factors in pregnant women. The identification of risk factors for periodontitis during pregnancy can help guide and establish early treatment, which can lead to the avoidance of the possible adverse effects of this disease on pregnancy.

Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate periodontitis-associated risk factors among pregnant women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a mixed-method study incorporating cross-sectional and case-control designs with hierarchical models. The study aimed to determine the prevalence of periodontitis among pregnant women and study the periodontitis-associated risk factors. Women who were treated at the maternity ward of a university hospital [Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE)] in the city of Recife (northeastern Brazil) between November 2007 and August 2008 were selected for the study. The maternity ward in question is a reference unit for high-risk pregnancies. All pregnant women who gave birth in this maternity ward throughout the duration of the data collection period were considered eligible for the study, regardless of age group or gestational age, provided that a live birth was achieved.

Women who required antibiotic prophylaxis in order to undergo the periodontal exam and those with systemic disease (chronic diabetes, heart disease, systemic lupus, nephropathy, and hypertension prior to pregnancy) were excluded from the study. The exclusion criteria data were obtained through clinical histories, the results of serological exams that had been recorded on prenatal charts, and the medical charts from the maternity ward.

Calculation of sample size

The calculation of the sample size was based on the study that was conducted by Al-Zahrani et al. (16), which found a 14% prevalence of periodontitis, assuming a 3% error with a 95% level of confidence. We used the Statcalc tool of the Epi-Info program, version 6.04d (Center of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA), to determine the minimal necessary sample size of 415 patients.

To calculate the sample size, with the aim of investigating the factors associated with periodontitis and with the assumption that smoking was the main exposure factor, we used methods proposed by Al-Zahrani et al. (16). This study reported a 23.7% frequency of smoking among individuals without periodontitis and a frequency of 40.1% among those with periodontitis, which corresponded to an odds ratio of 2.16. With a 5% α error, 20% β error, and 80% power, the minimal sample size necessary was found to be 83 patients with periodontitis and 332 without the disease.

For the cross-sectional study, no additional percentage was calculated to compensate for possible losses, as the decision was made to extend the collection period until the estimated sample size was reached. As the second stage of the study (case-control study) required a minimum of 83 cases, the decision was made to continue recruitment until this number of cases was collected. In the final sample, 810 women had been selected, including 90 cases and 720 controls. The increase in the number of controls per cases enhanced the statistical power of the study.

Data collection

Within 48 hours after giving birth, the women who did not fulfill any of the exclusion criteria were recruited at the maternity ward by a neonatologist (a member of the research team). Those who matched the selection criteria received an explanation regarding the study and were asked to participate. Those who accepted signed terms of informed consent and answered a pre-coded questionnaire addressing socioeconomic and demographic variables, current and past gestational history, information on prenatal care, complications during pregnancy, smoking, and aspects related to oral health. None of the women refused to participate. A pre-coded, semi-structured questionnaire was administered to the women by one of the researchers for the collection of maternal variables. Information on prenatal care was also obtained from the prenatal chart, and information regarding complications during pregnancy and co-morbidities was also obtained from the patient medical charts.

Oral clinical exam

The periodontal exam was performed by a single dentist who had been trained by a periodontist from the Department of General and Preventive Dentistry (UFPE). The exam was performed during morning hours with the patient in the maternity bed, and the exam occurred within 48 hours after giving birth and prior to discharge. For the exam, a flat n° 5 mirror and periodontal probe from the University of North Carolina (USA) (Hu-Friedy, reference PCPUNC15BR) were used. The probing depth (distance between the gingival border and base of the gingival sulcus) and gingival recession (distance between the enamel-cementum junction and border of marginal gingival tissue) were determined at six points (three on the vestibular face and three on the lingual or palatal face) on all teeth except the third molars. Clinical attachment loss was determined by summing the probing depth and the gingival recession. Dental plaque was quantified using the visible plaque index (17).

Definition of variables

Dependent variable: chronic periodontitis

Chronic periodontitis was defined when there were four or more teeth that had one or more sites with a probing depth ≥4 mm and a clinical attachment loss ≥3 mm at the same site. These criteria were based on those described in a study by Lopez et al. in 2002 (11), which suggested that the combination of these two variables provided a more rigorous, and therefore specific, measurement of the disease and a consequent reduction in the likelihood of false-positive results. Only moderate and severe cases of chronic periodontitis were included in this study.

Independent variables (covariables)

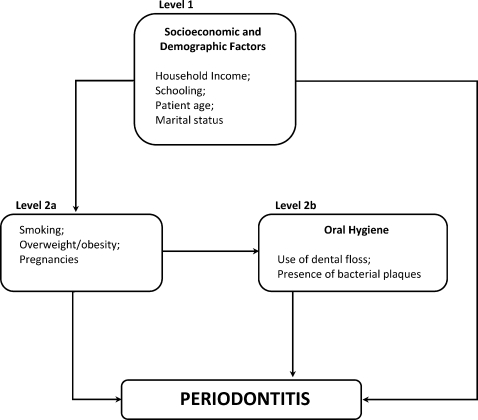

The independent variables were hierarchically grouped on the following two levels: 1) socio-demographic variables; 2a) variables related to nutritional status, smoking and number of pregnancies; and 2b) variables related to oral hygiene. The conceptual, theoretical model designed by the authors was used as the basis for this grouping (Figure 1).

Hierarchized model of risk factors for periodontitis in pregnant women, Recife, Brazil, 2008.

Level 1

Schooling, household income, age, marital status

Level 2a

Body mass index (BMI), based on the criteria proposed by Al-Zahrani et al. in 2003 (16); smoking before and during pregnancy; duration of smoking habit; previous births

Level 2b

Oral hygiene status

The data collected from the first 100 patients were used as the pilot study to evaluate the questionnaire.

Data processing and analysis

The questionnaires regarding the clinical and periodontal information were entered twice into a file previously prepared for the insertion of data and were analyzed using Epi-info version 6.04, followed by Stata version 9.0 (StataCorp, Texas, USA). The univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using non-conditional logistic regression. The entire sample was first divided into the following two groups: women with periodontitis and those without the disease. The analysis was performed using a hierarchical approach considering the two different levels. For each level, a univariate analysis was performed to investigate the association between each independent variable and periodontitis. The odds ratios (ORs) were estimated, the 95% confidence intervals were constructed and the p-values were determined. A multivariate analysis was then performed for each level using a stepwise multiple logistic regression. Variables with p-values <0.20 in the univariate analysis were introduced to the multivariate model on each level, whereas those with p-values <0.10 after adjustment on the same level and on previous levels remained in the model.

The proposed model assumes that hierarchically superior risk factors exert their action through variables situated below (Figure 1). The variables in the conceptual model related to oral hygiene and those related to nutritional status, smoking, and previous pregnancies are displayed side by side. However, for the adjustment, these variables were analyzed on different levels, such that variables at Level 2b were not directly influenced by those at Level 2a. Thus, even variables for which the association was no longer significant following the adjustments remained in the model.

Ethical aspects

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Center for Health Sciences of the Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (Brazil) under process n° CAAE 0268.0.172.000-07. As a benefit of their participation, the women were sent for treatment at a specialized UFPE periodontal clinic following their periodontal status diagnosis.

RESULTS

The prevalence of periodontitis in the sample was 11% (95% CI: 9.1 to 13.4), which corresponded to 90 women with periodontitis and 720 without the disease. Four women had severe periodontitis. Table 1 displays the general characteristics of the participants with and without periodontitis.

Table 1.

General characteristics of participants with and without periodontitis from Recife, Brazil, 2008.

| Variables | Periodontitis | Total | p(X2) | ||||

| Yes | No | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Age | |||||||

| 13-19 | 17 | 18.9 | 232 | 32.2 | 249 | 30.74 | 0.030 |

| 20-29 | 50 | 55.6 | 347 | 48.2 | 397 | 49.01 | |

| 30-46 | 23 | 25.6 | 141 | 19.6 | 164 | 20.24 | |

| Schooling (years) | |||||||

| 0-4 | 65 | 72.2 | 157 | 21.8 | 222 | 27.40 | 0.000 |

| 5-8 | 20 | 22.2 | 362 | 50.3 | 382 | 47.16 | |

| 9 or more | 5 | 5.6 | 201 | 27.9 | 206 | 25.43 | |

| Income | |||||||

| <1 minimum salary (MS)** | 80 | 88.9 | 423 | 58.8 | 503 | 62.09 | 0.000 |

| ≥1 MS | 10 | 11.1 | 297 | 41.3 | 307 | 37.90 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single | 56 | 62.2 | 209 | 29.0 | 265 | 32.71 | 0.000 |

| Stable partner | 34 | 37.8 | 511 | 71.0 | 545 | 67.28 | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | |||||||

| <19 | 9 | 10.0 | 119 | 16.5 | 128 | 15.80 | 0.000 |

| 19-25 | 31 | 34.4 | 446 | 61.9 | 477 | 58.88 | |

| 26 or more | 50 | 55.6 | 155 | 21.5 | 205 | 25.30 | |

| Smoking | |||||||

| *)Yes | 54 | 60.0 | 87 | 12.1 | 141 | 17.40 | 0.000 |

| <5 years | 41 | 45.5 | 27 | 3.8 | 68 | 8.39 | |

| >5 years | 13 | 14.5 | 58 | 8.1 | 71 | 8.76 | |

| No | 36 | 40.0 | 633 | 88.1 | 669 | 82.59 | |

| Bacterial plaque | |||||||

| Yes | 88 | 97.8 | 557 | 77.4 | 645 | 79.62 | 0.000 |

| No | 2 | 2.2 | 163 | 22.6 | 165 | 20.37 | |

| Dental floss usage | |||||||

| No | 82 | 91.1 | 558 | 77.5 | 640 | 79.01 | |

| Yes | 8 | 8.9 | 162 | 22.5 | 170 | 20.98 | 0.004 |

Two smokers in group without periodontitis did not offer information on smoking habit duration.

1 minimum salary (MS) is equivalent to US$ 250.00.

Socioeconomic and demographic variables (Level 1)

In the univariate analysis, women with less schooling (up to four years), single women, those with a low income (≤1 minimum salary, equivalent to US$ 250.00) and those over 30 years of age had a greater chance of exhibiting periodontitis. Schooling, household income, and marital status remained in the model at the same level as socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. These variables remained associated with periodontitis even after they were adjusted to the other variables on this level and were therefore used for the analyses on the subsequent levels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of the association between the socioeconomic-demographic variables and periodontitis in pregnant women from Recife, Brazil, 2008.

| Variables | OR a) | (95% CI)a) | Non-adjustedp-value | OR b) | (95% CI) b) | p-value adjusted for intra-level variables |

| Schooling (years) | ||||||

| 9 or more | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 5-8 | 2.22 | (0.77-6.86) | 0.16 | 1.76 | (0.63-4.87) | 0.270 |

| 0-4 | 16.64 | (6.25-48.12) | 0.0001 | 8.79 | (3.33-23.20) | 0.000 |

| Income | ||||||

| >1 MS | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ≤1 MS | 5.62 | (2.75-11.81) | 0.0001 | 3.18 | (1.56-6.50) | 0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Stable partner | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Single | 4.03 | (2.48-6.54) | 0.0001 | 2.27 | (1.38-3.74) | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 13-19 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 20-29 | 1.97 | (1.07-3.64) | 0.027 | 1.76 | (0.94-3.28) | 0.070 |

| 30 or more | 2.23 | (1.10-4.53) | 0.024 | 1.65 | (0.80-3.41) | 0.170 |

non-adjusted.

adjusted for schooling, household income, marital status and patient age.

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

MS: minimum salary; 1 MS equivalent to US$ 250.00.

Variables related to smoking, overweight/obesity and previous pregnancies (Level 2a)

Table 3 displays the variables related to smoking, BMI, and previous pregnancies. A total of 17.4% (141/810) of the women reported being smokers, and 51% of these women had continued the habit for more than five years. The shortest duration of smoking reported was one year. Smoking status, an overweight/obese state, and multiple pregnancies exhibited statistically significant associations with periodontitis in a univariate analysis. These variables were introduced into the multivariate model by the lowest p-value, and smoking and obesity were then identified as more closely associated with periodontitis.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the association between smoking, body mass index, pregnancies, and periodontitis in pregnant women from Recife, Brazil, 2008.

| Variables | OR a) | (95% CI) a) | pa) | OR b) | (95% CI) b) | pb) | OR c) | (95% CI) c) | pc) |

| Smoking before and during pregnancy | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 10.91 | (6.56-18.19) | 0.000 | 7.97 | (4.83-13.14) | 0.000 | 3.79 | (2.14-6.74) | 0.000 |

| BMI | |||||||||

| Underweight/normal | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Overweight/obesity | 4.64 | (2.79-7.75) | 0.000 | 2.77 | (1.68-4.57) | 0.000 | 2.22 | (1.28-3.83) | 0.004 |

| Number of pregnancies | |||||||||

| One | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Multiple | 2.38 | (1.42-4.02) | 0.000 | 1.49 | (0.87-2.56) | 0.14 | - | - | |

non-adjusted.

adjusted for intra-level variables (smoking, obesity, pregnancies).

adjusted for intra-level variables and hierarchically superior variables (schooling, household income, marital status).

OR: Odds Ratio; CI: confidence interval; p: p-value.

BMI: body mass index.

Variables related to oral health (bacterial plaque and use of dental floss) (Level 2b)

The presence of bacterial plaque and the non-use of dental floss were significantly associated with periodontitis in a univariate analysis. In the multivariate model, after the intra-level adjustment and the adjustment for the hierarchically superior variables were made, only bacterial plaque remained associated with periodontitis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of the association between oral health variables and periodontitis in pregnant women from Recife, Brazil, 2008.

| Variables | OR a) | (95% CI) a) | pa) | OR b) | (95% CI) b) | pb) | OR c) | (95% CI) c) | pc) |

| Bacterial plaque | |||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 12.88 | (3.05 - 77.40) | 0.0001 | 12.33 | (3.00 - 50.72) | 0.000 | 14.07 | (3.26 - 60.79) | 0.000 |

| Use of dental floss | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| No | 2.98 | (1.35 - 6.84) | 0.004 | 2.78 | (1.31 - 5.90) | 0.008 | 1.17 | (0.50 - 2.75) | 0.717 |

non-adjusted.

adjusted for intra-level variables (bacterial plaque, use of dental floss).

adjusted for intra-level variables and hierarchically superior variables (schooling, household income, marital status, smoking, obesity).

OR: Odds Ratio; CI: confidence interval; p: p-value.

Table 5 displays the final hierarchized model presenting the factors of different levels that remained associated with periodontitis, including less than four years of schooling, household income ≤1 minimum salary (equivalent to US$ 250.00), non-cohabitation with the father of the child, smoking, an overweight/obese state, and bacterial plaque.

Table 5.

Final multivariate model of periodontitis-associated risk factors in pregnant women from Recife, Brazil, 2008.

| Variables | ORa | (95% CI) a | p-value adjusted for all variables |

| Level 1 | |||

| Schooling (years) | |||

| 9 or more | 1.00 | ||

| 5-8 | 1.38 | (0.49 - 3.90) | 0.530 |

| 0-4 | 4.54 | (1.62 - 12.75) | 0.004 |

| Household Income | |||

| >1 MS | 1.00 | ||

| ≤1 MS | 2.34 | (1.11 - 4.94) | 0.025 |

| Marital status | |||

| Stable partner | 1.00 | ||

| Single | 1.58 | (0.90 - 2.76) | 0.110 |

| Level 2a | |||

| Smoking beforeand during pregnancy | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 4.17 | (2.31 - 7.50) | 0.000 |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight/normal | 1.00 | ||

| Overweight/obesity | 2.28 | (1.29 - 4.02) | 0.004 |

| Level 2b | |||

| Bacterial plaque | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 14.04 | (3.25 - 60.64) | 0.000 |

(a) Adjusted for all variables selected in the model.

DISCUSSION

The present investigation is one of the first studies to address periodontal risk factors for pregnant women. Specifically, this study evaluated women treated at a maternity ward for high-risk pregnancies at a university hospital in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil using a hierarchal model. The hierarchized analysis identified the following as periodontal risk factors in this population: a lower degree of schooling, low income, single marital status, obesity prior to pregnancy, multiple births, smoking, and poor oral hygiene (based on presence of visible bacterial plaque).

In the hierarchized model, a variable from a particular level that exhibited a statistically significant association, following adjustments for the other variables on the same level, would remain in the model even if this association was no longer considered statistically significant following adjustment for variables on the most proximal level, as proximal variables mediate the effects of more distal variables (15).

The observation that patients with a lower degree of schooling and lower income had a greater chance of exhibiting periodontitis is in agreement with findings described by previous studies, which have documented a close association between periodontitis and socioeconomic status (5,6). Schooling exerted a greater influence than income on the likelihood of periodontitis. These findings are also consistent with those reported in previous observational studies, which have documented differences in periodontal health regarding socio-demographic indicators such as income and schooling (18,19). Studies have found a higher prevalence and greater severity of periodontitis among patients with a lower socioeconomic status (1,19), which likely stems from differences in access to resources and opportunities that may influence preventive behavior. Therefore, a low economic status and less access to general care and dental health care may lead to a poorer periodontal status.

In the multivariate model, patient age lost statistical significance after the adjustments for the other variables on the same level were performed. Previous evidence has demonstrated that both the prevalence and severity of periodontitis increase with age, suggesting that age may be an indicator of the loss of periodontal support tissue (1,19). Thus, it is conceivable that age has a prolonged, cumulative effect on other risk factors. In the present study, the sample consisted mostly of young women (mean age of 30 years), which may have led to the finding that age did not remain associated with periodontitis in the final multivariate model.

The univariate analysis revealed that single women (those who did not cohabitate with the father of the child) had a greater likelihood of exhibiting periodontitis than those in a stable relationship. However, the adjustment for confounding factors substantially reduced the statistical power of the risk represented by marital status, and the study by Vogt (3) described a similar finding.

Smoking prior to and during pregnancy was strongly associated with periodontitis. It is likely that smokers have a reduced capacity for an inflammatory response to microbial changes. Cross-sectional and case-control studies conducted on adult smokers have demonstrated an estimated risk of the association between smoking and periodontal disease to range from 1.4 to 11.8 (20,21). These studies reported greater colonization by periodontal pathogens in the bacterial plaque of smokers. In the present study, the positive association between smoking and periodontitis is similar to that reported in a number of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that have investigated the effect of smoking on periodontal status, either as the main exposure factor of interest or as a covariable (1,20-23).

Women who are overweight or obese had a greater likelihood of exhibiting periodontitis in the present study. The underlying biological mechanism of the association between obesity and periodontitis in pregnant women remains poorly understood. However, recent studies involving adult subjects have demonstrated that obesity is a potential risk factor for periodontal disease (24-26). Adipose tissue produces a large amount of inflammatory cytokines and hormones, collectively called adipokines or adipocytokines, which may affect periodontitis. Thus, it is likely that the increase in body fat raises the probability of an active inflammatory response to periodontal disease (24-26). Researchers in Jordan found that adult women with a BMI>30 Kg/m2 had a three-fold greater probability of exhibiting periodontitis compared to those within the normal weight range (24).

Higher bacterial plaque index values were found in the periodontitis patient group, supporting that notion that plaque is the primary etiological factor for the disease, although the quality and virulence of the plaque are known to be more important than plaque quantity. The finding that bacterial plaque was a risk factor for periodontitis in the present investigation is in agreement with the findings described in previous studies (3,7,10).

There is a certain degree of diversity among the results of different studies with regard to the measurement of periodontitis. This may be explained by differences in sample size as well as the ethnicity and socioeconomic status of the population studied. There is no consensus in the literature as to the definition of the disease, which would be an essential component for the optimization of the interpretation and the comparison and validation of clinical findings (27). A number of studies have used the Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (28-29). to measure disease, whereas others have used the measurement of bleeding upon probing (30,31). Additionally, many studies use periodontal pocket depth or clinical attachment loss (22,26) as a definition. In the present study, periodontitis was defined based on the criteria proposed by Lopez et al. (11), which are considered more rigorous and, therefore, more specific for measuring the disease and consequently reducing the likelihood of obtaining false-positive results (5).

The cross-sectional design of the present study limited its ability to establish a temporal sequence or focus on incident case. While we cannot discount the potential for classification errors regarding certain variables (BMI, smoking, use of dental floss), such errors would not have had a significant effect on the results, as the researcher was unaware of the results of the oral exam and the dentist had no access to the contents of the interviews. The potential for classification errors regarding the outcome was minimized by the specificity of the criteria used for the diagnosis of periodontitis with Lopez's criteria (11). Moreover, the likelihood of a selection bias was minimized by the case-control strategy. Due to the fact that the institution where the study was conducted is a reference service for high-risk pregnancies, the prevalence of periodontitis found in these patients may differ from that of other groups of pregnant women.

The risk factors associated with periodontitis during pregnancy in the present study included a low degree of schooling, low income, smoking, the presence of visible plaque, and obesity prior to pregnancy. These factors have also been cited in the literature as risk factors in other population groups. Despite their association, studies have demonstrated that pregnancy does not cause periodontitis but rather may exacerbate preexisting periodontal conditions (8). A number of studies have recently indicated that periodontitis is likely a risk factor for preeclampsia, premature birth and low birth weight. Therefore, oral health measures directed at pregnant women are of considerable importance (8). It is necessary to sensitize healthcare professionals (especially obstetricians, who are often the only health professional in contact with the patient) to the importance of referring pregnant women to a dentist for evaluation, orientation and treatment, if necessary.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albandar JM. Global risk factors and risk indicators for periodontal diseases. Periodontology. 2000. 2002;29:177–206. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290109.x. 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mascarenhas P, Gapski R, Al-Shammari K, Wang HL. Influence of sex hormones on the periodontium. Journal Clinical Periodontology. 2003;30:671–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00055.x. 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2003.00055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogt M. Periodontite e resultados perinatais adversos em uma coorte de gestantes. Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Odontologia de Piracicaba, da Universidade Estadual de Campinas, para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Clínica Odontológica. Área de Periodontia. Piracicaba. 2006:216p. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffcoat MK, Hauth JC, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Hodg Kins PM. Periodontal disease and preterm birth: results of pilot intervention study. Journal of Periodontolology. 2003;74:1214–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1214. 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borrell LN, Papapanou PN. Analytical epidemiology of periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2005;32:132–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00799.x. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00799.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day'S Charlotte N. The global burden of diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:661–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontologica Scandanavica. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laine MA. Effect of pregnancy on periodontal and dental health. Acta Odontologica Scandanavica. 2002;60:257–64. doi: 10.1080/00016350260248210. 10.1080/00016350260248210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taani DQ, Habashneh R, Hammad MM, Batieha A. The periodontal status of pregnant women and its relationship with socio-demographic and clinical variables. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2003;30:440–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01058.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss KL, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. Clinical Risk factors associated with incidence and progression of periodontal conditions in pregnant women. Journal Clinical Periodontology. 2005;32:492–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00703.x. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez NJ, Smith PC, Gutierrez J. Higher risk of preterm birth and low birth weight in women with periodontal disease. Journal of Dental Research. 2002a;81:58–63. doi: 10.1177/002203450208100113. 10.1177/154405910208100113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieff S, Bogges KA, Murtha AP, Jared H, Madianos PN, Moss K. The oral conditions and pregnancy study: periodontal status of cohort of pregnant women. Journal of Periodontology. 2004;75:116–26. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.1.116. 10.1902/jop.2004.75.1.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jae-In R, Oh KJ, Yang H, Choi BK, Ha JE, Jin BH. Health Behaviors, Periodontal conditions, and periodontal pathogens in spontaneous preterm birth: a case-control study in Korea. Journal of Periodontolology. 2010;81:855–63. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090667. 10.1902/jop.2010.090667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nabet C, Lelong N, Colombier ML, Sixou M, Musset AM, Goffinet F. Maternal periodontitis and the causes of preterm birth: the case –controle Epipap study. Journal Clinical Periodontology. 2010;37:37–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01503.x. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01503.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MTA. The Role of Conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: A hierarchical approach. International Journal of Epidemioogyl. 1997;26:224–27. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.224. 10.1093/ije/26.1.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Zahrani MS, Bissada NF, Borawskit EA. Obesity and periodontal disease in young, middle-aged, and older adults. Journal of Periodontology. 2003;74:610–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.5.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. International Dental Journal. 1975;25:229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borrell LN, Burt BA, Gillespie BW, Lynch J, Neighbors H. Race and periodontitis in the United States: beyond black and white. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 2002a;62:92–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2002.tb03428.x. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2002.tb03428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borrell LN, Burt BA, Neighbors HW, Taylor GW. Social factors and periodontitis in an older population. American Public Health Association. 2004;94:748–54. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.748. 10.2105/AJPH.94.5.748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Winkelhoff AJ, Bosch-Tijhof CJ, Winkel EG, Van der Reijen W. Smoking affects the subgingival microflora in periodontitis. Journal Periodontology. 2001;72:666–71. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.5.666. 10.1902/jop.2001.72.5.666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomes SC, Piccinin FB, Oppermann RV. Periodontal status in smokers and never- smokers:clinical findings and real- time polymerase chain reaction quantification of putative periodontal pathogens. Journal of Periodontolology. 2006;77:1483–90. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060026. 10.1902/jop.2006.060026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogawa H, Yoshihara A, Hirotomi T. Risk factors for periodontal disease progression. Journal Clinical Periodontology. 2002;29:592–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290702.x. 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2002.290702.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Velden U, Varoufaki A, Hutter JW, Xu L, Timmerman MF, Van Winkelhoff AJ. Effect of smoking and periodontal treatment on the subgingival microflora. Journal Clinical Periodontology. 2003;30:603–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00080.x. 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2003.00080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishimura F, Murayama Y. Periodontal inflammation and insulin resistance –lessons from obesity. Journal of Dental Research. 2001;80:1690–4. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800080201. 10.1177/00220345010800080201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood N, Johnson RB, Streckfus CF. Comparison of body composition and periodontal disease using nutritional assessment techniques: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Journal Clinical Periodontoogyl. 2003;30:321–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00353.x. 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2003.00353.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapper A, Munch A, Shermann C. Obesity and periodontal disease in diabetic pregnant women. Brasilian Oral Research. 2005;19:83–7. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242005000200002. 10.1590/S1806-83242005000200002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vettore MV, Lamarca GA, Leão ATT, Thomas FB, Sheiham A, Leal MC. Periodontal infection and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Cadernos de Saude Pública. 2006;22:2041–53. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006001000010. 10.1590/S0102-311X2006001000010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davenport ES, Williams CE, Stern JA. Maternal periodontal disease and preterm low birthweight: case control study. Journal of Dental Research. 2002;81:313–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100505. 10.1177/154405910208100505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noack B, Klingenberg J, Weigelt J, Hoffmann T. Periodontal status and preterm low birth weight: a case control study. Journal of Periodontal Research. 2005;40:339–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2005.00808.x. 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2005.00808.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore S, Randhaw M, Ide M. A case-control study to investigate an association between adverse pregnancy outcome and periodontal disease. Journal Clinical Periodontology. 2005;32:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00598.x. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogges KA, Beck JD, Murtha AP, Moss K, Offenbacher S. Maternal periodontal disease in early pregnancy and risk for a small-for-gestacional-age infant. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;194:1316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.059. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]