Abstract

Community engagement is an on-going, arduous, and necessary process for developing effective health promotion programs. The challenges are amplified when the particular health issue or research question is not prominent in the consciousness of the targeted community. In this paper, we explore the community-based participatory research (CBPR) model as a means to negotiate a mutual agenda between communities and researchers.

The paper is focused on the (perceived) need for cervical cancer screening in an under-resourced community in Cape Town, South Africa. Cervical cancer is a significant health problem in this community and elsewhere in South Africa. Unlike HIV-AIDS, however, many Black South Africans have not been educated about cervical cancer and the importance of obtaining screening. Many may not consider screening a priority in their lives.

Our research included extensive consultations and informal interviews with diverse community and regional stakeholders. Following these, we conducted 27 focus groups and 106 demographic surveys with randomly selected youth, parents, local health care personnel, educators and school staff. Focus group data were summarized and analyzed cross-sectionally. Community stakeholders were involved throughout this research.

Our consultations, interviews, and focus group data were key in identifying the concerns and priorities of the community. By engaging community stakeholders, we developed a research framework that incorporated the community’s concerns and priorities, and stressed the intersecting roles of poverty, violence, and other cultural forces in shaping community members’ health and wellbeing. Community members helped to refocus our research from cervical cancer to ‘cervical health,’ a concept that acknowledged the impact on women’s bodies and lives of HIV-AIDS and STDs, sexual violence, poverty, and multiple social problems. We conclude that the research agenda and questions in community-based health research should not be considered immutable. They need to be open to negotiation, creativity, and constant reinvention.

Keywords: South Africa, Community-based participatory research, Cervical cancer, Community engagement

Introduction

The development of a research question is a critical process in any research project (Elden, 1987). It is particularly critical in community-based research, where questions formulated without the input and involvement of community stakeholders can undermine the research and its chances of success from the outset. In this paper, we examine how the community-based participatory research (CBPR) model can be used to develop, refine, and give momentum to health education and promotion efforts in their early phases. We illustrate how, through informal interviews, focus groups, and a series of field visits, we shifted our narrow interest in the risk factors for cervical cancer to a broader emphasis on “cervical health” that is grounded in the larger context of community health and wellbeing.

By engaging community stakeholders, we developed a research framework that incorporated the community’s concerns and priorities, and stressed the intersecting roles of poverty, violence, and other cultural forces in shaping community members’ health and wellbeing. In reframing our research interest as “cervical health,” we acknowledged that women’s health in South Africa extends well beyond epidemiological factors, and includes HIV-AIDS and STDs, sexual violence, poverty, and multiple other social problems. This paper discusses how the CBPR model can help ground a study in local interest and support, forge key partnerships, and promote mutual credibility and trust. The paper concludes with a number of recommendations to community health researchers and educators seeking to adopt the CBPR approach, particularly in low-resource, “democracy conscious” communities.

CBPR: Recognizing the context

CBPR may be viewed as part of the continuing drive in social research to transcend academic boundaries and shift toward interdisciplinary collaborations (Stoecker & Bonancich, 1993). Beyond knowledge production, CBPR seeks action and change as its primary goals, simultaneously functioning as both research and service (Petras & Porpora, 1993). CBPR is described as using the social sciences to advance the “democratic process” (Bailey, 1992). In public health, community-based participatory methods derive from a renewed focus on the social, political, and economic behaviors that impinge on health behavior and influence access to local resources (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). CBPR is an effective way to understand urban health issues ecologically, through consideration of the social and environmental contexts in which these issues are embedded (Higgins & Metzler, 2001). However, the CBPR approach may not be applicable in all research environments and the continuation of independent, scholarly research methodologies to evaluate health issues remains essential.

One of the greatest challenges of early stage CBPR lies in establishing trust in communities that are inherently suspicious of university or other “outside” involvement. As Reardon and colleagues have pointed out, communities may sense that academics use other people’s distress to justify grant money, which produces money for faculty but has little lasting impact on the community (Reardon, Welsh, Kreiswirth, & Forrester, 1993). This is a prominent issue in South Africa. As Nama and Swartz (2002) have pointed out, local communities in South Africa are “very much aware of the fact that in the past researchers (who were mainly White) would collect data on impoverished people without making any contribution to improvement of their lives. (p. 289)” South African academics in the past frequently approached poor communities, and the idea of “community” itself, as a testing ground for dubious academic claims about race, culture, and social cohesion (Thornton & Ramphele, 1988). Since the late 1980s in particular, communities in South Africa have been very vigilant about this form of exploitation (Nama & Swartz, 2002). Increasingly, researchers in South Africa and other parts of the developing world can gain access to communities only after consulting with local stake-holders, who will want assurances that the research is ethically sound and respectful of local concerns and norms, not exploitive, and committed at some level to the wellbeing of the community (Marshall & Rotimi, 2001; Quinn, 2004).

CBPR in South Africa: A logical approach

Given South Africa’s sociopolitical environment, CBPR seems an almost natural and obvious fit. Owing to the country’s recent political history, many South African communities embody the CBPR principles of collective action and mobilization. The ethos of political change in South Africa has been participatory. Similarly, credible research efforts are expected to follow a participatory and “democratic” process. There is wide-spread agreement, for example, that community health promotion and education programs, including those directed at the country’s HIV epidemic, should be participatory and aimed at helping communities “take ownership” of the health problems and resources involved (Campbell, 2003). Consequently, there is a strong tradition of using various community-based, participatory and empowerment strategies to conduct research (Campbell, 2003; Motteux, Binns, Nel, & Rowntree, 1999; Williams et al., 2000; Campbell & Mzaidume, 2001). Furthermore, many community organizations and structures formed to challenge apartheid, function among their other roles, as gatekeepersintent on protecting communities from exploitive, non-participatory, or purely theoretical research.

CBPR’s commitment to placing health issues in their social, political, and economic context resonates strongly with the South African stakeholder. As our data will show, many South Africans are acutely aware of the link between their health and wellbeing and the country’s history of social, political, and economic discrimination. Projects that ignore or disavow these contextual ties are not likely to gain the full interest, support, and trust of the community.

The CBPR principle of seeking fundamental change also overlaps with the ongoing shift in South Africa toward community-based, primary health care (Benatar, 2004).

Study rationale

From a CBPR perspective, research questions should be formulated from the outset with direct input from and democratic engagement with communities. In our case, the dictates of available funding, our own research interests and expertise, and the high incidence of cervical cancer among Black and Colored women in South Africa led to our initial decision to explore the risk behaviors for cervical cancer, which include early onset of sex, sex with multiple partners, and cigarette smoking (Bosch, Munoz, & Sanjose, 1997; McBride, Scholes, Grothaus, Curry, & Albright, 1998). We aimed to conduct our research in an urban area located on the outskirts of Cape Town. This community is also one of the few ethnically diverse neighborhoods with considerable numbers of Blacks and Coloreds. This diversity lends itself to an exploration of ethnic and cultural differences and their relationship to people’s knowledge about and responses to the risks of developing cervical cancer.

In South Africa, cervical cancer is the most common cancer in Black women, the second most common in Colored and Asian women, and the fourth most common in White women (CANSA, 2003a). Rates for White South Africans are comparable to those found among Whites in the UK or US (CANSA, 2003b). The lack of screening resources is a particular problem in South Africa. Recent reports suggest that older, poor women living in the Cape Town area are particularly at risk for developing cervical cancer because they are not being reached through opportunistic screening efforts (Bradley, Risi, & Denny, 2004).

Efforts are now underway to improve women’s access to screening, minted by the South African government’s new cervical cancer screening policy that promises women 30 years and older three free pap smears in their lifetime (DOH, 2002). However, the effective and uniform implementation of this policy is not without expected difficulties. For example, a report in a Cape daily newspaper stated that at least one-third of women in Cape Town are still not being screened for cervical cancer (Smetherham, 2003). Problems include a low demand for screening among women, a nationwide shortage of nurses, overworked staff, and a lack of coordination among local, regional, and state administrations (Crawford & Everett, 1999). We therefore felt it was essential to consider primary behavioral prevention options for cervical cancer, including the possibility of educating young girls about the risk behaviors for cervical cancer.

Methods

We conducted a series of informal interviews, focus groups, and field visits to explore the feasibility and appropriateness of developing a cervical cancer prevention effort focused primarily on adolescent girls. Below, we describe our research methods in more detail.

Informal stakeholder interviews and field visits

In March 2002, as part of our initial effort to engage local stakeholders, we visited the community and met with a wide range of people, including local health professionals, school officials, members of local and regional government, service providers, academics, youth groups, health promotion organizations, clinic workers, traditional healers, and women’s groups. The goal of these meetings was primarily to introduce ourselves to these stakeholders, establish dialogue and credibility, and invite local critique and feedback of our interest in adolescent risk behaviors and cervical cancer. We also visited community schools, the local clinic, the library, informal social halls, local businesses, and other venues.

One important outcome of these visits was the formation of a community-based “reference team” aimed at providing the community with a forum for shaping, commenting on, critiquing, and helping to guide our research. The team included community members from the local Health Forum, the local library, two local school physicians, two local clinic workers, two members of the parent-teacher governing body, two university researchers, local educators, two local service providers (including LoveLife), government, and several cancer community workers. Members of the reference team were actively involved in the decision to conduct focus groups and how to conduct them and in ongoing discussions about the future direction and shape of the project.

Focus groups

Focus groups have often been used to conduct CBPR (Clark et al., 2003). They provide people with a structured opportunity to speak freely on issues pertinent to the research. We conducted 27 focus groups with 181 participants. Focus group participants included girls and boys in grades 8 through 10 (n = 112), mothers (n = 17), educators (n = 34), school support staff (n = 11) and community stakeholders (n = 7). Given our interest in adolescent risk behaviors, the four high schools in this community were understandably our most ideal research partners. We therefore met with the school principals, educators, and learners to introduce our project and elicit feedback and support. We also sought and received formal approval from the Department of Education to conduct the research.

A variety of strategies were used to select potential focus group participants. We used class lists from the four schools to randomly select adolescent participants from grades eight through ten. We selected equal numbers of Blacks and Coloreds, and girls and boys. Boys were included because of the interconnectedness of gender, sexuality, and adolescent health (Ampofo, 2001;Varga, 2001).

We convened a number of focus groups with adult women who were also mothers in order to better understand their views on female health. While we are strong proponents for the inclusion of men in reproductive and cervical health promotion efforts, we did not include men in the parent focus groups simply due to a lack of resources.

Mothers, educators, and school support staff were enrolled in the study on a volunteer basis. Half of the mothers whom we invited were the mothers of girls from the focus groups; the other half was identified by the educators. At each school, we targeted teachers who worked with students in the selected grades. In addition, the researchers held at least two informational meetings at the school to introduce the study to teachers and staff. We also conducted focus groups with the school support staff which included the secretarial, security, and cleaning staff. For the community stakeholder group, we selected participants based on their role, knowledge, and involvement with the community in general, and with youth, in particular. This group included a health worker, a member of the local government, a community development worker, an adolescent clinic volunteer, a librarian, and a community activist.

Obtaining informed consent from parents and children

Informed consent is critical to the ethical conduct of scientific research. It is also an opportunity to demonstrate a preparedness to engage and involve community members in the research. We obtained informed consent from all study participants. Language, literacy, and access issues informed our choice of consent procedures. Given that all school materials are sent out in English, we decided to keep our consent and assent forms in English. To ensure readability, we had the principals, some teachers, and several community members review the consent forms and suggest changes.

The informed consent process began with an informational meeting with the randomly selected youth participants. The meeting was held in a classroom after school, where we informed eligible subjects about the study and invited questions. This informational meeting was especially important given that few of the participants had any formal experience with research. These face-to-face meetings were conducted in English, Xhosa and/or Afrikaans. Meetings lasted 20–25 min and the researchers provided each student with several documents to take home: a cover letter from the principal introducing the researchers and the study, a consent form, and an assent form.

In an effort to address some of the issues relating to parents’ literacy, we sent out an outreach worker to visit the homes of parents who received the consent forms. Our goal was to understand the challenges that parents may have encountered with the consent form. According to the outreach workers, most parents understood the consent form, sometimes with the help of their child. Parents welcomed the home visits and asked clarifying questions about the study and the researchers. Seventy five percent consented to their child’s participation in the focus group. The assent rate for girls was 80% and for boys it was 60%.

We recruited 12 mothers from each school and received 10 signed consent forms. However, on the day of the focus group, only 42% of mothers attended the group session. These attendees suggested that transportation and babysitting issues may have prevented other mothers from attending.

Focus group moderators

The choice of moderators was critical to the research. We were committed to hiring young, local community members to facilitate the focus groups. However, few, if any, were specifically trained as focus group moderators. To address this challenge, we hired and extensively trained young community members. We then paired each of them with an experienced focus group moderator who, while representing the ethnicity and language of the participants, did not reside in the community. Additionally, we also hired and trained older local residents as outreach workers. Their primary task was to perform door-to-door outreach and to obtain informed consent. Again, we paired a Colored and a Black worker to do outreach together, in anticipation of possible language barriers (see below). Furthermore, due to the historical realities of racial discrimination and exclusion, we wanted parents to be aware that our research included members of both ethnic groups.

Developing focus group questions

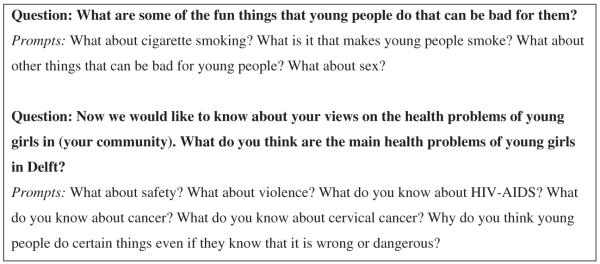

We developed the focus group questions to broadly explore the risk factors affecting the health and well-being of young girls. Facilitators were trained to ask a series of core questions and prompts aimed at enriching the data with secondary detail. The researchers developed a first draft of these questions and prompts, then offered them up for discussion and refinement by the project team in South Africa. The team included the local study coordinator and about eight focus group facilitators, most of whom lived in the targeted community. With their guidance and help, we translated and pilot-tested the focus group questions within the community. A sample of the questions and their accompanying prompts is included in Fig. 1 below.

Fig. 1.

Excerpts of girl focus group questions.

Challenges

Dynamics of race and language proved to be perhaps the greatest challenge to our focus group research. Whether we invited Coloreds and Blacks to participate in the same or different focus groups, and which language we chose to conduct the focus groups in would, we anticipated, send a strong political message. Post-apartheid South Africa stresses racial integration; yet, a focus group consisting of both Blacks and Coloreds might make communication difficult or even impossible given the lack of a common, neutral language to conduct the focus group in. Nevertheless, we set out aiming to conduct racially integrated focus groups using English as the medium of communication. English is taught at all schools in South Africa, and is widely spoken among both Blacks and Coloreds. Afrikaans is also widely spoken, particularly by Coloreds in the Cape Town area; however, the language has complex, turbulent associations with apartheid rule and a decision to use it in our integrated focus groups would likely have alienated Black participants.

We conducted an on-site review of the first three integrated, English-only focus groups in order to assess the level of input and comfort of participants with this format. Although they contained valuable material, the three focus groups were also punctuated by frequent silences and uncomfortable pauses, and moderators clearly had difficulty getting the two groups to talk with one another. We therefore proceeded by inviting Black and Colored youth to participate in separate focus groups, run in Xhosa and Afrikaans, respectively. A marked difference in the quality of participants’ responses was immediately evident. Conversations grew lively, and participants often exceeded the discussion time of 60 min. Many asked afterwards whether they could meet again to talk. The lack of any mention of racial tensions between Blacks and Coloreds in our focus groups suggested that language, rather than racial issues, accounted for the communication difficulties we identified in the initial three focus groups.

The focus groups with mothers and school support staff were held in their mother tongue, while the groups with teachers and community stakeholders were held in English. The Xhosa focus groups were translated into English and the translations verified by a professional translator. Because the Afrikaans spoken by our participants was often highly idiomatic and colloquial, we decided not to translate the original transcripts of the Afrikaans focus groups, but to have Afrikaans-speaking research assistants (RAs) lead the analysis of this portion of the data and produce summaries in English.

Data analysis process

Data analysis included several key components consistent with CBPR. The Afrikaans material was analyzed in South Africa by two RAs, and the translated English focus groups were analyzed by two RAs in the United States. This division of labor ensured that several of our South African staff continued to be involved in the project, while we benefited from community-based and local interpretations of the data. Our analysis was guided by the study goal of assessing the overall health and the factors affecting the health of young girls in the community. Data analysis was conducted using a workshop format, in which members of the research team collectively discussed the focus group data with the aim of identifying and summarizing the predominant themes and issues that were of concern to participants.

The steps

The data analysis began with the creation of comprehensive, substantive summaries of responses to each of the seven focus group questions. Each summary consisted of a quantitative list of response categories for each of the interview questions, and a qualitative synopsis of the participants’ responses. Finally, each summary included the research assistants’ personal interpretations of the responses to the question. We used the same process both in the US and in South Africa, with slight variations due to the local context and resources.

United States

Prior to each workshop, the research team, consisting of the two Principal Investigators (PIs) and two RAs, read the full transcripts for each particular focus group. One RA would prepare a detailed, three-part summary for each question, consisting of categories, synopsis, and subjective interpretations. For the first two focus groups, each of the two RAs summarized the same transcript and then merged their summaries. It was then determined that the summaries were similar enough that this verification process was unnecessary.

In the workshops, we read the summaries of each focus group question for accuracy, and discussed modifications. In general, the summaries did not require substantive changes. Nonetheless, the subjective interpretation portions of each summary were especially illuminating in that they often revealed the contextual biases of the RAs. Interpretations were discussed, but not corrected. After we reached agreement on the accuracy of the summaries for all focus groups, we performed content analysis to identify the common themes across all groups.

South Africa

Similar to the US data analysis procedure, two RAs were assigned to each transcript. The summaries were written in English. To establish coder reliability, and to replicate the role of the study investigators in the US as much as possible, a senior research associate was assigned to verify the accuracy and completeness of each summary. In addition, the PIs received and delivered regular feedback via telephone and email to the analysis team in South Africa.

Results

One hundred and eighty one (181) individuals participated in 27 focus groups.

Demographics of youth

One hundred and twelve students participated from four high schools. The average age was 15 and the majority (68%) was female. Most of them (74%) were eighth graders, 11% was in ninth grade and 15% was tenth graders. Almost half of them (47%) had lived in the community for 5 or more years while 19% had lived there for less than a year. Of the participants, 41% said that they speak Afrikaans at home, 34% reported that they speak Xhosa and 13% said that they speak both Afrikaans and English at home. The majority of participants (70.5%) reported that their fathers lived with them. The average family size was seven. Many had members of their extended family living with them. Next to the immediate family, aunts, grandmothers and uncles, were most likely to live with participants. At least half of the participants (51%) reported that their fathers were permanently employed while 38% of mothers were reported to have permanent employment.

Mothers

Seventeen mothers participated in four focus groups. The average age was 42 and the level of education ranged from fifth grade to high school graduate. Just over two-fifths of participants reported living in the community between 1 and 5 years or 6–10 years. Eighteen percent reported living there between 11 and 15 years. The majority of mothers (59%) reported speaking Afrikaans at home, 35% spoke Xhosa, and 5% spoke both English and Afrikaans at home. Forty one percent of mothers were casually employed, 24% had permanent employment and 24% were unemployed.

Educators

Thirty-four teachers participated from each of the four schools. The majority (68%) was female and 62% reported having post-graduate degrees. Almost half (47%) of them reported teaching for more than 5 years. The majority (68%) reported being involved in some form of extramural activities at school. Ninety-one percent of teachers reported living outside the community.

Support staff

Eleven support staff attended the focus groups. Their education level ranged from fourth to tenth grade. Half of the support staff had worked at their respective schools for more than 5 years while three were part-time. This group consisted of five security personnel, two administrative employees and four cleaning staff. Sixty percent of the participants resided in the community.

Community stakeholders

There were seven participants (two men and five women). At least half of them had some university education and half of them lived outside the community.

Focus group themes

The themes that emerged from the focus groups speak to the everyday struggles and concerns of young people and adults living in this community. They speak to people’s conceptions of health as a state that goes beyond individual physical and mental wellbeing, and to the wellbeing of the family, the neighborhood, and the community as a whole. Discussion of daily hardships, lack of employment and money, feelings of helplessness and impotency, and the pervasiveness of violence speaks to the broader context—the forces of social and economic marginalization—to which people alluded when thinking and talking about “health.” Below, we provide greater detail on these themes.

Poverty and maternal impotency

In the focus groups, parents expressed how poverty and unemployment challenge their role as provider on a regular basis. These parents talked about the complexity and fears of raising children with limited financial and external resources and how these structural conditions result in children’s risk behavior. One mother said: “That’s what makes our children naughty and incapable of listening and start robbing, you see. Because a child is not getting the things s/he’s supposed to be getting at home. You can give a child love as much you can, but if you can’t give him/her food that is cooked next door, and the dress that the other child is wearing, in this day and age most children can’t stand for that you see. So, crime groups come because of unemployment.”

Focus group parents talked about their fears that their children would succumb to the lure of easy money promised by selling drugs, stealing, and sexual favors. In particular, mothers talked about how sex is often used by young girls to barter for resources (food, money for clothes, drugs and alcohol), especially from older men. In all the mothers’ focus groups, participants discussed the taxi queen phenomenon. A taxi queen was described as a young girl who sits next to a male taxi driver and allows him to touch her while he drives around the neighborhood and city to transport passengers. One parent explicitly stated that poverty results in teenagers prostituting themselves to buy necessities at home. She said, “Maybe the mothers don’t have money for bread and such, so now the young girls involve themselves with taxis and give their bodies for money.”

Various participants including support staff and mothers made the association between poverty and the various health risks quite clear in the focus groups. By way of explanation, one mother said: “Our children [in this community] can be affected in the area of diseases, from that issue we discussed of struggling homes. It happens that when a girl is from a poor home, she gets a man this age to be her boyfriend, because perhaps that man has money, she wants these earrings you see. That man has money and he is way older than her in age. So that girls’ mind is on money and she ends up contracting a disease now, AIDS, she gets AIDS at that time. She gets the things she wants with her body let me say, because now she is doing business with her body. She has seen that I can’t afford it so she is trying in her own ways, so she gets a disease and she also gets these things.”

Furthermore, several focus group participants specifically talked about the poor housing and the over-crowding conditions that many of the school children live in. Teachers linked the lack of student motivation and performance to the poverty and home life experienced by some of their students. As one teacher said: “First of all motivating them, I’m motivating everyday, they’re very demoralized and you find that a lot of them feel that they—they’re actually, before they even accomplish—they feel low, they feel a very low self-esteem, they feel that they’re in that situation where they’re staying, they’re hungry, and their parents are not working and that makes them very—why should I be coming to school? Why should I be educated?”

Besides lacking the internal resources to provide, participants were quick to point out the barrenness of their environment in providing children with recreation opportunities. Parents viewed the absence of recreational facilities as further impeding their role as parent.

Barriers to health

In addition to poverty, participants talked about violence, substance abuse, sexual violence, early onset of sexual activity, gang activity and teenage pregnancy. Regarding youth violence, one mother said: “The youth is on a rampage out there, they are killing and shooting, they have guns and whatever, they are trying the drugs, it’s everything. They want money to buy these drugs, the youth today are killing, they drink alcohol and all that.”

Substance abuse

Talk about substance abuse included smoking cigarettes, drinking or selling alcohol, and using or selling marijuana, crack cocaine or ecstasy. Most participants linked substance abuse to other youthful behaviors and motives. Selling marijuana and other drugs was seen as quick way to make money for many young people. Parents saw substance abuse as widespread among the youth, and spoke vehemently of drug dealers exploiting young kids. Parents felt that both boys and girls fall victim to drug use, and become easy prey for drug merchants who use the promise of easy money as a key enticement. This view was reiterated by the support staff, who said that both girls and boys smoke and sometimes use marijuana on school grounds. The shebeens (typically a residential home transformed into an informal bar that sells alcohol, plays blaring music and have several pool tables and other games) were viewed by many participants, especially adults, as assisting in the destruction of youth. Young people were more likely to acknowledge the importance of at least being able to access some recreation in the neighborhood. Several said the shebeen was one of the few places in the community where young people could have “fun.”

Violence

The majority of participants described the pervasiveness of violence in their neighborhood at length. The lack of safety and constant threat of personal violence or attack was frequently mentioned in all focus groups. Participants did not so much acknowledge a fear of the violence, but rather a resigned inevitability and profound awareness of it. As one male participant put it “there is no safety for a person [here].” Another participant summarized the pervasiveness of the violence as “we are so used to the shootings. We sleep right through it.” Support staff and teachers inparticular are witnesses and sometimes victims of the violence on school grounds. Several teachers either reported incidents of being victims of violence or stories of their colleagues who had been victims of violence. The support staff mentioned that violence was almost a daily occurrence at school. According to them, vandalism at school was a huge problem.

Gangs

Gang activity was also mentioned as a huge problem, and several participants talked about the various ways in which gang violence affected their daily living. Several youth and parent focus group members talked about the perceived financial and social status rewards of belonging to a gang. Interestingly, compared to the other groups, the male participants talked much more about gang activity and how they are often victims of gang violence. One male participant said: “then they quarrel, then maybe at first they take out knives, and then they decide a knife takes too long, then they take out the guns. You see here in [this community] guns are play things for children, they shoot each other. And then it turns into a gang war.”

Sex

Participants primarily talked about sexual violence, coercion, and unsafe sex. Although youth participants knew many facts about unsafe sex and HIV-AIDS, according to these participants, unsafe sexual practices appeared to be the norm. In reference to peer pressure, one boy participant said about having sex without a condom: “You’re like okay you use a condom every time, and the guys are telling you, ‘no that thing is nice without it.’ And you think ‘hey, I haven’t done it without it, let me go and feel what it’s like.’ You feel it for the first time, and you feel that it’s nice, and then you will be able to talk to the other guys and say, ‘No, now I know that thing, I know that its nice’, and then you continue doing that on and on, and the condom can wait.”

The many legacies of apartheid

The brutality and violent behaviors of the police during the apartheid era are further marred by the perception that the police are not doing enough to combat present day crime. Mothers especially were frustrated with the lack of police assistance and police credibility. As one mother said: “The police stations gives us a hard time, it doesn’t help at all, because there’s a lot of corruption because we can’t work with the police. And I want to know if the police in [this community] are for White people only? Because we don’t get Black police.” Participants felt that the police had little resources, power or resolve to deal with the crime and violence effectively. Some of the participants said that the police discriminate against Black residents. Consistent with the lack of faith in the police, there seems to be widespread support for using vigilante justice. One participant spoke of the community’s response to violence: “when they hear that there’s a thief, they don’t think about the law, they think about beating the skollie (bad guy) to death, that’s what we live withy so that’s another thing that causes other things on the side. Because there are many corpses of children who get killed.”

In some of the focus groups, participants blamed the disintegration of the family on the indiscretions of the apartheid regime. The teachers talked about how many of the neighborhood residents are transplants from rural areas, with children often migrating apart from their mothers and fathers. One teacher talked about the instability of the family and said: “There are very few of them in this community, there are few family structures that are what you call normal, that you find that there’s nothing wrong there. There is no mother–father–children kind of set up, you know there are guardians, there are sistersy”

Sources of strength

Despite the profound environmental challenges, many participants also talked about the positive elements in their community. Teachers talked about the joy of making a difference in students’ lives and of the pride they feel when students excel beyond the boundaries of their circumstances. Participants reported having a strong support network of friends and family. In most of the youth groups, friends were at the top of the list in terms of providing trusted advice and support. However, surprisingly, mothers were also near the top of the list as being trusted advisors and confidantes. Mothers emerged as steady and wise support people despite their sometimes feared reputations as the moral mainstays of the family. When asked whom she would go to if she had a serious problem, one female participant said: Okay, if I had a problem I’d run to my mother, because I know that if I had a problem she’s the one who knows me, a person who knows me who will understand me when I tell her about this problem, and set me on the right path.”

Fathers were not talked about much. Only a few youth participants mentioned the important role of their father in their lives. Other important support persons mentioned were siblings, aunts, teachers, and service providers such counselors, social workers, and teachers. Furthermore, several participants reported belonging to various athletic and community groups who were involved in volunteer activities. Students and support staff talked about the drama and prayer groups at school and how many students were involved with these activities despite the negative influences in their environment. One youth participant said: “Okay, I have a group that I have joined here [at school], the dramatists, its about drama, we do drama, things that happen in the community, its about the life we live, we express it in the drama we perform, we keep ourselves busy with that, I see that there’s no future in that, so it’s a good thing, and its here at school.”

Mothers talked about the joy of having daughters, how daughters helped to alleviate their daily stressors, and especially how their children embodied mothers’ dreams for a better future. Finally, despite the many challenges that the focus group participants so freely described, they talked as eloquently about their joys, their relationships, about studying hard, falling in love, wanting to become doctors, their music, and hanging out with friends.

Discussion

The goal of our research was to examine the multiple factors that affect the health and wellbeing of young school going girls in a peri-urban community in Cape Town. The goal was to explore and understand the context within which we needed to develop a primary prevention program focused on the risk behaviors for cervical cancer. However, due to the dynamic and cyclic nature of community-based research, our conceptualization of the research problem underwent a major transformation.

The voices of multiple stakeholders offered several fundamental lessons: (1) health-seeking behavior occurs in a context shaped by economic, structural, and interpersonal conditions, (2) health interventions need to address the multiple anxieties and lived reality of the target group, and (3) a narrow focus on the long-term risk for cervical cancer among adolescent girls has limited value.

The strong association between risk behaviors and poverty has been strongly established (Campbell & Mzaidume, 2001; O’Hara-Murdock et al., 2003). Yet, often interventions are developed that have unrealistic expectations or outcomes that are so far removed from what people are able to do. Focus group participants talked about the logical link between a lack of money and participation in certain risk behaviors such as selling drugs, being a taxi queen, and committing acts of violence. That is, participants pointed to the forms of “structural violence” (Farmer, 2003) that lead to and reinforce violence, hunger, crime, sexual favors, drug peddling, and other problems. Equally compelling, participants described a strong culture of resilience, which includes mobilizing community organizations to target social problems and engaging in normal, day-to-day activities. The duality of life in this community is characterized by the forces of fear, poverty, and violence on the one hand and resiliency, abundance of community spirit, and pragmatism on the other hand.

The success of our future efforts to promote cervical health in this community will be determined, in many respects, by our degree of responsiveness to this duality. On the one hand, our work needs to acknowledge the elements of poverty and suffering in the community. On the other hand, it will need to tap into the community’s “can do” spirit in order to mobilize women, for example, to be screened for cervical cancer. In a study examining a peer led HIV/AIDS prevention program for women in a South African settlement, these authors also acknowledge the valuable internal resources of community members, and the importance of designing intervention programs that address the social conditions that perpetuate risk behaviors (O’Hara-Murdock et al., 2003). Becoming only focused on the structural impediments to behavior change would certainly be short-sighted; a more comprehensive approach would be to recognize the barriers as well as the high levels of community resiliency and capacity for change.

The third point focuses on what we learned in this community regarding the initial goal to develop a primary prevention program to reduce the risks for cervical cancer among young girls. Most important, as international researchers, we felt that it was more effective to work alongside South Africa’s policy than in opposition to it. Any program educating young girls on cervical cancer must necessarily include information on pap smears. However, in South Africa, sexually active young girls under 30, who do not have other medical problems, are not able to get free pap smears. Furthermore, we found that many of their mothers were not knowledgeable about cervical cancer. The conundrum we had to address were the ethical issues associated with focusing on only young girls when, in South Africa, older women are far more at risk for developing cervical cancer. Although more young girls are being diagnosed with cervical cancer the overall rates for young girls are low (Fonn et al., 2002). The answer to this conundrum was clear. Young girls have a right to be educated about the risks of cervical cancer; mothers in this community were undoubtedly at a higher risk for developing cervical cancer; and pap smears were available to them. Based on our study findings, the needs in this community, and South Africa’s cervical cancer policy, the clear option for us was to work toward developing an intervention that would include both girls and mothers.

Challenges of CBPR approach

There are several challenges facing the CBPR researcher, primarily because this philosophy steers us to work in communities confronted by multiple concerns and priorities, some of which may not mesh with the researchers’ agenda.

Research and service delivery tension

The tension between research and service delivery is conspicuous as well as compelling. This conflict addresses the core of the distinction between insider and outsider, rich and poor, academia and community. In international research, the divide between rich and poor, privileged and needy iseven more evident. In our research, we used every opportunity to let the community stakeholders know that the continuation of our work was dependent on securing funding and that we were equally interested and committed to issues of capacity building and sustainability. These reminders are ultimately mediated by the community’s needs and conditions. At a minimum, the CBPR researcher must be cognizant of these ethical challenges. We found that working closely and learning from local researchers and stakeholders who had experience with the service delivery-research dilemma was helpful. In the early stages of the research, the “deliverables” can be in the form of training community members. Researchers can “deliver” by providing consultation and training to community members and service providers who are able to lobby for resources. Additionally, community members can assist in the important task of agenda setting and priority development. Finally, researchers ought to carefully consider the balance between long-term data collection and implementing interventions that could alleviate some of this tension.

Effective community engagement

Community engagement, a key principle of CBPR, is a challenge to many researchers. Such engagement extends beyond the inclusion of visible, well-known, and research savvy stakeholders. In our research, we met with a variety of non-mainstream community members including shebeen owners, traditional healers, cleaners, and security staff. In addition, the importance of strong communication skills and cultural knowledge in CBPR projects cannot be underestimated. International researchers who work in developing countries will find that there is a strong emphasis on relationship building.

Perhaps the most fundamental shift in our research was marked by the adoption of “cervical health” as a key guiding concept as well as an overall perspective for our research. This is a term that local stakeholders suggested to us, to reflect the fact that poor women in South Africa generally face health challenges that far exceed the boundaries of, and interventions for, cervical cancer. These challenges include other reproductive diseases, HIV-AIDS and the specter of vertical transmission, sexual violence, and other issues. Our future goals in this community include developing a cervical health intervention that incorporate adult women into our research question and we are committed to developing a multigenerational perspective (mother and teenager) in place of our earlier focus only on adolescents. In conclusion, cervical health as a concept, philosophy, and intervention takes into account the many daily struggles of living with multiple health anxieties including poverty, crime, violence, and unemployment. Cervical health acknowledges that health-seeking behavior is mediated by everyday stressors, including poverty, hunger, and violence. Cervical health is indeed still a focus on cervical cancer prevention and the key objective of increasing the number of women obtaining screening. However, an intervention on cervical health will take into account, for example, how gender violence or the competing needs and demands of the family, may mediate a women’s chances of actually being screened. How to operationalize the concept of cervical health will be the key challenge facing our future efforts in this community. Another challenge includes whether the term cervical health will serve to obscure the very real issue of cervical cancer in the community or whether through this broad conceptualization, understanding of cervical cancer will be enhanced. Nonetheless, the adoption of an insider term such as cervical health is a vital first step in gaining the interest and trust needed to conduct successful community-based, participatory health interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was approved and supported by the Internal Review Board of University Hospitals and Case Western Reserve University (#07-03-35) and the Department of Education of the Western Cape. We could not have conducted this research without the cooperation and support of the focus group participants and facilitators, the high schools in the community, the two public libraries, and members of our reference team, among others. We would also like to thank Drs. Lynn Denny, Alan Flischer and Laura Siminoff for their support and encouragement. We also acknowledge the work of our research assistants during the data analysis process. They are Berlina Wilschut, Liezl Goeieman, Mara Buchbinder and Michelle Nebergall. Finally, the generous financial support of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center and the R25 Fellowship Program were critical to the success of the research.

References

- Ampofo A. “When men speak women listen”: Gender socialisation and young adolescents’ attitudes to sexual and reproductive issues. African Journal Reproductive Health. 2001;5(3):196–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey D. Using participatory research in community consortia development and evaluation: Lessons from the beginning of a story. The American Sociologist. 1992 Winter23:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Benatar S. Health care reform and the crisis of HIV and AIDS in South Africa. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(1):81–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr033471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch F, Munoz N, Sanjose d. Human papillomavirus and other risk factors for cervical cancer. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 1997;51(21):268–275. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(97)83542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley J, Risi L, Denny L. Widening the cervical cancer screening net in a South African township: who arethe underserved? Health Care for Women International. 2004;25(3):227–241. doi: 10.1080/07399330490272732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Mzaidume Z. Grassroots participation, peer education, and HIV prevention by sex workers in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(12):1978–1986. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C. “Letting them die”: Why HIV/AIDS prevention programmes fail. The International African Institute/Heinemann; Oxford and Indiana: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- CANSA . Cervical Cancer: Numbers and Incidence. Cancer Association of Southern Africa; 2003a. http://www.cansa.co.za/registry_cervix.asp. [Google Scholar]

- CANSA . Cervical Cancer: Ranking. Cancer Association of Southern Africa: 2003b. http://www.cansa.co.za/registry_cervix.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Clark MJ, Cary S, Diemert G, Ceballos R, Sifuentes M, Atteberry I, Vue F, Trieu S. Involving communities in community assessment. Public Health Nursing. 2003;20(6):456–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A, Everett K. Cervical cancer screening situational analysis. Cancer Association of South Africa: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- DOH . National guideline on cervical cancer screening program. The Department of Health; South Africa: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Elden M. Sharing the research work: Participative research and its role demands. In: Reason P, Rowan J, editors. Human inquiry: A sourcebook of new paradigm research. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P. Pathologies of power: Health, human rights, and the new war on the poor. University of California Press; California: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fonn S, Bloch B, Mabina M, Carpenter S, Cronje H, Maise C, Bennun M, du Toit G, de Jonge E, Manana I, Lindeque G. Prevalence of pre-cancerous lesions and cervical cancer in South Africa—a multicentre study. South African Medical Journal. Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 2002;92(2):148–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D, Metzler M. Implementing community-based participatory research centers in diverse urban settings. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):488–494. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall P, Rotimi C. Ethical challenges in community based research. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2001;322(5):259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride C, Scholes D, Grothaus L, Curry S, Albright J. Promoting smoking cessation among women who seek cervical cancer screening. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;91(5):719–724. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motteux N, Binns T, Nel E, Rowntree K. Empowerment for development: Taking participatory appraisal further in rural South Africa. Development in Practice. 1999;9(3):1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nama N, Swartz L. Ethical and social dilemmas in community-based controlled trials in situations of poverty: A view from a South African project. Journal of Community and Applied Psychology. 2002;12:286–297. doi: 10.1002/casp.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara-Murdock P, Garbharran H, Edwards MJ, Smith MA, Lutchmiah J, Mkhize M. Peer led HIV/ AIDS prevention for women in South African informal settlements. Health Care for Women International. 2003;24:502–512. doi: 10.1080/07399330303975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petras E, Porpora D. Participatory research: Three models and an analysis. American Sociologist(Spring) 1993:107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn S. Protecting human subjects: The role of community advisory boards. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(6):918–922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon K, Welsh J, Kreiswirth B, Forrester J. Participatory action research from the inside: Community development practice in East St. Louis. American Sociologist(Spring) 1993:69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Smetherham J. Cape Times. Cape Town, South Africa: 2003. Cervical cancer danger as women fail to be tested. [Google Scholar]

- Stoecker R, Bonancich E, editors. Guest Editor’s Introduction: Participatory research, part II. The American Sociologist(Spring) 1993:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton R, Ramphele M. The quest for community. In: Boonzaier E, Sharp J, editors. South African keywords: The uses and abuses of political concepts. David Phillip; Cape Town and Johannesburg: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Varga C. The forgotten fifty per cent: A review of sexual and reproductive health research and programs focused on boys and young men in Sub-Suharan Africa. African Journal Reproductive Health. 2001;5(3):175–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, MacPhail C, Campbell C, Taljaard D, Gouws E, Moema S, Mzaidume Z, Rasego B. The Carletonville-Mothusimpilo Project: Limiting transmission of HIV through community-based interventions. South African Journal of Science. 2000;96:351–359. [Google Scholar]