Abstract

In this paper, we consider some of the challenges associated with the ethical need to conduct locally relevant international health research. We examine a cervical cancer research initiative in a resource-poor community in South Africa, and consider the extent to which this research was relevant to the expressed needs and concerns of community members. Results from informal discussions and a series of 27 focus groups conducted in the community provide insight into the community’s needs and concerns, and its recommendations for how the research could be made more relevant to the community. We discuss these findings in the context of recent theory and literature on the role of community engagement in promoting local relevance and responsiveness in community-based health research. We anticipate that the paper’s findings may help international health researchers better identify and assess the challenges of conducting locally relevant research across major global gaps in wealth and health.

Keywords: International health research, Research ethics, Cervical cancer, Community health, South Africa, Community engagement

Introduction

Scholars in the social sciences, bioethics, public and community health, and other fields have recently urged that health research, particularly international health research, demonstrate greater relevance to local needs, concerns, and interests (Benatar, 2002; Bhutta, 2002; Emanuel, Wendler, Killen, & Grady, 2004; Macklin, 2004a, 2004b; Marshall, 2005). They have pointed to forces that work against the design and conduct of locally relevant international health research, including the so-called “10/90 gap,” which refers to the statistical finding that only ten per cent of worldwide expenditure on health research and development is devoted to the problems that primarily affect the poorest 90% of the world’s population (Davey, 2004).

Although the world now spends considerably more on health research than was the case 16 years ago when the 10/90 statistic was first calculated, experts agree that there is still “a massive under-investment” in health research relevant to the needs of low- and middle-income countries (Davey, 2004). What is meant by “relevant research” is often unclear and shifting, however. In some cases, health-related research has the potential to significantly ease the local and global burden of a health problem over the long term, but lacks immediate relevance for the people, communities, or countries already impacted by the problem at hand (Chua, Ford, Wilson, & Cawthorne, 2005; Singh & Mills, 2005). In other cases, a research study may be viewed as instantly relevant on the grounds that it offers local participants access to a scarce drug, treatment, or other health care resource. This assessment may be premature, however, since research-related interventions can involve significant risks, can be extended to some research participants and not others (i.e., in placebo-controlled interventions), and can be abruptly with-drawn when the research ends.

This paper offers a critical examination of the concept of relevance in international health research, through the lens of research that we conducted in a resource-poor community in South Africa. Our long-term goal was to help inform local women about cervical cancer and encourage them to take advantage of South Africa’s relatively new (Department of Health South Africa, 2002) cancer screening policy, which entitles South African women 30 years of age and older to three free preventive pap smears in their lifetime. We aimed to extend our health promotion efforts to younger women and adolescent girls, who did not yet qualify for free pap smears and who might wish to take other steps (e.g., minimizing sex with multiple partners, getting a paid-for pap smear) toward protecting themselves against the risk for developing cervical cancer later in life.

We considered these goals highly important and relevant given that, in South Africa, the age-adjusted cervical cancer incidence rate for every 100,000 women (31.08) is almost double the rate (13.1) for women in the United States (13.1) (US Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2005). Cervical cancer also affects proportionally more Black South Africans than other races, particularly whites, among whom the incidence rates for cervical cancer are as low as those of American women generally (The National Health Laboratory Service, 1997). From this standpoint, our research plans were also relevant to the larger South African effort to narrow the country’s disparities in health and health care.

From another perspective, however, our focus on cervical cancer and cancer prevention more generally had limited or even questionable relevance. We suggest that this perspective is evident in our South African research community’s reactions to our research plans, in its assumptions about our capacity to provide services to the community, and, in its prioritization of unemployment, poverty, youthful crime and violence, HIV/AIDS, and other problems over cervical cancer and cancer generally. Findings from our informal discussions with community members as well as from a series (n = 27) of focus groups that we conducted in the community are presented to illustrate the community’s articulation of a set of interests, needs, and concerns that was significantly at odds with our narrowly conceived study of cervical cancer and cancer prevention.

We go on to discuss the ethical responsibility of researchers to address these kinds of conceptual differences or disconnections, including through processes of community collaboration and engagement. We point out that such processes are no magic bullet for resolving conflicting perspectives of the relevancy of research, and that they may even generate additional ethical challenges for researchers. However, by providing, among other things, opportunities for local stakeholders to comment on a research design, discuss their broader needs and concerns, recommend changes to the research, and get involved in the research process itself, researchers may enhance the potential for mutual agreement on the local relevancy of their research.

We anticipate that this exploration may help other health researchers better identify and assess the challenges of conducting locally relevant research across major global gaps in wealth and health.

Background

Deciding against a research question

A growing body of literature suggests that community-based health promotion efforts are most likely to succeed if they gain input, support, and cooperation from the communities involved (Campbell, 2003; Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Minkler, 2004; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Motteux, Binns, Nel, & Rowntree, 1999; Speed, 2006; Williams et al., 2000). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) calls for openness and flexibility on the part of researchers, as a result, we intentionally did not formulate a specific research question or set of hypotheses prior to visiting and dialoguing with the community. This approach has the advantage of demonstrating to communities that they have a central role to play in shaping the focus and anticipated outcomes of a research initiative. Below, we detail how we opened up our research plans and ourselves to this level of community involvement, before turning to a summary and discussion of our findings.

Community engagement

One way in which researchers exercise discretionary power is through their selection of a community to conduct research in. We first considered working in one of several older, more established, Black communities outside Cape Town, because of indications that cervical cancer was as much a problem in this area as elsewhere in South Africa (The National Health Laboratory Service, 1997). However, after visiting some of these communities and learning that they were close to being disproportionately researched and resourced, we chose to look elsewhere. The community of Masidaal,1 by contrast, was a younger (founded through forced removal in the early 1980s) community of 37,000 Black and Coloured2 people, who reportedly lacked many essential health care resources and had not attracted many health researchers and interventions.

Our (Simon and Mosavel’s) first visit to the community suggested that Masidaal was, in fact, both under-resourced and under-researched. Community members whom we met and talked with volunteered that the community had been “ignored” and “overlooked” by other health researchers, policy makers, and service providers, and that our interest in the community was particularly welcome as a result. Masidaal also quickly provided us with a cautionary tale of the everyday challenges of living and working there. Driving down its main road for the first time, we spotted a crowd gathering around the body of a teenage girl. We learnt that she had been shot dead and robbed of R20 (about four US dollars) just minutes earlier, when she refused to hand over the money to her killer.

Over the course of several weeks, we met with people from different sectors of the community. We spent time in both the Black and Coloured neighborhoods of the community and its four high schools, informal social halls, local businesses, two libraries, churches, and other social crossroads. We introduced our research plans to the Masidaal Women’s Forum, a committed but under-resourced grassroots organization concerned with promoting the health and welfare of women in the community. Because we planned to work closely with local providers of pap smears, we also toured the primary health care institution in the community, the Masidaal Clinic, and shared our long-term plans with its directors and staff. Finally, we asked the community to help us organize a community advisory board (CAB) consisting of community members, local health care providers, community health experts from a local university, and other stakeholders, to help steward the research. We anticipated that the committee would meet quarterly in Masidaal, and serve as sounding board for local concerns and interests in the project. We took these and other steps as part of an effort to create opportunities for the community to get to know us, to ask questions and provide feedback on our research plans, and to build rapport and mutual trust.

Focus group methodology

Why focus groups?

Our informal meetings and discussions with community members gave us an opportunity to get a sense of people’s everyday needs, concerns, and interests. Many of these concerns were directed at the problems faced by youth in Masidaal, so we decided to conduct a more formal study to explore these concerns, among others. We consulted the CAB on the possibility and appropriateness of conducting a series of interviews, surveys, or focus groups in the community, to explore people’s—including young people’s—views and attitudes toward life and living in Masidaal, and toward health and wellbeing specifically.

The CAB immediately problematized the survey option on account of low literacy levels in the community, particularly among adults who had not benefited from a formal education under apartheid. CAB members also felt that interviews might make many community members uncomfortable because of their probing, individualistic format. The idea of conducting focus groups was found to be most appealing because it resonated with people’s preference in this community for group-based activities. Accordingly, we sought approval for, planned, and conducted a series (n = 27) of focus groups with a total of 181 community members. These community members were selected and invited to participate in various ways.

Sampling

A large randomized sample of high-school girls and boys (n = 112) was included, for two reasons: (i) to explore our long-term interest in empowering younger women who did not qualify for free screening to take steps to protect themselves from the risk of developing cervical cancer later in life; and (ii) to explore people’s concerns, expressed to us during our informal discussions, that the youth in this community faced serious and unique challenges to their health and wellbeing. Boys were included in this random sample because we anticipated that gender relations would impact both these areas of interest. Equal numbers of Coloured and Black students were selected.

Focus groups were also conducted with a sample of adult women/mothers (n = 17), educators (n = 34), high school support staff (n =11), and several other community stakeholders (n = 9), including two members of local government, two community development workers, an adolescent clinic volunteer, two librarians, and two community activists. The adult women/parents were included in order to gain an initial understanding of women’s needs and concerns in the community, including the potential burden of parenting. Educators and school staff were included because of their under-standing of the challenges of teaching and learning in the community. The other participants were included on the recommendation of our CAB, which felt that these individuals could bring an additional perspective to the issues facing people in Masidaal. Convenience sampling was used to select participants for this proportion of the focus groups. The table below summarizes the composition of the focus groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Focus group participants and number of groups

| Participant groups | Number of participants |

Number of focus groups |

|---|---|---|

| Girls in grades 8–14 | 76 | 9 |

| Boys in grades 8–14 | 36 | 5 |

| Adult women/mothers | 17 | 4 |

| High school educators | 34 | 4 |

| High school support staff | 11 | 4 |

| Other stakeholders | 9 | 1 |

| Total | 183 | 27 |

Informed consent

Our informed consent process was developed with input from the advisory board, school administrators, and other community members. Fieldworkers from the community were invited, hired, and trained to help administer the process. We began with school-based informational meetings to inform selected boys and girls about the study. These meetings were conducted in the home language of the students (either Xhosa, Afrikaans, or English) and were held after school hours. The study was explained in easy-to-understand terms and questions and comments were invited. Students who remained interested in the study after this meeting were asked to convey some written information about the study to their parents. Since there was no guarantee that this information would reach or be read by a parent, fieldworkers followed up with home visits to parents during which they discussed the study with parents and invited questions and comments. They then asked interested parents to give written permission for their child’s participation, and/or for their own participation. Written consent was obtained from all participants, including all high school students who participate in the study.

Focus group content and process

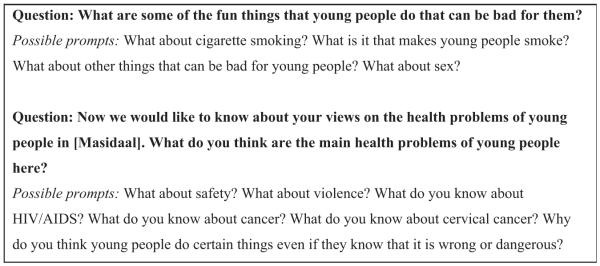

The focus group discussions were structured around the theme of “health and wellbeing in Masidaal,” with an emphasis on young people. Focus group questions were discussed, scripted, and pilot tested with the help of community-based project staff, who provided valuable advice on what kinds of questions to ask and how to ask them. Six community members were hired and trained to serve as focus group moderators. Moderators were paired with focus group participants on the basis of comparability in gender, age, and, linguistic and ethnic background. Each moderator asked a number of primary, open-ended questions, followed by a series of “prompts” aimed at exploring participant responses in greater depth, if this was required. The same questions were asked in all 27 focus groups, with minor rewording of some questions to reflect differences in focus group composition. The following is an example of the kinds of questions that were asked (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Example of questions asked of youth.

The focus groups with high school students were conducted at the high schools, after hours, and in a class room made available to us by the school principal. The other focus groups were conducted at different venues in the community, including a private room in the local library. Focus groups were audiotaped, lasted an hour on average, and included between 6 and 8 people each.

Data management and analysis

Word-for-word transcripts of each audiotaped focus group were created and then validated by a second round of listening to the tapes. The transcripts were analyzed by two trained research associates (RAs) in South Africa and two in the US, and by two of the authors (Mosavel and Simon). This division of labor ensured that several of our community members/project staff continued to be involved in the project, while we benefited from their community-based and local interpretations of the data. A number of different analyses were carried out on all 27 focus groups, and on some subsamples.

For the purposes of this paper, the analysis included all 27 focus group transcripts and was limited to any mention in the transcripts of problems and challenges confronting the community in general and youth specifically, and on cervical cancer and cancer generally. Each transcript was read and summarized for the above information by at least two RAs, who then compared and combined their findings to create a single master summary. This master summary became the primary source of data for the present study, however, the original transcript was frequently consulted to put the summarized material back into context.

Findings

Informal discussions and observations

A key finding to emerge from our initial engagement of the community of Masidaal was that our role as researchers was immediately confused, or conflated, with that of service provider. People commented frequently and straightforwardly that they were “grateful” or “happy” that we intended to provide “money” and “services” to the community. They commented that, as “Americans,” we surely had plenty of money and other resources to share with the community. We countered this view by saying that we were not service providers, but academics hoping to conduct research, which we construed as “finding out more about cervical cancer in Masidaal.” We pointed out that we expected this research to result in a partnership aimed at “doing something positive about” cervical cancer, but that this would be contingent on further funding, community interest, and other factors. The perception that we were service providers persisted, however, including among some of the people whose views we tried to change on this matter.

Our community engagement process also drew our attention to an important community perception, namely that our focus on cervical cancer was too narrow and limited. Stakeholders openly recommended that we focus instead on “cervical health.” They explained that the concept of cervical health respected the fact that South African women faced many different health issues and challenges, and not just one disease of the cervix. They added that, whereas “cancer” would engender fear and worry, “cervical health” would give our work a more positive spin. This was considered an important step in a community where people “already have so many things to worry about.”

Focus group findings

Our focus groups findings call attention to the many things that community members have cause to be worried about. They also suggest that people perceive cervical cancer with little immediate cause for concern, given the multiplicity of other issues and problems in their lives. This perception did not appear to be related to a lack of awareness of cervical cancer and the risks it posed for women. Almost all adult women who participated in our focus groups reported knowing something about cervical cancer, or someone who had developed cervical cancer.

Given this level of knowledge and awareness, discussions of cervical cancer and cancer generally were surprisingly brief. Most efforts by moderators to stimulate discussion on the topic of cancer met either with silence, brief commentary, or an indication from the group that it wanted to discuss other things. In the following extract, for example, the moderator tries for a second time to orient the discussion toward cancer. The group had been busy discussing views on HIV/AIDS in the community in response to a prior, open-ended, question on the “health problems” facing young people in the community:

Moderator: Okay, okay, great, you guys know about AIDS. What do you guys know about cancer?

[Silence]

Participant #1: Oh, cancer

Moderator: Cancer.

Participant #1: When you have HIV—I mean when you have AIDS, you can develop these diseases easily.

Such reorientations of the discussion away from cancer and back to HIV/AIDS or other concerns were characteristic of the other focus groups, as well. With little need for moderator encouragement, participants talked at length about the links between HIV/AIDS, sex and rape, poverty, and unemployment, among other factors. They talked about the lack of employment and money as incentives to girls as young as 12 for engaging in sexual favors and full-time sex work. A high school teacher who participated in our focus groups explained that sex work was often a way for a girl or woman to help support her family, and not just to earn money for herself. These women routinely risked rape, physical abuse, and HIV/AIDS.

Gangs and gang activity were discussed at great length. Gangs reportedly provided an attractive alternative to a jobless future, providing one of the few ways in which older boys and young men in particular could access money, food, clothing, and a modicum of self respect.

Alcohol and drug abuse were said to be growing problems in the community. Informal social halls known as shebeens and jukeboxes reportedly were springing up in neighborhoods across the community, selling liquor to minors and turning a blind eye to drug deals and sex work. Many youth were said to be “hooked on” drugs such as “dagga” (“marijuana”), Ecstasy, and “tik-tik” (a type of methamphetamine), which in turn was linked to an increased risk for sexual violence and diseases such as HIV/AIDS.

Public spaces and recreational areas, of which there existed few in the community, were said to be unsafe and unusable, even during the daytime. Although the public schools were considered safe compared to other places in the community, students complained of gang activity and violence in the schools, too. Girls said that female gangs often accosted them during and after school to demand jewelry or money, while male gang members sexually harassed them. Younger boys said that they were often bullied by older gang members; one boy said: “Anytime they want to, they throw us onto the table and hit us very hard. My head was already many times fat with pain.”

Teachers at the local high schools described daily gang fights, vandalism, and theft in the schools, and complained that the schools had become unsafe, uncomfortable, and difficult to teach and learn in as a result. Some teachers said they had been threatened or hurt by students. “A few years ago the students threw a brick through the window and my fingers were broken,” one teacher recalled. Asked when he hoped to graduate from high school, one boy in Grade 8 responded: “In four years from now. If I am still alive.”

The community was said to lack essential resources to deal with these and other problems. School administrations lacked the funds to hire more security to protect teachers and students. Medical attention for victims of sexual assault, rape, and violence generally had to be sought at the local clinic, which was said to be severely overstretched and understaffed. Little to no psychological counseling was available for victims of violence, and the local police force was said to be largely unconcerned about promoting community safety. A school principal, summing up the situation in Masidaal, told us: “This is a community in crisis.”

Discussion

Should we even be conducting research in Masidaal?

Community-based research frequently occurs in the context of multiple and intersecting social, political, and economic problems. In parts of Africa, the combined force of these problems threatens not just the wellbeing of individuals and families, but the social fabric and functioning of whole communities and societies. This was a theme we heard expressed in virtually all of our discussions with people in Masidaal, and one that raises important questions about the ethics, process, and outcomes of community-based health research.

Perhaps the most fundamental of these questions is whether research should even be conducted in communities gripped by crisis. There may be legitimate reasons why it should not be. For one, it may be arguably more appropriate and just for foreign governments, institutions, and researchers to prioritize people’s immediate needs such as lack of employment, money, and basic security before turning to the task of developing evidence-based health care tools and systems. Doing things the other way round as we find ourselves doing in Masidaal, may make the development of these tools and systems that much more challenging, costly, and difficult to implement.

On the other hand, there may be no simple alternative but to proceed with research using the funds and other resources that have already been set aside for that purpose. Moreover, researchers can provide modest but still meaningful opportunities for community members to earn money, learn research skills, and empower themselves through participating in research. Finally, the argument can be made that research is needed in communities such as Masidaal precisely because they are unstable, in crisis, and require health care solutions grounded in an understanding of their unstable and challenging characteristics. For these reasons, we support the need to conduct research in communities such as Masidaal, as well as the need to take into account how community need and crisis may affect the ethics of conducting local research.

How should we be conducting our research?

Apart from our role as researchers, at least two factors importantly affected the degree of local relevance or connectedness of our research: (1) our plan to address a single disease, cervical cancer, rather than multiple and interconnected sources of health and suffering, and, (2) exposure of this plan to the community for scrutiny, feedback, and reshaping.

The first of these factors reflects the extent to which our research—and community-based health research generally—is rooted in Western scientific knowledge and disease models. The community of Masidaal challenged this dominance by appealing for a focus on cervical health rather than cervical cancer, and by pointing to the social, economic, and environmental determinants of suffering, and not just physical and behavioral determinants.

The second of these factors reflects our commitment to a participatory research process. Notably, our approach differed from other participatory approaches in that we did not “start[ ] with the other’s agenda” (Pestronk, 2000), or, “place[ ] subjects in the driving seat” of the research process (Minkler, 2004). However, we did provide multiple opportunities for the community to meet with us, critically comment and discuss our research plans, and point to its broader social, economic, and other needs and concerns. We also involved the community directly in the research process by training community members to conduct and help analyze the focus group discussions. In other words, we aimed to partner with the community on a number of levels, and, in so doing, to strip away the “veil of positivist objectivity” (Speed, 2006) that accompanies most nonparticipatory research.

A key outcome of our version of community engagement was the recommendation that we adopt the concept of cervical health. The concept appealed to us because it represented a middle point between our narrowly fashioned focus on cervical cancer and the community’s interest in a far wider-ranging set of concerns and issues. We would argue that the adoption of the concept of cervical health has had the effect of enhancing the relevance of our research to the community, in that it amounts to a demonstration of our willingness to acknowledge the broader problems and interconnections affecting women’s health in Masidaal and South Africa generally. The concept is also not too broad as to throw into question (for our sponsors and other stakeholders) the relevance of our research to cervical cancer and cancer prevention and control generally. Thus, the adoption of community or “insider” concepts such as cervical health can be viewed as a key step in the promotion of mutual, as well as local, relevancy of research. However, such steps do not totally resolve the complex issue of research relevancy.

For one, our adoption of the concept of cervical health does not change the fact that our research and intervention will likely still take years to complete. It may even take longer now that we have adopted the concept of cervical health, which may require us to consider new and additional variables, research questions, and hypotheses in an effort to understand and operationalize the concept. Also, it is unclear in what direction, exactly, the concept of cervical health will take our research.

One possibility is to explore the link between cervical cancer and other women’s health and social issues, such as sexual abuse and violence. This was a major concern among our focus group participants, and calls to mind recent studies suggesting that a woman’s history of physical and sexual abuse is linked to her cervical health, with women less likely to seek cervical screening if they have suffered physical or sexual abuse (Farley, Golding, & Minkoff, 2002; Harsanyi, Mott, Kendall, & Blight, 2003). Building our research on this connection may be an additional way of enhancing the local relevance and responsiveness of the research. It may also give concrete meaning to the concept of cervical health, as a condition dependent on the health of gender relations and sexual attitudes, among other things.

Future challenges facing our research

Changing direction in a research study to reflect a community’s interests and concerns may alleviate some problems of relevancy, while engendering others. In our case, a shift toward studying cervical health, sexuality, and violence may engender many of the ethical and other problems associated with studies of sexuality and violence more generally (Lee & Stanko, 2003).

Our previous efforts to meet with and engage community leaders, women’s interest groups, schools, parents, children, and others in the community may help in negotiating these new challenges. Similarly, our CAB could be used to facilitate community-based discussion, debate, and feedback on the inclusion of issues of sexuality and violence in our research.

Another ongoing challenge will be to address, at some level, the community’s immediate need for resources and services, which our reshaped research still will not have done. For this reason, we have started disseminating our key focus group findings to various stakeholders with the formal capacity to alleviate some of Masidaal’s resource problems, including local government, regional NGOs, and South Africa’s Minister of Health, to whom we have sent a full report outlining people’s concerns and needs. We have also initiated discussions at the community level, for example, with school administrators, student representative bodies, and parents, in order to talk about our focus group findings on the problems confronting youth in the schools and the community at large.

These findings surprised few people; however, we heard many people comment that they had not been previously aware that others in the community—including children and youth—entertained the same concerns and viewpoints as they did on youthful crime and violence, alcohol and substance abuse, unprotected sex, and other issues. Having enabled this recognition indicates that we have a key role to play in promoting dialogue, mutual respect, and possible collaboration among different sectors of the community. Notably, this is a role that we can adopt in addition to our role as researchers, with little need for additional time and funds, and with the goal of enhancing the relevancy of our overall presence in the community, and not just our research activities.

Finally, a different but equally important set of challenges awaiting our attention includes the sustainability of our CAB, the meaning of “community” in Masidaal, and, the retention of research participants and project personnel, among other issues. These issues will need to be carefully considered and, better yet, discussed with local stakeholders, who may have creative suggestions for negotiating the unstable and unpredictable aspects of life in Masidaal.

Conclusion

Our goal in this paper has been to explore some of the ethical challenges facing the design and conduct of locally relevant and appropriate international health research. International health research is critically important to help dismantle the 10/90 gap and improve the health and wellbeing of people worldwide. However, as we have tried to illustrate, the relevancy of international health research to local communities and individuals is complex, shifting, and hard to achieve. The act of conducting research and defining oneself as a researcher, of focusing on diseases as opposed to health or multiple sources of suffering, and of inviting communities to critique and reshape the research but not to define its original purpose, can significantly diminish a research initiative’s local relevance and appropriateness.

We have attempted to acknowledge these challenges by adopting the concept of cervical health, by keeping our research design open and flexible, by inviting community members to participate in our research, and by creating opportunities for community-based data dissemination and further dialogue in the community. International health research committed to providing these kinds of opportunities is less likely to be so narrowly formulated as to be isolated from a community’s broader problems, and of dubious local relevance as a result.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the community members who helped us develop, implement and analyze the results of the focus groups, as well as provide invaluable insights and guidance. Given confidentiality concerns, we list them here only by their first names: Berlina, Doline, Charlene, Enrico, Fairuz, Julie, Liezel, Lungile, Luthando, Nomfundo, Patsy, Susan, Vuyokazi, and Wendy. We would also like to thank our US-based research staff for their assistance, including Mara Buchbinder, Michelle Nebergall, and Sarah Schramm. This research was supported by the R25 Fellowship Program and the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center at University Hospitals/Case Western Reserve University.

Footnotes

Masidaal is a pseudonym, which we use to help protect the identities of those who live there.

A product of apartheid that is today still widely used in South Africa, the term “Coloured” refers to people of mixed race, most of whom reside in the Cape.

References

- Benatar S. Reflections and recommendations on research ethics in developing countries. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;54:1131–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta Z. Ethics in international health research: A perspective from the developing world. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2002;80:114–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C. “Letting them die”: Why HIV/AIDS prevention programmes fail. Indiana University Press; Bloomington, IN: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, MacPhail C. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:331–345. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua A, Ford N, Wilson D, Cawthorne P. The Tenofovir pre-exposure prophylaxis trial in Thailand: Researchers should show more openness in their engagement with the community. PLoS Medicine. 2005:e346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey S. The 10/90 report on health research 2003– 2004. Global Health Forum for Health Research; Geneva, Switzerland: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health South Africa . National guideline on cervical cancer screening program. Department of Health South Africa; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Killen J, Grady C. What makes clinical research in developing countries ethical? The benchmarks of ethical research. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;189:932–937. doi: 10.1086/381709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley M, Golding JM, Minkoff JR. Is a history of trauma associated with a reduced likelihood of cervical cancer screening? Journal of Family Practice. 2002;51(10):827–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsanyi A, Mott S, Kendall S, Blight A. The impact of a history of child sexual assault on women’s decisions and experiences of cervical screening. Australian Family Physician. 2003;32(9):761–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Stanko EA. Researching violence: Essays on methodology and measurement. Routledge; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Macklin R. After Helsinki: Unresolved issues in international research. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal. 2004a;11(1):17–36. doi: 10.1353/ken.2001.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklin R. Double standards in medical research in developing countries. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2004b. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall P. Human rights, cultural pluralism, and international health research. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics. 2005;26(6):529–557. doi: 10.1007/s11017-005-2199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(6):684–697. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community-based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2003. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Motteux N, Binns T, Nel E, Rowntree K. Empowerment for development: Taking participatory appraisal further in rural South Africa. Development in Practice. 1999;9(3):261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Pestronk RM. Community-based practice in public health. In: Bruce TA, McKane SU, editors. Community-based public health: A partnership model. American Public Health Association; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Mills E. The abandoned trials of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV: What went wrong? PLoS Medicine. 2005:e234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed S. At the crossroads of human rights and anthropology: Toward a critically engaged activist research. American Anthropologist. 2006;108(1):67–76. [Google Scholar]

- The National Health Laboratory Service 1997 National cancer registry: The cancer association of South Africa. 1997.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group . US cancer statistics: 2002 incidence and mortality. US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, MacPhail C, Campbell C, Taljaard D, Gouws E, Moema S, et al. The Carletonville-Mothusimpilo project: Limiting transmission of HIV through community-based interventions. South Africa Journal of Science. 2000;96:351–359. [Google Scholar]