Abstract

Backgroud

It has been shown that different symptoms or symptom combinations of neuropathic pain (NeP) may correspond to different mechanistic backgrounds and respond differently to treatment. The Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI) is able to detect distinct clusters of symptoms (i.e. dimensions) with a putative common mechanistic background. The present study described the psychometric validation of the Portuguese version (PV) of the NPSI.

Methods

Patients were seen in two consecutive visits, three to four weeks apart. They were asked to: (i) rate their mean pain intensity in the last 24 hours on an 11-point (0-10) numerical scale; (ii) complete the PV-NPSI; (iii) provide the list of pain medications and doses currently in use. VAS and Global Impression of Change (GIC) were filled out in the second visit.

Results

PV-NPSI underwent test-retest reliability, factor analysis, analysis of sensitivity to changes between both visits. The PV-NPSI was reliable in this setting, with a good intra-class correlation for all items. The factorial analysis showed that the PV-NPSI inventory assessed different components of neuropathic pain. Five different factors were found. The PV-NPSI was adequate to evaluate patients with neuropathic pain and to detect clusters of NeP symptoms.

Conclusions

The psychometric properties of the PV-NPSI rendered it adequate to evaluate patients with both central and peripheral neuropathic pain syndromes and to detect clusters of NeP symptoms.

Keywords: Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory, Portuguese language, neuropathic pain, pain assessment, questionnaire

Introduction

Neuropathic pain (NeP) probably concerns 7-8% of the general population [1,2]. In addition to a number of patients with various neurological diseases [3], NeP affects significant proportions of patients with diabetes [4], low back pain [5], post-surgical pain [6], cancer [7,8] and some infectious diseases [9] and has a major impact on quality of life.

Neuropathic pain syndromes are rather heterogeneous and the relationship between a certain etiology and the symptoms reported by patients are not straightforward. Different symptoms (i.e., allodynia, burning or paroxysmal pain) may coexist in the same patient and may reflect different mechanisms of disease [10]. Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been shown that different symptoms or symptom combinations may respond differently to treatment [11-13]. These data highlight the importance of a specific measurement of neuropathic pain symptoms or neuropathic components, to assess the effects of treatment both in clinical trials and in daily practice.

Only two questionnaires have been specifically developed to assess the effects of treatment in neuropathic pain syndromes [14,15]. To date, the only tool that has been validated in neuropathic pain syndromes of both central and peripheral origins is the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI). Also, it is the sole that has underwent factorial analysis confirming that the qualities of the symptoms measured by this inventory reflect distinct clusters of symptoms (i.e. dimensions) with a putative common mechanistic background [10,15].

Here we validated the translated Portuguese version of the NPSI (PV-NPSI) [16]. Portuguese is spoken by 240 million people and in the main language in more than ten countries in America, Europe, Africa and Asia [17]. So far, the NPSI has been translated into more than 60 languages, but its multidimensional structure has only been confirmed into Italian [18] and Spanish [19].

Methods

After translation of the NPSI from the original French version and verification of its cultural and conceptual adequacy in Brazilian patients [16], the psychometric validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the NPSI was performed in one hundred consecutive patients with neuropathic pain seen in our outpatient pain clinic from January to July 2009. The study was approved by our I nstitution's Ethics Review Board (Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Patients

Inclusion criteria were men and women with chronic (> 3 months) neuropathic pain of moderate to severe intensity (> 30 mm on a 100 mm visual analog scale) of either central or peripheral origin. Neuropathic pain was diagnosed based on the presence of pain with neuropathic characteristics in the topographic distribution of a nervous structure [20]. Lesion or disease to the somatosensory system was confirmed by nerve conduction tests, magnetic resonance imaging and blood tests when indicated. Exclusion criteria were: the presence of major depression, alcohol abuse as assessed by the CAGE questionnaire [21], the presence of an other pain of clear non neuropathic origins (e.g. myofascial pain syndrome) [22], instances where the lesion to the somatosensory system could no be clearly detected (complex regional pain syndrome) [23] and pain syndromes of clear mixed origins (failed back surgery syndrome, tumor-related pain), low level of education (less than eight years) and non Portuguese-native speakers.

Study Design

Patients were seen in two consecutive visits, three to four weeks apart. In the first visit, before the regular consultation, they were invited to participate in the study protocol and gave their informed consent. Name, age, neuropathic pain diagnosis and associated disorders were recorded, as well as pain symptoms duration. Then they were asked to: (i) rate their mean pain intensity in the last 24 hours on an 11-point (0-10) numerical scale; (ii) complete the PV-NPSI; (iii) provide the list of pain medications and doses currently in use. Pain medication and dosing were quantified according to the Medication Quantification Score (MQS) [24]. In the second visit, patients were asked to rate the intensity of their pain on an 11-point scale, to fill out the PV-NPSI and to rate the global evolution of their pain since the first visit by the Patient Global Impression of Change (p-GIC). The evaluator also rated the global evolution of the pain by the Clinical Global Impression of Change (c-GIC). In both cases, the GIC included seven ranks ranging from 1 to 7 (1 = very much improved, 2 = moderately improved, 3 = slightly improved, 4 = no change; 5 = slightly aggravated; 6 = moderately aggravated; 7 = very much aggravated). The number of patients included in the study was calculated from the total number of items of the PV-NPSI that would undergo factorial analyses [25] and from the original NPSI publication [15].

Assessment of the psychometrics properties of the PV-NPSI

Assessment of test-retest reliability

The test-retest reliability of each item and the score of the PV-NPSI was assessed using the Intraclass coefficient (ICC) calculated by the estimation of components by analysis of variance [26]. Long-term reliability was evaluated by comparing the PV-NPSI scores and sub scores in patients who did not show any change in their pain during both visits (i.e: score 4 - no change; on the p-CGC in the second visit).

Factor Analysis

An exploratory factor analysis was performed using the principal component analysis as the method of extraction. The Catell Scree test was used for determining the number of factors extracted. Independent factors were obtained using the Varimax rotation method.

Convergent validity

Correlations between changes in pain intensity on the 11-point numeric scale and the changes in the PV-NPSI total score and sub scores were evaluated by the Spearman's correlation coefficient.

Analysis of sensitivity to changes between both visits

The correlation between the subjective evaluation by patients (p-GIC) in the second visit and the change in the PV-NPSI score and sub scores were assessed by the Spearman's Correlation Coefficient.

Results

Clinical features

Ninety-four patients were included in the study. Six failed to come to the second visit within the study interval due to personal reasons. Patient's clinical characteristics and pain etiology are expressed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main clinical characteristics of patients included in the study.

| Clinical and demographic data | |

|---|---|

| Age | 52.6 ± 14.9 (27-84) |

| Sex (women/men) | 37/57 |

| Mean duration of pain (months) | 51.7 ± 21.4 (6-120) |

| Mean pain intensity (VAS) | 6.7 ± 2.0 (4-10) |

| Mean MQS | 10.1 ± 5.3 (1.0-25.0) |

| Aetiology of neuropathic pain | |

| Nerve trauma | 15 (15.9%) |

| Post herpetic neuralgia | 20 (21.3%) |

| Diabetic polyneuropathy | 6 (6.4%) |

| Non-diabetic polyneuropathy | 5 (5.3%) |

| Post-stroke pain | 4 (4.2%) |

| Spinal cord trauma | 9 (9.5%) |

| Plexus avulsion | 19 (20.2%) |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | 4 (4.25%) |

| Syringomyelia | 2 (2.1%) |

| Leprosy associated neuropathic pain | 10 (10.6%) |

| Medication use | |

| Medication Quantification Score | 10.14 ± 5.96 |

Results are expressed in average ± standard deviation (range).

Face validity

The PV-NPSI was filled out in less than 8 minutes by 85% of the patients. It took less than 12 minutes in the remaining. The "prevalence" (i.e. percentage of patients reporting a score > 0) in the majority of items was 65% (table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of items reported as > 1.

| Pain Descriptor (items) | Percentage of patients who reported a score > 0 |

|---|---|

| Burning | 73.4% |

| Squeezing | 57.4% |

| Pressure | 56.3% |

| Electric shocks (5) | 65.9% |

| Stabbing | 47.9% |

| Evoked by brushing | 64.8% |

| Evoked by pressure (8) | 60.6% |

| Evoked by cold stimulus | 63.8% |

| Pins and needles | 68.0% |

| Tingling | 81.9% |

Test-retest validity

Thirty patients did not present any change in their pain between both visits (ie. p-GIC). The NPSI scores of these patients were retained to evaluate the test-retest reliability of the PV-NPSI (table 3).

Table 3.

Interclass Correlation Coefficient between of each PV-NPSI item in both visits.

| Test-retest reliability | |

|---|---|

| Burning | 0.9294 |

| Pressure | 0.9450 |

| Squeezing | 0.9664 |

| Electric shocks | 0.9309 |

| Stabbing | 0.9365 |

| Pain evoked by brushing | 0.6633 |

| Pin evoked by pressure | 0.7844 |

| Pain evoked by cold stimuli | 0.7820 |

| Pins and needles | 0.7596 |

| Tingling | 0.6280 |

| Total Score | 0.7678 |

Factor analysis

The factor analysis identified a five-factor solution, which accounted for 71% of the total variance. Most items had high loadings on only one factor (Table 4).

Table 4.

Rotated factor loadings and communalities: Varimax Rotation.

| Variable | Factor1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Communality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | -0.083 | 0.032 | 0.037 | -0.929 | 0.050 | 0.875 |

| Q2 | 0.538 | -0.165 | -0.510 | -0.369 | 0.061 | 0.716 |

| Q3 | 0.607 | 0.226 | -0.427 | 0.091 | -0.370 | 0.747 |

| Q5 | 0.229 | 0.145 | -0.200 | -0.066 | 0.831 | 0.809 |

| Q6 | 0.324 | 0.774 | 0.048 | -0.108 | -0.042 | 0.721 |

| Q8 | 0.776 | 0.095 | 0.155 | -0.123 | 0.166 | 0.678 |

| Q9 | 0.589 | 0.337 | -0.101 | 0.128 | 0.049 | 0.489 |

| Q10 | 0.651 | 0.132 | 0.037 | 0.283 | 0.333 | 0.634 |

| Q11 | 0.032 | 0.759 | -0.199 | 0.073 | 0.191 | 0.658 |

| Q12 | -0.096 | 0.163 | -0.837 | 0.071 | 0.178 | 0.773 |

| Variance | 2.2054 | 1.4420 | 1.2622 | 1.1451 | 1.0447 | 7.0994 |

| % Var | 0.221 | 0.144 | 0.126 | 0.115 | 0.104 | 0.710 |

| Factor 1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | |

| Factor 2 | Q6 | Q11 | ||||

| Factor 3 | Q12 | |||||

| Factor 4 | Q1 | |||||

| Factor 5 | Q5 | |||||

Each of the five factors corresponded to a relevant clinical component of neuropathic pain. Factor 1 included the three items related to evoked pain (i.e. pain evoked by brushing, pressure or contact with cold) and two spontaneous pain items (squeezing and pressure). Factor 2 included two items (i.e. stabbing and pins and needles), which might correspond to the paroxysmal component of spontaneous pain. Factor 3 included tingling (corresponding to the abnormal sensations). Factor 4 included one item (burning) corresponding to superficial component of ongoing pain frequently observed in neuropathic pain syndromes. Finally, factor 5 included only one item (electric shocks) corresponded to clear paroxysmal pain.

Convergent analysis

The total score of the questionnaire (1st and 2nd visits) correlated with the numerical rating scale measured in each visit (Spearman correlation = 0.40; p < 0.0001; and 0.53; p < 0.0001; respectively). However, the change in the PV-NPSI score between both visits (PV-NPSI visit 2 - PV-NPSI visit 1) only weakly correlated with the change in the visual numeric scale between both visits (2nd score - 1st score) (Spearman correlation = 0.22). The change in the PV-NPSI score between both visits did not significantly correlate with pain duration or medication use (MQS).

Sensitivity to change

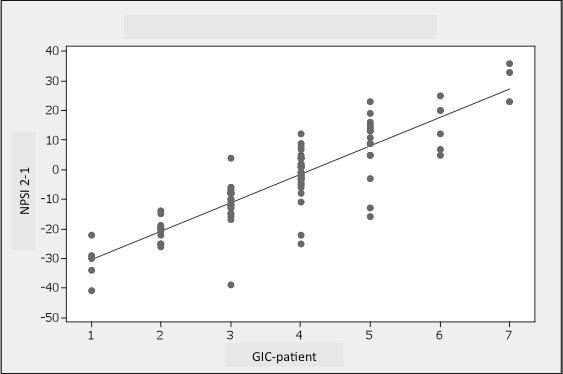

The p-GIC and c-GIC scores at the second visit strongly correlated (rho = 0.727; rho = 0.645, respectively) with the change in the PV-NPSI score between the two visits (PV-NPSI visit 2 - PV-NPSI visit 1) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation between the GIC-p scores at the second visit and the change in the PV-NPSI score between the two visits (PV-NPSI visit 2 - PV-NPSI visit 1) (rho = 0.727).

The p-GIC and c-GIC scores at the second visit moderately correlated (rho = 0.446, 0.440) with the change in the visual numeric scale score between both visits (VNS from 2nd visit - VNS from 1st visit).

Discussion

Neuropathic pain is common [27], and its prevalence in certain populations of patients is particularly high, such as in diabetics, cancer, and HIV patients [8,28]. Different screening tools have been proposed to identify patients with a higher probability to present neuropathic pain, such as the LANSS [29,30] and the DN-4 [2]. These tools have been translated and validated in different languages and are used broadly in clinical trials and epidemiological studies [7,31]. Only two scales were specifically created and validated to assess neuropathic pain syndromes [14,15]. The NPSI is the only tool validated in patients with neuropathic pain of central and peripheral origin and has a factorial design validated in a broad range neuropathic pain patients.

The present study described the psychometric validation of the Portuguese version of the NPSI. The validation process showed that the present version of the self-questionnaire is: (i) valid and reliable; (ii) it is sensitive to changes in neuropathic pain of both central and peripheral origin; and (iii) it assessed different aspects of neuropathic pain.

The PV-NPSI was filled out in a relatively short period of time making it suitable for the use in clinical practice and in clinical studies. All descriptors were reported in a significant frequency of patients, with a prevalence of 65%. We assessed the test-retest validity of the inventory in those patients who did not present any change in their pain intensity between both visits. The PV-NPSI was reliable in this setting, with a good intraclass correlation for all items.

The total score of the PV-NPSI in the 1st and 2nd visits correlated with the visual numeric scale score in each of these sessions. However, the change in the PV-NPSI from the 2nd to the 1st visit only weakly correlated to the changes in the VNS score between both instances. This is similar to what was found in the original version of the NPSI [15]. Interestingly, GIC scores in the second visit showed a high correlation with the change in the PV-NPSI between both visits, while the change in the VNS score only moderately correlated with the GIC scores. This attests that in this population of neuropathic pain patients, the total score of the PV-NPSI was better suited to assess neuropathic pain characteristics than the VNS score, showing good validity and reliability.

The factorial analysis showed that the PV-NPSI assessed different components of neuropathic pain. Five different factors were found. The first factor included evoked pain (i.e. pain evoked by brushing, pressure or contact with cold) and two spontaneous pain descriptors (squeezing and pressure). Two paroxysmal descriptors (stabbing and pins and needles) were clustered in a second factor. The three remaining descriptors were grouped in one factor each (burning pain, electric shocks and tingling). Some of the cluster patterns were slightly different from the original version where spontaneous pain and paroxysmal descriptors were clustered in a single factor each. These differences probably reflect different valences of each descriptor between the two populations [15].

Neuropathic pain is a rather heterogeneous entity and different symptoms may be caused by a single etiological factor, thus suggesting it is a "trans-etiological" entity [10]. Neuropathic pain symptoms are thought to reflect specific pain mechanisms. Two main approaches have employed questionnaires based on pain characteristics to broaden our knowledge on this topic. One used these tools to gain mechanistic insights on this pain syndrome. For example, it has been shown that the intensity of ongoing pain, as detected by the NPSI inversely correlated to the amplitude of laser evoked potentials in patients with painful distal polyneuropathy, suggesting that damage to intra-epidermal nociceptive terminals would be implicated in this specific symptom of NeP [32]. In another study, it has been shown that patients presenting exclusively with spontaneous pain according to the NPSI significantly differed from those also presenting with evoked pain. Isolated spontaneous pain was highly correlated with a greater decrease in white matter tract metrics seen under tractography, suggesting a more intense injury to the somatosensory system. Also, the presence of evoked pain in the NPSI was associated with a more discrete spinothalamic dysfunction as assessed by laser-evoked potentials when compared to patients without this pain symptom [33]. This supports the idea that different aspects of neuropathic pain as assessed by the NPSI are associated with different anatomical dysfunctions and pathophysiological backgrounds in patients with NeP. Another use of these tools was to to guide mechanism-based approaches to NeP treatment, since it has been increasingly shown that the efficacy of pharmacological treatment may vary depending on the presence of certain symptoms (mechanisms) of neuropathic pain [12,34,35].

In conclusion, the psychometric properties of the PV-NPSI render it adequate to evaluate patients with both central and peripheral neuropathic pain syndromes. The reliability of the different descriptors was adequate and sensitive to change and the NPSI may help select subgroups of NeP patients with different anatomical and mechanistic dysfunctions, and possibly different response to treatment.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Study Design: DCA, DB, MJT. Data Collection: CMN, AFB, LTY, JA, PRNS, HelenaHK, KS. Data bank feeding: TZ, RG. Statistical analyses: DCA, ETF. Manuscript writing: DCA, KASLF. Manuscript revising: DB, MJT. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Daniel Ciampi de Andrade, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Karine ASL Ferreira, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Carine M Nishimura, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Lyn T Yeng, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Abrahão F Batista, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Katia de Sá, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Joaci Araujo, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Patrick RNAG Stump, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Helena H Kaziyama, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Ricardo Galhardoni, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Erich T Fonoff, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Gerson Ballester, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Telma Zakka, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Didier Bouhassira, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

Manoel J Teixeira, Email: ciampi@usp.br.

References

- Bennett M. The LANSS Pain Scale: the Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain. 2001;92(1-2):147–157. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhassira D, Lanteri-Minet M, Attal N, Laurent B, Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136(3):380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V, Fletcher D, Martin F, Orlikowski D, Sharshar T, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D, Attal N. Small fibre impairment predicts neuropathic pain in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Pain. 2010;151(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Friedman M, Bonzo D, Richards P. The validity of the neuropathic pain scale for assessing diabetic neuropathic pain in a clinical trial. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(1):97–103. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000173018.64741.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaki AM, El-Yaski AZ, Youseif E. Identifying neuropathic pain among patients with chronic low-back pain: use of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs pain scale. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30(5):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V, Fletcher D, Bouhassira D, Sessler DI, Chauvin M. The evolution of primary hyperalgesia in orthopedic surgery: quantitative sensory testing and clinical evaluation before and after total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2007;105(3):815–821. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000278091.29062.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerba M, Wu JS, Duan Q, Hagen NA, Bennett MI. Neuropathic Pain Features in Patients With Bone Metastases Referred for Palliative Radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Attal N, Bouhassira D, Gautron M, Vaillant JN, Mitry E, Lepere C, Rougier P, Guirimand F. Thermal hyperalgesia as a marker of oxaliplatin neurotoxicity: a prospective quantified sensory assessment study. Pain. 2009;144(3):245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade DC, Jean S, Clavelou P, Dallel R, Bouhassira D. Chronic pain associated with the Chikungunya Fever: long lasting burden of an acute illness. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attal N, Fermanian C, Fermanian J, Lanteri-Minet M, Alchaar H, Bouhassira D. Neuropathic pain: are there distinct subtypes depending on the aetiology or anatomical lesion? Pain. 2008;138(2):343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attal N, Guirimand F, Brasseur L, Gaude V, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D. Effects of IV morphine in central pain: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Neurology. 2002;58(4):554–563. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attal N, Gaude V, Brasseur L, Dupuy M, Guirimand F, Parker F, Bouhassira D. Intravenous lidocaine in central pain: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, psychophysical study. Neurology. 2000;54(3):564–574. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attal N, Brasseur L, Parker F, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D. Effects of gabapentin on the different components of peripheral and central neuropathic pain syndromes: a pilot study. Eur Neurol. 1998;40(4):191–200. doi: 10.1159/000007979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galer BS, Jensen MP. Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: the Neuropathic Pain Scale. Neurology. 1997;48(2):332–338. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhassira D, Attal N, Fermanian J, Alchaar H, Gautron M, Masquelier E, Rostaing S, Lanteri-Minet M, Collin E, Grisart J. et al. Development and validation of the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory. Pain. 2004;108(3):248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford B, Bouhassira D, Wong A, Dukes E. Conceptual adequacy of the neuropathic pain symptom inventory in six countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:62. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RG. , Jr. Portuguese. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 15. Vol. 1. SIL International; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Padua L, Briani C, Jann S, Nobile-Orazio E, Pazzaglia C, Morini A, Mondelli M, Ciaramitaro P, Cavaletti G, Cocito D. et al. Validation of the Italian version of the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory in peripheral nervous system diseases. Neurol Sci. 2009;30(2):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s10072-009-0025-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villoria J, Rodríguez M, Berro MJ, Stern A, Sánchez-Magro I. Psychometric Validation of the neuropathic pain symptom inventory for its use in Spanish. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(1):134–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, Hansson P, Hughes R, Nurmikko T, Serra J. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008;70(18):1630–1635. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000282763.29778.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.1984.03350140051025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons DG. Review of enigmatic MTrPs as a common cause of enigmatic musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2004;14(1):95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justins DM. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Seattle: IASP Scientific Program Committee (11th World Congress on Pain); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Masters Steedman S, Middaugh SJ, Kee WG, Carson DS, Harden RN, Miller MC. Chronic-pain medications: equivalence levels and method of quantifying usage. Clin J Pain. 1992;8(3):204–214. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachigan SK. Multivariate statistical analysis: a conceptual introduction. 2. New york: Radius Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Muller R, Buttner P. A critical discussion of intraclass correlation coefficients. Stat Med. 1994;13(23-24):2465–2476. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780132310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrance N, Smith BH, Bennett MI, Lee AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population survey. J Pain. 2006;7(4):281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter J, Higginson IJ, Scadding JW, Quigley C. Identifying neuropathic pain in patients with head and neck cancer: use of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs Scale. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(8):379–383. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.8.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C, Galvez R, Insausti J, Bennett M, Ruiz M, Rejas J. [Linguistic adaptation and Spanish validation of the LANSS (Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs) scale for the diagnosis of neuropathic pain] Med Clin (Barc) 2006;127(13):485–491. doi: 10.1157/13093266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yucel A, Senocak M, Kocasoy Orhan E, Cimen A, Ertas M. Results of the Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs pain scale in Turkey: a validation study. J Pain. 2004;5(8):427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos JG, Brito JO, Andrade DCd, Kaziyama VM, Ferreira KA, Souza I, Teixeira MJ, Bouhassira D, Baptista AF. Translation to Portuguese and Validation of the Douleur Neuropathique 4 Questionnaire. The Journal of Pain. 2010;11(5):484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truini A, Biasiotta A, La Cesa S, Di Stefano G, Galeotti F, Petrucci MT, Inghilleri M, Cartoni C, Pergolini M, Cruccu G. Mechanisms of pain in distal symmetric polyneuropathy: a combined clinical and neurophysiological study. Pain. 2010;150(3):516–521. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatem SM, Attal N, Ducreux D, Gautron M, Parker F, Plaghki L, Bouhassira D. Clinical, functional and structural determinants of central pain in syringomyelia. Brain. 2010;133(11):3409–3422. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E, Midbari A, Haddad M, Pud D. Predicting the analgesic effect to oxycodone by 'static' and 'dynamic' quantitative sensory testing in healthy subjects. Pain. 2010;151(1):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Bach FW, Johannesen IL, Jensen TS. Lamotrigine in spinal cord injury pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2002;96(3):375–383. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]