Abstract

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) are valuable tools as biochemical markers for studying cellular processes. Red fluorescent proteins (RFPs) are highly desirable for in vivo applications because they absorb and emit light in the red region of the spectrum where cellular autofluorescence is low. The naturally occurring fluorescent proteins with emission peaks in this region of the spectrum occur in dimeric or tetrameric forms. The development of mutant monomeric variants of RFPs has resulted in several novel FPs known as mFruits. Though oxygen is required for maturation of the chromophore, it is known that photobleaching of FPs is oxygen sensitive, and oxygen-free conditions result in improved photostabilities. Therefore, understanding oxygen diffusion pathways in FPs is important for both photostabilites and maturation of the chromophores. In this paper, we use molecular dynamics calculations to investigate the protein barrel fluctuations in mCherry, which is one of the most useful monomeric mFruit variant. We employ implicit ligand sampling to determine oxygen pathways from the bulk solvent into the mCherry chromophore in the interior of the protein. We also show that these pathways can be blocked or altered and barrel fluctuations can be reduced by strategic amino acid substitutions.

INTRODUCTION

Fluorescent proteins (FPs) are valuable tools in molecular and cell biology and are used as biochemical markers for studying cellular processes.1, 2, 3 Red fluorescent proteins (RFPs) are highly desirable for in vivo applications because they absorb and emit light in the red region of the spectrum where cellular autofluorescence is low.4 However, the naturally occurring fluorescent proteins with emission peaks in this region of the spectrum occur in dimeric or tetrameric forms,5, 6 which tend to oligomerize7, 8 and render them unsuitable for fusion tagging.9 The development of mutant monomeric variants of RFPs to avoid these issues has resulted in several novel monomeric FPs known as mFruits.10 Some of the most promising mFruits are mCherry, mOrange, and mStrawberry11 and their names reflect the wavelengths of their corresponding emission spectra.

Though oxygen is required for maturation of the chromophore, it is known that photobleaching of FPs is oxygen sensitive, and oxygen-free conditions result in improved photostabilities.12 This poses limitations to the next generation of single-molecule spectroscopy and low-copy fluorescence microscopy experiments and therefore, improving the photostability of the mFruits is highly desirable. The photobleaching of the monomeric variants of RFPs has been attributed to the lack of proper shielding against oxygen or other molecules by the beta barrel surface.7 Increasing evidence suggests that protein flexibility plays a major role in gas access into many proteins13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and the dynamic fluctuations in the size of transient cavities due to residues’ thermal fluctuations are the determining factor in the pathways of gas diffusion.19, 20, 21, 22 Oxygen diffusion in myoglobin's distal pocket has been extensively studied, both experimentally and by simulations, in light of the influence of different protein conformations or mutations.14, 23 In FPs, the interaction between the chromophore and the surrounding protein has important implications for both structures.24 The electronic molecular orbitals of the chromophore that are responsible for its spectral properties may be modified by the surrounding protein. Also, protein barrel fluctuations and the motion of residues can affect the spectral properties and the lifetime of the fluorescence.25

Recent developments in efficient computational sampling methods have allowed thorough scanning of the possible pathways for gas diffusion in the interior of proteins.26, 27, 28, 29 For example, such computational investigations have proved useful in understanding gas diffusion in many protein systems such as molecular dioxygen pathways via dynamic oxygen access channels in flavoproteins,30, 31, 32 ammonia transport in carbamoyl phosphate synthetase,33, 34, 35 and gas diffusion and channeling in hemoglobin.28, 36 In this paper, we use explicit solvent all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate the protein barrel fluctuations in mCherry, which is one of the most useful monomeric variants of RFP. We compare the barrel fluctuations in mCherry to those in citrine, a yellow variant (YFP) of green fluorescent protein (GFP). Although citrine and mCherry belong to different FP families and the photobleaching mechanisms can be different, we compare the barrel structural integrity of these proteins due to two main reasons. First, citrine is a natural monomer and a GFP homologue of mCherry with a similar barrel structure and second, it is the most useful FP among all YFPs due to its reduced halide sensitivity and improved photstability.37, 38 Other YFPs are very sensitive to halides due to easy ion access via a solvent channel or cavity formed close to the dimer interface.39, 40 In citrine, this cavity is filled by a mutation Gln69Met preventing the access to the ion.37 A similar effect is desired in mCherry. We employ implicit ligand sampling (ILS) to determine oxygen pathways from the bulk solvent into the mCherry active site. Using these results as a guide, we show that the barrel fluctuations and the oxygen pathways can be altered or blocked with strategic amino acid substitutions.

Following the folding of the protein, the chromophore formation involves cyclization of tripeptide and oxidation, which requires molecular oxygen.41 Therefore, the maturation times can depend on the accessibility of molecular oxygen. For example, it is shown that a water-filled pore was essential for fast maturation of TurboGFP chromophore.42 The pore that leads from outside of the barrel to the inside chromophore possibly facilitates molecular oxygen entry. Upon comparing the crystal structures of GFPs and mFruits, structural differences in the beta barrels are observed. The tetramer subunit interactions present in the naturally occurring red fluorescent protein DsRed are not present in the mFruit monomeric forms and therefore the latter is expected to have less structural integrity. The crystal structures show larger openings in the mFruits’ protein structure, which may be transiently increased further by more pronounced thermal fluctuations. These larger openings may allow oxygen to pass more easily to the chromophore which may have implications to both chromophore maturation speed as well as photobleaching due to oxidation.

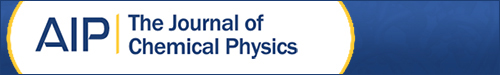

Figure 1a is a superposition of ribbon structures of the RFP mCherry (PDB code 2H5Q) and its GFP homologue citrine (PDB code 1HUY). Figure 1b displays a space-filling model of the β7-β10 region and shows that the gap between β7 and β10 is smaller in citrine. We show that differences in this region create pathways in mCherry for dioxygen diffusion through the barrel to the chromophore.

Figure 1.

(a) Superposition of ribbon structures of red (mCherry) and yellow (citrine) fluorescent proteins. (b) The β7-β10 region is displayed with a space filling model which shows that the gap in mCherry is larger than in citrine.

METHODS

Molecular dynamics computations

The time series trajectories were obtained from explicit solvent, all-atom simulations using the CHARMM27 force field.43 The initial x-ray crystallographic structures of RFP mCherry (pdb code 2H5Q) and YFP citrine (pdb code 1HUY) have a few missing amino acid residues. The missing amino acid residues were completed using MODELLER.44 For the chromophore representation, we used pre-cyclized forms that are composed of three amino acids each, Met66-Tyr67-Gly68 for mCherry and Gly65-Tyr66-Gly67 for citrine. Although the fluorescent spectral properties are only possible in mature chromophores, the simpler representative forms of chromophores can be used for the purpose of investigating the barrel fluctuations.45

The MMTSB toolset46 was used to set up the system for simulations. The initial structures of mCherry and citrine were separately solvated in octahedral boxes under periodic boundary conditions with TIP3P water molecules with a box cut-off of 10 Å. For mCherry, 11 319 water molecules were used, and for citrine, 9290 water molecules were used. All water molecules overlapping with the protein were removed. The particle mesh Ewald method47 was used to treat long range interactions with a 9-Å non-bonded cutoff. Energy minimization was performed using the adopted basis Newton–Raphson (ABNR) method.43 Each system was then neutralized by adding sodium counter ions: six sodium ions for RFP and 8 sodium ions for YFP. Water molecules that overlapped with the sodium ions were removed and ABNR energy minimization was performed again. The systems were then heated with a linear gradient of 50 K/ps from 50 K to 300 K. At 300 K, the systems were equilibrated for 2 ns with a 2 fs integration time step in the NVT (constant number, volume, and temperature) ensemble. The SHAKE algorithm48 was used to constrain the bonds connected with hydrogen atoms. This was followed by a 10 ns NVT dynamics simulation with 2 fs time steps for each protein that was used for analysis.

Implicit ligand sampling for molecular oxygen

The ILS (Ref. 28) is a computational method, which computes the potential of mean force (PMF) corresponding to the placement of a given small ligand such as O2 and CO, everywhere inside the protein. The calculated PMF describes the Gibb's free energy cost of having a particle located at a given position, integrated over all degrees of freedom of the system, except ligand position. Calculated PMF values also show the area accessible to the ligand with the associated free energy cost. We applied PMF/ILS calculations to the frames from our MD simulations to determine locations in a protein that are especially important for blocking, or facilitating oxygen passage, and to quantify the differences at these locations between FP variants. A total of 5000 protein conformations from a 10-ns MD trajectory were used for ligand sampling. Therefore, the free-energy value at each of the locations is the average obtained from ILS performed every 2 ps for the 10-ns MD simulation trajectory. For the free energy calculation at each location, 20 different rotational orientations of molecular dioxygen were sampled at each gird position with a volume element size of 1 Å3. The free energy is compared to a dioxygen molecule placed outside the protein in the surrounding water, where the free energy is defined to be zero. In the figures, all locations with a free energy below −2.0 kcal/mol are colored red, and all locations with a free energy above +10.0 kcal/mol are colored blue. The values of the free energy as a function of reaction coordinate were calculated for specific positions separated by ∼1 Å distance along the pathways, extending from outside the protein in the solvent, into the protein and leading to the chromophore. The pathways were determined from visual inspection as well as from the 3D grid data of free-energy values from ILS simulations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

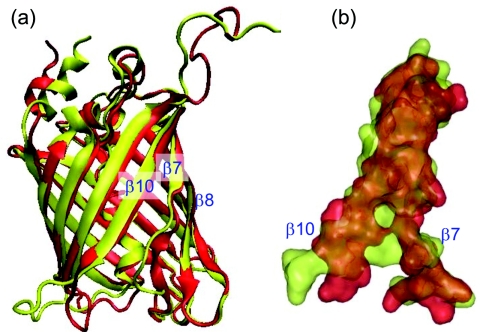

Results from 10 ns MD simulations comparing the monomeric mCherry RFP to the citrine YFP are shown in Fig. 2. Figure 2a displays the root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of each amino acid. The β7 strand in mCherry (amino acids 141–151) displays a significantly larger RMSF than β7 in citrine (amino acids 147–157), whereas for strand β10 the RMSF is approximately the same for mCherry (193–204) and citrine (199–208).

Figure 2.

Results from 10 ns MD simulations comparing the citrine YFP to the monomeric mCherry RFP. (a) Root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of each amino acid. (b) Time series of the separation between strands β7 and β10. Strands β7 and β10 show a large and fluctuating separation in mCherry as compared to the small, fixed separation in citrine.

To further investigate the possibility of oxygen access in this region, we next focus specifically on the opening between strands β7 and β10, which is the region that is postulated to allow oxygen entry for mCherry. Figure 2b is a time series of the separation between strands β7 and β10. The plots represent the separation Δr between a pair of residues, one residue on β7 and the other on β10. In order to characterize the size of the gap, an atom is chosen on each residue that is closest to the other residue across the gap. For mCherry, Δr is the distance between the Cα of residues Ala145 and Lys198, and for citrine, Δr is the distance between the Cα of residues Ser147 and Gln204. Not only is the β7-β10 gap always bigger in mCherry than citrine throughout the 10 ns, the gap in mCherry also exhibits larger fluctuations.

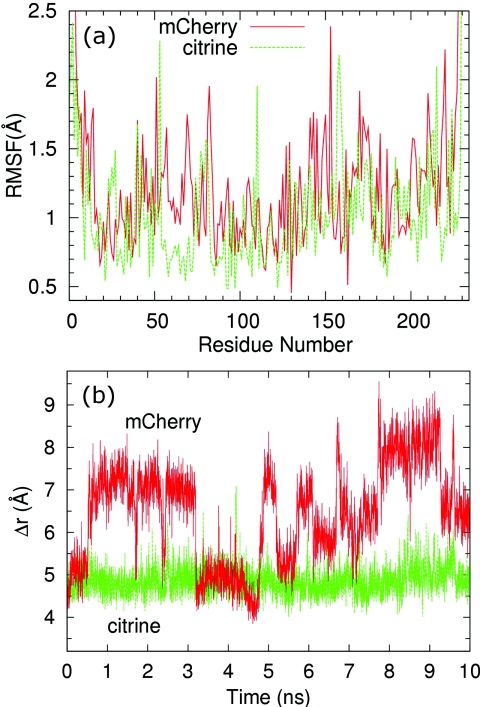

Dioxygen access routes to the chromophore in mCherry

The large and fluctuating gap between strands β7 and β10 displayed in Fig. 2 for mCherry but not for citrine, makes this region a prime candidate for dioxygen access in mCherry. To determine which regions or pathways allow the molecular oxygen to enter the protein barrel, we calculated the free energy of placing molecular oxygen in and around the entire protein barrel using ILS, which uses PMF calculations to determine the free energy of placing a small molecule such as dioxygen at a specific location in a protein. Figure 3a displays ensemble-averaged free-energy diagrams for a dioxygen molecule if it is placed in, or around, mCherry and compare that with citrine in Fig. 3b. We calculated the free energy of the dioxygen using the ILS routine implemented in the VMD molecular dynamics package.49 In Fig. 3a, we display a slice that includes the β7 region. The color red represents low free-energy (<−2 kcal/mole) locations, white represents intermediate free energy locations, and blue represents high free-energy (>+10 kcal/mol) locations. In order for the chromophore to have access to molecular oxygen, a pathway without substantial free-energy barriers must exist from the region outside the protein, through the protein barrel, to the chromophore location in the interior. Figure 3a shows that mCherry displays two low free-energy routes through the barrel: one through the β7-β10 gap (R1) and the other through the β7-β8 gap (R2). These two entry routes for dioxygen lead all the way to the chromophore. In contrast, citrine has no easy pathway, including the β7-β10 region (Y1) or the β7-β8 region (Y2) both of which involve high free-energy (blue) barriers.

Figure 3.

Free-energy isosurfaces for molecular dioxygen in (a) citrine and (b) mCherry. The free-energy slice shown includes the β7-β10 region as well as the β7-β8 region. The color red represents low free-energy (<−2 kcal/mole) locations, blue represents high free-energy (>+10 kcal/mol) locations, and white represents locations for which the oxygen has intermediate free energy. Neither the β7-β10 region nor the β7-β8 region in citrine offers low free-energy routes for dioxygen entry, whereas in mCherry both regions display gaps representing low free-energy access routes.

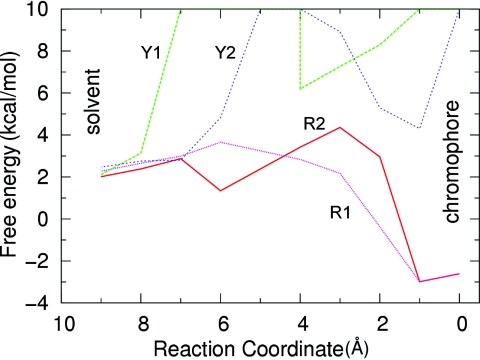

Figure 4 quantifies the value of the free energy along the pathways shown in Fig. 3. The reaction coordinate is the position of the oxygen molecule along the route. The oxygen molecule is placed at steps along the path that are separated by 1 Å. The coordinate 0 represents a location near the chromophore and 9 Å represents a location outside the protein in the solvent. It is seen in this figure that both routes in citrine (Y1, Y2) face large free energy barriers due to the protein barrel, whereas there is no substantial barrier for either of the pathways in mCherry (R1, R2). The identification of these pathways is used later to guide mutations of key residues in order to create barriers in mCherry to block these routes and prevent dioxygen access to the chromophore.

Figure 4.

Free-energy values of dioxygen at locations along the pathways shown in Fig. 3 leading from the solvent outside the protein (9 Å) into the chromophore (0 Å). The mCherry has two easy routes that can be accessed by entering through either the β7-β10 gap (R1) or the β7-β8 gap (R2). The routes for citrine through either the β7-β10 (Y1) region or β7-β8 (Y2) region are blocked by a high free-energy barrier.

Importance of sidechains in controlling gap size

As discussed in the Introduction, the β7-β10 gap and the β7- β8 gap in mCherry are large enough to allow dioxygen to pass through the protein barrel to the chromophore. An aim of this work is to determine if site-specific amino acid mutations can alter these routes. In order to ascertain more details of the structural fluctuations in the barrel, we determined if the large fluctuations in the mCherry β7-β10 gap is due to motion of strand β7 or strand β10, and similarly for the β7-β8 gap.

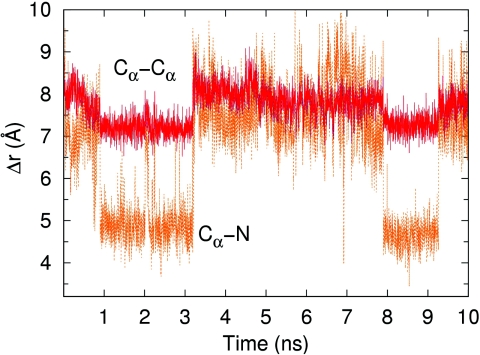

In comparing the time series of the fluctuations in the size of the mCherry β7-β10 gap (Fig. 2b) and the β7-β8 gap, we found that the openings and closings of the gaps were out of phase with each other. When the β7-β10 gap is large, the β7-β8 is small, and vice versa, implying that the fluctuations in the β7-β10 gap and the β7-β8 gap are mostly due to movement of β7. In addition, to provide more information for guiding the mutations, we wish to determine why Figs. 34 both show that the dioxygen pathway through the β7-β8 gap (R2) is not as easy as the pathway through the β7-β10 gap (R1) even though the backbone separations are similar. In Fig. 5 we show that amino acid sidechains play an important role in closing the β7-β8 gap. Figure 5 displays the results of 10 ns MD simulations for the separation between strands β7 and β8 determined in two different ways. For both time series, the separation is measured between Ala145 on β7 and Gln163 on β8. One plot shows the time series of fluctuations in the separation between the amino acids’ Cα atoms. The other time series displays the fluctuating distance between the Cα of Ala145 (on β7) and the N on the sidechain of Gln163 (on β8). Figure 5 shows that the sidechain of Gln163 narrows the gap significantly more than the backbone.

Figure 5.

Fluctuations in the β7-β8 gap in mCherry determined by the distance between Cα atoms of β7-Ala145 and β8-Gln163 (darker line) compared to the separation determined by the distance between Cα on β7-Ala145 and the N on the sidechain of β8-Gln163 (lighter line). The sidechain of Gln163 narrows the gap significantly more than the backbone.

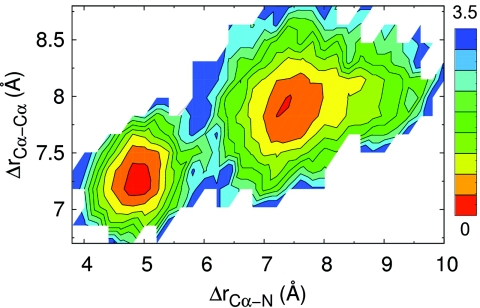

Figure 6 further quantifies the importance of sidechains for determining gap sizes. In Fig. 6, we present a contour plot of the free energy of Ala145 on β7 and Gln163 on β8 as a function of their separation, measured in the same two ways that are used in Fig. 5. The vertical axis is the separation between the Cα of residue β7-Ala145 and the Cα of residue β8-Gln163 (dark line in Fig. 5) and the horizontal axis is the separation between the Cα of β7-Ala145 and the N on the sidechain of residue β8-Gln163 (light line in Fig. 5). Figure 6 shows that there are two islands of low free energy, which implies that β7 is stable at two distinct separations from β8, with the larger separation meaning that β7 is closer to β10. Another important feature is that when β7 is further from β8, the range of fluctuations in the sidechain of β8 is also larger. This allows the large side chain of β8 to partially close the gap even when β7 is far away.

Figure 6.

Free-energy plot (in kcal/mol) of the β7-β8 strands. The horizontal axis is the separation between the Cα on β7-Ala145 and the N on the sidechain of β8-Gln163, the vertical axis is the separation between the Cα of β7-Ala145 and the Cα of β8-Gln163. There are two distinct islands of low free energy, showing that the β7 strand spends most time in these two distinct positions. Additionally, when the Cα-Cα separation is large, the sidechain undergoes larger fluctuations, which restricts the gap from opening widely.

Amino acid mutations in mCherry to control dioxygen access to the chromophore

Figures 34 show that the easiest pathway for oxygen access in mCherry is through the gap between β7 and β10, and Figs. 56 show that sidechains play a role in closing the β7-β8 gap. Therefore, our aim in making amino acid mutations is to decrease the β7-β10 gap without substantially increasing the size of the gap between β7 and β8.

On comparing amino acid properties of the residues in the β7, β8, and β10 strands of mCherry and citrine, it is seen that there are more charged residues in mCherry as compared to just two in β8 of citrine. The citrine residues in the region of interest are mostly polar (Ser, Tyr, Asn, His) or hydrophobic (Ala, Val, Phe, Ile, Leu). We first attempted a few mutations in mCherry such that the charged amino acids are replaced by polar or hydrophobic residues, similar to the pattern in citrine. This change, however, either made the fluctuations worse or the β7-β10 gap increased even further. Since the β7-β10 gap fluctuates the most, a possible strategy to reduce this fluctuation is to create appropriate ionic interactions. In this region of mCherry, the inter-strand charged amino acid residues participate in inter-strand ionic interactions and give rise to salt-bridges. For example, the attractive interaction between Glu144(-) in β7 and 164Arg(+) in β8 swings β7 towards β8 and helps to open the gap between β7 and β10. To reduce the barrel flexibility in this region, we made two amino acid replacements (one in β7 and other in β8): we replaced the polar 143Trp in β7 by a positively charged 143Lys(+), and the 164Arg(+) in β8 was replaced by 164Glu(-). The mutations introduce two possible electrostatic interactions that might close the β7-β10 gap. The attraction between the mutated β7 143Lys(+) and β10 200ASP(-) pulls β7 towards β10, and the repulsion between β7 Glu144(-) and the mutated β8 164Glu(-) pushes β7 away from β8 and towards β10. Since the location of the gap is close to the original tetramer-breaking mutations, the barrel folding in monomeric form can be sensitive to new mutations such as the one presented here. A new set of mutations must still allow the barrel to fold and chromophore to mature. If this is achieved, the marked reduction in the barrel fluctuations that limit the oxygen entry may result in a more photostable FP.

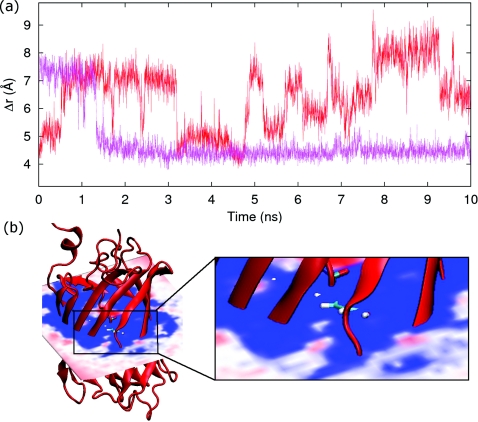

The success of the mutations in closing the β7-β10 gap in the mutated RFP (mut-RFP) is shown in Fig. 7. The two curves display time series for mCherry (same curve as in Fig. 2b) and mut-RFP for the β7-β10 gap. The β7-β10 gap in Fig. 7 for the mut-RFP starts out at ∼7.5 Å, which is as large as it ever gets for mCherry. This is expected because the initial positions for the atoms in our proposed mut-RFP are given by the PDB file for mCherry. Within a short time, Fig. 7a shows that new interactions in mut-RFP greatly reduce the β7-β10 gap compared to mCherry which significantly reduces the ease of oxygen permeability as displayed by the free-energy isosurface in Fig. 7b.

Figure 7.

(a) Results from the 10 ns MD simulation of the β7-β10 gap for mCherry (red, same curve as in Fig. 2b) compared to its mutant (purple). The β7-β10 gap in mut-RFP is greatly reduced compared to mCherry. (b) Free-energy isosurface for molecular dioxygen in mut-RFP. As compared to the isosurface displayed in Fig. 3b for mCherry, mut-RFP isosurface shows significantly less favorable pathways for oxygen entry with high free-energy barriers (blue).

We have used MD calculations to determine the pathways for molecular oxygen entry through the barrel of mCherry. We have shown that specific point mutations can alter the oxygen pathways in the RFPs. Blocking or altering these pathways through the barrel can have an effect on FP maturation as well as on its photostability. For example, easy oxygen access may significantly reduce the photostability whereas it may be useful for chromophore maturation, especially at low oxygen conditions. The computational approach can provide important insights for guiding efficient mutagenesis experiments to improve the maturation speed and photostability of mFruits.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Award No. SC3GM096903 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Professor Ralph Jimenez at the University of Colorado at Boulder for bringing this topic to our attention. We also thank Professor Jimenez for critical reading of the paper and many helpful discussions.

References

- Tsien R. Y., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 509 (1998). 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer M., Chem. Rev. 102(3), 759 (2002). 10.1021/cr010142r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M., Tu Y., Euskirchen G., Ward W. W., and Prasher D. C., Science 263(5148), 802 (1994). 10.1126/science.8303295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding A., Shrestha S., Dria K., Hunt E., and Deo S. K., Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 21(2), 101 (2008). 10.1093/protein/gzm075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz M. V., Fradkov A. F., Labas Y. A., Savitsky A. P., Zaraisky A. G., Markelov M. L., and Lukyanov S. A., Nat. Biotechnol. 17(10), 969 (1999). 10.1038/13657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough D., Wachter R. M., Kallio K., Matz M. V., and Remington S. J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98(2), 462 (2001). 10.1073/pnas.98.2.462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R. E., Tour O., Palmer A. E., Steinbach P. A., Baird G. S., Zacharias D. A., and Tsien R. Y., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99(12), 7877 (2002). 10.1073/pnas.082243699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird G. S., Zacharias D. A., and Tsien R. Y., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97(22), 11984 (2000). 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzlyak E. M., Goedhart J., Shcherbo D., Bulina M. E., Shcheglov A. S., Fradkov A. F., Gaintzeva A., Lukyanov K. A., Lukyanov S., Gadella T. W., and Chudakov D. M., Nat. Methods 4(7), 555 (2007). 10.1038/nmeth1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner N. C., Campbell R. E., Steinbach P. A., Giepmans B. N., Palmer A. E., and Tsien R. Y., Nat. Biotechnol. 22(12), 1567 (2004). 10.1038/nbt1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner N. C., Steinbach P. A., and Tsien R. Y., Nat. Methods 2(12), 905 (2005). 10.1038/nmeth819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner N. C., Lin M. Z., McKeown M. R., Steinbach P. A., Hazelwood K. L., Davidson M. W., and Tsien R. Y., Nat. Methods 5(6), 545 (2008). 10.1038/nmeth.1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amara P., Andreoletti P., Jouve H. M., and Field M. J., Protein Sci. 10(10), 1927 (2001). 10.1110/ps.14201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. L., Regan R. M., and Gibson Q. H., Biochemistry 35(4), 1125 (1996). 10.1021/bi951767k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossa C., Anselmi M., Roccatano D., Amadei A., Vallone B., Brunori M., and Di Nola A., Biophys. J. 86(6), 3855 (2004). 10.1529/biophysj.103.037432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb D. C., Arcovito A., Nienhaus K., Minkow O., Draghi F., Brunori M., and Nienhaus G. U., Biophys. Chem. 109(1), 41 (2004). 10.1016/j.bpc.2003.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson Q. H., Regan R., Elber R., Olson J. S., and Carver T. E., J. Biol. Chem. 267(31), 22022 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunori M. and Gibson Q. H., EMBO Rep. 2(8), 674 (2001). 10.1093/embo-reports/kve159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Kim K., King P., Seibert M., and Schulten K., Structure 13(9), 1321 (2005). 10.1016/j.str.2005.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feher V. A., Baldwin E., and Dahlquist F. W., Nat. Struct. Biol. 3, 516 (1996). 10.1038/nsb0696-516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz J. R. and Weber G., Biochemistry 12(21), 4171 (1973). 10.1021/bi00745a021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler W. and Stein D. L., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88(15), 6750 (1991). 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun D. B., Vanderkooi J. M., G. V.WoodrowIII, and Englander S. W., Biochemistry 22(7), 1526 (1983). 10.1021/bi00276a002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchini B. R., Nemser A. R., and Zimmer M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120(1), 1 (1998). 10.1021/ja973019j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shu X., Shaner N. C., Yarbrough C. A., Tsien R. Y., and Remington S. J., Biochemistry 45(32), 9639 (2006). 10.1021/bi060773l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justin R. G., Rosemary B., and Klaus S., J. Comput. Phys. 151(1), 190 (1999). 10.1006/jcph.1999.6218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roux B., Comp. Phys. Commun. 91(1–3), 275 (1995). 10.1016/0010-4655(95)00053-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Arkhipov A., Braun R., and Schulten K., Biophys. J. 91(5), 1844 (2006). 10.1529/biophysj.106.085746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Cohen J., Boron W. F., Schulten K., and Tajkhorshid E., J. Struct. Biol. 157(3), 534 (2007); 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Johnson B. J., Cohen J., Welford R. W., Pearson A. R., Schulten K., Klinman J. P., and Wilmot C. M., J. Biol. Chem. 282(24), 17767 (2007). 10.1074/jbc.M701308200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saam J., Ivanov I., Walther M., Holzhutter H. G., and Kuhn H., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104(33), 13319 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0702401104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saam J., Rosini E., Molla G., Schulten K., Pollegioni L., and Ghisla S., J. Biol. Chem. 285(32), 24439 (2010). 10.1074/jbc.M110.131193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R., Riley C., Chenprakhon P., Thotsaporn K., Winter R. T., Alfieri A., Forneris F., van Berkel W. J., Chaiyen P., Fraaije M. W., Mattevi A., and McCammon J. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106(26), 10603 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0903809106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Lund L., Shao Q., Gao Y. Q., and Raushel F. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(29), 10211 (2009). 10.1021/ja902557r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund L., Fan Y., Shao Q., Gao Y. Q., and Raushel F. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132(11), 3870 (2010). 10.1021/ja910441v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. S., Roitberg A. E., and Richards N. G., Biochemistry 48(51), 12272 (2009). 10.1021/bi901521d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle R., Guertin M., and Lague P., Proteins 75(3), 735 (2009). 10.1002/prot.22283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesbeck O., Baird G. S., Campbell R. E., Zacharias D. A., and Tsien R. Y., J. Biol. Chem. 276(31), 29188 (2001). 10.1074/jbc.M102815200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki A., Nagai T., and Mizuno H., Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 95, 1 (2005). 10.1007/b102208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachter R. M., Yarbrough D., Kallio K., and Remington S. J., J. Mol. Biol. 301(1), 157 (2000). 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekas A., Alattia J. R., Nagai T., Miyawaki A., and Ikura M., J. Biol. Chem. 277(52), 50573 (2002). 10.1074/jbc.M209524200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craggs T. D., Chem. Soc. Rev. 38(10), 2865 (2009). 10.1039/b903641p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evdokimov A. G., Pokross M. E., Egorov N. S., Zaraisky A. G., Yampolsky I. V., Merzlyak E. M., Shkoporov A. N., Sander I., Lukyanov K. A., and Chudakov D. M., EMBO Rep. 7(10), 1006 (2006). 10.1038/sj.embor.7400787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks B. R., Bruccoleri R. E., Olafson B. D., States D. J., Swaminathan S., and Karplus M., J. Comp. Chem. 4(2), 187 (1983). 10.1002/jcc.540040211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eswar N., Webb B., Marti-Renom M. A., Madhusudhan M. S., Eramian D., Shen M. Y., Pieper U., and Sali A., Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 15, 5.6-1 (2006). 10.1110/ps.062095806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B. T., Gosavi S., Finke J. M., Onuchic J. N., and Jennings P. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105(34), 12283 (2008). 10.1073/pnas.0804039105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig M., Karanicolas J., and C. L.Brooks3rd, J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 22(5), 377 (2004). 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich E., Lalith P., Max L. B., Tom D., Hsing L., and Lee G. P., J. Chem. Phys. 103(19), 8577 (1995). 10.1063/1.470117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Gunsteren W. F. and Berendsen H. J. C., Mol. Phys. 34(5), 1311 (1977). 10.1080/00268977700102571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W., Dalke A., and Schulten K., J. Mol. Graphics 14(1), 33 (1996). 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]