Abstract

Background

The vast majority of individuals with alcohol problems in the U.S. and elsewhere do not seek help. One policy response has been to encourage institutions such as criminal justice and social welfare systems to mandate treatment for individuals with alcohol problems (Speiglman, 1997). However, informal pressures to drink less from family and friends are far more common than institutional pressures mandating treatment (Room et al., 1996). The prevalence and correlates of these informal pressures have been minimally studied.

Methods

This analysis used data from five Alcohol Research Group National Alcohol Surveys (NAS) collected at approximately five-year intervals over a 21 year period (1984 to 2005, pooled N=16,241) to describe patterns of pressure that drinkers received during the past year from family, friends, physicians, police and the workplace.

Results

The overall trend of pressure combining all six sources across all five NAS surveys indicated a decline. Frequent heavy drinking and alcohol related harms also declined and both were strong predictors of receiving pressure. Trends among different sources varied. In multivariate regression models pressure from friends showed an increase. Pressure from spouse and family showed a relatively flat trajectory, with the exception of a spike in pressure from family in 1990.

Conclusions

The trajectory of decreasing of pressure over time is most likely the result of decreases in heavy drinking and alcohol related harm. Pressure was generally targeted toward higher risk drinkers, such as heavy drinkers and those reporting alcohol related harm. However, demographic findings suggest that the social context of drinking might also be a determinant of receiving pressure. Additional studies should identify when pressure is associated with decreased drinking and increased help-seeking.

Keywords: Pressure, Coercion, Social Influence, Confrontation, Alcohol Problems

Over the past two decades a growing body of research has substantiated the notion that characteristics of the social environment have a strong impact on alcohol and drug use, help seeking, and treatment outcome (e.g., Beattie,et al., 1993; Kadushin, et al., 1998; Longabaugh, et al., 1993; Matzger et al., 2005; Moos and Finney, 1996; Szalay, et. al., 1996). However, one aspect of social network influence that is common yet understudied is the pressure that many drinkers receive to change their drinking or seek help. Room and colleagues (1996) found that 35% of the general public in Ontario, Canada had commented on a friend’s or relative’s drinking within the past year and 15% had suggested the person get help. In a US population study, Room, et al. (1991) found that 44% of a US population sample stated they had said something to friends or relatives about their drinking or had suggested they cut down.

Studies in the U.S. examining treatment entry have documented that large proportions report they received pressure to enter treatment from personal relationships (friends or family) or institutions (criminal justice and social welfare) (Polcin and Weisner, 1999). Characteristics of individuals entering treatment who report receiving pressure from family and friends were most likely to be those who were white and younger (Polcin and Beattie, 2007; Polcin and Weisner, 1999). A study that looked at pressure from both criminal justice and welfare institutions found that minorities were more likely than whites to receive mandates from these institutions to enter treatment (Polcin and Beattie, 2007).

Room et al (2004) used a broad definition of pressure that included pressure to change drinking or enter treatment among a mix of treated (n=926) and untreated (n=672) problem drinkers in one U.S. county. They found that pressure was most common from one’s spouse; but pressure from other family members was also frequent. Severity of alcohol dependence and alcohol related problems were strong predictors of receiving pressure.

Few studies have looked at how receiving pressure and its correlates vary at different points in time. However, Room et al (1991) used Alcohol Research Group National Alcohol Surveys (NAS’s) in the U.S. between 1979 and 1990 to document that receipt of pressure to drink less or act differently when drinking increased over time. They suggested that the increase in receipt of pressure may have been due to an increased awareness of alcohol problems that resulted from more prevention efforts and public education about alcohol during the 1980’s. Consistent with other studies, men and individuals who were younger reported more pressure, and spouse was a common source of pressure. However, the authors also noted several interesting trends. Between 1979 and 1990 there was an especially high increase in individuals reporting pressure from family members other than spouse, particularly mothers.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports documenting trends in the U.S. of pressure to change drinking since the Room et al (1991) paper. In addition, while Room et al (1991) assessed pressure from family and friends, other sources of pressures were not included, such as pressure to change drinking received from physicians, police, or the workplace.

Purpose

This paper describes 21-year trends in the types of pressures that U.S. drinkers received (i.e., family, friend, workplace, doctor, and police) and how receiving pressure varied by drinker characteristics, such as demographics, heavy drinking and alcohol related harm. Using five NAS datasets collected over a 21-year time period, the aim is to show how the trajectories of different types of pressures varied from 1984 to 2005 and whether individuals receiving more pressure were those for whom reducing their drinking may have been warranted (i.e., had higher volume of alcohol consumption and more alcohol related harms). We hypothesized that trends for receipt of pressure over the 5 time points would increase for all sources of pressure. In part, this hypothesis was based on the fact that Room et al (1991) reported increasing pressure from families and friends between 1979 and 1990. We expected these trends to continue to the present, particularly because environmental prevention strategies that emphasize social control over drinking increased during the 1990’s (NIAAA, 2000). We also knew from previous analyses using NAS data that heavy drinking has declined over the last 2 decades (Kerr, et al, 2009) and surmised that increasing pressure may have played a role.

Controlling for NAS time points, we hypothesized that the characteristics of individuals receiving more pressure would be younger, white, and married. We also hypothesized that heavier drinking and alcohol related harm would be associated with receipt of more pressure. These hypotheses were based on previous research on pressure reported by Room et al (1991), Polcin and Weisner (1999), and Polcin and Beattie (2007).

Methods

Survey Data

Scientists at the Alcohol Research Group have used National Alcohol Surveys (NAS) since 1979 to document trends in alcohol consumption among U.S. residents age 18 and older. NAS surveys have also tracked related variables, such as the social contexts of drinking and the prevalence of various types of alcohol related harm. NAS surveys are unique in capturing historical trends in alcohol consumption and problems because most other national surveys have only assessed recent time periods. For example, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health only tracks alcohol use back to 2002. Similarly, the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) only goes back to 2001. One national survey where there was concordance with the general direction of drinking trends reported in the NAS was NIAAA surveillance Report #85, which tracked per capita alcohol consumption between 1970 and 2006 (Latkins, et al., 2008). Like findings reported on the NAS, they found a decreasing trend in alcohol consumption relative to the mid 1980’s. Unfortunately, they did not track alcohol related harm.

The five administrations of the Alcohol Research Group’s National Alcohol Surveys (N7 [1984], N8 [1990], N9 [1995], N10 [2000], and N11 [2005]) have a high degree of comparability between them, particularly in highly similar item content. Several differences in the surveys include over-sampling for Latino/Hispanics and African Americans in four surveys (N7, N9, N10 and 11) and use of random digit dial (RDD) telephone survey methods for the last two surveys (N10 and N11) while the earlier surveys were multi-stage clustered samples using in-person interviews. All surveys were weighted to the U.S. general population. Therefore, the over-sampling should not bias the results because they are accounted for by the weights in the analysis (Kerr et al., 2004). The switch from face-to-face interviews with stratified cluster sampling in N7–N9 to RDD telephone interviews in N10 and N11 was accompanied by extensive methodological work comparing these two modes during the same time period, which found prevalence estimates of major drinking behaviors to be substantively comparable, in spite of the lower response rates for the telephone interviews (Greenfield et al., 2000; Midanik, et al., 1999; Midanik et al., 2001a; Midanik et al., 2001b; Midanik et al., 2003a; Midanik et al 2003b).

Two types of evidence indicate that the lower response rate in a telephone survey did not significantly bias results related to consumption measures. First, an extensive series of methodological studies comparing identical questions in telephone and in-person surveys during the same time points have found comparable estimations of mean alcohol consumption (Greenfield et al., 2000; Midanik and Greenfield, 2003a; Midanik and Greenfield, 2003b), with somewhat inconsistent but still modest interview mode effects for alcohol harms (Midanik et al., 2001a; Midanik et al., 2001b). Second, an analysis comparing consumption estimates in the NAS sample replicates (each a random subsample, successively ‘opened’ during the conduct of the survey, and each with a specific response rate varying around the overall mean of 58%) a finding of no significant correlation between replicate response rate and volume of consumption (Kerr et al., 2004), again suggesting that telephone estimates of consumption are somewhat insensitive to response rate above and below the range typically obtained for telephone surveys (Greenfield et al., 2006). While these studies support the comparability of NAS survey methods (in-person versus telephone), it should be noted that not all NAS variables were included in these comparisons, including measures of pressure.

Described below are the six data sets to be used in the study:

N7 Survey

These data were collected in 1984 (N=5,221) by the Institute for Survey Research at Temple University. A multi-stage stratified sample of 100 primary sampling units (PSUs) was used. African Americans and Latino/Hispanics were over-sampled in 10 PSUs. The response rate was 77%.

N8 Survey

These data were collected in 1990 (N=2,058) by the Institute for Survey Research at Temple University using a multi-stage stratified sample of 100 PSUs. The response rate was 70%.

N9 Survey

These data were collected in 1995 (N=4,925) by the Institute for Survey Research at Temple University using a multi-stage stratified sample of 100 PSUs. The response rate was 77%.

N10 Survey

The data were collected in 2000 (N=7,612) by the Institute for Survey Research using a list assisted RDD method and Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) methods. African Americans, Latino/Hispanics and low population states were over-sampled. The response rate was 58%. The lower response rate than previous surveys is not unusual for telephone surveys (Kerr et al., 2004). This method of course has the advantage of collecting data on a larger number of individuals and lower design effects than for in-person surveys.

N11 Survey

The data were collected in 2005 (N=6,919) by Data Stat Inc. in Ann Arbor, Michigan. They again used a RDD CATI telephone survey. Again, African Americans, Latino/Hispanics and low population states were over-sampled. The response rate was 56%.

The NAS data series used here has been successfully used in a number of trend and age-period-cohort analyses, which together have added assurance of the suitability of this series of highly comparable surveys for conducting trend analysis (Greenfield and Kerr, 2008; Kerr et al., 2004; Kerr, et al., 2009, Kerr, et al., 2006).

Measures

Items used in different administrations of the NAS over time were designed to maximize consistency so we could compare differences between time periods. Thus, most items changed very little over time. The measures described below were all administered in N7-N11, except for a few measures where indicated.

Demographics

These items consisted of standard characteristics such as gender, age, race, marital status, and education and were used to describe the characteristics of who received pressure over the past 21 years.

Pressure

Pressure consisted of 6 items measuring pressure from spouse/someone lived with, family, friends, physicians, work, and police. Pressure was coded as a dichotomous variable indicating receipt of pressure over the past 12 months versus not receiving pressure. Four items directly asked whether the respondent experienced pressure to change drinking from four different sources. The wording of each item was geared to how we believed pressure from each source may have typically transpired:

My spouse or someone I lived with got angry about my drinking or the way I behaved while drinking.

A physician suggested that I cut down on drinking.

People at work indicated I should cut down on drinking.

A police officer questioned or warned me about my drinking.

Two additional sources, family and friends, asked whether “other people might have liked you to drink less or act differently when you drank.” Participants were specifically asked whether a variety of people ever felt that way including parents, other relatives, girlfriend or boyfriend and other friend. Parents and other relatives were combined into a “family” variable and girlfriend of boyfriend and other friend were combined into a “friend” variable. These questions were asked in terms of past 12 months and they were included in all of the NAS surveys used. This measure of pressure and variations of it have been used at ARG for many years (e.g., Hasin, 1994; Room, 1989, Room et al., 1991, Schmidt et al, 2007).

Table 1 shows the exact wording of pressure items at each time point. As indicated, the vast majority of questions across NAS administrations were exactly the same. In a few instances, minor word changes are evident. For example, N7 to N9 asked if “A policeman asked or warned me about my drinking.” N10 to N11 asked if “a police officer asked or warned me about my drinking.” N7 to N9 ask about pressure from a “mother” and “father,” whereas N10 to N11 ask about pressure from a “parent.”

Table 1.

Comparability of pressure questions across NAS survey years. All questions refer to the past 12 months.

| 3 | N7+ (1984) |

N8 (1990) |

N9 (1995) |

N10 (2000) |

N11 (2005) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Preface: Here are some experiences that many people have reported in connection with drinking. As I read each item, please tell me if this has ever happened to you? Did this happen during the last twelve months? |

x | x | x | x | x | |

| SPOUSE | A spouse or someone I lived with got angry about my drinking or the way I behaved while drinking |

x | x | x | x | |

|

Preface: Now I’m going to read a list of some people who might have liked you to drink less or act differently when you drank. For each one, please tell me if that person ever felt this way. Did this happen in the last 12 months? |

x | x | x | x | x | |

| FAMILY^ | Did a parent ever feel this way? | x | x | |||

| Your mother? | x | x | x | |||

| Your father? | x | x | x | |||

| Did any other relative ever feel this way? | x | x | x | x | x | |

| FRIEND& | Did a girlfriend or boyfriend ever feel this way? | x | x | x | x | x |

| Did any other friend ever feel this way? | x | x | x | x | x | |

|

Preface: Here are some experiences that many people have reported in connection with drinking. As I read each item, please tell me if this has ever happened to you? Did this happen during the last twelve months? |

x | x | x | x | x | |

| PHYSICIAN | A physician suggested I cut down on drinking. | x | x | x | x | x |

| WORK | People at work indicated that I should cut down on drinking |

x | x | x | x | x |

| POLICE | A police officer questioned or warned me because of my drinking |

x | x | |||

| A policeman questioned or warned me because of my drinking |

x | x | x | |||

Pressure from family is a ‘yes’ response to either ‘parent’ or ‘other relative’.

Pressure from friends is a ‘yes’ response to either ‘girl/boyfriend’ or ‘other friend’.

N7 (1984) pressure from family and friends is indicated only if the pressure broke up or threatened to break up the relationship.

A more substantive difference was for N7 items on 2 sources, family and friend, where a more conservative threshold was used to identify pressure. In that administration pressure from family and friends was only documented if the participant responded yes to a question asking “Did that break up your relationship with that person or threaten to break it?” Thus, pressure from family and friends in N7 represents a conservative finding.

Another more conservative measure was that of family pressure in the N8 survey, where there were questions about pressure from specific relationships that were not used during other years. These included questions about pressure from a brother, sister, son and daughter. Because other years did not specify these relationships, we did not include them in the analysis. Instead, we used a measure that that indicated pressure from mother, father, or any “other relative” for all NAS years. However, in the N8 data the “other relative” category is more conservative because it excludes brother, sister, son and daughter.

It should be noted that our assessment of pressure is broader than previous examinations of pressure using NAS datasets (i.e., Room et al., 1991). For example, Room et al (1991) did not study pressure from physicians, work, or police. In addition, they used a different measure of pressure from spouse. They asked respondents if their spouse “might have liked you to drink less or act differently when you drank.” Because our measure of pressure from one’s spouse measured a reported behavior (i.e. “got angry”) rather than the respondent’s perception about how the spouse might have felt about drinking, we think it is the stronger of the 2 measures. However, on 2 of the sources of pressure Room et al studied (i.e., family and friends) we used the same measure of pressure: “might have liked you to drink less or act differently when you drank.”

Frequent Heavy Drinking

To assess volume we used procedures similar to those described by Nyaronga et al (2009) . Overall alcohol consumption volume was assessed using the “Knupfer Series” (KS) beverage-specific, graduated-frequencies items (Greenfield, 2000). The KS items first ask the frequencies of drinking wine, beer, and distilled spirits (separately) using a nine-level categorical scale, followed in each case by asking the proportion of time the respondent drinks each beverage in three quantity ranges: one to two, three to four, and five or more drinks (response categories were the same as for the context of drinking variables). Overall volume is calculated by summing the responses with an appropriate algorithm (Greenfield, 2000) using a log transform to reduce the skew. Respondents reporting 5 or more drinks in a sitting on at least a weekly basis in the past 12 months were considered to be frequent heavy drinkers.

Alcohol Related Harm

Alcohol related harm was assessed using items that asked, “During the last 12 months, how often has your drinking had a harmful effect on your: 1) work and employment opportunities, 2) home life/marriage, 3) friendships and social life, 4) health, and 5) financial position.” Items were coded yes if the harm occurred during the last 12 months. Previous use of these items yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.73 (Greenfield et al., 2010).

Analysis Plan

Because we were interested in pressure received as a result of drinking behavior, we selected for our analysis only those respondents who indicated they were current drinkers (i.e., consumed alcohol during the past 12 months). This included a majority of individuals taking part in the NAS surveys, and it ranged from 61% at N10 (year 2000) to 69% at N7 (year 1984) and did not differ significantly across the survey years.

The analytic plan began with descriptive statistics documenting demographic and drinking characteristics of the 5 pooled datasets. We then used descriptive statistics to examine trends of receipt of pressure to change drinking from different sources over the five time points. To assess the relative influence of demographic factors on receipt of pressure from different sources at different time points we implemented multivariate logistic regression models. Separate models were conducted for each of the 6 sources of pressure as well as an overall model that assessed pressure from any of the 6 sources combined. Pressure was dichotomized as receiving pressure versus not and predictor variables included survey time point (N7 – N11) and demographic characteristics. The logistic regression models assessed how frequent heavy drinking and alcohol related harms predicted receipt of pressure after controlling for the demographic characteristics and dataset.

Results

Characteristics of the Sample

The demographic and drinking characteristics of the sample at each time point are shown in Table 2 along with the pooled sample that combined the datasets together. In the pooled sample, slightly over half were male, and most were white (77%) and married (66%). Over 55% had at least some college and those between the ages of 30 and 49 constituted 43% of the sample.

Table 2.

Demographic and drinking characteristics by NAS year among current drinkers (weighted percents).

| 1984 (N7) |

1990 (N8) |

1995 (N9) |

2000 (N10) |

2005 (N11) |

Pooled | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=3,212 | N=1,326 | N=2,817 | N=4,630 | N=4,256 | N=16,241 | |||

| Demographics | % | % | % | % | % | X2 | P | % |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 51.4 | 52.5 | 53.6 | 51.7 | 51.0 | 5.9 | 0.46 | 51.8 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–29 | 34.5 | 29.8 | 23.1 | 25.1 | 20.8 | 275.9 | <0.00 | 25.9 |

| 30–49 | 37.4 | 41.8 | 49.2 | 45.3 | 42.6 | 43.4 | ||

| 50+ | 28.1 | 28.4 | 27.8 | 29.7 | 36.5 | 30.7 | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| LT high school | 19.4 | 18.3 | 13.2 | 9.4 | 7.0 | 803.9 | <0.00 | 12.2 |

| HS graduate | 37.4 | 39.3 | 35.6 | 29.4 | 25.6 | 31.9 | ||

| some college | 22.9 | 20.8 | 26.5 | 28.8 | 27.3 | 26.1 | ||

| college graduate | 20.3 | 21.6 | 24.7 | 32.5 | 40.1 | 29.8 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 63.7 | 63.8 | 68.1 | 65.6 | 68.6 | 39.9 | 0.01 | 66.4 |

| sep/wid/div | 15.1 | 16.0 | 14.9 | 14.1 | 13.9 | 14.6 | ||

| never married | 21.1 | 20.2 | 16.9 | 20.3 | 17.6 | 19.1 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 83.6 | 75.4 | 79.7 | 77.4 | 75.8 | 172.2 | <0.00 | 77.4 |

| African-American | 9.2 | 12.0 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 9.3 | ||

| Hispanic | 5.2 | 9.0 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 8.5 | ||

| Other | 2.0 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 5.5 | 3.9 | ||

| Drinking characteristics | ||||||||

| 5+ weekly drinker | 13.9 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 8.4 | 7.2 | 110.6 | <0.00 | 9.4 |

| 1+ alcohol-related harms | 12.1 | 10.7 | 8.0 | 9.2 | 4.8 | 141.7 | <0.00 | 8.5 |

Proportions for gender and marital status were relatively consistent over NAS time points. However, in 1984 the proportion of the sample that was Hispanic was about half of what it was in 2005. In contrast, whites constituted 84% of the sample in 1984 and that dropped to 76% in 2005. The proportion of the sample that was age 18 to 29 decreased over the five NAS administrations and there was a doubling of the proportion reporting completion of a college degree.

In terms of drinking characteristics, we found a large reduction in alcohol related harms over the 5 NAS surveys, with 12.1% reporting at least one harm in 1984 and 4.8% in 2005. Frequent heavy drinking also showed a decline over time. During the 1984 survey 13.9% were assessed as frequent heavy drinkers and that proportion declined to 7.2% in 2005.

Receipt of Pressure over NAS Survey Time Periods

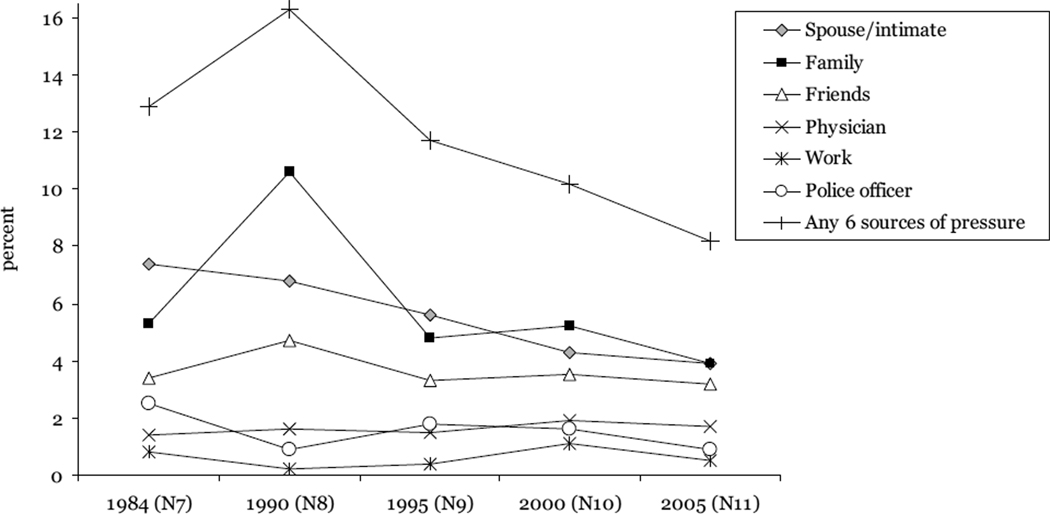

When we examined how receipt of pressure to change drinking varied over time we unexpectedly found that overall it decreased. Although the trend was not consistent across all time points, Figure 1 shows that the percent reporting pressure during the last 12 months from at least 1 of the 6 sources decreased significantly, from 12.9% in 1984 to 8.2% in 2005 (X2=92.2, p<.001). The trends of receiving pressure varied considerably depending on the source. Pressure from physicians and friends were relatively consistent over time. Statistically significant differences were found for spouse, family, police officer, and any of the 6 sources (all significant at p<.001 using chi square analyses). Some of these trends showed significant decreases over time, such as pressure from spouses, which decreased by almost half from 1984 to 2005. Warning about drinking from police officers was almost three times as high in 1984 as in 2005.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of past 12 month pressure among current drinkers by NAS year and pooled ( weighted percents).A

A between group X2 comparisons show p<.001 for spouse/intimate, family, police officer, and any 6 sources of pressure.

The other two sources of pressure, family and work, showed more inconsistent patterns. Pressure from family showed a spike in reported pressure at the 1990 time point. Over 10% of the sample reported pressure from relatives in 1990, whereas all other time points reported proportions that were under 6%. Relative to other sources, pressure at work was rarer and the trend was inconsistent. Pressure was highest in 1984 (0.8%) and 2000 (1.1%) and significantly lower in 1990 (0.2%) and 1995 (0.4%).

Frequent Heavy Drinking and Alcohol Related Harm

Table 3 shows the proportions of those receiving pressure that were frequent heavy drinkers and had experienced at least one alcohol related harm for each source of pressure. Alcohol related harms were broken down into harms related to each source (e.g., drinking impacting health for pressure from a physician) and harms that were not related to the source. Each source of pressure in the far left column shows the percentage at each NAS time point for heavy drinking, one or more harms related to the source, and one or more harms not related to the source. In addition, there is a combined “any source” variable at the bottom. Large proportions of individuals receiving pressure were frequent heavy drinkers and many reported experiencing drinking related harm. Among those who reported receiving pressure in the combined analysis (N=1,924) 38.6% were frequent heavy drinkers and 44.9% had experienced at least one alcohol related harm during the past 12 months.

| 1984 (N7) |

1990 (N8) |

1995 (N9) |

2000 (N10) |

2005 (N11) |

Pooled | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | X2 | P | % | |

| Spouse/intimate | ||||||||

| 5+ weekly drinker | 54.5 | 27.8 | 40.1 | 42.7 | 41.6 | 390.7 | 0.02 | 43.9 |

| Harms not related to home life/marriage | 52.9 | 55.0 | 44.6 | 56.5 | 42.8 | 190.7 | 0.16 | 50.1 |

| Harmful effect on home life/marriage | 40.0 | 39.5 | 33.1 | 35.5 | 31.1 | 83.5 | 0.57 | 35.8 |

| Family | ||||||||

| 5+ weekly drinker | 53.9 | 28.1 | 28.7 | 40.6 | 32.9 | 573.2 | <0.00 | 38.0 |

| Harms not related to home life/marriage | 65.9 | 38.4 | 33.7 | 53.2 | 45.1 | 352.8 | 0.03 | 47.9 |

| Drinking had harmful effect on home life/marriage | 38.7 | 23.4 | 19.2 | 28.9 | 25.7 | 568.3 | 0.00 | 25.4 |

| Friends | ||||||||

| 5+ weekly drinker | 50.4 | 32.2 | 31.6 | 45.6 | 36.7 | 315.8 | 0.18 | 40.5 |

| Harms not related to friendships and social life | 46.5 | 52.2 | 42.2 | 63.1 | 38.7 | 536.2 | 0.03 | 48.9 |

| Drinking had harmful effect on friendships and social life | 42.6 | 40.4 | 21.7 | 34.3 | 28.6 | 343.4 | 0.19 | 33.1 |

| Physician | ||||||||

| 5+ weekly drinker | 44.8 | 53.6 | 56.3 | 47.7 | 48.3 | 84.8 | 0.90 | 49.4 |

| Harms not related to health | 56.8 | 39.6 | 26.5 | 35.7 | 50.9 | 608.1 | 0.09 | 42.3 |

| Drinking impacting health | 58.7 | 50.5 | 34.4 | 45.4 | 37.3 | 387.3 | 0.31 | 44.0 |

| Work | ||||||||

| 5+ weekly drinker | 80.6 | 100.0 | 66.4 | 55.0 | 66.3 | n/a | n/a | 63.1 |

| Harms not related to work and employment opportunities | 65.6 | 100.0 | 84.0 | 71.8 | 74.0 | n/a | n/a | 73.2 |

| Harmful effect on work and employment opportunities | 24.6 | 42.1 | 16.0 | 15.8 | 23.6 | 219.7 | 0.74 | 19.9 |

| Police officer & | ||||||||

| 5+ weekly drinker | 61.8 | 38.2 | 34.8 | 45.2 | 43.4 | 572.7 | 0.14 | 47.6 |

| 1+ harms | 70.5 | 60.2 | 48.2 | 60.6 | 49.7 | 443.6 | 0.32 | 59.3 |

| Any source of pressure | ||||||||

| 5+ weekly drinker | 49.2 | 28.5 | 33.3 | 39.0 | 36.1 | 311.8 | <0.00 | 38.6 |

| 1+ harms | 54.1 | 42.5 | 38.1 | 48.3 | 37.7 | 283.5 | <0.00 | 44.9 |

Within sources, the proportion of drinkers who received pressure who were heavy frequent drinkers varied from 63.1% for work to 38.0% for family. Individual harms that were relevant to specific sources of pressure were lower, varying from 19.9% (work) to 44% (physician). It can be noted that participants with one or more harms not related to a specific source of pressure represented larger proportions than those with harms related to the source of pressure. For example, among those receiving pressure from friends 33.1% reported their drinking had a harmful effect of their friendships. However, a more substantive proportion (48.9%) reported that they experienced one or more harms not related to friendships.

For those who reported pressure from police and physicians, the proportions that were frequent heavy drinkers and had experienced drinking related harm were consistent across NAS time periods. However, those who received pressure from a spouse had larger proportions of frequent heavy drinking in 1984 than other years. Pressure from family had larger proportions of frequent heavy drinker s and alcohol related problems in the 1984 and 2000 survey years. Pressure from friends showed larger proportions experiencing harms during 1990 and 2000 surveys.

Multivariate Analyses of Factors Predicting Receipt of Pressure

Table 4 shows the relative influence of frequent heavy drinking, alcohol related harms, demographic characteristics and NAS survey time period on receipt of pressure during the past 12 months. Logistic regression models examined pressure from individual sources as well as all sources combined.

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) of demographic characteristicsassociated with receipt of pressure in the past 12 months for current drinkers, weighted.

| Spouse | Family | Friends | Physician | Work | Police | Any 6 pressures | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| NAS year (ref=2005) |

||||||||||||||

| 1984 (N7) | 1.1 | (0.7, 1.5) | 0.7 | (0.5, 1.0) | 0.5B | (0.3, 0.7) | 0.5A | (0.3, 0.9) | 0.7 | (0.3, 1.9) | 1.4 | (0.8, 2.5) | 0.9 | (0.7, 1.2) |

| 1990 (N8) | 1.1 | (0.7, 1.7) | 2.1C | (1.5, 3.0) | 0.8 | (0.5, 1.3) | 0.6 | (0.3, 1.1) | 0.2A | (0.1, 0.8) | 0.5 | (0.2, 1.2) | 1.7C | (1.3, 2.1) |

| 1995 (N9) | 1.3 | (0.9, 1.8) | 1.0 | (0.7, 1.5) | 0.7 | (0.4, 1.1) | 0.7 | (0.4, 1.3) | 0.7 | (0.3, 1.6) | 1.7 | (0.9, 3.2) | 1.3 | (1.0, 1.7) |

| 2000 (N10) | 0.8 | (0.6, 1.1) | 1.0 | (0.7, 1.3) | 0.7A | (0.5, 0.9) | 0.9 | (0.6, 1.4) | 1.6 | (0.8, 3.1) | 1.3 | (0.8, 2.2) | 0.9 | (0.7, 1.1) |

| Sex (ref=female) |

||||||||||||||

| Male | 2.1C | (1.6, 2.7) | 1.3 | (1.0, 1.6) | 1.3 | (1.0, 1.8) | 1.4 | (1.0, 2.1) | 1.4 | (0.7, 2.9) | 2.8C | (1.9, 4.2) | 1.7C | (1.4, 2.0) |

| Age (ref=50+) |

||||||||||||||

| 18–29 | 3.5C | (2.4, 5.1) | 2.6C | (1.8, 3.6) | 4.7C | (3.1, 7.1) | 0.6 | (0.4, 1.1) | 1.4 | (0.7, 3.0) | 9.8C | (4.7, 20.5) | 2.9C | (2.3, 3.7) |

| 30–49 | 2.0C | (1.4, 2.9) | 1.4 | (1.0, 2.0) | 2.0B | (1.3, 3.0) | 0.9 | (0.6, 1.4) | 0.9 | (0.5, 1.8) | 5.2C | (2.6, 10.8) | 1.7C | (1.3, 2.1) |

| Race (ref=white) |

||||||||||||||

| Black | 1.1 | (0.8. 1.5) | 1.2 | (0.9. 1.6) | 1.4 | (1.0. 1.8) | 1.7A | (1.1. 2.5) | 1.5 | (0.8. 2.8) | 0.6A | (0.4. 0.9) | 1.0 | (0.8. 1.2) |

| Hispanic | 0.9 | (0.6, 1.2) | 1.7C | (1.3, 2.2) | 1.4A | (1.0, 2.0) | 1.7A | (1.1, 2.7) | 2.2A | (1.1, 4.1) | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.9) | 1.2 | (1.0, 1.5) |

| Other | 0.7 | (0.4, 1.1) | 1.0 | (0.6, 1.8) | 1.1 | (0.7, 2.0) | 1.8 | (0.8, 4.2) | 4.5A | (1.1, 17.7) | 0.9 | (0.5, 1.9) | 1.1 | (0.7, 1.6) |

| Education (ref=college+) |

||||||||||||||

| LT HS | 1.7B | (1.2, 2.5) | 2.0C | (1.4, 2.9) | 2.1B | (1.4, 3.3) | 1.3 | (0.8, 2.3) | 2.7A | (1.1, 6.2) | 3.8C | (2.0, 7.2) | 1.8C | (1.3, 2.3) |

| HS graduate | 1.1 | (0.8, 1.6) | 1.7A | (1.2, 2.3) | 1.7A | (1.1, 2.6) | 0.8 | (0.5, 1.2) | 2.0 | (0.9, 4.6) | 2.3B | (1.3, 4.2) | 1.3A | (1.0, 1.6) |

| Some college | 1.0 | (0.7, 1.5) | 1.4A | (1.0, 2.0) | 1.4 | (0.9, 2.2) | 0.7 | (0.4, 1.2) | 0.7 | (0.3, 1.6) | 1.9A | (1.0, 3.6) | 1.1 | (0.8, 1.4) |

| Marital Status (ref=married) |

||||||||||||||

| Never married | 0.6B | (0.4, 0.9) | 1.5A | (1.1, 2.1) | 2.8C | (1.8, 4.1) | 1.2 | (0.8, 1.9) | 1.8 | (0.9, 3.4) | 2.6C | (1.6, 4.2) | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.4) |

| Div/Wid/Sep | 0.5C | (0.4, 0.7) | 2.5B | (1.9, 3.1) | 3.4C | (2.5, 4.6) | 1.3 | (0.8, 1.9) | 1.0 | (0.5, 2.0) | 2.0B | (1.3, 3.1) | 1.6C | (1.3, 1.9) |

| Drinking typology (ref=LT 5+ weekly drinker) |

||||||||||||||

| 5+ weekly drinker | 4.1C | (3.1, 5.4) | 2.9C | (2.2, 3.7) | 2.7C | (2.0, 3.8) | 5.0C | (3.3, 7.6) | 5.6C | (2.9, 10.9) | 2.6C | (1.7, 3.9) | 5.3C | (4.2, 6.7) |

| 1+ harms not related to pressure source |

4.5C | (3.4, 6.1) | 5.2C | (3.9, 6.9) | 3.9C | (2.7, 5.6) | 2.0C | (1.3, 3.3) | 10.6C | (4.8, 23.6) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Harm specific to pressure source |

10.3C | (7.2, 14.8) | 3.2C | (2.2, 4.6) | 3.8C | (2.5, 5.8) | 8.1C | (5.0, 13.2) | 2.8B | (1.5, 5.3) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 1+ harms | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 6.7C | (4.3, 10.5) | 11.5C | (9.4, 14.1) |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Drinking Predictors

As hypothesized, frequent heavy drinking and alcohol related harm were strong, consistent predictors of receiving pressure within and across sources. In the combined analysis examining all 6 sources together, frequent heavy drinkers were over 5 times more likely than those drinking less than that amount to report receiving pressure. Further, frequent heavy drinking predicted receipt of pressure within all sources of pressure, ranging from an odds ratio of 2.7 (CI=2.0 – 3.8) for friends to 5.6 (CI= 2.9 – 10.9( for work.

There were similar findings for alcohol related harms as a predictor of pressure. Some sources of pressure had specific alcohol related harms that were relevant to them. For these sources we used models that assessed the relative influence of the harm that was relevant to that source as well an aggregate measure of non-specific harms that were not related to the source. One source (police) did not have an individual harm associated with it so we assessed the effects of any harm reported. Regardless of how harm was assessed, it was a significant predictor of receiving pressure within and across sources (Table 4). For harms that were relevant to sources, odds ratios ranged from 2.8 (CI= 1.5 – 5.3) for work to 10.3 (CI=7.2 – 14.89) for spouse. Harms not related to specific sources of pressure were also significant predictors of receiving pressure in all models. While specific harms related to pressure from spouse and physicians had higher odd ratios than non-specific harms, the opposite was the case for pressure from work and family, where non-specific harms were stronger predictors.

Demographic Predictors

Logistic regression models also assessed how demographic characteristics were associated with receipt of pressure controlling for frequent heavy drinking, alcohol related harms and NAS time period (see Table 4). In the overall analysis that assessed predictors of pressure from any of the 6 sources, sex, age, education, and marital status were all significant predictors. Men were 70% more likely than women to report pressure. Most of the difference can be attributed to men receiving more pressure from spouses (OR= 2.1, CI= 1.6 – 2.7) and police (OR=2.8, CI= 1.9 – 4.2).

Younger age groups also reported receiving more pressure. Those age 18–29 were 2.9 times (CI= 2.3 −3.7) more likely to report receiving pressure than those 50 and older. Those age 30 – 49 were 1.7 times (CI= 1.3 – 2.1) more likely to report receiving pressure than those 50 and older. Within source models showed that age predicted receipt of pressure from spouse, family, friends, and police.

In the combined analyses, race did not predict receipt of pressure. However, significant within source differences were noted for family, friends, physician, work and police. Hispanics received more pressure from family, friends, physicians, and work. African American participants received more pressure from physicians but less from police.

Relative to drinkers with a college degree, those with less than a high school education and those with a high school diploma but no college received more pressure. In the analysis predicting any of the 6 sources, those with less than a high school education were 80% more likely to report receiving pressure and that those with a high school diploma but no college were 30% more likely.

Among those with less than a high school education pressure was more likely for all sources except physicians. For those with a high school degree pressure was more likely from family, friends and police. As Table 4 indicates, the findings were fairly robust across sources, especially for those with less than a high school diploma.

As expected, drinkers who were married reported significantly more pressure from spouses. However, on other sources they tended to report less pressure. Relative to those who were married, drinkers who were divorced, widowed, or separated reported higher pressure from family, friends and police. In the analysis considering pressure from any source they were over 60% more likely than married drinkers to report receiving pressure. Although those who were never married did not differ from those who were married in terms of receipt of pressure from any of the six sources, they did receive significantly more pressure from friends (OR= 2.8 CI= 1.8 – 4.1), family (OR= 1.5 CI= 1.1 – 2.1) and police (OR= 2.6 CI= 1.6 – 4.2).

NAS Time Periods

One of our primary goals was to document how receipt of pressure to change drinking varied over the past 21 years. Descriptive trends (i.e., percentages) are described above and reported in Figure 1. When we looked as simple percent reporting pressure over time we saw a significant decline across the survey years. However, when we controlled for a variety of variables in the logistic regression models (Table 4) we had mixed findings. The overall model examining the 6 sources pooled together showed that compared to the most recent time point (2005) pressure was more common in 1990 (OR=1.7, CI= 1.3 – 2.1). Higher overall pressure in 1990 appears to have been driven largely by pressure from family, where the odds of receiving pressure were over twice as likely as 2005.

Although not reaching statistical significance, 1995 had a trend of more pressure relative to 2005 (OR=1.3, CI= 1.0 – 1.7; p=0.51). Within each source of pressure there was considerable variation in the trends of pressure over time. Again, the findings differed from the bivariate trends reported in Figure 1. For example, bivariate comparisons of pressure over time for friends and physicians did not reveal significant differences. However, in our multivariate models we found both were about half as likely to report pressure in 1984 compared to 2005 and friends was also significantly lower in 2000(OR=0.7, CI = ,0.5 – 0.9, p<.05). While pressure from spouse and police showed overall declines in the bivariate analyses, neither varied to any significant extent in the regression models.

Discussion

The overall trend of pressure over the 21-year time period indicated a significant decline. With the exception of an increase in 2000, the trend was consistent across NAS years. We saw similar trends for frequent heavy drinking and alcohol related harm. Like pressure, alcohol related harm had a consistent decline over the 21 year period except for an increase in 2000. Frequent heavy drinking had a declining trend except for an increase in 1995. However, when we conducted multivariate analyses of factors predicting pressure, included NAS dataset, we found the strongest, most consistent predictors were frequent heavy drinking and alcohol related harms.

Frequent Heavy Drinking and Harms

Regardless of the source of pressure or the time period when data were collected, the strongest and most consistent predictors of receiving pressure to change drinking in our multivariate models were frequent heavy drinking and alcohol related harms. For harms, we found individual harms that were conceptually related to specific sources of pressure (e.g., medical harm and pressure from physicians) predicted receipt of pressure from that source. However, we also found that aggregate measures of other harms that were not related to sources also predicted receipt of pressure. This was particularly evident when pressure was reported from a source that could include comments from multiple individuals, such as friends and family. Some suggestions from these sources appear to reflect concerns about problems unrelated to their relationship with the drinker, such as medical, legal or work problems the drinker was experiencing. While pressure from sources that reflect one individual (e.g., physicians and spouse) were associated with both related and unrelated harms, the odds ratios were stronger for harms related to sources.

The Social Context of Drinking

Although frequent heavy drinking and experiencing alcohol related harms were the strongest predictors of receiving pressure, other factors were important as well. More pressure was reported by participants who were male and unmarried, whereas older age individuals and those with a college degree reported less pressure. Overall, these findings are consistent with a variety of previous studies that examined demographic correlates of pressure to change drinking and coercion to enter treatment (e.g., Polcin and Weisner, 1999; Room et al., 1991; Room et al., 2004).

Who receives pressure to change their drinking may in part be determined by the social context where drinking takes place. For example, several papers (e.g., Polcin and Weisner, 1999; Weisner and Schmidt, 1995) pointed out that younger persons are more likely to have lifestyles where drinking is associated with problem behaviors that are likely to elicit comments (e.g., drinking in public settings and driving under the influence). Elderly drinkers are more likely to drink at home and therefore elicit fewer comments about drinking. In addition, if they are retired, pressure from the workplace is eliminated as a potential source.

The finding that men received more pressure than women from spouses is consistent with data reported by Room et al (1991) and in part a function of men having larger proportions of frequent heavy drinkers. Although gender roles have become increasingly flexible over the past several decades in terms of caretaking functions in families, women may still be more sensitive than men to the destructive effects of drinking on the family, the marriage, or potential financial consequences that could result from job loss. Thus, they may be more likely to comment on these concerns. The higher odds of men receiving pressure from police may be another function of the social context of drinking. Men are more likely than women to drink in contexts where problem behaviors such as driving under the influence come to the attention of police (Elliot, et al., 2006).

Understanding why those with higher education levels would experience less pressure may also be a function of the context where drinking takes place. Drinkers with a higher level of education and income might have access to resources that support drinking in situations where there is less risk for problems. These would include things like drinking more often in socially acceptable contexts, such as business and social events. There may also be a dynamic that involves others being less likely to pressure these individuals because they are of higher social status.

Having a spouse or live-in partner obviously adds as a potentially important source of pressure and is only an issue for those who are married or cohabitating. However, our findings indicated that, overall, unmarried individuals reported receiving more pressure. Being unmarried was associated with variables that predicted more pressure (i.e., younger and more heavy drinking). However, when we entered all these variables into multivariate models that parsed out their relative effects on pressure we still found marital status was a significant predictor. Again, the social context of drinking might play a role. It may be that those who are married have lifestyles that include drinking in situations where there is less likelihood of problem behaviors that are commented on by others. For example, there may be more drinking at home and less drinking at bars.

Relative Influences of NAS Time Points

We found pressure from families and friends increased between 1984 and 1990, which is consistent with the findings reported by Room et al (1991). However, an unexpected finding was that the overall incidence of receiving pressure, which included three sources not included by Room et al (1991) and a different measure of pressure from spouse, decreased over the 21-year time interval measured. Much of that decline appears to be due to decreases in frequent heavy drinking and alcohol related harms over the same time period. When we controlled for frequent heavy drinking, harms and demographics in the combined analysis examining pressure from any of the 6 potential sources, the 1984 time period did not differ from 2005.

We saw similar patterns for some of the individual sources of pressure. While pressure from police officers and spouses showed significant declines over time in the bivariate analyses, no declines were noted in the multivariate models. Thus, the changes we observed are likely due to the changes in frequent heavy drinking and alcohol related harms rather than other social or cultural factors unique to those time periods.

Multivariate analyses showed differences from the bivariate analyses in the other direction as well, where previously insignificant bivariate comparisons became significant predictors in the multivariate analyses. For example, neither friends nor physicians showed significant variation over NAS time points in the bivariate analyses (Figure 1), yet both were significant in multivariate models illustrated in Table 4. The odds of receiving pressure in 1984 from each of these sources were about half that of 2005. It should be noted that increases in pressure from family and physicians occurred even though relative to 1984 there were very large reductions heavy drinking and alcohol related harm.

Part of the increase in pressure from friends may be an artifact of the more conservative definition of pressure from friends that was used in 1984 relative to 1990 (see the measures section for a discussion of how the two measures differed). However, other factors may have been influential. There may have been increased awareness of alcohol problems resulting from prevention efforts and public education. During the 1980’s there was a significant push to increase prevention efforts in schools (Room et al., 1991). The types of interventions emphasized were often geared toward affecting peer friendships and creating social norms about moderate drinking. Thus, they may have played a role in increasing pressure from friends between 1984 and 1990. Other social and policy factors that might have been influential include the growth of groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) and the change in the minimum drinking age to 21 nationwide in 1984.

Our multivariate results for pressure from friends suggest that pressure leveled off during 1990 to 2000 and then increased in 2005. It could be that the effect of these types of interventions on increasing peer pressure had been maximized by 1990 and therefore did not increase further during the subsequent decade despite the fact that policies and social influences aimed at controlling drinking continued. It is unclear why there was an increase in pressure from friends in 2005, but it could be that the effects of social policy changes, such as increasing prevention efforts, have uneven and sometimes delayed effects. For an example of delayed policy effects see the work of Greenfield and Kaskutas (1998) on the effects of warning labels on alcohol beverages.

The relative increase in pressure from physicians in 2005 might be the result of the increasing emphasis on brief interventions in medical settings (Saitz, et al, 2006). Physician education about the medical effects of alcohol has increase as has education about the need to discuss alcohol with patients. As discussion about alcohol problems in these settings is increasing, it would presumably include advice about changing destructive drinking practices (i.e., pressure).

Implication and Future Research

Results can be used to inform public health, treatment, and prevention professionals that formal (police, work and physician) and informal (spouse, family and friends) pressures over the past 21 years have been targeted toward drinkers for whom decreasing their drinking is indicated: frequent heavy drinkers and those experiencing alcohol related harm. The fact that pressure from friends increased in 2005 relative to previous years may be an indication that prevention strategies that aim to increase peer pressure may be working. There may also be some support for efforts to increase assessment and brief intervention among physicians because pressure from them also increased in 2005 relative to previous years, although to a lesser extent. Of course receipt of pressure does not necessarily indicate beneficial impacts on drinking. Important areas for future research include addressing the question when pressure results in decreased drinking or increased help seeking. For example, when and for who does pressure result in changing drinking practices? What drinker characteristics are associated with an increase in help seeking in response to pressure?

Results also suggest there are potential benefits of harm reduction strategies that attempt to influence the context where drinking occurs. Demographic findings indicate that controlling for harms and frequent heavy drinking younger males with less education receive more pressure about their drinking. Problems associated with the context where these groups drink might be reduced through harm reduction activities. Examples include strategies to reduce drinking and driving, alcohol related assaults, unprotected sex and binge drinking.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations that are inherent to our study. First, all of the NAS data consists of self-reported information without corroborating sources to validate self-reports. Second, although alcohol related harms assessed a variety of areas, there are other potential harms not directly assessed, such as legal and emotional problems. Third, although extensive research has documented the equivalence of NAS datasets and the methods used to collect the data, there is nonetheless some degree of variation resulting from different data collection methods and wording of items across NAS years. In addition, the studies showing equivalence for data collection methods (in-person versus telephone) did not test for equivalence of pressure items. Fourth, because the measure of pressure from family and friends in N7 used a screen question, (“did that break up your relationship or threaten to break it up”), pressure for those two sources during that year is more conservative. As noted in the Measures section, the measure of family pressure used in N8 was more conservative because it did not capture all types of family relationships (i.e., brother, sister, son, and daughter). Fifth, there are potential factors affecting pressure that we were not able to assess because of limited N’s for some subgroups of participants. One example includes underage drinkers age 18 −21, who might have received increasing pressure when the minimum drinking age in the U.S. changed from 18 in many states to 21. Other examples include analyses of the association between pressure and heavy drinking and alcohol related harm combined and interactive effects of gender and heavy drinking. Finally, there are analyses that go beyond the scope of the current paper that we plan to present in future papers. These include the correlates of pressure and help-seeking and age-period-cohort effects on pressure.

Acknowledgements

Funded by NIAAA grant R21AA018174.

References

- Beattie MC, Longabaugh R, Elliott G, Stout RL, Fava J, Noel NE. Effect of the social environment on alcohol involvement and subjective well-being prior to alcoholism treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54(3):283–296. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot MR, Shope JT, Raghunathan TE, Waller PF. Gender differences among young drivers in the association between high-risk driving and substance use/environmental influences. J Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):252–260. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK. Ways of measuring drinking patterns and the difference they make: experience with graduated frequencies. J. Subst. Abuse. 2000;12(1):33–49. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Bond J, Roberts SCM, Polcin DL, Korcha R, Knibbe R, et al. Alcohol Harms, Pressure to Drink Less, and Considering Seeking Help: A cross-national multilevel GENACIS analysis, in 36th Annual Epidemiological Symposium of the Kettil Bruun Society for Social and Epidemilolgical Study of Alcohol. Lausanne, Switzerland: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Kaskutas LA. Five years’ exposure to alcohol warning label messages and their impacts: evidence from diffusion analysis. Applied Behavioral Science Review. 1998;6(1):39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Kerr WC. Alcohol measurement methodology in epidemiology: recent advances and opportunities. Addiction. 2008;103(7):1082–1099. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Midanik LT, Rogers JD. Effects of telephone versus face-to-face interview modes on reports of alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2000;95(2):227–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95227714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Nayak M, Bond J, Ye Y, Midanik LT. Maximum quantity consumed and alcohol-related problems: assessing the most alcohol drunk with two measures. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2006;30(9):1576–1582. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS. Treatment/self-help for alcohol-related problems: relationship to social pressure and alcohol dependence. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55(6):660–666. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadushin C, Reber E, Saxe L, Livert D. The substance use system: social and neighborhood environments associated with substance use and misuse. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33(8):1681–1710. doi: 10.3109/10826089809058950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age, period and cohort influences on beer, wine and spirits consumption trends in the US National Surveys. Addiction. 2004;99(9):1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age-period-cohort modeling of alcohol volume and heavy drinking days in the US National Alcohol Surveys: divergence in younger and older adult trends. Addiction. 2009;104(1):27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Midanik LT. How many drinks does it take you to feel drunk? Trends and predictors for subjective drunkenness. Addiction. 2006;101(10):1428–1437. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkins NE, LaVallee RA, Williams GD, Yi H-y. Surveillance Report # 85 [ http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance85/CONS06.pdf accessed 10/13/09] Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Division of Epidemiology and Prevention Research, Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System; 2008. Apparent Per Capita Alcohol Consumption: National, State, and Regional Trends, 1970–2006; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Beattie M, Noel N, Stout R, Malloy P. The effect of social investment on treatment outcome. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54(4):465–478. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzger H, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. Reasons for drinking less and their relationship to sustained remission from problem drinking. Addiction. 2005;100:1637–1646. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK. Defining “current drinkers” in national surveys: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Addiction. 2003a;98(4):517–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK. Telephone versus in-person interviews for alcohol use: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003b;72(3):209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Reports of alcohol-related harm: telephone versus face-to-face interviews. J Stud Alcohol. 2001a;62(1):74–78. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Hines AM, Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Face-to-face versus telephone interviews: using cognitive methods to assess alcohol survey questions. Contemp Drug Prob. 1999;26:673–693. [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Rogers JD, Greenfield TK. Mode differences in reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm. In: Cynamon ML, Kulka RA, editors. Seventh Conference on Health Survey Research Methods [DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 01-1013] Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. pp. 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Latest approaches to preventing alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Alcohol Research and Health. 2000;24(1):42–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyaronga D, Greenfield TK, McDaniel PA. Drinking context and drinking problems among black, white and Hispanic men and women in the 1984, 1995 and 2005 U.S. National Alcohol Surveys. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(1):16–26. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Beattie M. Relationship and institutional pressure to enter treatment: differences by demographics, problem severity, and motivation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(3):428–436. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Weisner C. Factors associated with coercion in entering treatment for alcohol problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54(1):63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R. The U.S. general population’s experiences of responding to alcohol problems. Br J Addict. 1989;84:1291–1304. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Bondy SJ, Ferris J. Determinants of suggestions for alcohol treatment. Addiction. 1996;91(5):643–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9156432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Greenfield TK, Weisner C. People who might have liked you to drink less: changing responses to drinking by U.S. family members and friends, 1979–1990. Contemp Drug Prob. 1991;18(4):573–595. [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Matzger H, Weisner C. Sources of informal pressure on problematic drinkers to cut down or seek treatment. J Subst Use. 2004;9(6):280–295. [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Svikis D, D’Onofrio G, Kraemer K, Perl J. Challenges Applying Alcohol Brief Intervention in Diverse Practice Settings: Populations, Outcomes, and Costs. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(2):332–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Bond J. Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol ClinExp Res. 2007;31(1):48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speiglman R. Mandated AA attendance for recidivist drinking drivers: policy issues. Addiction. 1997;92(9):1133–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalay LB, Inn A, Doherty KT. Social influences: effects of the social environment on the use of alcohol and other drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 1996;31(3):343–373. doi: 10.3109/10826089609045816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Greenfield TK. Continuing trends in entry to treatment for alcohol treatment in the U.S. general population: 1984–1995. Berkeley, CA: Alcohol Research Group; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Schmidt L. The Community Epidemiology Laboratory: studying alcohol problems in community- and agency-based populations. Addiction. 1995;90(3):329–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9033293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]