Abstract

Antibodies, with their unmatched ability for selective binding to any target, are considered as potentially the most specific probes for imaging. Their clinical utility, however, has been limited chiefly due to their slow clearance from the circulation, longer retention in non-targeted tissues and the extensive optimization required for each antibody-tracer. The development of newer contrast agents, combined with improved conjugation strategies and novel engineered forms of antibodies (diabodies, minibodies, single chain variable fragments, and nanobodies), have triggered a new wave of antibody-based imaging approaches. Apart from their conventional use with nuclear imaging probes, antibodies and their modified forms are increasingly being employed with non-radioisotopic contrast agents (MRI and ultrasound) as well as newer imaging modalities, such as quantum dots, near infra red (NIR) probes, nanoshells and surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). The review article provides new developments in the usage of antibodies and their modified forms in conjunction with probes of various imaging modalities such as nuclear imaging, optical imaging, ultrasound, MRI, SERS and nanoshells in preclinical and clinical studies on the diagnosis, prognosis and therapeutic responses of cancer.

Keywords: Antibody, imaging, SPECT, tumor, optical

1. Introduction

Non-invasive in vivo tumor imaging is one of the most active research fields used to visualize the target molecules on altered cells by virtue of target-probe interaction at the molecular level. For this, several different imaging modalities [e.g., nuclear imaging, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance spectroscopy, computed tomography (CT), ultrasound (US), bioluminescence, and fluorescence imaging (optical imaging)] are being used for visualization of tumors [1]. The success of an imaging modality depends on optimal combination of various factors (summarized in Fig. 1). Along with the issues of biocompatibility, toxicity and probe stability, the major challenge associated with the use of various imaging modalities is to achieve a high contrast signal over nearby normal tissues. To address this issue, radioisotope, magnetic, or optically active imaging probes are coupled with tumor targeting molecules, including antibodies, peptides, small molecule ligands and synthetic graft copolymers. Due to their exquisite specificity toward cognate antigens, antibodies (Abs) are useful agents for both cancer diagnosis and therapy. Earlier, the utility of antibodies for imaging was limited by their large size (150 kDa), as the intact immunoglobulins remain in circulation for longer period (few days to weeks) and take longer time to optimally accrete in tumors (1–2 days) [5]. Advancement in antibody engineering has led to the development of various forms of antibodies i.e. monovalent fragments [variable fragments Fv, single chain variable fragments (scFv)], bivalent or bispecific diabodies and minibodies (Fig. 2). Further, because of improvements in knowledge of modulating their immunogenicity, behavior in circulation, pharmacokinetics, and conjugation chemistry with various scanning agents like radionuclides, fluorescent and bioluminescent tracers, and various contrast enhancing agents, antibodies and their modified forms have emerged as preferred agents to target tumor antigens [6]. Several antibodies have been approved by the FDA for imaging and immunotherapy (reviewed in [2]). However, to date, the arena of antibody based imaging is predominantly occupied by radiolabeled antibodies. Keeping in view the widespread employment of intact antibodies and promising prospects of engineered antibody fragments, the present review discusses the increasing usage of antibodies and their fragments with various imaging modalities in cancer.

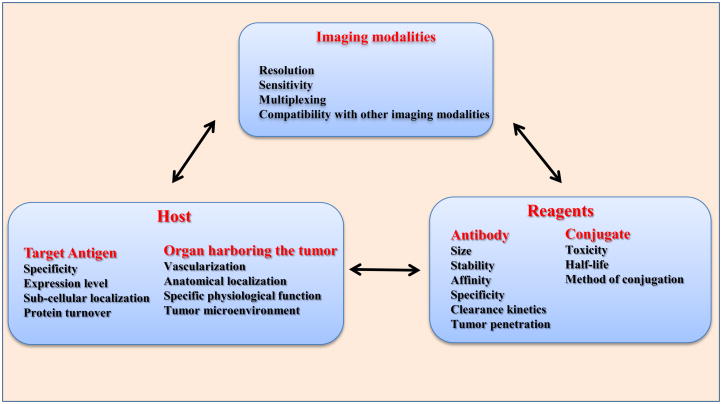

Figure 1. Schematic representation of factors associated with the development of antibody-mediated oncologic imaging and controlling success.

The success of imaging is dictated by the interplay between the modality used for imaging, properties of tracer and targeting agent, as well as the location and nature of the targeted antigen. The diagnostic efficiency of the imaging probe depends upon the optimal combination of modality, the targeting agent as well as the environment of the targeted organ.

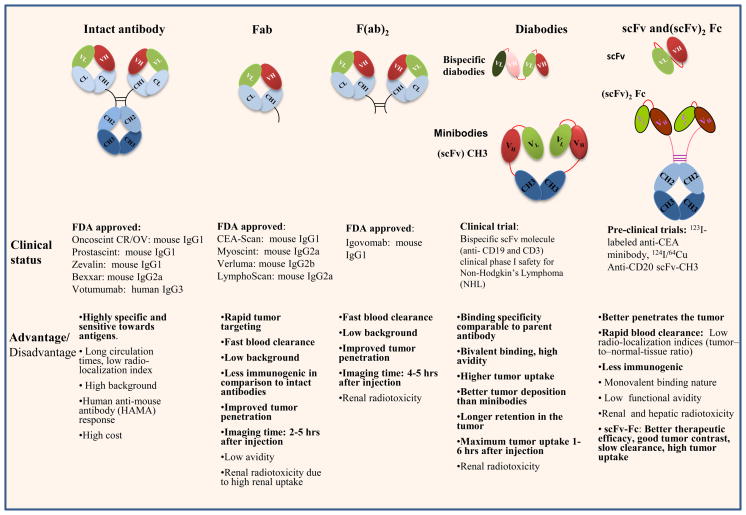

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of the design, status and characteristics of various antibody forms being employed for targeted imaging and therapeutic applications in cancer.

The list of therapeutic and diagnostic antibodies used in clinical (FDA approved) and pre-clinical studies along with their advantages (bold) and disadvantages are summarized. Intact antibody (Ab) contains two antigen-binding sites in the Fab domain and the effector functions such as complement activation and macrophage binding are mediated by the Fc domain. The variable regions of the heavy and light chains (VH and VL respectively) are involved in specific recognition of cognate antigen. Smaller antibody fragments that retain specific antigen binding are prepared enzymatically [entire F(ab)2 or individual Fabs], or using recombinant technology by connecting the variable regions of the heavy and light chains with a peptide linker, thus forming a single chain variable fragment (scFv). Two scFv molecules can be covalently linked via a peptide linker to form a divalent scFv, or they can associate noncovalently to form a diabody. Tetravalent scFv results from the noncovalent association of two divalent scFvs, whereas the minibody is a fusion of scFv with the CH3 for an increased serum half-life. In the figure, each oval represents an immunoglobulin folding domain. The polypeptide linker of the scFv is shown by a red connecting ribbon, while disulfide bonds are represented as black lines. VL indicates a variable domain light chain; VH, variable domain heavy chain; CL, constant domain light chain; CH, constant domain heavy chain; Fc, Fc fusion; IgG, immunoglobulin G; F(ab)2, dimeric antigen binding fragment; and Fab, antigen binding fragment.

2. Nuclear Imaging

Nuclear imaging is the most common non-invasive diagnostic modality for cancer. It employs radiolabeled tracers that are concentrated in cancerous tissue generating the radioactive signal for visualization of tumors. Depending on the type of radioactive emissions, nuclear imaging is broadly classified into two types: single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET). Due to their ability to specifically target their cognate antigens, antibodies and their modified forms have carved a niche in nuclear imaging with both SPECT and PET.

2.1. Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT)

SPECT employs absorptive collimation wherein information from single photons is used to construct a tomographic image [3]. SPECT has found many applications in conventional nuclear medicine due to its ability to remove overlying structures, which may obscure the abnormality in gamma camera imaging, thereby improving the contrast.

Out of various SPECT radionuclides [Technetium-99m (99mTc), Indium-111(111In), Iodine-123(123I), Iodine-125 (125I), Gallium-67 (67Ga), and Lutetium-177 (177Lu)], 99mTc and 111In are the most commonly used isotopes for SPECT and among the two; 99mTc is a more versatile radionuclide because of its ease of labeling, favorable half-life, cost effectiveness and negligible particulate emissions. Five antibodies, among the FDA approved diagnostics being employed for human imaging, are 99mTc- or 111In-labeled [4]. A list of antibody conjugates tested for SPECT imaging is summarized in Table I. A number of antibodies have been approved by FDA for SPECT based imaging in the past, however among them i) Oncoscint was withdrawn from the market in 2002 due to comparatively better efficacy of fluorine-18 deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) (having sensitivity similar or higher than the oncoscint scan), ii) Verluma (murine antibody recognizing 40 kDa glycoprotein antigen present on surface of small cell lung cancer cells) license was terminated by DuPont MERCK in 1999 due to its limited efficacy (failed to image tumors in various organs in 23% of patients). Similarly, commercial usage of Arcitumomab (CEA-SCAN), an antibody fragment reactive against carcinoembyronic antigen (CEA), for the detection of recurrent and/or metastatic colorectal cancer [5] is limited due to similar efficacy of FDG-PET in detecting local tumor and comparatively better efficacy in detecting distant metastasis.

Table I.

Immunoconjugates used for SPECT imaging of human malignant tumors.

| Name | Antibody | Targeted antigen | Isotope | Indication for use | Clinical Status/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA SCAN$ | Fab fragment of murine mAb IMMU-4 | CEA | 99mTc | Primary and recurrent colorectal carcinoma | FDA approved (1996) |

| HUMASPECT-TC$ | Human IgG3Kappa | CTAA16.88, cytokeratin polypeptide | 99mTc | Colorectal, breast, Prostate, lung, ovarian and pancreatic cancer | FDA approved (1998) |

| ONCOSCINT$ | Murine mAb B72.3 | TAG-72 | 111In | Primary and recurrent colorectal carcinoma, recurrent ovarian cancer | FDA approved (1992) |

| VERLUMA$ | Fab fragment of murine mAb NR-LU-10 | CEA | 99mTc | Small cell lung cancer | FDA approved (1996) |

| PROSTASCINT | Murine mAb 7E11- C5.3 | PSMA | 111In | Metastatic prostate Cancer | FDA approved (1996) |

| TRASTUZUMAB* | Humanized mAb | HER2 | 111In | Metastatic breast cancer | [110] |

| RITUXIMAB* | Chimeric 2 mAb | CD20 | 99mTc | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | [111] |

| L19# | (scFv)2 | EDB-fibronectin | 123I | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Phase1/II [112] |

| IORC5# | Murine mAb | CEA | 99mTc | Anal and colorectal cancer | Phase1/II [113] |

| h-R3# | Humanized mAb | EGFR | 99mTc | Epithelial derived tumors | Phase1/II [114] |

Antibodies and antibody fragments approved for radioimmuno-therapies but studies are going on to assess their imaging potential,

Antibodies and their fragments used for pre-clinical studies of human tumors.

No longer available

[111]In-labeled Prostascint [Capromab Pendetide- murine mAb, directed against Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA)] is currently in clinical use for the diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer [6, 7]. The sensitivity, specificity, positive (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) for [111]In-labeled prostascint SPECT-CT was found to be comparable to biopsy for detecting seminal vesicle invasion (SVI), but overall SPECT-CT was found to have limited ability in detecting SVI. SPECT was rarely used for quantitative imaging, primarily due to its poor photon statistic and difficulties in applying physical correction [8]. Seo et al. used [111]In-labeled Prostascint in combination with CT to evaluate a new SPECT based quantitative grading system for prostate cancer detection [9]. In this study, a new correction factor was introduced to account for photon attenuation, scatter, and geometric blurring caused by radionuclide collimators. A significant correlation was observed between antibody uptake by the malignant cells and the Gleason score of the tumor.

Trastuzumab, a humanized mouse monoclonal antibody reactive with Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2), also known as ErbB2, c-erbB2 or HER2/neu, has been approved for immunotherapy of metastatic breast cancer. HER2 is a 185 kDa protein with an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain and an extracellular ligand binding domain. Under normal condition, it is expressed at basal level in normal thyroid, placenta, trachea, kidney, prostate, and mammary gland [10]. Its overexpression, primarily due to gene amplification, is observed in a number of epithelial malignancies including breast, ovarian, gastric, prostate and other cancers. Among breast cancer patients, HER2 is overexpressed (10–100 times above normal levels) in 13–23% of tumors and is an important therapeutic target. Trastuzumab promotes cancer cell apoptosis by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [11]. However, the therapeutic efficacy of trastuzumab is compromised by cardiotoxicity. In order to develop a non-invasive method for evaluating the efficacy of trastuzumab, and at the same time avoiding patients prone to developing trastuzumab associated cardiotoxicity, Lub-De Hooge et al. studied the stability and biodistribution pattern of [111]In-labeled trastuzumab in HER2 receptor-positive and -negative tumor-bearing athymic mice. The trastuzumab was conjugated to chelator diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid dianhydride (DTPA) using cyclic anhydride method followed by radiolabeling with 111InCl3. The [111]In-labeled trastuzumab showed high stability as well as a pronounced uptake in HER2-positive tumors compared to HER2-negative tumors at 5 hrs after injection. The clear difference in uptake was visible by immunoscintigraphy even after 3 days of injection [12]. In a clinical study, [111]In-labeled trastuzumab successfully detected new tumor lesions in 13 out of 15 patients. The primary goal of the study was to evaluate the ability of [111]In-labeled trastuzumab scintigraphy to predict cardiotoxicity in metastatic breast cancer patients [13].

In addition to these clinically approved antibodies, radioimmunoscintigraphy with 99mTc labeled-SM3 antibody in patients with ovarian cancers was shown to be useful in the evaluation and management of gynecologic malignancies [14]. However, low tumor to background ratio, poor tumor uptake and heterogeneity of expression of the antigen were the major drawbacks. In order to circumvent these issues, Biassoni et al. applied a change detection algorithm for detecting small changes that occurred in [99m]Tc-labeled SM3 uptake over time for evaluating the metastatic involvement of axillary lymph nodes in patients with breast cancer. For this, statistical pixel by pixel comparisons were made between the 10 min and the 22 hrs images. The image analysis of 29 axillary lymph node regions studied showed 3 out of 10 true positives and 18 out of 19 true negatives leading to a sensitivity of 30%, specificity of 95% and accuracy of 72% [15]. Further, extending their study, Al-Yasi et al. used a 99mTc radiolabeled anti-Polymorphic Epithelial Mucin (PEM) humanized monoclonal antibody (human milk fat globule 1), hHMFG1, for assessing the status of axillary nodes. Using 99mTc humanized hHMFG1 with change detection analysis they were able to detect 13 out of 14 true negatives, however, imaging suffered from poor sensitivity with several false negative results [16]. In another study, [99m]Tc -labeled-IgG1κ murine mAb PR1A3 (recognizing CEA) was used successfully to image colorectal tumors. The antibody binds strongly to both well and poorly-differentiated colorectal adenocarcinomas. Radioimmunoscintigraphy using 99mTc PR1A3 was beneficial in the management of a sub-group of colorectal cancer patients [17, 18]. PR1A3 was used in radioimmunoguided surgery (RIGS) to detect and remove occult metastatic deposits in patients with colorectal cancer [19]. Further, for improving the avidity and affinity, biparatopic antibody was made by chemically cross-linking reduced Fab fragments of two anti-CEA antibodies, PR1A3 and T84.66 that are reactive against two different non-overlapping epitopes. Pharmacokinetic analyses revealed that the biological half-life of biparatopic Ab was very similar to parental Fab fragments and four times shorter than that of the intact parental antibodies. Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of more than 90% was observed for detecting colorectal tumors in mice pretreated with biparatopic antibodies [20]. Further, [125]I-labeled anti-CEA biparatopic antibodies were able to detect primary and metastatic tumors with an accuracy of 100% and 88.7%, respectively, in colon cancer patients. A false positive rate of 9.4% was observed, which was attributed to trapping of radionuclides in the lymphatic tissue [21].

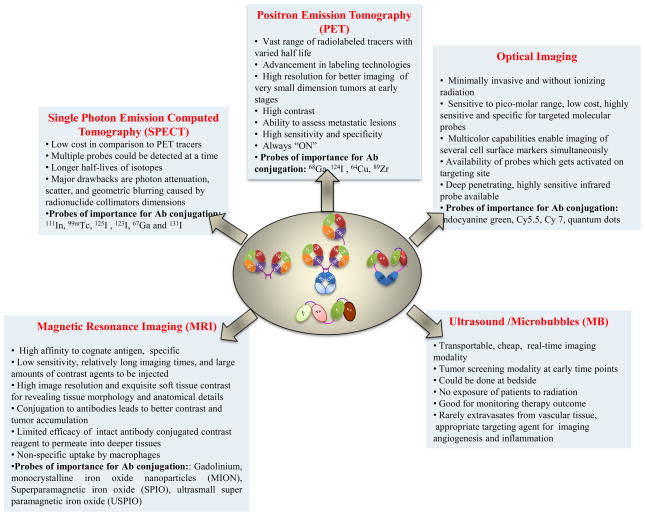

With these applications in SPECT imaging, radiolabeled antibodies are useful adjuncts in clinical decision-making algorithms for tumor imaging and therapy based on SPECT. Although SPECT is 10 to 100 times less sensitive than PET due to lower photon statistic, it is quite useful owing to their lower cost than PET and the possibility of using multiple probes simultaneously (Fig. 3). The technique does have certain disadvantages, including photon attenuation, scatter, and geometric blurring caused by radionuclide collimators.

Figure 3. Salient features of various imaging modalities used in conjunction with intact antibodies or their engineered forms.

Apart from nuclear (PET and SPECT) and optical imaging, the usage of antibodies is increasing in ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging for targeting the contrast agents to tumor lesions to improve image quality.

2.2. Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a non-invasive imaging modality that allows quantitative evaluation of the biological processes in vivo. It is based on the emission of positrons from nuclear decay of an intravenously injected radioisotope. The PET scanner then uses positron annihilation to determine their spatial location. Lately, PET is being used in combination with MRI and CT for precise imaging of the anatomical sites with heightened metabolic activities. Although 18F (fluorine-18) is the most common PET isotope, the others being used include 124I, 89Zr, 64Cu, 94mTc, 76Br, 89Zr and 68Ga [22]. The 10-fold higher sensitivity of PET compared to conventional SPECT scanners allows for the detection of tracer isotopes at a much lower concentration (1011–1012 mol/L). This together with its higher resolution (3–9 mm3) permits imaging of very small tumors [3]. Among PET isotopes, 18F has a half-life of 110 min, a feature that has allowed wide spread use of this isotope for clinical imaging. As an analogue of glucose, 18F labeled deoxygluocose (18FDG) enters actively dividing cells through membrane glucose transporters (GLUTs). GLUT expression increases significantly in cancer cells. This results in significant uptake of FDG by these cells, thus permitting imaging of the tumor with high sensitivity. FDG-PET has thus gained wide-spread acceptance as a routine imaging modality for the diagnosis, staging and management of several malignant lesions. While FDG-PET allows quantitative measurement of a cellular metabolic activity, its results have to be interpreted with great caution, as the rate of glucose uptake can vary from patient to patient, both under normal conditions and malignancies. Further, 18F-FDG uptake is also accelerated during inflammatory processes like infections, granulomas and abscesses, hence the presence of a concomitant inflammation can lead to false positive results [23]. Further, FDG accumulates in the brain and myocardium both of which rely on glycolytic metabolism during nonfasting state. Because FDG is excreted in the urine, strong signal is also observed in the intrarenal collecting systems, and bladder. Due to the possibility of false positive results, PET is currently being used in combination with CT and MRI. With the advancement of conjugation chemistry and better availability of longer half-life radioisotopes like 124 I (t1/2: 100.2 hrs) and 89Zr (t1/2: 78.4 hrs), antibody based targeted PET imaging, i.e. immunoPET, has emerged as a promising alternative to the conventional metabolic PET. Unlike conventional PET, the signal from immunoPET depends upon the presence of a specific antigenic target. Hence, immunoPET exhibits greater specificity and can also be used to image tumors that exhibit low metabolic activity.

2.2.1. ImmunoPET

As a novel modification of conventional PET, immunoPET combines the high resolution and quantitative aspects of PET with the high specificity and selectivity of antibodies. Some of the PET isotopes suitable for use with antibodies are 73Se (t1/2: 7.1 hrs), 76Br (t1/2: 16.1 hrs), 64Cu (t1/2: 12.7 hrs), 89Zr (t1/2: 3.27 days), and 124 I (t1/2: 4.18 days). Although 18F is most commonly used as a metabolic tracer, its use in immunoPET is limited due to its very short half-life (110 min) for antibody targeted imaging. However recently, an anti-CEA diabody labeled with 18F using the N-succinimidyl-4-18F-fluorobenzoate method showed promising results [24]. The 18F labeled diabody retained its immunoreactivity and yet showed a rapid rate of clearance together with high tumor uptake in comparison to background absorption in non-tumor sites. Better contrast immuno-PET images of LS174T colon tumors were obtained 1 hr after injection of the radioconjugate and only background accumulation was noted in antigen negative glioma tumor xenografts. However, this contrast was only 2.7% injected dose per gram of tumor tissue (ID/g) along with 2.0% ID/g in the blood and higher uptake in the other major organs [24]. Since it usually takes 4–6 hrs to develop a favorable tumor to tissue ratio, the use of 18F is limited with antibodies, 18F usage is increasing with guided imaging of tumor xenografts as discussed later. Table II gives a list of some of the important PET immunoconjugates evaluated in various pre-clinical studies.

Table II.

Important PET immunoconjugates being evaluated in various preclinical and clinical studies.

| Targeted antigen (Antibody details) | Isotope label used | Model used for the study | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonic anhydrase IX (Chimeric G250) | 124I | Renal cell cancer | [27] |

| V6 domain of CD44 (mAb U36) | 89Zr | Head and neck squamous cell cancer | [35] |

| HER2 (Trastuzumab) | 89Zr | Breast cancer | [13] |

| CEA (Minibody, Diabody, scFv-Fc)* | 124I | Colon cancer | [25] |

| HER2 (Diabody) | 124I | Ovarian cancer | [45] |

| CD20 (Diabodies scFv-1, scFv-3, scFv-5, scFv with different linker lengths)* | 124I | B cell lymphoma | [41] |

| CEA (Diabody-T84.66)* | 18F | Colon cancer | [24] |

| CEA (Minibody)* | 64Cu | Colon cancer | [39] |

| HER2 (Minibody)* | 64Cu | Breast cancer | [115] |

| Pre-targeting imaging Probes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted antigen | Pre-targeting agent | Targeting agent | Model used for the study | Reference |

| CEA* | Anti-CEA and anti-hapten Bispecific antibody | 18F or 68Ga labeled hapten peptide | LS174T human Colonic tumor xenografts | [44] |

| CEA* | Anti-CEA and anti-HSG (peptide histamine-succinyl- glycine) recombinant bispecific-mAb | 124I-labeled peptide | LS174T human colonic tumors | [116] |

| MUC1 | Anti-MUC1 mAb (12H12) and F(ab’) fragments of an anti-gallium (Ga) chelate mAb | 68Ga-Chelate | Breast cancer | [42] |

| Ep-CAM* | mAb-streptavidin conjugate NR-LU-10/SA | 64Cu-DOTA -biotin | SW1222 human colorectal carcinoma xenografts | [117] |

Positron emitter 124I due to its long half life (4.18 d) that is compatible with the pharmacokinetics of antibodies and the ease of labeling has been extensively investigated for immuno-PET. Sunderesan et al. observed antigen specific PET imaging of colon tumor xenografts using [124]I-labeled with anti-CEA Ab fragments [25]. These fragments (minibodies and diabodies) showed rapid blood clearance and specific retention in tumors, and importantly yielded PET images with good contrast. Head-on comparison of immuno-PET to metabolic FDG-PET in this study showed superiority of the immuno-PET imaging method [25].

The pharmacokinetics of antibody could be improved by either reducing its size or altering the Fc receptor-binding domain. Kenanova et al. modulated the pharmacokinetics of anti-CEA antibody fragments, by generating mutated forms of the neonatal Fc receptor binding sites of the anti-CEA antibody fragments [26]. These scFv-Fc forms of chimeric anti-CEA antibodies, when labeled with 124I showed improved blood clearance and provided better contrast immuno-PET images. Divgi et al. used [124]I-labeled chimeric antibody G250 reactive against carbonic anhydrase-IX, which is overexpressed in clear-cell renal carcinomas. Immuno-PET with this conjugate successfully detected 15 out of 16 renal cell carcinomas in patients with renal tumors [27]. L19 antibody directed against the extracellular domain of fibronectin was selected from the phage library and its various forms, i.e. dimeric scFv [(scFv)2], a human bivalent “small immunoprotein” (SIP, ~80 kDa), and a complete human IgG1 [28]. Biodistribution studies in mice showed that [131] I-labeled L19-SIP has the most favorable therapeutic index. Considering these studies, Tijink et al. (2009) tested the efficacy of [124]I-labeled antibody (L19) for imaging angiogenesis as well as a scouting procedure for judging the efficacy of this conjugate for RIT [29]. Studies using [124]I -L19-SIP conjugate showed high and selective tumor targeting, resulting in tumor to blood ratios ranging from 6.0 at 24 hrs to 45.9 at 72 hrs post-injection. While normal tissue accumulation of [124]I-labeled-L19-SIP was significantly lower, clear visualization of tumors as small as ~50 mm3 was observed [29]. The major drawback of 124I for PET imaging is the release of high-energy positrons and considerable expense. Moreover, [124]I-labeled antibodies upon internalization undergo degradation which causes rapid clearance of the radionuclides from the target, resulting in poor contrast. However, the interest in 124[I] has renewed in recent years due to the better availability of the radioisotope.

Zirconium-89 (89Zr), a transition metal is a useful PET-imaging radionuclide due to its residualizing capacity and a longer half life (3.3 d) that is compatible to pharmacokinetics of intact antibodies. Further, high yield, high radionuclide purity, and low production costs has generated interest for evaluating the potential of 89Zr [30]. Utility of [89]Zr-labeled mAbs as an imaging procedure for preceding RIT has been evaluated in several studies [22, 30, 31]. In one of the earliest studies, 89Zr was labeled with mAb U36 recognizing the v6 domain of CD44, a tumor antigen overexpressed in head and neck tumors. This radioimmunoconjugate was used in preclinical models to confirm tumor targeting and estimate the dose deposition to tumor and normal tissues prior to RIT with [90]Y-labeled mAbs [32]. [89]Zr-labeled mAb was stable in vivo and provided better spatial resolution than that obtained with 18F glucose PET. Recently, Vosjan et al. showed that facile labeling of 89Zr to mAb could be done in a period of 2.5 hrs using bifunctional chelator p-isothiocyanatobenzyl-desferrioxamine (Df-Bz-NCS) [33]. 89Zr-U36 was used for detecting lymph node metastasis in head and neck cancer patients [2, 34, 35]. This conjugate visualized all primary tumors; additionally 18 out of 25 tumor-containing neck levels were also detected. Sensitivity and specificity of [89]Zr–labeled cU36 immunoPET imaging (85% sensitive and 100% specific) was equivalent to CT-MRI (77% sensitive, 100% specific). Better delineation of tumor and lymph node metastasis was observed at later time points due to a high tumor to non-target tissue ratio. However, the conjugate failed to detect micrometastasis in lymph nodes containing just a small proportion of tumor tissue [34]. Dijkers et al. developed clinical-grade [89]Zr-labeled trastuzumab for clinical HER2/neu immunoPET scintigraphy [36]. A comparative biodistribution study showed a higher level of [89]Zr-trastuzumab in HER2/neu-positive tumors than in HER2/neu-negative tumors. The radioconjugate was stable up to 7 days. The conjugate allowed PET imaging of the majority of the known lesions and some that had been undetected earlier in breast cancer patients with metastasis. The study revealed that trastuzumab-naive patients required a 50 mg dose of [89]Zr-labeled-trastuzumab, and patients already on trastuzumab treatment required only a 10 mg dose of the conjugate [13]. In renal cell carcinoma, in vivo biodistribution of [89]Zr-labeled mAb cG250 was identical to that of [111]In-DTPA-cG250 [37]. Comparative PET imaging of c-Met receptor using DN30 antibody in GTL16 (human gastric cancer cell line) tumor-bearing mice was performed to assess the imaging and therapeutic efficacy of two long-lived radioisotopes i.e. 89Zr and 124I. For 89Zr radiolabeling, lysine residues of mAb DN30 was coupled to active form of bifunctional metal chelate tetrafluorophenol N-succinylated desferal followed by radiolabeling with 89Zr while 131I (used as substitute of 124I to facilitate simultaneous counting in biodistribution studies) labeled DN30 was prepared using iodogen method. DN30 antibody has the unique ability to get internalized and during the study residualizing isotope 89Zr showed much better tumor to non-tumor tissue ratio in comparison to 124I while other tissues including blood had an almost similar pattern. Residualizing isotope 89Zr in combination with DN30 performed much better than 124I which metabolizes quickly and is subsequently released from the tumor cell due to low-molecular mass metabolic product [38]. 89Zr-immunoPET with a longer half life, better tumor retention and quantitative imaging qualities, holds promise for the detection of tumors and planning of Ab-based therapies.

Copper 64 (64Cu), with its long half-life and decay characteristics, is another positron emitting radionuclide that has been exploited for radioimmunoimaging. Initially, a macrocyclic chelating agent 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N′,N″, N‴-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) was used to chelate 64Cu to label a high affinity anti-CEA minibody [39]. This radiolabeled anti-CEA minibody (80 kDa) cleared rapidly from the circulation and exhibited moderate tumor uptake during serial imaging of antigen positive tumors using the microPET scanner. In another study, scFv-Fc double mutant hu4D5v8 (a series of mutations were made in the Fc region which alter the interaction of the Fc region with the neonatal receptor, of all the mutations H310A and H435Q lowered the interaction with neonatal Fc receptor and reduced non-specific reactivity of scFv-Fc variant with kidney) derived from the anti-HER2 antibody, trastuzumab was constructed and radiolabeled with 64Cu using DOTA. This mutant was constructed to optimize tumor uptake and minimize non-specific uptake by normal tissues and it was evaluated in nude mice bearing HER2 positive tumors. Quantitative microPET using 64Cu-DOTA labeled hu4D5v8 showed improved tumor uptake and reduced uptake by kidneys [40, 41].

68Ga produced by generator has a half-life of 68 min with positron emission which is shorter than that of the 18F, even though it provides a cost-effective alternative for sites without a cyclotron. An immunoscintigraphy study used a three-step pre-targeting technique utilizing [68]Ga-labeled bispecific antibody (BS-mAb), an anti-MUC1/anti-Ga chelate BS-mAb to image breast cancer patients. The strategy in this study was to first localize the anti-MUC1/anti-Ga chelate Ab to the tumor and then saturate the anti-Ga chelate binding sites of the BS-mAb present in circulation with the blocking agent. Tumors were visualized using 68Ga-chelate, injected 1 hr after the administration of the blocking agent. During this study, they visualized 14 out of 17 known lesions, with an average lesion size of 25 mm in size. There were no false positives in the study but three false negatives were identified. The standard uptake value for the tumor at 1 hr was two, which might be due to the fast tumor kinetics and non-specific distribution of the shed antigen MUC1 [42]. Smith-Jones et al. used a [68]Ga-labeled F(ab) fragment of the anti-HER2 antibody for quantitative PET imaging of HER2 expressing breast tumor xenografts and observed signal intensity in the tumors proportional to the levels of antigen expression [43]. This radioimmunoconjugate was used for assessing the therapy response after treatment of tumors with 17-allylaminogeldanamycin. This drug is an Hsp90 inhibitor and causes HER2 degradation. Thus [68]Ga-labeled-anti-HER2 F(ab) clearly demonstrated quantitative imaging of the pharmacodynamic effects of drugs. Further, in a pre-targeting study, Schoffelen et al. compared the efficacy of 18F and 68Ga short lived isotopes for imaging LS174T human colonic tumors expressing CEA and compared it to conventional 18FDG. Animals were first injected with anti-CEA and anti-hapten bispecific mAb followed by intravenous injection of 18F or [68]Ga-labeled hapten peptide. Almost a 10-fold higher uptake of conjugate was observed in the tumor in comparison to its uptake in the inflammatory region. In contrast, 18FDG showed only a two-fold higher uptake in the tumor. Bispecific antibody used during the study showed higher retention in the tumor and a very low circulation time [44]. Pre-targeted immuoPET is a promising technology for detecting tumors with high sensitivity and specificity with short-lived isotopes.

ImmunoPET has recently been explored in combination with other imaging modalities like CT and near infra red (NIR) imaging. Robinson et al. assessed immunoPET imaging of HER2 positive tumors using [124]I-labeled anti-HER2 diabody on a clinical PET/CT scanner [45]. Good contrast images of HER2 positive SKOV3 ovarian tumors of clinically relevant size (0.11–0.86 g) were observed. Antigen dependent imaging of mouse tumor xenografts was observed with an increase in tumor signal at the end of 48 hrs when compared with antigen negative xenografts. In addition to ImmunoPET, developments in the fields of biomedical engineering have led to the design of dual-modality imaging systems that have a CT scanner (X-ray tube and detector) and a radionuclide detector (PET or SPECT) mounted on a single gantry with a common patient table for X-ray and radionuclide imaging [46]. This allows the CT and radionuclide images to be acquired with a consistent scanner geometry, with the body in the same position, and with minimal delay between the two acquisitions. After both sets of images are acquired and reconstructed, image registration software is used to fuse the X-ray and radionuclide images and the fused images are analyzed. Paudyal et al. designed an anti-CD20 antibody with a double functional probe, i.e. 64Cu and Alexa Flour 750. PET and NIR imaging using 64Cu-DOTA-NuB2-Alexa Fluor 750 was carried out in CD20 positive Raji lymphoma-bearing mice [47]. The dual modality probe exhibited in vivo stability and a strong correlation between PET and NIR images. The development of dual-labeled probes offers a convenient and direct approach for imaging tumors with greater certainty. Hence, these dual imaging systems act complimentary to each other by giving anatomical detail and functional content.

2.3 Nanobodies and Affibodies in Nuclear Imaging

Both nanobodies and affibodies are being tested for improving nuclear imaging due to their small size and high affinity for targeting agents. In order to provide better contrast and early imaging agents for HER2 positive cancers, Vaneycken et al. generated nanobodies against HER2 by immunizing a dromedary (Arabian camel) with HER2-Fc recombinant fusion protein followed by cloning and display on phages [48]. Nanobodies specific to HER2 were selected by biopanning on immobilized HER2-Fc protein or on adherent formalin-fixed HER2-positive cells. The nanobodies, 2Rs15d and 1R136d, were selected on the basis of stability and ability to interact specifically with HER2 recombinant protein and HER2-expressing cells in ELISA, surface plasmon resonance, flow cytometry, and radioligand binding with low nanomolar affinities. [99m]Tc-labeled nanobodies 2Rs15d and 1R136d revealed fast clearance (1 hr) from blood and specific uptake in SKOV3 bearing ovarian xenografts. However, high kidney uptake and an intense activity in the bladder were also observed, which might be due to renal-filtration of nanobodies. Similarly, Gainkam et al. used [99m]Tc-labeled anti-EGFR nanobodies to image sub-cutaneous A431 (lung cancer) xenograft bearing animals [49]. Pinhole SPECT and micro-CT imaging showed specific uptake of [99m]Tc-labeled anti-EGFR nanobodies (7C12 and 7D12) in A431 xenografts after 1 hr of conjugate administration. The short blood half-life (within 10 min) of nanobodies allowed early imaging of tumors with high contrast after 1 hr of injection, however, non-specific uptake in kidney and bladder is the limitation of nanobodies for imaging lesions in the area of the kidneys and bladder.

Apart from various forms of antibodies, affibodies have received significant attention as tumor targeting probes for imaging. These are small proteins (58 amino acids) derived from IgG binding domain of staphylococcus protein A. Due to their small size (four times smaller than scFv and 20 times smaller than mAbs) and high affinity for targeting agent, they are considered most promising potential probes for imaging. Hoppman et al. evaluated the efficacy of [64]Cu and [111]In-labeled anti-HER2 affibody molecules in SKOV3 tumor-bearing nude mice. Both rapid as well as high tumor uptake values (>14% ID/g at 24 and 48 hr) were observed in HER2 overexpressing SKOV3 tumors. Although rapid clearance from kidney was observed, high liver accumulation was the biggest drawback [50]. Recently, Kramer-Marek et al. used anti-HER2 affibodies [18]F-FBEM-ZHER2:342 prepared using site-specific labeling techniques for in vivo imaging of HER2-positive SKOV3 tumors [51]. Biodistribution and microPET imaging studies revealed rapid, high and specific accumulation in HER2 over-expressing SKOV3 tumor. The tumor to background ratio of 7.5 was observed after 1 hr post-injection while it increased to 27 after 4 hrs. Apart from tumor, non-specific uptake was observed in kidneys and bone. In case of kidney, the radioactivity decreased from 14% ID/g at 1hr to 1.5% ID/g at 4 hrs post-injection. Both high selectivity and affinity of affibodies are promising attributes towards better imaging, however rapid clearance from non-specific compartments (liver and kidneys) need to be optimized for enabling high contrast imaging shortly after administration.

Looking at various clinical and preclinical studies on immunoPET, there is no doubt regarding promising aspects of immuno-PET for imaging tumor lesion, however, it needs further improvements including: i) improved methods to radiolabel antibodies and antibody fragments with PET isotopes, ii) newer radioisotopes with longer half-lives, iii) genetically engineered antibody fragments with better pharmacokinetics, i.e. shorter half life, fast blood and whole body clearance and better retention in tumor tissues [2] for conjugation with short-lived radioisotopes and, iv) isotopes with residualizing capacity, i.e. isotope which are retained within the target cell after internalization and intracellular degradation of the radioconjugate.

3. Upcoming Imaging Modalities

3.1 Optical Imaging

In addition to nuclear imaging, the use of antibodies is being increasingly explored in the field of biomedical optical imaging that mainly includes fluorescence or bioluminescence based imaging probes. Due to their high sensitivity, specificity, low cost, portability of imaging instruments and absence of ionizing radiations, optical imaging modalities have emerged as a preferable alternative over radioisotope-based imaging. Further, with the advancements made in optical devices, fluorochrome design and conjugation methods, optical imaging modalities have become more practical, at least in the experimental settings. In fluorescence imaging, cells are labeled with dyes or proteins that emit light of a limited spectrum when excited by different wavelengths of light. Bioluminescence methods use an enzymatic reaction between a luciferase enzyme and its substrate, luciferin, to produce photons which are converted to electrons by a cooled charged couple detector (CCD), which allows the detection of visible light through near-infrared light signals. Fluorescent molecules like green fluorescent protein (GFP) and red fluorescent protein (RFP) are used to observe the localization of proteins within a cell, to label specific proteins, or to monitor the production of a gene product [52]. For bioluminescence imaging, the bioluminescence reporter firefly luciferase (FL) and renilla luciferase (RL) are used. For assessment of targeted optical imaging, a fusion protein was constructed using diabody antibody fragment recognizing the CEA and RL [53]. This probe specifically targeted antigen positive xenografts within a tumor which was further confirmed using [124]I-labeled diabody-RL fusion protein. A radiolabeled probe showed biodistribution similar to an optical probe. In another set of studies, rhoadamine green conjugated anti-HER2 antibody herceptin showed a low signal when unbound, while it showed a comparatively high signal when bound and internalized within HER2+ cells in the murine model of lung metastasis. Herceptin-RhodG complex was able to detect HER2 positive tumors with high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (96.2%) [54]. One of the major stumbling blocks for widespread use of optical imaging during the initial days was their always ON property which caused a high target to background ratio. However, this issue is circumvented through on-site activation of the fluorescent agent at the target site through target-specific enzymatic activation or removal of a quencher or by the use of a photon-induced, electron transfer-based fluorophore. Initially, tumor-specific enzymes Cathepsin D and MMP-2 were used to specifically activate the fluorescence probe Prosense 680 at the tumor site [55]. The major problem with these probes was the non-specific activation at the non-tumor sites, resulting in a loss of specificity [56, 57]. An improvement over this strategy came with fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) in which a peptide quencher was associated with the fluorophore. Specific uptake of these probes followed by removal of the quencher in lysosomes of the target cells resulted in an intense signal at a specific site. About a 10-fold increase in signal intensity has been observed with ON target photoactivable probes, causing a much higher target to background ratio. Ogawa et al. compared the specific targeting efficiency of a FRET based probe, i.e. TAMRA (fluorophore)-QSY7 (quencher) pair in conjunction with the specific targeting agent avidin (targets D-galactose receptor) or trastuzumab. TAMRA does not fluoresce when present in close proximity to its quencher QSY7 [58]. The removal of QSY7 from TAMRA in lysosomes resulted in bright fluorescent intracellular dots in the target cell. Surprisingly, there was a low intensity fluorescence arising from Traz-TM-Q7 on the surface of HER2+ cells. The reason for activation of the molecule at the cell surface was uncertain but could be due to the environmental changes (e.g. change in hydrophobicity due to close proximity to the cell membrane) induced by protein-protein interactions, leading to a partial release of fluorophore-quencher pairs. In vivo imaging with Av-TM-Q7 and Traz-TM-Q7 in mice enabled the specific detection of lung metastasis with a high activation ratio and a low background signal [58]. Hama et al. used an antibody-based pre-targeting approach for the analysis of peritoneal metastasis. HER-1 positive A431 tumors were first pre-targeted with cetuximab, after 21 hrs, neutravidin-BODIPY-FL fluorescent conjugate was injected into the tumor and imaging was done 3 hrs after probe administration. The fluorescence efficiency of neutravidin-BODIPY-FL showed a 10-fold increase on binding to biotin. On-site activation of the probe lead to clear visualization of lesions of 0.8 mm or greater in size [55]. The efficacy of optical imaging in antigen targeted imaging of tumors was assessed in animal models bearing pulmonary metastasis induced by HER2 transfected NIH-3T3 cells. These cells produced fluorescent HER2 negative tumors due to the expression of RFP and non-fluorescent HER2 positive pulmonary metastases. Herceptin-RhodG complex non-specifically attached with less than 4% to HER2 negative tumors, while it showed a sensitivity of 100% by reacting with all the 3T3/HER2+ tumors [54]. Although, 100 μM lesions were detectable, but poor sensitivity of image acquisition methods limited the accuracy to clearly visualize tumor lesions of 0.8 mm or greater in size [55].

Infrared imaging is another promising development in the field of optical imaging due to its deep penetration ability and high sensitivity. Absorption coefficients of near infrared (NIR) wavelengths are low resulting in deep penetration up to centimeters under the skin. Further, low tissue autofluorescence in this range favors imaging. But the imaging efficiency of infrared imaging probes was limited due to their poor photostability, low quantum yield, high plasma protein binding rate, undesired aggregation and mild fluorescence in aqueous solution. Further, coupling with tumor targeting agents caused disturbance in the structure of NIR dyes or tumor-targeted ligands leading to loss of fluorescence. However, this limitation of NIR dyes indocyanine green (ICG) was harnessed by Ogawa et al. for on-site activation of fluorescence. Ogawa et al. conjugated the ICG to the antibodies daclizumab (Dac), trastuzumab (Tra), or panitumumab (Pan) directed against CD25, HER2 and EGFR-1, respectively [59]. Since the fluorescence intensity of ICG reduces drastically upon conjugation with protein fragments, ICG-antibody complexes were non-fluorescent until inside the target cell. Upon internalization, the complex dissociates resulting in bright fluorescence from released ICG. CD25-expressing tumors were specifically visualized with Dac-ICG, while tumors overexpressing HER1 and HER2 were successfully identified in vivo by using Pan-ICG and Tra-ICG, respectively. A high background signal was observed in the liver during first 24 hrs possibly due to the catabolism of loosely bound ICG in the liver which caused scattered background. However, the loosely bound ICG was cleared rapidly by liver and better tumor to background ratio was observed by day 3 that resulted in improved images.

The near-infrared cyanine (Cy) probes are good fluorescent agents for tumor imaging dyes due to their small size, good aqueous solubility, pH insensitivity (pH 3–10), and low non-specific binding [60]. Their long excitation wavelength (NIR, 650–900 nm) has made them suitable candidates for live animal imaging. In vivo NIR imaging of anti-EGFR antibody Erbitux in conjunction with Cy5.5 showed specific uptake in breast tumor during xenografts studies with MDA-MB-231 or MCF-7 tumors. Both in vitro and in vivo studies showed a specific uptake of conjugate in MDA-MB 231 cells [61]. Rosenthal et al. used an anti-EGFR mAb (Cetuximab) labeled to Cy5.5 fluorophore for in vivo detection of tumors in mice bearing head and neck squamous cell carcinoma engrafts. Image analysis showed that the probe positively accumulated in the tumor [62]. Similarly, anti-EGFR scFv labeled with near infrared dye BG-747 was used for imaging subcutaneous pancreatic carcinoma xenograft. This scFv showed better accumulation in the tumor and rapid blood clearance as compared to full-length cetuximab [63]. Montet et al. used dual target imaging with two different fluorescent probes, namely Cy5.5 labeled Herceptin antibody for HER2 receptor expression and cross-linked supermagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle (CLIO) for angiogenesis. This imaging system provided a three-dimensional resolution [64]. In an interesting study, to locate endothelial cells in tissues (to image angiogenesis), anti-CD31 antibody was conjugated with the NIR probe cy5.5. A strong signal was observed in mice bearing HUVEC-seeded Matrigel implants. Bright staining of vessel-lining cells in animals at 30 days after the implantation suggested the presence of intact and viable human endothelial cells. Non-specific signal observed in the spleen was attributed to labeled antibody aggregation with potential opsonization in plasma [65]. This conjugate of anti-CD31 antibody in conjunction with a NIR probe is a promising imaging agent for the detection of angiogenesis. Further, Zou et al. used Cy 7 which has increased penetration ability and low autofluorescence in comparison to Cy5.5 for imaging of colorectal cancer xenografts using both murine and humanized CC49 (anti-TAG-72 antibody) [66]. Although widely used cyanine dyes, are not approved by FDA for clinical studies and limited studies have been done to test their toxicities. Thus, these agents will have to undergo extensive toxicity testing before being used in clinical studies. Further, the major issue with their widespread use is the constant active state of NIR probes and non-specific signal in non-targeted tissues (lungs, spleen and liver).

To overcome the problem of fluorophore “always ON” and to determine its internalization in the targeted cell after binding to a particular receptor, Alford et al. used the idea of the fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLI). Fluorescence lifetime is the average amount of time a fluorophore spends in its excited state before returning to the ground state. For this, trastuzumab was conjugated to Alexa Fluor750 in ratios of either 1:8 (self-quenched conjugate) or 1:1 (unquenched conjugate). The quenched conjugate showed increased FLI in comparison to unquenched conjugate upon uptake into HER2 positive 3T3 cells. Although this is a good way to enhance the quality of imaging, the authors did not observe any significant difference in vivo using the two set of fluorophores. Further optimization of FLI is required to get a better imaging contrast [67].

Imaging efficiency of optical imaging probes has been cross-validated in many studies. Sampath et al. assessed the targeting capabilities of dual-labeled (111In-DTPA)n-trastuzumab-(IRDye800)m (labeled with 111In, a γ emitter, and a NIR fluorescent dye) with in vitro microscopy and with standard in vivo models of subcutaneous xenografts after intravenous administration. Superior specificity in binding to HER2-overexpressing SKBR3-luc xenografts was observed with dual-labeled agent. The (111In-DTPA)n-trastuzumab-(IRDye800)m conjugate showed the highest tumor to muscle ratio (2.25 ± 0.2) when compared with other conjugates [68]. Similarly, in SPECT analysis, a significant uptake of (111In-DTPA)n-trastuzumab-(IRDye800)m was observed in the tumor region compared with the muscle region. Both optical imaging using anti-P selctin scFv conjugated to NIR label Cy5 and radio-labeled 111In-DTPA showed significant tumor-specific binding to P-selectin in irradiated tumors compared to non-irradiated tumors in athymic nude mice bearing a lung tumor. Both of the modalities complemented each other’s results. Even though NIR imaging probes are gaining popularity in recent years, there are many challenges which need to be overcome before their successful use in the clinic. These include synthesis of novel probes with high quantum yield, deep tissue penetration and better conjugation chemistries. In case of flouresence and luminisence based imaging probes, although the use of charge coupled device (CCD) cameras along with the mathematical modeling systems for detecting and analyzing signal have enhanced their utility, but limited senstivity has restricted their use to xenograft models. Further, the intrinsic fluorescence of biomolecules poses a problem when fluorophores that absorb visible light (350–700 nm) are used. Apart from infrared imaging modalities, considerable interest is being generated for the use of labeled quantum dots in the field of optical imaging.

3.1.1 Quantum Dots (QD)

Quantum dots (QD) or semiconductor nanocrystals are light-emitting colloidal nanocrystals. QD have a broad excitation spectrum but a narrow range of emission wavelengths controllable by size and composition of the core. QD are generally made from hundreds to thousands of atoms of group II and VI elements or group III and V elements of the periodic table. The advantages of quantum dots include: i) size tunable photoluminescence spectra, ii) high threshold photobleaching resulting in long-term monitoring, iii) flexible surface characteristic for conjugation to a variety of labels, and iv) broad absorption spectra. The best available QD fluorophore for biological applications are made of cadmium selenide cores coated with a layer of ZnS due to its refined chemistry. QDs exhibit strong light absorbance, bright fluorescence, narrow symmetric emission bands, and high photo stability [69]. Conjugation of QD with biomolecules like DNA, antibodies and peptides results in hybrids that have properties of both materials, namely, spectroscopic characteristics of nanocrystals and biomolecular function of the surface attached entities. With these properties, quantum dots hold promise for non-invasive imaging. Yang et al. showed that quantum dots conjugated with anti-EGFR scFv specifically bind to EGFR expressing cells and undergo internalization [70]. Gao et al. designed a bioconjugated QD suitable for in vivo targeting. These nanoparticles contained an amphiphilic tri-block copolymer for in vivo protection, an antibody recognizing the PSMA and multiple PEG molecules for improved biocompatibility and circulation. Due to antibody targeting, QD accumulated in the tumor and enabled spectral imaging of tumor xenografts [71]. This study also demonstrated that tumor antigen specific antibody mediated active targeting of QD was superior to passive targeting using PEG conjugated QD.

Gonda et al. employed targeted QDs to study alterations in the membrane fluidity of human breast cancer cells during various stages of metastasis in vivo using a mouse xenograft model. QDs were conjugated with an antibody targeting Protease Activated Receptor 1 (PAR1)-a cell surface G-protein coupled receptor that is critical for cell migration and invasion to study PAR1 protein dynamics (expressed as diffusion constant) as a measure of membrane fluidity. Following the administration of QDs intravenously, membrane dynamics were imaged in the tumor with a spatial precision of 7–9 nm under a confocal microscope using a custom designed stage. Tumor cells representing four stages of metastasis- cells far from blood vessels in tumor, near the vessel, in the bloodstream, and adherent to the inner vascular surface-were imaged to determine the dynamics of the PAR1 protein. Dramatic changes in the membrane fluidity were observed in the cancer cells at various stages of the metastatic process. While the tumor cells far from blood vessels exhibited least membrane fluidity, a remarkable increase in membrane fluidity was observed at locally formed pseudopodia. The membrane fluidity further increased during intravasation, reached its peak inside the blood vessel and decreased during extravasation. The approach holds immense potential to visualize morphological (and possibly molecular) alterations in tumor cells in various microenvironments (primary tumor, blood vessel, stroma) with a high spatial resolution in real time, and hence, can contribute to a greater understanding of cancer metastasis at the nonometer-scale [72].

Apart from intact antibodies, antibody fragments have been conjugated with QDs. Recently, Barat et al. conjugated anti-HER2 cys-diabodies with CdSe/ZnS QD which showed spectral properties similar to unconjugated QD and specific reactivity with HER2 in immunofluorescence and flow cytometric studies [73]. QD-AFP-ab [CdSe/ZnS QDs with maximum emission wavelength of 590 nm (QD590) linked to alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)] antibody probe complexes were used to image tumors and metastasis in nude mice bearing xenografts of the human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell line HCCLM6. The probes exhibited specific targeting to the tumor and its metastases without any significant acute toxicity [74]. Imaging efficacy of QDs has been compared with small molecule fluorophore Alexa 680 conjugated to a humanized anti-IGF1R mAb AVE-1642 in a breast cancer xenograft model. In comparison to Alexa 680, which is specifically localized in tumor xenografts, it was found that QDs fluorescence was observed mainly in reticuloendothelial systems. The main cause for this localization was speculated to be the ingestion of nano-sized particles by macrophages. In earlier studies, it was observed that smaller QDs (with a size less than 5.5 nm), but not large QDs, could be cleared through renal excretion [75]. Although quantum dots are a promising multiplex imaging modality and show promising results in conjugation with targeting agents, there are some inherent limitations to their use. These limitations include a varied degree of cytotoxicity (nephrotoxicity of cadmium in its ionic form), limited toxicological studies, autofluorescence, scarcity of quantum dot probes in the NIR range where autofluorescence is less, limited penetration to deeper tissues for in vivo imaging, and limited availability of imaging instruments for humans. Further, QDs with longer emission wavelengths have been observed in the body upto two years after imaging [76]. This nonspecific uptake may potentially hinder the application of QDs in clinical settings. However, due to their unique spectral qualities, enhanced stability, ability to be tagged and conjugated with various probes in combination with antibodies, QDs can become powerful bioimaging agents in the future.

3.2 Ultrasound

Ultrasound (US) is a cross-sectional imaging modality and refers to sound at a frequency higher than 20 kHz. Clinical diagnostic ultrasound scanners use frequencies in the range of 1MHz to 20MHz. The principle of US is that pulses of ultrasound are sent out through arrays of transducers (probes), the returning echoes are captured and analyzed to build a two-dimensional image of the plane being scanned and displayed using a grey-scale display to code the intensity of the returning echoes, thus producing an image. Ultrasound contrast agents are designed to alter the absorption, reflection or refraction of sound to enhance differentiation of the signal from that of the surrounding sample. Targeted ultrasound contrast agents are site-directed contrast agents specifically enhancing the signal from pathologic tissue that would otherwise be difficult to distinguish from surrounding normal tissue. Microbubbles (MBs), the US contrast agents and are gas filled structures encapsulated by a lipid shell, polymer or proteins and when injected into the blood stream enhance signals from the target tissues [77, 78]. Along with their low cost and easy transport, their ability to be discriminated from background with high sensitivity make them a modality of choice for imaging. Specific ligands and antibodies have been attached to the MBs surface, leading to the accumulation of these agents in the target sites. Also, due to their large size, MBs rarely extravasate from vascular tissue [79]. Considering these properties of MBs, mAbs directed against endothelial cell adhesion molecules, such as P-selectin, mucosal addressin, cell adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1, have been conjugated to the surface MBs for targeted imaging of inflammation [80–82]. Further, MBs targeted to the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa integrin [83] and to fibrin [84] have been used for thrombus imaging. Targeted MBs based contrast imaging has helped in the functional characterization of tumor vasculature. Similarly, various angiogenic markers [vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGF-R), αvβ3 and endoglian] have been targeted using labeled MBs. VEGF-R was visualized using targeted contrast-enhanced US in rat glioblastoma and mouse angiosarcoma tumor models by using anti-VEGFR2 mAb coupled MBs (MBv) [85]. These MBv preferentially attached to murine angiosarcoma (SVR) cells expressing VEGFR under in vitro conditions. The antibody labeled MBv did show non-specific affinity with negative control murine myoblast cells. Signal enhancement with MBv was observed specifically in tumor vessel endothelial cells, while no signal was observed by direct attachment to the tumor under in vivo conditions, emphasizing that MBs do not leak from tumor vessels. Although specific targeting of MBs was observed, the study did not address sensitivity or specificity in comparison to other imaging modalities, and toxicities to the liver and kidney.

Efficacy of multi-targeted MBs (targeted to both intracellular adhesion molecule-1(ICAM-1) and P-selectins) were assessed in vitro, for detecting inflammation and early non-invasive assessment of vascular disease. MBs were directly conjugated to two antibodies, anti-VCAM-1 mAb and anti-sialyl Lewis x antigen, for binding to selectins using polyethylene glycol-biotin-streptavidin bridge. These dual-targeted MBs exhibited improved adhesion characteristics to endothelial cells in fluid shear environments compared to either of the single-targeted MBs [86]. This study conclusively showed that multi-targeting of contrast MBs for US imaging could differentiate among various degrees of endothelial dysfunctions. Further, dual targeted MBs directed against two markers of tumor angiogenesis, VEGFR2 and αvβ3, showed an enhanced signal in comparison to single labeled agents in the mouse bearing human ovarian tumor (SKOV3). To analyze the expression and molecular imaging of alpha v beta-3 (αvβ3), MBs were conjugated to peptides and antibodies specific for αvβ3 and incubated with endothelial cells in an in vitro system. These contrast agents showed higher sensitivity in binding to cell monolayers of HUVEC cells expressing αvβ3 [87]. In addition, MBs conjugated to biotinylated anti-αv-integrin Ab was used for noninvasive assessment of angiogenesis in a matrigel model of angiogenesis. This study showed that contrast enhanced ultrasound with MBs targeted to αv-integrin provides a noninvasive method for assessing therapeutic angiogenesis [88]. Yang et al. synthesized albumin MBs which could be easily modified with biotin. Biotinylated albumin MBs were further labeled with avidin. Specific binding of biotinylated anti-CD147 antibody was observed with these MBs. Under in vitro conditions, rosette formation was observed in hepatocellular carcinoma cells expressing CD147 and not with normal hepatocytes using these MBs. However, the utility of these MBs under in vivo conditions and their behavior as contrast agents following cellular internalization remains to be explored [89]. Although there are reports stating that only a small number of MBs are required to get appropriate contrast for imaging, further studies are needed to assess the overall sensitivity of targeted MBs, to determine the amount of antibody sufficient to target MBs to the desired site, and to determine the comparative efficacy of MBs in comparison to nuclear and other optical imaging modalities.

3.3 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI primarily uses the magnetic resonance signal produced from the hydrogen atoms of objects under the influence of a strong magnetic field for constructing three dimensional maps. Positive and negative contrast agents containing a metal ion are used to enhance MRI sensitivity. Positive contrast agents (appearing bright on MRI) are small molecular weight compounds containing gadolinium (Gd), manganese or iron as their active element. While the negative contrast agents (appearing predominantly dark on MRI) are small particulate aggregates often termed super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) or ultra-small super paramagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) particles having an iron oxide core containing iron atoms and covered by a polymer shell usually made of dextran or polyethylene glycol. Although it is a powerful imaging modality with a resolution capacity of 10–100 μm and exquisite soft tissue contrast (Fig. 3), its major drawbacks are low sensitivity, low retention time of positive contrast agent, relatively long imaging times, and large amounts of contrast agents to be injected.

Since conventional contrast agents like Gd, lack specificity, targeted contrast agents are being developed by conjugating paramagnetic compounds to various peptides, ligands, antibodies and antibody fragments that target specific tumor cell surface antigens. Due to their specific targeting, antibody fragments and antibodies have been used with both positive and negative contrast agents. In one of the earliest studies, Gd ions were conjugated to anti-CEA F(ab)2 using poly-lysine diethylenetriaminepentaacetate (DTPA). These were evaluated in LS174T tumor xenografts using a paramagnetic load of 24–28 metal ions (Gd) per Fab molecule. The MR imaging of the colon carcinoma xenografts using this Fab construct showed high signal intensity [90]. Gd was conjugated to melanoma specific antibody (9.2.27) using DTPA to image melanoma tumors. Gd-DTPA-9.2.27 conjugate was compared for its efficacy with Gd-hematoporphyrins. MRI using Gd-DTPA-9.2.27 exhibited improved contrast and precise anatomic localization of the mouse melanoma xenografts as compared to Gd-hematoporphyrins. Biodistribution studies showed an uptake of 35% of Gd-DTPA-9.2.27 conjugate in the tumor at 24 hrs, whereas the uptake for a non-specific control Ab was only 3%. The uptake of Gd-DTPA-9.2.27 was found to be better than Gd conjugated to porphyrins, which had an uptake of 28% [91]. Gadolinium conjugated mAb A7 (recognizing 42 kDa surface protein on colon carcinoma cells) showed better accumulation in tumors and had a good contrast at the 48 hrs time point as compared to Gd conjugated normal IgG in mice studies [92]. An interesting approach using a two-component Gd based MR contrast agent to image HER2 expressing tumors was designed by Artemov et al.[93]. Biotinylated anti-HER2 mAb, which binds to the extracellular domain of HER2, was first injected, and then the antigen-antibody complex was imaged using avidin conjugated Gd [93]. This two-step strategy was evaluated in an experimental mouse model of breast carcinoma derived from HER2/neu transgenic mice which effectively delivered the contrast agents in the tumor interstitium with a significant signal intensity enhancement in HER2 expressing tumors at the end of 8 and 24 hrs. This strategy was advantageous over a single large molecular size contrast agent due to the difference in the molecular size of the mAb (150 KDa) and avidin-Gd conjugate (70 KDa). Zhu et al used a three-step pre-targeting approach for MR imaging of athymic mice bearing HER-2/neu overexpressing BT-474 human breast tumor xenografts. Gadolinium was conjugated to generation 4 PAMAM dendrimer (bG4D-Gd) having 64 easily modifiable amine groups with moderate blood circulation time. The animals were first injected with biotinylated trastuzumab, and 48 hrs after trastuzumab injection animals were treated with avidin which was followed by biotinylated gadolinium conjugated dendrimer (BG4D-Gd). No significant differences were observed due to pre-targeting using the biotin-avidin/streptavidin recognition system, possibly due to the saturation of the avidin/streptavidin binding sites by biotinylated trastuzumab. Therefore, subsequent binding of bG4-Gd was blocked [94]. In imaging angiogenesis, liposomes entrapping GD-DTPA in conjunction with anti-CD105 antibody showed specific enhancement at new microvessels in glioma bearing rats in comparison to GD-DTPA entrapped liposomes or IgG labeled liposomes. These liposomes showed early contrast enhancement with the signal increasing up to 120 minutes. The study uniquely described the ability of antibody-coated liposomes for MR imaging of early angiogenesis [95]. While direct conjugation strategies using Gd based contrast agents appear promising, it requires higher concentrations of Gd to be accumulated in the target tissue in the range of 10−4 mol/L, when compared to radionuclide imaging, which needs only about 10−11 mol/L [96]. This higher level of accumulation of Gd ions could lead to cytotoxicity. For this reason, the possibility of utilizing smaller magnetic nanoparticles was evaluated as a contrast agent for MR imaging.

Another alternative approach for the development of improved immunocontrast agents for MRI involves the conjugation of iron oxide nanoparticles to carcinoma specific antibodies. In one of the earliest studies, monocrystalline iron oxide nanoparticles (MION) were conjugated to L6, a murine antibody recognizing a propressophysin-like protein abundantly expressed on the cell surface of human small-cell lung carcinoma, breast carcinoma and colon carcinoma [97]. The mAb-conjugated MION were evaluated in nude rats with intracranial lung carcinomas and were compared with MION alone and MION conjugated to P1.17, a non-specific mAb recognizing the mouse myeloma protein. MR imaging after direct intra-venous (i.v.) administration of the MION-L6 showed an enhanced contrast at tumors with a high concentration of Ab accumulating in the area of dense tumor cells when compared to surrounding necrotic areas. On the other hand, MION-P1.17, the control Ab conjugate, showed non-specific changes. Further, anti-EGFR mAb labeled poly (lactic acid-co-l-lysine) nanoparticles showed binding to hepatocellular carcinoma cells by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy under in vitro conditions and better targeting to SMMC-7721 xenografts under in vivo conditions in comparison to the control nanoparticle. [98].

Superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) is another class of negative contrast agents used in MR imaging. Toma et al. developed a SPIO colloid based immunocontrast agent that would selectively accumulate in rectal carcinomas for the diagnosis of local recurrence [99]. Biodistribution studies showed preferential accumulation of anti-colorectal carcinoma glycoprotein mAb A7 conjugated to SPIO in the tumors. MRI of tumor xenografts using this agent showed that the signal intensity was reduced at the margin of the tumor and the heterogeneity in contrast agent accumulation in tumor was attributed to tumor blood supply. The study showed that A7-SPIO is a potentially useful MR contrast agent to diagnose recurrent rectal carcinomas. Further, biodistribution studies of 125I labeled mAbA7-FML (ferromagnetic ligosite particles with cumulative magnetic moment approximately ten times higher than other paramagnetic conjugates) showed 9.8 times higher accumulation of radioactivity in the colon tumor when compared to the normal colon. The MR imaging of the tumor xenografts showed that signal intensity was reduced in the tumor by the administration of excess A7-FML, whereas, the animals injected with normal mouse IgG-FML did not show any change in signal intensity of the tumors. Biotinylated anti-CD70 antibody labeled ultra-small super paramagnetic iron oxide (USPIO)-nanoparticles showed improved MRI contrast in detecting pseudometastasis generated by D430B human lymphoma in a two-step targeting approach [100]. Similarly, herceptin-coated USPIO nanoparticles specifically accumulated to sites in mice having breast tumor allografts and showed T 2-weighted magnetic resonance images of high contrast. Importantly, these particles were able to detect tumors derived from cell lines expressing lower levels of HER2 [101]. A list of MRI contrast agents used in conjunction with antibodies and antibody fragments is summarized in Table III. All of these observations demonstrate the feasibility of using a targeted MRI agent for improved imaging. Although the sensitivity and specificity of MRI is being enhanced using relaxivity contrast agents having multiple paramagnetic centers and antibodies for specific targeting, various issues still need to be resolved for successful use in the clinic. The large molecular size of antibodies in combination with the large size particles limit the ability of MRI particles to permeate deep into tumor tissues; moreover, the interaction of the Fc receptor with macrophages leads to their accumulation at non-specific sites. Strategies to overcome these impediments would help in the successful use of targeted MRI for improved imaging.

Table III.

MRI agents under development for imaging tumors.

| MRI agent | Targeting antibody | Target | Tumor | Experimental Condition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gd ions | Anti-human melanoma cell line antibody 9.2.27 | Melanoma cell line | Human melanoma xenografts | In vivo | [91] |

| Gd conjugate | mAb A7 | 42 kDa surface protein on colon/ rectal carcinoma cells | Colorectal carcinoma | In vivo | [92] |

| GD-DTPA | Anti-VEGFR2 Ab | VEGFR2 | CT-26 adenocarcinoma tumor model | In vivo | [118] |

| Biotinylated Gadolinium PAMAM 4 dendrimer | Biotinylated trastuzumab | HER-2/Neu receptors | Breast tumor | In vivo | [94] |

| SPIO | Anti-CEA Ab | CEA | Colon tumor | In vivo | [119] |

| Streptavidin- conjugated SPIO | Anti-HER2/Neu mAb | HER-2/Neu receptors | Breast cancer | In vitro | [120] |

| Ferumoxides (SPIO) | mAb A7 | Colorectal tumor antigen | Colorectal carcinoma | In vivo | [99] |

| Iron oxide nanocrystals (Fe3O4) | Herceptin | HER-2/Neu receptors | NIH3T6.7 | In vivo | [121] |

| SPIO | mAb A7 | Colorectal carcinomas glycoprotein | Rectal carcinomas | In vivo | [99] |

| Streptavidin-SPIO | Anti-PSMA antibody | PSMA | Human prostate cancer cells | In vitro | [122] |

| Anti-Biotin labeled USPIO | Biotinylated Anti-CD70 antibody | CD70 | D430B human lymphoma | In vivo | [100] |

| MION | mAb L6 | Surface antigen | Intracranial tumor LX-1 | In vivo | [97] |

| MION | Anti-HER2 Anti-9.2.2.27 antibody | HER2, Proteoglycan sulfate | Melanoma and mammary cell lines | In vitro | [123] |

| Poly(lactic acid-co-l-lysine) nanoparticles | Anti-EGFER mAb | EGFR | Hepatocelluar carcinoma cells | In vitro | [98] |

SPIO (super paramagnetic iron oxide); USPIO (ultra-small super paramagnetic iron oxide); DTPA (Diethylenetriamine pentaacetate); MION (monocrystalline iron oxide nanoparticles).

4. Emerging Imaging Modalities

This review on antibody-based imaging agents would be incomplete without a brief discussion on antibody-targeted nanoparticles. Nanoparticles are nanosized carriers used for the delivery of drugs. Recently, there have been intense efforts to develop multifunctional nanocarriers for targeted delivery of drugs. These multifunctional nanocarriers also incorporate antibodies for specific and effective tumor targeting and delivery of therapeutic and diagnostic payloads. Nanoshells are optically tunable nanoparticles that contain a dielectric core surrounded by a thin gold shell. These nanoshells may be designed to scatter and/or absorb light over a broad spectral range. Thus, depending on the wavelength of light chosen, these nanoparticles can be utilized for imaging and for photothermal therapy. Loo et al. engineered anti-HER2 Ab targeted nanoshells for optical imaging and photothermal therapy of HER2-expressing tumor cells [102]. However, this report only showed the in vitro analysis of the efficacy of these particles and the in vivo applicability of this approach remains to be demonstrated. Utilizing liposomes coated with a cancer cell specific anti-nucleosome antibody and labeled with [111]In, Elbayoumi et al. showed enhanced tumor visualization by gamma camera imaging [103]. These antibody targeted liposomes accumulated in tumor 3–5 times more when compared to normal tissues. Erdogan et al. developed liposomes loaded with Gd, the MRI contrast agent, and modified these with cancer cell specific anti-nucleosome antibody and evaluated the in vitro efficacy and proposed its use as a promising imaging agent [104]. Similar to this, optical coherence tomography (OCT), which detects a reflected light source from the sample using refractive index mismatching, is used in combination with antibodies for early detection of neoplasias. Resolution efficiency of OCT is better than MRI, CT and ultrasound. Lu et al. observed that anti-HER2 and anti-S6 aptamer conjugated multifunctional nanogold can detect HER2 positive SKBR-3 cells with very high sensitivity by simple colorimetric assay. Clear colorimetric changes were observed in nanoparticles on the addition of the cancer cell, which was quite specific to HER2 positive cells [105]. PEGylated Au nanoparticles with anti-EGFR antibody coating were prepared to prevent agglomeration of nanoparticles as well as to assess specific uptake of these conjugates by EGFR-expressing cells in oral cancer in a hamster cheek pouch model. Although Au nanoparticle agglomeration in vivo was effectively diminished, no selective antibody-mediated binding of the Au nanoparticles was observed in this study [106]. The biological samples usually scatter weak light; however, the intensity of scattered light increases dramatically in the vicinity of metallic nanoparticles. The metallic nanoparticles on excitation, at a particular wavelength exhibit surface plasmon resonance and start resonating light. Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS), a Raman Spectroscopic (inelastic scattering of light on its interaction with material) technique, provides a greatly enhanced Raman signal from Raman-active analyte molecules (metallic particles), causing a better contrast of surrounding molecules. Due to its ability to detect picomolar amounts of targeted molecules, SERS is becoming a predominant imaging modality. SERS provide multiple advantages over existing imaging modalities including: i) unique spectral properties of SERS nanoparticles with easily resolved narrow peaks makes multiplex imaging a possible venue, ii) possibly less toxicity due to the inert nature of SERS nanoparicles (Gold, silica), moreover colloidal gold particles coated with a protective layer of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-exhibit excellent in vivo biodistribution and pharmacokinetic properties upon systemic injection, iii) SERS probes enhance the Raman scattering of adjoining molecules by as high as 1014–1015 fold, leading to the detection of a single molecule [107, 108]. SERS is gaining applicability in localized and surface tumors, however, its uses are limited in imaging of deep tumors due to the limited depth of penetration associated with the Raman microscope (5 mm) and the non-specific uptake of these particles (120 nm) by the reticuloendothelial system [109]. Antibodies have not been used with SERS probes to date. However, looking at multiplexing of SERS probes and the high specificity of antibodies for their targeted epitopes, the combination of SERS with antibodies offers promising prospects.

5. Conclusion and Perspectives