Non-technical summary

Cyclic AMP-mediated signalling plays an important role in the development and plasticity of synaptic circuits, and adenylate cyclase 1 is a major enzyme for cyclic AMP production in the brain of newborns. We show that in mice deficient in adenylate cyclase 1, developmental strengthening and experience-dependent plasticity of excitatory synapses are impaired, but developmental pruning of the synapses is not affected. These results increase our understanding of the processes by which neuronal circuits are formed and modified during development.

Abstract

Abstract

Synaptic refinement, a process that involves elimination and strengthening of immature synapses, is critical for the development of neural circuits and behaviour. The present study investigates the role of adenylate cyclase 1 (AC1) in developmental refinement of excitatory synapses in the thalamus at the single-cell level. In the mouse, thalamic relay synapses of the lemniscal pathway undergo extensive remodelling during the second week after birth, and AC1 is highly expressed in both pre- and postsynaptic neurons during this period. Synaptic connectivity was analysed by patch-clamp recording in acute slices obtained from mice carrying a targeted null mutation of the adenylate cyclase 1 gene (AC1-KO) and wild-type littermates. We found that deletion of AC1 had no effect on the number of relay inputs received by thalamic neurons during development. In contrast, there was a selective reduction of AMPA-receptor-mediated synaptic responses in mutant thalamic neurons, and the effect increased with age. Furthermore, experience-dependent plasticity was impaired in thalamic neurons of AC1-KO mice. Whisker deprivation during early life altered the number and properties of relay inputs received by thalamic neurons in wild-type mice, but had no effects in AC1-KO mice. Our findings underline a role for AC1 in experience-dependent plasticity of excitatory synapses.

Introduction

Selective elimination and strengthening of immature synapses is a common feature of neural development in vertebrates (Lichtman & Colman, 2000; Luo & O'Leary, 2005; Kano & Hashimoto, 2009). During early phases of neural development, each neuron makes weak synaptic connections with a large number of cells. Many of these early connections are later eliminated, while the remaining ones are strengthened. This refinement of synapses is essential for the formation of neural circuits and the development of behaviour. Although neuronal activities play a central role in synaptic refinement, little is known about the molecular mechanisms involved.

Cyclic AMP is an essential second messenger that plays key roles in many aspects of neural development (Wang & Storm, 2003; Ferguson & Storm, 2004). Cyclic AMP is produced from ATP through catalytic enzymes called adenylate cyclases (ACs). Of the 10 mammalian ACs identified so far, AC1 and AC8 are the only two that can be directly activated by Ca2+–calmodulin. Adenylate cyclase 1 is of particular interest because it is highly expressed in the brain during early life, while AC8 is broadly expressed in adults (Nicol et al. 2005; Allen Brain Atlas: http://developingmouse.brain-map.org/). The early presence and calcium sensitivity of AC1 make it an interesting candidate for activity-dependent mechanisms. Adenylate cyclase 1-mediated signalling may be particularly important for synaptic plasticity in newborns. It has been shown that long-term potentiation in the hippocampus of newborn rodents requires cAMP-dependent protein kinase A but not Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (Yasuda et al. 2003).

Recent studies have demonstrated a role for AC1 in the development of neuronal connections in the brain. In AC1 mutant mice, the whisker-specific map was absent in the somatosensory cortex (Welker et al. 1996; Abdel-Majid et al. 1998), and axons of retinal ganglion neurons failed to segregate properly in the lateral geniculate nucleus and the superior colliculus (Ravary et al. 2003). Studies using co-culture of the retina and the tectum have demonstrated that AC1 is required for ephrin-mediated retraction of retinal ganglion axons (Nicol et al. 2006). Although such findings strongly support a role of AC1 in the elimination of redundant synapses during early life, direct evidence at the single-cell level is still missing. In contrast, recent studies have demonstrated a role for AC1 in synaptic strengthening. Patch-clamp studies in acute brain slices have shown that thalamocortical synapses in AC1 mutant mice contain fewer AMPA receptors (AMPARs), suggesting a role of AC1 in AMPAR trafficking in immature neurons (Lu et al. 2003). However, it is unknown whether AC1 is implicated in sensory-experience-dependent strengthening of excitatory synapses during early life.

To address these questions, we have analysed developmental refinement of whisker relay synapses in the thalamus of mice carrying a null mutation of AC1. Tactile information from large whiskers is relayed from the principal sensory trigeminal nucleus (PrV) to the ventral posteromedial nucleus (VPm) of the thalamus through the lemniscal pathway. Previous studies have shown that the PrV-to-VPm projection undergoes extensive refinement during the second week after birth (Arsenault & Zhang, 2006; Wang & Zhang, 2008) and that AC1 is highly expressed in both pre- and postsynaptic neurons of this connection (Nicol et al. 2005). Using patch-clamp recordings in acute brain slices, we show that AC1 is not required for the elimination of redundant inputs, but is important for experience-dependent strengthening of synapses.

Methods

Animals

Adenylate cyclase 1-knockout (AC1-KO) mice were generated as described previously (Wu et al. 1995). This strain has been backcrossed to C57BL/6J for 11 generations, and is maintained by heterozygous mating. Genotypes were determined by PCR using the following three primers: 5′-CTT-TTC-CTG-GCG-CTG-TTC-GTG-3′ (wild-type forward), 5′-CTG-TGA-CCA-GTA-AGT-GCG-AGG-3′ (wild-type reverse) and 5′-GAG-AAT-GTT-CCT-GGT-CCT-GTC-G-3′ (mutated forward), which respectively amplify 300 and 650 bp fragments from the wild-type (WT) and mutated alleles. A total of 60 mice were used in this study. Homozygous mice and wild-type littermates were used in most of the experiments, and heterozygous mice were used in some experiments. All procedures are in accordance with the NIHGuide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the principles of UK regulations as described by Drummond (2009), and have been approved by The Jackson Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee.

Whisker deprivation

Mice aged P13 (13 days postnatal with the day of birth as P0) were anaesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane (3% in oxygen). Large whiskers on the snout were pulled out gently with a pair of forceps. This method does not damage follicles. Mice were checked every other day until the day of recording, and whisker plucking was repeated when necessary.

Slice preparation

Mice were killed by decapitation. Sagittal sections of 300 μm thickness were prepared using methods described previously (Arsenault & Zhang, 2006). Slices were kept in artificial cerebral spinal fluid containing (mm): 124 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1.3 MgCl2, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3 and 20 glucose, saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at room temperature (21–23°C).

Patch-clamp recording

Recordings were made at 32–34°C. The pipette solution contained (mm): 110 caesium methylsulfate, 20 TEA-Cl, 15 CsCl, 4 ATP-Mg, 0.3 GTP, 0.5 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 4.0 QX-314 and 1.0 spermine (pH 7.2; adjustd to 270–280 mmol kg−1 with sucrose). Electrodes had resistances between 2 and 4 MΩ. For quantal event recording, pipettes were pulled from low-loss borosilicate capillaries (no. 0010; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA), and coated with Sylgard. Whole-cell recordings were made at the soma of VPm neurons with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The series resistance (Rs), usually between 7 and 14 MΩ, was not compensated. Data were discarded whenRs was >18 MΩ. A concentric bipolar electrode (FHC, Bowdoin, ME, USA) was placed in the medial lemniscus, and stimuli (60–150 μs, 10–900 μA, with the centre pole being negative) were applied at 0.1 Hz. GABAergic transmission was blocked by 100 μm picrotoxin in the bath. Experiments were conducted using AxoGraph X (AxoGraph Scientific, Sydney, Australia). Data were filtered at 4 kHz and digitized at 16 kHz.

Data analysis

All data were analysed blind using AxoGraph X and IgorPro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA). The number of inputs for each VPm neuron was estimated as we described previously (Arsenault & Zhang, 2006; Wang & Zhang, 2008). Briefly, EPSCs evoked from the same cell over a wide range of stimulus intensity were analysed to determine the number of increments in the evoked synaptic responses. At P16–17, the majority of neurons showed a single increment, with the rest of the neurons showing two or three increments. At P12–13, neurons showed one to four increments that could be easily identified and measured. At P7, however, VPm neurons showed a large number of small increments, which makes increment counting unreliable. This is particularly problematic for AMPAR EPSCs recorded at –70 mV because the amplitude of AMPAR EPSCs was small at P7. For P7 neurons, therefore, we estimated the input number from NMDA receptor (NMDAR) EPSCs recorded at +40 mV. We divided the amplitude of the third EPSC increment by three to provide an estimation of the average single-input response. We chose the third increment because it can be easily identified in all cells at P7, and our tests showed that it produces similar results as with the fifth increment (divided by five in this case). The maximal response of a cell was divided by the average single-input response to provide an estimation of the number of inputs for the cell.

For cells at P12–13, we quantified the disparity between individual inputs of multistep responses using the disparity ratio described previously (Hashimoto & Kano, 2003). The amplitudes of individual inputs of a given multi-innervated neuron were measured and numbered in the order of amplitude (A1, A2, …AN, withANbeing the largest). It follows that:

|

A disparity ratio of 1.0 indicates that all inputs in a given cell have the same amplitude.

For evoked quantal EPSCs recorded in Sr2+, data were filtered at 1 kHz, and events were detected using variable-amplitude template functions, with the rise time set at 1 ms and decay time set at 3 ms. For each neuron, 100–300 events were averaged to yield the mean quantal response.

Statistics were determined using IgorPro and InStat (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Throughout, means are given ±SEM. Means were compared using the Mann–WhitneyUtest. Distributions of cells with different numbers of inputs were compared using the χ2 test.

Results

Adenylate cyclase 1 is not required for elimination of redundant whisker relay synapses

The lemniscal pathway from the principal sensory trigeminal nucleus to the ventral posteromedial nucleus of the thalamus undergoes extensive remodelling during early life. In the mouse, each VPm neuron is connected with several PrV axons at 1 week of age; most of these early inputs are eliminated during the second week, so that by P16, the majority of VPm neurons are contacted by a single PrV axon (Arsenault & Zhang, 2006). The late phase of synaptic refinement (from P12 to P16) can be disrupted by sensory deprivation (Wang & Zhang, 2008). Adenylate cyclase 1 is highly expressed in both the VPm and PrV of the mouse from embryonic day 18 to P14 (Nicol et al. 2005; Allen Brain Atlas: http://developingmouse.brain-map.org/). To determine whether AC1 plays a role in synaptic remodelling, we examined the connectivity of the PrV-to-VPm pathway in mice carrying a null mutation of AC1 and wild-type littermates. Excitatory postsynaptic currents evoked in VPm neurons in acute brain slices by stimuli applied to the medial lemniscus. To examine synaptic responses mediated by AMPA and NMDA receptors selectively, EPSCs were recorded at –70 and +40 mV in the same cell.

At P16–17, the majority of VPm neurons from both WT and AC1-KO mice showed an all-or-none synaptic response (Fig. 1AandB), indicating that each of these neurons was innervated by a single PrV axon. A small number of VPm neurons of either genotype received two or three PrV inputs (Table 1). Collectively, the percentage of neurons receiving single or multiple inputs was not different between WT and AC1-KO mice at P16–17 (Fig. 1C;n = 23 cells from 4 WT mice, andn = 21 cells from 5 mutant mice;P> 0.9, χ2 test). In either case, about 80% of VPm neurons received a single PrV input. The mean number of inputs per cell was 1.19 ± 0.11 for WT and 1.20 ± 0.12 for AC1-KO mice (P> 0.9, Mann–WhitneyUtest). This finding indicates that deletion of AC1 has no effect on the number of PrV axons innervating each VPm neuron at P16–17.

Figure 1. Elimination of redundant whisker relay inputs proceeds normally in the ventral posteromedial nucleus of the thalamus (VPm) in the absence of adenylate cyclase 1 (AC1).

AandB, upper panels, excitatory synaptic currents recorded in a wild-type (WT;A) and a mutant VPm neuron (B) at P16 with stimulations applied to the medial lemniscus. For each neuron, EPSCs were recorded at both –70 and +40 mV with a range of stimulation intensities.AandB, lower panels show the plot of EPSC peak amplitudevs. stimulation intensity. Both neurons show all-or-none responses.C, distributions of VPm neurons receiving different numbers of relay inputs for mutant (open columns) and WT mice (grey columns) aged postnatal day (P)16–17. In both mutant and WT mice, about 80% of VPm neurons receive a single relay input.DandE, EPSCs (upper panels) and plots of EPSC amplitudevs. stimulation intensity (lower panels) from a WT (D) and a mutant VPm neuron (E) at P12.F, distribution of neurons receiving different numbers of relay inputs for mutant (open columns) and WT mice (grey columns) aged P12–13.G–Ishow the equivalent results obtained from WT and mutant VPm neurons at P7.

Table 1.

Percentage of wild-type and adenylate cyclase 1 knockout (AC1-KO) neurons receiving 1, 2, 3 and 4 or more inputs at postnatal day (P)7, P12–13 and P16–17

| Wild-type (%) | AC1-KO (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inputn | P7 n = 28 | P12–13 n = 23 | P16–17 n = 23 | P7 n = 30 | P12–13 n = 21 | P16–17 n = 21 |

| 1 | 3.6 | 65.2 | 87.0 | 3.3 | 61.9 | 85.7 |

| 2 | 10.7 | 26.1 | 8.7 | 10.0 | 28.5 | 9.5 |

| 3 | 14.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 20.0 | 9.5 | 4.8 |

| 4 or more | 71.4 | 4.3 | 0 | 66.7 | 0 | 0 |

Next we examined VPm relay synapses at P12–13, a period when the connectivity of this pathway is approaching the mature form (Arsenault & Zhang, 2006; Wang & Zhang, 2008). Data were collected from 21 cells from five mutant mice, and 23 cells from five WT littermates. Again, the pattern of innervation was not different between mutant and WT mice at this age (Fig. 1DandE; Table 1). As illustrated in Fig. 1F, about 35% of the VPm neurons from either mutant or WT mice received two to four relay inputs (P> 0.5, χ2 test). The mean number of inputs per neuron was 1.5 ± 0.1 for AC1-KO and 1.5 ± 0.2 for WT mice (P> 0.8). Previous studies in the cerebellum have shown that the differences in strength between multiple climbing fibres innervating the same Purkinje cell grow bigger prior to elimination of redundant inputs, and these changes can be quantified by estimating the disparity ratio in strength between individual inputs (Hashimoto & Kano, 2003). To determine whether AC1 deletion alters the disparity between individual steps of multifibre EPSCs, we calculated the disparity ratio in WT and mutant neurons that showed two or more steps at P12–13. There was no significant difference in the disparity ratio between WT and mutant neurons [0.66 ± 0.06 (n = 8) for AC1-KOvs.0.59 ± 0.09 (n = 8) for WT;P> 0.5].

To determine whether AC1 is involved in the early phase of synaptic development, we recorded from VPm neurons at P7. Data were collected from 28 neurons from five WT mice and 30 neurons from five mutant mice. Consistent with previous findings in B6 mice (Arsenault & Zhang, 2006), both AC1-KO and WT VPm neurons received multiple relay inputs at P7 (Fig. 1GandH; Table 1). The distribution of neurons receiving different input numbers was not significantly different between mutant and WT mice (Fig. 1I;P> 0.8, χ2 test). The average number of inputs for each VPm neuron was 5.0 ± 0.4 for mutant (n = 30) and 5.1 ± 0.5 for WT mice (n = 28;P> 0.5).

Together, these results demonstrate that pruning of redundant whisker relay inputs in the VPm does not require AC1 signalling.

Adenylate cyclase 1 promotes developmental strengthening of VPm relay synapses

In contrast to the lack of change in input number, we found significant reductions in synaptic strength of VPm relay synapses in AC1-KO mice. We analysed the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio, and the maximal EPSCs in AC1-KO and WT VPm neurons at P7, P12–13 and P16–17. The AMPAR/NMDAR ratio was calculated as the ratio of peak amplitudes at –70 and +40 mV in the same cell at the same stimulus intensity. The peak amplitude of EPSCs at –70 mV was entirely mediated by AMPA receptors, whereas that at +40 mV, due to the apparent lack of GluA2 subunit at the synapse, was almost entirely mediated by NMDA receptors (Wang & Zhang, 2008). In WT VPm neurons, the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio increased steadily between P7 and P17 (Fig. 2A, open circles). This developmental increase in AMPAR/NMDAR ratio was significantly disrupted in AC1-KO mice (Fig. 2A, grey squares). The ratio was not different at P7 between mutant and WT neurons (0.56 ± 0.05, n = 28 for WT; 0.52 ± 0.06, n = 30 for mutant;P> 0.3), but was significant smaller in mutants at P12–13 (1.54 ± 0.10, n = 23 for WT; 1.13 ± 0.08, n = 21 for AC1-KO;P< 0.005), and the difference became larger at P16–17 (2.10 ± 0.15, n = 16 for WT; 1.16 ± 0.10, n = 18 for AC1-KO;P< 0.001). These results indicate that AC1 is important for the development of VPm relay synapses between P7 and P17.

Figure 2. Developmental strengthening of relay synapses in the VPm was disrupted in adenylate cyclase 1 knockout (AC1-KO) mice.

A–C, left panels are scatter plots of data obtained from WT (open circles) and AC1-KO neurons (grey circles) at P7, P12–13 and P16–17; the right panels show the mean values.A, developmental changes in AMPA receptor (AMPAR)/NMDA receptor (NMDAR) ratio.BandC, developmental changes in the peak amplitude of the maximal EPSCs mediated by AMPA (B; measured at –70 mV) and NMDA (C; measured at +40 mV) receptors. *P< 0.01, **P< 0.005, Mann–WhitneyUtest.

To quantify the function of AMPA and NMDA receptors at the synapse, we measured AMPAR and NMDAR EPSCs at stimulus intensities that produce the maximal response at P7, P12–13 and P16–17. As illustrated in Fig. 2B, the amplitude of AMPAR EPSCs in WT neurons (open circles) increased by 87% between P7 and P12–13 and by 114% between P7 and P16–17 (852 ± 110 pA, n = 28 for P7; 1598 ± 135 pA, n = 23 for P12–13; 1824 ± 124 pA, n = 23 for P16–17;P< 0.0001, ANOVA;P< 0.01, P7vs.P12–13;P< 0.001, P7vs.P16–17, Dunn's multiple comparisons test). In comparison, the amplitude of AMPAR EPSCs in AC1-KO neurons increased by 40% between P7 and P12–13 and was steady between P13 and P17 (808 ± 131 pA, n = 30 for P7; 1129 ± 95 pA, n = 21 for P12–13; 1089 ± 79 pA, n = 18 for P16–17;P< 0.015, ANOVA;P< 0.05, P7vs.P12–13). The amplitude of AMPAR EPSCs was significantly smaller in mutant than WT neurons at P12–13 (P< 0.01) and P16–17 (P< 0.001), but no difference was found at P7 (P> 0.4). In contrast, the amplitude of NMDAR EPSCs was not different between WT and mutant neurons at all three ages (Fig. 2C; P7, 1430 ± 116 pA, n = 28 for WTvs.1354 ± 118 pA, n = 30 for mutant, P> 0.4; P12–13, 1059 ± 81 pA, n = 23 for WTvs.1054 ± 79 pA, n = 21 for mutant, P> 0.7; P16–17, 1061 ± 71 pA, n = 23 for WTvs.1021 ± 90 pA, n = 18 for mutant, P> 0.7). Together these results indicate that AC1 plays an important role in the upregulation of AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic responses in the thalamus during early life.

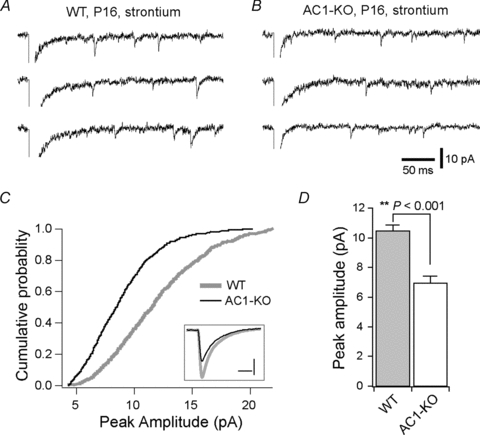

Each PrV axon makes a large number of synapses with a single VPm neuron (Peschanski et al. 1985; Williams et al. 1994). To determine changes at the single-synapse level, we recorded evoked quantal EPSCs at –70 mV in WT and AC1-KO neurons at P16–17. Replacing Ca2+ with 3 mm Sr2+ in the artificial cerebral spinal fluid reduced the initial synchronous response of EPSCs at –70 mV and caused a large number of asynchronous quantal EPSCs (Sr-EPSCs; Fig. 3AandB). The Sr-EPSCs in VPm neurons of AC1-KO mice were smaller than those in WT neurons (Fig. 3C). The mean peak amplitude was 6.9 ± 0.5 pA (n = 9) for AC1-KO and 10.5 ± 0.4 pA (n = 8) for WT (P< 0.001). In contrast, there was no difference between the two groups in the decay time constant of Sr-EPSCs (3.1 ± 0.1 ms for mutantvs.3.0 ± 0.2 ms for WT;P> 0.8). These results suggest that fewer functional AMPA receptors are present at individual VPm relay synapses in AC1-KO mice.

Figure 3. Reduction of quantal EPSC amplitude in AC1-KO neurons.

AandB, evoked quantal EPSCs recorded in the presence of 3 mm Sr2+ from a WT (A) and mutant VPm neuron (B) aged P16. The scale bars apply to bothAandB.C, distributions of Sr2+-evoked EPSC amplitude for WT (thick grey line) and mutant neurons (thin black line). The distributions were established by pooling 100 consecutive events from each of the recorded neurons (n = 8 from 3 WT mice;n = 9 from 3 mutant mice). The inset shows the averaged Sr-EPSCs from WT (grey) and mutant neurons (black); scale bars in inset represent 4 pA and 4 ms.D, the mean peak amplitude for WT (grey column) and AC1-KO neurons (open column).P< 0.001, Mann–WhitneyUtest.

Previous studies have shown that AC1 deficiency leads to a reduction of synaptic release probability in the neocortex (Lu et al. 2006). To test this possibility, we examined release probability at the VPm relay synapse in AC1-KO, wild-type and heterozygous littermates at P14–16. At these ages, heterozygous neurons were indistinguishable from wild-type ones in AMPAR/NMDAR ratio (1.76 ± 0.10, n = 11 for heterozygousvs.1.81 ± 0.12, n = 15 for WT;P> 0.7), amplitudes of AMPAR EPSCs (1867 ± 234 pA for heterozygousvs.1781 ± 272 pA for WT;P> 0.8) and amplitudes of NMDAR EPSCs (1048 ± 101 pA for heterozygousvs.972 ± 83 pA for WT;P> 0.5). Data from heterozygous and wild-type neurons were pooled as the control group. First we analysed paired-pulse responses at the VPm relay synapse. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, both mutant and control cells showed paired-pulse depression at –70 mV or +40 mV. With a 50 ms interpulse interval, paired-pulse ratios (PPRs) at –70 mV were 0.73 ± 0.02 for mutant (n = 13) and 0.72 ± 0.03 (n = 12) for control cells (P> 0.5); PPRs at +40 mV were 0.75 ± 0.02 for mutant (n = 13) and 0.76 ± 0.02 for control cells (n = 15;P> 0.5). The PPRs measured with a 100 ms interpulse interval were also not different between mutant and control cells at –70 or +40 mV (Fig. 4B;P> 0.5). There was no difference between heterozygous and wild-type neurons in PPRs at –70 mV (0.73 ± 0.03vs.0.71 ± 0.04 at 50 ms, P> 0.5; 0.76 ± 0.02vs.0.74 ± 0.03 at 100 ms, P> 0.5) or +40 mV (0.76 ± 0.03vs.0.77 ± 0.02 at 50 ms, P> 0.5; 0.83 ± 0.02vs.0.86 ± 0.01 at 100 ms, P> 0.1).

Figure 4. Synaptic release probability was not altered in mutant VPm neurons.

A, paired-pulse responses from mutant (left traces) and wild-type VPm neurons (right traces) at P16.B, paired-pulse ratios of AMPA (left panel) or NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs (right panel) at 50 and 100 ms interpulse intervals.CandD, use-dependent blockade of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs by MK-801 (10 μm; bath application) in a mutant (C) or heterozygous control neuron (D) at P15. Left panels show the first, third, 20th, 30th and 40th evoked EPSCs after MK-801 wash in; right panels are plots of peak amplitude of evoked EPSCs over time. Stimulation was halted during MK-801 wash in.E, similar progression of MK-801 blockade in mutant (open circles) and control neurons (filled circles). For each neuron, EPSC amplitude was normalized to the first EPSC after MK-801 wash in. Each data point represents the mean from 9 mutant neurons or 14 control neurons.

Next we assessed the release probability using the non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801. Experiments were performed with AC1-KO, wild-type and heterozygous littermates at P14–16. The VPm neurons were held at +40 mV, and EPSCs were evoked every 10 s in the presence of the selective AMPA receptor antagonist, NBQX (2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione, 5 μm). After obtaining baseline responses, stimulation was halted and MK-801 (10 μm) was applied through bath perfusion. After 10 min application (time to reach equilibrium in the recording chamber), stimulation was resumed. As illustrated in Fig. 4C (mutant) and D (control), the amplitude of EPSCs recorded at +40 mV decreased in a use-dependent manner in the presence of MK-801. The progression of MK-801 blockade was comparable between mutant and control neurons (Fig. 4E), and was fitted to a double-exponential function. The weighted constants were 10.6 ± 0.7 stimulations for mutant cells (n = 9) and 10.8 ± 0.5 stimulations for control cells (n = 14;P> 0.5). There was no difference between heterozygous and wild-type neurons in the weighted constant (10.6 ± 0.5vs.11.0 ± 0.9;P> 0.4). Together, these results indicate that the release probability at VPm relay synapses was not altered in AC1-KO mice.

Experience-dependent plasticity is impaired in AC1-KO mice

Experience-dependent plasticity plays a central role in developmental refinement of neuronal circuits and in learning and memory. The Ca2+ sensitivity of AC1 makes it an interesting candidate for mediating activity-dependent changes in synaptic connectivity. In the PrV–VPm pathway of mice, sensory deprivation starting at P12–13 causes a halt in synapse elimination and strengthening (Wang & Zhang, 2008). We examined the effects of sensory deprivation at the PrV–VPm synapse in AC1-KO mice and WT littermates. Sensory deprivation was done at P13 by plucking all large whiskers, and recordings were performed at P16–17. The results were compared with those obtained at P16–17 from WT and AC1-KO mice that had not undergone whisker deprivation (untreated). In WT mice, whisker deprivation disrupted synaptic refinement in VPm neurons (Fig. 5A–C, n = 20 cells from 5 mice). The proportion of neurons receiving a single PrV input reduced from 85% in untreated mice to 50% in deprived mice (Fig. 5B;P< 0.02, χ2 test), while the mean number of inputs per cell increased in deprived mice (1.60 ± 0.15 for deprivedvs.1.19 ± 0.11 for untreated;P< 0.05, Mann–WhitneyUtest). The AMPAR/NMDAR ratio was also reduced in VPm neurons of deprived mice (1.28 ± 0.07, n = 20 for deprivedvs.2.10 ± 0.15n = 16 for untreated; Fig. 6C;P< 0.0001). These results from WT mice are consistent with previous findings obtained from B6 mice (Wang & Zhang, 2008). In AC1-KO mice, however, whisker deprivation failed to produce any effects on synaptic connectivity (Fig. 5D–F). Whisker deprivation starting at P13 had no effects on the percentage of neurons receiving single or multiple inputs (Fig. 5E;P> 0.7, χ2 test), the mean number of inputs per cell (1.27 ± 0.13 for deprivedvs.1.20 ± 0.12 for untreated;P> 0.7) or the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio (Fig. 5F; 1.13 ± 0.13, n = 15 for deprivedvs.1.05 ± 0.06, n = 15 for untreated;P> 0.2).

Figure 5. Sensory deprivation disrupts synaptic connectivity in thalamus of normal but not AC1-KO mice.

A–Cwere obtained using WT mice.A, synaptic responses in a WT neuron recorded at P16 following whisker deprivation starting at P13.B, distributions of neurons with numbers of inputs for whisker deprived (filled columns) and untreated neurons (grey columns).C, the AMPAR/NMDAR for the whisker-deprived (filled columns) and untreated group (grey columns). **P< 0.001, Mann–WhitneyUtest.D–Fshow the equivalent results obtained using AC1-KO mice. For both the WT and the AC1-KO group, data for untreated groups (B, C, EandF) are the same as those presented in Figs 1C and 2A (P16–17, WT and AC1-KO).

Figure 6. Sensory deprivation reduces synaptic strength in the thalamus of normal but not AC1-KO mice.

A–Cwere obtained from WT mice aged P14.A, EPSCs recorded at +40 and –70 mV from a neuron in deprived VPm (left panel) and another in spared VPm (right panel). Whisker deprivation was performed on one side at P13, and recordings were obtained from both sides.B, the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio of EPSCs. **P< 0.005, Mann–WhitneyUtest.C, the peak amplitude of AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated EPSCs. *P< 0.01, Mann–WhitneyUtest.D–Fshow the equivalent data obtained from AC1-KO mice at P14.

Whisker deprivation causes a rapid reduction in AMPAR EPSCs at the PrV–VPm synapse in B6 mice (Wang & Zhang, 2008). We performed whisker deprivation at P13 on one side of the snout, and recorded VPm neurons from either side of the brain at P14. In WT mice, whisker deprivation caused a significant reduction of AMPAR EPSCs in VPm neurons in the contralateral (deprived) side of the brain compared with VPm neurons in the ipsilateral (spared) side (Fig. 6A–C). Consistent with the results obtained in B6 mice, the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio was significantly smaller in deprived VPm neurons (1.07 ± 0.13, n = 9 for deprivedvs.1.76 ± 0.07, n = 10 for spared; Fig. 6B;P< 0.005), with a selective reduction in AMPAR EPSCs (931 ± 103 pA for deprivedvs.1537 ± 176 pA for spared;P< 0.01), but not NMDAR EPSCs (922 ± 124 pA for deprivedvs.885 ± 112 pA for spared; Fig. 6C;P> 0.3). In contrast to the results obtained in WT mice, whisker deprivation starting at P13 in AC1-KO mice had no effects on synaptic properties measured at P14 (Fig. 6D–F). The AMPAR/NMDAR ratio was 1.13 ± 0.06 (n = 9) for deprived and 1.01 ± 0.09 (n = 8) for spared (Fig. 6E;P> 0.2). The amplitude of AMPAR EPSCs was 935 ± 158 pA for deprived and 988 ± 132 pA for spared (Fig. 6F;P> 0.5). The amplitude of NMDAR EPSCs was 825 ± 144 pA for deprived and 992 ± 101 pA for spared (Fig. 6F;P> 0.5). Together, these results indicate that experience-dependent plasticity is impaired at the PrV–VPm synapse in AC1-KO mice.

Discussion

The present studies demonstrate that AC1 is not required for the elimination of redundant synapses in the PrV-to-VPm pathway, but is essential for the maturation of remaining synapses. The developmental decline of relay inputs occurs normally in VPm neurons of AC1-KO mice. In contrast, deletion of AC1 selectively reduces AMPAR-mediated synaptic responses at VPm relay synapses. We also provide evidence that AC1 plays an important role in experience-dependent plasticity during development. Deletion of AC1 abolishes the effects of sensory deprivation on the connectivity of VPm relay synapses. Together, these results support the role of AC1 in activity-dependent strengthening of immature synapses.

Role of AC1 in the elimination of redundant synapses

The initial evidence for the role of AC1 in the development of neural circuits came from studies of thebarrelless(brl) mutation that causes the loss of AC1 function (Abdel-Majid et al. 1998). Mice homozygous for thebrlmutation fail to develop barrel-like patterns in layer IV of the somatosensory cortex. Arborizations of a single thalamocortical axon, which are confined to a single cortical barrel in normal mice, occupy a larger area in layer IV ofbrlmice (Welker et al. 1996; Gheorghita et al. 2006). However, as these studies were performed in adult mice, it was not clear whether AC1 is involved in the formation or maintenance of whisker-specific projections of thalamocortical axons.

Studies in the visual system of AC1 mutant mice provided additional insights into the role of AC1 in neural circuit development. Eye-specific segregation of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons was disrupted in the lateral geniculate nucleus ofbrlmice. Likewise, the projection from the RGC to the superior colliculus showed less refined retinotopic maps inbrlmice even at early stages of pattern formation (Ravary et al. 2003). More recent studies using organotypic cultures have shown that AC1 in RGCs is required for ephrin-mediated retraction of RGC axons (Nicol et al. 2006). Together, these results establish that AC1 has an essential role in the developmental remodelling of RGC axons.

Given the results in the barrel cortex and the visual pathways, it came as a surprise that the elimination of redundant inputs in VPm neurons proceeds normally in AC1-KO mice. The number of relay inputs connecting each VPm neuron was not different between mutant and WT mice at three different stages of the remodelling process (Fig. 1). One possibility may be that the somatosensory thalamus, unlike the other structures, does not require AC1 for neural circuit remodelling. The fact that whisker-specific patterns are less refined in the VPm of bothbrland AC1-KO mice argues against this possibility (Welker et al. 1996; Iwasato et al. 2008). Alternatively, AC1 may have different roles in map formation and fine-tuning of synaptic circuits. As whisker-specific maps are established in the VPm by P5 in the mouse, the extensive elimination of redundant inputs during the second week is therefore part of a fine-tuning process that serves to establish a higher degree of specificity within a single barreloid. It is possible that AC1 is required for signalling of molecular cues involved in map formation, but dispensable for fine-tuning of synaptic circuits at the single-cell level.

Adenylate cyclase 1 promotes synaptic strengthening

The maturation of glutamatergic synapses in the vertebrate brain is characterized by concomitant changes of both AMPA and NMDA receptors (Feldman & Knudsen, 1998). In the neonate, glutamatergic synapses contain mostly NMDARs, with few or no functional AMPA receptors (Isaac et al. 1997). The number of AMPA receptors at the postsynaptic site increases rapidly during early life, while synaptic NMDA receptors undergo changes in subunit composition (Crair & Malenka, 1995; Wu et al. 1996; Tovar & Westbrook, 1999; Lu et al. 2001). Consistent with previous studies in the barrel cortex of AC1 mutants (Lu et al. 2003), we found that the deletion of AC1 selectively reduces AMPAR EPSCs at the VPm relay synapse. Both the maximal AMPAR EPSCs and evoked quantal events mediated by AMPARs were reduced in AC1-KO neurons. In contrast, the maximal NMDAR EPSCs were not affected by the deletion of AC1. The reduction of AMPA receptor function in AC1-KO VPm neurons became larger during development (Fig. 2B). These findings indicate that AC1 is required for the developmental upregulation of AMPA receptors at the synapse. Recent studies showed that cortex-specific deletion of AC1 leads to a reduction of AMPAR-mediated EPSCs at thalamocortical synapses in cortical layer 4 neurons (Iwasato et al. 2008), suggesting that postsynaptic AC1 signalling is implicated in upregulation of AMPA receptors in the cortex. In our case, however, presynaptic roles of AC1 should also be considered. Each PrV axon makes a large number of synaptic contacts with its target neuron in the VPm (Peschanski et al. 1985; Williams et al. 1994). Although deletion of AC1 had no effect on the number of inputs or the release probability at VPm relay synapses, a reduction in the number of synaptic contacts on individual neurons would lead to a decrease in EPSCs. This possibility seems unlikely, however, because NMDAR EPSCs were not altered in AC1-KO mice. Another possibility is that deletion of AC1 may reduce the quantal content in presynaptic terminals, and this reduction will preferentially affect AMPAR EPSCs because of the lower affinity of AMPA receptors for glutamate (Lisman et al. 2007). To our knowledge, there is no evidence for cAMP in regulating quantal content at glutamatergic synapses in vertebrates. Furthermore, a reduction in quantal content cannot fully account for the large and selective decrease of evoked AMPAR EPSCs.

How AC1 regulates the number of synaptic AMPA receptors remains unclear. Previous studies in cultured neurons have shown that activation of protein kinase A (PKA) promotes cell-surface expression of AMPA receptors through direct phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunits (Esteban et al. 2003; Man et al. 2007). Native AMPARs are heteropentamers composed of four subunits GluA1 through GluA4 (glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA1 through AMPA4). In the barrel cortex ofbrlmice, the reduction of AMPAR EPSCs is associated with a decrease of phosphorylated GluA1 (Lu et al. 2003). In the VPm of the mouse, GluA3 and GluA4 are highly expressed, GluA2 is expressed at a lower level and GluA1 is not detectable (Mineff & Weinberg, 2000; Allen Brain Atlas: http://developingmouse.brain-map.org/). Consistent with expression studies, we have found that VPm relay synapses contain few GluA2 subunits (Wang & Zhang, 2008). Using quantitative RT-PCR, we found that AC1 deletion did not alter the transcript level of GluA3 or GluA4 in the thalamus (data not shown), suggesting that AC1 is implicated in membrane trafficking of GluA3- or GluA4-containing receptors. Future studies are required to determine the role of GluA3 and GluA4 phosphorylation in AC1-mediated upregulation of synaptic AMPA receptors in the thalamus.

Adenylate cyclase 1 plays an important role in experience-dependent synaptic plasticity

Experience-dependent modification of synaptic connectivity plays a key role in neural circuit development. Early life experience, through neuronal activity, regulates elimination and strengthening of immature synapses (Lichtman & Colman, 2000; Ruthazer & Cline, 2004). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying experience-dependent plasticity remain poorly understood. Activity-dependent regulation of AMPA receptor phosphorylation plays a critical role in long-term synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum and hippocampus, and in learning and memory (Chung et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2003; Steinberg et al. 2006). Synaptic transmission at excitatory synapses in layer 2/3 of the somatosensory cortex is regulated by sensory experience during early life (Stern et al. 2001; Allen et al. 2003), and this form of experience-dependent plasticity may be associated with changes in AMPA receptor subunit composition (Clem & Barth, 2006; Clem et al. 2010). The calcium sensitivity and early presence of AC1 in the developing brain makes it an interesting candidate for experience-dependent mechanisms. Calcium entry through synaptic NMDA receptors and/or voltage-gated calcium channels during a period of synaptic activity may be sufficient to activate AC1 in immature neurons. The present study has provided direct evidence supporting the role of AC1 in experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in the developing brain. We have found that a brief period of whisker deprivation disrupts synapse elimination and synaptic properties in VPm neurons of WT mice but not AC1-KO mice. Consistent with previous studies in B6 mice (Wang & Zhang, 2008), sensory deprivation during the critical period (P12–13) in wild-type mice disrupted the elimination of redundant inputs and delayed the strengthening of the remaining synapses in VPm neurons. In contrast, sensory deprivation in AC1-KO mice had no effect on the number or strength of synaptic inputs (Figs 5 and 6). It is interesting to note that whisker deprivation during the same period also induces plasticity in layer 2/3 of the barrel cortex in rodents (Lendvai et al. 2000; Stern et al. 2001), indicating that sensory experience at this age is critical for the fine-tuning of multiple synapses of the whisker sensory pathway in rodents.

Our findings suggest that AC1 is required for experience-dependent plasticity at VPm relay synapses. A number of caveats, however, should be considered. First, the reduction of synaptic AMPA receptor-mediated responses in AC1-KO mice may impede synaptic transmission along the whisker sensory pathway so that experience-dependent activity is already low in non-deprived mice. This possibility seems unlikely because AC1 mutant mice showed normal evoked responses in the barrel cortex despite a reduction of whisker specificity, indicating that synaptic transmission along the sensory pathway was not significantly altered in these mice (Welker et al. 1996). However, it is possible that experience-dependent plasticity requires normal synaptic strength and that AC1 plays an indirect role by weakening the synapse. This possibility may be examined by reducing the number of AMPA receptors in the synapse during the critical period. Second, it is not clear why sensory deprivation failed to disrupt synapse elimination in AC1-KO mice. At first glance, this result seems to suggest that AC1 is required for experience-dependent synapse elimination. However, this idea is not consistent with the finding that elimination of redundant inputs occurs normally in AC1-KO mice. One explanation may be that constitutive knockout of AC1 causes compensatory changes in molecular pathways involved in synapse elimination. Indeed, previous studies have shown that chronic sensory deprivation throughout early life does not significantly alter connectivity at either visual or somatosensory relay synapses in the thalamus (Arsenault & Zhang, 2006; Hooks & Chen, 2006). This possibility may be examined by timed deletion of AC1 during early life. Lastly, the fact that AC1 is expressed in both pre- and postsynaptic neurons (PrV and VPm, respectively) raises a question about the role of AC1 at the two loci in experience-dependent plasticity. The retraction of RGC axons requires AC1 in RGC but not in postsynaptic lateral geniculate nucleus neurons (Nicol et al. 2006). In contrast, selective deletion of AC1 in the cortex is sufficient to cause a reduction of AMPAR EPSCs at thalamocortical synapses (Iwasato et al. 2008). Thus, AC1 signalling in pre- and postsynaptic neurons may have distinct roles in different aspects of experience-dependent plasticity at the synapse.

In conclusion, our results show that AC1 is essential for synaptic strengthening, but is dispensable for elimination of redundant synaptic inputs in the somatosensory thalamus. Adenylate cyclase 1 is selectively involved in the late phase of synaptic refinement and is required for experience-dependent strengthening of synapses. These data support the role of cAMP-mediated signalling in experience-dependent plasticity in the developing brain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenzhi Sun, Da-Ting Lin and members of Zhang laboratory for comments on the manuscript, and Guy Chan for performing some preliminary studies. This work was supported by NIH grant NS064013 (to Z.-w.Z.). The authors have no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AC1

adenylate cyclase 1

- AMPAR

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor

- Brl

barrelless

- KO

knockout

- NMDAR

N-methyl d-aspartate receptor

- PPR

paired-pulse ratio

- PrV

principal sensory trigeminal nucleus

- RGC

retinal ganglion cell

- VPm

ventral posteromedial nucleus of the thalamus

- WT

wild-type

Author contributions

H.W., H.L. and Z.-w.Z. performed experiments and analysis and wrote the paper. D.R.S. contributed reagents and conducted some preliminary experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Abdel-Majid RM, Leong WL, Schalkwyk LC, Smallman DS, Wong ST, Storm DR, Fine A, Dobson MJ, Guernsey DL, Neumann PE. Loss of adenylyl cyclase I activity disrupts patterning of mouse somatosensory cortex. Nat Genet. 1998;19:289–291. doi: 10.1038/980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen CB, Celikel T, Feldman DE. Long-term depression induced by sensory deprivation during cortical map plasticityin vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:291–299. doi: 10.1038/nn1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault D, Zhang ZW. Developmental remodelling of the lemniscal synapse in the ventral basal thalamus of the mouse. J Physiol. 2006;573:121–132. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ, Steinberg JP, Huganir RL, Linden DJ. Requirement of AMPA receptor GluR2 phosphorylation for cerebellar long-term depression. Science. 2003;300:1751–1755. doi: 10.1126/science.1082915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clem RL, Anggono V, Huganir RL. PICK1 regulates incorporation of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors during cortical synaptic strengthening. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6360–6366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6276-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clem RL, Barth A. Pathway-specific trafficking of native AMPARs by in vivo experience. Neuron. 2006;49:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crair MC, Malenka RC. A critical period for long-term potentiation at thalamocortical synapses. Nature. 1995;375:325–328. doi: 10.1038/375325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban JA, Shi SH, Wilson C, Nuriya M, Huganir RL, Malinow R. PKA phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunits controls synaptic trafficking underlying plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:136–143. doi: 10.1038/nn997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DE, Knudsen EI. Experience-dependent plasticity and the maturation of glutamatergic synapses. Neuron. 1998;20:1067–1071. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson GD, Storm DR. Why calcium-stimulated adenylyl cyclases? Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:271–276. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00010.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghita F, Kraftsik R, Dubois R, Welker E. Structural basis for map formation in the thalamocortical pathway of the barrelless mouse. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10057–10067. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1263-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Kano M. Functional differentiation of multiple climbing fiber inputs during synapse elimination in the developing cerebellum. Neuron. 2003;38:785–796. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks BM, Chen C. Distinct roles for spontaneous and visual activity in remodeling of the retinogeniculate synapse. Neuron. 2006;52:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JT, Crair MC, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Silent synapses during development of thalamocortical inputs. Neuron. 1997;18:269–280. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasato T, Inan M, Kanki H, Erzurumlu RS, Itohara S, Crair MC. Cortical adenylyl cyclase 1 is required for thalamocortical synapse maturation and aspects of layer IV barrel development. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5931–5943. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0815-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M, Hashimoto K. Synapse elimination in the central nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Takamiya K, Han JS, Man H, Kim CH, Rumbaugh G, Yu S, Ding L, He C, Petralia RS, Wenthold RJ, Gallagher M, Huganir RL. Phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit is required for synaptic plasticity and retention of spatial memory. Cell. 2003;112:631–643. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendvai B, Stern EA, Chen B, Svoboda K. Experience-dependent plasticity of dendritic spines in the developing rat barrel cortexin vivo. Nature. 2000;404:876–881. doi: 10.1038/35009107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman JW, Colman H. Synapse elimination and indelible memory. Neuron. 2000;25:269–278. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Raghavachari S, Tsien RW. The sequence of events that underlie quantal transmission at central glutamatergic synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrn2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HC, Butts DA, Kaeser PS, She WC, Janz R, Crair MC. Role of efficient neurotransmitter release in barrel map development. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2692–2703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3956-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HC, Gonzalez E, Crair MC. Barrel cortex critical period plasticity is independent of changes in NMDA receptor subunit composition. Neuron. 2001;32:619–634. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HC, She WC, Plas DT, Neumann PE, Janz R, Crair MC. Adenylyl cyclase I regulates AMPA receptor trafficking during mouse cortical ‘barrel’ map development. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:939–947. doi: 10.1038/nn1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, O'Leary DD. Axon retraction and degeneration in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:127–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man HY, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Huganir RL. Regulation of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor trafficking through PKA phosphorylation of the Glu receptor 1 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3579–3584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611698104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineff EM, Weinberg RJ. Differential synaptic distribution of AMPA receptor subunits in the ventral posterior and reticular thalamic nuclei of the rat. Neuroscience. 2000;101:969–982. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol X, Muzerelle A, Bachy I, Ravary A, Gaspar P. Spatiotemporal localization of the calcium-stimulated adenylate cyclases, AC1 and AC8, during mouse brain development. J Comp Neurol. 2005;486:281–294. doi: 10.1002/cne.20528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol X, Muzerelle A, Rio JP, Métin C, Gaspar P. Requirement of adenylate cyclase 1 for the ephrin-A5-dependent retraction of exuberant retinal axons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:862–872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3385-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschanski M, Roudier F, Ralston HJ, 3rd, Besson JM. Ultrastructural analysis of the terminals of various somatosensory pathways in the ventrobasal complex of the rat thalamus: an electron-microscopic study using wheatgerm agglutinin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase as an axonal tracer. Somatosens Res. 1985;3:75–87. doi: 10.3109/07367228509144578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravary A, Muzerelle A, Hervé D, Pascoli V, Ba-Charvet KN, Girault JA, Welker E, Gaspar P. Adenylate cyclase 1 as a key actor in the refinement of retinal projection maps. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2228–2238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02228.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthazer ES, Cline HT. Insights into activity-dependent map formation from the retinotectal system: a middle-of-the-brain perspective. J Neurobiol. 2004;59:134–146. doi: 10.1002/neu.10344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg JP, Takamiya K, Shen Y, Xia J, Rubio ME, Yu S, Jin W, Thomas GM, Linden DJ, Huganir RL. Targeted in vivo mutations of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 and its interacting protein PICK1 eliminate cerebellar long-term depression. Neuron. 2006;49:845–860. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern EA, Maravall M, Svoboda K. Rapid development and plasticity of layer 2/3 maps in rat barrel cortex in vivo. Neuron. 2001;31:305–315. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar KR, Westbrook GL. The incorporation of NMDA receptors with a distinct subunit composition at nascent hippocampal synapsesin vitro. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4180–4188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-04180.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Storm DR. Calmodulin-regulated adenylyl cyclases: cross-talk and plasticity in the central nervous system. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:463–468. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhang ZW. A critical window for experience-dependent plasticity at whisker sensory relay synapse in the thalamus. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13621–13628. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4785-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker E, Armstrong-James M, Bronchti G, Ourednik W, Gheorghita-Baechler F, Dubois R, Guernsey DL, Van der Loos H, Neumann PE. Altered sensory processing in the somatosensory cortex of the mouse mutant barrelless. Science. 1996;271:1864–1867. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MN, Zahm DS, Jacquin MF. Differential foci and synaptic organization of the principal and spinal trigeminal projections to the thalamus in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:429–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Malinow R, Cline HT. Maturation of a central glutamatergic synapse. Science. 1996;274:972–976. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZL, Thomas SA, Villacres EC, Xia Z, Simmons ML, Chavkin C, Palmiter RD, Storm DR. Altered behavior and long-term potentiation in type I adenylyl cyclase mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:220–224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H, Barth AL, Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. A developmental switch in the signalling cascades for LTP induction. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:15–16. doi: 10.1038/nn985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]