Background: The cAMP/PKA pathway regulates BDNF transcription via nuclear RACK1.

Results: We identified 14-3-3ζ as a RACK1-binding protein. Disruption of RACK1/14-3-3 interaction or knockdown of 14-3-3ζ levels inhibits RACK1 nuclear translocation and BDNF transcription.

Conclusion: The 14-3-3ζ·RACK1 complex is necessary for RACK1 nuclear translocation and BDNF transcription.

Significance: BDNF transcription is regulated by RACK1·14-3-3ζ complex.

Keywords: Adaptor Proteins, Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), Protein Kinase A (PKA), Protein Motifs, Scaffold Proteins, 14-3-3, Neurotrophic Factor, RACK1, Translocation

Abstract

RACK1 is a scaffolding protein that spatially and temporally regulates numerous signaling cascades. We previously found that activation of the cAMP signaling pathway induces the translocation of RACK1 to the nucleus. We further showed that nuclear RACK1 is required to promote the transcription of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Here, we set out to elucidate the mechanism underlying cAMP-dependent RACK1 nuclear translocation and BDNF transcription. We identified the scaffolding protein 14-3-3ζ as a direct binding partner of RACK1. Moreover, we found that 14-3-3ζ was necessary for the cAMP-dependent translocation of RACK1 to the nucleus. We further observed that the disruption of RACK1/14-3-3ζ interaction with a peptide derived from the RACK1/14-3-3ζ binding site or shRNA-mediated 14-3-3ζ knockdown inhibited cAMP induction of BDNF transcription. Together, these data reveal that the function of nuclear RACK1 is mediated through its interaction with 14-3-3ζ. As RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ are two multifunctional scaffolding proteins that coordinate a wide variety of signaling events, their interaction is likely to regulate other essential cellular functions.

Introduction

By means of protein/protein interactions, scaffolding proteins are central components of the cell signaling network that integrate and control the propagation of extracellular signals (1–4). Specifically, scaffolding proteins allow the formation of preassembled or signal-dependent multiprotein complexes that contribute to the accuracy of the spatiotemporal processing and transmission of a signal (1–4). In addition, an appropriate transmission of an intracellular signal can be achieved by the subcellular compartmentalization of signaling proteins that typically requires post-translational modification and/or the association with scaffolding proteins (1–4).

RACK1 is a highly conserved scaffolding protein originally identified as a βII protein kinase C (PKC) anchoring protein (5) and was later reported to bind a wide range of signaling proteins, including kinases, phosphatases, transcription factors, and the cytoplasmic domain of membrane proteins (6). RACK1 belongs to the tryptophan-aspartate (WD-40) repeat family that folds into a β-propeller shape (6, 7). This globular structure is composed of seven blades (WD1–7 regions), each containing a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, connected by loops (6, 8, 9). These compact and multisided structural features allow RACK1 to bind proteins through a wide array of protein domains (6).

By controlling the interaction network between these different families of signaling proteins, RACK1 regulates a wide range of discrete signaling events at the level of several subcellular compartments such as the cytosol (6, 10), the endoplasmic reticulum (11), and the nucleus (12, 13). In addition, translocation of RACK1 from one subcellular location to another has been shown to mediate various cellular responses following a stimulus. For instance, RACK1 accompanies PKCβII to its site of action in response to its activation (14). Furthermore, upon cellular stress such as hypoxia or heat shock, RACK1 is sequestered into cytoplasmic stress granules, preventing the activation of a stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which in turn leads to cell survival instead of cell apoptosis (15). Moreover, we previously found that activation of the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway in various types of cells, including neurons, induces RACK1 translocation to the nucleus, subsequently leading to the gene transcription of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)4 (12, 16). We further showed that activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway results in the association of RACK1 with the promoter IV region of the BDNF gene, leading to an increase in exon IV-specific BDNF transcription (12). This process is particularly important in the nervous system because BDNF is essential for neuronal development, survival, and function as well as synaptic plasticity (17, 18). Likewise, the cAMP/PKA pathway, a signaling cascade activated by peptides, hormones, and neurotransmitters, contributes to the regulation of various neuronal functions (19, 20). In the present study, we therefore set out to identify the mechanism by which RACK1, a focal node connecting the cAMP/PKA and BDNF signaling pathways, translocates to the nucleus in response to the activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway to regulate BDNF transcription.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Anti-RACK1 (sc-17754), anti-14-3-3ζ (sc-1019), anti-pan14-3-3 (sc-629), and anti-phospho-ERK (sc-7976-R) antibodies as well as all the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-phospho-GSK3β (catalog number 9323), anti-phospho-S6 (catalog number 2211), anti-GST, and anti-CREB (catalog number 9121) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-actin antibody (catalog number A5316), DNase (catalog number AMP-D1), forskolin, H-89, bisindolylmaleimide I hydrochloride, and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures 1 and 2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The protease inhibitor mixture and isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside were purchased from Roche Applied Science. Trypsin, the reverse transcription system, and 2× PCR Master Mix were purchased from Promega. Primers for PCR were synthesized by Sigma-Genosys. Amylose resin and λ-phosphatase were from New England BioLabs. Thrombin, glutathione-Sepharose 4B, Deep PurpleTM total protein stain, and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents were from GE Healthcare. NuPAGE® Bis-Tris precast gels and recombinant protein G-agarose were from Invitrogen. Peptides were synthesized by Anaspec, Inc. The purity of the peptides was greater than 90%, and their integrity was analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Cell Culture

SHSY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) supplemented with non-essential amino acid solution. Cells were incubated in a low serum medium containing 1% FBS for at least 24 h before treatment.

Preparation of Primary Rat Hippocampal Neurons

A litter of Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan) was obtained on either the day of birth or the 1st postnatal day (postnatal days 0–1), and rats were killed by decapitation. The hippocampi were collected, pooled, and digested in a solution containing 20 units/ml papain (Worthington) for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were mechanically dissociated by pipette trituration and spun down for 5 min at 500 × g, and digestion was stopped by brief incubation with a trypsin inhibition solution (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were plated on poly-d-lysine-treated plates. On day 1, half of the medium was changed, 10 μm cytosine arabinoside was added to inhibit growth of glial cells, and half of the medium was changed again 3 days later. Neurons were then maintained in culture for 3 weeks in Neurobasal-A medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with B-27 and GlutaMAX supplements (Invitrogen) as well as penicillin and streptomycin.

RACK1 Immunoprecipitation and Gel Staining

SHSY5Y cells were treated with 10 μm forskolin (FSK) for 30 min and then lysed in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, and protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures). Lysate was precleared and incubated with RACK1 antibody or IgG. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, recombinant protein G-agarose was added, and the mixture was further incubated at 4 °C for 2 h. The agarose resin was extensively washed with IP buffer, and immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted in loading buffer (2% SDS, 23% β-mercaptoethanol, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.1% bromphenol blue) and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Deep Purple total protein stain according to the provider's instructions and scanned with a TyphoonTM scanner (GE Healthcare) (excitation, 532 nm; emission, 610BP filter).

Mass Spectrometry Identification of Proteins

The whole lanes (IgG versus RACK1) of interest were manually excised from a representative gel and cut into small pieces. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed by the University of California, San Francisco Sandler-Moore Mass Spectrometry Core Facility. Proteins were subjected to trypsin digestion, and mixtures of proteolytic peptides were separated by nano-LC utilizing an Eksigent two-dimensional LC NanoLC system (Eksigent/Applied Biosystems Sciex) interfaced with a QStar XL mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems Sciex). ProteinPilotTM Software 4.0 that utilizes the ParagonTM algorithm (Applied Biosystems Sciex) was used for peak detection, mass peak list generation, and database searches. Protein identifications based on multiple peptides were accepted using a cutoff score of 1.69897 that represented more than 98% confidence. However, in cases of identities based on a single peptide, a cutoff score of 2.0 representing more than 99% confidence was used. Additional information is provided in the supplemental Methods.

Western Blot Analyses

Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBS-T) and then incubated overnight at 4 °C in the blocking solution including the appropriate antibody. After extensive washes with TBS-T, bound primary antibodies were detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and visualized by ECL. The optical density of the relevant immunoreactive band was quantified using the NIH Image 1.63 program.

Recombinant Proteins

Maltose-binding protein (MBP), MBP-RACK1, and glutathione S-transferase (GST) were described previously (21, 22). GST-14-3-3ζ and GST-14-3-3θ constructs (containing a thrombin cleavage site flanked by GST and 14-3-3ζ or 14-3-3θ sequences) were generously obtained from Yun-Cai Liu (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology). Recombinant proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli by induction with 1.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 4 h, and cells were lysed by successive freeze/thaw cycles and sonication.

Affinity Column Assay

Crude extracts of MBP fusion proteins were incubated with 1 ml of prewashed amylose suspension, and the column was washed extensively with column buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.002% sodium azide, and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol). One milligram of SHSY5Y lysate at 1 μg/μl in IP buffer was applied to the column for 1 h at room temperature. After extensive washes with a solution containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% polyethylene glycol (Mr 15,000–20,000), 1.2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.2 m NaCl, bound proteins were eluted three times with 500 μl of column buffer supplemented with 50 mm maltose and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were stained with colloidal Coomassie Blue (G-250) as described previously (23) or further analyzed by Western blot.

GST Pulldown

GST pulldown was performed in 1 ml of IP buffer containing 500 μg of SHSY5Y lysate and 10 μg of GST or GST-14-3-3ζ immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, beads were extensively washed with IP buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with loading buffer, boiled for 5 min at 95 °C, and resolved by SDS-PAGE.

Direct Interaction between RACK1 and 14-3-3 Proteins

Thrombin cleavage of GST-14-3-3ζ or GST-14-3-3θ immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose was carried out with 50 units of thrombin protease in 1 ml of thrombin buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 8.7, 150 mm NaCl, and 2.5 mm CaCl2) at room temperature as indicated by the provider. Cleaved 14-3-3ζ or 14-3-3θ was collected in the supernatant, and the digestion was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by colloidal Coomassie Blue staining. Ten micrograms of cleaved 14-3-3ζ or 14-3-3θ in 1 ml of IP buffer was applied to MBP or MBP-RACK1 immobilized on amylose resin. After a 2-h incubation at room temperature, amylose resin was extensively washed as described above. Bound proteins were eluted with loading buffer or 50 mm maltose and analyzed by Western blot.

Phosphatase Assay

Five hundred micrograms of SHSY5Y lysate at a concentration of 1 μg/μl in 1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 1.5 mm MnCl2 were incubated for 30 min at 30 °C with 2000 units of λ-phosphatase as indicated by the provider. Ten microliters of the reaction solution were loaded for SDS-PAGE to confirm the efficiency of protein dephosphorylation and analyzed by Western blot using phosphospecific antibodies. The rest of the sample was used to immunoprecipitate RACK1 as described above.

Preparation of Recombinant Adenoviruses

Two recombinant adenoviruses carrying the shRNA sequences to down-regulate the level of 14-3-3ζ were constructed as described previously (12, 24). Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-a (5′-ACG GTT CAC ATT CCA TTA T-3′) targeting the 3′ non-coding region of 14-3-3ζ mRNA was shown previously to specifically knock down 14-3-3ζ protein (25). The sequence of Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-b was 5′-AGT TCT TGA TCC CCA ATG C-3′, which targets the open reading frame of 14-3-3ζ and was designed using iRNAi software. A recombinant adenovirus carrying a non-related 19-nucleotide sequence, 5′-ATG AAC GTG AAT TGC TCA A-3′ (12, 26), was also constructed as a control. Viruses were amplified in HEK293 cells, then purified using the Adeno-XTM Maxi Purification kit, and titered with the Adeno-X Rapid Titer kit (Clontech). Viruses were used at a concentration of 1 × 106 infection units/ml.

Reverse Transcription and Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent, and 1 μg was used for reverse transcription using a reverse transcription system at 42 °C for 30 min followed by 6 min at 95 °C. Gene expression was analyzed by PCR with temperature cycling parameters consisting of initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min followed by cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 2 min, and a final incubation at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were resolved on a 1.8% agarose gel in Tris/acetic acid/EDTA buffer with 0.25 μg/ml ethidium bromide and photographed by Eagle Eye II (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The images were digitally scanned, and the signals were quantified by densitometry using the NIH Image 1.63 program.

For RT-PCR from human SHSY5Y cell samples, the following primers were used as described (12): BDNF-F, 5′-CTT TGG TTG CAT GAA GGC TGC-3′; BDNF-R, 5′-GTC TAT CCT TAT GAA TCG CCA G-3′; actin-F, 5′-TCA TGA AGT GTG ACG TTG ACA TC-3′; actin-R, 5′-AGA AGC ATT TGC GGT GGA CGA TG-3′; GAPDH-F, 5′-TGA AGG TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG GC-3′; and GAPDH-R, 5′-CAT GTA GGC CAT GAG GTC CAC CAC-3′. For RT-PCR from rat hippocampal neuron samples, the following primers were used: BDNF-F, 5′-TTG AGC ACG TGA TCG AAG AGC-3′; BDNF-R, 5′-GTT CGG CAT TGC GAG TTC CAG-3′; 14-3-3ζ-F, 5′-TGC TGG TGA TGA CAA GAA AGG-3′; 14-3-3ζ-R, 5′-GCT TCG TCT CCT TGG GTA TCC-3′; GAPDH-F, 5′-TGA AGG TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG GC-3′; and GAPDH-R, 5′-CAT GTA GGC CAT GAG GTC CAC CAC-3′.

Spot Synthesis of Peptides and Overlay Analysis

Nitrocellulose-bound peptide arrays of RACK1-derived peptides were generated as described previously (27–29). Essentially, scanning libraries of overlapping 18-mer peptides covering the entire sequence of RACK1 were produced by automatic spot synthesis and synthesized on continuous cellulose membrane supports on Whatman 50 cellulose using Fmoc (9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl) chemistry with the AutoSpot-Robot ASS 222 (Intavis Bioanalytical Instruments). The interaction of GST or GST-14-3-3ζ with the RACK1 array was investigated by overlaying the membranes with a 10 μg/ml concentration of each recombinant protein overnight at 4 °C. Bound protein was detected by anti-GST antibodies and visualized by ECL.

Once the binding site of 14-3-3ζ on the full-length RACK1 array was determined, specific alanine-scanning substitution arrays were generated for selected peptides using the same synthesis procedure. In cases where the parent amino acid was alanine, it was substituted for aspartate. The binding of GST-14-3-3ζ to the 18-mer single mutated peptides was measured by densitometry and presented as a percentage of the binding of GST-14-3-3ζ to the control “parent” peptide (29, 30). A minimum of a 50% decrease of the binding compared with the parent peptide was applied to identify amino acids critical for the interaction.

Real Time RT-PCR Assay

Total RNA from hippocampal neurons was isolated using TRIzol reagent. Samples were treated with DNase prior to reverse transcription of 0.5 μg of RNA as described above. Each resulting cDNA sample was amplified in triplicate in a 7900 HT detection system (Applied Biosystems) by TaqMan® quantitative PCR using universal PCR Master Mix and commercially available primers from Applied Biosystems for BDNF (Gene Expression Assay Rn01484928_m1) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Gene Expression Assay Rn99999916_s1) as internal control. The thermal cycle conditions were 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min. Expression levels of BDNF and GAPDH mRNAs were quantified using the relative standard curve method (31). Specifically, standard curves were constructed for BDNF and GAPDH genes using rat primary hippocampal neuron cDNA as a template. The cycle threshold (Ct) values of BDNF and GAPDH were then plotted against the log of the relative quantity of amplified cDNA (Ct = f(log cDNArelative quantity)).

Subcellular Fractionation

Subcellular fractions were prepared as described previously (32). Briefly, cells were scraped in and washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before lysing in Buffer I (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH7.9, 10 mm KCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, and protein and phosphatase inhibitors). Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 3800 × g for 3 min, and the supernatants (cytoplasmic fraction) were saved. The pellets of nuclei were washed with Buffer I without Nonidet P-40 and suspended in a radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and protein and phosphatase inhibitors). The nuclear lysates were briefly sonicated and clarified by centrifugation at 3800 × g for 3 min, and the supernatant was used as the nuclear fraction. The integrity of the fractionation was verified by examining the distribution of the transcription factor CREB within the two fractions.

Data Analysis

Depending on the design of the experiment, data were analyzed with one-tailed unpaired t test, one-way ANOVA, or two-way ANOVA. Significant main effects and interactions of the ANOVAs were further investigated with the Newman-Keuls post hoc test or the method of contrasts (one-tailed unpaired t test). Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

Identification of 14-3-3ζ as RACK1 Binding Partner

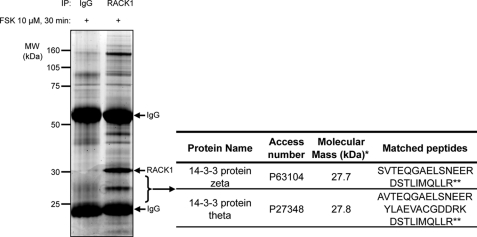

Activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway results in the nuclear translocation of RACK1 (16). As RACK1 functions by means of protein/protein interaction and does not contain a known nuclear localization signal in its amino acid sequence, we hypothesized that a binding partner may mediate its translocation to the nucleus. Therefore, a proteomics approach was implemented to identify RACK1 binding partners following activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway. We used SHSY5Y cells as a model system because we previously showed that RACK1 mediates cAMP/PKA-induced BDNF transcription in this cell line in a fashion similar to that in hippocampal and striatal neurons (12, 16, 33). SHSY5Y cells were treated with FSK, an activator of adenylyl cyclase; RACK1 was immunoprecipitated; and co-immunoprecipitated proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and revealed by Deep Purple total protein stain (34). Peptide sequences corresponding to two members of the 14-3-3 protein family, 14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3θ, were identified by tandem mass spectrometry in the RACK1 immunoprecipitate but not in the corresponding gel section representing the IgG control (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

Mass spectrometry identification of 14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3θ as binding partners of RACK1. SHSY5Y cells were treated with 10 μm FSK for 30 min and then lysed in IP buffer. RACK1 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysate, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Deep Purple to visualize proteins. Gel slices were in-gel protein-digested, and the resulting peptides were submitted to mass spectrometry (MS/MS) sequencing for protein identification. 14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3θ were identified in the RACK1 immunoprecipitate but not in the corresponding gel section representing the IgG control. Identification of 14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3θ proteins is based on matching two and three peptides, respectively. Among these peptides, one is common to both isoforms. Evidence of MS-based protein identification is provided in the supplemental material. n = 2. *, reflects DNA sequence-based amino acid composition; **, common peptide for both proteins. Access, accession.

The 14-3-3 family of proteins consists of seven isoforms that regulate the function and subcellular location of proteins by interacting mainly with phospho-serine or phospho-threonine containing motifs (35–37). In addition, 14-3-3 proteins have been reported to transit in and out of the nucleus (38, 39). Among the 14-3-3 proteins, 14-3-3ζ is widely distributed throughout the brain (40), and the isoform has been reported to display rapid nucleocytoplasmic shuttling properties (39). Thus, we tested the possibility that 14-3-3ζ contributes to RACK1 nuclear shuttling and to the induction of BDNF transcription.

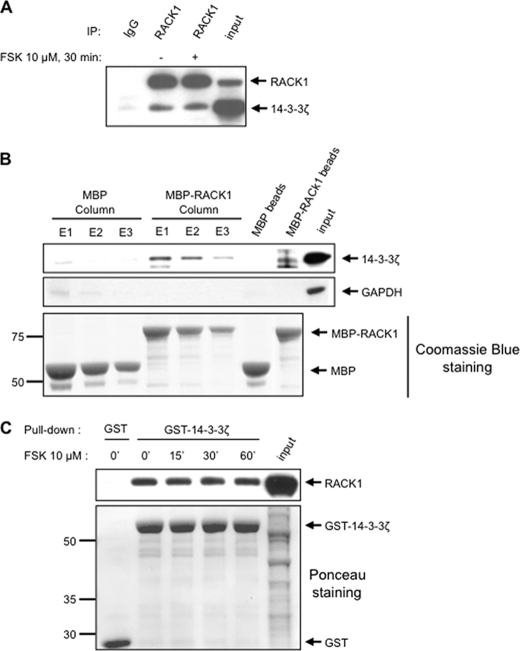

Validation of 14-3-3ζ as RACK1 Binding Partner

First, we set out to confirm the mass spectrometry identification of 14-3-3ζ as a protein that co-immunoprecipitates with RACK1 and tested whether this association was dependent on cAMP/PKA signaling. After verification that FSK treatment did not affect the global amount of both RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ in SHSY5Y cells (supplemental Fig. S2), endogenous RACK1 was immunoprecipitated from SHSY5Y cell lysate treated with vehicle or FSK, and the level of co-immunoprecipitated 14-3-3ζ was examined by Western blot analysis. We found that endogenous RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ interacted in the presence but also in the absence of cAMP/PKA pathway activation (Fig. 2A). Next, we verified that the interaction between RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ is specific. Recombinant MBP or MBP-RACK1 was immobilized on an amylose resin column and incubated with SHSY5Y lysate that was previously treated with FSK, and the association of endogenous 14-3-3ζ protein with the eluted MBP-RACK1 or MBP was determined by Western blot analysis. We observed that endogenous 14-3-3ζ bound MBP-RACK1 but not MBP (Fig. 2B, top panel). GAPDH, which was used as an additional control, did not interact with either MBP or MBP-RACK1 (Fig. 2B, middle panel). Next, we examined the association between RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ using the reciprocal interaction test. To do so, GST or recombinant 14-3-3ζ protein fused to GST was immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads and incubated with SHSY5Y lysate previously treated with vehicle or FSK, and the association of endogenous RACK1 protein with recombinant GST-14-3-3ζ was determined by Western blot analysis. In agreement with the data described above, we found that GST-14-3-3ζ, but not GST, pulled down endogenous RACK1 from SHSY5Y cell lysate in the presence but also in the absence of cAMP/PKA pathway activation (Fig. 2C, top panel). Taken together, these data indicate that the interaction between 14-3-3ζ and RACK1 is specific and constitutive.

FIGURE 2.

Validation of 14-3-3ζ as binding partner of RACK1. A, SHSY5Y cells were treated with vehicle or 10 μm FSK for 30 min and then lysed in IP buffer. RACK1 was immunoprecipitated from whole cell lysate, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Endogenous RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ were revealed by Western blot. n = 3. B, recombinant MBP and MBP-RACK1 were immobilized on an amylose resin column and incubated with SHSY5Y lysate previously treated with 10 μm FSK for 30 min. After extensive washing, bound proteins were eluted three times with 50 mm maltose (E1, E2, and E3) or with loading buffer (MBP beads and MBP-RACK1 beads). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blot. The amount of MBP and MBP-RACK1 eluted was controlled with colloidal Coomassie Blue staining. n = 2. C, recombinant GST and GST-14-3-3ζ immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose were incubated with SHSY5Y lysate previously treated with vehicle or 10 μm FSK for the indicated duration. After extensive washing, pulled down proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was first stained with Ponceau S (lower panel) and then immunoblotted with RACK1 antibody (upper panel). n = 3. ′, minutes.

Interaction between RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ Is Direct and Phosphoindependent

Next, we aimed to test whether the interaction between RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ is direct. First, we performed an in vitro binding assay in which recombinant MBP and MBP-RACK1 were immobilized on an amylose resin column and then incubated with purified recombinant GST-14-3-3ζ. After extensive washing and elution steps, we found that recombinant MBP-RACK1, but not MBP, was eluted together with GST-14-3-3ζ (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the interaction between the two proteins is direct. To rule out the possibility that the interaction of MBP-RACK1 with GST-14-3-3ζ was due to nonspecific binding of GST to RACK1, GST was cleaved from 14-3-3ζ by thrombin treatment (Fig. 3B) prior to incubation with MBP or MBP-RACK1 immobilized on amylose resin (Fig. 3C). In agreement with the results described above, we observed that recombinant MBP-RACK1, but not MBP, was eluted together with 14-3-3ζ previously digested by thrombin (Fig. 3C). As 14-3-3θ was also identified by tandem mass spectrometry in the RACK1 immunoprecipitate (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1), we set out to determine whether this isoform also interacts with RACK1 in vitro. To do so, recombinant GST-14-3-3θ was purified, and GST was cleaved off by thrombin treatment (supplemental Fig. S3). As shown in Fig. 3D, we found that MBP-RACK1, but not MBP, bound recombinant 14-3-3θ. Taken together, these data suggest that recombinant 14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3θ isoforms interact with recombinant RACK1 via a direct protein/protein interaction.

FIGURE 3.

14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3θ directly bind to RACK1 in phosphoindependent manner. A, recombinant MBP and MBP-RACK1 were immobilized on an amylose resin column and incubated with purified recombinant GST-14-3-3ζ. After extensive washing, maltose-eluted proteins (E1, E2, and E3) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and stained with Ponceau S (lower panel). The presence of GST-14-3-3ζ was subsequently determined by Western blot using anti-14-3-3ζ antibody (upper panel). n = 3. B, GST-14-3-3ζ was subjected to thrombin digestion for 1, 2, and 18 h. Digests were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were stained with colloidal Coomassie Blue. C, MBP or MBP-RACK1 immobilized on amylose resin was incubated with recombinant thrombin-digested 14-3-3ζ. After extensive washing, proteins were eluted in loading buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and stained with Ponceau S (lower panel). The presence of 14-3-3ζ was subsequently determined by Western blot (upper panel). n = 2. D, recombinant MBP and MBP-RACK1 were immobilized on an amylose resin column and incubated with recombinant thrombin-digested 14-3-3θ. After extensive washing, proteins were eluted with loading buffer (MBP resin and MBP-RACK1 resin lanes) or with maltose (E1 and E2). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and stained with Ponceau S (lower panel). The presence of 14-3-3θ was subsequently determined by Western blot using an anti-pan14-3-3 antibody (upper panel). n = 2. E, SHSY5Y cells were lysed in IP buffer supplemented with MnCl2. Cell lysate was treated with λ-phosphatase (λ PPase) before the immunoprecipitation assay with anti-RACK1 antibody. The presence of 14-3-3ζ in the RACK1 immunoprecipitate was subsequently determined by Western blot. In parallel, the efficiency of protein dephosphorylation was controlled in the same samples by Western blot analyses using several anti-phosphospecific antibodies. Ponceau S staining was used to control for sample loading in SDS-PAGE. n = 4.

The majority of 14-3-3 family binding partners contain the consensus sequence RSXpSXP or RX(Y/F)XpSXP (where pS is phosphoserine), allowing a phosphoserine-dependent interaction (35–37). An alternative binding motif, (pS/pT)X1–2-COOH (where pT is phosphothreonine), implicating a serine or threonine at the carboxyl terminus of the 14-3-3 partners, was also proposed (41). These binding motifs are not found in the primary sequence of RACK1 (see Scansite), and as the E. coli-produced proteins bind each other, we hypothesized that RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ interact in a phosphorylation-independent manner. We tested this possibility by determining whether 14-3-3ζ co-immunoprecipitates with RACK1 from SHSY5Y lysate treated with λ-phosphatase. As shown Fig. 3E (middle panels), λ-phosphatase treatment of cell lysate led to the efficient dephosphorylation of well characterized phosphorylated residues of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (42), extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2), and ribosomal S6 (43) in the cell lysate. However, dephosphorylation failed to affect the co-immunoprecipitation of 14-3-3ζ with RACK1 (Fig. 3E, top panels). Together, these findings indicate that the association of 14-3-3ζ with RACK1 does not require a phosphorylated amino acid.

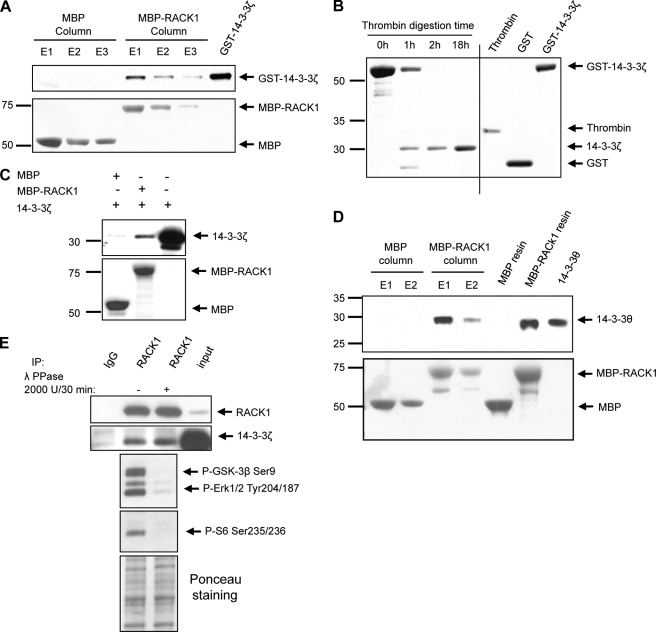

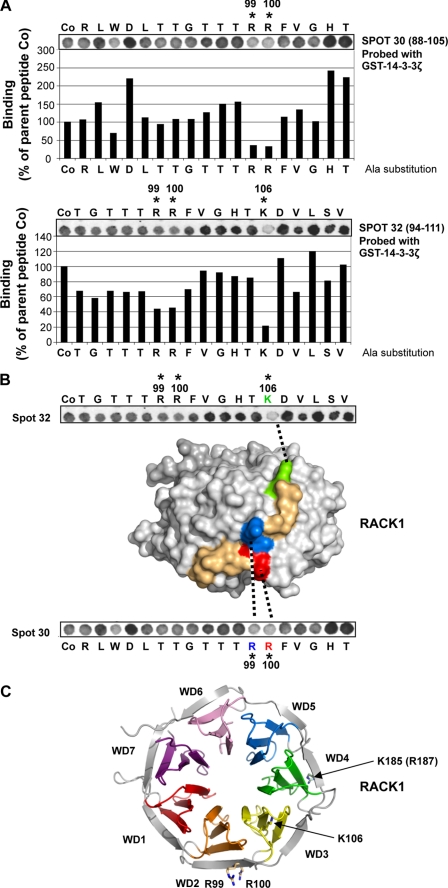

Mapping of 14-3-3ζ Binding Site on RACK1

To identify the binding site of 14-3-3ζ on RACK1, we took advantage of a RACK1 peptide array that we previously used to map the binding sites of PP2A, β1 integrin, and focal adhesion kinase on RACK1 (29, 30). Specifically, a library of overlapping peptides (18-mers), each shifted by three amino acids and encompassing the entire sequence of RACK1, was spot-synthesized on nitrocellulose membranes to generate RACK1 peptide arrays (supplemental Fig. S4). Bound peptides were then overlaid with recombinant GST or GST-14-3-3ζ, and binding of 14-3-3ζ to the RACK1-derived peptides was detected by anti-GST antibody. As reported previously (29), GST did not bind to any of the peptide spots on the RACK1 array (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. S4). However and in agreement with the results above showing a direct interaction between RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ, GST-14-3-3ζ bound to RACK1 peptides 28–33 and 58–60 (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. S4). Together, these data led to the identification of two candidate regions within the RACK1 sequence that contribute to a 14-3-3ζ binding interface, namely residues in the sequences 82–114 and 172–195 that span propeller blades WD2–3 and WD4–5, respectively (Fig. 4, B and C).

FIGURE 4.

Peptide array analysis of RACK1 for identification of potential 14-3-3ζ binding loci. A, an array of immobilized 18-mer peptide spots frame-shifted in three-residue increments and spanning the entire length of RACK1 was probed with GST-14-3-3ζ. Binding of 14-3-3ζ was detected (dark spots) using anti-GST antibody (presented here for peptides 26–36 and 55–65). n = 2. B, tabulated sequences for peptides spots 26–36 and 55–65 corresponding to the amino acid sequence of RACK1. RACK1-derived peptides interacting with 14-3-3ζ are shaded. C, the schematic of RACK1 structure defines the position of the WD repeats and highlights the relative locations of candidate loci for 14-3-3ζ binding; peptide numbers relate to the tabulated sequences detailed in B.

Next, to identify specific amino acids that are crucial for the interaction of RACK1 with 14-3-3ζ, we used peptide-scanning arrays derived from parent peptides 28, 30, 32, and 59 (Fig. 4B) in which successive amino acids were individually substituted by alanine. This alanine-scanning peptide array approach was previously used successfully to identify specific residues contributing to the RACK1 binding sites for PP2A and focal adhesion kinase (29, 30). Using the progeny array derived from peptides 28, 30, and 32, we found that individual alanine substitutions for Arg99, Arg100, and Lys106 significantly decreased the binding of GST-14-3-3ζ (Fig. 5A). Alanine substitution of a single residue, Lys185, within peptide 59 in the region spanning RACK1 blades WD4–5 also compromised binding to GST-14-3-3ζ (supplemental Fig. S5). These data suggest that amino acid residues that span the propeller blades WD2–3 and WD4–5 of RACK1 mediate the interaction with 14-3-3ζ, although a higher number of contacts are located within the WD2–3 region than the WD4–5 propeller blade (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 5.

Alanine-scanning array analysis of RACK1 peptides 30 and 32. A, arrays in which the 18 amino acids in RACK1-derived 18-mer peptides 30 and 32 (defined in Fig. 4B) were sequentially substituted with alanine were probed using GST-14-3-3ζ. The binding of GST-14-3-3ζ to each alanine-substituted RACK1 peptide was detected by anti-GST antibody and quantified by densitometry and is presented here as a percentage relative to the binding of GST-14-3-3ζ to the unsubstituted parent peptides (Co). n = 2. B, a surface rendition of the homologous A. thaliana RACK1A structure (9) with the cognate sequence (93AAGVSTRRFVGHTK106) shown colored reveals that the residues have prominent exposure on the edge of propeller blade WD2 and connecting loop to blade WD3. C, structure of RACK1A protein from A. thaliana (9) showing prominently surface-exposed side chains of basic residues Arg99, Arg100, and Lys106 (indicated by *) and cognate residue Lys185 (Arg187 in RACK1A) from the 14-3-3ζ binding locus on RACK1.

If amino acids Arg99, Arg100, Lys106, and Lys185 within the RACK1 sequence contribute to the direct interaction with 14-3-3ζ, they should be present on the outer surface of RACK1. As yet, the x-ray crystal structure for human RACK1 has not been solved. However, inspection of the structure of the highly homologous RACK1A protein from Arabidopsis thaliana (9) allowed us to assess the likelihood of surface exposure of the candidate 14-3-3ζ-interacting residues. We observed that the RACK1A sequence 93AAGVSTRRFVGHTK106 corresponding to RACK1 93TTGTTTRRFVGHTK106, which contains the conserved Arg99, Arg100, and Lys106 residues, is part of the outer edge of propeller blade WD2 and the loop of blade WD3, and all three amino acids are prominently exposed within this region (Fig. 5, B and C). In addition, we observed that the cognate residue Lys185 (Arg187 in RACK1A) is also exposed on the outer β-strand of the propeller blade WD4 (Fig. 5C). Together, these results strongly suggest that these amino acids are important for the interaction of the two scaffolding proteins.

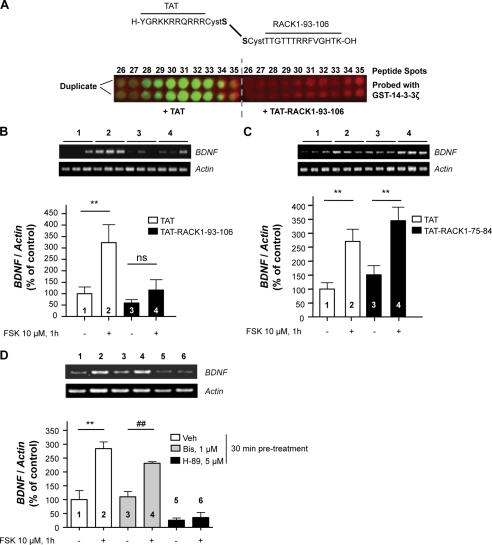

Disruption of Interaction between 14-3-3ζ and RACK1 Inhibits cAMP-mediated BDNF Transcription

Previously, we showed that the cAMP/PKA-mediated translocation of RACK1 to the nucleus results in the induction of BDNF transcription (12, 16). If the binding of 14-3-3ζ to RACK1 is necessary for this process, then the disruption of the direct interaction between of the two proteins should attenuate BDNF transcription. To test this possibility, the peptide 93TTGTTTRRFVGHTK106 identified above as a 14-3-3ζ binding site on RACK1 was synthesized. To allow for intracellular transduction, the RACK1 peptide was conjugated via a disulfide bond to the cell-penetrating peptide TAT (44) (Fig. 6A). First, we confirmed that TAT-RACK1-(93–106) efficiently blocked the direct interaction between GST-14-3-3ζ and spots 28–33 of the array (Fig. 6A). Next, SHSY5Y cells were pretreated with TAT-RACK1-(93–106) or the TAT peptide for 30 min prior to the activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway by FSK for 1 h, a time point after which increased BDNF mRNA levels can be detected (12). We observed that preincubation of SHSY5Y cells with the TAT-RACK1-(93–106) peptide, but not the TAT peptide, inhibited the induction of BDNF transcription in response to FSK (Fig. 6B). To test for the specificity of the effect of the TAT-RACK1-(93–106) peptide, SHSY5Y cells were also preincubated with TAT-RACK1-(75–84) (75GQFALSGSWD84), a peptide derived from a region of RACK1 that does not interact with 14-3-3ζ (see spots 23, 24, and 25 in supplemental Fig. S4). Importantly, unlike TAT-RACK1-(93–106), preincubation of SHSY5Y cells with TAT-RACK1-(75–84) peptide did not alter the induction of BDNF transcription in response to FSK (Fig. 6C). Together, these results suggest that the protein/protein interaction between RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ is essential for the induction of BDNF transcription.

FIGURE 6.

TAT-RACK1-(93–106) peptide blocks cAMP-mediated induction of BDNF transcription. A, RACK1-derived 18-mer peptides 26–35 were incubated with GST-14-3-3ζ in the presence of 100 μm TAT or TAT-RACK1-(93–106) peptide for 2 h at room temperature. Binding of 14-3-3ζ was detected (green spots) by anti-GST antibody and Alexa Fluor 800-coupled secondary antibody using a green channel of an Odyssey infrared image scanner. Peptide autofluorescence in the red channel was used to control the presence of immobilized 18-mer peptide spots 26–35 on both arrays. n = 2. B and C, SHSY5Y cells were incubated with 10 μm TAT, TAT-RACK1-(93–106) (B), or TAT-RACK1-(75–84) (C) peptide for 30 min prior to treatment with 10 μm FSK for 1 h. The levels of BDNF and actin mRNAs were analyzed by RT-PCR. The histogram depicts the mean ratio of BDNF to actin expressed as the percentage of control ±S.E. In B, n = 8–9. Two-way ANOVA showed a main effect of treatment (F(1,31) = 8.41, p = 0.007) and peptide (F(1,31) = 6.62, p = 0.015) but no interaction (F(1,31) = 2.99, p = 0.094). Subsequent analysis using the method of contrasts (one-tailed unpaired t test) detected a significant difference between vehicle and FSK in the TAT peptide group (**, p = 0.008) but not in the TAT-RACK1-(93–106) peptide group (ns, p = 0.114). In C, n = 5–6. Two-way ANOVA showed a main effect of treatment (F(1,19) = 23.68, p < 0.001) but no effect of the peptide (F(1,19) = 2.81, p = 0.11) or interaction (F(1,19) = 0.01, p = 0.756). Subsequent analysis using the method of contrasts (one-tailed unpaired t test) detected a significant difference between vehicle (Veh) and FSK in both TAT peptide group (**, p = 0.003) and TAT-RACK1-(75–84) peptide group (**, p = 0.004). D, SHSY5Y cells were incubated with 1 μm bisindolylmaleimide I hydrochloride (Bis) or 5 μm H-89 for 30 min before treatment with 10 μm FSK for 1 h. The levels of BDNF and actin mRNA were analyzed by RT-PCR. The histogram depicts the mean ratio of BDNF to actin expressed as the percentage of control ±S.E. n = 3; **, p = 0.005; ##, p = 0.002 (one-tailed unpaired t test). Numbers refer to the treatment indicated in the image and histogram.

The RACK1-derived peptide 99RRFVGHTKDV108 disrupts the interaction between PKCβII and RACK1 (45). Because RACK1 binds activated PKCβII (5, 14), we tested whether PKC activity is required for the cAMP/PKA-dependent transcription of BDNF. As shown in Fig. 6D, we observed that the PKA inhibitor H-89, but not the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I hydrochloride (46), blocked FSK-induced BDNF transcription. This finding indicates that PKC does not participate in cAMP/PKA-dependent BDNF transcription, and therefore a disruption of PKCβII and RACK1 interaction is unlikely to account for the inhibitory effect of TAT-RACK1-(93–106) peptide on cAMP/PKA-dependent transcription of BDNF.

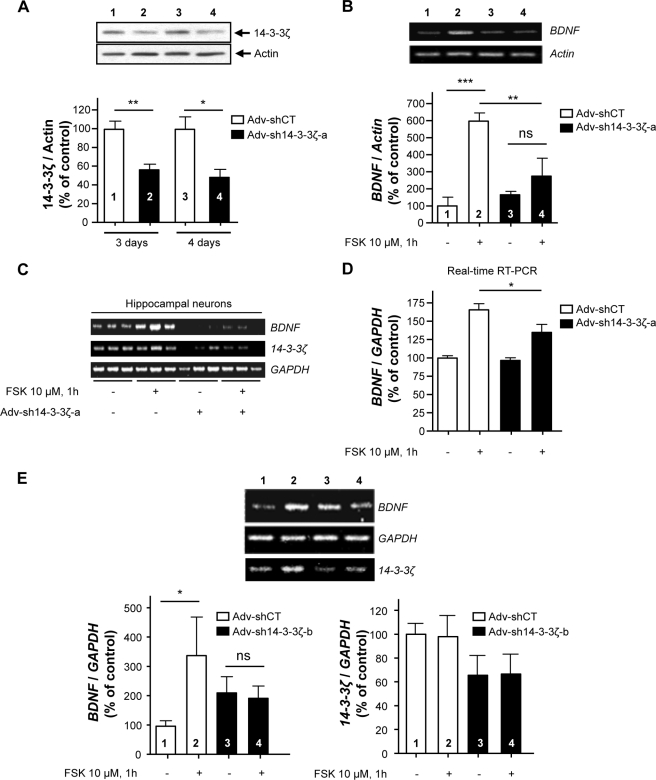

Next, to verify a specific role for 14-3-3ζ in the molecular mechanism underlying cAMP/PKA-induced BDNF transcription, the 14-3-3ζ gene was silenced, and the level of BDNF mRNA in the presence and absence of FSK was examined. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of a previously described shRNA 14-3-3ζ sequence (Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-a) (25), but not a virus expressing a nonspecific shRNA sequence (Adv-shCT), resulted in a significant knockdown of the 14-3-3ζ protein in SHSY5Y cells (Fig. 7A). Importantly, we observed that shRNA-mediated knockdown of 14-3-3ζ inhibited the induction of BDNF transcription in response to FSK treatment in SHSY5Y cells (Fig. 7B) and in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 7, C and D). Finally, to rule out the possibility of off-target effects, a second recombinant adenovirus expressing another sh14-3-3ζ RNA sequence (Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-b) was constructed. We observed that down-regulation of 14-3-3ζ using Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-b also inhibited BDNF transcription following FSK treatment in SHSY5Y cells (Fig. 7E). Together, the data described above suggest that the association of 14-3-3ζ to RACK1 is necessary for the transcriptional regulation of BDNF expression in response to activation of cAMP/PKA signaling.

FIGURE 7.

Down-regulation of 14-3-3ζ expression inhibits cAMP-induced BDNF transcription. A, control (Adv-shCT) and Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-a recombinant adenoviruses were used to infect SHSY5Y cells for 3 and 4 days. The 14-3-3ζ protein level was analyzed by Western blot. The histogram depicts the mean ratio of 14-3-3ζ to actin expressed as the percentage of control ±S.E. n = 3; **, p = 0.007; *, p = 0.016 (one-tailed unpaired t test). B, SHSY5Y cells were infected with recombinant Adv-shCT or Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-a for 3 days and treated with 10 μm FSK for 1 h. The levels of BDNF and actin mRNAs were analyzed by RT-PCR. The histogram depicts the mean ratio of BDNF to actin expressed as the percentage of control ±S.E. n = 3. Two-way ANOVA showed an interaction between the treatment and the virus (F(1,8) = 9.16, p = 0.016). ***, p < 0.001; **, p = 0.007; ns, p = 0.26 (Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis). C and D, down-regulation of 14-3-3ζ inhibits cAMP/PKA-mediated induction of BDNF transcription in hippocampal neurons. After 14 days in culture, rat hippocampal neurons were infected with recombinant Adv-shCT or Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-a. Seven days later, neurons were treated with vehicle or 10 μm FSK (1 h). C, the levels of BDNF, 14-3-3ζ, and GAPDH mRNAs were analyzed by RT-PCR. n = 3. D, the levels of BDNF and GAPDH mRNAs were analyzed by TaqMan RT-PCR. The histogram depicts the mean ratio of BDNF to GAPDH expressed as the percentage of control ±S.E. n = 5–6. Two-way ANOVA showed an effect of both treatment (F(1,19) = 51.12, p < 0.001) and virus (F(1,19) = 5.51, p = 0.03) but no interaction (F(1,19) = 3.57, p = 0.074). Subsequent analysis using the method of contrasts (one-tailed unpaired t test) detected a significant difference between Adv-shCT and Adv-sh14-3-3ζ within the FSK-treated group (*, p = 0.030). E, SHSY5Y cells were infected with recombinant Adv-shCT or Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-b for 3 days and treated with 10 μm FSK for 1 h. The levels of BDNF, 14-3-3ζ, and GAPDH mRNAs were analyzed by RT-PCR. The histograms depict the mean ratio of BDNF or 14-3-3ζ to GAPDH expressed as the percentage of control ±S.E. n = 5–6. Two-way ANOVA detected no interaction (F(1,19) = 3.67, p = 0.070). Subsequent analysis using the method of contrasts (one-tailed unpaired t test) detected a significant difference between vehicle (−) and FSK (+) within the Adv-shCT group (*, p = 0.038) but not within the Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-b group (ns). A two-way ANOVA was used to analyze 14-3-3ζ knockdown and showed no effect of the treatment (F(1,16) = 0.001, p = 0.975) but did show an effect of the virus (F(1,16) = 4.58, p = 0.048). n = 4–6. Numbers refer to the treatment indicated in the image and histogram.

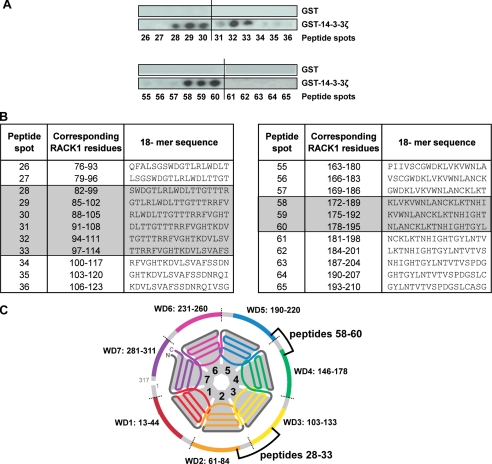

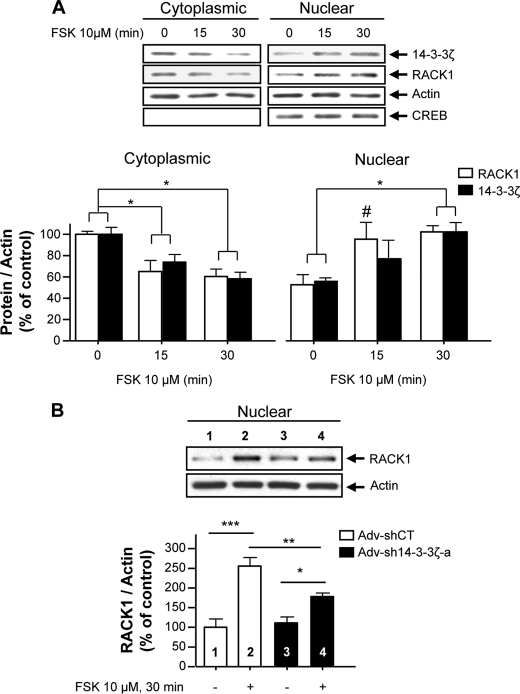

14-3-3ζ Is Necessary for cAMP-mediated Translocation of RACK1 into Nucleus

Given the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling property of 14-3-3ζ (39), we hypothesized that 14-3-3ζ is required for the nuclear translocation of RACK1, a prerequisite for the activation of BDNF transcription upon activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway (12, 16). To test this possibility, we first examined the subcellular localization of both 14-3-3ζ and RACK1 following FSK treatment in SHSY5Y cells. As reported previously (16, 47, 48), we observed that the activation of the cAMP/PKA-mediated signaling pathway resulted in RACK1 translocation from the cytosolic fraction to the nucleus (Fig. 8A). Importantly, we found that 14-3-3ζ was also translocated to the nucleus in response to FSK treatment and that the time course of the movement of both scaffolding proteins was similar (Fig. 8A).

FIGURE 8.

14-3-3ζ is necessary for cAMP-mediated nuclear translocation of RACK1. A, SHSY5Y cells were treated with 10 μm FSK for 15 and 30 min. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared, and an equal amount of proteins was resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The levels of 14-3-3ζ, RACK1, actin, and CREB in each fraction were analyzed by Western blot analysis. The histogram depicts the mean ratio ±S.E. of 14-3-3ζ or RACK1 to actin and is expressed as the percentage of control. n = 3–4. One-way ANOVA showed significant effects of time for cytoplasmic 14-3-3ζ (F(2,8) = 9.24, p = 0.008), for cytoplasmic RACK1 (F(2,6) = 8.47, p = 0.018), for nuclear 14-3-3ζ (F(2,9) = 4.05, p = 0.055), and for nuclear RACK1 (F(2,8) = 7.44, p = 0.015). *, p < 0.05; #, p < 0.05 (15 versus 0 min) (Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis). B, down-regulation of the 14-3-3ζ gene inhibits cAMP/PKA-mediated RACK1 translocation to the nucleus. SHSY5Y cells were infected with recombinant Adv-sh14-3-3ζ-a or Adv-shCT for 3 days as described in Fig. 7A and treated with 10 μm FSK for 30 min, and the levels of RACK1 and actin in each fraction were analyzed by Western blot analysis. The histogram depicts the mean ratio ±S.E. of RACK1 to actin and is expressed as the percentage of control. n = 4. Two-way ANOVA showed an interaction between the treatment and the virus (F(1,12) = 6.37, p = 0.027). ***, p < 0.001; **, p = 0.009; *, p = 0.019 (Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis). Numbers refer to the treatment indicated in the image and histogram.

Finally, we examined whether 14-3-3ζ was necessary for RACK1 nuclear translocation upon activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway. To do so, we determined the fate of RACK1 localization after silencing the 14-3-3ζ gene. As shown in Fig. 8B, shRNA-mediated knock-down of 14-3-3ζ attenuated cAMP/PKA-induced RACK1 translocation to the nucleus. Taken together, our results suggest that 14-3-3ζ mediates BDNF transcription by promoting RACK1 translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus upon cAMP/PKA pathway activation.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we set out to identify the mechanism of RACK1 nuclear translocation in response to the activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway, a key step leading to BDNF transcription (12, 16). Using a proteomics strategy, we identified the scaffolding protein 14-3-3ζ as a binding partner of RACK1. We found that the interaction between the two scaffolding proteins was direct but did not require the prior phosphorylation of RACK1 on consensus 14-3-3ζ binding sites. Importantly, we provide evidence to suggest that 14-3-3ζ is necessary for the shuttling of RACK1 to the nucleus and the subsequent activation of BDNF transcription.

14-3-3θ was also identified by mass spectrometry as a potential RACK1 binding partner, and we found that the isoform directly interacted with RACK1 in vitro. This finding is in agreement with the fact that 14-3-3 isoforms share direct binding partners. It is also well recognized that 14-3-3 proteins function as homo- and heterodimers (35–37). Therefore, our data put forward the possibility that RACK1 can interact with a 14-3-3ζ/14-3-3θ heteromer.

Using a RACK1-derived peptide array approach, we identified two putative binding sites for 14-3-3ζ, 93TTGTTTRRFVGHTK106 and 178NLANCKLKTNHI189, located on the WD2–3 and WD4–5 propeller blades, respectively, of RACK1. The fact that we identified two binding regions for 14-3-3ζ on the RACK1 sequence is not surprising because both proteins have been shown to make multiple contacts with their various binding partners (6, 35–37). However, the alanine-scanning array used to identify amino acids within the RACK1 sequence that mediate the interaction between RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ implicated a cluster of three residues (i.e. Arg99, Arg100, and Lys106), suggesting that the 93TTGTTTRRFVGHTK106 region is likely to be the high affinity 14-3-3ζ binding site for RACK1. Importantly, the x-ray structure of RACK1A protein from A. thaliana that shares 66% identity with human RACK1 (9) showed that the 93TTGTTTRRFVGHTK106 sequence of RACK1 is exposed to the surface. Furthermore, this region has been reported previously to mediate other RACK1 interactions such as with PKCβII whose interaction with RACK1 is inhibited by 99RRFVGHTKDV108 peptide (45). The fact that PKCβII and 14-3-3ζ share a binding region on RACK1 is of particular interest because multiple 14-3-3 isoforms, including 14-3-3ζ, are also known to directly interact with several PKC isoforms (49–52). However, whereas RACK1 binds activated PKC (5, 14), 14-3-3 binding to PKC inhibits its activity (36, 50–52). Therefore, it is plausible that a competition between PKC and 14-3-3 for RACK1 binding might also regulate PKC signaling.

Strikingly, although 14-3-3 proteins typically bind their partners through phosphorylated motifs (35–37), our data provide evidence that this is not the case for the interaction with RACK1. First, the amino acid sequence of RACK1 does not contain the 14-3-3 phosphobinding motifs, and the RACK1 amino acids we identified to be crucial for the interaction of the two proteins are basic residues. Furthermore, E. coli-expressed non-phosphorylated 14-3-3ζ and RACK1 proteins interact with each other in vitro. In line with these findings, we also observed that 14-3-3ζ bound to non-phosphorylated RACK1-derived peptides using an in vitro overlay assay. Finally, dephosphorylation of cellular proteins with the general phosphatase λ-phosphatase did not alter the association of 14-3-3ζ with RACK1. Therefore, we propose that RACK1, like proteins such as the human telomerase (53), the amyloid β-protein precursor intracellular domain fragment (54), and the potassium channel Kir6.2 (55), does not require a phosphorylated amino acid to directly bind 14-3-3ζ.

RACK1 is known to regulate signaling cascades by means of both constitutive (e.g. phosphodiesterase PDE4D5 and focal adhesion kinase) and signal-dependent protein association (e.g. PKC) and dissociation (e.g. Fyn) (6). Likewise, 14-3-3 proteins have been reported to have both constitutive (e.g. Raf-1) and signal-dependent (e.g. histone deacetylase (56)) binding partners. Our data indicate that RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ interaction is constitutive as it could be detected in resting cells. This raises the possibility that these two multifunctional scaffolding proteins take part in a preassembled signaling framework that may integrate and disseminate cellular signaling events (2). In agreement with this possibility, both RACK1 (22, 57) and 14-3-3 proteins (36) are able to form dimers and to simultaneously bind several proteins (6), providing a way to tether multiple signaling molecules in close proximity to each other. Furthermore, we observed that the association between RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ was not dramatically affected in response to activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway by FSK. However, it is noteworthy that cAMP/PKA signaling is highly spatially compartmentalized (58, 59). Therefore, a localized increased concentration in cellular cAMP/PKA is expected to affect only a small fraction of the total signaling proteins, making it difficult to detect any modification in the level of the constitutive interaction between the two highly expressed proteins RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ.

We showed that RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ were both translocated to the nucleus following activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway and that 14-3-3ζ gene silencing attenuated RACK1 nuclear compartmentalization. In agreement with these findings, the 14-3-3 family of proteins has been reported to display nucleocytoplasmic shuttling properties (38, 39). This occurs primarily by the interaction of 14-3-3 proteins on their binding partner at or in close proximity to a nuclear localization signal or a nuclear export signal, which consequently hinders their function (60). In addition, signal-dependent nuclear translocation of 14-3-3 proteins has been described upon treatment of different types of cells with calcium (61) or tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (62). Interestingly, in lung epithelial cells, 14-3-3ζ acts as an escort in the calcium-dependent nuclear import of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α, which in turn regulates phosphatidylcholine lipid synthesis (61). As RACK1 does not display in its sequence a known nuclear localization signal, our data provide evidence to suggest that the cAMP/PKA-mediated nuclear shuttling of RACK1 is assisted by its interaction with 14-3-3ζ. Furthermore, RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ are preassembled in a complex prior to the activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway. For these reasons, it is also plausible that the binding of a third component to the complex is controlled directly or indirectly by PKA and that the phosphorylated protein drives the translocation of the RACK1/14-3-3ζ assembly. One intriguing possibility of such binding partner is the actin regulatory protein cofilin. We identified cofilin as another RACK1 binding partner in the same screen in which 14-3-3ζ was identified,5 and interestingly, phosphocofilin was shown previously to interact with 14-3-3ζ (63). Cofilin is phosphorylated by LIM kinase (64), and PKA phosphorylation is required for LIM kinase activity and thus for cofilin phosphorylation (65). This possibility will be explored in future studies.

Once it entered into the nucleus in response to the activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway, RACK1 localized at the BDNF promoter IV region where it regulates chromatin modification, ultimately leading to BDNF transcription (12). Interestingly, Aguilera et al. (62) reported previously that upon treatment of HEK cells with TNFα, 14-3-3 proteins translocate to the nucleus and associate with several TNFα-responsive promoters to control gene transcription. These findings are in agreement with the fact that 14-3-3 proteins can interact with histones (66–68) and mediate transcriptional activation (69, 70). Therefore, a potential model would predict that after cAMP/PKA-mediated translocation into the nucleus, 14-3-3ζ participates in chromatin modifications at the level of BDNF promoter IV by recruiting chromatin and/or histone remodeler complexes (70, 71).

RACK1 and 14-3-3 proteins are two multifunctional proteins that participate in a wide range of signaling events in different tissues. Therefore, besides cAMP/PKA-induced BDNF transcription, it is likely that RACK1/14-3-3 interaction also regulates other relevant cellular processes. In agreement with this possibility, RACK1 and 14-3-3σ (also named stratifin) were reported to mediate proteasomal degradation of the oncogenic ΔNp63α protein upon DNA damage induced by cisplatin (72). Therefore, it is possible that this functional cooperation relies at least in part on RACK1/14-3-3σ interaction.

In summary, our data show that RACK1 and 14-3-3ζ are binding partners and that their direct association results in cAMP/PKA-mediated RACK1 translocation and BDNF expression. These results are likely to have implications in cellular functions that are regulated via the cAMP/PKA pathway as well as in neuronal functions that are controlled by BDNF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yun-Cai Liu (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology) for providing the GST-14-3-3ζ and GST-14-3-3θ constructs. The University of California, San Francisco Sandler-Moore Mass Spectrometry Core Facility acknowledges support from the Sandler Family Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and National Institutes of Health/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA082103. PyMOL from W. L. DeLano, DeLano Scientific, was used to create the protein structure images in this work.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AA016848 from the NIAAA (to D. R.). This work was also supported by Cancer Research Ireland and the Health Research Board of Ireland (to P. A. K. and R. O.), Science Foundation Ireland (to R. O.), and the State of California for medical research on alcohol and substance Abuse through the University of California, San Francisco (to D. R.).

This article contains supplemental Methods and Figs. S1–S5.

J. Neasta and D. Ron, unpublished data.

- BDNF

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- Adv

- adenovirus

- CREB

- cAMP/PKA response element-binding protein

- CT

- control

- FSK

- forskolin

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- Bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- FAK

- Fokal Adhesion Kinase

- CCTα

- CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pawson T., Scott J. D. (1997) Science 278, 2075–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scott J. D., Pawson T. (2009) Science 326, 1220–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shaw A. S., Filbert E. L. (2009) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kholodenko B. N., Hancock J. F., Kolch W. (2010) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 414–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ron D., Chen C. H., Caldwell J., Jamieson L., Orr E., Mochly-Rosen D. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 839–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adams D. R., Ron D., Kiely P. A. (2011) Cell Commun. Signal. 9, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stirnimann C. U., Petsalaki E., Russell R. B., Müller C. W. (2010) Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 565–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nilsson J., Sengupta J., Frank J., Nissen P. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5, 1137–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ullah H., Scappini E. L., Moon A. F., Williams L. V., Armstrong D. L., Pedersen L. C. (2008) Protein Sci. 17, 1771–1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McCahill A., Warwicker J., Bolger G. B., Houslay M. D., Yarwood S. J. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 62, 1261–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qiu Y., Mao T., Zhang Y., Shao M., You J., Ding Q., Chen Y., Wu D., Xie D., Lin X., Gao X., Kaufman R. J., Li W., Liu Y. (2010) Sci. Signal. 3, ra7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He D. Y., Neasta J., Ron D. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19043–19050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robles M. S., Boyault C., Knutti D., Padmanabhan K., Weitz C. J. (2010) Science 327, 463–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ron D., Jiang Z., Yao L., Vagts A., Diamond I., Gordon A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 27039–27046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arimoto K., Fukuda H., Imajoh-Ohmi S., Saito H., Takekawa M. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1324–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yaka R., He D. Y., Phamluong K., Ron D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9630–9638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hong E. J., McCord A. E., Greenberg M. E. (2008) Neuron 60, 610–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Poo M. M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang H., Storm D. R. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 463–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xia Z., Storm D. R. (2005) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ron D., Luo J., Mochly-Rosen D. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 24180–24187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thornton C., Tang K. C., Phamluong K., Luong K., Vagts A., Nikanjam D., Yaka R., Ron D. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 31357–31364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moulédous L., Neasta J., Uttenweiler-Joseph S., Stella A., Matondo M., Corbani M., Monsarrat B., Meunier J. C. (2005) Mol. Pharmacol. 68, 467–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeanblanc J., He D. Y., Carnicella S., Kharazia V., Janak P. H., Ron D. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 13494–13502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Z., Zhao J., Du Y., Park H. R., Sun S. Y., Bernal-Mizrachi L., Aitken A., Khuri F. R., Fu H. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 162–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ptasznik A., Nakata Y., Kalota A., Emerson S. G., Gewirtz A. M. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, 1187–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frank R. (2002) J. Immunol. Methods 267, 13–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Frank R., Overwin H. (1996) Methods Mol. Biol. 66, 149–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kiely P. A., Baillie G. S., Barrett R., Buckley D. A., Adams D. R., Houslay M. D., O'Connor R. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20263–20274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kiely P. A., Baillie G. S., Lynch M. J., Houslay M. D., O'Connor R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22952–22961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gangisetty O., Reddy D. S. (2009) J. Neurosci. Methods 181, 58–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fogal V., Gostissa M., Sandy P., Zacchi P., Sternsdorf T., Jensen K., Pandolfi P. P., Will H., Schneider C., Del Sal G. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 6185–6195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McGough N. N., He D. Y., Logrip M. L., Jeanblanc J., Phamluong K., Luong K., Kharazia V., Janak P. H., Ron D. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 10542–10552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mackintosh J. A., Choi H. Y., Bae S. H., Veal D. A., Bell P. J., Ferrari B. C., Van Dyk D. D., Verrills N. M., Paik Y. K., Karuso P. (2003) Proteomics 3, 2273–2288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dougherty M. K., Morrison D. K. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 1875–1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bridges D., Moorhead G. B. (2005) Sci. STKE 2005, re10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morrison D. K. (2009) Trends Cell Biol. 19, 16–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brunet A., Kanai F., Stehn J., Xu J., Sarbassova D., Frangioni J. V., Dalal S. N., DeCaprio J. A., Greenberg M. E., Yaffe M. B. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 156, 817–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van Hemert M. J., Niemantsverdriet M., Schmidt T., Backendorf C., Spaink H. P. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 1411–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Watanabe M., Isobe T., Ichimura T., Kuwano R., Takahashi Y., Kondo H., Inoue Y. (1994) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 25, 113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ganguly S., Weller J. L., Ho A., Chemineau P., Malpaux B., Klein D. C. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1222–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beaulieu J. M., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G. (2009) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 49, 327–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ruvinsky I., Meyuhas O. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 342–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gump J. M., Dowdy S. F. (2007) Trends Mol. Med. 13, 443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grosso S., Volta V., Sala L. A., Vietri M., Marchisio P. C., Ron D., Biffo S. (2008) Biochem. J. 415, 77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Davies S. P., Reddy H., Caivano M., Cohen P. (2000) Biochem. J. 351, 95–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. He D. Y., Vagts A. J., Yaka R., Ron D. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 62, 272–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ron D., Vagts A. J., Dohrman D. P., Yaka R., Jiang Z., Yao L., Crabbe J., Grisel J. E., Diamond I. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 2303–2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jones D. H., Martin H., Madrazo J., Robinson K. A., Nielsen P., Roseboom P. H., Patel Y., Howell S. A., Aitken A. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 245, 375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Robinson K., Jones D., Patel Y., Martin H., Madrazo J., Martin S., Howell S., Elmore M., Finnen M. J., Aitken A. (1994) Biochem. J. 299, 853–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Toker A., Sellers L. A., Amess B., Patel Y., Harris A., Aitken A. (1992) Eur. J. Biochem. 206, 453–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Meller N., Liu Y. C., Collins T. L., Bonnefoy-Bérard N., Baier G., Isakov N., Altman A. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 5782–5791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Seimiya H., Sawada H., Muramatsu Y., Shimizu M., Ohko K., Yamane K., Tsuruo T. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 2652–2661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sumioka A., Nagaishi S., Yoshida T., Lin A., Miura M., Suzuki T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42364–42374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yuan H., Michelsen K., Schwappach B. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 638–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. McKinsey T. A., Zhang C. L., Olson E. N. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 14400–14405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu Y. V., Hubbi M. E., Pan F., McDonald K. R., Mansharamani M., Cole R. N., Liu J. O., Semenza G. L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37064–37073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Willoughby D., Cooper D. M. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87, 965–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wong W., Scott J. D. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 959–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Muslin A. J., Xing H. (2000) Cell. Signal. 12, 703–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Agassandian M., Chen B. B., Schuster C. C., Houtman J. C., Mallampalli R. K. (2010) FASEB J. 24, 1271–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Aguilera C., Fernández-Majada V., Inglés-Esteve J., Rodilla V., Bigas A., Espinosa L. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 3695–3704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gohla A., Bokoch G. M. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 1704–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Huang T. Y., DerMardirossian C., Bokoch G. M. (2006) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nadella K. S., Saji M., Jacob N. K., Pavel E., Ringel M. D., Kirschner L. S. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 599–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Chen F., Wagner P. D. (1994) FEBS Lett. 347, 128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Taverna S. D., Li H., Ruthenburg A. J., Allis C. D., Patel D. J. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 1025–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Macdonald N., Welburn J. P., Noble M. E., Nguyen A., Yaffe M. B., Clynes D., Moggs J. G., Orphanides G., Thomson S., Edmunds J. W., Clayton A. L., Endicott J. A., Mahadevan L. C. (2005) Mol. Cell 20, 199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Winter S., Simboeck E., Fischle W., Zupkovitz G., Dohnal I., Mechtler K., Ammerer G., Seiser C. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 88–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zippo A., Serafini R., Rocchigiani M., Pennacchini S., Krepelova A., Oliviero S. (2009) Cell 138, 1122–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Drobic B., Pérez-Cadahía B., Yu J., Kung S. K., Davie J. R. (2010) Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 3196–3208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Fomenkov A., Zangen R., Huang Y. P., Osada M., Guo Z., Fomenkov T., Trink B., Sidransky D., Ratovitski E. A. (2004) Cell Cycle 3, 1285–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.