Background: The mammalian glycosyltransferases LFNG and MFNG transfer GlcNAc to O-fucose on NOTCH and regulate NOTCH signaling.

Results: If galactose is added to the GlcNAc transferred by LFNG, Delta1/NOTCH signaling is enhanced, but galactose inhibits NOTCH signaling stimulated by MFNG.

Conclusion: LFNG and MFNG Fringe modulate NOTCH differently.

Significance: Galactose on O-fucose glycans modulates Delta1/NOTCH signaling.

Keywords: Carbohydrate Function, Cell Surface, Glycosyltransferases, Membrane Proteins, Signal Transduction, Delta1, Fringe, Galactose, Jagged1, NOTCH

Abstract

NOTCH signaling induced by Delta1 (DLL1) and Jagged1 (JAG1) NOTCH ligands is modulated by the β3N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase Fringe. LFNG (Lunatic Fringe) and MFNG (Manic Fringe) transfer N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to O-fucose attached to EGF-like repeats of NOTCH receptors. In co-culture NOTCH signaling assays, LFNG generally enhances DLL1-induced, but inhibits JAG1-induced, NOTCH signaling. In mutant Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that do not add galactose (Gal) to the GlcNAc transferred by Fringe, JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling is not inhibited by LFNG or MFNG. In mouse embryos lacking B4galt1, NOTCH signaling is subtly reduced during somitogenesis. Here we show that DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling in CHO cells was enhanced by LFNG, but this did not occur in either Lec8 or Lec20 CHO mutants lacking Gal on O-fucose glycans. Lec20 mutants corrected with a B4galt1 cDNA became responsive to LFNG. By contrast, MFNG promoted DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling better in the absence of Gal than in its presence. This effect was reversed in Lec8 cells corrected by expression of a UDP-Gal transporter cDNA. The MFNG effect was abolished by a DDD to DDA mutation that inactivates MFNG GlcNAc transferase activity. The binding of soluble NOTCH ligands and NOTCH1/EGF1–36 generally reflected changes in NOTCH signaling caused by LFNG and MFNG. Therefore, the presence of Gal on O-fucose glycans differentially affects DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling modulated by LFNG versus MFNG. Gal enhances the effect of LFNG but inhibits the effect of MFNG on DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling, with functional consequences for regulating the strength of NOTCH signaling.

Introduction

NOTCH signaling plays highly conserved roles in determining cell fate and controlling cell growth in mammals and lower organisms (1). NOTCH proteins are transmembrane receptors containing multiple functional domains. In mammals, there are four NOTCH receptors with 29–36 epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) repeats in their extracellular domain (ECD).4 NOTCH receptors are stimulated by the canonical NOTCH ligands Delta1 (DLL1), Delta4 (DLL4), Jagged1 (JAG1), and Jagged2 (JAG2) to transduce a signal that alters the expression of many target genes (2). Hypomorphic NOTCH mutations result in developmental defects, and mutations in NOTCH also lead to cancer (3–5). Thus, identifying factors that modulate NOTCH signaling provide insight into mechanisms of development and tumorigenesis.

A key modulator of NOTCH signaling is Fringe (FNG) (6). Fringe was originally identified in Drosophila as essential for the precise positioning of NOTCH signaling at the dorsal/ventral boundary of the wing imaginal disc (7, 8). Mammals have three Fringe genes, Lfng, Mfng, and Rfng encoding Lunatic, Manic, and Radical Fringe, respectively (9, 10). All Fringe proteins have β1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase activity (11–13). Fringe enzymes transfer GlcNAc to O-linked fucose on EGF repeats that contain the consensus sequence C2X4–5S/TC3 (14, 15). Importantly, the addition of this GlcNAc to NOTCH has profound consequences for NOTCH signaling. Drosophila FNG confines NOTCH signaling to the wing border by inhibiting Serrate-induced NOTCH signaling and potentiating Delta-induced NOTCH signaling (7, 16). LFNG is the most similar mammalian homologue and is required for somitogenesis (17, 18), for optimal T cell development (19, 20), and for optimal production of MZB cells (21). In 3T3 cells expressing transfected NOTCH1, LFNG potentiates DLL1-induced signaling and inhibits JAG1-induced signaling (22, 23). In Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, LFNG and MFNG inhibit JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling (11, 24, 25).

Our previous studies showed that MFNG and LFNG are necessary but not sufficient to inhibit JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling in CHO cells in a co-culture NOTCH reporter assay (24). Using Lec8 and Lec20 CHO glycosylation mutants that do not add Gal to O-fucose glycans (24), we showed that inhibition of JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling by LFNG or MFNG requires the presence of Gal on O-fucose glycans (24). In mouse embryos lacking B4GALT1, we observed reduced expression of a set of NOTCH pathway genes during somitogenesis, and an average increase in the number of lumbar vertebrae in B4galt1 null embryos (26).

In this article we reveal roles for Gal in LFNG and MFNG modulation of DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling in CHO cells. Unexpectedly, we found a difference between LFNG and MFNG. Gal was required for the enhancement of NOTCH signaling by LFNG, whereas Gal inhibited the enhancement of DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling by MFNG. These findings may reflect differential modification of EGF repeats on NOTCH by LFNG versus MFNG as previously proposed (15, 25). LFNG and MFNG are both required for the optimal generation of MZB cells in spleen (21) consistent with a synergistic action on NOTCH. Our results show that the addition of Gal to O-fucose glycans differentially affects DLL1/NOTCH interactions depending on whether NOTCH EGF repeats are modified by LFNG or MFNG.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells

Pro−5 parent CHO and Lec1.3C, Lec2.6A, Lec8.3D, and Lec20.15C CHO glycosylation mutants derived from Pro−5 CHO cells, stably expressing control plasmid pMirb or pMirb/Lfng-AP (mouse) or pMirb/Mfng-AP (mouse) were generated and characterized previously (24). The cells are referred to in the text as Lec1, Lec2, Lec8, and Lec20, respectively. The different cloned lines used in this work are listed in Table 1. We previously showed that the O-fucose glycans expressed on NOTCH EGF repeats by these CHO cells reflect the predicted glycosylation status (24). CHO cells were cultured with α-MEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 400 μg/ml of G418 (GEMINI Bio-Products) at 37 °C. Independent Lec8 mutants stably expressing the inactive mutant MFNG/DDA were generated by transfection of the pMirb/Mfng/DDA plasmid and selection in G418. Fringe proteins fused to alkaline phosphatase (AP) are active in vitro and in vivo (9, 11, 24 and see below). Independent transfectants expressing similar AP activity in lysates and secretions were used in experiments (Table 1). Secreted Fringe activity was assayed as described below. L cells, and L cells stably expressing DLL1 (DLL1/L) or JAG1 (JAG1/L), were originally provided by Gerry Weinmaster (22, 23). These cells were periodically sorted by flow cytometry using anti-DLL1 and anti-JAG1 antibodies to obtain populations of high ligand expressors, and to obtain control L cells expressing no detectable ligand, as described (24, 27). L cells were cultured in α-MEM containing 10% FCS and antibiotics at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator.

TABLE 1.

Alkaline phosphatase activity of stable cell lines

The unit of AP activity is OD450/100 μl of medium when 3 × 105 cells were cultured in 2 ml of serum-free medium for 2 days. Symbols represent O-fucose glycans on NOTCH: triangle, fucose; black square, GlcNAc; gray circle, Gal; diamond, sialic acid.

Plasmids

The constructs pMirb/Mfng-AP and pMirb/Lfng-AP were previously described (11, 24) and the NOTCH reporter TP1-luciferase (28) and TK-Renilla luciferase (Promega) plasmids were also previously described (27). The B4galt1 cDNA (pSVL/SGT) was a gift from Joel and Nancy Shaper (29) and a cDNA containing a CHO UDP-Gal transporter (Slc35a2) was a gift from Rita Gerardy-Schahn (30).

Site-directed Mutagenesis

The MFNG/DDA mutation was made directly on pMirb/Mfng-AP (9) by changing the codon for Asp144 of mouse pMirB/Mfng-AP from GAC to GCC using primers 5′-GGTTCTGCCACGTGGATGATGCCAACTATGTGAACCC-3′ and 5′-GGGTTCACATAGTTGGCATCATCCACGTGGCAGAACC-3′ and a mutagenesis kit (QuikChange II XL, Stratagene). The mutated cDNA was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Alkaline Phosphatase Assay

CHO cells (3 × 105/well) expressing chimeric Fng-AP were cultured on 6-well plates with 2 ml of α-MEM at 37 °C for 2 days. Conditioned medium was centrifuged at 150 × g for 3 min to remove cells. Cell lysates were prepared in 250 μl of Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) after washing cells with 2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mm CaCl2, MnCl2, and MgCl2, pH 7.2 (PBS). Lysates were incubated at room temperature (RT) for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 150 × g for 3 min at RT to remove nuclei and centrifugation of the supernatant at 12,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. Conditioned medium or cell lysates were incubated at 65 °C for 15 min. AP activity was measured in 100 μl of test sample mixed with 100 μl of 1 mg/ml of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma) dissolved in 1 m diethanolamine buffer, pH 9.8, containing 0.5 mm MgCl2. The reaction was performed at 37 °C for 30 min in a 96-well plate. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader with Magellan 6 software (TECAN).

Fringe Activity Assay

Fringe glycosyltransferse activity was assayed following affinity purification of secreted FNG-AP on anti-AP beads essentially as described (31). CHO cells (4 × 105/well) were plated on a 6-well plate. The next day, cells were washed with 1 ml of PBS lacking calcium and magnesium (PBS/CMF) and cultured in 1.5 ml of serum-free medium, CHO-S-SFM II (Invitrogen), for 3 days. The medium was harvested and centrifuged at 830 × g at RT for 3 min and the supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant (1.3 ml) was incubated with Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 (20 mm), NaCl (150 mm), and 30 μl of bed volume of monoclonal anti-human placental alkaline phosphatase (clone 8B6)-agarose (Sigma) at 4 °C for 2 h with rotation. The agarose beads were washed with 0.5 ml of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, buffer containing 150 mm NaCl and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 three times, and then twice with 50 mm HEPES buffer, pH 6.8, containing 10 mm MnCl2. The agarose beads were incubated with 50 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, containing 10 mm MnCl2, 0.1 mg/ml of BSA, 50 mm p-nitrophenyl phosphate-fucose, 400 μm UDP-GlcNAc, and 0.5 μCi of UDP-[6-3H]GlcNAc (ARC) and 3.5 units of alkaline phosphatase (Roche Diagnostics) at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by adding 900 μl of 30 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, and loaded directly onto a C18 cartridge (Agilent) as described (13). The product was eluted from the C18 cartridge with 500 μl of 50% (v/v) methanol three times. The 3H activity in 500 μl of the eluted sample was measured using a liquid scintillation analyzer TRI-CARB 2100TR (Packard).

NOTCH Co-culture Signaling Assay

The co-culture NOTCH signaling assay was performed as described (24, 27) with slight modifications. CHO cells in a 12-well plate (4 × 104 cells per well) were cultured overnight before cotransfection with 80 ng of TP1-luciferase plasmid, 40 ng of pRL-TK Renilla luciferase plasmid, and 1 μg of plasmid DNA using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 16 h at 37 °C, 5 × 105 DLL1/L, JAG1/L, or untransfected L cells were overlaid. After another 32 h, cell lysates were made in Passive Lysis buffer (Promega) and Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using a dual-luciferase kit (Promega). All experiments were performed at least three times in duplicate. DLL1- or JAG1-dependent NOTCH activation of TP1-luciferase was expressed as fold-activation of signaling induced by NOTCH ligand cells compared with L cells.

NOTCH1 Activation Assay

CHO cells (4 × 105) were plated in a 60-mm plate and the next day transfected with 500 ng of NOTCH1-pCS2+ (a gift of Raphael Kopan), using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's specifications. After incubation overnight in a 37 °C in a CO2 incubator, FuGENE-6 reagent was removed, and cells were allowed to recover in fresh α-MEM containing 10% FBS. After 16 h, cells were incubated with fresh medium containing 2 μm L-685,458 (Sigma) γ-secretase inhibitor dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide or dimethyl sulfoxide alone. L cells, DLL1/L, or JAG1/L cells were released from 10-cm culture dishes using 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen) and 4.5 × 106 of the relevant cells were added to each well. After 6 h of co-culture with or without 2 μm L-685,458 or dimethyl sulfoxide, cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Upstate Technology) with complete mini-protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics), and the lysates were electrophoresed using 7.5% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane at 35 mA overnight, and analyzed by Western blot with anti-Myc antibody 9E10 (Covance, 1:500) or anti-cleaved NOTCH1 antibody Val1744 (Cell Signaling, clone D3B8, 1:1000) (32) or β-actin antibody (Abcam, 1:5000).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

CHO cells (5 × 105) growing in suspension were washed twice with 1 ml of PBS containing 1 mm CaCl2. The cells were fixed with 250 μl of 4% para-formaldehyde for 15 min at RT with rocking. The cells were washed with 1 ml of PBS containing 1 mm CaCl2 twice, and then 1 ml of ligand binding buffer consisting of Hanks' buffered salt solution, pH 7.4, 1 mm CaCl2, 1% (v/v) BSA, and 0.05% NaN3. The cells were incubated with anti-mouse NOTCH1 antibody (8G10, Upstate, 1:10) or anti-mouse NOTCH3 antibody (AF1308, R&D Systems, 1:10) on ice for 20 min, sequentially incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-syrian hamster IgG antibodies (Jackson) or R-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:100) on ice for 20 min. Cells were washed with 0.5 ml of ligand binding buffer twice, and then analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Cell surface DLL1 on L cells or DLL1/L cells was detected using anti-human Delta-like 1 protein antibody (R&D Systems; 1:10) followed with FITC-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibody (Zymed Laboratories Inc.; 1:100) and analyzed by FACScan.

For NOTCH ligand binding analysis, cells were incubated with 100 μl of ligand binding buffer containing azide and 10 μg/ml of DLL1-Fc or JAG1-Fc prepared as described (27). After 1 h at RT, cells were washed twice with 0.5 ml of ligand binding buffer, and incubated with PE-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:100) at RT for 30 min. The cells were then washed twice with 1 ml of ligand binding buffer and analyzed using FACScan.

For the L-PHA (Phaseolus vulgaris leukoagglutinin) binding assay, cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin in PBS and 5 × 105 cells were incubated in 1 μg of fluorescein-labeled L-PHA (Vector) in 50 μl of ligand binding buffer on ice for 15 min. The cells were washed with 0.5 ml of ligand binding buffer twice and analyzed using FACScan.

Preparation of NOTCH1/EGF1–36-MycHis6 Fragments

The mouse Notch1/EGF1–36-MycHis6-IRES-EGFP cDNA was made by insertion of IRES-EGFP from pIRES2-EGFP (Clontech Laboratories) into pSectag2Hygro/Notch1/EGF1–36-MycHis6 (N1/EGF1–36; kind gift of Robert Haltiwanger). The following clones were transfected with N1/EGF1–36: Lec1/vector.C4, Lec1/Lfng-AP.A6, Lec1/Mfng-AP.E11, and Lec8/vector.3.2, Lec8/Lfng-AP.A1, and Lec8/Mfng-AP.H3 cells selected for resistance to 600 μg/ml of hygromycin (Sigma) and sorted by flow cytometry for high EGFP expression. Each transfectant population was grown to ∼90% confluence in 15-cm plates, cultured for 4 days in CHO-SFM-II serum-free medium (Invitrogen), and 100 ml of conditioned medium was collected. After centrifugation at 150 × g for 3 min at RT, the medium was filtered through a 0.22-μm filter. After adding 20 mm NaH2PO4, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm imidazole to the medium, 200 μl of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose beads (Qiagen) was added and the mixture was rotated at 4 °C overnight. The beads were washed with 10 ml of Buffer 1 (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 500 mm NaCl, and 1 mm CaCl2), followed by 0.6 ml of Buffer 2 (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm imidazole). N1/EGF1–36 fragment was eluted with 1 ml of 250 mm imidazole containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, and 0.01% Triton X-100. The eluate was diluted with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2 and protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics) to 10 ml and then incubated with 10 μg of anti-Myc antibody 9E10 conjugated to 100 μl of Protein G beads (Thermo) overnight at 4 °C. The beads were washed 5 times with 0.5 ml of Buffer 3 (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, and 1% Triton X-100). The N1/EGF1–36 fragment was eluted with 600 μl of 0.1 m glycine-HCl, pH 2.8, and neutralized with 1 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and stored at 4 °C. The amount of fragment was determined by Western blot analysis with anti-Myc antibody 9E10 (1:500) compared with known amounts of IgG detected using anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated with HRP (1:10,000; Pierce). Fragments were also analyzed by lectin blot using 10 μg/ml of biotinylated Griffonia (Bandeiraea) simplicifolia lectin II (GSL-II; Vector), biotinylated Lens culinaris agglutinin (LCA; Vector) or biotinylated concanavalin A (ConA; Vector), and HRP-conjugated NeutrAvidin (1:5000; Pierce).

Binding of N1/EGF1–36 to DLL1/L Cells

L cells and DLL1/L cells were harvested using cold Cell Dissociation Reagent (Millipore). Cells (2.5 × 105) were washed 3 times with 0.5 ml of α-MEM containing 10% FCS, and in 0.5 ml of ligand binding buffer twice. Cells were incubated with 4 μl of NOTCH1 fragments (∼100 μg) and 96 μl of ligand binding buffer for 1 h on ice. After washing with 0.5 ml of ligand binding buffer twice, cells were incubated with 0.1 μg/μl of anti-His antibody (Roche Diagnostics) in 50 μl of ligand binding buffer for 30 min on ice. Cells were washed with 0.5 ml of ligand binding buffer twice and incubated with PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Jackson Laboratories; 1:100) for 15 min on ice. Cells were washed 3 times with 0.5 ml of ligand binding buffer and analyzed by FACScan.

RESULTS

LFNG Is Necessary but Not Sufficient to Enhance DLL1-induced NOTCH Signaling in CHO Cells

CHO cells endogenously express NOTCH1 (14, 27), NOTCH2 (27), NOTCH3 (27), and probably NOTCH4, along with small amounts of radical Fringe (RFNG) and LFNG, but not MFNG (24, 25). The parental CHO line (Pro−5) and the glycosylation mutants derived from it, lack transcripts for B4galt6, but express the other five known B4GALT to transfer Gal to GlcNAc in mammals (33). B4GALT6 is not required for the synthesis of tri- or tetrasaccharide O-fucose glycans on NOTCH1 in CHO cells (14, 24). The cells used in this study, with the respective FNG activity expressed in each, are given in Table 1. Both LFNG and MFNG tagged with AP at the C terminus were secreted into the medium (9), which was used as a measure of relative expression (Table 1), as described previously (9, 24). FNG β3GlcNAcT activity with Fuc-O-p-nitrophenyl phosphate was also measured in conditioned medium for several lines (Table 2). This was a less accurate measure of expression level because of the background expression of LFNG and RFNG in CHO cells (24), and because LFNG is a much more active enzyme in vitro than MFNG (13). Nevertheless, it is apparent that the MFNG/DDA mutation reduced activity. The O-fucose glycans of a NOTCH1 ECD fragment from CHO and CHO glycosylation mutants expressing FNG were previously shown to carry the O-fucose glycans as indicated in Table 1 (24).

TABLE 2.

Fringe activity in stable transfectants

The unit of Fringe activity is 3H cpm/0.43 ml of conditioned medium when 3 × 105 cells were cultured in 1.5 ml of serum-free medium for 2 days. These results were from one experiment. In 3 separate experiments, CHO/LFNG.2.5A activity varied from 4193 to 6443 cpm and background varied from 235 to 304 cpm. Symbols are as described as in Table 1.

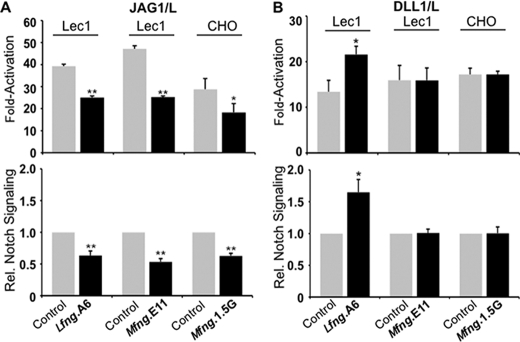

LFNG or MFNG cause reduced NOTCH signaling induced by JAG1 in CHO and Lec1 cells (24). Lec1 cells have defective N-glycan synthesis but normal O-glycan synthesis (34). We confirmed previous results using an improved NOTCH signaling reporter TP1-luciferase (28) in the co-culture assay (Fig. 1A). This reporter gives ∼30–40-fold activation of signaling through endogenous CHO NOTCH receptors by JAG1/L cells and ∼10–20-fold activation by DLL1/L cells (27). Lec1 cells responded to DLL1/L cells and NOTCH signaling was markedly increased in Lec1/Lfng cells (Fig. 1B). By contrast, Lec1/Mfng cells did not show enhanced signaling (Fig. 1B). The same result was obtained with CHO/Mfng cells. Transient overexpression of Mfng introduced into Lec1/Mfng stable transfectants also did not increase DLL1-induced signaling (data not shown). This contrasts with the enhanced NOTCH signaling observed with Lfng (Fig. 1B) and with Mfng in 3T3 cells overexpressing NOTCH1 (23). However, 3T3 and other cell types expressing only endogenous levels of NOTCH receptors behave similarly to CHO and Lec1 and do not exhibit markedly enhanced DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling from Mfng (22, 23, 25, 35).

FIGURE 1.

DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling is enhanced by LFNG but not MFNG in CHO and Lec1 cells. A, the histogram shows the fold-activation (top) and relative NOTCH signaling of normalized luciferase units (bottom) in CHO and Lec1 cells expressing vector (Control), LFNG or MFNG as indicated, and stimulated by L cells versus JAG1/L cells. B, the same as A except that signaling reflects stimulation by DLL1/L cells versus L cells. Error bars represent S.D.; n ≥ 4. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05.

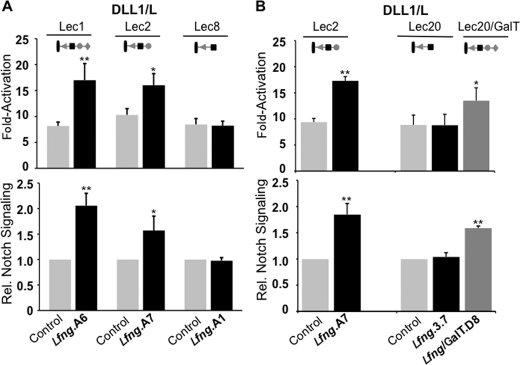

The Lec2 CHO mutant does not add sialic acid to O-fucose (and other) glycans due to an inactive CMP-sialic acid (CMP-NeuAc) transporter that prevents CMP-NeuAc from being translocated into the Golgi (36). DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling in Lec2 cells was increased by Lfng (Fig. 2A), and therefore sialic acid is not essential for LFNG to enhance NOTCH signaling. Lec8 CHO glycosylation mutants have an inactivating mutation in a UDP-Gal transporter that reduces UDP-Gal translocation into the Golgi, thereby preventing galactosylation of glycoproteins (30). Lec8/Lfng cells did not exhibit increased DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling, in contrast to control Lec1/Lfng and Lec2/Lfng cells (Fig. 2A). We also tested Lec20/Lfng cells, which lack B4GALT1 activity (33). Lec20/Lfng cells also exhibited no increase in DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling, similar to Lec8/Lfng cells (Fig. 2B). However, Lec20/Lfng cells corrected with a B4galt1 cDNA were rescued for NOTCH signaling (Fig. 2B). The combined results show that the addition of Gal to O-fucose glycans is required for LFNG to modulate DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling in CHO cells, as found previously for JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling (24).

FIGURE 2.

Galactose is required for LFNG enhancement of DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling. A, fold-activation (top) and relative NOTCH signaling (bottom) in Lec1, Lec2, or Lec8 cells stably expressing vector (Control) or LFNG stimulated by DLL1/L versus L cells. B, fold-activation (top) or relative NOTCH signaling (bottom) in vector control or LFNG expressing Lec2, Lec20, or Lec20 cells corrected with a B4galt1 cDNA stimulated by DLL1/L versus L cells. Error bars represent S.D.; n ≥ 4 experiments with 2–3 replicates per experiment. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Symbols represent O-fucose glycans on NOTCH: triangle, fucose; black square, GlcNAc; gray circle, Gal; diamond, sialic acid.

DLL1-induced NOTCH Signaling Is Enhanced by Mfng in the Absence of Gal on O-Fucose Glycans

JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling is refractory to MFNG when Gal is absent from O-fucose glycans (24). We obtained the same results for JAG1-induced signaling in Lec8/Mfng and Lec20/Mfng cells using the improved co-culture NOTCH signaling assay (Fig. 3). Two independent Lec2/Mfng cell lines had reduced NOTCH signaling induced by JAG1, whereas three independent Lec8/Mfng lines exhibited no reduction in NOTCH signaling in response to JAG1 (Fig. 3A). Two Lec20/Mfng lines gave a similar result (Fig. 3A). However, when the three Lec8/Mfng lines were examined for DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling, they all showed increased NOTCH activation (Fig. 3B). A similar result was obtained with Lec20/Mfng cells (Fig. 3B). This suggested an inhibitory effect of Gal following MFNG modulation of DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling. Consistent with this, Lec2/Mfng cells behaved like Lec1/Mfng and CHO/Mfng cells, all of which carry Gal on O-fucose glycans (24). Lec2/Mfng cells did not exhibit increased signaling in response to DLL1 (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Galactose is required for MFNG to inhibit JAG1-induced signaling, but prevents MFNG enhancement of DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling. A, relative NOTCH signaling in Lec2, Lec8, or Lec20 cells expressing vector (Control) or Mfng stimulated by JAG1/L versus L cells. B, the effects of DLL1/L cells on the same cell lines. Error bars represent S.D.; n ≥ 4 experiments with 3 replicates per experiment. **, p < 0.01. Lec20/Mfng2.6 was 2 experiments with 3 replicates each. C, Western blot analysis of activated, cleaved NOTCH1 (Val1744), full-length NOTCH1 (9E10), and β-actin from Lec2, Lec8, or Lec20 cells expressing vector or Mfng stimulated by DLL1/L, JAG1/L, or L cells, respectively, in the presence or absence of γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI). The gels are representative of replicates from two independent experiments. Symbols are as described in the legend to Fig. 2 and represent O-fucose glycans on NOTCH/EGF repeats.

This unexpected result was investigated using an alternative NOTCH signaling assay. The Val1744 monoclonal antibody detects activated NOTCH1 following cleavage by γ-secretase (32). To investigate the effect of MFNG on NOTCH1 activation in Lec2, Lec8, and Lec20 cells, mouse NOTCH1 was transfected into vector and Mfng cells, cultured overnight, and co-cultured with DLL1/L or JAG1/L cells for 6 h in the presence or absence of a γ-secretase inhibitor, and subjected to Western blot analysis. Enhanced levels of activated NOTCH1 (Act. N1) compared with full-length NOTCH1 (FL) were apparent for both endogenous and exogenous NOTCH1 from Lec8/Mfng and Lec20/Mfng cells compared with control and Lec2/Mfng cells (Fig. 3C). By contrast, activated NOTCH1 levels changed little in Lec8/Mfng and Lec20/Mfng following co-culture with JAG1/L cells (Fig. 3C) compared with the marked reduction in activated NOTCH1 from Lec2/Mfng cells. Thus, both the reporter and the activated NOTCH signaling assays showed that MFNG enhances DLL1-induced signaling and does not significantly alter JAG1-induced signaling when Gal is absent from O-fucose glycans.

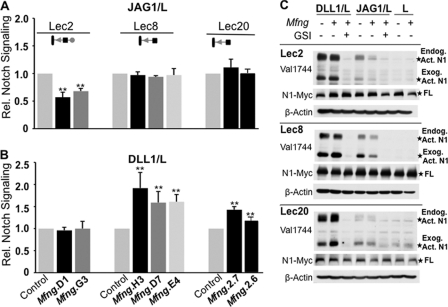

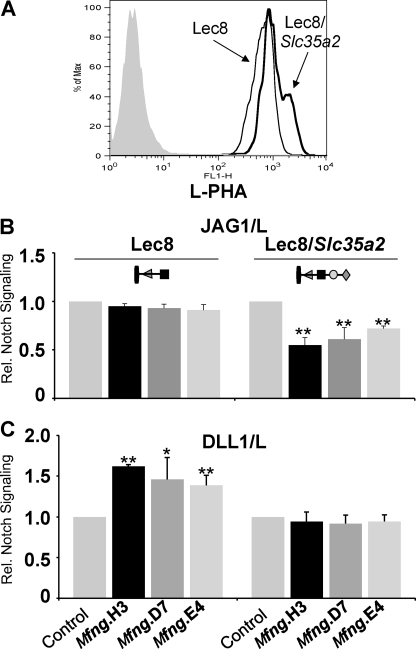

To determine that the enhanced NOTCH signaling induced by DLL1 in Lec8/Mfng cells was due to the absence of Gal, a plasmid encoding CHO UDP-Gal transporter Slc35a2 was transfected into Lec8/Mfng and control cells. Complementation of the Lec8 mutation was confirmed by flow cytometry using L-PHA that recognizes complex-type N-glycans containing Gal (Fig. 4A). Lec8 cells expressing Mfng and SLC35A2 had decreased NOTCH signaling induced by JAG1 (Fig. 4B), as expected (24). In addition, the increased DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling in Lec8/Mfng cells was abrogated after complementation of Lec8 by Slc35a2 (Fig. 4C). The combined data suggest that Gal in O-fucose glycans interferes with Mfng modulation of DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling.

FIGURE 4.

Rescue of MFNG effect in Lec8 by SLC35A2. A, flow cytometry profiles of L-PHA binding to Lec8 cells with or without transient transfection of Slc35a2. B, relative NOTCH signaling in Lec8 cells expressing vector (Control), MFNG, or MFNG + SLC35A2 stimulated by JAG1/L versus L cells. C, the same experiment as B in transfectants stimulated by DLL1/L versus L cells. Error bars represent S.D.; n ≥ 4 experiments with 2–3 replicates each. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Symbols are as described in the legend to Fig. 2 and represent O-fucose glycans on NOTCH/EGF repeats.

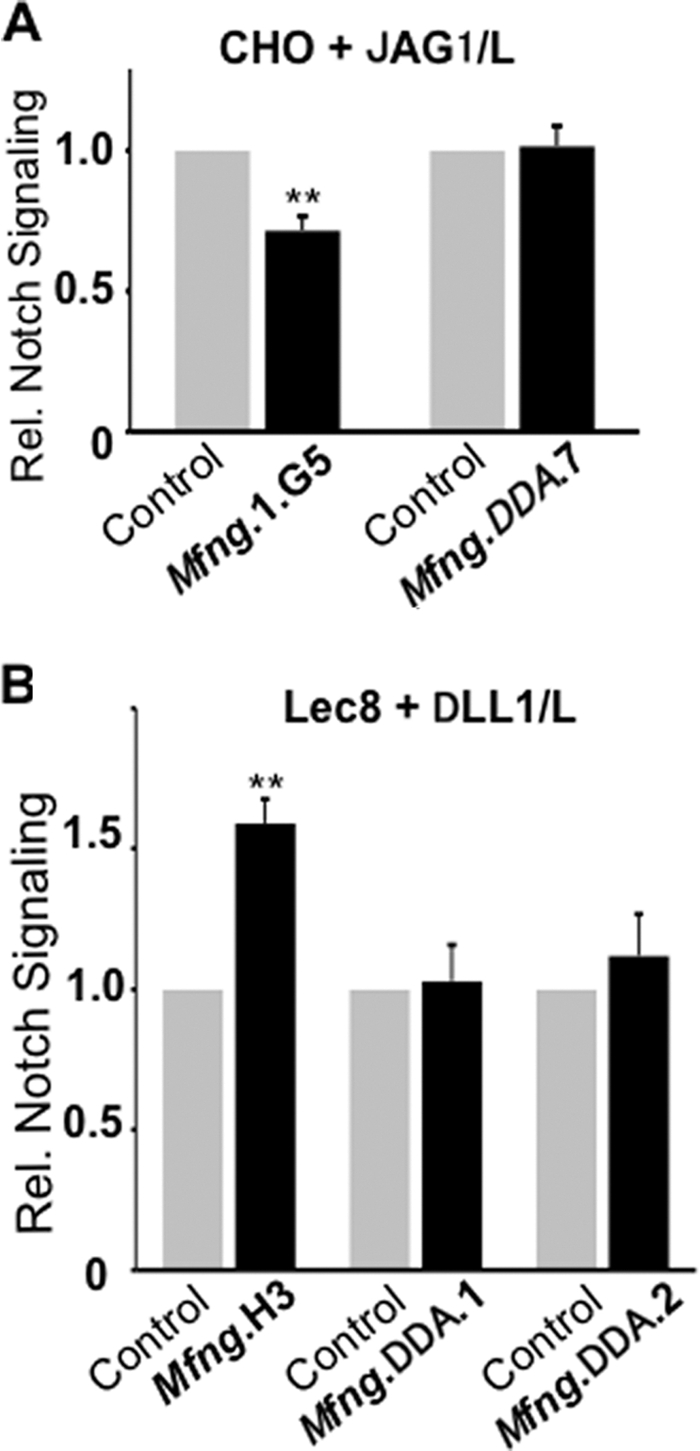

MFNG Activity Is Required to Enhance DLL1-induced NOTCH Signaling in Lec8 Cells

To investigate whether effects on NOTCH signaling observed in Lec8/Mfng cells required β3GlcNAcT activity, the conserved DDD motif at amino acids 142–144 in MFNG was converted to DDA. We confirmed that MFNG/DDA was inactive (Table 2). When CHO cells expressing MFNG/DDA were tested in the co-culture assay, there was no inhibition of JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling (Fig. 5A), consistent with our previous results (24). In Lec8 cells expressing MFNG/DDA, there was also no increased DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling (Fig. 5B). Therefore, β3GlcNAcT activity was essential for MFNG to modulate DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling in Lec8 cells. Moreover the results in Figs. 4 and 5 indicate that the enhancement of DLL1-induced signaling by MFNG occurs when NOTCH carries only GlcNAcβ1,3-fucose not masked with Gal.

FIGURE 5.

Fringe glycosyltransferase activity is required for the MFNG effect on NOTCH signaling. A, the histogram shows relative NOTCH signaling based on normalized luciferase ratios in CHO cells expressing vector (Control), wild-type MFNG (MFNG.DDD), or mutant MFNG (MFNG.DDA) stimulated by JAG1/L versus L cells. B, the same experiment in Lec8 cells expressing vector (Control), MFNG wild-type, or mutant MFNG.DDA with stimulation by DLL1/L versus L cells. Error bars represent S.D.; n ≥ 4 experiments with 2–3 replicates each. **, p < 0.01. Symbols are as described in the legend to Fig. 2 and represent O-fucose glycans on NOTCH/EGF repeats.

Effects of MFNG and LFNG on the Binding of Soluble JAG1-Fc and DLL1-Fc to NOTCH

We show that MFNG and LFNG differentially affect DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling, depending on the presence of Gal on O-fucose glycans. To investigate whether NOTCH ligand binding is also differentially regulated by MFNG versus LFNG, we performed binding assays using soluble NOTCH ligands DLL1-Fc and JAG1-Fc. Lec1 and Lec8 Mfng and Lfng transfectants express similar levels of cell surface NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 (Fig. 6A). Both MFNG and LFNG decreased the binding of JAG1-Fc to the surface of Lec1 cells. This is consistent with their ability to reduce NOTCH signaling induced by JAG1 (Fig. 1A). The shift in binding was small but reproducible (Fig. 6B, Table 3). LFNG and MFNG had no effect on the binding of JAG1-Fc to Lec8 cells (Fig. 6B, Table 3). This was consistent with the inability of both FNG activities to inhibit JAG1-induced signaling in the absence of Gal.

FIGURE 6.

NOTCH receptor expression and NOTCH ligand binding to cells expressing Mfng or Lfng. A, the surface expression of NOTCH1 (8G10) and NOTCH3 (AF1308) on Lec1 or Lec8 cells expressing vector (thin line), Lec1 or Lec8 cells expressing Lfng or Mfng as indicated (bold lines). B, the binding of soluble JAG1-Fc or DLL1-Fc to the surface of the cells shown in A. Thin lines indicate cells expressing vector. Bold lines indicate cells expressing Lfng or Mfng, respectively. Representative results of ≥2 experiments are shown.

TABLE 3.

Effects of LFNG and MFNG on NOTCH ligand binding

Values are % relative MFI compared to Lec1/pMirB or Lec8/pMirb vector controls. Errors are S.D., n = 3.

| Cell line | NOTCH ligand | MFNG | LFNG | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lec1 | JAG1-Fc | 68 ± 14a | 79 ± 4a | Decreased |

| Lec8 | JAG1-Fc | 110 ± 23 | 123 ± 17 | Unchanged |

| Lec1 | DLL1-Fc | 148 ± 18a | 138 ± 19a | Increased |

| Lec8 | DLL1-Fc | 141 ± 9a | 164 ± 63 | Increased (MFNG) |

| Variable (LFNG) |

a p < 0.05.

LFNG increased the binding of DLL1-Fc to Lec1 cells (Fig. 6B), as expected from its ability to increase DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2). However, MFNG also increased DLL1-Fc binding to Lec1 cells (Fig. 6B, Table 3), although MFNG did not enhance NOTCH signaling in Lec1 cells (Fig. 1B).

Binding of DLL1-Fc was highly variable to Lec8/Lfng cells but was reproducibly increased to Lec8/Mfng cells (Table 3), consistent with the increased response of this line to DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling. The increase in DLL1-Fc binding observed with Lec8/Mfng cells (mean fluorescence index 143 ± 16) was not observed for Lec8 cells expressing inactive Mfng/DDA (mean fluorescence index 104 ± 3). Thus, with the exception of the enhanced DLL1-Fc binding to Lec1/MFNG cells, binding of soluble NOTCH ligands reflected their ability to alter NOTCH signaling strength.

Binding of Notch1 ECD to DLL1/L Cells

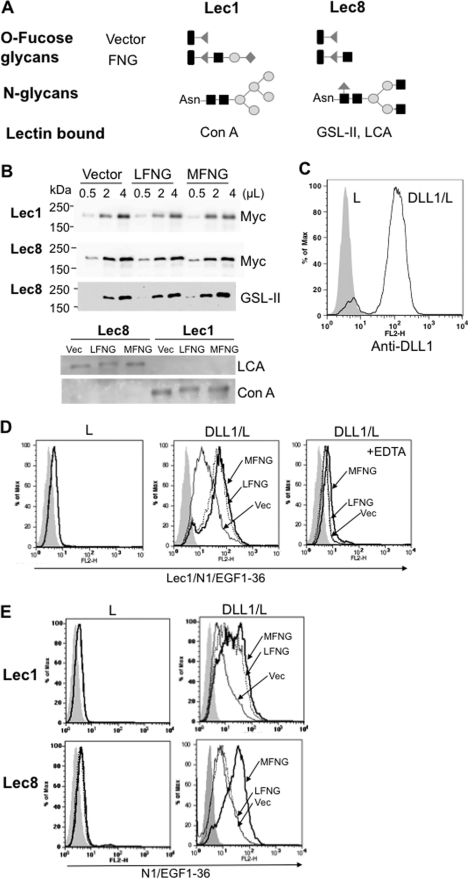

To investigate effects of MFNG and LFNG on NOTCH1 ECD binding to DLL1, the N-terminal domain of NOTCH1 containing EGF repeats 1–36 with a Myc-His6 C-terminal tag was produced in Lec1 and Lec8 cells expressing vector or Lfng or Mfng and binding to DLL1/L cells was examined. The predominant O-fucose glycans and N-glycans present on N1/EGF1–36 from the different cells are shown (Fig. 7A). Equivalent amounts of NOTCH1 were purified from each line and bound the lectins predicted by their N-glycan glycosylation defect (Fig. 7B). DLL1/L cells were characterized by an anti-DLL1 antibody (Fig. 7C). N1/EGF1–36 prepared from Lec1 cells expressing vector, Lfng, or Mfng did not bind to L cells (Fig. 7D). N1/EGF1–36 modified by LFNG or MFNG in Lec1 bound similarly to DLL1/L cells and much better than N1/EGF1–36 from Lec1/vector cells (Fig. 7D). Binding was inhibited by chelation of Ca2+ by EDTA (Fig. 7D). By contrast, NI/EGF1–36 from Lec8/Lfng cells bound less well than NI/EGF1–36 from Lec8/Mfng cells (Fig. 7E). Consistent with NOTCH signaling and ligand binding assays, NOTCH1 modified by MFNG interacted significantly better with DLL1 than NOTCH1 modified by LFNG. Most importantly, this result is from soluble NOTCH rather than membrane-bound NOTCH and therefore eliminates concerns that our findings reflect a cell background effect.

FIGURE 7.

Binding of N1/EGF1–36-MycHis6 carrying different O-fucose glycans to DLL1/L cells. A, structure of predominant O-fucose glycans and N-glycans on NOTCH1 ECD produced in Lec1 and Lec8 CHO cells. Symbols are as described in the legend to Fig. 2. B, Western blots of mouse N1/EGF1–36-MycHis6 (N1/EGF1–36) prepared from Lec1 or Lec8 cells expressing vector, Lfng, or Mfng. N1/EGF1–36 was detected by anti-Myc antibody 9E10 or lectin (GSL-II and LCA detected terminal GlcNAc on N1/EGF1–36 from Lec8; ConA detected high mannose N-glycans on N1/EGF1–36 from Lec1. C, surface expression of DLL1 on L cells and DLL1/L cells. D, the binding of N1/EGF1–36 prepared from Lec1 expressing vector (thin line), Lfng (dotted line), or Mfng (bold line) to L or DLL1/L cells in the presence or absence of 5 mm EDTA. E, binding of N1/EGF1–36 prepared from Lec1 or Lec8 expressing vector (thin lines), Lfng (dotted lines), or Mfng (bold lines) to L or DLL1/L cells. Binding was detected with anti-His antibody. Profiles are representative of ≥2 experiments.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that, in CHO cells, the addition of Gal to O-fucose glycans generated by LFNG or MFNG is necessary to inhibit JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling (24), and embryos lacking B4GALT1 exhibit subtle NOTCH signaling defects during somitogenesis (24). In this article, we show that Gal on O-fucose glycans is also a regulator of DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling. Our findings for both JAG1 and DLL1 are summarized in Table 4. Using a co-culture assay with increased sensitivity for NOTCH signaling (27), we confirmed that the action of LFNG or MFNG, and the addition of Gal to O-fucose glycans, is required to inhibit JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling (Fig. 1). We also showed that cells with NOTCH having Gal on O-fucose glycans exhibit reduced binding of JAG1-Fc (Fig. 6 and Table 3). Therefore, NOTCH binding of soluble JAG1-Fc, which is thought to exist as a dimer (22), reflected the effects of Gal observed on JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling in the presence of LFNG or MFNG. In Drosophila, the addition of Gal to O-fucose glycans on NOTCH EGF repeats modified by Fringe does not influence the reduced binding of NOTCH ECD to Serrate, the homologue of JAG1 (37). However, Fringe-generated O-fucose glycans from Drosophila may carry a glucuronic acid (38) and the effect of this modification on ligand binding or NOTCH signaling has not been investigated.

TABLE 4.

Effects of Gal on Fringe modulation of NOTCH signaling

A summary of data from this paper and Ref. 22. NC indicates no change in NOTCH signaling when FNG is expressed compared to vector control. The “↓” means decreased signaling induced by JAG1 and “↑” means increased signaling induced by DLL1. Symbols are as described as in Table 1 represent O-fucose glycans on NOTCH EGF repeats.

Previous studies have shown that both DLL1-induced NOTCH1 signaling and soluble DLL1 ligand binding are increased by overexpression of all three Fringe genes in 3T3 cells overexpressing exogenous NOTCH1 (22, 23). We show here that LFNG is necessary, but not sufficient, to enhance DLL1-induced signaling of endogenous NOTCH receptors of CHO cells (Fig. 2). Thus Lec8 and Lec20 CHO mutants, which are differently defective in adding Gal to O-fucose glycans (22), both failed to exhibit an effect of LFNG on DLL1 signaling in co-culture. The increased DLL1 signaling caused by LFNG in CHO or Lec1 cells (Gal present on O-fucose glycans) is reflected in increased DLL1 binding, and DLL1 binding becomes highly variable in Lec8 cells, in the absence of Gal on O-fucose glycans (Table 3).

MFNG also enhanced DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling but the presence of Gal on O-fucose glycans was not required (Fig. 3). In fact, it was inhibitory. Thus, parent CHO and Lec1 cells, which have Gal on O-fucose glycans, signaled well when induced by DLL1. However, NOTCH signaling was not enhanced in CHO/Mfng or Lec1/Mfng cells, as observed by others in cells expressing only endogenous NOTCH receptors (22, 23). Rather, MFNG enhanced DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling in Lec8 and Lec20 cells suggesting that extension of GlcNAcβ1,3Fuc-O-glycans by Gal inhibits DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling. This new finding was confirmed in several transfectants by two NOTCH signaling assays, and rescue of Gal deficiency. The increase in DLL1-induced signaling by MFNG in Lec8 and Lec20 cells was reflected in an increase in DLL1-Fc binding to Lec8/Mfng cells and increased binding of soluble N1/EGF1–36 from Lec8/Mfng cells to DLL1/L cells. The latter result is most important because it is independent of the cellular environment. The fact that Gal is required for LFNG to enhance DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling, whereas Gal inhibits the ability of MFNG to enhance DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling, suggests that MFNG and LFNG modify distinct complements of EGF repeats on NOTCH. This would be consistent with other reports of differences between LFNG and MFNG (15, 21, 25). Attempts to identify such differences using radiolabeled GlcNAc and NOTCH1 ECD fragments were difficult to interpret. Future efforts will focus on a mass spectrometry strategy that looks very promising (39).

One difference between MFNG and LFNG is the number of predicted N-glycosylation sites: two in MFNG and one in LFNG. The first site is conserved in both in human and mouse. Based on in vitro AP and FNG assays of concentrated conditioned medium, MFNG had a similar activity in CHO, Lec1, and Lec8 cells (Table 1), but this was about 10-fold lower than LFNG, as previously observed with affinity purified enzymes (13, 31). Nevertheless, the effects of MFNG and LFNG on JAG1-induced NOTCH signaling were similar. The different effects of MFNG and LFNG on DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling were apparently not related to levels of activity but to whether O-fucose glycans carried Gal (Table 4). Thus, whereas LFNG enhanced DLL1-induced NOTCH signaling in CHO and Lec1 cells, it caused no enhancement in Lec8 or Lec20 cells when Gal was absent from O-fucose glycans. By contrast, MFNG caused enhanced NOTCH signaling only when Gal was absent. It will be important in the future to determine the nature of the O-fucose glycan on each EGF repeat of endogenous NOTCH receptors when modified by LFNG versus MFNG.

Acknowledgments

We thank Subha Sundaram, Wen Dong, and Huimin Shang for excellent technical assistance. We also thank all those who provided plasmids and cell lines (see “Experimental Procedures”).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 95022 from the NCI (to P. S.) and Albert Einstein Cancer Center Grant PO1 13330.

- ECD

- extracellular domain

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor-like

- MFNG

- Manic Fringe

- LFNG

- Lunatic Fringe

- RFNG

- Radical Fringe

- AP

- alkaline phosphatase

- MEM

- minimal essential medium

- L-PHA

- P. vulgaris leukoagglutinin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Artavanis-Tsakonas S., Muskavitch M. A. (2010) Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 92, 1–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kopan R., Ilagan M. X. (2009) Cell 137, 216–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bolós V., Grego-Bessa J., de la Pompa J. L. (2007) Endocr. Rev. 28, 339–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rampal R., Luther K. B., Haltiwanger R. S. (2007) Curr. Mol. Med. 7, 427–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koch U., Radtke F. (2010) Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 92, 411–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stanley P., Okajima T. (2010) Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 92, 131–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Panin V. M., Papayannopoulos V., Wilson R., Irvine K. D. (1997) Nature 387, 908–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Irvine K. D., Vogt T. F. (1997) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9, 867–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnston S. H., Rauskolb C., Wilson R., Prabhakaran B., Irvine K. D., Vogt T. F. (1997) Development 124, 2245–2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen B., Bashirullah A., Dagnino L., Campbell C., Fisher W. W., Leow C. C., Whiting E., Ryan D., Zinyk D., Boulianne G., Hui C. C., Gallie B., Phillips R. A., Lipshitz H. D., Egan S. E. (1997) Nat. Genet. 16, 283–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moloney D. J., Panin V. M., Johnston S. H., Chen J., Shao L., Wilson R., Wang Y., Stanley P., Irvine K. D., Haltiwanger R. S., Vogt T. F. (2000) Nature 406, 369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brückner K., Perez L., Clausen H., Cohen S. (2000) Nature 406, 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rampal R., Li A. S., Moloney D. J., Georgiou S. A., Luther K. B., Nita-Lazar A., Haltiwanger R. S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42454–42463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moloney D. J., Shair L. H., Lu F. M., Xia J., Locke R., Matta K. L., Haltiwanger R. S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9604–9611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shao L., Moloney D. J., Haltiwanger R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7775–7782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haines N., Irvine K. D. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 786–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Evrard Y. A., Lun Y., Aulehla A., Gan L., Johnson R. L. (1998) Nature 394, 377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang N., Gridley T. (1998) Nature 394, 374–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Visan I., Tan J. B., Yuan J. S., Harper J. A., Koch U., Guidos C. J. (2006) Nat. Immunol. 7, 634–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stanley P., Guidos C. J. (2009) Immunol. Rev. 230, 201–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tan J. B., Xu K., Cretegny K., Visan I., Yuan J. S., Egan S. E., Guidos C. J. (2009) Immunity 30, 254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hicks C., Johnston S. H., diSibio G., Collazo A., Vogt T. F., Weinmaster G. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 515–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang L. T., Nichols J. T., Yao C., Manilay J. O., Robey E. A., Weinmaster G. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 927–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen J., Moloney D. J., Stanley P. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 13716–13721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shimizu K., Chiba S., Saito T., Kumano K., Takahashi T., Hirai H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 25753–25758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen J., Lu L., Shi S., Stanley P. (2006) Gene Expr. Patterns 6, 376–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stahl M., Uemura K., Ge C., Shi S., Tashima Y., Stanley P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13638–13651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Strobl L. J., Höfelmayr H., Stein C., Marschall G., Brielmeier M., Laux G., Bornkamm G. W., Zimber-Strobl U. (1997) Immunobiology 198, 299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Russo R. N., Shaper N. L., Shaper J. H. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 3324–3331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oelmann S., Stanley P., Gerardy-Schahn R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26291–26300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luther K. B., Schindelin H., Haltiwanger R. S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3294–3305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huppert S. S., Le A., Schroeter E. H., Mumm J. S., Saxena M. T., Milner L. A., Kopan R. (2000) Nature 405, 966–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee J., Sundaram S., Shaper N. L., Raju T. S., Stanley P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13924–13934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. North S. J., Huang H. H., Sundaram S., Jang-Lee J., Etienne A. T., Trollope A., Chalabi S., Dell A., Stanley P., Haslam S. M. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5759–5775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rampal R., Arboleda-Velasquez J. F., Nita-Lazar A., Kosik K. S., Haltiwanger R. S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32133–32140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eckhardt M., Gotza B., Gerardy-Schahn R. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20189–20195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okajima T., Xu A., Irvine K. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42340–42345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aoki K., Porterfield M., Lee S. S., Dong B., Nguyen K., McGlamry K. H., Tiemeyer M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30385–30400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rana N. A., Nita-Lazar A., Takeuchi H., Kakuda S., Luther K. B., Haltiwanger R. S. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31623–31637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]