Background: Apoptotic cells release vesicles, which expose “eat-me” signals.

Results: Vesicles originated from endoplasmic reticulum expose immature glycoepitopes and are preferentially phagocytosed by macrophages.

Conclusion: Immature surface glycoepitopes serve as “eat-me” signals for the clearance of apoptotic vesicles originated from endoplasmic reticulum.

Significance: Understanding the distinction by macrophages of apoptotic blebs may provide new insights into clearance-related diseases.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Glycosylation, Macrophages, Phagocytosis, Sialic Acid, Blebs, Clearance, Glycopattern, SLE, Sialidase

Abstract

Inappropriate clearance of apoptotic remnants is considered to be the primary cause of systemic autoimmune diseases, like systemic lupus erythematosus. Here we demonstrate that apoptotic cells release distinct types of subcellular membranous particles (scMP) derived from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or the plasma membrane. Both types of scMP exhibit desialylated glycotopes resulting from surface exposure of immature ER-derived glycoproteins or from surface-borne sialidase activity, respectively. Sialidase activity is activated by caspase-dependent mechanisms during apoptosis. Cleavage of sialidase Neu1 by caspase 3 was shown to be directly involved in apoptosis-related increase of surface sialidase activity. ER-derived blebs possess immature mannosidic glycoepitopes and are prioritized by macrophages during clearance. Plasma membrane-derived blebs contain nuclear chromatin (DNA and histones) but not components of the nuclear envelope. Existence of two immunologically distinct types of apoptotic blebs may provide new insights into clearance-related diseases.

Introduction

During apoptotic death the surfaces of apoptotic remnants, including apoptotic blebs, are modified due to oxidative processes resulting in the appearance of immunologically “novel” autoantigens (1). An inefficient clearance of apoptotic cell material (shrunken apoptotic cells, apoptotic bodies or subcellular membranous particles (scMP)2) will result in the accumulation of secondary necrotic remnants that release modified and potentially pro-inflammatory contents into the extracellular milieu. It is common belief that inappropriate clearance of apoptotic cells can lead to the accumulation of modified autoantigens in tissues that foster autoimmune diseases (2).

Unlike necrosis reportedly eliciting inflammatory responses (3), apoptosis mainly displays anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties (4). Apoptotic cells consecutively expose “eat-me” signals like phosphatidylserine (5) and altered glycoepitopes (6), important for early and late clearance, respectively. Artificially desialylated lymphocytes mimic a late apoptotic glycocalyx and are effectively cleared by human macrophages (7).

The mechanism(s) modifying the glycocalyx are still elusive. We propose that (i) apoptozing cells may change the glycosylation of de novo synthesized glycoconjugates. (ii) internal membranes containing immature glycoproteins (GP) may become exposed and (iii) mature GP may get modified by glycosidases (e.g. sialidases) in situ.

To avoid confusion we introduced the term scMP for blebs that obviously had been released into the supernatant from the surfaces of apoptotic cells. The membranous structure formed by late apoptotic cells will be referred to as the big membranous bubble (bMB) (supplemental Fig. S1).

Here we demonstrate that apoptotic cells release distinct types of scMP derived from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or plasma membrane. Both exhibit desialylated glycotopes resulting from surface exposure of immature ER-derived GP or from surface-borne sialidase activity, respectively. We addressed molecular mechanisms of GP redistribution during apoptosis and observed that sialidase activity is activated by caspase-dependent mechanisms. Plasma membrane-derived bMB and scMP contain chromatin but not the nuclear envelope and ER-derived scMP are prioritized by macrophages during clearance. The understanding of the immunological distinction by macrophages of ER and plasma membrane derived apoptotic blebs may provide new insights into clearance-related diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Isolation of Cells

We employed human leukemia Jurkat T-cells, human HeLa cells, and CD95 positive human breast cancer cells MCF-7, as well as primary human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) and monocyte-derived macrophages from healthy volunteers for our experiments. Peripheral blood mono-nuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from peripheral anticoagulated blood by LymphoPrep® gradient centrifugation according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Plasticadherent PBMC were then cultured for 7 days in the presence of GM-CSF (100 units/ml) and autologous serum (days 1, 3, and 5) to generate monocyte-derived macrophages. After 7 days of differentiation, these phagocytes usually contain more than 85% phagocytes positive for CD11b, CD14, and CD89.

Induction and Inhibition of Apoptosis

Cell viability was controlled by AnnexinV/PI staining. Apoptosis was induced by etoposide (1 μm, 24 h; Jurkat cells), by irradiation with ultraviolet light type B (UV-B; 180 mJ/cm2 within 60s; Jurkat and HeLa), or by aging (PMN). Caspase inhibitors zVAD-FMK (zVAD, carbobenzoxy-valyl-alanyl-aspartyl-[O-methyl]-fluoro-methyl-ketone,Bachem AG, Bubendorf), zDEVD-FMK, zIETD-FMK and zLEHD-FMK (R&D Systems, Minneapolis) were applied as recommended by the manufacturers.

Cytochemistry

Cytochemistry was performed with standard laboratory methods (8). Analyses employing fluorescence-labeled lectins (9) were performed using an EPICS XLTM (Coulter, Hialeah) or FACS scan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Tunicamycin (1 μm), monensin (1 μm), 2-deoxy-d-glucose (100 mm), cycloheximide (15 μg/ml), and actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) (all from Sigma) were applied according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Transfection of Cells

Transfection of HeLa cells with KDEL receptor-GFP construct was carried out as described previously (10). Transduction with GFP-linked N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferase-2 and SV40 nuclear translocation signal were performed using Organelle LightsTM (Invitrogen) Golgi and nuclear envelope GFP kits, respectively.

Staining with Lectins

Lectins NPL (Narcissus pseudonarcissus lectin), PNA (peanut agglutinin), RCA-I (Ricinus communis agglutinin), PSL (Pisum sativum lectin), were from Lectinotest Laboratory (Ukraine) and VAA (Viscum album agglutinin 1), CEL (Canavalia ensiformis lectin), MAA-II (Maackia amurensis agglutinin II) (a2,3-sialil specific), UEA (Ulex Europeaus Agglutinin I) (specific to terminal fucose) were from Vector Laboratories. For the imaging of bubbling apoptotic cells, 10 μg/ml lectins were added to cultured cells and immediately imaged to achieve optimal S/N ratios (11), non-permebialized cells were used to demonstrate surface-related signals.

Measurement of Sialidase Activity

Sialidase activity was visualized using 5 μm final concentration of the enzymatic substrate 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid (4-MUNA) providing a fluorescent product upon cleavage (12, 13). PM was stained with Vybrant DiI (Invitrogen), ER was stained with ER-TrackerTM Green (BODIPY® FL glibenclamide) (Invitrogen) prior to induction of apoptosis.

Microscopy

Confocal microscopy was performed using PerkinElmer Ultra-View spinning disc confocal on Nikon TE2000-E Ti inverted microscope using ×100 oil-immersion lens (excitation at 488, 568, 647 nm, detection at 650 nm, shown in red and 488 nm, shown in green). Fluorescent microscopy was performed using Zeiss AxioImager A1 with Zeiss AxioCam MRm digital camera. Some images were deconvolved using AutoQuant X2 (MediaCybernetics Inc). ImageJ (NIH) software was used for co-localization analysis and image processing. In-focus rendering of DIC images was done with Helicon Focus. In all cases, microscopy was done observing at least 5 Petri dishes (9 cm) with cells grown to 70–90% confluency for each variant. For quantification at least 1000 cells were counted. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

Determination of Trans-sialidase and Sialidase Activity

Cell trans-sialidase activity toward RBCs was determined using a test based on RBC agglutination with PNA lectin described elsewhere (14) and by their co-incubation at 37 °C for 3 h with cells/conditioned medium or Clostridium perfringens (Sigma) sialidase as controls and standard, respectively.

Caspase inhibitors zVAD-FMK (zVAD, carbobenzoxy-valyl-alanyl-aspartyl-[O-methyl]-fluoro-methyl-ketone, Bachem AG), zDEVD-FMK, zIETD-FMK and zLEHD-FMK (R&D Systems) were applied according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Monoclonal anti-Neu2 and polyclonal anti-Neu1 antibodies were from Abnova, monoclonal anti-Neu2, polyclonal anti-Neu1 and anti-Neu3 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and polyclonal anti-Neu4 antibody was from Proteintech Group. Isoelectric focusing was performed according to Ref. 15.

Phagocytosis Assays

Phagocytosis of scMP was assessed by incubation of PMN-derived scMP with human monocyte-derived macrophages and uningested scMP stained with lectin(s) were analyzed by flow cytometry.

In silico analysis for transmembrane regions was done with HMMTOP and TMHMM. For the prediction of cleavage sites by caspases of sialidases, we employed GrabCas, CASVM, PeptideCutter, and CasCleave and set the cut-off scores >5,0 (GrabCas).

Statistics

Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t test. Three levels of significance were used: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

RESULTS

The Exposure of Galactose/Mannose on the Surfaces of Apoptotic Cells Is Independent of Proteinneogenesis

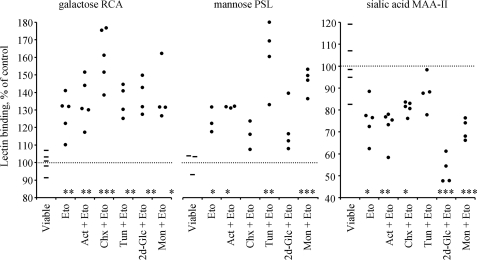

To analyze the mechanisms modifying the glycocalyx we blocked the synthesis pathway for the N-glycans of GP and gangliosides at several steps. Inhibitors of transcription [actinomycin D], translation [cycloheximide], N-glycan synthesis in the ER [tunicamycin, 2-deoxy-d-glucose], and export from Golgi to plasma membrane (PM), [monensin] did not prevent the increased exposure of galactose/mannose and decreased exposure of sialic acid (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Exposure of galactosyl (RCA-binding), mannosyl (PSL-binding), and sialyl (MAA-II-binding) residues on the surface of viable and apoptotic (Eto; etoposide-treated) Jurkat T-cells in the presence of inhibitors of transcription (Actinomycin D, Act), translation (cycloheximide, Chx), or N-glycan synthesis in ER (tunicamycin, Tun, 2-deoxy-d-glucose, 2d-Glc). None of these inhibitors prevented the redistribution of the apoptotic cell-specific glycotopes (Eto), indicating that conventional de novo synthesis is unlikely to be responsible for the exposure of an altered glycotope during apoptosis. Dots represent data for cell populations detected by flow cytometry or cytochemical analyses.

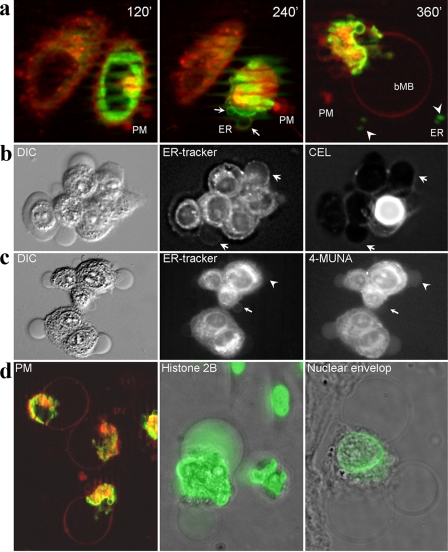

ER-derived Membranes Are Exposed in Late Apoptosis

Next, we transfected HeLa cells with an ER-residing KDEL receptor-GFP fusion construct and stained the PM with the fluorescent hydrophobic dye DiI. When we induced apoptosis with UVB, blebbing of the PM started 120 min after irradiation. After 240 min, the PM constricted and formed a polar conglomerate still connected to the cells' bodies. Concomitantly, ER membranes got exposed and started blebbing. In the supernatant of these cells, distinct scMP were detected that had originated from PM (red) or from ER (green), respectively (Fig. 2a). After 360 min, a bMB was formed that originated from the former PM (red). All blebbing cells produced PM-derived scMP, and most (>90,0%) of the late apoptotic cells demonstrated ER-derived scMP. However, analyzing about 1000 cells from seven independent preparations, we never observed double positive scMP in all our microscopic studies. ER-tracker positive blebs bound NPL (Narcissus pseudonarcissus lectin) and CEL (Canavalia ensiformis lectin), which preferentially recognize ER-related high mannose N-glycans and ER-specific terminally glucosylated N-glycan intermediates (16), respectively (Fig. 2b). Both NPL and CEL signal were co-localized with ER-tracker signal, as shown for permeabilized cells in supplemental Fig. S2.

FIGURE 2.

Apoptotic cells produce distinct types of scMP. a, apoptotic cells form scMP that are derived from the PM (red) or from the ER (green). 120′ after irradiation with UV-B, only PM-derived blebs are generated. Later, ER-derived membranes can be observed on the surface of the cell (arrow) and on scMP (arrowhead), respectively. Finally a big PM-derived bubble (bMB) is formed from PM. b, HeLa cells were stained with ER-tracker™, and apoptosis was induced; after 3 h apoptotic cells were counterstained for immature ER-related glycotopes with CEL. scMP, positive for both ER-tracker and CEL, are indicated by arrows. During apoptosis, ER-related glycoconjugates are exposed on the cell surfaces. The intensely stained cell is a secondary necrotic one, exposing internal glycoepitopes. c, apoptotic cells (like B) were incubated in the medium containing the sialidase substrate 4-MUNA. A scMP positive for ER and negative for sialidase activity is indicated by arrows; a scMP negative for ER and positive for sialidase activity is indicated by arrowheads. During apoptosis sialidase activity is present on the PM and on PM-related scMP, but not on ER-related scMP. d, bMB arises from the PM (DiI staining, red, left panel) and is filled with chromatin-derived antigens (here: histone 2B (middle panel)) in most of the transfected cells. The nuclear envelope, visualized by GFP-linked nesprin-1α, is excluded form the bMB (five preparations utilizing 1000 cells each; right panel). a-d, non-permeabilized non-fixed cells were imaged.

Sialidase Activity and ER-Markers Are Mutually Exclusive

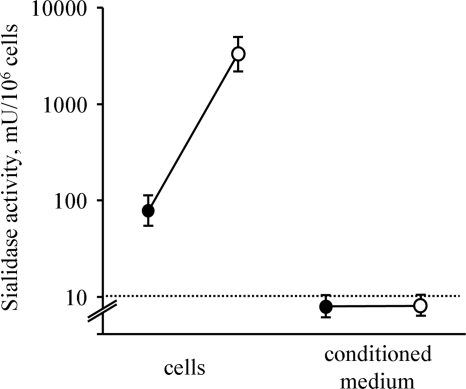

We screened the cells for sialidase activity and observed a reduced surface sialylation and an increased exposure of galactosyl residues on the surfaces of apoptotic cells and their surface-derived scMP. The non-penetrating sialidase substrate 4-MUNA detected sialidase activity on the surfaces of apoptotic cells and of some of the scMP. Sialidase activity and ER-tracker staining of the scMP were mutually exclusive (Fig. 2c). Chromatin-derived histone 2B-GFP fusion proteins were translocated to the cytoplasm during apoptosis and was finally located inside the bMB (Fig. 2d) originating from the former PM (observed in most of the apoptotic cell remnants). Moreover, during late apoptosis nuclear components can mainly be included in apoptotic scMP, (observed in some few of the blebbing cells (supplemental Fig. S3)). After induction with etoposide of apoptosis the trans-sialidase activity of Jurkat cells toward red blood cell surface, GP was increased more than 20-fold (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Sialidase activity of apoptotic cells. Apoptotic cells possess increased sialidase activity trans-acting toward RBC. Viable and apoptotic Jurkat cells or their conditioned medium were co-incubated with RBC for 3 h at 37 °C. RBC were then treated with the lectin PNA (specific for desialylated glycoepitopes) and agglutination was evaluated. Solid and open dots represent activity of intact and apoptotic cells, respectively. Neuraminidase from C. perfringens served as standard. Presented data are mean values of three independent experiments.

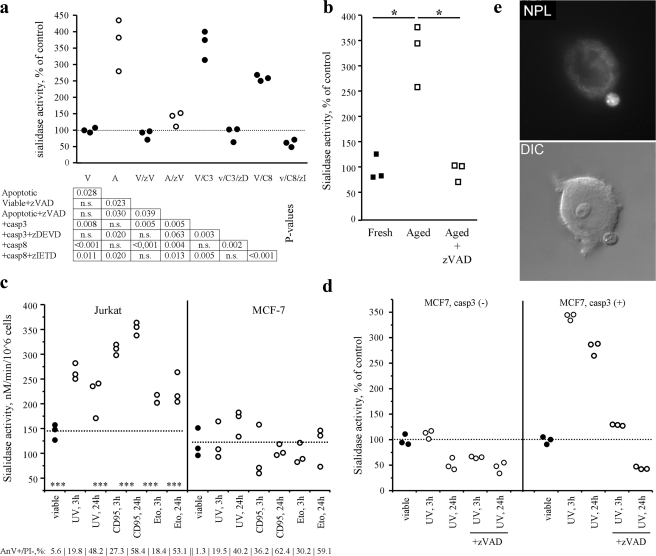

The Increase of Sialidase Activity in Apoptotic Cells Is Caspase-dependent

Treatment with caspases 3 or 8 of cell lysates from viable cells increased the sialidase activities to a level similar to cell lysates generated from apoptotic cells (Fig. 4a). In contrast, the caspase inhibitor zVAD inhibited the generation of sialidase activity in Jurkat cells treated with etoposide or in aged PMN (Fig. 4b). Caspase 3-deficient MCF-7 cells displayed no increased surface sialidase activity during apoptosis (induced by UV-B, etoposide or anti-CD95 Ab; Fig. 4c). Transfection of MCF-7 cells with caspase 3 restored the increase during apoptosis of sialidase activity (Fig. 4d). MCF-7 cells, lacking caspase-3 and increased sialidase activity during apoptosis produced ER-derived scMP upon treatment with UV-B, They also produce two distinct populations of scMP that were positive for ER-tracker or Dil, respectively (Fig. 4e and supplemental Fig. S4).

FIGURE 4.

Caspases are involved in sialidase activation during apoptosis. a, treatment of viable (closed dots) and apoptotic (open dots) Jurkat cell lysates with caspase 3 and 8 resulted in apoptosis-like induction of sialidase activity. Simultaneous treatment with caspase inhibitors demonstrates specificity. Dotted line represents the mean value of viable cell lysates. V, viable; A, apoptotic; zV, zVAD; zD, zDEVD; zI, zIETD; C3 & C8, caspase 3 & 8, respectively. b, sialidase activity on the surfaces of human PMN after aging in the presence of the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD. c, sialidase activity of cells either expressing (Jurkat) or lacking (MCF-7) caspase 3 at different time points after treatment with inducers of apoptosis such as UV-B irradiation (UV, 180mJ/cm2, 60s), anti-CD95 antibodies (CD95, 1 μg/ml), and etoposide (Eto, 1 μm). Caspase 3 is required for the increased sialidase activity during the execution of apoptosis. Receptor-dependent and internal pathways are affected. Dotted lines represent the mean value of viable cells. d, transfection of MCF-7 cells with caspase 3 restored sialidase activation during apoptosis induced by UV-B irradiation, but not during simultaneous treatment with UV-B irradiation and zVAD. The dotted line represents the mean sialidase activity of the viable cell preparation. e, despite lacking detectable sialidase activity upon apoptosis, MCF-7 cells (not expressing caspase 3) produce ER-derived scMP detected by staining with NPL in more than 30% of the blebbing cells. Apoptosis was induced by UV-B irradiation, and images were taken 4 h after induction.

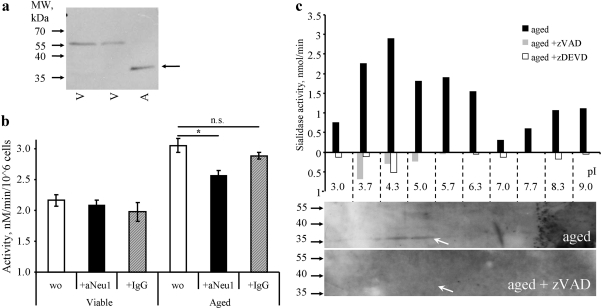

In silico analysis revealed transmembrane regions and a predicted caspase 3 cleavage sites for both Neu1/4 and Neu1 (UniProt: Q5JQI0, cleavage at Asp-135 with score 12,0 by GrabCas), respectively. As Neu2 is exclusively expressed in muscle and Neu3/4 has no high-score cleavage site for executer caspases we focused on Neu1 as the best fitting candidate among the four known human sialidases. Western blot analysis of the lysates from viable or apoptotic PMN showed a band most likely representing a cleavage product of the Neu1 protein in the latter (Fig. 5a). A similar fragment was to be observed after in vitro treatment of cell lysates with caspase 3 (not shown). The depletion of Neu1 abrogated the increased sialidase activity of apoptotic human PMN (Fig. 5b).

FIGURE 5.

Neu 1 is cleaved during apoptosis and contributes to the increased sialidase activity of apoptotic cells. a, Western blot of intact and apoptotic (aged) human PMN cells using a polyclonal antiserum recognizing Neu1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-133813). b, viable and apoptotic (aged) human PMN cell lysates were treated with biotinylated polyclonal anti-Neu1 antisera or control IgG and subsequently precipitated with streptavidin magnetic microbeads. aNeu1, anti Neu1 antiserum. c, PM-enriched fractions of human PMN cells (aged and aged in the presence of caspase inhibitors) were separated by isoelectric focusing, then tubes were sliced and proteins from each fraction were extracted for the determination of the sialidase activity, and for PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Isoelectric focusing of PM-enriched fractions revealed a caspase-dependent sialidase activity in the acidic fractions. The peak of the sialidase activity contained a polypeptide with the molecular mass (∼35 kDa) compatible with the C-terminal fragment of Neu1 (136–415; predicted pI-5.61), which was reactive with a polyclonal antiserum against Neu1 (Fig. 5c).

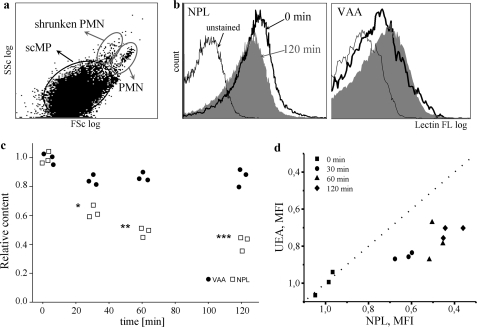

Macrophages Prefer ER-derived scMP

To analysis of phagocytosis of the distinct types of scMP we employed human monocyte-derived macrophages as a validated model for clearance studies (7). scMP derived from aged human PMN served as “prey.” We detected the staining (judged by MFI) of “uncleared” scMP, since it is less reliable to evaluate the amount of ingested scMP, which instantly become degraded inside the phagocytes. The scMP, that are produced by macrophages were also quantified and served as control (despite their amount was extremely low). scMP gated by FSc/SSc data as shown on Fig. 6a were analyzed for fluorescence intensity after staining with lectins. When we co-incubated apoptotic ER- and PM-derived scMP from aged human PMN with human macrophages, ER-derived scMP, endowed with immature ER-related oligomannosidic glycoepitopes, detected with the lectin NPL, were significantly faster cleared by macrophages than the PM-derived ones, exposing PM-related desialylated glycolepitopes characterized by terminal galactose or subterminal fucose residues detected with the lectins VAA (Fig. 6c) or UEA, respectively (Fig. 6d). This was not due to the size difference as macrophages do not display any marked size preference for the engulfment of scMP (supplemental Fig. S5).

FIGURE 6.

ER-derived blebs are preferentially engulfed by macrophages. a, size distribution of scMP population used for further study. b, MFI of scMP population, stained for ER-related glycans (NPL) or desialylated glycans (VAA) before (0 min) and 120 min after incubation with macrophages. A representative histogram is shown. c, blebs generated from apoptotic human PMN cells (24 h aging period), were co-incubated for the indicated time with human monocyte-derived macrophages. Un-ingested scMP were stained with lectins specific for PM-derived desialylated glycoepitopes (VAA, dots) or ER-related immature glycotopes (NPL, squares). Dots and squares represent the MFI (mean fluorescence intensity) value of total population of scMP, n = 3; asterisks represent statistical significance compared with VAA staining. The scMP, that could be produced by macrophages were also quantified and served as control (despite their amount was extremely low). d, relative change of MFI of lectin binding to scMP population during different time intervals of incubation with macrophages. Ulex Europeaus Agglutinin I (UEA) binds subterminal fucosyl residues, exposed after desialylation, while NPL preferentially binds ER-derived glycoepitopes. The MFI of NPL signal decays more rapidly then that of UEA. The dotted line is a symmetrical line representing absence of preference in scMP engulfment. MFI values were normalized to the control.

DISCUSSION

Blockage of the synthesis pathway for N-glycans of GP and gangliosides suggests that de novo synthesis is unlikely to be responsible for the apoptosis-related surface-neoglycotopes. Fluorescence microscopy revealed the formation of distinct apoptotic scMP that originated from the PM or the ER and possess characteristic patterns of glycosylation. PM- and ER-derived scMP expose desialylated and immature mannose-rich glycotopes, respectively. We demonstrated that sialidase activity is focused on the PM and on PM-derived scMP. This finding was also corroborated by staining with VAA (Viscum album lectin 1), a galactosyl-specific lectin, which exclusively bound to ER-tracker negative scMP derived from the PM (supplemental Fig. S6).

Employing a GFP-linked resident Golgi enzyme, N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase-2 (17), we did not observe any exposure on apoptotic cell surfaces of Golgi-derived membranes (not shown). Furthermore, we demonstrated that chromatin-derived histone 2B-GFP fusion proteins are translocated to the cytoplasm during apoptosis and end up in a bMB (Fig. 2d) that originated from the PM. During late stages of apoptosis most chromatin is translocated into a bMB (supplemental Fig. S3). However, we did not observe scMP containing nesprin-1α the marker protein of the nuclear envelop.

Analyzing the following organells: endoplasmic reticulum, endosomes, Golgi, lysosomes, mitochondria, nuclear envelope, nucleus, and peroxisomes (all visualized via transfection with corresponding fluorescent marker proteins) we observed that only endoplasmic reticulum, endosomes, and nuclei are redistributed into the scMP. Additionally, we have observed some organelles (discriminated by DIC microscopy), inside the bMB.

Induction of apoptosis considerably increased a surface-associated sialidase activity, which was not detected in the cells' supernatants. This suggests the action of a cell surface-linked sialidase like Neu-3 (18) or the reportedly surface associated Neu-1 (19). Antisera directed against peptides of Neu-1 and Neu-3 diminished surface-associated sialidase activity (not shown).

Immunoprecipitation studies suggest that Neu-1 may at least partially be responsible for the increased sialidase surface activity observed during apoptosis. As shown by Western blot analyses, Neu-1 is cleaved by caspase 3. However, we do not yet know how (directly or indirectly) this cleavage leads to the activation of Neu-1.

The ability of MCF-7 cells lacking caspase-3 (and thus lacking increased sialidase activity during apoptosis) to produce both ER- and PM-derived scMP, suggests distinct molecular mechanisms involved in the formation of ER-derived scMP and in desialylation of glycoepitopes of PM-derived scMP. The former process was previously reported to be dependent on ROCK (10).

A plethora of receptors and adaptor proteins are involved in the uptake by macrophages of apoptotic cells and their subcellular particles (reviewed in Ref. 20). In general they either recognize phosphatidylserine or altered carbohydrates. Just recently the RAGE receptor has been added to the list of phosphatidylserine-dependent receptors enhancing the efferocytosis of apoptotic cells (21).

Both nucleotides (22) and lipids (23) were shown to act as “eat-me” and “find-me” signals in promotion of apoptotic cell clearance. The surface exposure of the latter was shown to be dependent on caspase 3. Changes of the surface charge (24) as well as carbohydrate content (25) are essential for the clearance of apoptotic cells. Recently we have shown that artificial desialylation of viable cell surfaces creates an “eat-me” signal for macrophages (7).

In phagocytosis assays, human macrophages cleared ER-derived scMP (possessing immature ER-related glycoepitopes) significantly faster than the PM-derived ones (possessing PM-related desialylated glycoepitopes) (Fig. 6). This may result in a differential immunological processing of these subcellular particles and their associated antigens, the size of scMP has had a minor effect on their clearance speed (supplemental Fig. S5).

Intriguingly, nucleosomes, a prototypic autoantigen targeted by sera of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), were mainly concentrated in the bMB (Fig. 2D). This is of particular importance since SLE patients have been reported to frequently display a deficient clearance of apoptotic cells (2).

Vaccinia and other viruses have been shown to mimic PM-derived, phosphatidylserine (PS) exposing scMP, utilizing the ability of surrounding cells for macropinocytosis of PS-exposing particles. This pathway augments the infectivity of the viruses, especially that for phagocytes (26, 27).

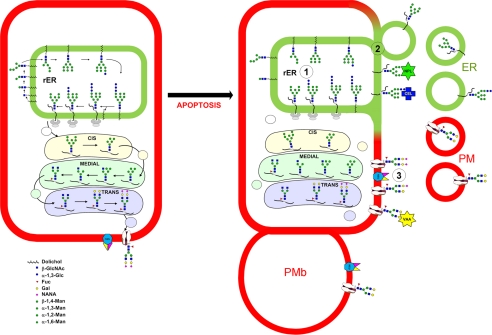

In conclusion, we propose a mechanism including alterations of the glycocalyx during apoptosis and provide evidence that reduced sialylation of cells undergoing apoptosis can be caused by both surface exposure of immature ER-derived GP and surface-bound sialidase activity cleaving mature GP in situ. Our data indicate that these processes are mutually executed by previously undifferentiated types of apoptotic scMP (Fig. 7). ER-derived scMP are prioritized by macrophages during apoptotic cell clearance. Our data are in a good agreement with previous observation where calreticulin exposed from ER during apoptosis has been found to dictate the immunogenicity of cancer cell death (28).

FIGURE 7.

The dual pathway model for altered N-glycan exposure during late apoptosis and formation of two distinct types of scMP (1). Conventional de novo glycan synthesis is not active during apoptosis (2). ER membranes with immature glycans are exposed on the cell surface and in ER-derived scMP (3). Apoptosis is accompanied by a caspase-dependent activation of surface sialidase(s) leading to desialylation of pre-existing glycoepitopes on the cells surfaces and on PM-derived scMP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. U. Engel and Dr. C. Ackermann for excellent technical support.

This work was supported by German-Ukrainian Grant UKR08/035 (to R. B. and M. H.), Grants from NASU, WUBMRC, and the President of Ukraine (to R. B.), by an intramural grant ELAN M3–09.03.18.1 (to L. E. M.), by the DFG (GRK-SFB643), and the K&R Wucherpfennigstiftung (to M. H.). Confocal microscopy was done at the Nikon Imaging Center at the University of Heidelberg.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- scMP

- subcellular membranous particle

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- GP

- glycoprotein

- PMN

- polymorpho-nuclear leukocytes

- PM

- plasma membrane

- RBC

- red blood cells

- bMB

- big membranous blebs

- PBMC

- peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

REFERENCES

- 1. Casciola-Rosen L. A., Anhalt G., Rosen A. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 179, 1317–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Muñoz L. E., Lauber K., Schiller M., Manfredi A. A., Herrmann M. (2010) Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 6, 280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sancho D., Joffre O. P., Keller A. M., Rogers N. C., Martínez D., Hernanz-Falcón P., Rosewell I., Reis E., Sousa C. (2009) Nature 458, 899–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Voll R. E., Herrmann M., Roth E. A., Stach C., Kalden J. R., Girkontaite I. (1997) Nature 390, 350–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ravichandran K. S. (2010) J. Exp. Med. 207, 1807–1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bilyy R., Stoika R. (2007) Autoimmunity 40, 249–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meesmann H. M., Fehr E. M., Kierschke S., Herrmann M., Bilyy R., Heyder P., Blank N., Krienke S., Lorenz H. M., Schiller M. (2010) J. Cell Sci. 123, 3347–3356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bilyy R. O., Stoika R. S. (2003) Cytometry A 56, 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Franz S., Frey B., Sheriff A., Gaipl U. S., Beer A., Voll R. E., Kalden J. R., Herrmann M. (2006) Cytometry A 69, 230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Franz S., Herrmann K., Führnrohr B., Sheriff A., Frey B., Gaipl U. S., Voll R. E., Kalden J. R., Jäck H. M., Herrmann M. (2007) Cell Death. Differ. 14, 733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuno A., Uchiyama N., Koseki-Kuno S., Ebe Y., Takashima S., Yamada M., Hirabayashi J. (2005) Nat. Methods 2, 851–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Warner T. G., O'Brien J. S. (1979) Biochemistry 18, 2783–2787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomin A., Shkandina T., Bilyy R. (2011) Proc. SPIE 8087, 808769 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakano V., Fontes Piazza R. M., Avila-Campos M. J. (2006) Anaerobe 12, 238–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Farrell P. H. (1975) J. Biol. Chem. 250, 4007–4021 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Helenius A., Aebi M. (2001) Science 291, 2364–2369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keller P., Toomre D., Díaz E., White J., Simons K. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 140–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Azuma Y., Sato H., Higai K., Matsumoto K. (2007) Biol. Pharm Bull 30, 1680–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seyrantepe V., Iannello A., Liang F., Kanshin E., Jayanth P., Samarani S., Szewczuk M. R., Ahmad A., Pshezhetsky A. V. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 206–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elliott M. R., Ravichandran K. S. (2010) J. Cell Biol. 189, 1059–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Friggeri A., Banerjee S., Biswas S., de Freitas A., Liu G., Bierhaus A., Abraham E. (2011) J. Immunol. 186, 6191–6198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elliott M. R., Chekeni F. B., Trampont P. C., Lazarowski E. R., Kadl A., Walk S. F., Park D., Woodson R. I., Ostankovich M., Sharma P., Lysiak J. J., Harden T. K., Leitinger N., Ravichandran K. S. (2009) Nature 461, 282–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lauber K., Bohn E., Kröber S. M., Xiao Y. J., Blumenthal S. G., Lindemann R. K., Marini P., Wiedig C., Zobywalski A., Baksh S., Xu Y., Autenrieth I. B., Schulze-Osthoff K., Belka C., Stuhler G., Wesselborg S. (2003) Cell 113, 717–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Savill J. S., Henson P. M., Haslett C. (1989) J. Clin. Investig. 84, 1518–1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Savill J., Fadok V., Henson P., Haslett C. (1993) Immunol. Today 14, 131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mercer J., Helenius A. (2008) Science 320, 531–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mercer J., Helenius A. (2009) Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 510–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Obeid M., Tesniere A., Ghiringhelli F., Fimia G. M., Apetoh L., Perfettini J. L., Castedo M., Mignot G., Panaretakis T., Casares N., Métivier D., Larochette N., van Endert P., Ciccosanti F., Piacentini M., Zitvogel L., Kroemer G. (2007) Nat. Med. 13, 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.