Background: Nitrogen monoxide (NO) can target intracellular iron pools, leading to dinitrosyl iron complexes (DNICs).

Results: NO storage and transport are mediated by glutathione S-transferase P1-1 (GST P1-1) and multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1), respectively.

Conclusion: GST P1-1 and MRP1 form an integrated detoxification unit regulating storage and transport of DNICs.

Significance: These results have broad implications for understanding the transport, storage, and signaling roles of NO.

Keywords: Iron, Iron Metabolism, Metals, Protein Metal Ion Interaction, Transport Metals, Iron, Iron Metabolism, Metals, Protein Metal Iron Interaction, Transport Metals

Abstract

Nitrogen monoxide (NO) plays a role in the cytotoxic mechanisms of activated macrophages against tumor cells by inducing iron release. We showed that NO-mediated iron efflux from cells required glutathione (GSH) (Watts, R. N., and Richardson, D. R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4724–4732) and that the GSH-conjugate transporter, multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1), mediates this release potentially as a dinitrosyl-dithiol iron complex (DNIC; Watts, R. N., Hawkins, C., Ponka, P., and Richardson, D. R. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7670–7675). Recently, glutathione S-transferase P1-1 (GST P1-1) was shown to bind DNICs as dinitrosyl-diglutathionyl iron complexes. Considering this and that GSTs and MRP1 form an integrated detoxification unit with chemotherapeutics, we assessed whether these proteins coordinately regulate storage and transport of DNICs as long lived NO intermediates. Cells transfected with GSTP1 (but not GSTA1 or GSTM1) significantly decreased NO-mediated 59Fe release from cells. This NO-mediated 59Fe efflux and the effect of GST P1-1 on preventing this were observed with NO-generating agents and also in cells transfected with inducible nitric oxide synthase. Notably, 59Fe accumulated in cells within GST P1-1-containing fractions, indicating an alteration in intracellular 59Fe distribution. Furthermore, electron paramagnetic resonance studies showed that MCF7-VP cells transfected with GSTP1 contain significantly greater levels of a unique DNIC signal. These investigations indicate that GST P1-1 acts to sequester NO as DNICs, reducing their transport out of the cell by MRP1. Cell proliferation studies demonstrated the importance of the combined effect of GST P1-1 and MRP1 in protecting cells from the cytotoxic effects of NO. Thus, the DNIC storage function of GST P1-1 and ability of MRP1 to efflux DNICs are vital in protection against NO cytotoxicity.

Introduction

Nitrogen monoxide (NO) is a short lived messenger molecule that plays multiple physiological roles (1). Many of these actions are mediated by NO binding iron in the heme group of soluble guanylate cyclase (1). The importance of iron in mediating the functions of NO is also apparent when examining its cytotoxic effects. The cytotoxic functions of NO are observed when it is produced in large amounts by activated macrophages (MØs)5 against pathogens and tumor cells (2). These effects are explained by the reactivity of NO with iron in iron-sulfur clusters, e.g. in the electron transport chain and other pools (1, 3). The high affinity of NO for Fe(II) results in the interaction of NO with iron-sulfur clusters in proteins. which leads to their degradation and the formation of dinitrosyl-dithiol iron complexes (DNICs) (4, 5). Landmark studies by Hibbs et al. (2) demonstrated that co-cultivation of tumor target cells with MØs results in the loss of cellular iron. Further, it is known that NO induces the formation of DNICs with the formula Fe(RS)2(NO)2 (6) in MØs and tumor cells (7, 8). These can be readily detected by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) and give a unique signal of g = 2.04 (8). Intriguingly, it has been recently suggested that DNICs are the most abundant cellular adducts after exposure to NO (9).

In previous studies, we examined the effect of NO on the iron metabolism of neoplastic cells and showed that it led to the efflux of intracellular iron (10, 11). Subsequently, we discovered that the glutathione (GSH) transporter, multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1), mediates NO-stimulated iron and GSH efflux from cells and that this process could be inhibited by l-buthionine-(S,R)-sulfoximine (BSO) (12), an inhibitor of GSH synthesis (13). Several recent investigations have suggested that DNICs such as dinitrosyl-diglutathionyl iron complexes can bind to glutathione S-transferase (GST) isoenzymes with high affinity (Kd = 10−7-10−10 m) (14, 15). In fact, a crystal structure of the DNIC-GST P1-1 complex (PDB ID: IZGN) revealed that Tyr-7 in the active site of the enzyme coordinates to iron in the DNIC, displacing one GSH ligand (14). Previous studies with toxic exogenous (e.g. anticancer drugs) and endogenous agents have shown that GST isoenzymes form an integrated detoxification unit with MRP1 that eliminates GSH conjugates (16, 17).

Considering the coordinated role of GSTs and MRP1 in detoxification processes (16–18) and our studies showing that MRP1 is involved in NO-mediated iron and GSH efflux from cells (12), we have for the first time examined the hypothesis that GST isoenzymes α (GST A1-1), μ (GST M1-1), and π (GST P1-1) and MRP1 act as coordinate partners involved in the storage and transport of DNICs, respectively. In the current study, we show that GST P1-1, but not GST A1-1 or GST M1-1, decreased NO-mediated 59Fe release from cells via MRP1, demonstrating a relationship between the proteins in terms of NO storage and transport and the role of DNICs in these processes. These results are important for understanding the intracellular trafficking of NO, which has broad consequences for interpreting the diverse biological functions of this molecule.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tissue Culture

Murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from MRP1 or GSTP1 wild-type or knock-out (KO) mice were gifts from Drs. P. Borst (NKI-AVL, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and K. Tew (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC), respectively. MCF7-WT (WT) and MCF7-VP (VP) cells transfected with GSTA1, GSTM1, or GSTP1 or their empty vectors were described previously by us (16, 18). The HaCaT keratinocyte cell type was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Protein Labeling

Apo-transferrin (Apo-Tf; Sigma-Aldrich) was labeled with 59Fe (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) to generate diferric 59Fe-Tf using established methods (12). 59Fe was monitored using a γ-counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed (19) using antibodies against GST A1-1, M1-1, and P1-1 (Calbiochem; 1:1000) and MRP1 (Alexis, San Diego, CA; 1:500).

Efflux of 59Fe, General Protocol

Standard methods were used to examine the effect of NO and other agents on 59Fe efflux from cells (10). Cells were labeled with 59Fe-Tf ([Tf] = 0.75 μm) for 3 h at 37 °C. The cells were then washed four times on ice and reincubated at 37 °C in treatment medium as indicated. The supernatants and cell pellets were collected for 59Fe measurement using the γ-counter above (10).

Efflux of 59Fe from MEFs

Cells were prelabeled for 24 h with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm), washed, and then preincubated for 30 min at 37 °C with medium containing the MRP1 inhibitor, MK571 (20 μm) (12). The cells were then reincubated for 6 h at 37 °C with MK571 (20 μm) in the presence or absence of the NO generator, S-nitroso-glutathione (GSNO; 0.5 mm). For concentration dependence studies, cells were prelabeled for 24 h at 37 °C with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm), washed, and then incubated for 6 h at 37 °C with medium containing 0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.5 mm of the well characterized NO generators, GSNO or spermine NONOate (SperNO; both from Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). As relevant negative controls, cells were also incubated with the same concentrations of the agents without the NO group, namely GSH and spermine (both from Sigma-Aldrich).

Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS) Transient Transfection

The iNOS plasmid was a kind gift from Dr. Helen McCarthy (Queens University, Belfast, Ireland). MRP1 KO- and WT-MEFs or MCF7-VP cells stably transfected with GSTP1 or the empty vector were transiently transfected with the iNOS plasmid or this plasmid without the iNOS insert using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen) using the manufacturer's protocol. Then 24 h after transfection, cells were prelabeled for 24 h at 37 °C with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) and washed four times on ice, and the cells then reincubated for 24 h at 37 °C with control medium. Efflux of 59Fe and nitrite (see below) was then determined.

Determination of Nitrite Concentration

Accumulation of nitrite in culture medium was used as an indicator of iNOS activity in cells. Nitrite concentration in the medium was measured using the Griess reagent via standard procedures (10, 11).

siRNA Study

siRNAs specific for GSTP1 (Ambion, Austin, TX) and the scrambled control siRNA (Ambion) were used for gene knockdown studies in HaCaT cells. Cells were transiently transfected with siRNA (100 nm) using LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen). Then 72 h after transfection, the cells were assayed for 59Fe efflux and GST P1-1 levels using Western blot.

Determination of Intracellular 59Fe Distribution

Cells were incubated with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) and GSNO (0.5 mm) for 3 h at 37 °C. The cells were washed four times on ice and lysed. The lysates were centrifuged at 16,500 × g for 45 min at 4 °C, and the cytosolic fraction was analyzed to assess intracellular 59Fe distribution by native fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) (19).

Cell Proliferation

Proliferation was assessed by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay and validated by viable cell counts (12).

EPR Spectroscopy

This technique was performed using a Bruker EMX spectrometer with 100-kHz modulation, as described (12).

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. (number of experiments). Data were compared using Student's t test. Results were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Statistical analysis of EPR studies was done by repeated measures one-way analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

RESULTS

MRP1 Mediates NO-induced 59Fe Efflux from Cells

Our previous studies demonstrated that hyper-expression of MRP1 in VP cells led to a marked increase in NO-mediated efflux of 59Fe and GSH when compared with their WT counterparts (12). Considering the potential for GST isoenzymes and MRP1 to form an integrated system for DNIC transport, further studies were performed to investigate the role of MRP1 in NO-mediated 59Fe transport using MEFs from wild-type mice (WT-MEFs, which express MRP1) and MRP1 knock-out mice (MRP1 KO-MEFs). Cells were labeled for 24 h at 37 °C with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm), washed four times on ice, and then incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with either control medium or medium containing the well known inhibitor of MRP1, MK571 (20 μm (12, 20)). The cells were then reincubated for 6 h at 37 °C with the NO generator, GSNO (0.5 mm), or control media, in the presence or absence of MK571 (20 μm), and cellular 59Fe release was then examined (10, 12).

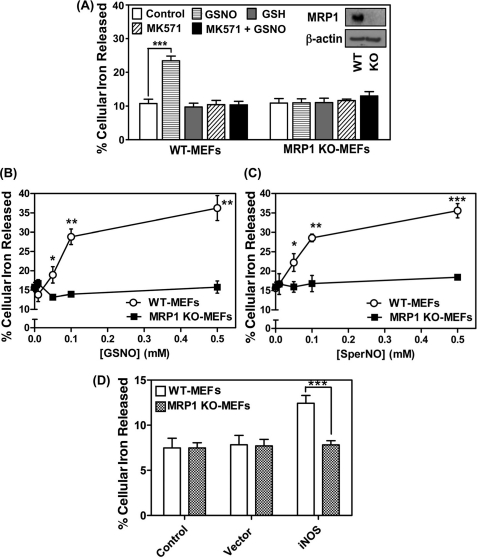

Incubation with GSNO (0.5 mm) induced a marked and significant (p < 0.001) 2-fold increase in 59Fe release from WT-MEFs, but had no significant (p > 0.05) effect on 59Fe release from MRP1 KO-MEFs (Fig. 1A). Importantly, MK571 totally prevented GSNO-induced 59Fe efflux from WT-MEFs and had no significant effect on 59Fe release from MRP1 KO-MEFs. These results confirmed the role of MRP1 in NO-mediated 59Fe efflux from cells (12). In these studies, GSH acted as a negative control for GSNO as it does not contain the NO group and had no effect on 59Fe mobilization (Fig. 1A). Hence, consistent with our previous study (12), these results showed that MRP1 was crucial for NO-mediated 59Fe efflux.

FIGURE 1.

MRP1 mediates NO-stimulated 59Fe release. A, WT- and MRP1 KO-MEFs were labeled with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) for 24 h at 37 °C, washed on ice, and then incubated with control medium with or without MK571 (20 μm) for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were then reincubated with control medium containing either GSNO (0.5 mm) or GSH (0.5 mm) with or without MK571 (20 μm) for 6 h at 37 °C. The inset shows MRP1 protein expression in WT- and MRP1 KO-MEFs (typical of 3 experiments). B and C, WT- and MRP1 KO-MEFs were labeled with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) for 24 h at 37 °C, washed on ice, and then incubated with control medium containing either GSNO (0.01, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.5 mm) (B) or SperNONOate (0.01, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.5 mm) (C) for 6 h at 37 °C. D, WT- and MRP1 KO-MEFs cells were transfected with either iNOS or the relevant empty vector, labeled with 59Fe-Tf as described for B and C, and then reincubated with control medium for 24 h at 37 °C. The activity of iNOS was assessed by nitrite accumulation in the incubation medium (see “Results”). Results are mean ± S.D. (3 experiments). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Low Concentrations of Different NO generators Induce 59Fe Efflux, but Only from Cells Expressing MRP1

Studies were then performed to compare the effect of a concentration range (0.01–0.5 mm) of two NO-generating agents, namely GSNO (Fig. 1B) and SperNO (Fig. 1C), on 59Fe release from MRP1 KO-MEFs relative to WT-MEFs. Two chemically different NO generators were compared to examine the possibility that the effect observed was only relevant for NO generated by GSNO.

In these experiments, cells were labeled with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) for 24 h at 37 °C, washed, and then reincubated for 6 h at 37 °C in the presence of control medium or the NO generators (0.01–0.5 mm). As observed in Fig. 1A, NO-mediated 59Fe release was only identified in WT cells, there being a significant (p < 0.05) increase in 59Fe release at 0.05 mm with either agent relative to MRP1 KO-MEFs (Fig. 1, B and C). Efflux of 59Fe from WT-MEFs continued to significantly increase relative to MRP1 KO-MEFs as a function of concentration for both NO generators up to 0.5 mm, where the release reached 35–36% of the total cellular 59Fe. In contrast, GSNO or SperNO did not have any effect on 59Fe release from MRP1 KO-MEFs relative to the control medium (Fig. 1, B and C). Incubation with the relative control agents without the NO group, namely GSH or spermine, led to no effect on 59Fe efflux relative to the control (data not shown), as observed in our previous studies (10–12). These results demonstrated that even very low concentrations of the NO donor markedly increased 59Fe efflux from cells that express MRP1 relative to those that do not. Furthermore, considering that GSNO is a physiologically relevant NO donor (21, 22) and that the nitrite levels generated by this agent (10) are similar to, or much less, than those identified in vivo (23), it is apparent the NO levels used herein are within the physiological range (1).

iNOS Only Increases 59Fe Release from Cells Expressing MRP1

Considering the NO-mediated 59Fe release from cells described above using exogenous NO-generating agents, the effect of intracellular NO generation via iNOS was then assessed. The MRP1 KO- and WT-MEFs were transfected with iNOS or the relevant empty vector, and the cells were prelabeled with 59Fe-Tf as described for Fig. 1, B and C, and reincubated in the presence of control medium for 24 h at 37 °C. Under these conditions, iNOS induced a significant (p < 0.001) increase in 59Fe release from WT-MEFs, whereas no significant (p > 0.05) alteration in 59Fe release from MRP1 KO-MEFs occurred relative to empty vector-transfected cells (Fig. 1D). Nitric oxide generation was monitored by the detection of nitrite, which was 8-fold greater in cells transfected with iNOS (8.0 ± 0.4 μm, n = 3) relative to those transfected with the empty vector (1.0 ± 0.1 μm, n = 3). Collectively, these data demonstrated the importance of MRP1 in NO-mediated 59Fe efflux.

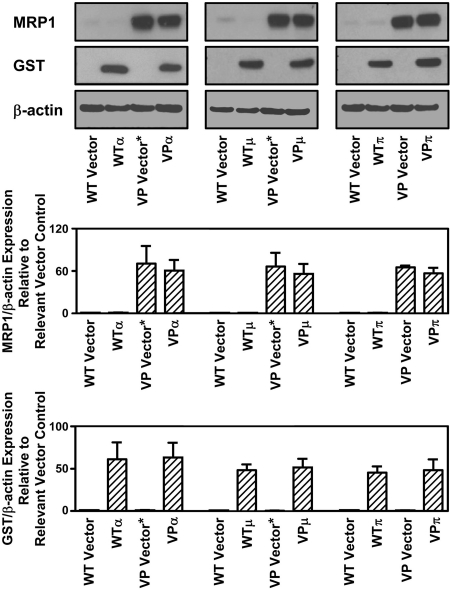

MCF7-WT and MCF7-VP Cells Stably Transfected with GSTs as Models to Test Interaction between MRP1 and GSTs

To initially test the role of MRP1 and GSTs in NO and iron metabolism, a cell model that hyper-expressed one or both of these proteins was required. Based on our previous use of the VP and WT cell types to assess the role of MRP1 in NO-mediated 59Fe release (12), we used these two cell types stably transfected with three major classes of human cytosolic GST isoenzymes (α, μ, and π), namely: GST A1-1, GST M1-1, or GST P1-1 (Fig. 2) (16). In this study, these transfected cell lines are designated as: VPα, VPμ, VPπ, WTα, WTμ, and WTπ, respectively. The vector used to transfect cells with GSTP1 (encoding GST P1-1) is denoted as “VP Vector,” whereas that used to transfect GSTA1 (encoding GST A1-1) or GSTM1 (encoding GST M1-1) is denoted as “VP Vector*.” In all studies, the cell type transfected with the relevant empty vector was used as the control.

FIGURE 2.

Western blot analysis demonstrating MRP1 expression in MCF7-VP and MCF7-WT cells as well as the pronounced protein expression of GST P1-1, GST A1-1, or GST M1-1 in cells transfected with GSTP1, GSTA1, or GSTM1, respectively, relative to cells transfected with the appropriate empty vectors alone. Photographs of blots are typical of 3 experiments, and densitometry is mean ± S.D. (3 experiments).

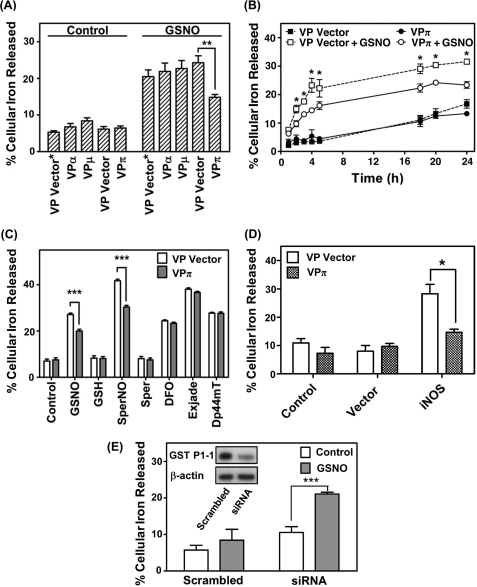

GST P1-1 Inhibits 59Fe Release from Cells Hyper-expressing MRP1

Although GSTs bind DNICs (14, 15), their role in iron and NO metabolism in intact mammalian cells has never been assessed, particularly in the context of their relationship with MRP1. Considering that GSTs bind DNICs (14, 15), MCF7-VP cells transfected with GSTA1, GSTM1, or GSTP1 (VPα, VPμ, or VPπ) and their relevant controls (VP Vector or VP Vector*) (Fig. 2) were examined in terms of cellular 59Fe mobilization with or without an NO generator (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Only GST P1-1, but not GST A1-1 or M1-1, significantly inhibits NO-mediated 59Fe release from MRP1 hyper-expressing VP cells. A, cells were labeled with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) for 3 h at 37 °C, washed, and then reincubated for 3 h at 37 °C with or without GSNO (0.5 mm) at 37 °C. B, cells were labeled and washed as in A and then reincubated with or without GSNO (0.5 mm) for up to 24 h at 37 °C. Significance values compare VPπ and VP Vector cells treated with GSNO at the relevant time points. C, cells were labeled and washed as in A and then reincubated with control medium or medium containing GSNO, SperNO, GSH, or spermine (Sper) (all at 0.5 mm) or the iron chelators desferrioxamine (DFO), Exjade®, or di-2-pyridylketone 4,4-dimethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (Dp44mT) (all at 25 μm) for 3 h at 37 °C. D, VP Vector and VPπ cells transfected with either iNOS or vector were labeled with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) for 24 h at 37 °C, washed on ice, and then incubated with control medium for 24 h at 37 °C. Activity of iNOS was assessed by nitrite accumulation in the incubation medium (see “Results”). E, HaCaT cells treated with either si-GSTP1 (siRNA) or scrambled siRNA (Scrambled) were labeled, washed, and treated as in A. Western analysis was then done to assess GST P1-1 expression (see inset that is typical of 3 experiments). Results are mean ± S.D. (3 experiments). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Reincubation of the various 59Fe-labeled VP cell types with control media alone (without NO) did not result in any significant (p > 0.05) alteration in 59Fe release from all cell lines relative to the VP Vector or VP Vector* controls, with 5–8% of 59Fe being released (Fig. 3A). In contrast, GSNO (0.5 mm) induced a marked and significant (p < 0.001) increase in 59Fe release from all cell types relative to cells incubated with control media (Fig. 3A). The addition of GSNO had no effect on cell viability over 3 h as judged by phase contrast microscopy and Trypan blue staining, as shown in our previous investigations (11). However, VPπ cells showed a significant (p < 0.01) decrease in GSNO-mediated 59Fe efflux relative to VP Vector cells, whereas no effect on 59Fe efflux was observed with VPα or VPμ cells relative to the VP Vector* (Fig. 3A).

The efflux of 59Fe from VPπ cells in the presence of elevated GST P1-1 was then examined in time course studies with cells being labeled for 3 h at 37 °C with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) followed by washing and reincubation with or without GSNO (0.5 mm) for 1–24 h (Fig. 3B). Again, VPπ cells significantly (p < 0.05) reduced GSNO-mediated 59Fe release between 2 and 24 h when compared with VP Vector cells (Fig. 3B). There was no significant effect of GST P1-1 on 59Fe release from VPπ cells incubated with control medium in the absence of exogenous NO for all incubation times relative to VP Vector cells (Fig. 3B). This indicates that the effect of GST P1-1 on cellular 59Fe release is restricted to NO-mediated iron efflux.

To examine whether the effect of GST P1-1 on 59Fe mobilization could potentially be due to decreased generalized membrane permeability of the VPπ cells relative to VP Vector cells, the cells were labeled with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) for 3 h at 37 °C, washed, and then reincubated with the structurally distinct NO generators (GSNO or SperNO; 0.5 mm), their control compounds (GSH or spermine, respectively), or a variety of iron chelators at 25 μm (i.e. desferrioxamine, Exjade®, or di-2-pyridylketone 4,4-dimethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (24) (Fig. 3C). Both NO-generating agents and the iron chelators significantly (p < 0.001) increased cellular 59Fe efflux relative to control medium, whereas GSH and spermine had no significant effect. Of the five agents that mobilized cellular 59Fe, only GSNO and SperNO led to significant (p < 0.001) 59Fe retention in VPπ cells relative to VP Vector cells (Fig. 3C). This indicates that the effect of GST P1-1 at inhibiting 59Fe release was not due to a general difference in membrane permeability between the cell types, but was related to the interaction between NO and iron. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of GST P1-1 at preventing NO-mediated 59Fe mobilization could not be observed using diverse chelators that form iron complexes that differ greatly in structure from DNICs (24). This can be explained by the specificity of DNIC binding to the stereochemically defined site within GST P1-1 (14).

GST P1-1 Expression in VPπ Cells Prevents 59Fe Efflux Mediated by Transient Transfection of iNOS

Considering that NO-mediated 59Fe efflux was only decreased in cells transfected with GST P1-1 (i.e. VPπ cells) after incubation with exogenous NO generators (Fig. 3A), studies then progressed to assess whether a similar effect could be observed when these cells were transfected with iNOS. In these experiments, VP and VPπ cells were transfected with iNOS or the empty vector alone, and the cells were then reincubated with medium alone for 24 h at 37 °C (Fig. 3D). Examining VP or VPπ control cells (not transfected with iNOS or its relative empty vector) or those transfected with the empty vector alone, there was no significant difference in 59Fe mobilization between these cell types, which was ∼7–11% of the total cell 59Fe. However, transfection of VP Vector cells with iNOS significantly (p < 0.01) increased 59Fe release to 29 ± 2% of the total relative to these cells transfected with the empty vector (Fig. 3D). In contrast, transfection of VPπ cells with iNOS led to 14 ± 1% of total cell 59Fe being released, which was significantly (p < 0.05) less than that observed when VP Vector cells were transfected with the same plasmid. Again, measurement of nitrite levels was used to monitor the generation of NO by iNOS. In these experiments, nitrite was present at levels 7-fold greater (7.0 ± 1.0 μm, n = 3) in cells transfected with iNOS relative to the empty vector (1.0 ± 0.1 μm, n = 3). In summary, the results in Fig. 3, A–D, indicate that GST P1-1 prevents 59Fe efflux mediated by exogenous NO donors or intracellular iNOS.

Knockdown of GST P1-1 in HaCaT Keratinocytes Increases GSNO-mediated 59Fe Efflux

To examine NO-mediated 59Fe release from cells expressing endogenous GST P1-1, HaCaT cells were used, which express high levels of GST P1-1 (25) and MRP1 (26). We transiently transfected siRNA specific for GSTP1 relative to a scrambled siRNA control to assess the effect of decreased expression of this protein on GSNO-mediated 59Fe release (Fig. 3E). A marked and significant (p < 0.001) decrease in GST P1-1 expression in siRNA-treated cells relative to control (scrambled siRNA) treated cells (Fig. 3E, inset) led to a significant (p < 0.001) increase in GSNO-mediated 59Fe mobilization (Fig. 3E). These results support the studies above showing that GST P1-1 prevents NO-mediated 59Fe efflux from cells.

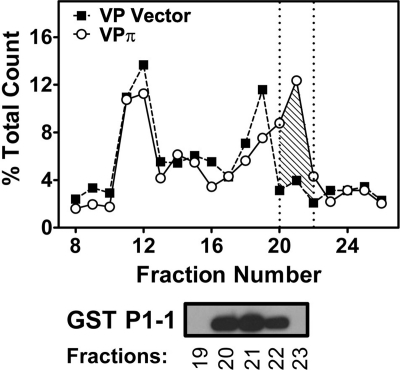

Non-denaturing FPLC Demonstrates 59Fe Accumulation in Cell Fractions Containing GST P1-1

Collectively, the studies above demonstrated that GST P1-1 prevented 59Fe release from cells, and this was probably due to an intracellular accumulation of 59Fe as the DNIC-GST P1-1 complex (14). To examine this further, the intracellular distribution of 59Fe was assessed using non-denaturing FPLC (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). VPπ, VPα, or VPμ cells and their relevant vector controls were labeled with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) in the presence of GSNO (0.5 mm) for 3 h at 37 °C prior to analysis by FPLC. Significantly (p < 0.001) increased intracellular 59Fe was found in fractions 20–22 (Fig. 4, shaded area), which contained GST P1-1 in VPπ cells relative to VP Vector cells. This suggested that the altered cellular 59Fe distribution was due to the formation of a 59Fe-DNIC-GST P1-1 complex (14), and this conclusion was supported by the functional studies in Fig. 3.

FIGURE 4.

Increased intracellular 59Fe accumulation is identified in a peak that contains GST P1-1 in VPπ cells relative to VP Vector cells after fractionation of the cytosol using non-denaturing FPLC. VP cells (transfected with vector alone or GSTP1) were incubated with 59Fe-Tf (0.75 μm) for 3 h at 37 °C with GSNO (0.5 mm). The cells were then washed and lysed, and the cytosolic fraction was analyzed by FPLC. The fractions were then assessed by Western blot, and GST P1-1 expression was observed in fractions 20, 21, and 22 only. Results are typical of 3 experiments.

The intracellular 59Fe distribution in VPα and VPμ cells relative to VP Vector* cells was then assessed (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). The distribution of 59Fe in VPα and VPμ cells was different from that found in VPπ cells, probably because these are different clones. However, although GST A1-1 and GST M1-1 were also detected by Western blot in fractions 20–22, there was no increase in 59Fe content above that found for VP Vector* cells in these fractions (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). Collectively, these native FPLC results confirmed that GST P1-1, but not GST A1-1 or M1-1, resulted in increased intracellular 59Fe retention by the protein.

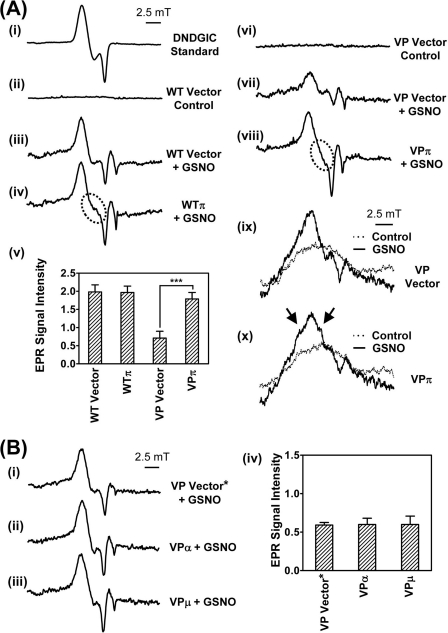

EPR at 77 K Demonstrates Formation of a DNIC-GST P1-1 Complex in MCF7-WT Cells

To further elucidate the altered 59Fe distribution in NO-treated VPπ cells observed in Fig. 4, EPR (7, 12) at 77 K was used to assess the formation of cellular DNICs after exposure to GSNO (0.5 mm) for 3 h at 37 °C. As a control, we first examined the EPR signal of a synthetically prepared (15) low Mr DNIC, containing GSH (dinitrosyl-diglutathionyl iron complex), which gives the characteristic spectrum of this complex with g = 2.04 (15, 27) (Fig. 5A, panel i). Incubation of WT cells transfected with the empty vector alone (WT Vector) for 3 h at 37 °C with control medium gave no EPR signal (Fig. 5A, panel ii). In contrast, incubation of WT Vector cells with GSNO gave a clear EPR signal (Fig. 5A, panel iii) that was similar to the synthetic DNIC standard (Fig. 5A, panel i). Hence, these data indicate DNIC formation in cells incubated with an exogenous NO generator (7, 12). As expected, solutions of GSNO or GSH alone (0.5 mm) in the absence of cells gave no significant EPR signals (Fig. S2A, panels i and ii). Interestingly, in WT cells transfected with GSTP1 (WTπ) and incubated with GSNO, a different EPR line shape was observed (Fig. 5A, panel iv, circled area) when compared with WT Vector cells (Fig. 5A, panel iii). These results suggest changes in the coordination sphere of the complex due to the binding of different ligands (6, 12). Thus, these results are consistent with the formation of a chemically distinct complex in the presence of GST P1-1.

FIGURE 5.

Transfection of WT or VP cells with GSTP1, but not GSTA1 or GSTM1, resulted in a unique EPR signal after incubation with GSNO (0.5 mm) for 3 h at 37 °C. A, panels i–iv, low temperature (77 K) EPR spectra of a synthetic dinitrosyl diglutathionyl iron complex (DNDGIC; 0.5 mm) (panel i); WT Vector cells (1010 cells) incubated with either control medium (panel ii) or GSNO (0.5 mm) (panel iii); and WTπ cells after incubation with GSNO (0.5 mm) (panel iv). Panel v, quantification of EPR signals from panels iii and iv and from panels vii and viii. EPR signal intensity is represented as normalized peak height in arbitrary units. Results are mean ± S.D. (3–5 experiments), ***, p < 0.001. Panels vi and vii, low temperature (77 K) EPR spectra of VP Vector cells incubated with either control medium (panel vi) or GSNO (0.5 mm) (panel vii). Panel viii, VPπ cells after incubation with GSNO (0.5 mm). Panels ix and x, room temperature (293 K) EPR spectra of VP Vector (panel ix) or VPπ cells (panel x) after incubation with GSNO (0.5 mm) or control medium for 3 h at 37 °C. Arrows highlight the additional features resolved in the VPπ cells, consistent with the formation of different DNICs when compared with VP Vector cells. B, panels i–iii, low temperature (77 K) EPR spectra of VP Vector* (panel i), VPα (panel ii), or VPμ (panel iii) cells incubated with GSNO (0.5 mm) for 3 h at 37 °C. Panel iv, quantification of EPR signals from panels i–iii. EPR signal intensity is represented as normalized peak height in arbitrary units. Results are typical scans of 3–5 experiments, and the quantification represents mean ± S.D. (3–5 experiments).

Over 3 experiments, there was no significant difference in the intensity of the EPR signal between WT Vector or WTπ cells incubated with GSNO (Fig. 5A, panel v). In addition, no EPR signal was obtained when WTπ cells were incubated with control medium alone (supplemental Fig. S2B, panel i).

EPR at 77 K Shows That GST P1-1 Expression Increases Intensity of the EPR DNIC Signal in VP Cells

Studies then assessed EPR spectra of VP cells at 77 K (Fig. 5A, panels vi–viii) for comparison with the spectra of WT cells (Fig. 5A, panels ii–iv). As found in WT cells (Fig. 5A, panel ii), incubation of VP Vector cells in control medium gave no EPR signal at 77 K (Fig. 5A, panel vi), and this was also observed with VPπ cells incubated in control medium (supplemental Fig. S2B, panel ii).

However, incubation of VP Vector cells with GSNO led to an EPR signal (Fig. 5A, panel vii) that was similar in line shape, but significantly less (p < 0.001) intense, than that in WT Vector cells (Fig. 5A, panel iii). The lower intensity EPR signal in the VP Vector cells relative to WT Vector cells incubated with GSNO could be explained by the hyper-expression of MRP1 in VP cells (Fig. 2). This leads to marked NO-induced iron and GSH efflux from the cell via MRP1 (12), and thus, a less intense DNIC EPR signal. Comparison of VP Vector cells (Fig. 5A, panel vii) and VPπ cells (Fig. 5A, panel viii) in the presence of GSNO demonstrated: 1) a difference in the shape of the EPR signal and 2) a marked and significant (p < 0.001) increase in the intensity of the EPR signal in the VPπ cells relative to the VP Vector cells (Fig. 5A, panel v). Irrespective of whether either GSNO or SperNO was used as the NO generator, the same EPR spectrum was observed in VPπ cells (supplemental Fig. S3). This indicates that the spectra obtained were not dependent on the NO source. Collectively, these observations demonstrated greater accumulation of the DNIC in VPπ cells and the direct binding of DNICs by GST P1-1 (14).

It is notable that no difference in intensity of the DNIC EPR signal was found between WT Vector (Fig. 5A, panel iii) and WTπ (Fig. 5A, panel iv) cells in the presence of GSNO, whereas a significant (p < 0.001) difference was observed comparing VP Vector (Fig. 5A, panel vii) and VPπ (Fig. 5A, panel viii) cells treated similarly. This disparity may relate to the marked MRP1 expression in VP cells (Fig. 2), which actively transports iron and GSH out of the cell probably as DNICs (12), making the VPπ DNIC binding and accumulation by GST P1-1 obvious. Indeed, the efficient efflux of the DNICs by MRP1 out of VPπ cells may limit NO binding to other iron-containing molecules (e.g. iron-sulfur clusters that are known to form DNICs (1, 28, 29)), preventing their generation and removing this “background DNIC signal.” In contrast, in WT cells, MRP1 is not present at significant levels (Fig. 2) to efficiently “pump out” DNICs. Hence, the increased binding of DNICs by GST P1-1 in WT cells may be obscured via the generation of DNICs with other iron-containing molecules that scavenge excess NO.

The results above using EPR are in very good agreement with our functional data in VPπ cells, where: 1) NO-mediated 59Fe release from VPπ cells was significantly lower than from the VP Vector cells (Fig. 3, A–D), demonstrating binding of the DNIC by GST P1-1; and 2) intracellular 59Fe distribution studies showed that 59Fe accumulated in the GST P1-1-containing fractions (Fig. 4).

EPR Spectra at 293 K Demonstrate Formation of a DNIC-GST P1-1 Protein Complex

EPR spectra were then recorded at 293 K (Fig. 5A, panels ix and x) to differentiate between protein-bound and low Mr DNICs (12), which is not possible at 77 K because of the immobilization of the complexes upon freezing. EPR analysis at 293 K revealed low intensity, broad, anisotropic signals with no resolvable fine structure in GSNO (0.5 mm)-treated VP Vector cells (Fig. 5A, panel ix) that were not observed in VP Vector cells incubated with control medium alone (Fig. 5A, panel ix). Importantly, EPR spectra of VPπ cells at 293 K revealed the presence of additional features (Fig. 5A, panel x, marked by arrows) in the signals after incubation with GSNO. These findings were consistent with the formation of a specific DNIC-GST P1-1 protein complex (g = 2.04) (14, 27).

These results at 293 K were consistent with the formation of a specific DNIC-GST P1-1 protein complex (g = 2.04) (14, 27) and support the EPR studies done at 77 K that suggest the formation of a chemically distinct DNIC in the presence of GST P1-1 (Fig. 5A, panel iii, cf. panel iv, and Fig. 5A, panel vii, cf. panel viii). Furthermore, considering these results together with: 1) x-ray crystallography studies that showed that GST P1-1 forms a distinctive DNIC through ligation to Tyr-7 displacing one GSH ligand (14); 2) the significant increase in the EPR signal intensity at 77 K comparing VP cells transfected with GST P1-1 relative to the empty vector (Fig. 5A, panel v); and 3) FPLC experiments that directly demonstrated 59Fe accumulation in cell fractions containing GST P1-1 (Fig. 4), it can be concluded that GST P1-1 acted effectively to bind DNICs.

In further support of the results above, GSTP1 knock-out (GST P1-1 KO) MEFs displayed a marked (p < 0.001) decrease in the EPR-DNIC signal at 77 K (supplemental Fig. S2C, panel iv) relative to WT-MEFs (supplemental Fig. S2C, panel ii), confirming the role of GST P1-1 in DNIC binding (14). Clearly, a weak DNIC EPR signal was still observed in GSTP1 knock-out cells as other molecules apart from GST P1-1 (e.g. iron-sulfur cluster-containing proteins) are also known to form DNICs (1, 28, 29). Of relevance, WT-MEFs and GST P1-1 KO-MEFs incubated with control medium alone did not display a DNIC signal (supplemental Fig. S2C, panels i and ii).

Unlike GST P1-1, GST A1-1 and GST M1-1 Do Not Alter EPR Spectra

Unlike VPπ cells, no alteration in EPR line shape or a significant increase in signal intensity was found at 77 K when comparing VP Vector* cells (Fig. 5B, panel i) with VPα (Fig. 5B, panel ii) or VPμ (Fig. 5B, panel iii) cells after incubation with GSNO (0.5 mm) for 3 h at 37 °C (Fig. 5B, panel iv). This supports our functional studies, where GST A1-1 or M1-1 had no significant effect on cellular 59Fe release (Fig. 3A), nor did these proteins bind intracellular 59Fe, as indicated by native FPLC (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). As found for the VP Vector cell type incubated with control media (Fig. 5A, panel vi), VP Vector* cells treated in the same way gave no EPR signal, and this was also observed for VPα and VPμ cells incubated with control media (supplemental Fig. S2D, panels i–iii).

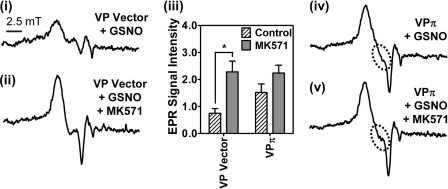

MRP1 Inhibitor, MK571, Increases EPR DNIC Signal in VP Vector Cells

The role of GST P1-1 in preventing NO-mediated 59Fe release via MRP1 (Fig. 3, A–D) was further examined using the MRP1 inhibitor, MK571 (12, 20). Preincubation of VP Vector cells with MK571 for 30 min prior to and during the 3 h at 37 °C incubation with GSNO (0.5 mm) led to a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the EPR signal intensity (cf. Fig. 6, panels i and ii), demonstrating cellular accumulation of DNICs, due to the inhibition of MRP1 transport activity. The addition of MK571 to VPπ cells incubated with GSNO also increased the signal relative to GSNO-treated VPπ cells (cf. Fig. 6, panels iv and v), although this was not a significant increase (Fig. 6, panel iii). This lack of a marked increase in the signal may be attributed to the larger amount of 59Fe-NO already trapped within the cell by GST P1-1, saturating the compartment.

FIGURE 6.

The MRP1 inhibitor, MK571, markedly increases EPR signal intensity in VP Vector cells. Panels i and ii, low temperature (77 K) EPR spectra of VP Vector cells (1010 cells) preincubated with or without MK571 (20 μm) for 30 min at 37 °C followed by incubation for 3 h at 37 °C with either GSNO (0.5 mm) (panel i) or MK571 (20 μm) and GSNO (0.5 mm) (panel ii), respectively. Panel iii, quantification of EPR signals from VP Vector or VPπ cells in the presence or absence of MK571. EPR signal intensity is represented as normalized peak height in arbitrary units. Results are typical scans of 3–5 experiments, and the quantification represents mean ± S.D. (3–5 experiments), *, p < 0.05. Panels iv and v, low temperature (77 K) EPR spectra of VPπ cells (1010 cells) incubated with GSNO (0.5 mm) for 3 h in the presence and absence of MK571 (20 μm). Results are typical from 5 experiments.

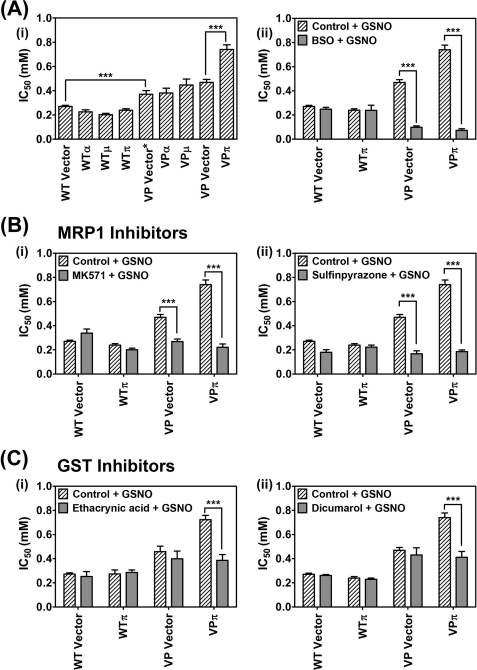

Effect of GSTs on Proliferation of MCF7-WT and -VP Cells in the Presence of NO

The relationship between GST P1-1 and MRP1 in the storage and transport of DNICs may be part of a novel detoxification system, protecting cells from endogenous NO generated by nitric oxide synthase or from exogenous NO generated by MØs (2). Considering this, we assessed the effect of GSNO (0.02–10 mm) over 72 h on proliferation of WT and VP cells transfected with each GST isoform (Fig. 7A, panel i). Transfection of WT cells with GSTA1, GSTM1, or GSTP1 (WTα, WTμ, WTπ cells) had no significant effect on the IC50 value of GSNO relative to the WT Vector cells. This indicated that the hyper-expression of any of these GSTs alone does not protect cells from GSNO in the absence of high MRP1 levels. However, all VP cell types were significantly (p < 0.001) more resistant to the cytotoxic effect of GSNO when compared with the WT cells (Fig. 7A, panel i), supporting a role for MRP1 in the NO detoxification process. Transfection of VP cells with GSTA1 (VPα) or GSTM1 (VPμ) had no effect on the cytotoxic activity of GSNO, whereas transfection with GSTP1 (VPπ) led to a significant (p < 0.001) increase in the IC50, indicating greater resistance to GSNO (Fig. 7A, panel i). Together, these results indicate that the presence of both GST P1-1 and MRP1 is necessary for maximum resistance to the cytotoxic effects of GSNO. Furthermore, it demonstrates the functional relationships of these two proteins in GSNO metabolism and reflects synergistic partnership roles in DNIC storage and transport. Hence, as found for cytotoxic chemotherapeutics (17, 18, 20), GST P1-1 and MRP1 act together to suppress the cytotoxic activity of NO.

FIGURE 7.

MRP1 and GST P1-1 cooperate in preventing the cytotoxic activity of NO. A, panel i, co-expression of both MRP1 and GST P1-1 (but not GST A1-1 or GST M1-1) is required for maximum resistance against NO as GSNO. WT Vector cells, VP Vector/Vector* cells, and WT/VPα, VPμ, or VPπ cells were incubated with GSNO (0.02–10 mm) for 72 h at 37 °C, and proliferation was assessed. The expression of both GST P1-1 and MRP1 in VPπ cells leads to maximum resistance to the cytotoxicity of GSNO. Panel ii, co-expression of MRP1 and GST P1-1 in VPπ cells leads to greatest sensitivity to GSNO when cells were preincubated with BSO (0.1 mm) for 20 h at 37 °C and then incubated with GSNO (0.02–10 mm) for 72 h at 37 °C; proliferation was assessed after these experiments. B, the cytotoxic effect of GSNO and MRP1 inhibitors on cell proliferation in MRP1 hyper-expressing cells in the absence or presence of GST P1-1. The WTπ and VPπ cells and their relevant vector control cells were incubated with either GSNO (0.02–10 mm) or MK571 (20 μm) and GSNO (0.02–10 mm) (panel i) or GSNO (0.02–10 mm) or sulfinpyrazone (2 mm) and GSNO (0.02–10 mm) (panel ii) for 72 h at 37 °C, and proliferation was assessed. C, the effect of GST inhibitors in cells hyper-expressing MRP1 in the absence or presence of GST P1-1. The WTπ and VPπ cells and their relevant vector control cells were incubated with either GSNO (0.02–10 mm) or ethacrynic acid (200 μm) and GSNO (0.02–10 mm) (panel i) or GSNO (0.02–10 mm) or dicumarol (1.25 mm) and GSNO (0.02–10 mm) (panel ii) for 72 h at 37 °C, and proliferation was assessed. Results are mean ± S.D. (3–5 experiments). ***, p < 0.001.

Throughout our studies, we used two chemically different NO donors (namely GSNO and SperNO; see Figs. 1, B and C, and 2C and supplemental Fig. S3) and both have demonstrated basically equivalent effects, namely, they induce NO-mediated cellular iron release via MRP1 (Fig. 1, B and C); both have the same effect via GSTπ on preventing cellular iron release (Fig. 2C); and both NO generators lead to the same EPR spectra in cells (supplemental Fig. S3). Moreover, our studies with these NO generators have also been confirmed by transfecting cells with iNOS (Figs. 1D and 3D). Hence, in our system, SperNO and GSNO are acting in a similar way. In fact, we also showed that GST P1-1 hyper-expressing VP cells were more resistant than their empty vector-transfected VP counterparts to the effects of SperNO, as shown for GSNO (Fig. 7A, panel i).

Studies were then focused on the effect of the GSH inhibitor, BSO (Fig. 7A, panel ii); MRP1 inhibitors MK571 and sulfinpyrazone (12, 20) (Fig. 7B, panels i and ii); and GST inhibitors ethacrynic acid and dicumarol (20, 30) (Fig. 7C, panels i and ii) on the cytotoxic activity of GSNO in WTπ and VPπ cells. For all inhibitors, the most marked effects of sensitizing cells to the cytotoxic activity of NO were observed in cells hyper-expressing both MRP1 and GST P1-1. This implies that disruption of the partnership between these proteins results in problems in handling and trafficking NO, leading to greater cytotoxic activity.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to show that an integrated NO storage and transport mechanism exists within mammalian cells that utilizes a cooperative interaction between GST P1-1 and MRP1. The evidence for this mechanism includes the following; 1) GST P1-1, but not GST A1-1 or GST M1-1, acts to prevent NO-mediated 59Fe release from MRP1-hyper-expressing VP cells (Fig. 3, A–D); 2) Prevention of 59Fe efflux occurs via the binding of 59Fe to GST P1-1, probably as a DNIC (14), as shown by concomitant 59Fe accumulation in cellular fractions containing GST P1-1 (but not GST A1-1 or GST M1-1; Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S1, A and B); 3) Iron accumulation leads to a unique and much stronger DNIC EPR signal in VP cells transfected with GSTP1 (Fig. 5A, panel viii) relative to VP Vector cells (Fig. 5A, panel vii), but does not occur in those cells transfected with GSTA1 (Fig. 5B, panel ii) or GSTM1 (Fig. 5B, panel iii) relative to VP Vector* cells (Fig. 5B, panel i); 4) Cells expressing both MRP1 and GST P1-1 are significantly more resistant to the cytotoxic effects of GSNO than cells expressing GST P1-1 or MRP1 alone or cells expressing MRP1 and other GST isoforms (Fig. 7A, panel i); 5) For all MRP1 and GST inhibitors (Fig. 7A, panel ii, and B and C), the most marked effects of sensitizing cells to GSNO were observed in cells hyper-expressing both MRP1 and GST P1-1, demonstrating that disturbance of the relationship between these proteins leads to greater NO-mediated cytotoxicity. Collectively, these data indicate a unique role of GST P1-1 in both NO and iron metabolism and also the cooperative relationship between GST P1-1 and MRP1.

We previously showed that GSH was essential for NO-mediated iron mobilization from cells (10) and that the GSH transporter, MRP1, was involved in NO-mediated efflux of iron and GSH from cells in a form consistent with DNICs (12). Further, GST enzymes bind DNICs with very high affinity and could act as a storage form of NO for regulating intracellular processes (14, 27). Most of these previous studies examining DNIC-GST complexes have been performed on purified proteins (14, 27), and none of these have examined the cooperative role of GSTs and MRP1 on intracellular iron trafficking and release in mammalian cells. However, EPR studies by Pedersen et al. (27) using cultured rat hepatocytes and liver homogenates showed that DNICs may bind to α class GSTs. This is inconsistent with our current work, where GST A1-1 hyper-expression did not influence NO-mediated 59Fe release (Fig. 3A), nor did it bind intracellular 59Fe (supplemental Fig. S1A). Further, GST A1-1 did not significantly increase or lead to a unique EPR signal relative to VP Vector* cells (Fig. 5B, panels i and ii). The discordance likely relates to the metabolic differences between rat and human cells and the cell types studied as GSTs demonstrate tissue-specific distributions and functions (27). Consistent with this idea, it is worth discussing that MCF7 cells naturally express GST P1-1 rather than GST A1-1 or M1-1 (31). Thus, the metabolic machinery necessary for the interaction between GST P1-1 and MRP1 and the handling of DNICs could be present in these cells, whereas that for GST A1-1 or M1-1 may not exist.

The GST enzymes have long been associated with the multidrug resistance of tumor cells, and the cooperative relationship of MRP1 and GST P1-1 in drug resistance is well documented (16–18). In addition, it has been shown that GST expression is not always sufficient to confer protection from cellular toxins (20), and in some cell types, GSTs must be co-expressed with MRP1 to optimally protect cells from anticancer agents (16, 32). Until this investigation, the combined effect of these proteins on NO metabolism and its cytotoxicity were unknown. Our studies show that when exposed to NO, VP cells were more resistant than their respective WT cells (Fig. 7A, panel i). However, although there was no significant difference in cytotoxicity between the VP Vector* and the VPα and VPμ cells, VPπ cells were significantly more resistant to the effect of NO. In the WT transfectants, there were no significant differences in the susceptibility to NO between the vector and all GST transfectants. These results highlight the importance of the combined effect of GST P1-1 and MRP1 in protecting cells from NO cytotoxicity, as found for other types of cytotoxic agents (18). This indicates that the storage function of GST P1-1 is not only important for preventing NO-mediated toxicity, but also the ability of MRP1 to efflux DNICs is crucial for optimal protection against NO-mediated cytotoxicity (12).

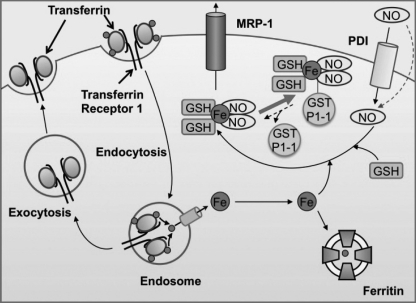

Central to our hypothesis is the concept of DNICs as a common currency for storage and transport of NO (Fig. 8). In fact, DNICs are a natural storage form of NO that possesses a longer half-life than NO alone (15). In addition, DNICs associate with GST to stabilize NO for many hours (15), which markedly exceeds the half-life of “free NO” (2 ms–2 s) (33). Further, DNICs permeate cells to donate iron and trans-nitrosylate molecular targets, demonstrating their bioavailability (1, 34).

FIGURE 8.

Schematic illustrating the respective roles of GST P1-1 and MRP1 in NO storage and transport. NO can diffuse through the membrane or may be actively transported into cells by protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) (37). Due to the ability of NO to act as a ligand, it can bind iron transported into cells and released from transferrin. GSH completes the NO-Fe complex to form a DNIC. DNICs can be bound by GST P1-1 or effluxed out of cells via MRP1.

Previous studies in vitro showed that DNICs inactivate glutathione reductase and that GSTs can prevent this and act to protect cells (27). Our work corroborates and extends these findings and demonstrates that GST P1-1 acts as an NO store that regulates DNIC release via MRP1 (Fig. 8). In this way, MRP1 could act to efflux DNICs once the binding capacity of GST P1-1 for DNICs is exceeded, preventing DNIC cytotoxicity.

Considering the interaction of GST P1-1 with NO, GSTP1 polymorphisms correlate with preeclampsia (35), and this may be related to the ability of these enzymes to bind and store vasoactive NO as DNICs (14). Indeed, the ability of the cell to actively transport, store, and traffic NO overcomes the random process of diffusion that would be inefficient and non-targeted (1). Finally, although our current work supports a significant role for GST P1-1 and MRP1 in the storage and transport of NO, we do not exclude the importance of other pathways of NO metabolism such as S-nitroso-thiols (36).

In summary, GST P1-1 is able to complex with DNICs intracellularly, and hence, prevents their efflux from cells via MRP1. Since GST enzymes and MRP1 form a closely integrated system for removing many toxins (16–18), our studies indicate that GST P1-1 regulates NO levels by storing and transporting DNICs, respectively. This could have crucial consequences for NO signaling, NO-mediated apoptosis, and the cytotoxicity of MØs that is due, in part, to iron release from tumor target cells.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Discovery Grant DP1092734 from the Australian Research Council (to D. R. R.) and a Canadian Institute of Health research grant (to P. P.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- MØ

- activated macrophage

- BSO

- l-buthionine-(S,R)-sulfoximine

- DNIC

- dinitrosyl-dithiol iron complex

- GSNO

- S-nitroso-glutathione

- iNOS

- inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MEF

- murine embryonic fibroblast

- MRP1

- multidrug resistance protein 1

- SperNO

- spermine NONOate

- Tf

- transferrin

- VP

- MCF7-VP cells

- WT

- MCF7-WT cells.

REFERENCES

- 1. Watts R. N., Ponka P., Richardson D. R. (2003) Biochem. J. 369, 429–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hibbs J. B., Jr., Taintor R. R., Vavrin Z. (1984) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 123, 716–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bosworth C. A., Toledo J. C., Jr., Zmijewski J. W., Li Q., Lancaster J. R., Jr. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4671–4676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Drapier J. C., Hibbs J. B., Jr. (1986) J. Clin. Invest. 78, 790–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harrop T. C., Tonzetich Z. J., Reisner E., Lippard S. J. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15602–15610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vanin A. F. (1991) FEBS Lett. 289, 1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lancaster J. R., Jr., Hibbs J. B., Jr. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 1223–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bastian N. R., Yim C. Y., Hibbs J. B., Jr., Samlowski W. E. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 5127–5131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hickok J. R., Sahni S., Shen H., Arvind A., Antoniou C., Fung L. W., Thomas D. D. (2011) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51, 1558–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Watts R. N., Richardson D. R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4724–4732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wardrop S. L., Watts R. N., Richardson D. R. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 2748–2758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Watts R. N., Hawkins C., Ponka P., Richardson D. R. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7670–7675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Griffith O. W., Meister A. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254, 7558–7560 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cesareo E., Parker L. J., Pedersen J. Z., Nuccetelli M., Mazzetti A. P., Pastore A., Federici G., Caccuri A. M., Ricci G., Adams J. J., Parker M. W., Lo Bello M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42172–42180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turella P., Pedersen J. Z., Caccuri A. M., De Maria F., Mastroberardino P., Lo Bello M., Federici G., Ricci G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42294–42299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morrow C. S., Smitherman P. K., Diah S. K., Schneider E., Townsend A. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20114–20120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morrow C. S., Smitherman P. K., Townsend A. J. (1998) Biochem. Pharmacol. 56, 1013–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morrow C. S., Diah S., Smitherman P. K., Schneider E., Townsend A. J. (1998) Carcinogenesis 19, 109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu X., Sutak R., Richardson D. R. (2008) Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 833–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Depeille P., Cuq P., Passagne I., Evrard A., Vian L. (2005) Br. J. Cancer 93, 216–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zaman K., Palmer L. A., Doctor A., Hunt J. F., Gaston B. (2004) Biochem. J. 380, 67–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nath N., Morinaga O., Singh I. (2010) J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 5, 240–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choi J. W., Im M. W., Pai S. H. (2002) Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 32, 257–263 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalinowski D. S., Richardson D. R. (2005) Pharmacol. Rev. 57, 547–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. MacLeod A. K., McMahon M., Plummer S. M., Higgins L. G., Penning T. M., Igarashi K., Hayes J. D. (2009) Carcinogenesis 30, 1571–1580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kielar D., Kaminski W. E., Liebisch G., Piehler A., Wenzel J. J., Möhle C., Heimerl S., Langmann T., Friedrich S. O., Böttcher A., Barlage S., Drobnik W., Schmitz G. (2003) J. Invest. Dermatol. 121, 465–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pedersen J. Z., De Maria F., Turella P., Federici G., Mattei M., Fabrini R., Dawood K. F., Massimi M., Caccuri A. M., Ricci G. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6364–6371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reddy D., Lancaster J. R., Jr., Cornforth D. P. (1983) Science 221, 769–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Richardson D. R., Lok H. C. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 638–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Depeille P., Cuq P., Mary S., Passagne I., Evrard A., Cupissol D., Vian L. (2004) Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 897–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Luca A., Moroni N., Serafino A., Primavera A., Pastore A., Pedersen J. Z., Petruzzelli R., Farrace M. G., Pierimarchi P., Moroni G., Federici G., Sinibaldi Vallebona P., Lo Bello M. (2011) Biochem. J. 440, 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harbottle A., Daly A. K., Atherton K., Campbell F. C. (2001) Int. J. Cancer 92, 777–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomas D. D., Liu X., Kantrow S. P., Lancaster J. R., Jr. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 355–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Boese M., Mordvintcev P. I., Vanin A. F., Busse R., Mülsch A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 29244–29249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Canto P., Canto-Cetina T., Juárez-Velázquez R., Rosas-Vargas H., Rangel-Villalobos H., Canizales-Quinteros S., Velázquez-Wong A. C., Villarreal-Molina M. T., Fernández G., Coral-Vázquez R. (2008) Hypertens. Res. 31, 1015–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stamler J. S., Singel D. J., Loscalzo J. (1992) Science 258, 1898–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zai A., Rudd M. A., Scribner A. W., Loscalzo J. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 393–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.