Background: Methylglyoxal is a typical 2-oxoaldehyde derived from glycolysis.

Results: Methylglyoxal inhibited the activity of yeast hexose transporters as well as mammalian glucose transporters (GLUT1 and GLUT4) and enhanced the endocytosis of hexose transporters in yeast.

Conclusion: Methylglyoxal inhibited glucose uptake in yeast cells.

Significance: Phospholipase C and protein kinase C were involved in endocytosis of hexose transporters.

Keywords: E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Endocytosis, Metabolic Diseases, Phospholipase C, Yeast Physiology, Hexose Transporter

Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is characterized by an impairment of glucose uptake even though blood glucose levels are increased. Methylglyoxal is derived from glycolysis and has been implicated in the development of diabetes mellitus, because methylglyoxal levels in blood and tissues are higher in diabetic patients than in healthy individuals. However, it remains to be elucidated whether such factors are a cause, or consequence, of diabetes. Here, we show that methylglyoxal inhibits the activity of mammalian glucose transporters using recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells genetically lacking all hexose transporters but carrying cDNA for human GLUT1 or rat GLUT4. We found that methylglyoxal inhibits yeast hexose transporters also. Glucose uptake was reduced in a stepwise manner following treatment with methylglyoxal, i.e. a rapid reduction within 5 min, followed by a slow and gradual reduction. The rapid reduction was due to the inhibitory effect of methylglyoxal on hexose transporters, whereas the slow and gradual reduction seemed due to endocytosis, which leads to a decrease in the amount of hexose transporters on the plasma membrane. We found that Rsp5, a HECT-type ubiquitin ligase, is responsible for the ubiquitination of hexose transporters. Intriguingly, Plc1 (phospholipase C) negatively regulated the endocytosis of hexose transporters in an Rsp5-dependent manner, although the methylglyoxal-induced endocytosis of hexose transporters occurred irrespective of Plc1. Meanwhile, the internalization of hexose transporters following treatment with methylglyoxal was delayed in a mutant defective in protein kinase C.

Introduction

Glucose is an easy-to-use energy source for all kinds of cells. However, because cellular membranes are not very permeable to glucose, cells are equipped with glucose transporters on the plasma membrane to take up glucose from outside of the cell. Many glucose transporters from prokaryotes to higher eukaryotes belong to the major facilitator superfamily, which is characterized by a single polypeptide carrier with 12 transmembrane domains capable of transporting substrates across the membrane in response to a chemiosmotic gradient (1–3). For example, if the glucose concentration outside of cells is higher, glucose transporters take up glucose from the outside, but when the intracellular glucose concentration is higher than outside, they pump out glucose.

Although glucose is necessary as an energy source, glucose homeostasis in blood is crucial for mammals. Diabetes mellitus is characterized by a disruption of glucose homeostasis. When blood glucose levels increase upon food intake, insulin is secreted from pancreatic β cells. The insulin signaling pathway in cells possessing insulin receptors is activated upon receipt of insulin, which leads to the translocation of a glucose transporter, GLUT4, to the plasma membrane thereby facilitating the influx of glucose (4). In type 1 diabetes, insulin secretion is defective, whereas in type 2 diabetes, cells are insensitive to insulin (insulin resistance), which seems to be caused by lifestyle. In both cases, cells are impaired in taking up glucose from blood, and consequently, hyperglycemic situations develop, which leads to the induction of several diabetic complications. One of the causes of diabetic complications is the accumulation of advanced glycation end products, the synthesis of which is initiated by a nonenzymatic reaction between the aldehyde groups of glucose and amino groups of proteins, sometimes referred to as the Maillard reaction (5). Methylglyoxal (MG,3 CH3COCHO) is a ubiquitous 2-oxoaldehyde derived from glycolysis (6–8). Because MG contains two carbonyl groups, it has a 20,000-fold higher potential than glucose to produce advanced glycation end products (9). Therefore, MG levels and diabetic complications are closely related (10). The levels of MG in blood and tissues are higher in diabetic patients than healthy individuals (11–13). However, it remains to be solved whether high MG levels are a cause or a consequence of diabetes. Furthermore, the correlation between the onset of hyperglycemic conditions and an increase in MG levels has not been well investigated.

One feature of diabetes mellitus is that the hyperglycemia is sustained even in a fasted state. The control of blood glucose levels mainly depends upon whether glucose transporters can transport glucose adequately (14, 15). To date, 13 glucose transporters, GLUT1-GLUT12 and Hmit1, have been identified in mammals (2, 3). These transporters are responsible for the supply of glucose to various tissues, storage of glucose (glycogen) in liver, uptake of glucose in response to insulin, and sensing of blood glucose levels in pancreatic β cells (16–18). Mammalian glucose transporters are classified into three groups on the basis of primary structure (19). GLUT1–GLUT4 belong to a major facilitator superfamily (3). GLUT1, the first glucose transporter to be identified (20), is distributed in almost all tissues, and therefore, it is thought to play a crucial role in glucose homeostasis under normal conditions (19). Because only GLUT4 is sensitive to insulin, it is involved in controlling blood glucose levels upon food intake (15).

Because yeast has served as a model of higher eukaryotes to reveal the mechanisms of many pivotal biological events, it is feasible that we will gain a clue as to the effect of MG on the function of mammalian GLUTs by analyzing the effect of MG on yeast glucose transporters. In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, glucose transporters are referred to as hexose transporters (Hxts). S. cerevisiae has 17 hexose transporters (Hxt1–Hxt17) and Gal2 as a galactose permease, all of which belong to a major facilitator superfamily (21). We found that MG inhibits the activities of not only yeast Hxts but also mammalian GLUTs. Furthermore, MG induced endocytosis of yeast Hxts in an Rsp5 (HECT-type ubiquitin ligase)-dependent manner, thereby lowering glucose uptake. We found that protein kinase C (Pkc1) is involved in the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts. Intriguingly, a deficiency in phospholipase C (Plc1) accelerated the internalization of Hxts under normal conditions in an Rsp5-dependent manner. However, the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts occurred independently of Plc1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media

The media used were YPD (2% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone), YPMal (2% maltose, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone), SD (2% glucose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids), SGal (2% galactose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids), and SMal (2% maltose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids). Appropriate amino acids and bases were added to the SD, SGal, and SMal media as necessary. To select the HXT null mutant carrying a plasmid (URA3 marker) harboring human GLUT1 cDNA or rat GLUT4 cDNA, cells were first spread on to YPMal agar (2%) plates after transformation, and cells grown on YPMal agar plates were replica plated on SMal agar plates without uracil. After verification of growth in SMal agar plates without uracil, cells were streaked on SD agar plates without uracil to verify the functional expression of GLUT1 and GLUT4.

Strains

Yeast strains used are summarized in Table 1. To construct an rsp5wimp (RSP5 low level expression) mutant with the YPH250 background, the natMX-inserted RSP5 promoter region of EN44 (22) was amplified by PCR with primers RSP5-F and RSP5-R-2. The PCR fragment was introduced into the RSP5 locus of YPH250. To construct a plc1Δ mutant, a plc1Δ::HIS3 allele of YJF32 (23) was amplified by PCR with PLC1-F and PLC1-R-2, and the product was introduced into the wild-type strain or rsp5wimp mutant of YPH250. To disrupt the SCH9 gene in YPH250, an sch9Δ::TRP1 allele of TVH301 (24) was amplified with primers SCH9-F and SCH9-R, and the amplicon was introduced into YPH250. Primers used in this study are summarized in supplemental Table S1.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype/description | Source/Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| YPH250 | MATa trpΔ1-1 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 lys2-801 ade2-101 ura3-52 | Lab stock |

| BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Invitrogen |

| rsp5wimp | YPH250, natMX was inserted into the promoter of RSP5 | This study |

| plc1Δ | YPH250, plc1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| plc1Δrsp5wimp | YPH250, plc1Δ::HIS3 rsp5wimp | This study |

| sch9Δ | YPH250, sch9Δ::TRP1 | This study |

| doa4Δ | BY4741, doa4Δ::KanMX4 | This study |

| mpk1Δ | DL100, mpk1Δ::KanMX4 | This study |

| EN44 | BY4741, natMX was inserted into the promoter of RSP5 | 22 |

| MBY242 | MATa his4 ura3 leu2 lys2 bar1 HXT2-PA::URA3 | 27 |

| YJF32 | MATa ura3-52 lys2-801_amber ade2-101_ochre trp1-Δ63 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 plc1Δ::HIS3 | 23 |

| TVH301 | MATa ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 sch9::TRP1 | 25 |

| KY73 | MATa hxt1Δ::HIS3::Δhxt4 hxt5::LEU2 hxt2Δ::HIS3 hxt3Δ::LEU2::hxt6 hxt7::HIS3 gal2Δ::DR ura3–52 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 MAL2 SUC2 GAL MEL | 26 |

| EBY.S7 | MATa hxt1-17Δgal2Δagt1Δstl1Δleu2-3,112 ura3-52 trp1-289 his3-Δ1 MAL2–8c SUC2 hxtΔfgy1-1 | 28 |

| EBY.F4–1 | MATa hxt1-17Δgal2Δagt1Δstl1Δleu2-3,112 ura3-52 trp1-289 his3-Δ1 MAL2-8c SUC2 hxtΔfgy1-1 fgy41 | 28 |

| TB50a | MATa his3 leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 rme1 trp1 | 40 |

| RL25–1C | TB50a, [KanMX4]-GAL1p-3HA-AVO1 | 40 |

| DL100 | MATa leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-52 his4 can1 | 60 |

| DL376 | DL100, pkc1Δ::LEU2 | 60 |

Plasmids

To construct the integration plasmids for Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, and Hxt3-GFP, each HXT gene (HXT1, +401 to +1720; HXT2, +304 to +1640; and HXT3, +687 to +1724) was amplified with the following primer sets: HXT1, HXT1-F-XbaI plus HXT1-R-XhoI; HXT2, HXT2-F-XbaI plus HXT2-R-XhoI; and HXT3, HXT3-F-XbaI plus HXT3-R-XhoI. Each PCR product was digested with XbaI and XhoI, and the resultant fragment was introduced into the XhoI and XbaI sites of YIp-NUP116-GFP (25), a pRS306 backbone plasmid, to replace NUP116 with each HXT gene. The plasmids constructed (pHXT1-GFP, pHXT2-GFP, and pHXT3-GFP) were digested with HpaI, and the linearized DNA was introduced at the loci of HXT1, HXT2, and HXT3, respectively, to replace each gene containing a GFP tag.

We verified that each Hxt-GFP protein is functional as a glucose transporter by evaluating the recovery of growth of K73 cells in glucose medium. Because K73 lacks HXT1–7, it is not able to grow in glucose medium (26). However, because HXT1, HXT2, and HXT3 are deleted in K73, we cannot integrate GFP into each HXT locus to construct HXT-GFPs. So we constructed plasmid-borne Hxt-GFPs. YIp-NUP116-GFP (25) was digested with XhoI and KpnI, and the XhoI-KpnI fragment containing GFP and NUF2 3′ UTR was cloned into the XhoI-KpnI sites of pRS316. The resultant plasmid was named pRS316-GFP. Each HXT gene with its own promoter was amplified by PCR with the following primer sets: HXT1, HXT1-F-SacI plus HXT1-R-XhoI; HXT2, HXT2-F-SacI plus HXT2-R-XhoI; and HXT3, HXT3-F-SacI plus HXT3-R-XhoI. Each PCR product was digested with SacI and XhoI, and the resultant fragment was cloned into the SacI and XhoI sites of pRS316-GFP. The plasmids constructed (pRS316 + HXT1-GFP, pRS316 + HXT2-GFP, and pRS316 + HXT3-GFP) contain the same HXT-GFP allele with that of the genome-integrated HXT-GFP gene. K73 cells carrying each plasmid were able to grow in glucose medium, indicating that Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, and Hxt3-GFP proteins are functional as glucose transporters.

To construct the integration plasmids for HXT1-lacZ, HXT2-lacZ, and HXT3-lacZ, the promoter region of each HXT gene was amplified with the following primer sets: HXT1, HXT1-lacZ-F plus HXT1-lacZ-R; HXT2, HXT2-lacZ-F plus HXT2-lacZ-R; and HXT3, HXT3-lacZ-F plus HXT3-lacZ-R. Each PCR product was digested with SalI and EcoRI, and the resultant fragment was introduced into the SalI and EcoRI sites of YIp358R. The plasmids constructed (YIp358R + HXT1-lacZ, YIp358R + HXT2-lacZ, and YIp358R + HXT3-lacZ) were digested with NcoI and integrated into the ura3-52 locus of the wild-type and plc1Δ mutant of YPH250. Plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Source/Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| pHXT1-GFP | pRS306 (integrate-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for replacement of endogenous HXT1 with HXT1-GFP | This study |

| pHXT2-GFP | pRS306 (integrate-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for replacement of endogenous HXT2 with HXT2-GFP | This study |

| pHXT3-GFP | pRS306 (integrate-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for replacement of endogenous HXT3 with HXT3-GFP | This study |

| pRS316 + PMA1-GFP | pRS316 (CEN-type, URA3 marker) harboring Pma1-GFP | 61 |

| pFL44 + RVS161-GFP | pFL44 (CEN-type, URA3 marker) harboring Rvs161-GFP | 61 |

| YIp358R + HXT1-lacZ | YIp358R (integrate-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for fusion with HXT1 and lacZ | This study |

| YIp358R + HXT2-lacZ | YIp358R (integrate-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for fusion with HXT2 and lacZ | This study |

| YIp358R + HXT3-lacZ | YIp358R (integrate-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for fusion with HXT3 and lacZ | This study |

| Hxt1mnx-pVT | pVT102-U (2μ-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for expression of HXT1 | 62 |

| Hxt2mnx-pVT | pVT102-U (2μ-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for expression of HXT2 | 62 |

| pVT102-U/His-Xa-human-GLUT1 | pVT102-U (2μ-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for expression of human GLUT1 cDNA | T. Kasahara, unpublished data |

| pVT102-U/rat-GLUT4 | pVT102-U (2μ-type, URA3 marker) backbone, for expression of rat GLUT4 cDNA | T. Kasahara, unpublished data |

Glucose Uptake Experiment

Cells were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth, and 10 mm MG was added. Next, 5 ml of culture was taken at the prescribed time and transferred to a 15-ml Falcon tube, and 10 μl of [14C]glucose (10.6 GBq/mmol, GE Healthcare) was added. Cells were then collected, washed with a chilled 0.85% NaCl solution, and suspended in 200 μl of distilled water. The cell suspension (150 μl) was mixed with 2 ml of a liquid scintillation mixture (Ultima-Flo AP, PerkinElmer Life Sciences), and the amount of [14C]glucose taken up by cells was measured using a scintillation counter (LS6500, Beckman Coulter). When cells were treated with latrunculin B (Lat-B, BIOMOL International), cells were pretreated with 100 μm Lat-B for 20 min prior to the addition of MG.

Western Blotting of GFP-tagged Hxts

Cells carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were cultured in 200-ml flasks containing 50 ml of SD medium until a log phase of growth (A610 = ∼0.5); 10 mm MG was added, and the cells were incubated for the prescribed time. After being collected by centrifugation, cells were disrupted with glass beads in 100 μl of buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mm EDTA, 5% glycerol, and protease inhibitor mixture (Nacalai Tesque)) using BeadSmash 12 (Waken). Cell homogenates were kept on ice for 2 min and transferred to another tube. The resulting glass beads were mixed with 100 μl of buffer A and kept on ice for 2 min. The supernatant was mixed with the first cell homogenate, which was then centrifuged at low speed (3000 rpm for 2 min at 4 °C) to remove unbroken cells and cell debris, and the resultant supernatant, referred to as whole cell extract (WCE), was transferred to another tube. WCE was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant (soluble fraction) and pellet (insoluble fraction) were separated. The pellet was suspended in 75 μl of IPP150 buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Nonidet P-40) containing 1% n-octyl-β-d-glucoside (Dojin) and protease inhibitor mixture, and the suspension was kept on ice for 1 h and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used as a membrane fraction. The soluble fraction (4 μg of protein) and membrane fraction (40 μg of protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Separated proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore) and then detected using anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunoreacted bands were visualized with a kit (Immobilon Western chemiluminescent HRP substrate, Millipore) using a LAS-4000 mini imaging system (FUJIFILM).

Detection of Ubiquitination

To prepare the membrane fraction containing protein A-tagged Hxt2 (Hxt2-PA), MBY242 cells carrying the HXT2-PA gene (27) were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth and then transferred to fresh medium containing 0.1% glucose and 0.67% yeast nitrogen base (without amino acids) supplemented with appropriate amino acids and bases. After 1 h, cells were collected and disrupted as described above. WCE was ultracentrifuged at 50,000 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C (himac CS120, Hitachi). The pellet was suspended in buffer A and ultracentrifuged again. The resultant pellet was suspended in IPP150 buffer containing 1% n-octyl-β-d-glucoside. After a 1-h incubation on ice, the cell suspension was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was transferred to a tube containing 50 μl of IgG beads (IgG-SepharoseTM 6 Fast Flow, Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with IPP150 buffer. To adsorb the protein A-tagged Hxt2 to IgG beads, the mixture was gently rotated at 4 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, IgG beads were washed with 1 ml of IPP150 buffer three times, and then 0.9 ml of 100 mm glycine-HCl buffer (pH 3.5) was added to elute Hxt2-PA. After centrifugation, the supernatant was mixed with 100% trichloroacetic acid (final concentration, 10%), and the mixture was kept on ice for 10 min to precipitate proteins. After removal of the supernatant by centrifugation (14,000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C), the pellet was washed with acetone, and dried materials were dissolved in 25 μl of 1 m Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). After that, 25 μl of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added, and the mixture was boiled for 3 min. Protein concentrations were determined using a RC DC Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad). After SDS-PAGE followed by the transfer of separated proteins onto a PVDF membrane, Hxt2-PA and its ubiquitinated form were detected using anti-protein A (Lockland) and anti-ubiquitin (BIOMOL International LP) antibodies, respectively.

Western Blotting of Hxts1/2 and GLUTs1/4

KY73 (hxt1-7Δ) (26) carrying a plasmid harboring HXT1 or HXT2, EBY.S7 (hxtΔ fgy1-1) (28) carrying GLUT1 cDNA, or EBY.F4-1 (hxtΔ fgy1-1 fgy4-1) (28) carrying GLUT4 cDNA was cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth, and the membrane fraction was prepared by ultracentrifugation as described above. Anti-Hxt1, anti-Hxt2, anti-GLUT1, and anti-GLUT4 antibodies, which were donated by Dr. T. Kasahara, were used to detect proteins. To detect Pma1, an anti-Pma1 antibody (Encor Biotechnology) was used.

Microscopy

Cells carrying GFP-tagged proteins were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth, and 10 mm MG was added. The localization of each protein of interest was determined periodically using a fluorescence microscope. To stain vacuoles, 10 ml of culture was centrifuged to collect cells, which were then suspended in 196 μl of YPD medium. Four microliters of 2 mm FM4-64 (Biotium) was added to the cell suspension and incubated at 28 °C in the dark. After 20 min of incubation, 1 ml of a 0.85% NaCl solution was added to the cell suspension and centrifuged to collect the cell. Cells were then suspended in fresh SD medium and incubated for the prescribed time in the presence or absence of MG at 28 °C.

RESULTS

MG Inhibits Glucose Uptake in Yeast

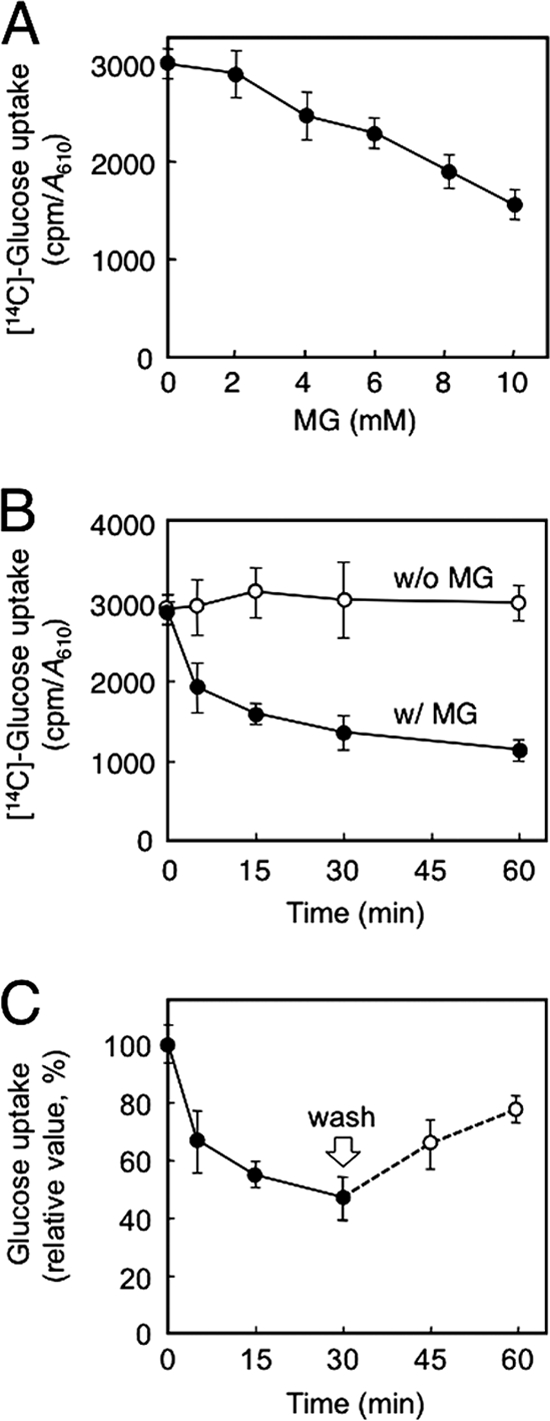

To explore the effect of MG on the function of hexose transporter (Hxt), we determined the rate of glucose uptake by yeast cells in the presence of MG. [14C]Glucose was added to the culture in which yeast cells were growing logarithmically, and the amount of [14C]glucose taken up by cells was determined. Fig. 1A shows the levels of [14C]glucose uptake after 15 min of the addition of various concentrations of MG. Glucose uptake was inhibited in the presence of MG in a dose-dependent manner, and ∼50% inhibition was attained by 10 mm MG. Next, we determined the time course of the effect of MG on inhibition of glucose uptake. The rate of uptake dropped by 35% within the first 5 min after the addition of 10 mm MG, after which it declined gradually. It had decreased by ∼60% after 60 min compared with that in the absence of MG. Several explanations are feasible regarding the reduction of glucose uptake following treatment with MG. For example, MG inhibited the activity of Hxts, or the number of Hxt molecules on the plasma membrane was decreased by endocytosis followed by degradation in vacuoles. To study these possibilities, we first determined whether endocytosis of Hxts occurred upon MG stress.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of MG on glucose uptake. A, cells (YPH250) were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth, and MG at various concentrations was added. After 15 min, glucose uptake was determined as described under “Materials and Methods.” B, cells (YPH250) were treated with 10 mm MG for the period indicated, and glucose uptake was determined. C, glucose uptake was measured after addition of 10 mm MG periodically. After 30 min, cells were collected by centrifugation, washed, and suspended in fresh SD medium without MG, and glucose uptake was determined (0 min was relatively taken as 100%). Data are averages for three independent experiments ± S.D. w/, with; w/o, without.

MG Induces Degradation of Hxts

S. cerevisiae has 17 HXT genes encoding glucose transporters. Because a mutant lacking one of these HXT genes is able to grow in a medium containing glucose as a source of carbon, these Hxts share redundant functions in terms of glucose uptake (21). However, because a mutant lacking HXT1 to HXT7 simultaneously loses the ability to grow in glucose medium (26), the rest of Hxts does not seem to play crucial roles in glucose uptake. The mRNAs of HXT1, HXT2, and HXT3 were abundant compared with those of other HXTs in cells cultured under ordinary laboratory conditions (i.e. containing 2% glucose) (29), so we determined the localization of GFP-tagged Hxt1, Hxt2, and Hxt3 as representatives of Hxts using a fluorescence microscope.

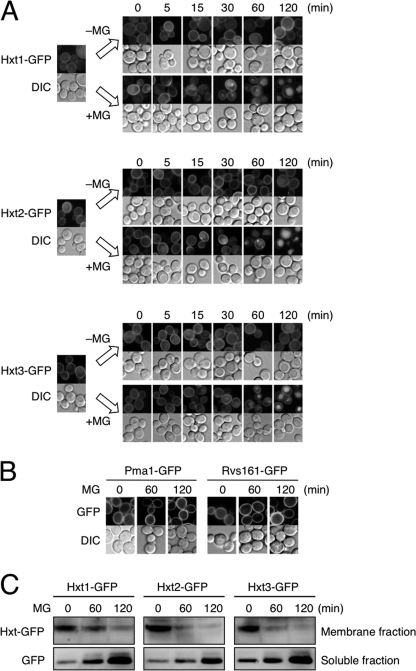

As shown in Fig. 2A, Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, and Hxt3-GFP were located on the plasma membrane at a log phase of growth; however, small punctate vesicles appeared after 15 min of MG treatment, which grew in size (30–60 min), and fluorescence derived from GFP-tagged proteins was observed in vacuoles (60–120 min). We investigated whether membrane proteins in general are also internalized following treatment with MG; however, other proteins such as Pma1 (plasma membrane H+-ATPase) and Rvs161 (amphiphysin-like lipid raft protein) were not internalized upon MG treatment (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

MG induces internalization and degradation of Hxts. A, cells (YPH250) carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth and treated with 10 mm MG for the period indicated. The distribution of each GFP-tagged Hxt was observed using a fluorescence microscope. DIC, differential interference contrast. B, cells carrying Pma1-GFP or Rvs161-GFP were treated with 10 mm MG for the period indicated, and the distribution of each GFP-tagged protein was determined. C, cells carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were treated with MG as described in A, membrane and soluble fractions were prepared, and the amount of each GFP protein was determined by Western blotting.

To verify whether the amount of Hxt1–3 on the plasma membrane is decreased following treatment with MG, Western blotting was conducted. As shown in Fig. 2C, the levels of Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, and Hxt3-GFP in membrane fractions decreased with time. By contrast, the levels of GFP protein in soluble fractions, which are derived from GFP-tagged Hxt1–3 by degradation in vacuoles, were increased. These results indicate that Hxt1–3 are internalized and degraded in the vacuole following treatment with MG.

MG Induces Endocytosis of Hxts

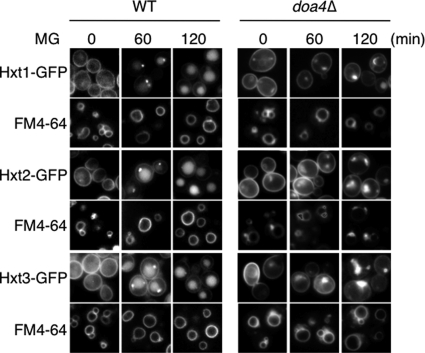

The endocytotic membrane vesicles fuse with endosomes, on which membrane the ubiquitin-modified cargo proteins are located, and subsequently, the components constituting the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) assemble on the endosomal membrane to internalize the cargo proteins into the lumen of endosomes, which are referred to as multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (30). The deubiquitination is preceded by the internalization of cargo proteins into the luminal side of endosomes. In yeast cells, Doa4 is responsible for the deubiquitination of ubiquitin-modified cargo proteins in this process (31). The MVBs containing the internalized vesicles with deubiquitinated cargo proteins fuse with vacuoles, and consequently, degradation of MVBs occurs in the lumen of vacuoles. If deubiquitination of ubiquitin-modified cargo proteins does not occur, such endosomes are not able to develop to MVBs and therefore are unable to fuse with vacuoles (31). Such endosomes form the so-called “ring-like structure” in the immediate vicinity of the vacuole, which can be visualized by staining endosomal membranes with a fluorescent dye, FM4-64 (32). To verify whether internalized Hxts are transported into the vacuole, we stained cells for vacuoles with FM4-64, and localization of Hxt1/2/3-GFPs was determined following treatment with MG. As shown in Fig. 3, GFP signals of each Hxt-GFP were observed in the vacuole, which was visualized with FM4-64. Next, to investigate whether transportation of Hxt1–3 into the vacuole in the presence of MG is performed via the MVB pathway, we monitored the localization of Hxt1/2/3-GFPs in doa4Δ cells. As shown in Fig. 3, GFP-tagged Hxt1–3 accumulated in close proximity to the vacuolar membrane to form the ring-like structure, and no fluorescence signal was detected from the vacuolar lumen in doa4Δ cells. These results indicate that endocytosis of Hxts occurs upon MG treatment, and subsequently, internalized Hxts are transported into vacuoles via the MVB pathway for degradation.

FIGURE 3.

Doa4 is involved in the endocytosis of Hxts. Wild-type and doa4Δ mutant (BY4741 background) carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth and treated with 10 mm MG for the period indicated. The distribution of each Hxt-GFP was observed using a fluorescence microscope. Vacuolar membrane was stained by FM4-64.

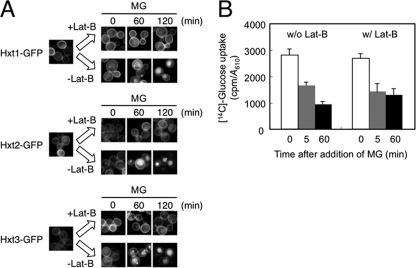

MG Inhibits the Activity of Hxt

We have demonstrated that MG induces the internalization of Hxt1, Hxt2, and Hxt3, thereby seemingly reducing the ability of yeast cells to take up glucose. The reduction of glucose uptake following treatment with MG occurred in a stepwise manner, i.e. a rapid response within 5 min and a slow and gradual response thereafter (Fig. 1B). Because the internalization of Hxts occurred relatively slowly, the reduction in glucose uptake that occurred within 5 min is not likely dependent upon a decrease in the number of Hxts on the plasma membrane. To determine whether a rapid reduction of glucose uptake upon MG stress occurs irrespective of the endocytosis of Hxts, we measured glucose uptake under conditions where endocytosis is blocked. The actin cytoskeleton plays a crucial role in endocytosis; therefore, the depolymerization of F-actin blocks endocytosis. Lat-B as well as Lat-A depolymerize F-actin (33), thereby blocking endocytosis (34). We verified that endocytosis of Hxt1/2/3-GFPs following treatment with MG was blocked when Lat-B was present (Fig. 4A). We then determined glucose uptake within the first 5 min of treatment with MG in the presence of Lat-B. As shown in Fig. 4B, the reduction in glucose uptake was substantially the same as that without Lat-B, suggesting that MG inhibits the activity of Hxt per se, and a rapid reduction in glucose uptake occurs irrespective of the endocytosis of Hxts.

FIGURE 4.

MG inhibits the activity of Hxts. A, cells (YPH250) carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth and treated with 100 μm Lat-B for 20 min prior to treatment with 10 mm MG. The distribution of each Hxt-GFP was observed using a fluorescence microscope. B, cells were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth, and 100 μm Lat-B was added. After 20 min, [14C]glucose was added. Glucose uptake in the first 5 and 60 min after addition of MG was determined as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data are averages for three independent experiments ± S.D. w/, with; w/o, without.

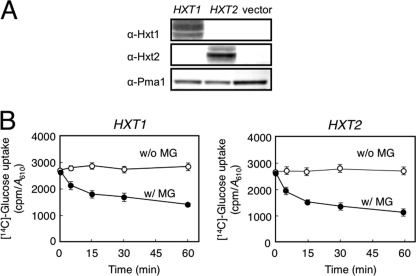

MG Inhibits Hxt1 and Hxt2

Next, to explore whether the inhibitory effect of MG on glucose uptake differs depending upon Hxt's affinity for glucose, we used a mutant (K73) lacking HXT1-HXT7 (hxt1–7Δ) but carrying a plasmid harboring either HXT1 or HXT2. K73 cells were not able to grow in glucose medium but were in maltose medium, because the maltose permeases in K73 remain intact (26). HXT1 codes for a low affinity glucose transporter, and HXT2 codes for a high affinity transporter (21). We verified that the growth of K73 cells in glucose medium was restored by the introduction of a plasmid harboring either HXT1 or HXT2, which indicates that the introduced HXT1 and HXT2 are functionally active in K73 cells. We verified by Western blotting that the Hxt1 and Hxt2 proteins were adequately located on the plasma membrane (Fig. 5A). We determined the glucose uptake using the resultant transformants. As shown in Fig. 5B, the glucose uptake was inhibited in K73 cells expressing HXT1 or HXT2 following treatment with MG, suggesting that the inhibitory effect of MG on the activity of Hxt is exerted irrespective of its affinity for glucose.

FIGURE 5.

MG inhibits Hxt activity. A, K73 (hxt1-7Δ) cells carrying Hxt1mnx-pVT harboring HXT1 (encoding a low affinity glucose transporter) or Hxt2mnx-pVT harboring HXT2 (encoding a high affinity glucose transporter) were cultured in SD medium. A membrane fraction was prepared from each transformant as described under “Materials and Methods.” Expression of HXT1 and HXT2 was verified by Western blotting using anti-Hxt1 and anti-Hxt2 antibodies, respectively. α-Pma1 indicates the loading control for the membrane fraction. B, glucose uptake of each transformant was determined as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data are averages for three independent experiments ± S.D. w/, with; w/o, without.

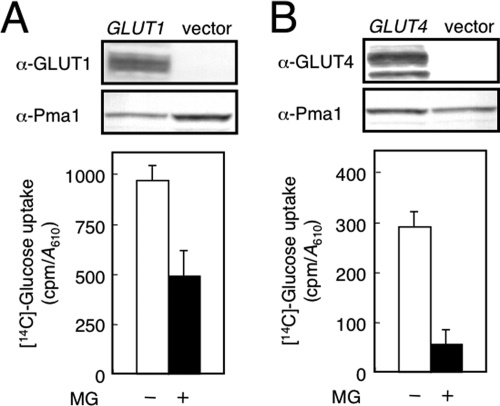

MG Inhibits Mammalian GLUTs

Because we revealed that MG inhibits the activity of a yeast glucose transporter or Hxt, we next determined whether MG inhibits the activity of a mammalian GLUT also. To explore the effect of MG on the activity of GLUT using a yeast system, we used EBY.S7 carrying a human GLUT1 cDNA and EBY.F4–1 carrying a rat GLUT4 cDNA. Both EBY.S7 and EBY.F4–1 lack all HXT genes (28). We verified the expression of human GLUT1 and rat GLUT4 by Western blotting using anti-GLUT1 and anti-GLUT4 antibodies, respectively (Fig. 6A). In addition, the validity of the function of GLUT1 and GLUT4 expressed in yeast cells was verified by the ability of each transformant to grow in glucose medium, because these hxt null mutants (EBY.S7 and EBY.F4–1) are not able to grow in medium containing glucose as a sole source of carbon (28). As shown in Fig. 6B, glucose uptake in cells carrying human GLUT1 or rat GLUT4 was lowered following treatment with MG in the presence of Lat-B. These results indicate that MG inhibits mammalian glucose transporters.

FIGURE 6.

MG inhibits mammalian GLUTs. A, EBY.S7 (hxtΔ) cells carrying human GLUT1 cDNA were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth, and a membrane fraction was prepared as described under “Materials and Methods.” Expression of GLUT1 cDNA was verified by Western blotting using anti-GLUT1 antibodies. Glucose uptake in the first 5 min in the presence of Lat-B was determined. B, EBY.F4–1 (hxtΔ) cells carrying rat GLUT4 cDNA were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth, and the expression of GLUT4 and glucose uptake were determined as described in A. α-Pma1 indicates the loading control for the membrane fraction.

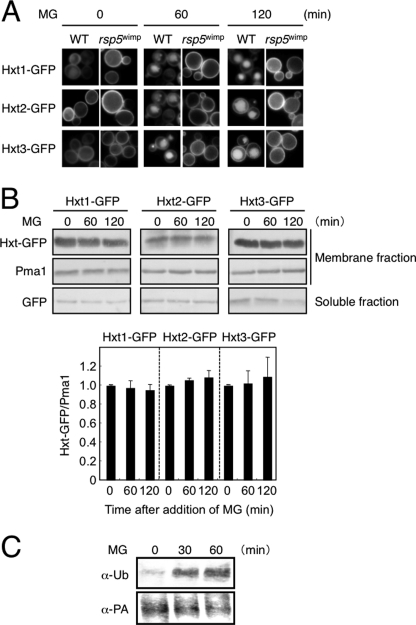

MG-induced Endocytosis of Hxts Is Dependent upon Rsp5

The results obtained led us to conclude that the rapid reduction in glucose uptake following treatment with MG is because of its inhibitory effect on Hxts. Therefore, we next explored the mechanism behind the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts.

Generally, ubiquitination, in many cases mono-ubiquitination, is a trigger for the endocytosis of membrane-integral proteins on the plasma membrane (35). We therefore determined whether ubiquitination of Hxt occurs following treatment with MG. In the ubiquitination of many transporters and permeases on the plasma membrane in S. cerevisiae, Rsp5, a HECT-type ubiquitin ligase, plays an important role (36). To explore whether MG-induced endocytosis of Hxt1–3 is dependent upon Rsp5, we constructed an rsp5wimp mutant. Because the RSP5 gene is essential, an rsp5 null mutant is unavailable. So, we inserted the natMX gene into the promoter of RSP5 to decrease its expression level (22). As shown in Fig. 7A, the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts was inhibited in rsp5wimp cells. We verified that the amounts of Hxt1, Hxt2, and Hxt3 in membrane fractions did not decrease following treatment with MG (Fig. 7B). To verify more directly whether the ubiquitination of Hxt occurs following treatment with MG, we conducted a pulldown experiment with protein A-tagged Hxt2 and IgG beads followed by Western blotting using anti-ubiquitin antibodies. As shown in Fig. 7C, the proportion of Hxt2 having been ubiquitinated was increased following treatment with MG. Taken together, MG induces ubiquitination of Hxts in an Rsp5-dependent manner, and subsequently, endocytosis is induced to degrade them in the vacuole, which leads to a slow and gradual reduction of glucose uptake in the presence of MG.

FIGURE 7.

Hxt is ubiquitinated in an Rsp5-dependent manner. A, cells (YPH250 background) of the wild type (WT) and rsp5wimp carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth and treated with 10 mm MG for the period indicated. The distribution of each GFP-tagged Hxt was observed using a fluorescence microscope. B, rsp5wimp cells (YPH250 background) carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were treated with MG as described in A; soluble and membrane fractions were prepared, and the amount of each GFP protein or Pma1 was determined by Western blotting. The intensity of each Hxt-GFP band in membrane fractions was quantified by densitometry and normalized with Pma1 as a loading control of each lane. The level of each Hxt-GFP protein at 0 min was relatively taken as 1.0. Data are averages for three independent experiments ± S.D. C, MBY242 cells carrying protein A-tagged Hxt2 (HXT2-PA) were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth and treated with MG for the period indicated in the figure. A membrane fraction was prepared by ultracentrifugation. This was followed by a pulldown experiment using IgG beads. Ubiquitination (α-Ub) and the amount of Hxt2-PA (α-PA) were determined using anti-ubiquitin and anti-PA antibodies, respectively, as described under “Materials and Methods.”

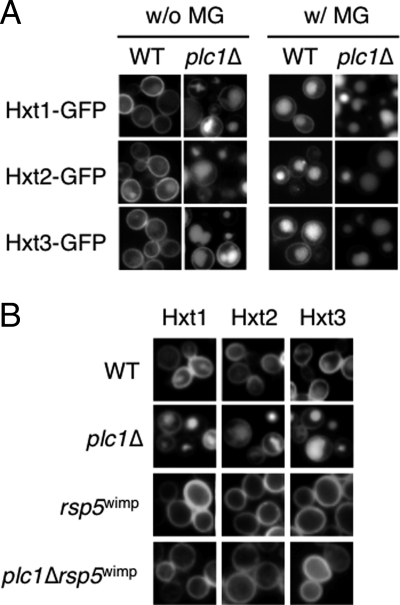

Phospholipase C Negatively Regulates Endocytosis of Hxts

Rsp5 contains the C2 domain that binds to phospholipids, such as phosphatidylinositols. The C2 domain of Rsp5 was verified to bind some species of phosphatidylinositols in vitro (37). Rsp5 has strong affinity for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2), which is distributed in the plasma membrane in yeast cells. Because Hxts are located on the plasma membrane, Rsp5 needs to approach the plasma membrane to interact with its substrates or Hxts. It may be conceivable that Rsp5 associates with the plasma membrane through PtdIns(4,5)P2. PLC1 codes for the sole phospholipase C in S. cerevisiae. Because Plc1 hydrolyzes PtdIns(4,5)P2 (23), it has an ability to bind PtdIns(4,5)P2. To explore the correlation between Rsp5 and Plc1, we investigated the effect of a Plc1 deficiency on the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts. Intriguingly, strong fluorescence derived from Hxt1/2/3-GFPs was observed in vacuoles in plc1Δ cells despite an absence of MG (Fig. 8A). We investigated whether the fluorescence in the vacuoles is due to an increase in the expression of HXTs, thereby inducing the mislocalization of Hxts in vacuoles in plc1Δ cells. We monitored the expression of HXT1–3 using lacZ fusion genes, but we found no distinct differences (data not shown). Next, we constructed a plc1Δrsp5wimp mutant to monitor the localization of Hxt1/2/3-GFPs. As shown in Fig. 8B, GFP-tagged Hxt1–3s are essentially located on the plasma membrane in such a mutant. Therefore, it seems that the deletion of PLC1 causes endocytosis of Hxt1–3 constitutively in an Rsp5-dependent manner. However, Hxt1/2/3-GFPs on the plasma membrane disappeared following treatment with MG (Fig. 8A). These results indicate that the MG-induced endocytosis occurs independently of phospholipase C, although Plc1 can be defined as a negative regulator for endocytosis of Hxts under normal conditions.

FIGURE 8.

Hxts are constitutively internalized in plc1Δ cells. A, plc1Δ cells (YPH250 background) carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth and treated with 10 mm MG for 120 min. The distribution of each GFP-tagged protein was observed using a fluorescence microscope. B, cells (YPH250 background) of the wild type (WT), plc1Δ, rsp5wimp, and plc1Δrsp5wimp carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were cultured in SD medium until a log phase of growth, and the distribution of each GFP-tagged Hxt was determined.

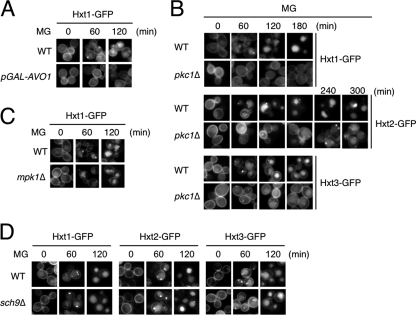

Involvement of TORC2 and Pkc1 in the MG-induced Endocytosis of Hxt

TORC2 is a target of rapamycin kinase complex, consisting of Avo1, Avo2, Avo3, Bit61, and Lst8 (for a review, see Ref. 38). It has been reported that TORC2 is involved in the endocytosis of Ste2, a G protein-coupled α-factor receptor (39). To explore the involvement of TORC2 in the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxt, we used an RL25-1C strain whose AVO1 expression is regulated by the GAL1 promoter (40). Avo1 is an essential component of TORC2 (40). The integrity of TORC2 was maintained when RL25-1C cells were grown in galactose medium, but the unimpaired state was lost after the shift to glucose medium because of the reduced expression of AVO1. As shown in Fig. 9A, endocytosis of Hxt1-GFP did not occur when RL25-1C cells were treated with MG in glucose medium. These results suggest that TORC2 is involved in the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxt.

FIGURE 9.

Involvement of TORC2 and Pkc1 in MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts. A, TB50a (wild type, WT) and RL25-1C (TB50a background with GAL1 promoter-driven AVO1, pGAL-AVO1) cells carrying Hxt1-GFP were cultured in SGal medium until a log phase of growth and transferred to SD medium. After 10 h, 10 mm MG was added, and the distribution of Hxt1-GFP was determined using a fluorescence microscope. B, cells (DL100 background) of the wild type (WT) and pkc1Δ carrying Hxt1-GFP were cultured in SD medium containing 0.5 m sorbitol, and 10 mm MG was added. The distribution of Hxt1/2/3-GFPs was determined using a fluorescence microscope. C, cells (DL100 background) of the wild type (WT) and mpk1Δ carrying Hxt1-GFP were cultured in SD medium containing 0.5 m sorbitol until a log phase of growth, and the distribution of Hxt1-GFP was determined after addition of 10 mm MG. D, cells (YPH250 background) of the wild type (WT) and sch9Δ carrying Hxt1-GFP, Hxt2-GFP, or Hxt3-GFP were treated with 10 mm MG for the period indicated.

In this study, we have demonstrated that MG-induced endocytosis was repressed in the presence of Lat-B, a drug depolymerizing F-actin. TORC2 plays crucial roles in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton (40). Besides TORC2, protein kinase C (Pkc1) is also involved in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton (41). We determined whether Pkc1 is also involved in the MG-induced endocytosis. Although PKC1 is an essential gene, a pkc1Δ mutant is able to grow when sorbitol at high concentrations is supplemented in the medium (41). As shown in Fig. 9B, the MG-induced endocytosis occurred in the presence of sorbitol in wild-type cells. Intriguingly, the timing of the internalization of Hxt1/2/3-GFPs was delayed in pkc1Δ cells following treatment with MG. Pkc1 activates the downstream MAPK cascade consisting of Bck1, Mkk1/Mkk2, and Mpk1, which is also thought to be involved in actin organization (41). However, the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxt1 occurred in mpk1Δ cells with essentially the same timing as that in wild-type cells (Fig. 9C). These results suggest that Pkc1, but not Mpk1 MAPK, is involved in the endocytosis of Hxts in the presence of MG.

DISCUSSION

Inhibition of Hxts by MG

To gain a clue as to the correlation between MG and glucose homeostasis, we determined the effect of MG on glucose uptake using a yeast system. We found that MG inhibits the glucose uptake activity of a yeast hexose transporter (Hxt) and a mammalian GLUT. It is believed that glucose transporters have two glucose-binding sites, one facing the outside of the cell (import site) and the other the inside (export site), and conformational change occurs when glucose binds to either the import site or export site to pass through the transporter (19). Several drugs that inhibit mammalian glucose transporters have been found, many of which are thought to compete with glucose for the glucose-binding sites. For example, cytochalasin B binds to Trp388 and Trp412, both of which are located within the estimated export site of human GLUT1, which leads to the inhibition of glucose uptake (19). By contrast, phloretin, phlorizin, and 4,6-O-ethylidene-d-glucose bind to the estimated import site of GLUT1 (42, 43). Cytochalasin B, phloretin, and phlorizin inhibit the activity of GLUT4 also (44). However, these drugs do not inhibit yeast Hxts.4 Furthermore, as far as we know, no drugs capable of inhibiting yeast Hxts have been found. In that sense, our finding is the first to show a chemical that inhibits yeast Hxts.

It is known that MG reacts with Lys and Arg residues of proteins to form irreversible adducts and reacts with Cys residues reversibly (45). To gain a clue as to the mechanism how MG inhibits Hxt activity, we examined whether inhibition is reversible or not. Cells were treated with MG for 30 min, the timing at which Hxt activity was inhibited by ∼60%, but a large proportion of Hxts has not yet been endocytosed, and subsequently cells were washed to remove MG and transferred to the fresh medium without MG. As shown in Fig. 1C, the levels of glucose uptake were reverted. These results suggest that the inhibitory effect of MG on Hxt activity is reversible. In contrast to mammalian GLUTs, no glucose-binding site has yet been identified in yeast Hxts, so we cannot assign which amino acid residues are the target of MG for inhibition; however, Cys might be one of the candidate amino acid residues to be involved in the MG-dependent inhibition of Hxt. MG may be a useful tool for analyzing the function of Hxts.

We have demonstrated that MG inhibits the activity of not only yeast Hxts but also mammalian GLUT1 and GLUT4. Because MG is an endogenous metabolite, it exists in cells and plasma in mammals, i.e. it can be present both inside and outside of cells. Therefore, MG is accessible to the import site and export site of GLUT. Although the mechanism by which MG inhibits the activity of GLUTs has not yet been identified, our finding that exogenously added MG rapidly inhibits GLUT activity may provide new insights into the glucose homeostasis, which may be linked to diabetes mellitus. One of the pathologies of this disease is sustained hyperglycemia. As MG concentrations in plasma of diabetic patients are higher than those in healthy individuals (11–13), MG may inhibit GLUT1 constitutively expressed on the plasma membrane of many tissues, thereby lowering the efficacy of glucose uptake, which exacerbates the hyperglycemia. In addition, we have shown that MG inhibits GLUT4 also. Mammalian GLUT4 is usually contained in vesicles in cells carrying the insulin receptor. Upon the receipt of insulin, these GLUT4-containing vesicles are translocated to the plasma membrane, and subsequently, GLUT4 is exposed to the cell surface to take up glucose from blood (4). The fact that MG inhibits the activity of GLUT4 implies that MG interferes with insulin-responsive glucose uptake. Hence, the findings of this study using a yeast system lead us to propose that MG is involved in the onset and/or exacerbation of diabetes mellitus through impairment of glucose uptake.

Endocytosis of Hxts by MG

We have demonstrated that Hxt1–3 are ubiquitinated and internalized following treatment with MG and then transported into vacuoles via the MVB pathway for degradation. It has been reported that phosphorylation is preceded by ubiquitination in the endocytosis of many plasma membrane-integral proteins. For example, Ste2 is phosphorylated by casein kinase homologues (Yck1 and Yck2) upon receipt of α-factor (46). Meanwhile, Hog1 phosphorylates Fps1, an aquaglyceroporin involved in the efflux of glycerol and uptake of acetic acid, thereby facilitating its degradation (47). We have previously reported that MG activates Hog1 MAPK (48), so we investigated whether the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxt1/2/3-GFPs is influenced in hog1Δ cells, but we found no distinct differences in endocytosis between wild-type and hog1Δ cells (data not shown).

We revealed that Rsp5 plays a crucial role in the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts. Rsp5 contains a WW domain, through which it is able to interact with the target protein to be ubiquitinated containing the PY motif ((Leu/Pro)-Pro-Xaa-Tyr) (35). Rsp5 functions as the E3 enzyme (ubiquitin ligase) for many transporters and permeases on the plasma membrane, however, it is rare for such cargo proteins to contain a canonical PY motif (35). So, Rsp5 needs to interact with an adaptor protein containing the PY motif that is able to physically interact with cargo proteins. Because Hxts do not contain a PY motif, an adaptor protein or arrestin-related trafficking adaptor (Art) is necessary for Rsp5 to physically interact with Hxts for ubiquitination. Indeed, Art4/Rod1 is involved in the endocytosis of Hxt6 (22). Generally, arrestins are able to bind to the phosphorylated cargo proteins on the plasma membrane (49, 50). Therefore, it is feasible that Hxts are phosphorylated following treatment with MG prior to endocytosis. Hxt7 lacking the cytoplasmic domain at the N terminus was hardly internalized and degraded under conditions where the endocytosis of Hxt7 was induced (high glucose conditions) (51). It has been reported that the PEST (Pro-Glu-Ser-Thr) sequence found at the N terminus of Hxt7 is involved in the degradation (52, 53). Similarly, the PES (Pro-Glu-Ser) sequence found in Hxts and maltose permeases has been also implicated in the degradation process (54). Both PEST and PES motifs contain serine and/or threonine that have the potential to be phosphorylated. Therefore, we tried to detect the phosphorylation of Hxt upon MG stress using protein A-tagged Hxt2 (Hxt2-PA) by pulldown experiments with IgG beads followed by Western blotting using anti-phospho-Ser and anti-phospho-Thr antibodies. However, as far as we could determine, phosphorylation of Hxt2 was not detected (data not shown). Nonetheless, we found that the timing of the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxt1/2/3-GFPs was delayed in pkc1Δ cells (Fig. 9B), so Pkc1 might be a candidate for the protein kinase responsible for the phosphorylation of Hxts for triggering endocytosis.

The endocytosis of Hxts was virtually dependent upon Rsp5. Strikingly, we found that deficiency in Plc1 or Pkc1 affected the endocytosis of Hxts; therefore, both Plc1 and Pkc1 may influence the activity of Rsp5. The constitutive internalization of Hxt1–3 from the plasma membrane in plc1Δ cells was suppressed when the expression of Rsp5 was reduced (Fig. 8B); therefore, Plc1 might repress the function of Rsp5. One possible speculation is that Rsp5 and Plc1 might compete with each other for the binding to PtdIns(4,5)P2 on the plasma membrane. Rsp5 contains the C2 domain. The C2 domain has affinity with PtdIns(4,5)P2, and PtdIns(4,5)P2 is enriched in the plasma membrane. Recently, Kaminska et al. (55) reported that GFP-tagged Rsp5 was located on the plasma membrane. Meanwhile, Plc1 has the pleckstrin homology domain (56), through which it binds to PtdIns(4,5)P2. Therefore, if Plc1 is deleted, Rsp5 may be able to access PtdIns(4,5)P2 more easily, which allows Rsp5 to interact with cargo proteins thereby inducing the constitutive endocytosis of Hxts.

By contrast, because MG-induced endocytosis was delayed in pkc1Δ cells, Pkc1 may be involved in the activation of Rsp5 following treatment with MG. Recently, a cationic amino acid transporter (CTA-1) in HEK293 cells was ubiquitinated by activation of protein kinase C (PKC), which is carried out by Nedd4-1 and Nedd4-2, mammalian orthologues of Rsp5 (57). Therefore, it is conceivable that Pkc1 may activate Rsp5 in yeast cells.

In contrast to Pkc1, Mpk1 MAPK, which lies downstream of Pkc1, was not likely to be involved in the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts (Fig. 9C). Regarding a role of Mpk1 in the endocytosis of Hxts, Soulard et al. (58) have reported that Mpk1 is involved in the rapamycin-induced endocytosis of Hxt1. Rapamycin is a specific inhibitor of TORC1 (target of rapamycin complex 1) (40). We also verified that rapamycin induces endocytosis of Hxt1–3 in an Rsp5-dependent manner using Hxt1/2/3-GFPs (supplemental Fig. S1). Soulard et al. (58) reported that inhibition of TORC1 with rapamycin induces the phosphorylation of Bcy1 at Thr129, by which Bcy1 is activated as a negative regulatory subunit of protein kinase A (PKA). Schmelzle et al. (59) have reported that the rapamycin-induced endocytosis of Hxt1 was suppressed under conditions where the Ras/cAMP pathway was activated, i.e. deletion of BCY1, or introduction of the constitutively activated allele of RAS2 (Ras2Val19). These results imply that PKA negatively regulates endocytosis of Hxt1. Meanwhile, Soulard et al. (58) reported that Sch9, a direct substrate of TORC1, inactivates Mpk1. In addition, they reported that Mpk1 phosphorylates Thr129 of Bcy1 directly in the presence of rapamycin, which leads to deactivation of PKA (58). Collectively, rapamycin treatment deactivates Sch9, which inactivates PKA through the Mpk1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcy1 at Thr129, thereby inducing endocytosis. If MG provokes the same regulatory circuit as rapamycin does, the Mpk1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcy1 might occur, leading to the inhibition of PKA and thereby inducing endocytosis of Hxts. However, we have demonstrated that the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts occurred even in mpk1Δ cells (Fig. 9C). Furthermore, we found that the MG-induced endocytosis of Hxts occurred in sch9Δ cells (Fig. 9D). Taken together, MG and rapamycin seem to induce endocytosis of Hxts via different pathways. Although Pkc1 lies upstream of the Mkp1 MAPK cascade, Pkc1 seems to provoke the endocytosis of Hxts in the presence of MG through a pathway in which Mpk1 is not involved.

Yeast has been used to study many pivotal biological events, because basic mechanistic principals are similar between yeasts and higher eukaryotes. This would also be the case for glucose uptake. The analysis of the intracellular distribution of GLUT1 and GLUT4 in mammalian cells following treatment with MG on the basis of our findings regarding the distribution of yeast Hxts would provide further insight into the correlation between MG and glucose homeostasis as well as diabetes mellitus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. Kasahara (Teikyo University, Japan) for valuable discussions and generous gift of plasmids (Hxt1mnx-pVT, Hxt2mnx-pVT, pVT102-U/His-Xa-human-GLUT1, and pVT102-U/rat-GLUT4) and antibodies (anti-Hxt1, anti-Hxt2, anti-GLUT1, and anti-GLUT4 antibodies); Dr. E. Boles (Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Germany) for EBY.S7 and EBY.F4-1; Dr. K. van Dam (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for KY73; Dr. M. N. Hall (University of Basel, Switzerland) for TB50a and RL25-1C; Dr. A. Breton (CNRS, France) for the Pma1-GFP and Rvs161-GFP plasmids; Dr. D. E. Levin (Boston University) for DL100 and DL376, and Dr. H. R. Pelham (MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, UK) for EN44.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan and grants from Institution of Fermentation, Osaka, Japan (to Y. I.).

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Fig. S1.

T. Kasahara and M. Kasahara, personal communication.

- MG

- methylglyoxal

- Hxt

- hexose transporter

- Lat-B

- latrunculin B

- WCE

- whole cell extract

- MVB

- multivesicular body

- PtdIns(4,5)P2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- TORC2

- target of rapamycin complex 2

- MAP

- mitogen-activated protein

- TORC1

- target of rapamycin complex 1

- GLUT

- glucose transporter.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lagunas R. (1993) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 10, 229–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walmsley A. R., Barrett M. P., Bringaud F., Gould G. W. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 476–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pao S. S., Paulsen I. T., Saier M. H., Jr. (1998) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 1–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang S., Czech M. P. (2007) Cell Metab. 5, 237–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dyer D. G., Blackledge J. A., Katz B. M., Hull C. J., Adkisson H. D., Thorpe S. R., Lyons T. J., Baynes J. W. (1991) Z. Ernahrungswiss 30, 29–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Inoue Y., Kimura A. (1995) Adv. Microb. Physiol. 37, 177–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Inoue Y., Maeta K., Nomura W. (2011) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 278–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kalapos M. P. (1999) Toxicol. Lett. 110, 145–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Turk Z. (2010) Physiol. Res. 59, 147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McLellan A. C., Thornalley P. J., Benn J., Sonksen P. H. (1994) Clin. Sci. 87, 21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beisswenger P. J., Howell S. K., Touchette A. D., Lal S., Szwergold B. S. (1999) Diabetes 48, 198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beisswenger P. J., Howell S. K., O'Dell R. M., Wood M. E., Touchette A. D., Szwergold B. S. (2001) Diabetes Care 24, 726–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lapolla A., Flamini R., Dalla Vedova A., Senesi A., Reitano R., Fedele D., Basso E., Seraglia R., Traldi P. (2003) Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 41, 1166–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yki-Järvinen H., Helve E., Koivisto V. A. (1987) Diabetes 36, 892–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thurmond D. C., Pessin J. E. (2001) Mol. Membr. Biol. 18, 237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mueckler M. (1994) Eur. J. Biochem. 219, 713–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thorens B. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 270, G541–G553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rea S., James D. E. (1997) Diabetes 46, 1667–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uldry M., Thorens B. (2004) Pflugers Arch. 447, 480–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mueckler M., Caruso C., Baldwin S. A., Panico M., Blench I., Morris H. R., Allard W. J., Lienhard G. E., Lodish H. F. (1985) Science 229, 941–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ozcan S., Johnston M. (1999) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 554–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nikko E., Pelham H. R. (2009) Traffic 10, 1856–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flick J. S., Thorner J. (1993) Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 5861–5876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Izawa S., Takemura R., Inoue Y. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35469–35478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roosen J., Engelen K., Marchal K., Mathys J., Griffioen G., Cameroni E., Thevelein J. M., De Virgilio C., De Moor B., Winderickx J. (2005) Mol. Microbiol. 55, 862–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kruckeberg A. L., Ye L., Berden J. A., van Dam K. (1999) Biochem. J. 339, 299–307 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bagnat M., Simons K. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 14183–14188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wieczorke R., Dlugai S., Krampe S., Boles E. (2003) Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 13, 123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ghaemmaghami S., Huh W. K., Bower K., Howson R. W., Belle A., Dephoure N., O'Shea E. K., Weissman J. S. (2003) Nature 425, 737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Katzmann D. J., Odorizzi G., Emr S. D. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 893–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nikko E., André B. (2007) Traffic 8, 566–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kranz A., Kinner A., Kölling R. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 711–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harrison J. C., Bardes E. S., Ohya Y., Lew D. J. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 417–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Engqvist-Goldstein A. E., Drubin D. G. (2003) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 287–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Léon S., Haguenauer-Tsapis R. (2009) Exp. Cell Res. 315, 1574–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rotin D., Staub O., Haguenauer-Tsapis R. (2000) J. Membr. Biol. 176, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dunn R., Klos D. A., Adler A. S., Hicke L. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 165, 135–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Powers T., Aronova S., Niles B. (2010) in The Enzymes (Hall M. N., Tamanoi F., eds) Vol. 27, pp, 177–197, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 39. deHart A. K., Schnell J. D., Allen D. A., Tsai J. Y., Hicke L. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4676–4684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Loewith R., Jacinto E., Wullschleger S., Lorberg A., Crespo J. L., Bonenfant D., Oppliger W., Jenoe P., Hall M. N. (2002) Mol. Cell 10, 457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Levin D. E. (2005) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69, 262–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kasahara T., Kasahara M. (1996) Biochem. J. 315, 177–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mueckler M., Weng W., Kruse M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20533–20538 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kasahara T., Kasahara M. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1324, 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maeta K., Izawa S., Okazaki S., Kuge S., Inoue Y. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 8753–8764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hicke L., Zanolari B., Riezman H. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141, 349–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mollapour M., Piper P. W. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 6446–6456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Maeta K., Izawa S., Inoue Y. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ferguson S. S., Downey W. E., 3rd, Colapietro A. M., Barak L. S., Ménard L., Caron M. G. (1996) Science 271, 363–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lohse M. J., Benovic J. L., Codina J., Caron M. G., Lefkowitz R. J. (1990) Science 248, 1547–1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krampe S., Boles E. (2002) FEBS Lett. 513, 193–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hein C., Springael J. Y., Volland C., Haguenauer-Tsapis R., André B. (1995) Mol. Microbiol. 18, 77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Marchal C., Haguenauer-Tsapis R., Urban-Grimal D. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 314–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brondijk T. H., van der Rest M. E., Pluim D., de Vries Y., Stingl K., Poolman B., Konings W. N. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15352–15357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kaminska J., Spiess M., Stawiecka-Mirota M., Monkaityte R., Haguenauer-Tsapis R., Urban-Grimal D., Winsor B., Zoladek T. (2011) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 90, 1016–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rebecchi M. J., Pentyala S. N. (2000) Physiol. Rev. 80, 1291–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vina-Vilaseca A., Bender-Sigel J., Sorkina T., Closs E. I., Sorkin A. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8697–8706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Soulard A., Cremonesi A., Moes S., Schütz F., Jenö P., Hall M. N. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 3475–3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schmelzle T., Beck T., Martin D. E., Hall M. N. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 338–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Levin D. E., Bartlett-Heubusch E. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 116, 1221–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Balguerie A., Bagnat M., Bonneu M., Aigle M., Breton A. M. (2002) Eukaryot. Cell 1, 1021–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kasahara T., Kasahara M. (2003) Biochem. J. 372, 247–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.