Abstract

Purpose

Garenoxacin, a novel des-F(6)-quinolone, possesses potent antibacterial activity against infectious pathogens in the respiratory tract. Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling and Monte Carlo simulations were used to optimize garenoxacin dosage regimens.

Methods

At the end of phase II stage, the clinical dose of garenoxacin was predicted to be 400 mg once daily by the interim PK/PD analysis using phase I and phase II clinical data. The criteria used to determine an optimal dose were (1) the target attainment of the area under the unbound concentration–time curve divided by the minimum inhibitory concentration (fAUC0−24/MIC ratio) and (2) the maintenance of a trough concentration above the mutant prevention concentration. In a confirmatory phase III study, garenoxacin was administered 400 mg once daily to 136 patients infected with mild or moderate chronic respiratory diseases.

Results

Logistic regression analysis showed that fAUC0−24/MIC ratio was a significant variable that predicted clinical response (p = 0.0164). Of all subjects, 92.4% reached the target value of fAUC0−24/MIC ratio > 30 h, and the clinical efficacy rate of this population was 91.8%. On the other hand, there was no significant relationship between exposure values (AUC0−24 and maximum concentration) and the incidence of adverse events by the Mann–Whitney test.

Conclusions

The antimicrobial efficacy of the actual phase III study was consistent with the expectation from the Monte Carlo PD simulation. We were able to show that the optimal garenoxacin dosage regimens were successfully determined using prospective population PK/PD analysis and clinical trial simulations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1095-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Garenoxacin, Population pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, Monte Carlo simulation, Dose finding, Model-based drug development

Introduction

Garenoxacin is a novel des-F(6)-quinolone antibacterial drug that lacks a fluorine substituent at the C-6 position in the quinolone ring, which had been believed to be indispensable in past fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs. Garenoxacin has a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, including Chlamydia spp., Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Legionella spp. [1, 2]. This drug also shows potent activity against multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae [3], β-lactamase-producing Moraxella catarrhalis [4], and β-lactamase-nonproducing and ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae (BLNAR) [5].

Garenoxacin was approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) in Japan in 2007 for the treatment of pneumonia, secondary infection of chronic respiratory diseases (SICRD), acute bronchitis, sinusitis, otitis media, laryngopharyngitis, and tonsillitis (including peritonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess) (Geninax product insert; Astellas Pharma Inc, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Toyama Chemical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

In the past, dose-finding studies of antimicrobial drugs were based on the pharmacokinetics (PK) in healthy volunteers who participated in a phase I study and the antibacterial activity against clinical isolates, while accounting for the dosage regimen of similar classes of drugs. The validity of the selected candidate dose was subsequently confirmed in a controlled trial using two or more dose levels. However, the conventional dose-finding method is still empirical and lacks a scientific rationale for choosing the most appropriate dose.

The efficacy of the antimicrobial drugs developed in recent years is approximately 90% against respiratory tract infection. Due to these high efficacy rates, it is difficult to decide upon the optimal dose based upon simple comparisons of clinical efficacy and safety profiles at different doses. For example, in a dose-finding study of telithromycin, a ketolide antibiotic, the clinical efficacy of 600 mg once daily and 800 mg once daily against community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) was 92.9 (39/42) and 95.8% (46/48), respectively [6]. In a dose-finding study of doripenem, a carbapenem antibiotic, the clinical efficacy of 250 mg twice daily (b.i.d.) and 500 mg b.i.d. against SICRD were 100 (36/36) and 88.2% (30/34), respectively [7]. No clear relationship between clinical efficacy rate and dose can be observed in such a dose-based clinical trial design.

In terms of the antibacterial action of quinolones, a number of recent studies have clearly shown that the area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) divided by the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (AUC/MIC ratio) is the most important predictive value of clinical and microbiological response. Ambrose et al. reported that the unbound AUC/MIC ratio (fAUC/MIC ratio) was more predictive of outcome than the total AUC/MIC ratio [8]. As the efficacy index for garenoxacin as well as other quinolones, AUC/MIC ratio was deemed appropriate for use in dose finding [9]. In Monte Carlo simulation, the target value of garenoxacin was assumed to be an AUC0−24/MIC ratio of 125 h based on ciprofloxacin data in the report of Forrest et al. [10]. The serum protein binding of garenoxacin was 75% [11], and the AUC0−24/MIC ratio of 125 h was almost equal to the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio of 30 h. This target value was necessary to eradicate bacteria typical of respiratory tract infection (S. pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis) [11, 12].

It has been reported that resistant mutants are selected exclusively within a concentration range (mutant selection window) between the mutant prevention concentration (MPC) and MIC [13, 14]. To restrict resistant mutants, the optimal dose needs to be selected in view of the maintenance of a trough concentration above the MPC. As the MPC of garenoxacin against common bacteria (S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and H. influenzae) is <1 μg/ml, the probability of having a trough concentration >1 μg/ml was computed at several doses.

Population pharmacokinetics (PK) and PK/PD analysis are powerful approaches to investigate exposure–response relationships for both efficacy and safety. Population PK takes into consideration the inter-individual variability in PK parameters of the target patient population, and various infectious bacteria also show various MIC distributions in clinical isolates. The Monte Carlo pharmacodynamic simulation is a computing tool that is used to create an in silico resemblance of the real world and is useful to predict clinical efficacy for assumed doses and dosage regimens [15]. In the study reported here, we applied prospective population PK/PD analysis together with Monte Carlo PD simulation to find and confirm the optimal dose of garenoxacin during drug development in Japan. Our successful experience provides a rational strategy for a learning–confirming paradigm of drug development with the benefits of a shorter time period and a fewer number of trials/patients.

Material and methods

Outline of development strategy

The development of garenoxacin in Japan was achieved by phase I to phase III clinical trials (1999–2005), and this drug was approved in July 2007. The detailed protocol and results of these studies are published elsewhere [16–18]. Briefly, each clinical study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution, and informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation in the specific study. These studies were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice established by the International Conference on Harmonization. The phase I study was conducted in healthy volunteers at doses varying from 100 to 600 mg. The phase II study of garenoxacin 200 or 400 mg once daily for 7–14 days was conducted in patients with respiratory tract infection (CAP and SICRD). The interim population PK model was developed using plasma drug concentration data from subjects who participated in the phase I and II studies. The Monte Carlo PD simulation was performed using the interim population PK parameters and the isolated MIC distribution of the major infectious bacteria. At this stage, the optimal dose was predicted to be 400 mg once daily, based upon (1) the target attainment of the AUC0−24/MIC ratio and (2) the maintenance of a trough concentration above the MPC. In the subsequent phase III study (single-arm, open trial), 400 mg of garenoxacin was given once daily for 10 days to patients with SICRD. The population PK model was revised by adding the phase III data, and PK/PD analyses for efficacy and safety were conducted. The optimal recommended dose of 400 mg once daily was confirmed by comparing the actual results of efficacy in phase III study and Monte Carlo simulations (predictions) at the stage just after the phase II study.

PK data

The plasma garenoxacin concentration data used for the population PK analysis are shown in Table 1 [16–18]. The data from five studies (phase I−III studies conducted in Japan) were utilized for the PK analysis. In each study, after blood was drawn, the plasma was separated and stored at −20°C until measurement. The concentrations of garenoxacin were measured by an assay of validated liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) using an internal standard [19]. The lower limit of quantification was 0.01 μg/ml, and values below this limit were treated as zero for the population PK analysis. A total of 13 measurements from nine subjects were <0.01 μg/ml. The Monte Carlo PD simulation used the interim population PK model developed using 1,396 plasma PK samples (104 subjects) from the phase I and II studies. The final population PK model was obtained using 1,742 plasma PK samples (237 subjects) of phase I−III studies.

Table 1.

Sources of plasma garenoxacin concentration data collected in the Japanese clinical studies

| Study | Subject | Dosage and sampling time | Number of subjects | Number of plasma samplesa | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: single dose | Healthy volunteers | Single-dose administration in a fasted condition. | 24 | 382 | [18] |

| 100, 200, 400, 600 mg | |||||

| Standard PK sampling (16 time points/individual) (0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72 h) | |||||

| Phase I: multiple dose | Healthy volunteers | Multiple dose administration in a fasted condition. | 11 | 502 | [18] |

| 200, 400 mg once daily for 7–14 days | |||||

| Standard PK sampling (42 or 49 time points/individual) (0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72 h) | |||||

| Phase I: food effect | Healthy volunteers | Single dose administration in fasted or fed condition. | 14 | 437 | [18] |

| 400 mg | |||||

| Standard PK sampling (32 time points/individual) (0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72 h) | |||||

| Phase IIb | Patients | Multiple dose administration | 55 | 75 | [16] |

| 200 or 400 mg once daily for 7–14 days | |||||

| Sparse sampling (trough and optional one point/individual) | |||||

| Phase IIIc | Patients | Multiple-dose administration | 133 | 346 | [17] |

| 400 mg once daily for 10 days | |||||

| Sparse sampling [two or four points (trough and peak)/individual] | |||||

| Total | 237 | 1,742 | |||

aThe number of concentrations above the lower limit of quantification (0.01 μg/ml).

bTwo blood samples per individual were collected in 20 patients (36.4%), and one sample was collected in each of 35 patients (63.6%).

cThe number of blood collection points for each patient was four or more in 25 patients (18.8%), three in 33 patients (24.8%), two in 72 patients (54.1%), and one in 3 patients (2.3%).

Determination of MICs

The MIC distributions of the clinically isolated bacteria were determined by the standard agar dilution methods of the Japanese Society of Chemotherapy [20]. The MICs for samples obtained in the phase III study were determined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [21]. The method of the Japanese Society of Chemotherapy used different dilution and medium from the CLSI method. Although the resulting MIC values slightly disagree, these differences were thought to have little influence on the present analysis.

Population PK analysis

The population PK parameters and the objective function value (OBJ) were estimated using NONMEM software [22]. The first-order method in NONMEM version V, level 1.0 was used for both the end of phase II and phase III studies as it was the latest version at the time of decision-making in 2002. Each subject's parameter was calculated by the Bayesian method using the POSTHOC option. Since the first-order method has the limitation that it only yields reasonable results when the between-subject variability is small, we re-estimated the parameters of the final model using the first-order conditional estimation method with interaction by NONMEM version VI, level 2.0.

Structural model development

A linear one-compartment open model with first-order absorption was used as a structural model since the residual error versus time plot was detected as deformation when using the two-compartment model. The parameters of total body clearance (CL/F), distribution volume (V/F), and first-order absorption rate constant (ka) were estimated by using the PREDPP subroutines (ADVAN2 and TRANS2) of the NONMEM program.

Statistical model

The intra-individual (residual) variability was described by a constant coefficient of variation (CV) error model (Eq. 1).

|

1 |

where Cij is the measured plasma concentration value of the j-th subject at i-th time, Cpredij is the predicted plasma concentration value of the j-th subject at i-th time, and εij is a random variable with a mean of zero and a variance of σ2.

The inter-individual variability for the PK parameter was assumed by a log-normal distribution (Eq. 2).

|

2 |

where Pj is parameter value of the j-th subject, P is the estimated population mean, and ηj is a random variable with a mean of zero and a variance of ω2.

Covariate model

Typical functional forms used for covariate analysis included linear, power, and additive shift of these forms (eqs. 3, 4 and 5).

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

5 |

where Xj is the estimated typical parameter value in the j-th subject, covj is the measured value of a particular covariate in the j-th subject, cov is the arithmetic mean value of the covariate in the population, and θintx and θcovx are estimates of the population mean.

The covariates were searched by forward selection and confirmed in the final model by the backward elimination. The model selection was conducted based on visual inspection of the scatter plot of individual PK parameters versus covariate values and the likelihood ratio test (α = 0.05). The demographic characteristics examined were age, gender, body weight (BW), ideal body weight (IBW), and degree of obesity (obese patient: BW/IBW > 1.3) [11]. The laboratory data examined were those of total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and creatinine clearance (CLCR). Creatinine clearance was calculated by the Cockcroft–Gault equation [23]. Since no effect of food on CL/F or ka was detected in the phase I food effect study [18], the effect of food was excluded from the covariate analysis.

Assessment of model uncertainty

The final model examined stability and robustness using the bootstrap method [24]. One thousand non-stratified bootstrap datasets of garenoxacin were generated using plasma samples from the five studies (phase I−III studies). The parameters were estimated using the final model for these datasets. The median and 5–95% percentile was calculated for 1,000 sets of these parameters and compared with the parameters calculated from the original dataset. When the parameter values of both datasets nearly corresponded, the robustness of the model was confirmed.

Monte Carlo simulation

The MIC distributions of clinical isolates collected from 1994 to 1997 in Japan were used for the Monte Carlo simulation analysis (Table 2) because these were the only available MIC data at the time of the simulation. The major species of pathogens were selected from drug-susceptible and drug-resistant bacteria commonly found in community-acquired respiratory tract infections. In addition, the garenoxacin MIC distributions of clinical isolates collected during 1994–1997 [2] were almost similar to those collected during 2000–2005 (during the present clinical trials) [5]; therefore, these data were considered suitable for the simulation.

Table 2.

Subject characteristics in the population pharmacokinetic analysis

| Characteristics | Clinical isolates from Japanese patients | End of phase II stage (interim analysis) | Phase III data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diseasea | – | CAP, SICRD | SICRD |

| Number of subjects (n) | – | 104 | 133 |

| Healthy subjects/Infected patients (n) | – | 49/55 | – |

| Males/females (n) | – | 77/27 | 87/46 |

| Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | Mean ± SD (Min–Max) | ||

| Age (year) | – | 40.0 ± 20.4 (20–74) | 66.3 ± 14.8 (19–94) |

| Body weight (kg) | – | 58.5 ± 10.4 (34–83) | 52.7 ± 13.0 (33–120) |

| CLCR (ml/min) b | – | 102.4 ± 29.7 (34.4–178.7) | 71.1 ± 29.4 (19.3–199.2) |

| Pathogens | MIC90 (Min–Max) [n]c | MIC range [n]d | MIC range [n]e |

| Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) | 0.025 (0.0125–0.05) [23] | ≤0.025 [2] | ≤0.06–0.25 [8] |

| Penicillin-sensitive strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae (PSSP) | 0.05 (0.025–0.05) [24] | 0.10 [3] | ≤0.06–0.25 [6] |

| Penicillin intermediately or highly resistant strains of S. pneumoniae (PISP/PRSP) | 0.05 (0.025–0.05) [23] | 0.05 [1] | ≤0.06 [8] |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 0.0125 (0.00313–0.0125) [50] | ≤0.025 [10] | ≤0.06–0.5 [29] |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 0.10 (≤ 0.00625–0.39) [50] | ≤0.025 [1] | ≤0.06 [7] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 3.13 (0.05–25) [54] | – | 0.12–0.5 [4] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | > 100 (0.78– > 100) [35] | 0.20–0.78 [2] | 0.12–32 [5] |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | – | – | 0.05 [1] |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae | – | – | 0.20–3.13 [2] |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | – | – | 0.39 [1] |

aCAP, Community-acquired pneumonia; SICRD, secondary infection of chronic respiratory diseases

bCreatinine clearance (CLCR) was calculated by the Cockcroft-Gault equation. Male: CLCR (ml/min) = ([140 – age (years)] × WT (weight, kg)/[72 × serum creatinine (SCr, mg/dl)]. Female: CLCR (ml/min) = ([140 – age (years)] × WT (kg)/[72 × SCr (mg/dl)] × 0.85

cThe pathogens were clinically isolated from Japanese patients during 1994–1997. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) required to inhibit the growth of 90% of organisms (MIC90) was determined by standard agar methods of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. Other pathogens were: ciprofloxacin (CIP)-susceptible methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with a MIC of 0.025 (0.0125–0.05) (n = 51), CIP-resistant MRSA 6.25 (0.10–6.25) (n = 26), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) 3.13 (≤ 0.05–3.13) (n = 24)

dThe pathogens were isolated from 26 patients of the phase II study. The MICs were determined by standard agar methods of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. Other pathogens were: S. intermedius with a MIC of 0.05 (n = 1), S. constellatus 0.10 (n = 1), K. oxytoca 0.05, 0.10 (n = 2), M. pneumoniae 0.015 (n = 2), and K. pneumoniae whose MIC was not measured (n = 1)

eThe pathogens were isolated from 66 patients who participated in the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) analysis of the phase III study. The MICs were determined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)

The population PK model parameters obtained in the interim analysis at the end of phase II stage were used for simulation, and the population PK model equation of Model 2 (Table 3) was used. The virtual PK/PD data for 10,000 cases were generated by SAS software (ver. 8.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The distribution of AUC0−24 in the steady state was calculated by Model 2, including CLCR, in which CLCR determined by the Cockcroft–Gault equation was randomly sampled from the observed distribution of the patients’ real values in the phase II study (Table 2; 34.4−133.2 ml/min, n = 55). The target value of 30 h for the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio was assumed for S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis, which are the major pathogens of community-acquired respiratory tract infection [11, 12].

Table 3.

Development of population PK model for garenoxacin

| Model no. | Model construction a | CV ω2CL/F | CV ω2Vd/F | OBJ (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| End of phase II stage (interim analysis)b | ||||

| 1 | Base model | 19.4% | 18.3% | 356.754 |

| 2 | CL/F = θ1 + θ2 × (CLCR − 85) | 20.6% | 21.0% | 271.509 (p < 0.001) |

| End of phase III stage (final analysis)c | ||||

| 1 | Base model | 37.4% | 37.0% | 1475.267 |

| 2 | CL/F = θ1 + θ2 × (CLCR − 85) | 19.5% | 32.4% | 1403.379 (p < 0.001) |

| V/F = θ3 | ||||

| 3 | CL/F = θ1 + θ2 × (CLCR − 85) | 20.6% | 16.4% | 1309.516 (p < 0.001) |

| V/F = θ3 × (WT/55) θ4 | ||||

| 4 | CL/F = θ1 + θ2 × (CLCR − 85) | 20.6% | 16.4% | 1298.040 (p < 0.001) |

| V/F = θ3 × (WT/55) θ4 + θ5 × GEN | ||||

| 5 (final model) | CL/F = θ1 + θ2 × (CLCR − 85) + θ3 × (WT − 55) | 20.1% | 15.8% | 1292.110 (p = 0.015) |

| V/F = θ4 × (WT/55) θ5 + θ6 × GEN | ||||

CV, Coefficient of variance; OBJ, objective function value

aCL/F, Total body clearance; V/F, distribution volume/F; GEN, gender (1: male; 0: female); θ, population mean parameters

bFirst-order method (NONMEM version V, level 1.0)

cFirst-order conditional estimation method with interaction (NONMEM version VI, level 2.0)

The probability of a trough concentration above the target value of MPC (1 μg/ml) at various doses was calculated using Model 2 including CLCR, and the virtual data for 1,000 cases were generated by SAS software (ver. 8.2). The MPCs against S. pneumoniae (penicillin-sensitive, -intermediately sensitive, and highly resistant strains of S. pneumoniae [PSSP, PISP, and PRSP, respectively)], ciprofloxacin (CIP)-susceptible MSSA, and H. influenzae have been reported to be <1 μg/ml [5, 25, 26].

Phase III study (PK/PD study)

Japanese patients diagnosed with mild or moderate SICRD [acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis (AECB), diffuse panbronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis, bronchial asthma, and old pulmonary tuberculosis] were targeted [17]. For this study, outpatients or inpatients who were 18 years of age or older were eligible. For participation in the study, patients had to demonstrate the following four conditions: production of purulent or mucopurulent sputum; increased level of C-reactive protein (CRP; ≥0.7 mg/dl); fever (>37.0°C); leukocytosis (≥8,000/mm3). Patients were also required to meet at least two of the following criteria: increased cough, dyspnea, or an increase in sputum volume. In this study, 400 mg of garenoxacin was administered once daily for 10 days. The clinical efficacy was evaluated 7–14 days after the initiation of treatment. The blood collection points and timing were set by examining the capability of the parameter estimation using simulated drug concentration data. The blood collection schedule assumed the following four cases: Case 1 included four points with two peaks and two troughs; Case 2 included two points with one peak and one trough; Case 3 included three points with two peaks and one trough; Case 4 included two points with two troughs. Individual estimation of both CL/F and V/F was possible for Cases 1–3, but not for Case 4. Therefore, the blood collection schedule in the phase III study was designed to include two to four points per individual with peaks and troughs.

PK/PD analysis in the phase III study

PK/PD analysis of efficacy

The AUC0−24 was calculated for each patient using the final population PK model. The measured MIC and AUC0−24 from patients in whom the infecting organism had been detected were used to calculate the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio for these patients. When two or more infecting bacteria were detected in a patient, the higher MIC was used. It is noted that the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio is widely used as a no-dimension parameter in the field of antimicrobial agents [27]. This article attaches the unit of time (h) since the units of fAUC0−24 are mass/volume × time, and the units of MIC are mass/volume; therefore, the unit of the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio is time (h). The relationship between fAUC0−24/MIC ratio and clinical response was analyzed by logistic regression analysis. For the analysis of probability of cure, the logistic regression model was used with the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio, in which cure and failure were coded as 1 and 0, respectively. The fAUC0−24/MIC ratio was also divided into a categorical variable by the upper or lower limit of the target value. The values were explored using classification and regression tree (CART) analysis with SPSS software (ver. 14).

PK/Safety analysis

The relation between drug exposure values [AUC0−24 or peak concentration Cmax)] and the incidence of adverse events was analyzed. The adverse events during the study were assessed on the basis of all accompanying symptoms and laboratory test data. The patients were divided into two groups on the basis of whether an adverse event occurred, and the drug exposure values (AUC0−24 and Cmax) distributions of each group were calculated. The Mann–Whitney test was applied to assess any relationship between drug exposure values and incidences of adverse events. The level of two-tailed significance in the verification was set at 5%.

Results

Plasma samples

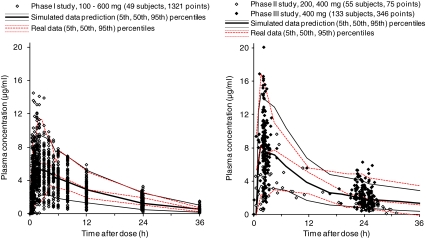

The population PK analysis reported here used the plasma concentration data obtained from five clinical studies (phase I−III studies) conducted in Japan (Table 1). No data were excluded as outliers. The plasma garenoxacin concentration–time profile and visual predictive check by the final model is shown in Fig. 1. The plot of median values locates to the center of distribution of the data points; Fig. 1 also plots the area between the 5th and 95th percentiles of simulated data prediction, an area which is similar to that created by the 5th to 95th percentiles of the real data. The 5th percentile of the observed values from healthy volunteers (left panel) was slightly higher than the simulated data using the final model, probably due to the smaller variability. It is noted that the data from phase II (open circles) corresponded to the 200 mg and 400 mg doses, which give the impression that these data show a lower distribution when compared with those of phase III (400 mg dose only). There was no pronounced difference in the distributions of observed values for the 400 mg dose between phase II and phase III studies, and the population characteristics were similar, with the exception of a wider individual variability in age in the phase III study.

Fig. 1.

Plasma garenoxacin concentration versus time profile. Plotted symbols show the observed concentration data, and the lines show the results of visual predictive checks. For simulated data, the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles (from bottom to top) of the final model simulated data are displayed; for real data, the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles (from bottom to top) of the observed concentrations are displayed. These percentiles were set for the 400 mg dose, which is clinical standard dose

Phase I studies were conducted as three studies; a total of 1,321 plasma samples were collected from 49 subjects. For the phase II study, 62 patients with respiratory tract infection participated (36 with CAP and 26 with SICRD). A total of 41 plasma samples were obtained from 28 patients receiving 200 mg garenoxacin once daily, and 34 plasma samples were obtained from 27 patients receiving 400 mg garenoxacin once daily. For the phase III study, the 346 plasma garenoxacin concentrations were obtained from 133 of 136 patients with SICRD.

Subject characteristics

The characteristics of the subjects who participated in the population PK analysis are shown in Table 2. Interim population PK analysis was performed on data from 55 patients and 49 healthy volunteers. The final analysis of the phase III data addition covered 188 patients and 49 healthy volunteers. The patient characteristics from only the phase II study (shown as mean ± standard deviation) were: age, 55.4 ±16.6 years; body weight, 54.9 ± 11.2 kg; CLCR, 84.6 ± 24.8 ml/min. Their characteristics were similar to those in the phase III study. These studies involved CAP and SICRD because they are respiratory tract infections targeted by quinolone.

Development of the population PK model

The process for reaching the final model is shown in Table 3. A linear one-compartment open model with first-order absorption was conducted as the base model (Model 1). In the first covariate examination, a linear relationship was observed between CLCR and CL/F (Model 2). Model 2 was selected as the interim population PK model and then used for the Monte Carlo simulations. Other covariates were investigated further in the final analysis. A power relationship was obtained between body weight and V/F (Model 3). Moreover, an additive shift was found between gender and V/F (Model 4). Also, a linear relationship was shown between body weight and CL/F (Model 5). Model 5 was selected as the final population PK model.

Population PK parameters of the final model

Table 4 shows the population PK interim and final models. The parameter estimates of the interim Model 2 and the final model showed similar values. In the final model, the same covariates were selected for both the first-order method of NONMEM ver. V (not displayed) and the first-order conditional estimation method with the interaction of NONMEM ver. VI. The model was validated through the visual predictive check method (Fig. 1). Diagnostic plots showed a slight discrepancy between the observed values and the population mean predictions, but the prediction was improved for individual estimates by the Bayesian method (Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 1). These correlation coefficients (r value) were 0.831 for populations and 0.896 for individuals. The final PK parameters were well estimated with small standard errors. Estimates of the shrinkage for CL/F, V/F, and ka were 0.226, 0.295 and 0.573, respectively, suggesting that the individual estimates for CL/F and V/F were reasonably robust and that the individual estimates of ka were subjected to shrinkage and therefore less reliable.

Table 4.

Final population pharmacokinetics parameters for garenoxacin

| Parameter | End of phase II stagea | End of phase III stageb | Bootstrap (n =1,000)c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | Final model | ||||

| CL/F (ml/min) CL/F = θ1 + θ2 × (CLCR − 102) | CL/F = θ1 + θ2 × (CLCR − 85) + θ3 × (WT − 55) | ||||

| θ1 | 66.7 ± 1.7 | 64.3 ± 1.25 | 65.3 (62.2 –76.3) | ||

| θ2 | 0.167 ± 0.036 | 0.213 ± 0.0309 | 0.184 (0.109 –0.261) | ||

| θ3 | − | 0.276 ± 0.113 | 0.328 (0.090–0.540) | ||

| V/F (l) V/F = θ4 | V/F = θ4× (WT/55) θ5 + θ6 × GEN | ||||

| θ4 | 61.8 ± 1.7 | 53.9 ± 1.89 | 55.4 (49.8–68.4) | ||

| θ5 | − | 0.739 ± 0.104 | 0.502 (0.195 –0.873) | ||

| θ6 | − | 6.98 ± 1.88 | 8.02 (3.85–10.56) | ||

| ka (1/h) | 4.72 ± 0.54 | 2.14 ± 0.223 | 2.16 (1.69–2.99) | ||

| Coefficent of variance | Coefficient of variance | ||||

| Inter-individual variability | Inter-individual variability | ||||

| ωCL/F 2 | 0.0424 ± 0.0097 | 20.6% | 0.0403 ± 0.00748 | 20.1% | 0.0374 (0.0149–0.0673) |

| ωV/F 2 | 0.0443 ± 0.0132 | 21.0% | 0.0249 ± 0.00585 | 15.8% | 0.156 (0.0181–0.3915) |

| ωCL/F,V/F | 0.0330 ± 0.0115 | 0.0292 ± 0.00618 | 0.0096 (0.0036–0.0385) | ||

| (r d = 0.761) | (r = 0.922) | ||||

| ω2ka | 2.63 ± 0.56 | 162% | 0.411 ± 0.0863 | 64.1% | 0.470 (0.269–1.073) |

| Intra-individual variability | Intra-individual variability | ||||

| σ2 | 0.0645 ± 0.0057 | 25.4% | 0.105 ± 0.0060 | 32.4% | 0.113 (0.095–0.162) |

ka, First-order absorption rate constant

aFirst-order method (NONMEM version V, level 1.0). Data are presented as the estimated value ± standard error

bFirst-order conditional estimation method with interaction (NONMEM version VI, level 2.0). Data are presented as the estimated value ± standard error

cData presented as median, with the 5−95% percentiles in parenthesis

d r, Correlation coefficient

The uncertainty of the parameters was assessed by a non-stratified bootstrap method with 1,000 replications. The NONMEM software program was performed using the simulated data and repeating the simulation by the bootstrap re-sampling 1,000 times. All 1,000 estimation replications converged successfully. The average values of the estimated parameters by the bootstrap method resembled the final estimates of the population PK parameters (Table 4).

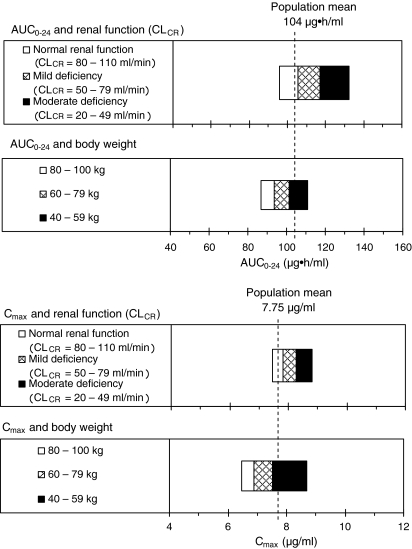

Influence of the covariate on AUC0−24 and Cmax

The influence of the covariates (renal function, body weight) on AUC0−24 and Cmax are shown in Fig. 2. In the relationship between CLCR (renal function) and AUC0−24, when CLCR values were normal (80–110 ml/min) or showed mild renal impairment (50–79 ml/min) or moderate renal impairment (20–49 ml/min), the corresponding AUC0−24 values were 96–105, 105–117 and 117–132 μg·h/ml, respectively. A negative relation was seen for CLCR and AUC0−24. When there was a moderate impairment of renal function, the AUC0−24 increased by about 1.3-fold compared to normal function. An inverse relation was found between CLCR and Cmax. The Cmax increased about 1.1-fold when the CLCR indicated moderate renal impairment. In a comparison by body weight between a 100-kg patient and 60-kg patient, the AUC0−24 and Cmax decreased by 0.86-fold, showing an inverse relation between the parameters and body weight.

Fig. 2.

Influence of the covariates (renal function and body weight) on the plasma concentration–time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC 0−24) and peak plasma concentration (C max). Exposure values (AUC0−24 and Cmax) were simulated by the population mean parameters of the final model using the characteristics of 237 subjects. The simulation was made by varying one covariate within the particular range while all other covariates were kept at their mean value. CL CR Creatinine clearance

Prediction of clinical efficacy by Monte Carlo simulation

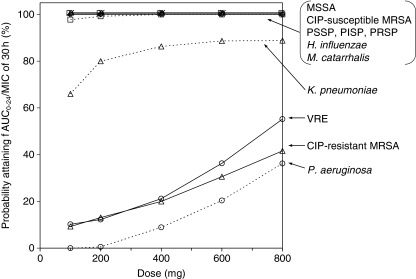

The infecting bacteria isolated from patients with CAP in Japan mainly consisted of S. aureus [methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MSSA, MRSA, respectively)], S. pneumoniae (PSSP, PISP, and PRSP), H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, and K. pneumoniae [28]. The probability for the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio of each infecting organism to exceed 30 h (estimated by Monte Carlo simulation) is shown in Fig. 3. With a dose of ≥100 mg, the probability of 100% attainment could be expected for MSSA, CIP-susceptible MRSA, PSSP, PISP, PRSP, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis. With a dose of 100 or 200 mg, the probability of 75−80% attainment could be expected for K. pneumoniae, while the attainment probability reached a plateau (90%) at ≥400 mg. For vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), CIP-resistant MRSA, and P. aeruginosa, the probability of target attainment was only 10−30% at 400 and 600 mg.

Fig. 3.

Monte Carlo simulation for reaching the target attainment [unbound AUC/minimum inhibitory concentration ratio (fAUC0−24/MIC) > 30 h] with various doses. Steady-state AUC0−24 was calculated using the interim population pharmacokinetics parameters of Model 2 in Table 3. The creatinine clearance was randomly simulated from the observed distribution of the patients real values (34.4−133.2 ml/min, n = 55). The AUC0−24 and MIC values were simulated for 10,000 putative cases to generate the fAUC0−24/MIC distribution for each pathogen. MSSA, MRSA Methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, PSSP, PISP, PRSP penicillin-sensitive, intermediately resistant, and highly resistance, respectively, strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae, VRE vancomycin-resistant enterococci, CIP ciprofloxacin

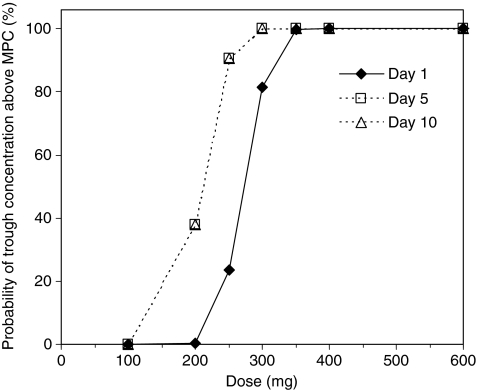

The probability for a trough garenoxacin concentration above the MPC (1 μg/ml) against S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae is shown in Fig. 4. The plasma concentration was expected to exceed the MPC during the 400 mg treatment. The probability at 300 mg on Day 1 was 81.4%, but increased to 100% on Days 5 and 10. The 200 mg dose was insufficient to exceed the MPC. Therefore, a dose of 400 mg once daily was regarded as an optimal clinical dose for the phase III study from two Monte Carlo simulations.

Fig. 4.

Monte Carlo simulation for reaching target mutant prevention concentration (MPC; 1 μg/ml) with various doses. Trough concentration was calculated using the interim population pharmacokinetics parameters of Model 2 in Table 3 and patient covariates randomly re-sampled from real CLCR values (34.4–133.2 ml/min, n = 55). Trough concentration was simulated for 1,000 putative cases, and the probability of reaching above MPC was calculated for various garenoxacin dosing regimens (doses of 100, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400, and 600 mg). The typical MPC value was <1 μg/ml for S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae, including resistant strains

Summary of the phase III study population

The plasma garenoxacin concentrations from 133 of 136 patients were used for population PK and PK/safety analyses. The 66 patients with isolated causative organism of SICRD and its respective MIC value were used for PK/PD analysis of the efficacy. Of the 133 patients, 87 patients were men (65.4%), the mean age was 66.3 years (range 19–94 years), and the mean body weight was 52.7 kg (range 33–120 kg). The clinical observation for the efficacy was 83.7% (103/123) [17], and the clinical efficacy rate in the PK/PD analysis population was 87.9% (58/66). The incidence rate of all adverse events, including abnormal changes in laboratory test results, was 62.5% (85/136).

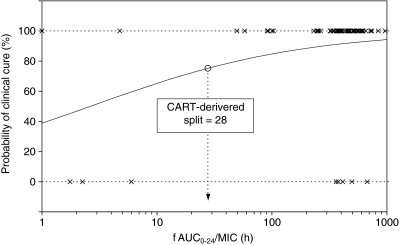

PK/PD analysis for efficacy

The efficacy predicted by the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio in the phase III study is shown in Table 5. Of all subjects, 92.4% (61/66) reached the target value of an fAUC0−24/MIC ratio > 30 h, and the clinical efficacy rate of this population was 91.8% (56/61). The logistic regression analyses of the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio and efficacy are shown in Table 6 and Fig. 5. The analysis demonstrated that the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio was a significant factor affecting clinical response (p = 0.0164), and a sigmoid response curve was seen between the efficacy probabilities and log fAUC0−24/MIC ratio. In addition, the target value for fAUC0−24/MIC was determined by CART analysis, and an fAUC0−24/MIC ratio > 28 h was found to be a statistically significant (p = 0.0059) predictor of clinical success.

Table 5.

Clinical efficacy rates stratified by fAUC0−24/MIC obtained at the phase III study

| fAUC0−24/MIC (h) | Efficacy rate (cure/number of patients) | 95% confidence interval for efficacy rate |

|---|---|---|

| >30 | 91.8% (56/61) | 81.9 –97.3% |

| ≤30 | 40.0% (2/5) | 5.3– 85.3% |

| >28 a | 91.8% (56/61) | 81.9 –97.3% |

| ≤28 | 40.0% (2/5) | 5.3– 85.3% |

fAUC0−24/MIC, Unbound AUC/minimum inhibitory dose ratio

aClassification and regression tree (CART)-derived split

Table 6.

Results of logistic regression analysis of fAUC0-24/MIC affecting the probability of clinical cure by garenoxacin (n = 66, phase III data)

| Variable | Coefficient (β) | Standard error | Wald χ2 | p value | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression analysis by continuous valuea | |||||

| Intercept | −0.4565 | 1.0317 | − | − | − |

| fAUC0−24/MIC | 1.0865 | 0.4526 | 5.76 | 0.0164 | 2.964 |

| Logistic regression analysis by categorical valueb | |||||

| Intercept | −0.4055 | 0.9129 | − | − | − |

| fAUC0−24/MIC > 28 h | 2.8214 | 1.0253 | 7.57 | 0.0059 | 16.80 |

fAUC0−24/MIC > 28 h and fAUC0−24/MIC ≤ 28 h were coded as 1 and 0, respectively

aThis value was transformed (common logarithmic transformation)

bVariable was categorized by CART-derived breakpoint

Fig. 5.

Logistic regression analysis of efficacy against all pathogens for the relationship between log fAUC0−24/MIC and clinical efficacy rate. Circles Split for fAUC0−24/MIC of garenoxacin as determined by the classification and regression tree (CART) analysis

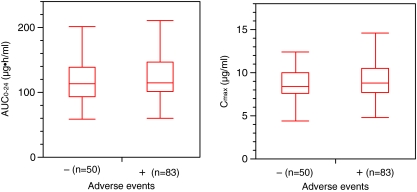

PK/PD analysis for safety

A relation between drug exposure values and the incidence rate of adverse events was examined by the Mann–Whitney test (Fig. 6). No statistically significant difference in AUC0-24 and Cmax was found between the adverse event and non-adverse event groups.

Fig. 6.

Relationships between drug exposure values and the incidence of adverse events in 133 patients. AUC0−24 (left panel) and Cmax (right panel) of garenoxacin were obtained from each subject who received 400 mg dose

Comparison of Monte Carlo simulation and the phase III study results

The probability for attainment of the target fAUC0−24/MIC ratio estimated by Monte Carlo simulation was consistent with the actual efficacy of the phase III study for each strain (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparison between expectation by the Monte Carlo simulation and the observed results in the phase III study

| Pathogens | Monte Carlo simulation at the end of phase II stage | Phase III study | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fAUC0−24/MIC, h [median (5–95% percentiles)] | Target attainmenta (%) | Efficacy rateb | Bacterial eradication ratec | |

| MSSA | 1097 (650–2225) | 100 | 7/8 | 6/8 |

| PSSP | 690 (372–1454) | 100 | 6/6 | 5/5 |

| PISP, PRSP | 774 (375–1482) | 100 | 7/8 | 8/8 |

| H. influenzae | 3479 (1494–9259) | 100 | 28/29 | 26/27 |

| M. catarrhalis | 1227 (231–4895) | 100 | 6/7 | 6/6 |

| K. pneumoniae | 188 (4–493) | 87 | 3/4 | 2/4 |

| P. aeruginosa | 11 (0–36) | 6 | 2/5 | 1/5 |

a Probability that fAUC0−24/MIC exceeds 30 h

b Efficacy rate: patients who were cured / number of patients

c Bacterial eradication rate: patients with pathogen eradicated/number of patients with pathogen. Data were missing for four patients

Discussion

During the development of antibacterial drugs, it is necessary to consider various factors, such as antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetics, clinical efficacy, patient characteristics, safety, and the prevention of the emergence of bacterial resistance, among other, when setting the clinical dose [29, 30]. Previously, an optimal dose of antimicrobial agents was determined based on clinical trials using randomization and double-blind studies at various doses. However, using such study designs, it was difficult to obtain a dose–efficacy correlation in most cases and, subsequently, to find the optimal dose for clinical efficacy.

Efficacy of quinolones generally shows a correlation with the AUC/MIC ratio, and the efficacy of garenoxacin also showed a strong correlation with the AUC0−24/MIC ratio in the preclinical study [12]. Therefore, we determined the optimal dose using the following strategy (1) The AUC0−24/MIC ratio would be the most relevant PD measurement for in vivo efficacy; (2) Monte Carlo simulations with the population PK parameters combining the MIC distribution and MPC of the most common infecting bacteria were used to predict a recommended dose through the probability of target attainment; (3) the validity of an estimated recommended dose by Monte Carlo simulation was confirmed by PK/PD results in actual phase III study for respiratory tract infection.

When the Monte Carlo simulation is applied to predict an optimal dose of fluoroquinolones, the target value of AUC0−24/MIC ratio against causative bacteria is important as a surrogate indicator of clinical and microbiological effectiveness. At first, the target value of garenoxacin was assumed to be an AUC/MIC ratio of 125 h. The fAUC0−24/MIC ratio is known to be a better predictor than the total AUC0−24/MIC ratio [8, 12]. The serum protein binding of garenoxacin is 75% [11], and the AUC0−24/MIC ratio of 125 h is almost equal to the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio of 30 h. Andes et al. reported that in a mouse infection model using garenoxacin, the mean ± standard deviation of fAUC0−24/MIC for S. pneumoniae was 32.5 ± 18 h and that for the most common causative bacteria (including S. aureus, K. pneumonia) was 33.2 ± 30 h [12]. Moreover, in an analysis of clinical trials targeting mild–moderate CAP, acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis and sinusitis, Van Wart et al. [11] reported that a garenoxacin dosing target of fAUC0−24/MIC > 30 h was necessary to eradicate typical bacteria of respiratory infections (H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, and M. catarrhalis). From these results, when targeting the mild–moderate respiratory infections, it seemed appropriate to set a target value of fAUC0−24/MIC > 30 h (equivalent to AUC0−24/MIC > 125 h) for the bacteria of respiratory tract infection. Therefore, in our analysis, the target fAUC0−24/MIC ratio was assumed to be 30 h for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. However, it has been reported that a fAUC0−24/MIC ratio of 70–90 h is required for Gram-negative bacteria, which is higher than the target for Gram-positive bacteria [8]. This may be another reason for conducting the Monte Carlo simulation.

As a result of the actual PK/PD analysis in the phase III study, logistic regression analysis showed that the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio was a significant variable associated with clinical response (Fig. 5). The split value of fAUC0−24/MIC = 28 h was identified by CART analysis. This split value is similar to the target value of fAUC0−24/MIC = 30 h and, therefore, the validity of a target value of 30 h was confirmed by this analysis (Table 6; Fig. 5).

The optimal dose was predicted by Monte Carlo simulation at the end of a phase II study using the interim population PK model. The model was constructed using data from phase I studies of healthy volunteers and phase II studies of infected patients (Table 3). Since no significant difference in population means and inter-individual variability of clearance was observed between healthy volunteers and patient groups, the model was developed by pooling data from 55 patients and 49 healthy volunteers.

The optimal dose of garenoxacin was considered from two viewpoints by two Monte Carlo simulations. One is the relationship between dose and efficacy predicted within a dose range from 100 to 800 mg (Fig. 3). The clinical effect was assumed to be associated with the probability of attaining a fAUC0−24/MIC of 30 h. Garenoxacin was expected to possess antimicrobial activity against MSSA, PSSP, H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, K. pneumoniae, and resistant bacteria of CIP-susceptible MRSA, PISP, and PRSP. On the other hand, garenoxacin was not expected to be effective against P. aeruginosa and VRE.

The other viewpoint was that the MPC concept combined with PK profiles could be useful for optimizing the dosing regimen to prevent the emergence of resistant mutants [31]. Attainment of a plasma concentration above the MPC was considered to be essential when determining the dose necessary to prevent the emergence of resistance. The MPC of garenoxacin was 0.5 μg/ml for S. pneumoniae, 0.4 μg/ml for S. aureus, and 0.06 μg/ml for H. influenzae [25, 26, 32] and, therefore, was considered to be <1 μg/ml against the common bacteria. The probability of a trough concentration >1 μg/ml was computed at several doses. The trough concentration of the 400 mg dose exceeded 1 μg/ml from Day 1 (Fig. 4). Homma et al., under conditions using the time–concentration curves observed by oral administration of moxifloxacin (400 or 80 mg, once a day) or levofloxacin (200 mg, twice a day) and with an in vitro PD model, reported that the levofloxacin- and moxifloxacin-resistant S. pneumoniae mutants did not emerge when the fAUC0−24/MPC was ≥13.4 h and unbound peak concentration (fCmax)/MPC was ≥1.20 [33]. In our study, the Cmax of garenoxacin given at a dose of 400 mg was 7−8 μg/ml, which was much higher than the MPC against S. pneumoniae (0.5 μg/ml). From these values, we calculated the fCmax/MPC of garenoxacin to be 3.5–4. In addition, the fAUC/MPC was calculated to be 52 h from the population mean AUC of 104 μg·h/ml, suggesting that resistant bacteria are not likely to emerge. The MPC of garenoxacin was five- to tenfold larger than that of the MIC90. Consequently, the 400 mg dose was expected to be effective against common bacteria of respiratory tract infections, as well as to prevent the emergence of resistance.

Tam et al. [34] reported a fAUC/MIC target of 190 h for the suppression of resistance by garenoxacin treatment against P. aeruginosa. As shown in Table 7, this target value was achievable for MSSA, PSSP, PISP, PRSP, H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis and marginal for K. pneumoniae, but not for P. aeruginosa. Thus, the 400 mg dose is not only ineffective but is also insufficient to prevent resistance for P. aeruginosa.

We constructed a final population PK model from studies of phase I trials, a clinical phase II trial of respiratory tract infection (CAP, SICRD), and a clinical phase III study of SICRD. Van Wart et al. [11] also developed a PK model of garenoxacin from phase II studies of North America and Europe for AECB, CAP, and sinusitis. Their PK model included CLCR, ideal body weight, and extent of obesity as covariates of CL/F, and body weight and gender as covariates of V/F. Their covariates other than ideal body weight and obesity extent were the same as our covariates (Table 3). We selected actual body weight instead of ideal body weight and the obesity extent because the Japanese population did not include highly obese subjects. In our population PK analysis, the AUC and Cmax showed an inverse correlation with body weight and renal function (Fig. 2). A standard PK analysis by Krishna et al. [35] reported similar results in that the the AUC in their patients with renal impairment not requiring dialysis (CLCR < 30 ml/min) was 51% higher than that in normal subjects. The necessity of dose adjustment for special populations is suggested by Fig. 2; for example, 200 mg of garenoxacin given to a patient with low body weight (<40 kg) or moderate to severe renal impairment might be enough for adequate efficacy.

We chose SICRD, including AECB, as the investigating target disease for the phase III PK/PD study. Various causative bacteria were observed, including non-susceptible and susceptible bacteria (Table 2). We have identified that the fAUC0−24/MIC ratio was a significant variable associated with the clinical efficacy (Table 6; Fig. 5). On the other hand, a traditional controlled study compares a few doses of the test drug with reference to the standard dose of a comparable drug. The relationship between dose and clinical effect has often been unclear in past studies because of bias in the isolation frequencies of mixed sensitive and insensitive bacteria. In contrast, the PK/PD analysis is able to find an effective dose, stratified by each causative organism. This is an advantage of the PK/PD method, and the results obtained provide stronger scientific rationale. We implemented the PK/PD method for dose selection of garenoxacin (in 2002 after completing the phase II trial) and confirmed the recommended dose by a subsequent phase III trial (conducted during 2002–2005). The comparison of the predicted in silico efficacy against causative bacteria and the results of the clinical trial is a novel learning–confirming method for new drug development. We conducted the model-based drug development throughout the clinical trials of garenoxacin in Japan. This development strategy utilized a combination of the PK/PD concept with the following rationalizations and utility. (1) Certain optimal doses can be predicted early in the drug development process. (2) The selected dose can be confirmed by an appropriate open-label clinical PK/PD study. (3) The altered PK of garenoxacin in a special population, such as patients with renal impairment, can be predicted from a population PK model. (4) Through this adaptive approach the development period can be shortened with a fewer number of trials and patients.

In practice, the PK/PD and Monte Carlo simulation approach led us to use a smaller number of subjects (n = 30 per group), whereas the conventional design usually requires 60 subjects per one group based upon the power calculations for the phase II dose-finding study. An optimal dose could not always be decided upon appropriately by the simple comparison of efficacy rates in different doses. Thus, the risk of failure was relatively high after proceeding to phase III stage. The PK/PD design is advantageous for reducing the time and cost of development by reducing the number of subjects and can increase the success rate of drug development because of the appropriately selected dose.

In conclusion, the optimal dose of garenoxacin for patients with respiratory tract infection has been determined to be 400 mg once daily by the prospective population PK/PD analysis and clinical trial simulations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Diagnostic plots for the final population pharmacokinetic modeling (DOC 352 kb)

Conflict of interest

This was a collaborative work of Keio University with Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd. Yusuke Tanigawara received research funding from Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd. Kenji Nozawa and Hisatsugu Tsuda are employees of Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Fung-Tomc JC, Minassian B, Kolek B, Huczko E, Aleksunes L, Stickle T, Washo T, Gradelski E, Valera L, Bonner DP. Antibacterial spectrum of a novel des-fluoro(6) quinolone, BMS-284756. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3351–3356. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.12.3351-3356.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahata M, Mitsuyama J, Yamashiro Y, Yonezawa M, Araki H, Todo Y, Minami S, Watanabe Y, Narita H. In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activities of T-3811ME, a novel des-F(6)-quinolone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1077–1084. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhanel GG, Palatnick L, Nichol KA, Bellyou T, Low DE, Hoban DJ. Antimicrobial resistance in respiratory tract Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates: results of the Canadian respiratory organism susceptibility study, 1997 to 2002. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1867–1874. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.6.1867-1874.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhanel GG, Palatnick L, Nichol KA, Low DE, The CROSS Study Group. Hoban DJ. Antimicrobial resistance in Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis respiratory tract isolates: results of the Canadian respiratory organism susceptibility study, 1997 to 2002. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1875–1881. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.6.1875-1881.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahata M, Fukuda Y, Futakuchi N, Sugiura Y, Hisada H, Mizunaga S, Oogake N, Ito Y, Shinmura Y, Nakatani M, Tanaka T, Komeno T, Kamiyama T, Mitsuyama J, Todo Y. In vitro antibacterial activity of garenoxacin. Chemotherapy (Tokyo). 2007;55(Suppl. 1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niki Y, Watanabe A, Aoki N, Kohno S. Dose-finding study on telithromycin in bacterial pneumonia. Chemotherapy (Tokyo). 2003;51(Suppl 1):240–254. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito A, Watanabe A, Odagiri S, Aoki N, Matsushima T, Nasu M, Nakashima M, Yamaguchi K, Shimada J. A dose-finding study on doripenem in chronic respiratory tract infection. Chemotherapy (Tokyo). 2005;53(Suppl 1):169–184. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambrose PG, Bhavnani SM, Rubino CM, Louie A, Gumbo T, Forrest A, Drusano GL. Pharmacokinetics–pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial therapy: it's not just for mice anymore. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:79–86. doi: 10.1086/510079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mouton JW. Impact of pharmacodynamics on breakpoint selection for susceptibility testing. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:579–598. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00062-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forrest A, Nix DE, Ballow CH, Goss TF, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ. Pharmacodynamics of intravenous ciprofloxacin in seriously ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1073–1081. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Wart SV, Phillips L, Ludwig EA, Russo R, Gajjar DA, Bello A, Ambrose PG, Costanzo C, Grasela TH, Echols R, Grasela DM. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of garenoxacin in patients with community-acquired respiratory tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4766–4777. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4766-4777.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andes D, Craig WA. Pharmacodynamics of the new des-F(6)-quinolone garenoxacin in a murine thigh infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3935–3941. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3935-3941.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao X, Drlica K. Restricting the selection of antibiotic-resistant mutants: a general strategy derived from fluoroquinolone studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:S147–S156. doi: 10.1086/321841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drlica K. The mutant selection window and antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:11–17. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drusano GL. Antimicrobial pharmacodynamics: critical interactions of 'bug and drug'. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:289–300. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi H, Watanabe A, Aoki N, Odagiri S, Sano Y, Saito A. Clinical phase II study of garenoxacin in patients with respiratory tract infections. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 2007;55(Suppl 1):116–126. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi H, Tanigawara Y, Watanabe A, Aoki N, Sano Y, Odagiri S, Niki Y, Kohno S, Saito A. Phase III study of garenoxacin in patients with secondary infection of chronic respiratory diseases. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 2007;55(Suppl.1):144–161. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uchida E. Phase I clinical studies of oral garenoxacin in healthy Japanese adult subjects. Chemotherapy (Tokyo). 2007;55(Suppl. 1):95–115. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukumoto H, Matsutani H, Yamamoto Y, Sakai H. Determination of garenoxacin and its sulfate conjugate metabolite in human plasma and urine using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Iyakuhin Kenkyu (Tokyo). 2003;34:153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Japan Society of Chemotherapy Method of MIC determination. Chemotherapy (Tokyo). 1981;29:76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2005) Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Document M100-S15. CLSI, Wayne

- 22.Sheiner LB, Beal SL, editors. NONMEM user’s guide. San Francisco: University of California; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduce to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao X, Eisner W, Rosenthal NP, Kreiswirth B, Drlica K. Mutant prevention concentration of garenoxacin (BMS-284756) for ciprofloxacin-susceptible or -resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1023–1027. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.3.1023-1027.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Mariano N, Rahal JJ, Urban CM, Drlica K. Quinolone-resistant Haemophilus influenzae: determination of mutant selection window for ciprofloxacin, garenoxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4460–4462. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4460-4462.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mouton JW, Dudley MN, Cars O, Derendorf H, Drusano GL. Standardization of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) terminology for anti-infective drugs: an update. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:601–607. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyashita N, Matsushima T, Oka M, Society JR. The JRS guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: an update and new recommendations. Intern Med. (Tokyo). 2006;45:419–428. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato R, Tanigawara Y, Kaku M, Aikawa N, Shimizu K. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship of arbekacin for treatment of patients infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:3763–3769. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00480-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanigawara Y, Sato R, Morita K, Kaku M, Aikawa N, Shimizu K. Population pharmacokinetics of arbekacin in patients infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:3754–3762. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00420-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen GP, Kaatz GW, Rybak MJ. Activities of mutant prevention concentration-targeted moxifloxacin and levofloxacin against Streptococcus pneumoniae in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2606–2614. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2606-2614.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blondeau J, Borsos S, Hedlin P, Hansen G (2003) Determination of the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and mutation prevention concentration (MPC) for garenoxacin against clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. In: Raoult D (ed) Poster No. P1540 presented at 13th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2003. Clin Microbiol Infect 9(1):375. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp 1–422

- 33.Homma T, Hori T, Sugimori G, Yamano Y. Pharmacodynamic assessment based on mutant prevention concentrations of fluoroquinolones to prevent the emergence of resistant mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3810–3815. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01372-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tam VH, Louie A, Deziel MR, Liu W, Leary R, Drusano GL. Bacterial-population responses to drug-selective pressure: examination of garenoxacin’s effect on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:420–428. doi: 10.1086/430611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishna G, Gajjar D, Swan S, Marbury T, Grasela DM, Wang Z. Garenoxacin pharmacokinetics in subjects with renal impairment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:649–657. doi: 10.1185/030079906X167679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Diagnostic plots for the final population pharmacokinetic modeling (DOC 352 kb)