Abstract

Summary

Dosing regimens of oral bisphosphonates are inconvenient and contribute to poor compliance. The bone mineral density response to a once weekly delayed-release formulation of risedronate given before or following breakfast was non-inferior to traditional immediate-release risedronate given daily before breakfast. Delayed-release risedronate is a convenient regimen for oral bisphosphonate therapy.

Introduction

We report the results of a randomized, controlled, clinical study assessing the efficacy and safety of a delayed-release (DR) 35 mg weekly oral formulation of risedronate that allows patients to take their weekly risedronate dose before or immediately after breakfast.

Methods

Women with postmenopausal osteoporosis were randomly assigned to receive risedronate 5 mg immediate-release (IR) daily (n = 307) at least 30 min before breakfast, or risedronate 35 mg DR weekly, either at least 30 min before breakfast (BB, n = 308) or immediately following breakfast (FB, n = 307). Bone mineral density (BMD), bone turnover markers (BTMs), fractures, and adverse events were evaluated. The primary efficacy variable was percent change from baseline in lumbar spine BMD at Endpoint.

Results

Two hundred fifty-seven subjects (83.7%) in the IR daily group, 252 subjects (82.1%) in the DR FB weekly group, and 258 subjects (83.8%) in the DR BB weekly group completed 1 year. Both DR weekly groups were determined to be non-inferior to the IR daily regimen. Mean percent changes in hip BMD were similar across groups. The magnitude of BTM response was similar across groups; some statistical differences were seen that were small and deemed by investigators to have no major clinical importance. The incidence of adverse events leading to withdrawal and serious adverse events were similar across treatment groups. All three regimens were well tolerated.

Conclusions

Risedronate 35 mg DR weekly is similar in efficacy and safety to risedronate 5 mg IR daily, and will allow patients to take their weekly risedronate dose immediately after breakfast.

Keywords: Bone mineral density, Delayed-release, Enteric-coated, Fracture risk, Osteoporosis, Risedronate, Weekly

Introduction

Bisphosphonates are the standard of care for the treatment of osteoporosis. Oral bisphosphonates are available in various formulations with different dosing frequencies (i.e., daily, weekly, and monthly) for patient convenience. However, all oral bisphosphonates require patients to follow strict dosing instructions to derive full benefit from the drug. Dosing instructions outlined in product labels for oral bisphosphonates require that they be taken on an empty stomach at least 30 to 60 min before the first food, drink, or other medication of the day [1–3]. Many patients perceive this requirement to be inconvenient, and in one study, 33.5% stated they did not wait for the minimum 30 min to eat after taking their bisphosphonate [4].

The 30–60 min “before food or drink” requirement is necessary for oral bisphosphonates due to decreased absorption in the presence of food. Food and drink (other than water) contain calcium and other polyvalent cations that form complexes with bisphosphonates, rendering them unavailable for absorption [5]. In pivotal studies in which the efficacy of oral bisphosphonates was established, 30–60 min “before food or drink” dosing intervals were used to ensure the amount of drug absorbed was adequate to produce a clinically relevant efficacy response. The importance of the “before food or drink” restriction is supported by pharmacokinetic studies which have reported bioavailability to be negligible [1] to 87–90% lower in the fed state [6, 7] compared to when the “before food or drink” period is strictly followed. The clinical impact of this food effect was demonstrated by Agrawal and colleagues who showed that dosing risedronate between meals did not alter bone turnover in nursing home residents [8]. Additionally, Kendler and colleagues demonstrated that the lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) response to risedronate 5 mg daily given between meals and at least 2 h from a meal was smaller (1.5% at 6 months) than when the same dose was administered at least 30 min before breakfast (2.9%) [9]. Given the magnitude of reduction in absorption with food and the high percentage of patients who admit not complying with label instructions regarding “before food or drink”, reduction in the benefits of bisphosphonate therapy becomes a relevant clinical concern.

This study describes an innovative delayed-release (DR) formulation of risedronate that ensures adequate bioavailability of risedronate when taken with food. The 35 mg once-a-week enteric-coated tablet delivers risedronate to sites beyond the stomach where concentrations of substances that interfere with its absorption are lower. In addition, a chelating agent included in the formulation competitively binds cations such as calcium that may be present in the area of absorption. This new DR formulation eliminates the restriction to take risedronate prior to the first food or drink in the morning and ensures adequate bioavailability and pharmacological availability of risedronate.

To test the safety and efficacy of risedronate 35 mg DR weekly in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, a randomized, double-blind, study was undertaken comparing the 35 mg weekly DR tablet to the 5 mg daily immediate-release (IR) tablet. This phase III study was designed to test the non-inferiority (based on the percent change in lumbar spine BMD from baseline after 1 year) of the risedronate 35 mg DR weekly formulation taken before or after breakfast compared to the 5 mg daily IR dose taken per label. Comparison to the 5 mg daily dose of risedronate IR instead of the 35 mg weekly dose was performed to meet regulatory guidelines for the approval of new formulations of a previously approved drug. The efficacy and safety results for the first year of the study are reported here.

Methods and materials

Study design

This randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, parallel-group study was conducted at 43 study centers in North America, South America, and the European Union. The first subject was screened in November 2007, and the last subject observation for the first year of the study took place in April 2009. The study was performed in accordance with good clinical practice and the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the appropriate institutional review boards or ethics committees, and the subjects gave written, informed consent to participate.

Subjects

Women were eligible to enroll in the study if they were at least 50 years of age, ambulatory, in generally good health, postmenopausal (at least 5 years since last menses), had at least three vertebral bodies in the lumbar spine (L1 to L4) evaluable by densitometry (i.e., without fracture or degenerative disease), and had a lumbar spine or total hip BMD corresponding to a T-score of −2.5 or lower or a T-score of −2.0 or lower with at least one prevalent vertebral fracture (T4 to L4). Exclusion criteria included contraindications to oral bisphosphonate therapy, lumbar spine BMD corresponding to a T-score of −5 or lower, use of medications that could interfere with the study evaluations, conditions that would interfere with the BMD measurements, bilateral hip prostheses, body mass index greater than 32 kg/m2, allergy to bisphosphonates, history of cancer in the last 5 years (excluding basal or squamous skin cancers or successfully treated cervical cancer in situ), drug or alcohol abuse, abnormal clinical laboratory measurements, creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min, hypo- or hypercalcemia, history of hyperparathyroidism or hyperthyroidism (unless corrected), osteomalacia, and any previous or ongoing condition that the investigator judged could prevent the subject from being able to complete the study. Eligible subjects who gave consent were stratified by anti-coagulant use (since fecal occult blood testing was performed during the study) and randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to the three treatment groups.

Treatments

Subjects received oral risedronate 5 mg IR daily at least 30 min before breakfast or risedronate 35 mg DR once a week, taken either at least 30 min before or immediately following breakfast. All subjects took nine study tablets each week: an IR study tablet daily plus a DR study tablet before breakfast and another following breakfast on a single specified day of the week. All placebo tablets were identical in appearance to their corresponding 5 mg IR and 35 mg DR active tablets and supplied in identical blister cards. All tablets were taken with at least 4 oz of plain water, and subjects were instructed to remain in an upright position for at least 30 min after dosing. Compliance was assessed by tablet counts; subjects were determined to be compliant if they took at least 80% of the study tablets. Calcium (1,000 mg/day) and vitamin D (800–1000 IU/day) were supplied to all subjects who were instructed to take these supplements with a meal other than breakfast and not with the study medication.

Efficacy assessments

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measurements of lumbar spine and proximal femur were obtained at baseline and after 26 and 52 weeks using instruments manufactured by Lunar Corporation (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA) or Hologic (Waltham, MA, USA). DXA scans collected at the clinical sites were sent to a central facility for quality control and analysis (Synarc, San Francisco, CA, USA).

New incident vertebral fractures were assessed by semi-quantitative morphometric analysis [10] of lateral thoracic and lumbar spine radiographs collected at screening and after 52 weeks. Radiographs were reviewed for quality and analyzed for fracture at a central site (Synarc, San Francisco, CA, USA).

Biochemical markers of bone turnover were assessed in fasting samples at baseline and after 13, 26, and 52 weeks. Serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BAP) was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (MicroVue BAP, Metra Biosystems, Santa Clara, CA, USA) on an automatic plate reader (VersaMax ELISA Plate Reader, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation for this measurement were less than 4% and 8%, respectively. The detection limit of the test was 0.7 IU/l and the limit of quantitation was 140 IU/l. Urinary type-1 collagen cross-linked N-telopeptide (NTX) was measured with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Osteomark, Inverness Medical Professional Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ, USA) on an automated plate reader (VersaMax ELISA Plate Reader, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were below 7% and 9%, respectively. The detection limit of the test was 20 nM and the limit of quantitation was 3000 nM. This measurement was corrected for creatinine (NTX/creatinine). For this correction, urinary creatinine was measured using a rate-blanked modified Jaffe reaction. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 2.4% and 3.4%, respectively, and the linear range was 3.6 to 650.0 mg/dl. Serum type-1 collagen cross-linked C-telopeptide (CTX) was measured using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Serum CrossLaps®, Immunodiagnostic Systems, Boldon, UK) on an automated plate reader (Victor III ELISA Plate Reader, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were below 15% and 10%, respectively. The lower limit of detection was 0.01 ng/ml. The bone turnover marker assays were performed at a central laboratory (Pacific Biometrics, Seattle, WA, USA).

Safety assessments

Physical examinations were performed at baseline and after 52 weeks. Vital signs, concomitant medications, and adverse event reports were recorded at regular clinic visits throughout the study. Blood and urine samples for standard laboratory measurements were collected at baseline and after 13, 26, and 52 weeks of treatment. Serum chemistry measurements were obtained after 14 days. Specimens were analyzed by Quintiles Central Laboratory (Marietta, GA, USA). Fecal occult blood samples were collected at baseline and after 26 weeks, and 12-lead electrocardiograms were assessed at baseline and after 52 weeks.

Statistical analysis

The primary Endpoint analysis was a non-inferiority test comparing the least squares mean percent change from baseline in lumbar spine BMD in the DR weekly and the IR daily groups after 52 weeks. The analysis followed a fixed-sequence test procedure, with the first comparison being the DR FB weekly group and the IR daily group. If, and only if, the DR FB weekly group was declared non-inferior to the IR daily group, the second comparison of the DR BB weekly group versus the 5 mg IR daily group was performed. The test employed a pre-defined non-inferiority margin of 1.5% (chosen based on data from previous risedronate studies) and a 1-sided type I error of 2.5%. The primary efficacy variable is the percent change from baseline in lumbar spine BMD at Endpoint; the last valid post-baseline measurement was used when the Week 52 value was missing (LOCF). The primary analysis population was all subjects who were randomized, received at least one dose of study drug, and had analyzable lumbar spine BMD data at baseline and at least one post-treatment time point. Investigative centers were pooled by geographic region prior to unblinding. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with treatment, anti-coagulation medication use, and pooled centers as fixed effects, baseline lumbar spine BMD as a covariate, and percent change from baseline in lumbar spine BMD at Endpoint as the response variable. As a secondary efficacy analysis, if the DR weekly groups were both non-inferior to the IR daily group, the DR weekly groups were pooled and a test of their superiority to the IR daily group was performed using ANOVA methods similar to those used for the primary analysis. Other continuous secondary efficacy variables were also analyzed using ANOVA methods similar to those used for the primary analysis. Ninety-five percent, two-sided confidence intervals (CIs) for the treatment difference were constructed and used to determine differences between IR daily and each of the DR weekly treatment groups. To assess the homogeneity of the treatment effects across pooled centers, the percent change from baseline in lumbar spine BMD at Endpoint was analyzed using an ANOVA model with terms for treatment, baseline lumbar spine BMD, anti-coagulant use, pooled center, and treatment-by-pooled center interaction. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed using two separate models to assess the effects of calcium and vitamin D supplement levels and the corresponding interactions; average daily dose was applied as the supplement level. The proportion of patients with at least one new vertebral body fracture of the thoracic or lumbar spine was compared to the IR daily group using the Fisher’s exact test for each DR group separately. The proportion of patients with adverse events by category was compared across all treatment groups using an overall Fisher’s exact test. Baseline characteristics of the treatment groups were compared using one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Unless noted otherwise, all statistical analyses were two-sided, with a type I error rate of 0.05, and no adjustments were made for multiplicity.

Results

Subjects

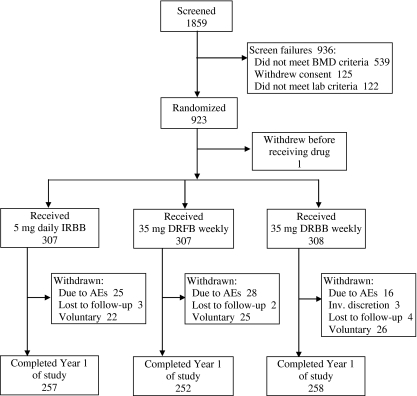

From 1,859 women who were screened, 923 subjects were randomized, and 922 subjects received at least one dose of study drug (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics were similar across treatment groups (Table 1). A similar percentage of subjects in each treatment group completed 12 months of the study (IR daily group, 83.7%; DR FB weekly group, 82.1%; DR BB weekly group, 83.8%). The most common reasons given for withdrawal were adverse event and voluntary withdrawal, which occurred at similar incidences across all three treatment groups. Voluntary withdrawals were, by definition, unrelated to adverse events and usually were attributed by the subject to inconvenience or inability to travel to the clinic. A high percentage of intent-to-treat subjects in all groups (94.8% of subjects in the IR daily group, 96.1% of subjects in the DR FB weekly group, and 91.9% of subjects in the DR BB weekly group) took at least 80% of the study tablets.

Fig. 1.

Disposition of subjects

Table 1.

Summary of baseline characteristics

| Risedronate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg IR daily | 35 mg DR FB weekly | 35 mg DR BB weekly | |

| (N = 307) | (N = 307) | (N = 308) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 65.3 (7.4) | 65.8 (7.4) | 66.0 (7.5) |

| Years since menopause, mean (SD) | 17.5 (8.6) | 18.2 (8.0) | 18.8 (8.5) |

| Years since last menses (n [%]) | |||

| 5 to 10 years | 78 (25.4) | 60 (19.5) | 62 (20.1) |

| More than 10 years | 229 (74.6) | 247 (80.5) | 246 (79.9) |

| Race (n [%]) | |||

| White | 306 (99.7) | 305 (99.3) | 306 (99.4) |

| Asian (Oriental) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multi-racial | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) |

| Prevalent vertebral fracture (n [%]) | 70 (24.1)a | 81 (28.2)a | 87 (29.1)a |

| Standardizedb lumbar spine bone BMD (mg/cm2), mean (SD) | 762 (60) | 763 (68) | 763 (73) |

| Lumbar spine BMD T-score, mean (SD) | −3.12 (0.52) | −3.11 (0.59) | −3.11 (0.56) |

| Standardizedb total proximal femur BMD (mg/cm2), mean (SD) | 591 (178) | 593 (162) | 593 (171) |

| Proximal femur BMD T-score, mean (SD) | −2.96 (1.44) | −2.95 (1.32) | −2.94 (1.39) |

| Urinary NTX/creatinine (nmol BCE/mmol creatinine), mean (SD) | 76.1 (33.0) | 74.8 (36.1) | 72.7 (33.7) |

| Serum CTX (ng/mL). mean (SD) | 0.643 (0.272) | 0.642 (0.288) | 0.671 (0.849) |

| Serum BAP (μg/L), mean (SD) | 28.6 (9.6) | 27.3 (8.4) | 27.5 (8.4) |

BAP bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, BB before breakfast, BMD bone mineral density, CTX type-1 collagen cross-linked C-telopeptide, DR delayed-release, FB following breakfast, IR immediate-release, NTX type-1 collagen cross-linked N-telopeptide corrected for creatinine

aPercent is based upon the number of subjects with known vertebral fracture status (5 mg IR daily group, 291; 35 mg DRFB weekly group, 287; 35 mg DRBB weekly group, 299)

bAdjusted to account for machine type [10]

Efficacy assessments

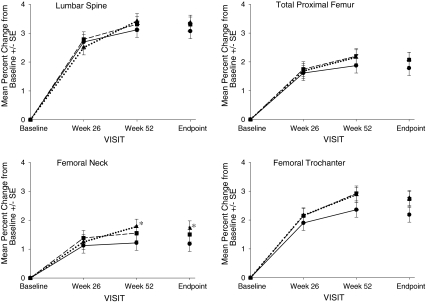

The least squares mean percent change (95% CI) from baseline in lumbar spine BMD at Endpoint was 3.3% (2.89% to 3.72%) in the DR FB weekly group and 3.1% (2.66% to 3.47%) in the IR daily group, indicating both groups experienced significant improvement from baseline in lumbar spine BMD (Fig. 2). The difference between the IR daily group and the DR FB group was −0.233%, with a 95% CI of −0.812% to 0.345%. The upper limit of the CI for the difference between the groups was less than the pre-defined non-inferiority margin of 1.5%. Therefore, the 35 mg DR tablet, when taken once a week after breakfast, was determined to be non-inferior to the 5 mg IR daily regimen with respect to percent changes in lumbar spine BMD. The least squares mean percent change (95% CI) from baseline in lumbar spine BMD at Endpoint for the DR BB weekly group was 3.4% (2.96% to 3.77%), indicating the DR BB group experienced significant improvement from baseline in lumbar spine BMD. The difference between the IR daily group and the DR BB weekly group was −0.296%, with a 95% CI of −0.869% to 0.277%. As for the DR FB weekly group, the upper limit of the CI for the difference between the IR daily group and the DR BB group was less than the pre-defined non-inferiority margin of 1.5%; therefore, the 35 mg DR tablet, when taken once a week at least 30 min before breakfast, was also deemed to be non-inferior to the 5 mg IR daily regimen with respect to percent changes in lumbar spine BMD. The treatment-by-pooled center interaction was not significant, indicating the treatment effect was consistent across geographies. When the DR weekly groups are combined, the 35 mg DR weekly regimen was determined not to be superior to the 5 mg IR daily regimen. There were no statistically significant differences between either of the DR weekly groups and the IR daily group in mean percent change from baseline in lumbar spine BMD at any time point (i.e., Week 26, Week 52, or Endpoint). There were no significant interactions between treatment and the average daily dose of either calcium or vitamin D supplements (p > 0.1), indicating that the treatment effect was consistent across calcium or vitamin D supplement levels.

Fig. 2.

Mean percent change from baseline ± SE in BMD over 1 year in women receiving risedronate 5 mg IR daily  , 35 mg DRFB weekly

, 35 mg DRFB weekly  , or 35 mg DRBB weekly

, or 35 mg DRBB weekly  . The Endpoint value is calculated using LOCF at Week 52. Asterisk statistically significant difference between IR daily and each of the DR weekly treatment groups

. The Endpoint value is calculated using LOCF at Week 52. Asterisk statistically significant difference between IR daily and each of the DR weekly treatment groups

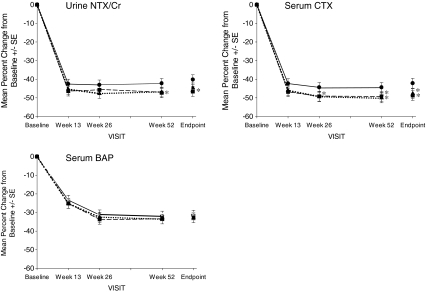

Significant increases from baseline in BMD at sites in the hip (total proximal femur, femoral neck, femoral trochanter) were observed at 26 and 52 weeks and Endpoint in all treatment groups (Fig. 2). As was the case for lumbar spine BMD, there were no statistically significant differences between either of the DR weekly regimens and the IR daily regimen at any time point for the total proximal femur and the femoral trochanter. At the femoral neck, no statistically significant differences were seen between the DR FB weekly and the IR daily groups at any time point; however, statistically greater increases in BMD at Week 52 and Endpoint were seen in the DR BB weekly group compared to the IR daily group (least squares mean difference in percent change from baseline at Endpoint = −0.537; 95% CI −1.000, −0.074). Significant decreases from baseline in NTX/creatinine, CTX, and BAP were observed at 13, 26, and 52 weeks in all treatment groups (Fig. 3). Small differences were observed in the responses of resorption markers between the DR weekly groups and the IR daily group. Compared to the IR daily regimen, the decrease in urinary NTX/creatinine was statistically greater with DR FB weekly dosing at Week 52 and Endpoint, and the reduction in serum CTX was significantly greater in the DR FB weekly group at Weeks 26 and 52 and at Endpoint and with the DR BB dose at Endpoint.

Fig. 3.

Mean percent change from baseline ± SE in bone turnover markers over 1 year in women receiving risedronate 5 mg IR daily  , 35 mg DRFB weekly

, 35 mg DRFB weekly  , or 35 mg DRBB weekly

, or 35 mg DRBB weekly . The Endpoint value is calculated using LOCF at Week 52. Asterisk statistically significant difference between IR daily and each of the DR weekly treatment groups

. The Endpoint value is calculated using LOCF at Week 52. Asterisk statistically significant difference between IR daily and each of the DR weekly treatment groups

New incident morphometric vertebral fractures during the first 52 weeks of treatment occurred in two subjects in the IR daily group, 2 subjects in the DR FB weekly group, and 3 subjects in the DR BB weekly group. There were no statistically significant differences between either of the DR weekly groups and the IR daily group.

Safety assessments

Overall, the adverse event profile was similar across the three treatment groups during the first 52 weeks of treatment (Table 2). The incidence of upper gastrointestinal adverse events was numerically but not significantly higher in the DR BB weekly group than in the IR daily or DR FB weekly groups, mostly due to a significantly higher incidence of upper abdominal in the DR BB group (p value = 0.0041). These events were all judged to be mild or moderate. The incidence of lower gastrointestinal adverse events was slightly but not significantly higher in the DR FB weekly group than in the IR daily or DR BB weekly groups, mostly due to events of mild to moderate diarrhea. The frequency of gastrointestinal adverse events with daily IR risedronate and the DR doses in this study is consistent with previous studies of daily, weekly, and monthly dosing with risedronate [11–13].

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events

| Risedronate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg IR daily | 35 mg DR FB weekly | 35 mg DR BB weekly | |

| (N = 307) | (N = 307) | (N = 308) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Adverse events | 211 (68.7) | 222 (72.3) | 238 (77.3) |

| Serious adverse events | 22 (7.2) | 20 (6.5) | 21 (6.8) |

| Deaths | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Withdrawn due to an adverse event | 25 (8.1) | 28 (9.1) | 19 (6.2) |

| Most common adverse events associated with withdrawal | |||

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 11 (3.6) | 17 (5.5) | 13 (4.2) |

| Most common adverse events | |||

| Influenza | 19 (6.2) | 22 (7.2) | 18 (5.8) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 16 (5.2) | 21 (6.8) | 26 (8.4) |

| Arthralgia | 24 (7.8) | 21 (6.8) | 19 (6.2) |

| Back pain | 18 (5.9) | 21 (6.8) | 19 (6.2) |

| Adverse events of special interest | |||

| Clinical vertebral fracture | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) |

| Clinical nonvertebral fracture | 5 (1.6) | 9 (2.9) | 10 (3.2) |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract adverse events | 45 (14.7) | 48 (15.6) | 61 (19.8) |

| Diarrhea | 15 (4.9) | 27 (8.8) | 18 (5.8) |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (2.9) | 16 (5.2) | 15 (4.9) |

| Upper abdominal paina | 7 (2.3) | 9 (2.9) | 23 (7.5) |

| Constipation | 9 (2.9) | 15 (4.9) | 16 (5.2) |

| Selected musculoskeletal adverse eventsb | 46 (15.0) | 48 (15.6) | 53 (17.2) |

| Adverse events potentially associated with acute phase reactionc | 4 (1.3) | 7 (2.3) | 4 (1.3) |

a p value = 0.0041

bIncludes arthralgia, back pain, bone pain, musculoskeletal pain, musculoskeletal discomfort, myalgia, and neck pain

cIncludes symptoms of influenza-like illness or pyrexia with a start date within the first 3 days after the first dose of study drug and duration of 7 days or less

Other adverse events of special interest for bisphosphonates include clinical fractures, musculoskeletal adverse events, and acute phase reaction adverse events. Clinical fractures are defined as all nonvertebral fractures and symptomatic, radiographically confirmed vertebral fractures that occurred after randomization and were reported as adverse events. Acute phase reactions are defined as influenza-like illness and/or pyrexia starting within 3 days following the first dose of study drug and having a duration of 7 days or less. Clinical vertebral and nonvertebral fractures occurred infrequently. The numeric differences noted were not statistically significant, and the types of fractures were similar among the treatment groups. Musculoskeletal adverse events were reported by similar proportions of subjects across treatment groups (Table 2). No cases of acute phase reaction or osteonecrosis of the jaw were reported.

Small decreases in serum calcium and the expected reciprocal increases in serum iPTH 1–84 were seen within the first few weeks of treatment, as expected upon initiation of antiresorptive therapy. These changes were transient and were not symptomatic or clinically meaningful. No clinically important differences were seen across groups for any laboratory parameter measured, including measures of hepatic and renal function.

Other laboratory safety parameters, including fecal occult blood tests, coagulation parameters, and electrocardiograms, revealed no adverse safety signals.

Discussion

Risedronate, as an IR tablet, has proven vertebral and nonvertebral antifracture efficacy. Due to poor bioavailability in the presence of food with all bisphosphonates, it is important that these medications be taken before the first food or drink of the day for optimal efficacy. With risedronate, patients must wait at least 30 min after dosing before eating or drinking anything other than water. This study has shown that the novel risedronate 35 mg DR tablet, when taken once weekly either before or after breakfast, produces clinical effects similar to those seen with the risedronate 5 mg IR tablet taken daily as prescribed. Specifically, the mean percent changes in lumbar spine BMD at 52 weeks in the DR weekly groups were non-inferior to the mean percent change in the IR daily group. Changes in secondary efficacy parameters, including BMD at the hip, bone turnover markers and new morphometric vertebral fractures were generally similar in both DR weekly groups compared to the IR daily group. Statistically significant increases in femoral neck BMD, and decreases in bone turnover markers, were seen at some time points in the DR weekly groups compared to the IR daily group. The reason for the somewhat increased responses to the DR regimen is unclear but is probably not explained by the difference in daily versus weekly dosing since the BMD and marker responses to daily and weekly risedronate IR did not differ [14]. Even a modestly better bioavailability of the DR formulation compared to IR during the year of therapy could account for the difference. Alternatively, perhaps compliance with dosing instructions was better with the weekly DR regimen compared to the daily IR regimen, even in the context of clinical trial where compliance with therapy is generally better than in daily clinical practice.

The risedronate DR weekly regimen was generally well tolerated by postmenopausal women, with a safety profile similar to that seen with the risedronate daily regimen. Although upper abdominal pain and diarrhea were more frequent in the DR weekly groups, few subjects withdrew due to the events. Most events were mild or moderate in severity, suggesting these symptoms with the 35 mg DR weekly regimen will have a minimal impact on adherence to treatment in clinical use.

The vertebral and nonvertebral antifracture efficacy of risedronate has been established in multiple large studies that had fracture as the primary Endpoint [12, 15, 16]. BMD change is an appropriate surrogate Endpoint when evaluating a new dosing regimen for a bisphosphonate for which a fracture benefit has already been established. Similar non-inferiority trials have been conducted previously to evaluate new dosing regimens of oral and intravenous bisphosphonates [11, 17, 18], and this approach has been accepted by both the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency [14] for approval of new regimens of established agents. The Year 1 BMD results observed in this study are consistent with what has been observed in the pivotal antifracture studies and other previous studies of risedronate IR weekly and monthly dosing regimens [11, 13, 19].

These results were obtained with specific dosing regimens. The data presented here pertain only to dosing with risedronate DR at least 30 min before or immediately after breakfast and may not reflect the responses to taking the new formulation at other times. It is also important to note that calcium supplements were taken at a time of day different than the risedronate doses and that the effect of taking calcium supplements around the time of breakfast on the day the DR formulation was taken is not known. All subjects were required to remain upright after taking the study tablets since they might have been taking risedronate IR. As a result, the requirement to remain upright after dosing persists with risedronate DR. In theory, having the DR formulation disintegrate in the small intestine rather than the esophagus or stomach should decrease the potential for reflux of the drug into the esophagus and esophageal irritation. The study was not designed to evaluate that outcome.

In summary, the risedronate 35 mg DR weekly dosing regimen, taken before or following breakfast, was similar in efficacy and tolerability to risedronate 5 mg IR daily dosing in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. By minimizing the impact of concomitantly ingested food on the bioavailability of risedronate, the 35 mg DR tablet, taken in the morning once a week without regard to food or drink, could make it easier for patients to accept and comply with therapy, thus improving the effectiveness of risedronate in clinical practice. Risedronate 35 mg as a delayed-release tablet taken once weekly before or after breakfast provides a simplified dosing regimen for the patient while ensuring the full efficacy of risedronate.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Chandrasekhar Kasibhatla (Warner Chilcott Pharmaceuticals Inc.) for his technical assistance, and Gayle M. Nelson (Warner Chilcott Pharmaceuticals Inc.) and Barbara McCarty Garcia for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors are responsible for the content, editorial decisions, and opinions expressed in the article.

The authors would also like to thank the other principal investigators who participated in this study. The principal investigators at each study site were: Argentina—C. Magaril, Buenos Aires; Z. Man, Buenos Aires; C. Mautalen, Buenos Aires; J. Zanchetta, Buenos Aires. Belgium—J.-M. Kaufman, Gent. Canada—W. Bensen, Hamilton, Ontario; J. Brown, Québec; R. Faraawi, Kitchener, Ontario; W. Olszynski, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; L.-G. Ste.-Marie, Québec. Estonia—K. Maasalu, Tartu; K.-L. Vahula, Pärnu; I. Valter, Tallinn. France—C. L. Benhamou, Orleans; R. Chapurlat, Lyon; P. Fardellone, Amiens; G. Werhya, Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy. Hungary—Á. Balogh, Debrecen; K. Horváth, Győr; P. Lakatos, Budapest; L. Korányi, Balatonfüred; K. Nagy, Eger. Poland—J. Badurski, Bialystok; J. K. Łącki, Warszawa; E. Marcinowska-Suchowierska, Warszawa; A. Racewicz, Białystok. United States—M. Bolognese, Bethesda, MD; D. Brandon, San Diego, CA; R. Feldman, South Miami, FL; W. Koltun, San Diego, CA; R. Kroll, Seattle, WA; M. McClung, Portland, OR; P. Miller, Lakewood, CO; J. Mirkil, Las Vegas, NV; A. Moffett, Jr., Leesburg, FL; S. Nattrass, Seattle, WA; C. Recknor, Gainesville, GA; K. Saag, Birmingham, AL; J. Salazar, Melbourne, FL; R.A. Samaan, Brockton, MA; S. Trupin, Champaign, IL; M. Warren, Greenville, NC; R. Weinstein, Walnut Creek, CA.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. McClung has received grants and/or is a consultant for Amgen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott.

Dr. Miller is consultant and/or a member of the Speakers or Advisory Boards of Amgen, Eli Lilly, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott.

Dr. Brown is a consultant to Abbott, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott, a board member of Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott, and a member of the Speakers’ Bureaus for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott.

Dr. Zanchetta has received grants from Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, and Warner Chilcott Pharmaceuticals. He is a consultant and/or member of Advisory Boards for Amgen, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Servier.

Dr. Bolognese is a lecturer and/or member of the Speakers’ Bureaus for Amgen, Lilly, and Genentech.

Dr. Benhamou is a board member of Amgen, Novartis, and Merck, a member of the Speakers’ Boards for Amgen, Servier, Novartis, and Roche, and has received grants from Amgen and Servier.

Dr. Balske was previously employed by and holds stock in the Procter & Gamble Company.

Mr. Burgio is employed by and holds stock in the Procter & Gamble Company.

Mr. Sarley was previously employed by Warner Chilcott Pharmaceuticals and the Procter & Gamble Company and holds stock in the Procter & Gamble Company.

Ms. McCullough was previously employed by Warner Chilcott Pharmaceuticals and the Procter & Gamble Company and holds stock in the Procter & Gamble Company.

Dr. Recker is a consultant for Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, NPS Allelix, Procter & Gamble, Roche, and Wyeth, and has received grants/research support from Amgen, Glaxo Smith Kline, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, NPS Allelix, Procter & Gamble, Roche, sanofi aventis, and Wyeth.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00541658

This study was funded and supported by Warner Chilcott Pharmaceuticals Inc. (formerly Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) and sanofi aventis, Inc. for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and editorial assistance for the manuscript.

References

- 1.Merck & Co., Inc. Fosamax® Prescribing Information. http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/f/fosamax/fosamax_pi.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2011

- 2.Warner Chilcott. Actonel® Prescribing Information. http://actonel.com/global/prescribing_information.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2011

- 3.Roche Therapeutics, Inc. Boniva® Prescribing Information. http://www.rocheusa.com/products/Boniva/PI.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2011

- 4.Ettinger B, Pressman A, Schein J, Chan J, Silver P, Connolly N. Alendronate use among 812 women: prevalence of gastrointestinal complaints, noncompliance with patient instructions, and discontinuation. J Manag Care Pharm. 1998;4(5):488–492. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleisch H (2000) Pharmacokinetics. In: Bisphosphonates in bone disease: from the laboratory to the patient. 4th ed. San Diego: Academic. p. 56–62

- 6.Barrett J, Worth E, Bauss F, Epstein S. Ibandronate: a clinical pharmacological and pharmacokinetic update. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:951–965. doi: 10.1177/0091270004267594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogura Y, Gohsho A, Cyong J-C, Orimo H. Clinical trial of risedronate in Japanese volunteers: a study on the effects of timing of dosing on absorption. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22(2):120–126. doi: 10.1007/s00774-003-0459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal S, Krueger DC, Engelke JA, et al. Between-meal risedronate does not alter bone turnover in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):790–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kendler DL, Ringe JD, Ste-Marie LG, et al. Risedronate dosing before breakfast compared with dosing later in the day in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20(11):1895–1902. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0893-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genant HK, Wu CY, Van Kuik C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(9):1137–1148. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JP, Kendler DL, McClung MR, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of risedronate once a week for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;71(2):103–111. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-2011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reginster JY, Minne HW, Sorensen O, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(1):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s001980050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delmas PD, McClung MR, Zanchetta JR, et al. Efficacy and safety of risedronate 150 mg once a month in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;42(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Guideline on the evaluation of medicinal products in the treatment of primary osteoporosis. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003405.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2011

- 15.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA. 1999;282(14):1344–1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(5):333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller PD, McClung MR, Macovei L, et al. Monthly oral ibandronate therapy in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 1-year results from the MOBILE study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(8):1315–1322. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delmas PD, Silvano A, Strugala C, et al. Intravenous ibandronate injections in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: one year results from the dosing intravenous administration study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(6):1838–1846. doi: 10.1002/art.21918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClung MR, Benhamou C-L, Man Z, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of a monthly dosing regimen of 75 mg risedronate dosed on 2 consecutive days a month for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-1 year study results [abstract] Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(Suppl 2):S217–S218. [Google Scholar]