Abstract

Background

The optimal timing of surgery for infective endocarditis complicated by embolic stroke is unclear. We compared early versus delayed surgery in these patients.

Materials and Methods

Between 1992 and 2007, 56 consecutive patients underwent open cardiac surgery for the treatment of infective endocarditis complicated by acute septic embolic stroke, 34 within 2 weeks (early group) and 22 more than 2 weeks (delayed group) after the onset of stroke.

Results

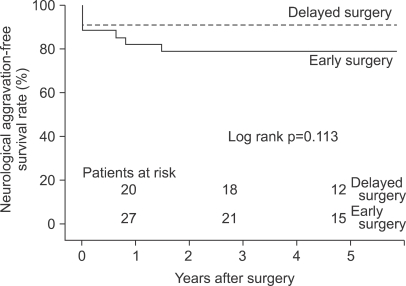

The mean age at time of surgery was 45.7±14.8 years. Stroke was ischemic in 42 patients and hemorrhagic in 14. Patients in the early group were more likely to have highly mobile, large (>1 cm in diameter) vegetation and less likely to have hemorrhagic infarction than those in the delayed group. There were two (3.7%) intraoperative deaths, both in the early group and attributed to neurologic aggravation. Among the 54 survivors, 4 (7.1%), that is, 2 in each group, showed neurologic aggravation. During a median follow-up of 61.7 months (range, 0.4~170.4 months), there were 5 late deaths. Overall 5-year neurologic aggravation-free survival rates were 79.1±7.0% in the early group and 90.9±6.1% in the delayed group (p=0.113).

Conclusion

Outcomes of early operation for infective endocarditis in stroke patients were similar to those of the conventional approach. Early surgical intervention may be preferable for patients at high risk of life-threatening septic embolism.

Keywords: Endocarditis, Embolism, Stroke, Neurologic manifestations, Cerebral complicaton

INTRODUCTION

Although optimal medical management consists of antimicrobial medications, about 20% to 40% of patients with infective endocarditis (IE) experience neurologic complications [1-4]. The most common of these complications, septic embolic stroke due to endocardial vegetation, is associated with a high mortality rate and poor prognosis [5]. Although early surgery in patients with IE plus septic embolic stroke may reduce the risk of further embolic episodes by eliminating its sources, cardiopulmonary bypass during the acute phase of neurologic events may exacerbate neurologic symptoms in these patients. It has been recommended that cardiac surgery for these patients be deferred until after 2 to 4 weeks of optimal medical treatment [6,7]. However, the proper timing of cardiac surgery in this setting remains unclear. We therefore evaluated patient outcomes relative to the timing of surgery for IE in patients with acute embolic stroke. We compared the composite endpoint of death and neurologic aggravation in patients who underwent early surgery (within 2 weeks of stroke onset) and delayed surgery (after 2 weeks).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From January 1992 to December 2007, 317 consecutive patients underwent open cardiac surgery for the treatment of IE in our institution. The diagnosis of IE was based on the modified Duke criteria [8]. Of these, 56 patients had IE complicated by acute septic embolic stroke at the time of presentation. Signs of acute embolic stroke included cerebral infarction and cerebral hemorrhage. Patients were evaluated neurologically or by brain imaging, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 51 patients (91.1%) and computed tomography (CT) in 5 (8.9%).

Of the 56 patients included, 34 underwent surgery within 2 weeks after the onset of stroke (early group), whereas surgery was deferred until after 2 weeks in the remaining 22 patients (delayed group). This study was approved by our institutional review board, which waived informed consent owing to the retrospective nature of this study.

1) Surgical techniques

A median sternotomy approach and conventional ascending aorta and bicaval cannulation were the usual strategy. Myocardial protection was achieved with antegrade and retrograde tepid blood cardioplegia. When infective endocarditis involved the aortic valve, the valve or root was replaced. When the mitral valve was involved, the decision to repair or replace was determined according to the degree of mitral apparatus preservation after resection of the infected tissue; that is, mitral valve replacement was performed only when the mitral tissue remaining after resection did not allow for repair surgery.

2) Postoperative management

Intravenous antimicrobial medications were continued for at least 4 weeks after surgery. If blood culture after surgery was positive for bacterial growth, intravenous antimicrobial medications were continued for at least 4 weeks after culture negativity. Antimicrobial regimens were continued or adjusted according to the results of bacterial culture and drug susceptibility of operative specimens. If no microorganism was cultured from either the blood or surgical specimens, called "culture-negative endocarditis", then the patient was treated with consultation with an infectious diseases specialist and the total duration of therapy was 4 to 6 weeks or more.

Patients who underwent valve repair or bioprosthetic valve implantation were routinely administered warfarin for 3~6 months postoperatively, with a target international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5~2.5. Further anticoagulation was based on the presence of thromboembolic risks and cardiac rhythm status in each patient. For patients with mechanical valve implantation, the target INR was 2.0~3.0, regardless of cardiac rhythm status.

3) Definitions

The primary endpoint of this study was defined as the composite of death and neurological aggravation, as determined clinically by neurologists, after surgery. The secondary endpoint was defined as the worsening of brain injury on CT and/or MRI. Worsening of injury included hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic infarction, increased size of infarction or hemorrhage, and development of new lesions.

4) Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD or medians and ranges. Differences in baseline characteristics between the early and delayed groups were compared using the t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Cumulative incidence rates of the composite outcome were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. All reported p-values are two-sided, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data documentation and statistical analysis were performed with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc.).

RESULTS

1) Demographic and clinical features

Of the 56 patients, 37 (66.1%) were male; mean age at surgery was 45.7±14.8 years. According to modified Duke criteria, 43 patients (76.8%) had definite and 13 (23.2%) had possible infective endocarditis, with the latter meeting 1 major and <3 minor criteria. Of these patients, 42 (75.0%) had ischemic and 14 (25.0%) had hemorrhagic events. The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Patients in the early group were more likely to have large (>1 cm) mobile vegetation, and were less likely to have undergone prosthetic valve implantation and have cerebral hemorrhage, than those in the delayed group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all patients

*p<0.05.

2) Preoperative neurological manifestations and microorganisms

Acute embolic infarction was observed in 26 patients, producing neurologic symptoms of dysarthria (n=6), sensory or motor loss (n=5), drowsiness (n=5), aphasia (n=3), visual loss (n=2), disorientation (n=2), memory impairment (n=1), dizziness (n=1), and syncope (n=1). Eleven patients had acute hemorrhage, presenting with symptoms of drowsiness (n=9), severe headache (n=1), and seizure (n=1). The remaining 19 patients had no symptoms of neurologic complications.

Multiple microemboli occurred in 12 (21.4%) patients, and intracranial mycotic aneurysms in 3 (5.4%). One patient (1.8%) had multiple brain abscesses caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

Microorganisms responsible for IE included Streptococcus in 20 patients (35.7%), Staphylococcus in 12 (21.4%), the HACEK group in 3 (5.4%, including Haemophilus in 1 and Cardiobacterium in 2), fungus in 1 (1.8%), and others in 5 (8.9%, including Enterococcus in 2, Klebsiella in 1, Brucella in 1, and Gamella in 1). The causative microorganisms could not be determined in 15 patients (26.8%).

3) Perioperative data and operative outcomes

The mean times from onset of acute septic embolic stroke to time of surgery were 3 days (range, 0~12 days) in the early surgery group and 20 days (range, 14~69 days) in the delayed surgery group. Aortic cross clamping time (88.2±59.4 min vs 80.0±37.8 min, p=0.568) and cardiopulmonary bypass time (124.6±83.4 min vs 121.8±51.6 min, p=0.891) were similar in the early and delayed groups. Surgical procedures included isolated mitral valve replacement in 22 patients, isolated mitral valve repair in 8, isolated aortic valve replacement in 15, combined aortic valve replacement and mitral valve replacement in 8, and Bentall operation in 3. There were two early deaths in the early surgery group (3.7%), with one patient dying 11 days after surgery due to a cerebral hemorrhage, and another dying 18 days after surgery due to a cerebral infarction.

Among the 54 survivors, 4 (7.1%) showed neurologic aggravation on clinical evaluations, 2 each in the early and delayed groups. Follow-up brain imaging was performed in 32 patients(57.1%). Changes in the postoperative neurologic status at discharge are summarized in Table 2. There were no significant differences in neurologic aggravation between the two groups, either clinically or radiologically.

Table 2.

Postoperative clinical and imaging evaluation of patient neurologic status

During a median follow-up of 61.7 months (range, 0.4~170.4 months), there were five late deaths, all in the early surgery group. Causes of late deaths were cerebral hemorrhage in one patient, unknown in one, and non cardiac-related events in three (one each from a traffic accident, aplastic anemia, and common bile duct cancer).

The overall mean 5-year neurologic aggravation-free survival rates were 79.1±7.0% in the early group and 90.9±6.1% in the delayed group (p=0.113) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Neurologic aggravation-free survival rate.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicated that early and delayed surgical interventions for IE were associated with similar survival and neurologic function in patients with acute septic embolic stroke. Neurologic deterioration was not influenced by the time interval from onset of acute septic embolic stroke to time of surgery. Although two patients in the early operation group died soon after surgery, at 11 and 18 days, the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant. Most patients with acute embolic stroke completely recovered from their neurologic symptoms without aggravation of neurologic imaging status.

Heparin anticoagulation during cardiopulmonary bypass has been regarded as at risk for secondary bleeding into ischemic regions, and low-pressure, non-pulsatile blood flow may accentuate the development of ischemic edema in the injured brain tissue [9]. After cerebral infarction, autoregulation of blood flow to the infarcted area is lost for 4~5 weeks. During this period, tissue perfusion is directly related to blood pressure and even a slight change of blood pressure can result in infarct extension and neurological deterioration [10]. These observations have led to suggestions that cardiac surgery be delayed until after the recovery of cerebral blood flow autoregulation, a period of 2 weeks after an ischemic stroke and 4 weeks after a hemorrhagic stroke [5,6]. Although there has been some evidence that supports this conventional management strategy [11,12], there have been no clinical studies to date in support of this delayed strategy for IE in patients with acute stroke [6]. We found that surgical intervention within 2 weeks is safe in IE patients with acute septic embolic stroke, and associated with outcomes similar to those of delayed surgery.

Despite advances in antibiotic treatment, this treatment alone cannot prevent the formation of mycotic aneurysms caused by septic emboli and does not decrease the incidence of neurologic complications in the overall IE patient population [2,13,14]. Because vegetations of IE are friable, removal of a potential source of emboli can prevent embolic stroke [3]. Patients with a vegetation with a diameter greater than 1 cm and high mobility have a significantly higher incidence of embolization, so that removal of the septic vegetation by early surgical intervention was effective in decreasing embolization in IE patients with large mobile vegetations [15-17]. However, the optimal timing of surgical intervention in IE patients with acute septic embolic stroke has remained unclear. Although early surgical intervention was previously shown to be safe in 15 IE patients with recent cardiogenic embolic stroke [10], that study population was limited to infarcted patients and the sample size was small, thus prompting our investigation.

1) Limitations of the study

This study is subject to the limitations inherent to a retrospective non-randomized study using observational data. The small number of patients included did not allow for adjustments for differences in baseline profiles between the two groups. Therefore, perioperative confounders, procedural bias, and detection bias may have affected our results. Another limitation was that only selected patients underwent follow-up MRI or CT. Prospective randomized studies including larger patient populations are therefore required.

CONCLUSION

Early and delayed surgeries for IE patients with acute embolic stroke were associated with similar clinical outcomes, as determined by mortality and neurologic function. Early surgical intervention may be a valuable option for a subset of patients at high risk of life-threatening septic embolism.

Footnotes

This paper has been presented as a poster at the 47th STS Annual Meeting in 2011.

References

- 1.Ziment I. Nervous system complications of bacterial endocarditis. Am J Med. 1969;47:593–607. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(69)90189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schold C, Earnest MP. Cerebral hemorrhage from a mycotic aneurysm developing during appropriate antibiotic therapy. Stroke. 1978;9:267–268. doi: 10.1161/01.str.9.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerner PI. Neurologic complications of infective endocarditis. Med Clin North Am. 1985;69:385–398. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruttmann E, Willeit J, Ulmer H, et al. Neurological outcome of septic cardioembolic stroke after infective endocarditis. Stroke. 2006;37:2094–2099. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000229894.28591.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsushita K, Kuriyama Y, Sawada T, et al. Hemorrhagic and ischemic cerebrovascular complications of active infective endocarditis of native valve. Eur Neurol. 1993;33:267–274. doi: 10.1159/000116952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eishi K, Kawazoe K, Kuriyama Y, Kitoh Y, Kawashima Y, Omae T. Surgical management of infective endocarditis associated with cerebral complications. Multi-center retrospective study in Japan. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:1745–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillinov AM, Shah RV, Curtis WE, et al. Valve replacement in patients with endocarditis and neurologic deficit. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1125–1130. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(96)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David TE. Surgical treatment of aortic valve endocarditis. In: Cohn LH, editor. Cardiac surgey in the adult. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill companies, Inc; 2008. pp. 949–955. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanter MC, Hart RG. Neurologic complications of infective endocarditis. Neurology. 1991;41:1015–1020. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.7.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zisbrod Z, Rose DM, Jacobowitz IJ, Kramer M, Acinapura AJ, Cunningham JN., Jr Results of open heart surgery in patients with recent cardiogenic embolic stroke and central nervous system dysfunction. Circulation. 1987;76:V109–V112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood MW, Wakim KG, Sayre GP, Millikan CH, Whisnant JP. Relationship between anticoagulants and hemorrhagic cerebral infarctions in experimental animals. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1958;79:390–396. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1958.02340040034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano JM, Trout HH, Kozloff L, Depalma RG. Timing of carotid artery endarterectomy after stroke. J Vasc Surg. 1985;2:250–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayer AS, Bolger AF, Taubert KA, et al. Diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis and its complications. Circulation. 1998;98:2936–2948. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.25.2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molinari GF, Smith L, Goldstein MN, et al. Pathogenesis of cerebral mycotic aneurysms. Neurology. 1973;23:325–332. doi: 10.1212/wnl.23.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DH, Kang DH, Lee MZ, et al. Impact of early surgery on embolic events in patients with infective endocarditis. Circulation. 2010;122(11 Suppl):S17–S22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thuny F, Di Salvo G, Belliard O, et al. Risk of embolism and death in infective endocarditis: prognostic valve of echocardiography: a prospective multicenter study. Circulation. 2005;112:69–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.493155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Salvo G, Habib G, Pergola V, et al. Echocardiography predicts embolic events in infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]