Abstract

Purpose

To explore multiple proton beam configurations for optimizing dosimetry and minimizing uncertainties for accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) and to compare the dosimetry of proton with that of photon radiotherapy for treatment of the same clinical volumes.

Methods and Materials

Proton treatment plans were created for 11 sequential patients treated with three-dimensional radiotherapy (3DCRT) photon APBI using passive scattering proton beams (PSPB) and were compared with clinically treated 3DCRT photon plans. Monte Carlo calculations were used to verify the accuracy of the proton dose calculation from the treatment planning system. The impact of range, motion, and setup uncertainty was evaluated with tangential vs. en face beams.

Results

Compared with 3DCRT photons, the absolute reduction of the mean of V100 (the volume receiving 100% of prescription dose), V90, V75, V50, and V20 for normal breast using protons are 3.4%, 8.6%, 11.8%, 17.9%, and 23.6%, respectively. For breast skin, with the similar V90 as 3DCRT photons, the proton plan significantly reduced V75, V50, V30, and V10. The proton plan also significantly reduced the dose to the lung and heart. Dose distributions from Monte Carlo simulations demonstrated minimal deviation from the treatment planning system. The tangential beam configuration showed significantly less dose fluctuation in the chest wall region but was more vulnerable to respiratory motion than that for the en face beams. Worst-case analysis demonstrated the robustness of designed proton beams with range and patient setup uncertainties.

Conclusions

APBI using multiple proton beams spares significantly more normal tissue, including nontarget breast and breast skin, than 3DCRT using photons. It is robust, considering the range and patient setup uncertainties.

Keywords: Accelerated partial breast irradiation, Protons, Monte Carlo, Three-dimensional radiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) is currently being intensively investigated as an alternative to whole-breast irradiation (WBI). Several methods for the delivery of APBI have been explored, including intracavitary brachytherapy with high-dose-rate balloon devices such as the Mammosite, Savi, or Contura; interstitial brachytherapy; and three-dimensional conformal external-beam radiotherapy (3DCRT) with photons (1–9). Given the rapidly increasing acceptance of APBI in the absence of randomized data comparing it with standard WBI, the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) and Radiation Therapy Oncology group (RTOG) have initiated a multi-institutional cooperative group trial (NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413) that is randomizing women with ductal carcinoma in situ Stage I or II breast cancer to conventional WBI or APBI using Mammosite, interstitial brachytherapy, or 3DCRT with photons.

The 3DCRT approach to APBI offers several distinct advantages over high-dose-rate brachytherapy using an implantable balloon. It is noninvasive and has greater dose homogeneity compared to brachytherapy techniques. In addition, it is routinely used by practicing radiation oncologists, and it is the most common approach selected by practitioners participating in the RTOG trial (10). However, 3DCRT using photons or a combination of photons and electrons has less dose conformity to the target, and its greater setup uncertainty results in larger volumes of irradiated normal tissues than other techniques, such as brachytherapy. To retain the advantages of 3DCRT while improving dose conformity, APBI with protons was investigated (11–16). Compared with photons, protons have fundamental physical advantages that potentially reduce dose to nontarget tissue, and their use is less expensive than the same treatment regimen with high-dose-rate applicators such as the Mammosite (17). We used Monte Carlo simulation and worst-case analysis (WCA) to examine the robustness of the documented treatment plans demonstrating reduced dose to nontarget tissues. Several prior dosimetric investigations have shown significant reduction of irradiated nontarget breast tissue and exceptional lung and heart sparing using passive scattering proton beams (PSPB) for APBI compared with 3DCRT (11, 13–16). However, the limited initial clinical reports using PSPB for APBI resulted in more acute skin toxicity than does 3DCRT, and also some rib tenderness and fractures (12). Herein, we further investigated distinct planning approaches using multiple proton beams to distribute dose to skin and achieve comparable skin dose to once-daily radiation with standard fractionation and also approaches to minimize rib dose. The impact of motion was further examined by treatment approach, highlighting the need to select beams carefully based on patient-specific and tumor-specific factors.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Computed tomography, treatment planning, and dose distribution

The computed tomography (CT) datasets from 10 APBI patients treated at our institution on NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413 using 3DCRT with photons, and 1 APBI patient treated off protocol with 3DCRT using photons and electrons (not permitted on the randomized protocol), were retrospectively selected and replanned using PSPB. The CT images were obtained at 2.5-mm slice thickness through the region of interest. All patients were in the supine position, with the ipsilateral upper extremity abducted and the head rotated slightly toward the contralateral side. The definition of clinical target volume (CTV) followed NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413 guidelines (i.e., uniformly expanding lumpectomy 1.5 cm but no shallower than breast skin and no deeper than the anterior chest wall and pectoralis muscles). In addition to all the normal structures defined in NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413, the breast skin and ipsilateral normal (nontarget) breast were contoured for each patient. Breast skin volume was defined as a 5-mm strip from the patient’s ipsilateral breast surface outline to 5 mm deeper. The 5-mm thickness of skin is chosen to include the three layers of skin (epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis) (18) and is also adopted in head and neck IMRT to achieve skin dose reduction (19). Ipsilateral normal breast was defined as the ipsilateral breast volume (i.e., breast tissue contained within standard WBI fields) excluding CTV.

The 3DCRT plans were designed using the Pinnacle (Version 7.6c; Philips Medical System, Milpitas, CA) treatment planning system (TPS). The three to five coplanar and noncoplanar beams using 6-MV and 18-MV photons were generated based on patient-specific anatomy and target location. A multileaf collimator was used to manually optimize the plan to maximize the planning target volume (PTV) coverage and minimize normal tissue doses. For the mixed-modality plan, multiphoton beams were designed with an en face electron beam. The target dose and the specified normal tissue constraints followed the NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413 protocol. All 3DCRT plans were reviewed and approved by the seven breast cancer radiation oncologists and used for patient treatment.

The proton plans using PSPB were designed using the Eclipse (Eclipse Proton, version 8.1; Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) treatment planning system. The prescription dose was 38.5 Gy (RBE) for 10 fractions. [Gy (RBE) denotes relative biological effectiveness (RBE)-corrected dose units] Three to four beams were used for the proton plans in which 90% prescription dose covered more than 99% CTV and 90% beam-specific PTV. The proximal and distal margins of the beams were designed using Moyer’s formula (20) as currently in clinical practice, and radial margins were designed to cover a 1-cm expansion of the CTV (i.e., accounts for the lateral setup uncertainties of breast irradiation using protons, following the definition in NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413 for PTV_eval). Each beam entrance was designed to have minimal overlap on the patient surface to reduce the skin toxicity.

The dose–volume histograms (DVHs) for the CTV and normal structures were calculated and collected for both PSPB and 3DCRT with photons as follows: the percentage volume receiving greater than or equal to 90% of prescription dose (V90) for CTV and PTV_eval; V100, V90, V75, V50, and V20 for nontarget breast volume; V90, V75, V50, V30, and V10 for breast skin; the maximum dose of heart, contralateral breast, and lung; the mean dose, V5Gy (percentage of volume receiving dose greater than or equal to 5 Gy), V10Gy, and V20Gy for ipsilateral lung. To explore the normal structures sparing for PSPB, especially skin sparing, the DVHs of all normal structures and targets and for dose distributions in PSPB were compared with those from 3DCRT with photons. A two-tailed pairwise Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for statistical analysis.

Monte Carlo calculation

Because the accuracy of the proton dose calculation from the TPS was a particular concern, especially the surface (or skin) dose, Monte Carlo simulations were performed for proton plans of a patient who was randomly selected from the 11 patients. The Monte Carlo Proton Radiotherapy Treatment Planning system (MCPRTP) (21) was used for the Monte Carlo simulations. MCPRTP has been used in previous proton therapy studies (22) and includes the Monte Carlo N-Particle eXtended code version 2.6b (23) with parallel processing. Details of MCPRTP have been reported previously (24).

The 3D Gamma evaluation method developed by Low et al. (25) was adapted to quantitatively compare the dose distributions calculated by the TPS and Monte Carlo simulation. The recommended distance-to-agreement criterion (i.e., 3 mm) and dose difference criterion (3%) (25) was used to calculate γ. The regions where γ>1 are the regions of more significant disagreement. The γ volume histogram was also calculated for the selected structures and the whole body. The percentage volume of the structure with γ>1 less than 3% was considered to have no significant dose difference between two calculations for the corresponding structure. The smaller the volume with γ>1 was, the better the two calculations agreed with each other.

Beam angle selection and evaluation

In this study, the proton plans were designed to use multiple beam configurations, which were individualized based on the patient-specific anatomy and target location. When the target volume was adjacent to the chest wall, the tangential beams from the middle, lateral, superior, or inferior direction were considered to minimize lung and rib irradiation. When the target volume was located superficially, the en face beam directions (i.e., the beam directly toward the lung and the chest wall) combined with tangential beam directions were used to achieve the best normal tissue sparing.

To illustrate the effects of range uncertainties for PSPB from different directions (i.e., the tangential directions and en face directions), 1 patient with the target attached to the chest wall was selected from 11 patients. The proton plan was initially designed to use three beams from tangential direction. We modified one of the three beams to aim toward the chest wall and lung. The dose distributions of “range overshoot plan” were calculated with the stopping power ratio to CT number decreasing 3.5% (which translates to 3.5% overshoot in the beam direction). The dose difference distributions between the original plan and the range overshoot plan were calculated (i.e., dose from range overshoot plan subtracting dose from original plan) and compared between the plan with tangential beams and the plan with one beam toward the chest wall.

Two CT datasets (i.e., free-breathing CT and deep-breath-hold CT) from 1 of 11 patients were used to demonstrate the effects of respiratory motion to PSPB with different beam directions. The single proton beam from tangential direction and en face direction was used to design two plans, respectively, on free-breathing CT and then applied to the breath-hold CT. The dose distributions and DVHs on two CT datasets for each plan were compared to show the dosimetric effects of respiratory motion for PSPB with different beam directions.

The WCA method (26) was also used to analyze the uncertainties of patient setup and CT numbers for the multiple proton beam configurations. The dose distributions were calculated in eight scenarios: isocenter shift 5 mm in anterior, posterior, superior, inferior, right, and left direction (i.e., simulate the patient setup uncertainties), and stopping power ratio to CT numbers increase and decrease 3.5% (i.e., simulated the range uncertainties) (20). The final WCA dose distribution was constructed as selecting the lowest dose inside CTV and highest dose outside CTV among eight dose distributions (i.e., the worst dose distribution).

RESULTS

Dose distributions

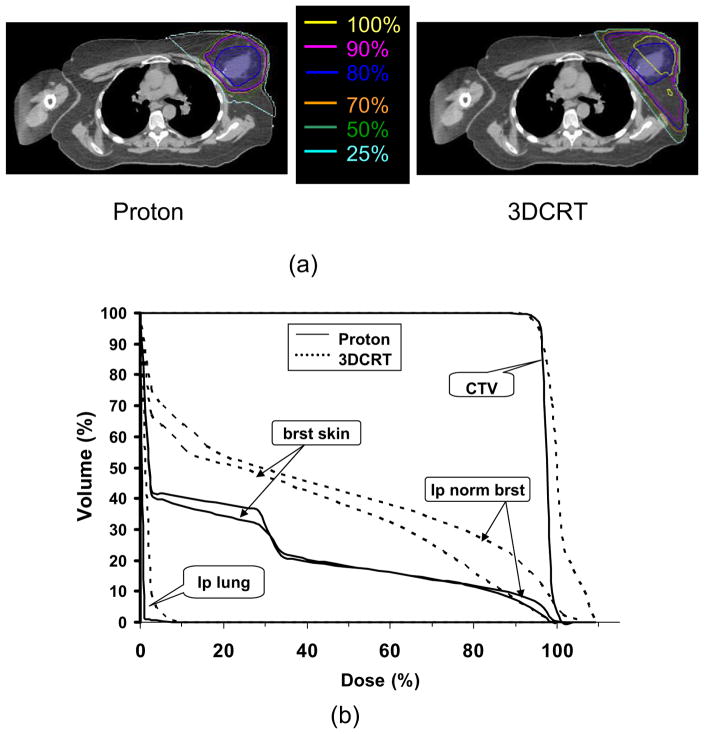

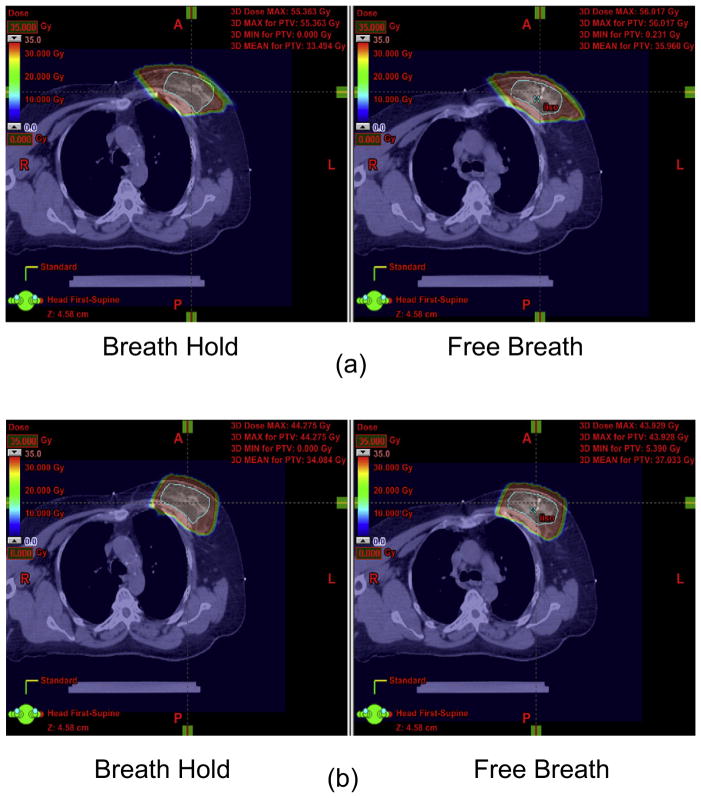

The table lists the dosimetric comparison for specific normal structures (i.e., ipsilateral normal breast, contralateral breast, lungs, heart, and breast skin) and treatment target (i.e., CTV and PTV_eval) between proton and 3DCRT plans for 11 patients. With the comparable prescription doses coverage for the treatment target (i.e., CTV and PTV_eval) for proton and 3DCRT plans, the proton plans were superior to the 3DCRT plans. The average V20, V50, V75, V90, and V100 of the ipsilateral normal breast were 38.8%, 26.9%, 19.3%, 12.4%, and 2.8%, respectively, for proton plans; the absolute reduction about 23.6%, 17.9%, 11.8%, 8.6%, and 3.4%, respectively, from that for 3DCRT with photons. For breast skin, in comparison with 3DCRT plans, protons significantly reduced the average V10, V30, V50, and V75 (i.e., 47.3%, 39.8%, 27.8%, and 18.9%, respectively) by about 12.3%, 11.8%, 12.4%, and 3.8%, respectively. The irradiated volume of breast skin for V90 was comparable (p = 0.859) between proton and 3DCRT plans. For all other critical structures, the proton plans significantly reduced doses and irradiated volumes compared with 3DCRT. Typical dose distributions and DVHs of proton and 3DCRT photon plans for 1 of the study patients are presented in Fig. 1. With the similar target dose coverage for both plans, protons delivered significantly less dose to the normal breast tissue and lung than did 3DCRT. For the skin, in low-dose and medium-dose regions, protons spared more skin than did 3DCRT. In high-dose regions, the skin doses were comparable between two modalities. It might be argued that the addition of electrons to photon planning (not permitted on the RTOG/NSABP protocol) would negate the advantage of protons because of the greater similarities between proton and electron dosimetry at shallow depths. For this reason, an off-protocol plan using photons and electrons was compared with a plan using protons, which still provided better normal tissue sparing. The V20, V50, V75, V90, and V100 of the ipsilateral normal breast were 42.7%, 30.7%, 20.7%, 12.4%, and 0.25%, respectively, for the proton plan, an absolute reduction of 15%, 9%, 5.4%, 2.4%, and 1.3%, respectively, from that for 3DCRT with photons and electrons. Although this indicates that protons can provide superior normal tissue sparing compared with mixed photon electron planning, the magnitude and likelihood of this benefit is clearly related to the geometry of the cavity and breast, and further studies are warranted to determine what criteria may predict for a truly meaningful advantage using protons when electrons are available.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of (a) dose distributions and (b) dose–volume histograms between proton and 3DCRT treatment plans for 1 of the study patients. 3DCRT = three-dimensional radiotherapy; CTV = clinical target volume; brat skin = breast skin; lp normal brat = ipsilateral normal breast; lp lung = ipsilateral lung.

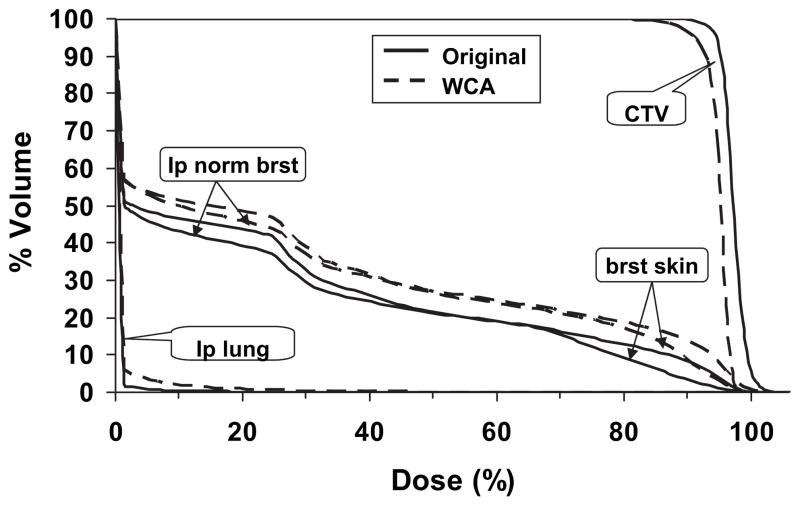

Given the greater sensitivity of proton planning to setup variation and range uncertainties, the DVHs of the original vs. the worst-case plan for one randomly selected proton plan (Fig. 2) demonstrated the DVHs of normal structures remained within dose constraints. For the target, over 90% of the CTV covered by 95% of the prescription dose in the worst-case scenario.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of dose–volume histograms between original proton plan and plan from WCA for 1 randomly selected patient. WCA = worst-case analysis; CTV = clinical target volume; brat skin = breast skin; lp normal brat = ipsilateral normal breast; lp lung = ipsilateral lung.

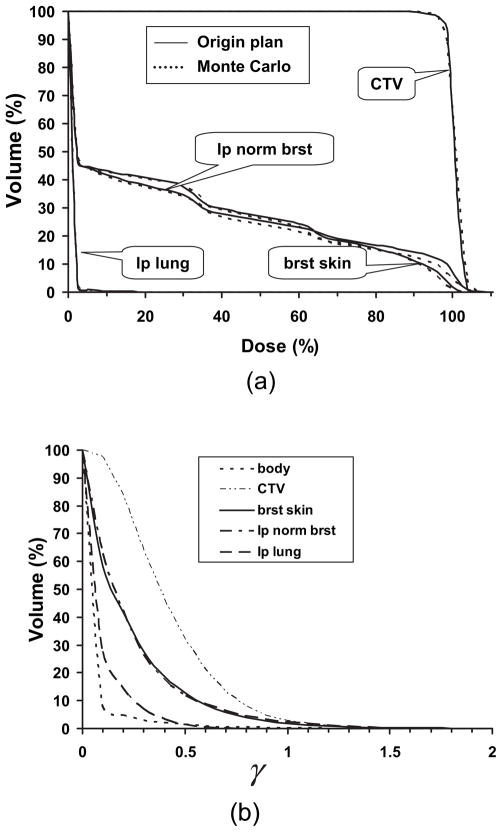

Comparison for proton dose from TPS and Monte Carlo

Figure 3a shows the DVHs for one proton plan by the TPS and the MCPRTP. The DVHs calculated from the TPS agreed with those from the MCPRTP very well. The γ volume histogram for different structures and whole body is presented in Fig. 3b. The x axis represents the γ value, and the y axis represents the percentage volume of the structure with γ greater than or equal to the certain value. The percentages of volume with γ>1 for CTV, ipsilateral normal breast, breast skin, and whole body were 2.81%, 2.52%, 1.92%, and 0.22%, respectively. All the values were less than 3%, which demonstrated that proton dose calculated from TPS had no significant difference from MCPRTP including surface area such as breast skin. This finding provided evidence that dose distributions calculated by the TPS were accurate.

Fig. 3.

(a) Comparison of dose–volume histograms between treatment planning system and Monte Carlo calculations for one randomly selected proton plan. (b) The γ volume histogram of different structures for comparison of dose distribution between treatment planning system and Monte Carlo calculations shown in (a). CTV = clinical target volume; brat skin = breast skin; lp normal brat = ipsilateral normal breast; lp lung = ipsilateral lung.

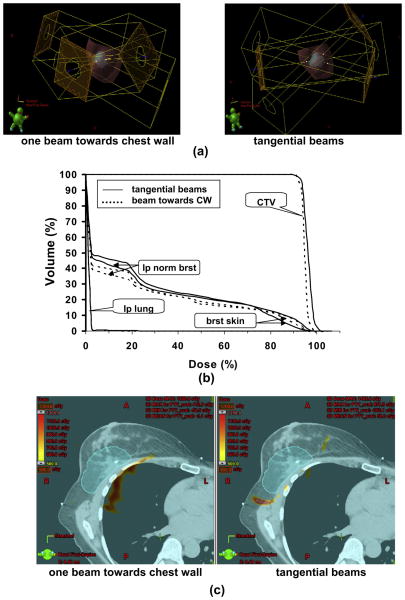

Pros and cons of tangential vs. en face proton beams

The 3D renderings of the beam orientations, for a representative proton plan with three tangential beams vs. one in which one tangential beam was oriented directly toward the chest wall, were compared to examine the dose to normal tissue and the impact of range uncertainty as a function of beam orientation Fig. 4a). Figure 4b shows the DVHs for both configurations shown in Fig. 4a. The plan with a beam toward the chest wall spared more ipsilateral normal breast tissue than that with the tangential beam configurations in low-dose and medium-dose regions. In high-dose regions, the sparing of ipsilateral normal breast was similar between the two configurations. For breast skin, in the high-dose region, the plan with tangential beams spared more skin than that with a beam toward the chest wall and vice versa in low and medium dose region. Figure 4c shows the dose difference distributions of the original plan and the range overshoot plan for two plans with different beam configurations shown in Fig. 4. There were the regions near the chest wall with >10 Gy dose difference for the plan with a beam toward the chest wall but few regions with >5 Gy dose difference near the chest wall for the plan with tangential beam orientations.

Fig. 4.

Impact of range overshoot on the chest wall and lung for protons with different beam configurations. (a) Beam configurations of three tangential beams and three beams with one beam toward chest wall (CW). (b) Comparison of dose–volume histograms between two beam configurations shown in (a). (c) Dose difference distributions of original plan and range overshoot plan for tangential beam configurations and beam configurations with one beam toward CW. The red color wash displays the area with the dose difference over 10 Gy. CTV = clinical target volume; brat skin = breast skin; lp normal brat = ipsilateral normal breast; lp lung = ipsilateral lung.

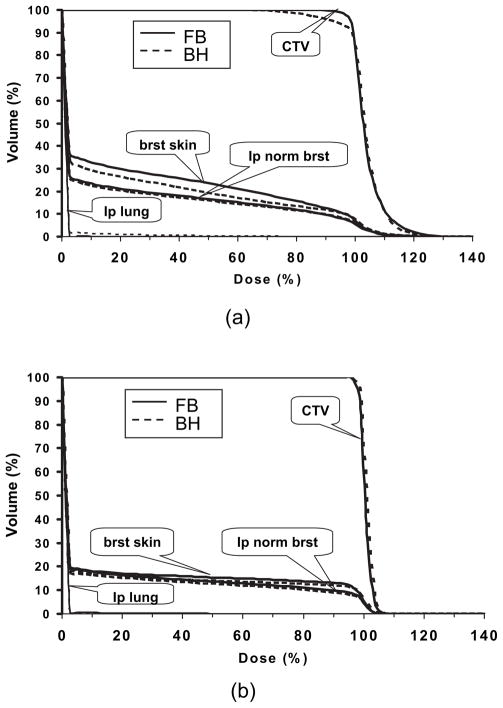

The impact of motion was examined using the most extreme case: deep inspiration breath-hold. For this scan, the patient was asked to take a deep breath and hold it. The dose distributions on free-breathing CT and breath-hold CT for the plan using the single tangential beam and the plan using the single en face beam are shown in Fig. 5a and b, respectively. The tangential plan was more sensitive to breathing motion with underdosage to the CTV and greater dose to the ipsilateral lung occurring using tangential beam during breath-hold, but not for the plan using en face beam. Figure 6 shows the DVHs based on free-breath CT and breath-hold CT for the plan using tangential beam (Fig. 6a) and the plan using en face beam (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 5.

Dose distributions on free-breathing computed tomography (right) and breath-hold computed tomography (left) for (a) tangential beam configuration and (b) en face beam configuration. The red color wash displays 90% of prescription dose.

Fig. 6.

Dose–volume histograms on free-breathing (FB) computed tomography (solid line) and breath-hold (BH) computed tomography (dashed line) for (a) tangential beam configuration and (b) en face beam configuration. CTV = clinical target volume; brat skin = breast skin; lp normal brat = ipsilateral normal breast; lp lung = ipsilateral lung.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated significant dosimetric advantages of the proton plans using multiple beam configurations compared with 3DCRT for patients treated with external-beam APBI. Gamma analysis showed good dose agreement between Monte Carlo calculation and TPS, including skin dose. We were able to obtain a more optimal dose distribution with protons while achieving a skin dose that was comparable with once-daily radiation with standard fraction size. This skin dose would be unlikely to lead to greater toxicity than would 3DCRT with photons. Multiple beam arrangements and numbers of beams were explored to optimize the dosimetry and minimize uncertainties that might have contributed to previously reported toxicities related to APBI (12). Although comparison with a historical control might introduce bias such that the cases planned for the study were optimized more carefully, we believe that using historical cases that were planned for treatment to meet planning criteria for the prospective RTOG trial minimize this. The photon plans were all critically reviewed by seven breast cancer radiation oncologists as a part of the routine quality assurance process before treatment. The proton plans were reviewed and optimized by a clinical proton physicist who was blinded to the photon planning for these cases.

The dosimetric results of our study agree with the reports by Kozak et al. (11) and Bush et al. (15), where the proton plans deliver significantly less dose to the normal structures than 3DCRT with photons. In addition to these published reports, the current data highlight the pros and cons of distinct planning approaches to address clinical toxicities reported thus far and demonstrate the robustness of distinct planning approaches using multiple approaches. For comparison with photon plans, the CTV margins used for all plans were defined as per NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413 protocol, a 1.5-cm extension from the lumpectomy cavity. Inasmuch as the proton and the photon-electron are different modalities, the PTV defined originally for photon-electron radiotherapy is not appropriate for proton radiotherapy, in which beam-specific PTVs are required. However, the radial PTV proton margin was dictated by the RTOG/NSABP protocol as a 1-cm extension from the CTV. The resulting target was therefore larger than that in reports by Kozak et al. (12) and Bush et al. (15) and relatively nearer the patient surface. This resulted in less absolute skin sparing for high dose region in our study than that reported by Bush et al. (15), and less absolute normal breast tissue sparing than that reported by Kozak et al. (12) and Bush et al. (15). Certainly, in clinical practice with image-guided setup and proper immobilization, the radial PTV margin might be reduced if the measured data demonstrate smaller achievable set-up uncertainty. Further reduction of the PTV margin when appropriate will significantly increase the sparing of normal breast tissue and skin for proton plans. We further note that off-protocol treatment with protons would likely be optimized by prescribing the intended dose of 34 Gy (RBE) in 10 fractions to the clinical target volume rather than the protocol-dictated prescribed dose of 38.5 Gy in 10 fractions to the isocenter (a prescribing convention dictated by the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements, which results generally in a delivered dose of 34 Gy to the intended volume).

Few data are available in the literature that evaluate the skin doses using PSPB (15). However, the initial clinical experience using PSPB resulted in more severe acute skin toxicities than 3DCRT (12). In this study, the DVH comparison for skin dose between PSPB and 3DCRT was investigated. For V90, the skin dose for proton plans was statistically comparable with that for 3DCRT in the dose region despite the superficial location of the targets. To have sufficient dose coverage for targets, multiple beams overlapped in the surface region anterior to the target, which mainly contributed to the high dose to breast skin and might still carry a risk for skin toxicity. For the patients with deeper targets, the skin dose from proton plans in a high-dose region will decrease significantly using proposed beam configurations. In the region of dose less than 90% prescription dose, the skin dose from proposed proton plan was significantly less than that from 3DCRT with photons. In addition, comparison of dose distributions and DVHs between three-beam configurations and four-beam configurations for 1 patient were examined (data not shown). There was no significant dosimetric difference between these two configurations. Therefore, there was no disadvantage to using four-beam plans, such that two beams could be delivered alternately every fraction, thus limiting the dose to any portion of the skin not common to multiple beams to less than 2 Gy per fraction.

The pros and cons of each beam orientation need to be understood and considered relative to the geometry and clinical factors for each individual patient. As shown in Figure 4, ipsilateral nontarget breast and breast skin sparing was improved in the high-dose region compared to that with tangential beam directions through the use of an en face beam. This was because the beam toward the chest wall was appositional to the target and passed through less breast tissue and skin than the tangential beam, which resulted in better sparing of breast tissue and skin in low-dose and medium-dose regions. The high dose was confined around the target and with only one beam oriented toward the chest wall might not affect it very much, which resulted in comparable sparing for the ipsilateral normal breast in the high-dose region between two beam configurations. For breast skin, the surface overlap of the beams’ entrance for the plan with a beam toward the chest wall was larger than in the plan with tangential beams, which resulted in the worse sparing of breast skin in the high-dose region for a plan with a beam toward the chest wall. En face beams are subject to range uncertainty, potentially leading to excess rib and lung dose when the target is close to the chest wall, but they are less sensitive to breathing and motion (including positioning errors), which may potentially lead to greater normal tissue dose and failure to cover the target. Inasmuch as the range of the proton beam is mainly related to the depth of the target, the target, or motion of normal structures along the beam direction, such as en face beam, has the minimal dosimetric effects. As the target or normal structures motion cross the beam direction, as it does with the tangential beam, the target could move to the penumbra or out of the beam, or the normal structures could move into the beam, which could result in underdose of to target or overdose to the normal structures. Furthermore, such motion of tissue perpendicular to tangential beam axes can significantly change the radiologic path-length and thus compromise the depth of proton penetration. Of course, the deep breath-hold comparison demonstrated here represented the worst-case scenario regarding breathing motion. The respiratory motion of free breathing was considerably smaller and might be negligible for many free-breathing patients in a supine position with the ipsilateral shoulder abducted and the chest fully extended. Measurements of respiratory motion using four-dimensional CT and setup variability are warranted before using tangential beam arrangements.

CONCLUSIONS

Accelerated partial breast irradiation using protons provides a homogenous conformal treatment approach that is superior to 3DCRT with photons. It is also robust regarding motion and range uncertainties and affords the benefits of a noninvasive APBI approach. Tailoring treatment planning approaches has the potential to minimize the risks of APBI reported in the existing dosimetric and clinical literature (11, 12, 14, 15). With similar target coverage and skin dose in the hypothesized toxicity dose region, the proton plans showed significant advantage for normal tissue sparing compared with 3DCRT with photons. The advantages and disadvantages of each beam configuration should be considered with the patient-specific geometry in each case.

Table.

Summary of the statistics of DVHs for proton and 3D-CRT plans of 11 patients

| Statistic | Proton: mean (min–max) | 3D CRT: mean (min–max) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTV_Eval | |||

| V90 (%) | 96.4% (92.0%–99.2%) | 96.9% (92.0%–99.4%) | 0.109 |

| CTV | |||

| V90 (%) | 99.7% (98.0%–100%) | 99.5% (97.7%–100%) | 0.478 |

| Ipsilateral normal breast | |||

| V100 (%) | 2.8% (0.0%–8.5%) | 5.6% (0.8%–23.3%) | 0.007 |

| V90 (%) | 12.4% (7.0% –26.8%) | 19.4% (9.2%–47.5%) | 0.001 |

| V75 (%) | 19.3% (10.9%–36.4%) | 30.0% (21.4%–58.7%) | 0.001 |

| V50 (%) | 26.9% (13.8%–47.8%) | 43.5% (28.6%–68.8%) | 0.001 |

| V20 (%) | 38.8% (26.5%–57.4%) | 60.2% (39.1%–86.0%) | 0.001 |

| Contralateral breast | |||

| Max dose (Gy) | 0.12 (0.00–0.82) | 2.20 (0.19–10.30) | 0.001 |

| Ipsilateral lung | |||

| Mean dose (Gy) | 0.84 (0.00–1.90) | 3.07 (0.39–6.06) | 0.001 |

| V5Gy (%) | 5.3% (0.1%–12.4%) | 18.4% (0.0%–47.0%) | 0.002 |

| V10Gy (%) | 2.9% (0.0%–7.6%) | 8.8% (0.0%–17.0%) | 0.004 |

| V20Gy (%) | 1.4% (0.0%–4.2%) | 3.5% (0.0%–9.0%) | 0.028 |

| Contralateral lung | |||

| Mean dose (Gy) | 0.01 (0.00–0.07) | 0.13 (0.04–0.40) | 0.001 |

| Heart | |||

| Max dose (Gy) | 6.0 (0.00–31.65) | 9.40 (0.78–37.0) | 0.001 |

| Breast skin | |||

| V90 (%) | 11.5% (2.4%–21.1%) | 7.6% (1.5%–22.5%) | 0.859 |

| V75 (%) | 18.9% (10.0%–38.2%) | 22.7% (10.6%–52.2%) | 0.019 |

| V50 (%) | 27.8% (17.8%–52.4%) | 40.2% (27.9%–73.8%) | 0.002 |

| V30 (%) | 39.8% (28.1%–59.3%) | 52.6% (37.3%–86.0% | 0.001 |

| V10 (%) | 47.3% (32.6%–67.6%) | 69.5%(47.8%–92.2%) | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: DVSs = dose–volume histograms; 3D-CRT = three-dimensional radiotherapy; PTV_eval = evaluated planning target volume; CTV = clinical target volume; max = maximum; min = minimum.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

References

- 1.Bensaleh S, Bezak E, Borg M. Review of MammoSite brachy-therapy: Advantages, disadvantages and clinical outcomes. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:487–494. doi: 10.1080/02841860802537916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orecchia R, Veronesi U. Intraoperative electrons. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2005;15:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pignol JP, Rakovitch E, Keller BM, et al. Tolerance and acceptance results of a palladium 103 permanent breast seed implant phase I/II study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:1482–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polgar C, Strnad V, Major T. Brachytherapy for partial breast irradiation: The European experience. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2005;15:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaidya JS, Tobias JS, Baum M, et al. TARGeted intraoperative radioTherapy (TARGIT): An innovative approach to partial-breast irradiation. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2005;15:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vicini FA, Arthur DW. Breast brachytherapy: North American experience. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2005;15:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wazer DE. Point: Brachytherapy for accelerated partial breast irradiation. Brachytherapy. 2009;8:181–183. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusthoven KE, Carter DL, Howell K, et al. Accelerated partial-breast intensity-modulated radiotherapy results in improved dose distribution when compared with three-dimensional treatment-planning techniques. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taghian AG, Kozak KR, Doppke KP, et al. Initial dosimetric experience using simple three dimensional conformal external-beam accelerated partial-breast irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1092–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vivini F Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. [Date accessed July 24, 2010.];NSABP B-39/RTOG 0413 protocol. Available at: www.RTOG.org.

- 11.Kozak KR, Katz A, Adams J, et al. Dosimetric comparison of proton and photon three dimensional, conformal, external beam accelerated partial breast irradiation techniques. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1572–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozak KR, Smith BL, Adams J, et al. Accelerated partial-breast irradiation using proton beams: Initial clinical experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon SH, Shin KH, Kim TH, et al. Dosimetric comparison of four different external beam partial breast irradiation techniques: Three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy, intensity modulated radiotherapy, helical tomotherapy, and proton beam therapy. Radiother Oncol. 2009;90:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taghian AG, Kozak KR, Katz A, et al. Accelerated partial breast irradiation using proton beams: Initial dosimetric experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1404–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bush DA, Slater JD, Garberoglio C, et al. A technique of partial breast irradiation utilizing proton beam radiotherapy: Comparison with conformal X-ray therapy. Cancer J. 2007;13:114–118. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318046354b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fogliata A, Bolsi A, Cozzi L. Critical appraisal of treatment techniques based on conventional photon beams, intensity modulated photon beams and proton beams for therapy of intact breast. Radiother Oncol. 2002;62:137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald SM, Taghian AG. Is it time to use protons for breast cancer? Cancer J. 2007;13:84–86. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318053cdb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saibishkumar EP, Mackenzie MA, Severin D, et al. Skin-sparing radiation using intensity modulated radiotherapy after conservative surgery in early-stage breast cancer: A planning study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee N, Chuang C, Quivey JM, et al. Skin toxicity due to intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head-and-neck carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:630–637. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02756-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moyers MF, Miller DW, Bush DA, et al. Methodologies and tools for proton beam design for lung tumors. Int J Radia Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:1429–1438. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newhauser W, Fontenot J, Zheng YS, et al. Monte Carlo simulations for configuring and testing an analytical proton dose-calculation algorithm. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:4569–4584. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/15/014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taddei PJ, Mirkovic D, Fontenot JD, et al. Stray radiation dose and second cancer risk for a pediatric patient receiving cranio-spinal irradiation with proton beams. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2259–2275. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/8/001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelowitz DB. MCNPXTM User’s manual, version 2.6.0. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng Y, Newhauser W, Fontenot J, et al. Monte Carlo study of neutron dose equivalent during passive scattering proton therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:4481–4496. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/15/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Low DA, Harms WB, Mutic S, et al. A technique for the quantitative evaluation of dose distributions. Med Phys. 1998;25:656–661. doi: 10.1118/1.598248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lomax AJ, Pedroni E, Rutz H, et al. The clinical potential of intensity modulated proton therapy. Z Med Phys. 2004;14:147–152. doi: 10.1078/0939-3889-00217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]