Abstract

Mechanistic models of glucose stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) established in minimal media in vitro, may not accurately describe the complexity of coupling metabolism with insulin secretion that occurs in vivo. As a first approximation, we have evaluated metabolic pathways in a typical growth media, DMEM as a surrogate in vivo medium, for comparison to metabolic fluxes observed under the typical experimental conditions using the simple salt-buffer of KRB. Changes in metabolism in response to glucose and amino acids and coupling to insulin secretion were measured in INS-1 832/13 cells. Media effects on mitochondrial function and the coupling efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation were determined by fluorometrically measured oxygen consumption rates (OCR) combined with 31P-NMR measured rates of ATP synthesis. Substrate preferences and pathways into the TCA cycle, and the synthesis of mitochondrial 2nd messengers by anaplerosis were determined by 13C-NMR isotopomer analysis of the fate of [U-13C]glucose metabolism.

Despite similar incremental increases in insulin secretion, the changes of OCR in response to increasing glucose from 2.5 to 15 mM were blunted in DMEM relative to KRB. Basal and stimulated rates of insulin secretion rates were consistently higher in DMEM, while ATP synthesis rates were identical in both DMEM and KRB, suggesting greater mitochondrial uncoupling in DMEM. The relative rates of anaplerosis, and hence synthesis and export of 2nd messengers from the mitochondria were found to be similar in DMEM to those in KRB. And, the correlation of total PC flux with insulin secretion rates in DMEM was found to be congruous with the correlation in KRB. Together, these results suggest that signaling mechanisms associated with both TCA cycle flux and with anaplerotic flux, but not ATP production, may be responsible for the enhanced rates of insulin secretion in more complex, and physiologically-relevant media.

Keywords: Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, anaplerosis, mitochondrial metabolism, INS-1, beta-cells, second messengers, ATP synthesis, substrate cycling

Introduction

Mechanistic models of glucose stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) established in minimal media in vitro, may not accurately describe the complexity of coupling metabolism with insulin secretion that occurs in vivo. Central to the mechanism of nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion is that increases in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation lead to increases in cytosolic ATP concentrations that initiate the cascade of events leading to insulin exocytosis [1]. As a first approximation, one would predict that changes in the rate of oxidative phosphorylation should be directly proportional to changes in oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and insulin secretion. Surprisingly though, the correlation between OCR (and presumably oxidative phosphorylation) and insulin secretion has been shown to depend upon the complexity of the media [2]. In mouse βHC9 cells, Papas and Jerema [2] observed the change in insulin secretion was proportional to the change in OCR, when the cells were stimulated with 15mM glucose in minimal media (PBS). These results are in agreement with the predictions of the role of mitochondrial ATP production leading to closure of the KATP channel to increase Ca2+ and trigger insulin exocytosis. However, despite a 2-fold increase in insulin secretion in response to 15mM glucose, there was no observed change in OCR, and presumably oxidative phosphorylation, in more nutrient-complex Dubelco’s Minimal Eagle Media (DMEM) buffer.

Possible explanations to account for this anomalous disassociation between insulin secretion rates and OCR include media-associated changes in 1.) mitochondrial coupling of ATP synthesis with flux of the electron transport chain and oxygen consumption, 2.) anaplerosis-dependant increases in the export of mitochondria 2nd messengers, or possibly 3.) the induction of other cytosolic signaling intermediates or pathways that are coupled to insulin secretion.

In order to shed light on which of these potential mechanisms may account for the disassociation of nutrient-stimulated insulin secretion from OCR and possibly oxidative phosphorylation, we evaluated the correlation of fuel-stimulated insulin secretion with 1.) the putative uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, and 2.) the rates of mitochondrial anaplerosis. We used 31P-NMR to measure rates of ATP synthesis and to measure the concentrations of ATP and intracellular Pi that occurred upon stimulating insulin secretion by increasing glucose from 2.5 mM to 15 mM [3, 4]. OCRs were measured under identical conditions fluorometrically in a sealed, stirred bioreactor [2, 5]. To assess the possibility that mitochondrial anaplerotic flux and the synthesis of putative 2nd messengers may provide an explanation for the disconnect between oxygen consumption and insulin secretion in the complex media, we used a 13C-isotopomer approach to determine pathways of anaplerosis in response to the secretagogues of glucose, glutamine and leucine [6, 7]. The studies described herein evaluated these correlations using the rat insulinoma cell line INS-1 832/13 [8] in the physiologically-complex DMEM for comparison to results obtained in KRB.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Initial stocks of clonal INS-1 832/13 cells, overexpressing the human insulin gene, were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. Christopher B. Newgard (Duke University School of Medicine) [8]. INS-1 cells were cultured as monolayers in RPMI-1640 as previously described [6].

Basal metabolic parameters were measured at 2.5 mM glucose, in order to maintain stable intracellular ATP concentrations, while avoiding nutrient-starvation. In preliminary NMR experiments, we observed that culture of the cells at 0 mM glucose in KRB led to a rapid fall in ATP concentrations and loss of cell viability. The addition of glucose to these ATP-deficient cells then led to a burst of ATP production to re-establish more physiologically-sustainable concentrations of ATP. In contrast, with 2.5 mM glucose, ATP concentrations remained stable and cell viability was maintained during a 24-hour perfusion.

13C-Isotopomer studies of anaplerotic pathways

Flux of metabolites via the anaplerotic pathways of pyruvate carboxylase (PC) or glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), relative to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, were determined by analysis and modeling of the 13C-isotopomer pattern in glutamate as previously described [6, 7]. Briefly, basal conditions were established with a 2 hr pre-incubation in DMEM with a sub-stimulatory concentration of glucose (2.5 mM). The cells were then washed with PBS, and then incubated for an additional 2 hrs in DMEM with [U-13C] glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Miamisburg, OH, 99% 13C, 2.5 mM or 15 mM), alone or supplemented with 4 mM glutamine and 10 mM leucine. Media aliquots were taken and placed on ice for insulin analysis at 0, 1, and 2 hrs. At the end of the 2 hr isotopic labeling period, the cells were quenched and extracted for 13C-NMR analysis. Relative 13C enrichment and isotopomer distribution of glutamate was determined by 13C-NMR spectroscopy with an AVANCE 500-MHz spectrometer (Bruker Instruments, Inc. Billerica, MA) [6].

Metabolite Analysis

Total protein was measured spectrophotometrically, based on the method of Bradford (Bio-Rad). Insulin was determined by ELISA for rat insulin (100% cross-reactivity to human insulin, ALPCO).

Oxidative Phosphorylation: 31P-NMR Measured Rates of ATP Synthesis and Fluorometric Measured Rates of Oxygen Consumption

ATP synthesis rates of alginate-encapsulated INS-1 cells were determined in real time using a 31P-NMR saturation transfer pulse sequence, as previously described [3, 4]. Briefly, INS-1 cells were perifused with KRB or DMEM (flow=1.0 ml/min, 37 °C) in the bioreactor in the bore of the AVANCE-500 NMR spectrometer. After a pre-equilibration period with 2.5 mM glucose, 31P-NMR spectra and saturation transfer experiments were acquired during step changes in secretagogues, glucose, and glutamine plus leucine. 31P-NMR spectra were continuously collected in 20-min experiments, with 3 to 4 measurements collected for each substrate level.

ATP synthesis rates were calculated from the intracellular Pi concentration and the ATP synthesis rate constant [3, 4]. Basal intracellular Pi (13.0±1.2 nmol/mg-protein) was measured using tandem mass spectrometry. The ATP synthesis rate constant was calculated from the longitudinal relaxation time of intracellular Pi, and the change in the intracellular Pi signal when the terminal phosphate of ATP is saturated compared to a control spectra (i.e., the saturation pulse is symmetrically offset from Pi resonance).

Oxygen consumption rates

Oxygen consumption rates of freshly trypsinized cells or encapsulated cells were measured using a Fiber Optic Oxygen Monitor (Model 210, Instech Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA) [5]. A 250 µl chamber was loaded with ~2×106 cells, or ~5 beads and changes in the oxygen concentration were monitored under buffer conditions and substrate additions identical to 31P-NMR experiments for measurement of ATP synthesis rates.

Viability of entrapped cells as determined by OCR

Freshly trypsinized cells were used for this work and the OCR was measured in three different media: DMEM, RPMI (as used for INS-1 cell culture) and G0-PBS. The fractional viability as measured with the Guava PCA (live/dead staining) was 97 ± 2% n=5 and was not significantly different in any of the three media. In addition viability measurements were conducted before and after the OCR measurement (by removing cells from the OCR chamber) and were not significantly different. OCR in glucose and glutamine-free PBS is 49±7 % (n=4) of that measured in RPMI and DMEM, and are in excellent agreement with measurements we have been making with entrapped INS-1 cells. We also conducted a measurement with pyruvate stimulation (2 mM) in G0-PBS and observed an increase of more than 100%, again in very close agreement with previous measurements in KRB and PBS with entrapped cells. These data suggest that the metabolic responsiveness of freshly trypsinized INS-1 cells is essentially the same as entrapped, overnight-cultured INS-1 cells used for our 31P-NMR studies of ATP synthesis.

Statistical analyses

All data are reported as means ± SEM. Unpaired two-tailed student’s t-tests were used for comparisons between groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Media effects on insulin secretion rates, oxygen consumption rates (OCR), and rates of ATP synthesis

As the original studies demonstrating the discrepancy between of correlation of OCR and insulin secretion rates in DMEM vs KRB were done in the mouse βHC9 cell line [2], we first needed to establish whether the observed media effects would hold true for β-cell lines from other rodent species. Over the past decade, the rat insulinoma cell line, INS-1 832/13 has become established as a valuable research tool to define the mechanisms of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion of human β-cells [8], and was therefore chosen for these studies.

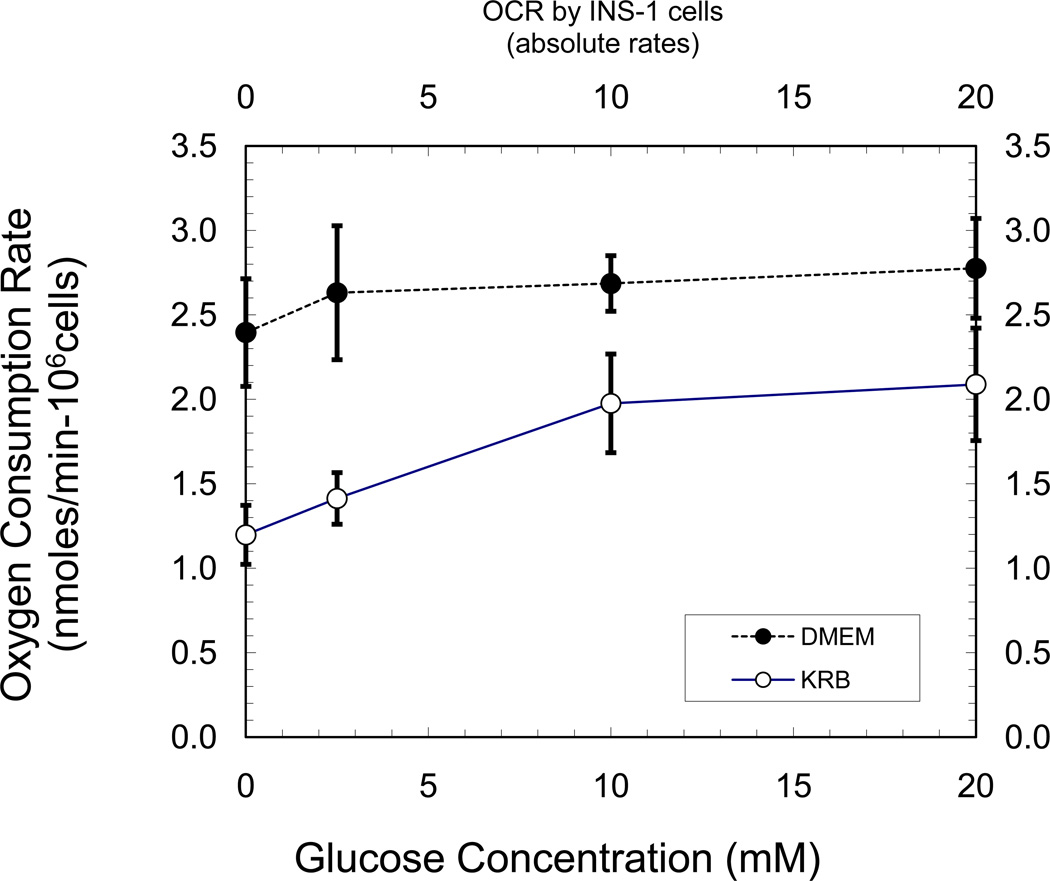

In comparison to KRB, basal and stimulated insulin secretion rates from the INS-1 cells were higher in DMEM (Table 1). Basal ISRs were ~2.6-fold higher in DMEM. And increasing glucose to 15 mM, or the addition of 4 mM glutamine, led to a similar fold-increase in the insulin secretion rate for both KRB and DMEM. The responsiveness of OCR to changing glucose concentrations though, was different in KRB than in DMEM (Figure 1). Under both basal and stimulatory conditions, OCRs were consistently higher in DMEM in comparison to KRB (Figure 1). At 2.5 mM glucose, OCR was ~2-fold higher in DMEM in comparison to KRB. Raising glucose concentration to 10 mM in KRB, resulted in a robust 40% increase in OCR with a further ~10% increment upon increasing glucose to 20 mM. In contrast, in DMEM there was no significant change in OCR upon raising glucose from 2.5 mM to 10 or 20 mM. These results are consistent with those previously reported by Papas and Jarema [2], and prompted us to look more closely at the mechanisms responsible for the apparent discrepancy between the relatively large changes in glucose-stimulated changes in OCR and insulin secretion rates observed in KRB, when compared to a more physiologically relevant DMEM. The anomalies of OCR and ISR, led us to ask whether there were differences in the efficiency of coupling glucose metabolism with rates of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in DMEM compared to KRB. To answer this, we used 31P-NMR saturation-transfer experiments to measure ATP synthesis rates in real time under basal and nutrient-stimulated conditions [3, 4].

Table 1.

Insulin secretion rates in INS-1 832/13 cells relative to KRB (2.5 mM glucose).

| Buffer | 2.5 mM glucose | 2.5 mM glucose + 4 mM gln |

15 mM glucose | 2.5 mM glucose + 4 mM gln |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRB | 1.0±0.1 | 1.7±0.2* | 5.1±0.7* | 7.1±1.0* |

| DMEM | 2.6±0.4* | 4.3±1.4* | 9.9±0.5* | 12.5±1.3* |

Insulin secretion rate of KRB (2.5 mM glucose) = 14.5±0.9 ng/mg-protein/hr. n=2 to 4 measurements per condition. Significance compared to buffer with 2.5 mM glucose

p<0.05

Figure 1.

Oxygen consumption of INS-1 cells in KRB and DMEM. OCRs were measured after a 1 hr pre-equilibration in KRB or DMEM (G2.5, 37° C) prior to transfer to chamber and OCR measurements.

ATP synthesis in DMEM and KRB

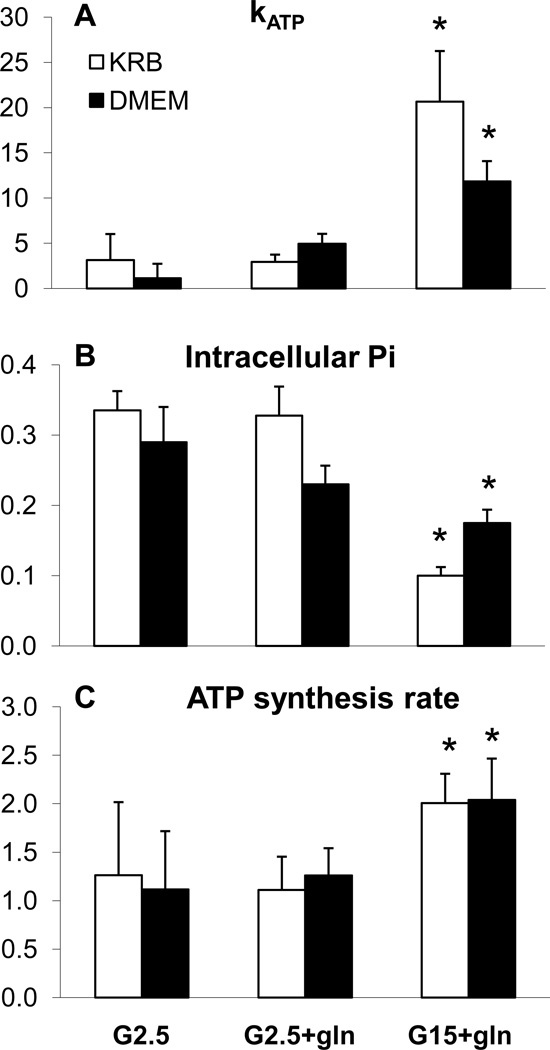

Entrapped INS-1-derived cells were perfused in the bioreactor in the bore of the NMR spectrometer and 20-minute 31P-NMR spectra were acquired to measure intracellular Pi concentration and ATP synthesis rates during step changes in glucose and glutamine. From the saturation transfer experiments, the rate constant, kATP was measured (Figure 2A), and the rate of ATP synthesis (Figure 2C) was then calculated as the product of the kATP and the concentration of intracellular phosphate (Figure 2B). Although, kATP and ATP synthesis rates are proportional, the striking decrease in the intracellular Pi in response to secretagogues blunted the magnitude of changes in ATP synthesis in comparison to the much more dynamic changes in kATP.

Figure 2.

31P-NMR measured rates of ATP synthesis and intracellular Pi of INS-1 cells during perfusion in glutamine-free DMEM with addition of select secretogogues. (A) rate constant (kATP) for unidirectional ATP synthesis in mitochondria. (B) Cytosolic Pi concentration calculated from the 31P-NMR peak intensity of intracellular Pi normalized to the constant extracellular Pi and from LC/MS/MS determined concentration. (C) ATP synthesis rates calculated from the rate constant and Pi concentration. Data are mean + S.E. of four to six NMR-perifusion experiments for each condition, with significance determined by student’s t-test. *P<0.05, compared to basal).

In contrast to the elevated oxygen consumption rates in DMEM compared to that in KRB, we found that ATP synthesis rates were identical under all conditions in both KRB and in DMEM. The addition of glutamine, or raising glucose to 15 mM led to an identical increase in the ATP synthesis rate in both media. The rates of ATP synthesis led to similar levels of ATP at both low and high glucose in both media (G2.5: KRB=10.3±0.7 and DMEM=14.5±2.0, G15: KRB=10.3±0.7 and DMEM=13.8±0.7; KRB data from reference 6). The rates of ATP synthesis combined with the OCR results indicate a greater degree of mitochondrial uncoupling in DMEM relative to that in KRB.

The substantially elevated rates of both basal and stimulated insulin secretion in DMEM in comparison to KRB (Table 1), despite the similar of rates of ATP production at both 2.5 to 15 mM (Figure 2) and ATP concentrations (Table 2), implicates coupling mechanisms other than the recognized action of increased ATP to ADP ratio to affect closure of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel [1]. We, and others, have shown that in KRB (and other simple buffers such as PBS), rates of insulin secretion are tightly correlated with the rate of anaplerosis (via PC and GDH) [6, 9]. This observed correlation has led to the hypothesis that insulin secretion is coupled to the export of mitochondrial 2nd messengers, such as malate and citrate, resulting from the high rates of anaplerosis observed in the mitochondria of the β-cell [10, 11]. To test the hypothesis that increased rates of anaplerotic flux could account for the augmented insulin secretion observed in DMEM, we used a 13C-labeling approach to quantify the relative contribution of anaplerotic inputs into the TCA cycle.

Table 2.

ATP concentrations in INS-1 832/13 cells.

| Glucose alone | + 4mM glutamine |

+10 mM leucine |

+ 4mM glutamine + 10 mM leucine |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 mM glucose | 14.5±2.0 | 14.8±1.2 | 15.1±0.8 | 14.5±2.0 |

| 15 mM glucose | 16.0±0.2 | 12.7±2.0 | 14.2±2.1 | 12.4±0.2 |

ATP concentration was pmol/10−3 cells in INS-1 cells after 2 hr preincubation in buffer with 2.5 mM glucose, followed by 2hr incubation in buffer with indicated substrate additions (n=2 to 4). Significance compared to buffer with 2.5 mM glucose (total: 4 hr)

p<0.05

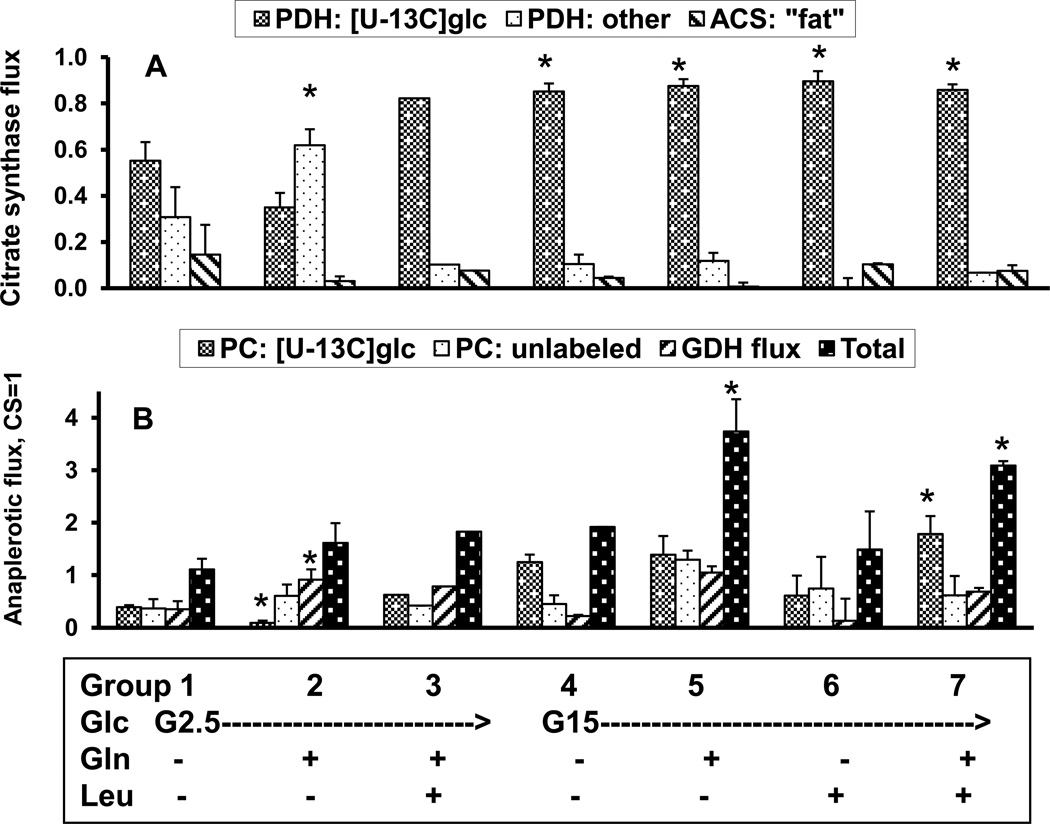

Media effects on the correlation of Insulin Secretion Rates with Anaplerosis

At basal glucose (2.5 mM), only ~one-half of the acetyl-CoA originated from exogenous glucose (Figure 3A) in DMEM. In figure 3A, the fraction of acetyl-CoA originating from exogenous glucose is represented as “PDH: [U-13C]glc”. Anaplerotic flux accounted for 52±10% of carbon entry into the Kreb’s cycle flux (Figure 3B), with approximately equivalent contributions from each of the anaplerotic pathways (i.e., PC from glucose: “PC: [U-13C]glc”, PC from unlabeled substrate: “PC: unlabeled”, and GDH from glutamate). This flux distribution is essentially the same as what we previously observed in KRB [6].

Figure 3.

Relative flux rates in INS-1 cells determined after 2 hour pre-incubation in glutamine-free DMEM buffer containing 2 mM glucose, followed by 2 hrs incubation at 37 °C in KRB buffer containing [U-13C6]glucose (2.5 mM or 15 mM) alone, or with either 4 mM glutamine, 10 mM leucine, or both glutamine and leucine. Flux rates are expressed relative to citrate synthase (CS) flux of unity, as determined by analysis of the 13C isotopic isomers of glutamate using the modeling program, “tcacalc”. Panel A presents relative fluxes of PDH with [U-13C6]glucose, PDH with unlabeled substrate, and acetyl CoA synthase. Panel B presents relative fluxes of PC from [U-13C6]glucose, PC with unlabeled substrate, and GDH with glutamine. Statistical significance determined by student’s t-test. *P< 0.05, compared to basal.

With the increase of glucose to 15 mM, ~85% of the acetyl-CoA supplying the TCA cycle came from exogenous glucose (Figure 3B). In contrast to the 3-fold increase in anaplerotic flux with the addition of 4 mM glutamine to basal KRB [6], the addition of 4 mM glutamine to glutamine-free DMEM had negligible effect on the total anaplerotic flux (sum of PC: [U-13C]glc, PC: unlabled, GDH flux = 62±15%). In KRB, we found that the majority of the increased anaplerosis was attributed to increased GDH flux [6]. In DMEM though, a slight reduction in PC flux was balanced by an increase in GDH flux to maintain a constant anaplerotic flux. Increasing glucose concentration to 15 mM in glutamine-free DMEM increased anaplerotic flux ~2-fold, mostly through an increase in PC flux of [U-13C]glucose. Exogenous glutamine, with 15 mM glucose, further enhanced anaplerotic flux, both through GDH and from PC flux, whereas the addition of leucine had no detectable activation of GDH flux. As in KRB [6], in DMEM the addition of leucine, at both low and high glucose, did not result in the expected activation of GDH flux and entry of glutamine into the TCA cycle [12, 13], but rather led to an increase in PC flux.

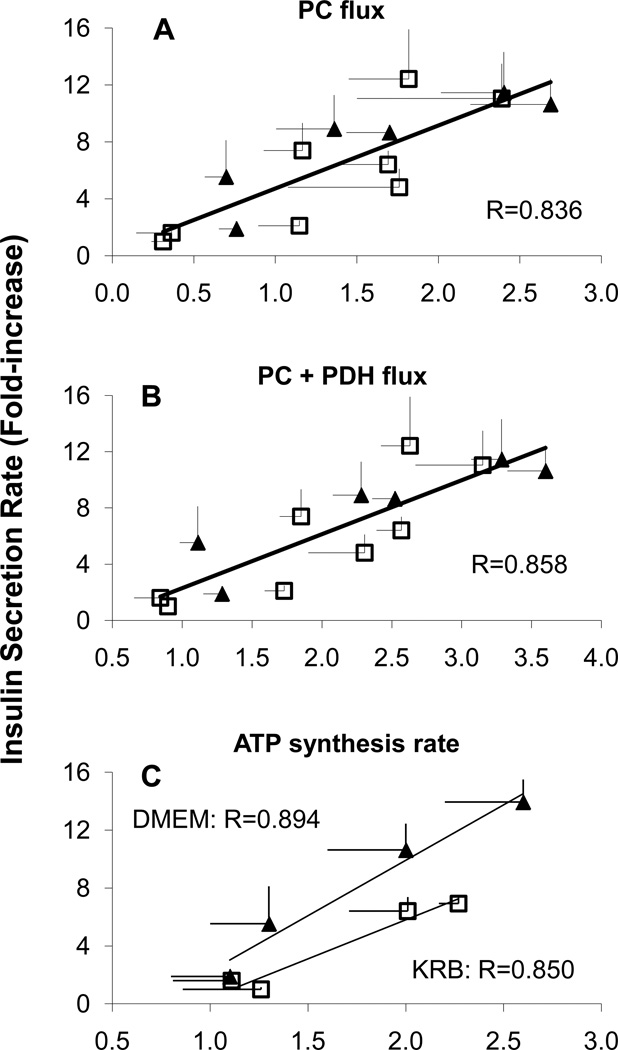

As previously established, insulin secretion rates strongly correlated with anaplerosis via pyruvate carboxylase flux. The correlation with insulin resistance was further strengthened by the sum of the PC anaplerosis and PDH flux of exogenous glucose [6]. Here, we found that these correlations held for flux rates in DMEM as well (ISR vs PC flux, R=0.873, ISR vs PDH+PC flux, R=0.894). In fact, the correlation in KRB was congruent that the correlation in DMEM (Figure 4 A and B). Combining the results reported here for DMEM (solid diamonds) with those found in KRB (open squares, data from [6]), we found a strong correlation of insulin secretion with PC (R2=0.669). In contrast, the correlation of ISR vs ATP synthesis rates in KRB and DMEM fell on two distinct and approximately parallel lines (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

A.) Correlation between insulin secretion rates and total pyruvate carboxylase (PC) flux rates relative to citrate synthase flux of INS-1 cells in KRB (open squares, data from Reference [6]) and DMEM (solid diamonds) buffer containing glucose (2.5 mM or 15 mM) supplemented with either 4 mM glutamine, 10 mM leucine, or both glutamine and leucine over 2 hours at 37 °C. PC flux is the sum of PC flux of [U-13C6]glucose and PC flux of an unlabeled pyruvate pool, as calculated by analysis of the 13C isotopic isomers of glutamate using the modeling program, “tcacalc”. B.) Correlation between insulin secretion rates with the sum of total PC flux and PDH flux from exogenous ({U-13C]glc) rates relative to citrate synthase flux of INS-1 cells in KRB (open squares, data from Reference [6]) and DMEM (solid diamonds) buffer as describe above. C.) Correlation between insulin secretion rates with 31P-NMR determined rates of ATP synthesis in KRB (open squares, data from Reference [6]) and DMEM (solid diamonds) buffer as describe above.

The strong correlation between anaplerosis and rates of insulin secretion in DMEM and KRB, and especially their congruency, supports the hypothesis that the export of mitochondrial 2nd messengers couples responsive changes in mitochondrial metabolism to insulin secretion [6, 9–11]. A strong case has been made that the transfer of mitiochondrial reducing equivalents to cytosolic NADPH, by means of mitochondrial-cytosolic substrate cycling via pyruvate [10, 11, 14–17] could serve the role as a 2nd messenger. Intriguingly, the studies of Kibbey et al. [18, 19] on the phospho-enol-pyruvate cycle point towards a coupling and/or potentiating factor other than NADPH. But as yet, neither the identity of a distinct mitochondria-derived 2nd messenger, nor a definitive biochemical mechanisms linking cycling with insulin secretion has been established. The results presented here, and previously [6], suggest that signaling mechanisms tied to the rates of anaplerosis and the TCA cycle augment the signaling provided by ATP production, and are responsible for the enhanced rates of insulin secretion in more complex and physiologically-relevant media.

Highlights.

-

>

We studied media effects on mechanisms of insulin secretion of INS-1 cells.

-

>

Insulin secretion was higher in DMEM than KRB despite identical ATP synthesis rates.

-

>

Insulin secretion rates correlated with rates of anaplerosis and TCA cycle.

-

>

Mitochondria metabolism and substrate cycles augment secretion signal of ATP.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the United States Public Health Service (R01 DK071071, DK40936, P30 DK45735, and U24 DK59635)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Matschinsky FM. Banting Lecture 1995. A lesson in metabolic regulation inspired by the glucokinase glucose sensor paradigm. Diabetes. 1996;45:223–241. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papas KK, Jarema MAC. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion is not obligatorily linked to an increase in O2 consumption in βHC9 cells. Am J. Physiol. 1998;275:E1100–E1106. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.6.E1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pongratz RL, Kibbey RG, Kirkpatrick CL, Zhao X, Wollheim CB, Shulman GI, Cline GW. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to impaired insulin secretion in INS-1 cells with dominant-negative mutations of HNF-1alpha and in HNF-1alpha-deficient islets. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:16808–16821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807723200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiederkehr A, Park K-S, Dupont O, Demaurex N, Pozzan T, Cline GW, Wollheim CB. Mitochondrial matrix alkalinisation is an activation signal in islet β-cell metabolism-secretion coupling. EMBO J. 2009;28:417–428. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papas KK, Pisania A, Wu H, Weir GC, Colton CK. A stirred microchamber for oxygen consumption rate measurements with pancreatic islets. Biotech Bioeng. 2007;98:1071–1082. doi: 10.1002/bit.21486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cline GW, LePine R, Papas KK, Shulman GI. Simultaneous anaplerotic pathways enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in INS-1 cells as determined by 13C-NMR isotopomer analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:44370–44375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FMH. Analysis of tricarboxylic acid cycle of the heart using 13C isotope isomers. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259:H987–H995. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H987. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB. Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2000;49:424–430. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuit F, De Vos A, Farfari S, Moens K, Pipeleers D, Brun T, Prentki M. Metabolic fate of glucose in purified islet cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:18572–18579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu D, Mulder H, Zhao P, Burgess SC, Jensen MV, Kamzplova S, Newgard C, Sherry AD. 13C NMR isotopomer analysis reveals a connection between pyruvate cycling and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, USA. 2002;99:2708–2713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052005699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDonald MJ, Fahien LA, Brown LJ, Hasan NM, Buss JD, Kendrick MA. Perspective: emerging evidence for signaling roles of mitochondrial anaplerotic products in insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E1–E15. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00218.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sener A, Malaisse WJ. L-leucine and a nonmetabolized analogue activate pancreatic islet glutamate dehydrogenase. Nature. 1980;288:187–189. doi: 10.1038/288187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sener A, Malaisse-Lagea F, Malaisse WJ. Stimulation of pancreatic islet metabolism and insulin release by a nonmetabolizable amino acid. Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:5460–5464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pongratz RL, Kibbey RG, Shulman GI, Cline GW. Cytosolic and mitochondrial malic enzyme isoforms differentially control insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:200–207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602954200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivarsson R, Quintens R, Dejonghe S, Tsukamoto K, in ’t Veld P, Renstrom E, Schuit FC. Redox control of exocytosis regulatory role of NADPH, thioredoxin, and glutaredoxin. Diabetes. 2005;54:2132–2142. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ronnebaum SM, Ilkayeva O, Burgess SC, Joseph JW, Lu D, Stevens RD, Becker TC, Sherry AD, Newgard CB, Jensen MV. A pyruvate cycling pathway involving cytosolic NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:30593–30602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joseph JW, Jensen MV, Ilkayeva O, Palmieri F, Ala´rcon C, Rhodes CJ, Newgard CB. The mitochondrial citrate/isocitrate carrier plays a regulatory role in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:35624–35632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kibbey RG, Pongratz RL, Romanelli AJ, Cline GW, Shulman GI. Mitochondrial GTP regulates glucose-induced insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 2007;5:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stark R, Turcu A, Pasquel F, Pongratz RL, Cline GW, Shulman GI, Kibbey RG. Mitochondrial PEPCK links anaplerosis and mitochondrial GTP with insulin secretion. J. Biol Chem. 2009;284:26578–26590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.011775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]