Abstract

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a serine/threonine protein kinase, acts as a “master switch” for cellular anabolic and catabolic processes, regulating the rate of cell growth and proliferation. Dysregulation of the mTOR signaling pathway occurs frequently in a variety of human tumors, and thus, mTOR has emerged as an important target for the design of anticancer agents. mTOR is found in two distinct multiprotein complexes within cells, mTORC1 and mTORC2. These two complexes consist of unique mTOR-interacting proteins and are regulated by different mechanisms. Enormous advances have been made in the development of drugs known as mTOR inhibitors. Rapamycin, the first defined inhibitor of mTOR, showed effectiveness as an anticancer agent in various preclinical models. Rapamycin analogues (rapalogs) with better pharmacologic properties have been developed. However, the clinical success of rapalogs has been limited to a few types of cancer. The discovery that mTORC2 directly phosphorylates Akt, an important survival kinase, adds new insight into the role of mTORC2 in cancer. This novel finding prompted efforts to develop the second generation of mTOR inhibitors that are able to target both mTORC1 and mTORC2. Here, we review the recent advances in the mTOR field and focus specifically on the current development of the second generation of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents.

Keywords: mTOR, inhibitor, rapamycin, rapalogs, cancer

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a 289 kDa atypical serine/threonine (S/T) protein kinase, is considered a member of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-related kinase (PIKK) superfamily because its C-terminus shares a strong homology with the catalytic domain of PI3K[1]. Cumulative evidence demonstrates that mTOR plays a central role in the synthesis of key cellular proteins that are important for several aspects of cell growth and proliferation[2]–[4] Dysregulation of mTOR and other proteins in its signaling pathway often occurs in a variety of human tumors, and these tumor cells have shown higher susceptibility to inhibitors of mTOR than normal cells[5]–[9]. Thus, mTOR has emerged as an important target for the development of anticancer agents. mTOR is found in two distinct multiprotein complexes within the cells, mTORC1 and mTORC2, which are evolutionarily conserved from yeast to mammals[10],[11]. These two complexes consist of unique mTOR-interacting proteins that determine their substrate specificity. mTORC1 phosphorylates p70 S6 kinase (S6K) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (elF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and regulates cell growth, proliferation, survival, and motility by integrating growth factors, nutrients, stressors, and energy signals[12],[13]. mTORC2 phosphorylates Akt (protein kinase B, PKB), serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1), protein kinase Cα (PKCα), and the focal adhesion proteins, and it controls the activities of the small GTPases (RhoA, Cdc42 and Rac1) and regulates cell survival and the actin cytoskeleton[14]–[18].

mTORC1

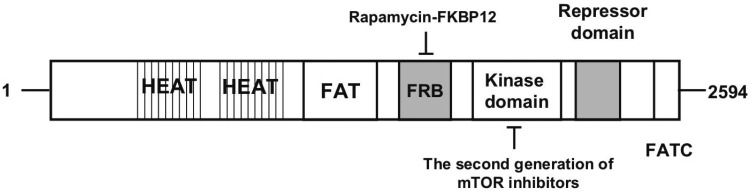

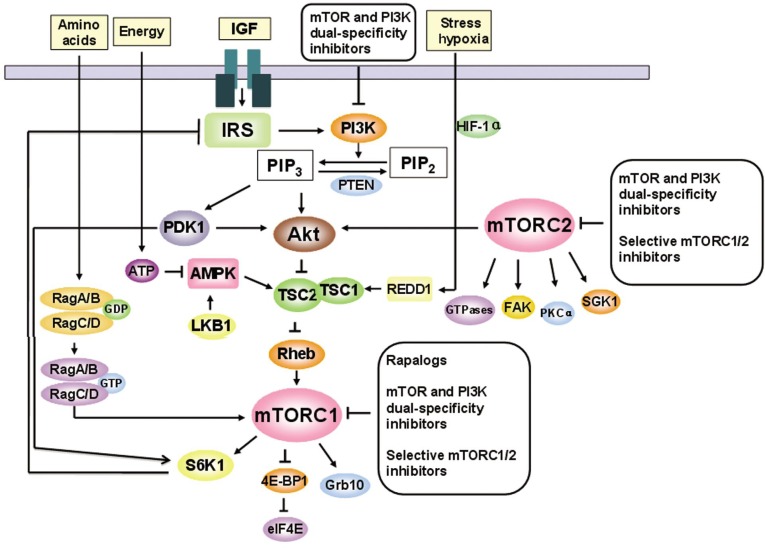

Currently, mTORC1 is known to consist of mTOR, regulatory associated protein of mTOR (raptor), mLST8 (also termed G-protein β-subunit-like protein, GβL, a yeast homolog of LST8), and two negative regulators, proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa (PRAS40) and DEP domain-containing protein 6 (DEPDC6 or DEPTOR)[19]–[21]. mTOR is the core component of mTORC1 and mTORC2[11]–[14]. Structurally, mTOR contains 2549 amino acids. A tandemly repeated HEAT motifs, including Huntingtin, elongation factor 3 (EF3), a subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), and TOR, comprises the first 1200 amino acids[22],[23]. Immediately downstream of the HEAT repeat region lies a FRAP, ATM, and TRRAP (FAT) domain; an FKBP12-rapamycin binding (FRB) domain; a catalytic kinase domain; an auto-inhibitory (repressor domain or RD domain); and a FAT carboxyterminal (FATC) domain, which is located at the C-terminus of the protein (Figure 1)[22],[23]. Rapamycin, the first defined mTOR inhibitor, exerts its action by first binding to the intracellular receptor FKBP12. The FKBP12/rapamycin complex then binds the FRB domain in TOR proteins, thereby exerting its cell growth-inhibitory and cytotoxic effects by inhibiting the functions of TOR signaling to downstream targets such as S6K1 and 4E-BP1[10],[24]–[26]. However, the actual mechanism by which rapamycin inhibits mTOR signaling is still not well understood. Rapamycin-FKBP12 has been proposed to inhibit mTOR function by blocking the interaction of raptor with mTOR and thereby disrupting the coupling of mTORC1 with its substrates[27]. mTORC1 acts to integrate four major regulatory inputs: nutrients, growth factors, energy, and stress (Figure 1)[13],[28],[29]. The best characterized signaling pathway that regulates mTORC1 activity is the growth factor/PI3K/Akt pathway[13]. PI3K/Akt signaling regulates mTORC1 through phosphorylation/inactivation of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) 2 (Figure 2)[30],[31]. TSC is a heterodimer composed of the TSC1 and TSC2 subunits, and the TSC1/2 complex acts as a repressor of mTOR function[30],[32],[33]. TSC2 has GTPase-activating protein (GAP) activity towards the Ras family small GTPase Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb), and TSC1/2 antagonizes the mTOR signaling pathway via stimulation of GTP hydrolysis of Rheb[30],[33]–[37]. The TSC1/2 complex can also be activated by energy depletion through the activation of AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) (Figure 2). Under any stress that depletes cellular ATP, such as oxidative stress, hypoxia, or nutrient deprivation, AMPK is activated and phosphorylates unique sites on TSC2, thereby activating the Rheb-GAP activity of TSC, which catalyzes the conversion of Rheb-GTP to Rheb-GDP and thus inhibits mTORC1 activity[30],[33]–[37]. Activation of mTORC1 results in phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K1, the best studied downstream targets of mTOR[38],[39]. Activated S6K1 regulates protein synthesis through phosphorylation of the 40S ribosomal subunit, which has been suggested to increase the translational efficiency of a class of mRNA transcripts with a 5′-terminal oligopolypirymidine[40],[41]. Recently, the mechanism by which S6K1 regulates translation has been further proposed to be via phosphorylation of elF4B at Ser422[42], which causes elF4B to associate with elF3 and promotes elF4F complex formation[43],[44]. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 by mTOR also stimulates protein synthesis through the release of elF4E from 4E-BP1, allowing elF4E to associate with elF4G and other relevant factors to promote cap-dependent translation[45],[46]. Most recently, the growth factor receptor-bound protein 10 (GRB10) was identified as an mTORC1 substrate[47],[48]. Both Hsu et al. [47] and Yu et al. [48] showed that mTORC1 directly phosphorylates and simultaneously stabilizes GRB10, leading to feedback inhibition of the PI3K pathway. Identification of the mTORC1-GRB10 interaction complements a known negative feedback loop in which mTORC1 activation can inhibit the PI3K pathway by S6K1-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), and it fills an important gap in our understanding the underlying mechanisms by which mTORC1 inhibits PI3K-Akt signaling[49],[50].

Figure 1. Schematic structure of mTOR.

The N-terminus of mTOR contains two tandemly repeated HEAT motifs. Downstream of the HEAT repeat region lies a FAT domain, an FRB domain, a catalytic kinase domain, an auto-inhibitory repressor domain, and a C-terminal FATC domain. The first generation of mTOR inhibitors (rapalogs) bind to FRB domain, whereas the second generation of mTOR inhibitors target the kinase domain.

Figure 2. A model of mTOR signaling network.

mTOR signaling regulates multiple cellular processes by sensing nutrients, growth factors, energy, and stress. Arrows represent activation, whereas bars represent inhibition.

The first generation of mTOR inhibitors includes rapamycin and its analogues (also known as rapalogs) that specifically inhibit mTORC1 (Table 1). Rapamycin was originally isolated from a bacteria in the soil on Easter Island (Rapa Nui) in 1975 and was used as a fungicide[51],[52], and it was later used as an immunosuppressant[53]. Subsequent studies showed that rapamycin is also able to act as a cytostatic agent, slowing or arresting the growth of various cancer cell lines. In addition, rapamycin alone can induce apoptosis in several cancer cell lines and sensitize cells to apoptosis induced by other chemotherapeutic agents[54]–[56]. Extensive studies have revealed rapamycin's mechanism of action: upon entering the cells, rapamycin binds the intracellular receptor FKBP12, forming an inhibitory complex that binds the FRB domain in the C-terminus of TOR proteins, thereby exerting a cell growth-inhibitory and cytotoxic effect by inhibiting the functions of TOR signaling to downstream targets[10],[24]–[26]. Rapamycin has very poor water solubility and chemical stability, severely limiting its bioavailability[2]. Thus, several rapalogs with improved pharmacokinetic properties and reduced immunosuppressive effects, including temsirolimus (CCI-779), everolimus (RAD001), and deforolimus (AP23573), have been developed[57],[58]. The minor chemical modifications to each of these rapalogs preserve their interactions with both FKBP12 and mTOR, and therefore, they share the same action mechanism as rapamycin[59]. Temsirolimus and everolimus were recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of advanced/metastatic renal cell carcinoma[60],[61]. The preclinical and clinical studies on the anticancer effect of rapalogs have been extensively reviewed[62]–[64]. Despite these promising data, however, the collective studies have shown that the single agent activity of rapalogs is modest in other major solid tumors[65]. The emergence of resistance to rapalogs is clearly a critical problem and may limit their utility[65]. One of the mechanisms by which resistance to mTORC1 inhibitors is developed is related to the presence of mTORC1-dependent negative feedback loops[65]. mTORC1 activation is postulated to cause a negative feedback loop through S6K1, which directly phosphorylates IRS-1 and finally induces its degradation[49]. Therefore, mTOR inhibition will increase IRS-1 protein expression, resulting in Akt activation[49]. O'Reilly et al.[49] observed that rapamycin up-regulated IRS-1 protein levels and induced Akt activation in a panel of cancer cell lines, partially explaining the general ineffectiveness of rapamycin in the clinic. This study also provides a rationale for the development of effective combination therapy with an mTOR inhibitor and PI3K inhibitor or an inhibitor of the growth factor receptor, such as IGF-IR [49]. As expected, the combination of rapalogs with other anticancer agents, including standard chemotherapies, receptor tyrosine kinase targeted therapies, and angiogenesis inhibitors, has shown greater activity than single agent rapalogs treatment, suggesting that rapalogs may be best utilized in combination therapies[64],[66],[67].

Table 1. mTOR inhibitors.

| mTOR inhibitors | Origination | Development status | Potential use for the tumor types | Action mechanism |

| First generation of mTOR inhibitors | ||||

| Rapamycin | Wyeth, USA | FDA approved | (Renal transplantation) | Bind to the intracellular receptor FKBP12, and the rapamycin/FKBP12 complex then binds to the FKBP-rapamycin binding (FRB) domain of mTOR kinase |

| Temsirolimus (CCI-779) | Wyeth, USA | FDA approved | Renal cell carcinoma | |

| Everolimus (RAD001) | Novartis, Switzerland | FDA approved | Advanced kidney cancer and progressive or metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors | |

| Deforolimus (AP23573) | ARIAD, USA | FDA approved | Designated by the FDA as an orphan drug for treatment of soft-tissue and bone sarcomas | |

| Nab-rapamycin (ABI 009) | Abraxis BioScience, USA | Phase I | Breast cancer, colon cancer | |

| Second generation of mTOR inhibitors | ||||

| mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors | ||||

| PI-103 | Merck, Germany | Preclinical | Acute myeloid leukemia, glioblastoma, melaloma | Target the ATP binding sites of mTOR and PI3K |

| NVP-BEZ235 | Novartis, Switzerland | Phase I/II | Breast cancer, multiple myeloma, glioblastoma, sarcoma, pancreatic cancer | |

| WJD008 | Chinese Academy of Sciences, China | Preclinical | Breast cancer, colon cancer, prostate cancer, glioblastoma, lung cancer | |

| XL765 | Exelixis, USA | Phase I/II | Breast cancer, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, gliomas | |

| SF-1126 | Semafore, USA | Phase I | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, haematological cancer | |

| Selective mTORC1/2 inhibitors | ||||

| Torin1 | Gray Laboratory, Harvard, USA | Preclinical | - | Target the active site of mTOR in both mTORC1 and mTORC2 |

| PP242 | University of California, USA | Preclinical | Multiple myeloma, leukemia, breast cancer | |

| PP30 | University of California, USA | Preclinical | - | |

| Ku-0063794 | Kudos, UK | Preclinical | - | |

| WYE-354 | Wyeth, USA | Preclinical | Breast cancer, prostate cancer, glioblastoma, colon cancer, renal cell carcinoma | |

| WAY-600 | Wyeth, USA | Preclinical | Breast cancer, prostate cancer, glioblastoma, colon cancer, renal cell carcinoma | |

| WYE-687 | Wyeth, USA | Preclinical | Breast cancer, prostate cancer, glioblastoma, colon cancer, renal cell carcinoma | |

| INK128 | Intellikine, USA | Phase I | Multiple myeloma, breast cancer, prostate cancer, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, | |

| AZD8055 | AstraZeneca, UK | Phase I | Gliomas, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma | |

| OSI-027 | OSI, USA | Phase I | Lymphoma, colorectal cancer, melanoma, neuroendocrine tumors, endometrial cancer, renal cell carcinoma, cervical cancer | |

mTORC2

mTORC2 consists of mTOR, mLST8, rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (rictor) and mammalian stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) -interacting protein 1 (mSin1)[16],[68],[69]. In addition, protein observed with rictor (protor), DEPTOR, and Hsp70 are other novel components of mTORC2[70]–[72]. Because mTORC2 was discovered only recently, its functions and regulatory mechanisms are less well understood than mTORC1[16]. In 2005, Akt was identified as the direct substrate of mTORC2 [73]. More specifically, mTORC2 was found to be a long sought-after kinase that phosphorylates Akt on Ser473[73]. Most recently, SGK1 was identified as a novel substrate of mTORC2[14],[74],[75]. mTORC2 phosphorylates SGK1 at its hydrophobic motif site and thereby regulates the activity of SGK1[14]. Unlike mTORC1, mTORC2 is insensitive to acute rapamycin treatment[16]. However, prolonged rapamycin incubation disrupts mTORC2 assembly and inhibits mTORC2 function in certain cells[76]. mTORC2 was suggested to be activated by PI3K because growth factors stimulate mTORC2 activity and low concentrations of wortmannin, a specific PI3K inhibitor, inhibits Akt Ser473 phosphorylation[73]. However, the mechanism by which mTORC2 is activated by PI3K is not understood. The main function of mTORC2 is to regulate reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton via the phosphorylation of PKCα and the focal adhesion proteins, and to control the activities of the small GTPases (RhoA, Cdc42, and Rac1)[15]–[18],[77]. The significant finding that mTORC2 directly phosphorylates Akt, an important survival kinase, provides new insight into the role of mTORC2 in cancer[73]. The phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 leads to full Akt activation and may regulate different cellular processes, including cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis, and glucose metabolism[78]. In 2009, Sparks et al.[79] showed that knocking down rictor, an essential component of mTORC2, impairs the ability of PC-3 cells, a human prostate cancer cell line null for PTEN, to form solid tumors in vivo. Importantly, rictor is not required to maintain the integrity of a normal prostate epithelium. These data suggest that mTORC2 is important for the development of prostate cancer caused by PTEN loss but is not important for normal prostate epithelial cells, thus providing rationale for developing mTORC2-specific inhibitors as promising anti-cancer therapeutic agents. Recently, the second generation of mTOR inhibitors, which target the ATP binding site in the mTOR kinase domain and repress both mTORC1 and mTORC2 activity, have emerged, but none of these inhibitors are specific for mTORC2. This class of mTOR inhibitors includes: (1) mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors, which target PI3K in addition to both mTORC1 and mTORC2, and (2) selective mTORC1/2 inhibitors, which target both mTORC1 and mTORC2 (Table 1). The use of the second generation of mTOR inhibitors may overcome some of the limitations of rapalogs[65],[79],[80]. Single agent rapalogs showed limited activity in the majority of tested cancer types[65]. Mechanistically, rapalogs prevented mTORC1-mediated S6K activation, thereby blocking S6K1-mediated negative feedback loop, leading to activation of Akt and promotion of cell survival[49]. Moreover, treatment with rapalogs has been reported to activate the pro-survival extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 pathway through a S6K-PI3K-Ras-mediated feedback loop[81].

mTOR and PI3K Dual-Specificity Inhibitors

Because the catalytic domain of mTOR is homologous to the p110α subunit of PI3K, mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors simultaneously target the ATP binding sites of mTOR and PI3K with similar potency[82]–[86]. By additionally targeting PI3K, these molecules, including PI-103, GNE-477, NVP-BEZ235, BGT226, XL765, SF-1126, and WJD008 (Table 1), may have unique advantages over single-specific mTORC1 and PI3K inhibitors in certain disease settings[82]–[87]. For example, inhibition of mTORC1 activity alone by rapalogs may result in the enhanced activation of the PI3K axis because of the mTOR-S6K1-IRS-1 negative feedback loop[49]. Therefore, the mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors might be sufficient to avoid PI3K pathway reactivation.

PI-103

PI-103, a dual class I PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, is a small synthetic molecule of the pyridofuropyrimidine class[88]. PI-103 potently and selectively inhibited recombinant PI3K isoforms, p110α, p110β, and p110δ, and suppressed mTOR and DNA-PK, which belong to the PIKK family[88]. PI-103 showed inhibitory effects on cell proliferation and invasion in a wide variety of human cancer cells in vitro[88]. In vivo, PI-103 exhibited therapeutic activity against a range of human tumor xenografts, showing inhibitory effects on tumor growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis[88],[89]. In human leukemia cells and primary blast cells from acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) patients, PI-103 suppressed constitutive and growth factor-induced activation of PI3K/Akt and mTORC1[90]. In human leukemia cell lines, PI-103 inhibited cell proliferation and induced cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase. In blast cells, PI-103 induced apoptosis and inhibited the clonogenicity of AML progenitors, indicating the therapeutic value of PI-103 in AML[90]. In addition, PI-103 was able to enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy and sensitize cells to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis[91],[92]. In primary glioblastoma cells derived from patients, PI-103 significantly increased doxorubicin- and etoposide-induced apoptosis, further verifying its clinical relevance[91]. Obviously, these findings may have implications for rational design of drug combination regimens to overcome the frequent chemoresistance of glioblastoma[91].

NVP-BEZ235

NVP-BEZ235 (Novartis), a novel, dual class I PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, is an imidazoquinoline derivative currently in phase I/II clinical trials. NVP-BEZ235 binds the ATP-binding clefts of PI3K and mTOR kinase, thereby inhibiting their activities[83]. Increasing evidence shows that NVP-BEZ235 is able to effectively and specifically reverse the hyperactivation of the PI3K/mTOR pathway, resulting in potent antiproliferative and antitumor activities in a broad range of cancer cell lines and experimental tumors[93]–[95]. In breast cancer cells, NVP-BEZ235 blocked the activation of the downstream effectors of mTORC1/2, including Akt, S6, and 4E-BP1[93]. Meanwhile, NVP-BEZ235 showed greater antiproliferative activity than the allosteric selective mTOR inhibitor everolimus in all cancer cell lines tested[93]. In a xenograft model of BT474-derived breast cancer cells overexpressing either the p110α H1047R oncogenic mutation or the empty vector, NVP-BEZ235 significantly inhibited tumor growth of both xenografts[93]. Consistently, NVP-BEZ235 at nanomolar concentrations suppressed phosphorylation of Akt, S6K, and 4E-BP1 and inhibited cell growth in a panel of cancer cells, including myeloma cells[95],[96] as well as human glioma[97], osteosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma[98]. Recently, a phase I, multicenter, open-label, single-agent, dose-escalation trial of NVP-BEZ235 showed that NVP-BEZ235 is active in patients, especially in those with PI3K pathway dysregulated tumors, and is well tolerated with a favorable safety profile[99]. However, pharmacokinetic studies showed that the area under the curve and Cmax increased non-proportionally with dose and were variable within and among patients, so future studies will use a new formulation of NVP-BEZ235 with improved pharmacokinetic properties. In combining treatments, NVP-BEZ235 together with melphalan, doxorubicin, and bortezomib showed synergistic and additive effects on cell growth inhibition in multiple myeloma cells[95]. In a xenograft model with TC-71 Ewing's sarcoma cell line, treatments with NVP-BEZ235 in combination with vincristine effectively inhibited tumor growth and metastasis[98]. These data suggest potential clinical activity of NVP-BEZ235 combined with chemotherapeutic agents.

WJD008

WJD008, another novel dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, was recently synthesized and exhibited potent inhibition on the kinase activity of both p110α and mTOR[86]. In PIK3CA-mutant transformed cells and a panel of tumor cells, including liver cancer, lung cancer, stomach cancer, glioblastoma, prostate cancer, rhabdomyosarcoma, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, squamous carcinoma, and breast cancer, WJD008 showed potent antiproliferative activity[86].

Selective mTORC1/2 Inhibitors

Recently, several selective mTORC1/2 inhibitors have been developed. These molecules, including Torin1, PP242, PP30, Ku-0063794, WAY-600, WYE-687, WYE-354, INK128, AZD8055, and OSI-027 (Table 1), showed potent, selective inhibition on mTOR. Unlike PI3K family inhibitors, they inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2 without inhibiting other kinases[100]. These molecules were shown to potently inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2 at nanomolar concentrations, as evidenced by inhibition of S6K1 phosphorylation at Thr389 and Akt phosphorylation at Ser473, respectively[100]–[103].

Torin1

Torin1, a pyridinonequinoline compound discovered from a biochemical screen for mTOR inhibitors, was identified as a potent and selective mTOR kinase inhibitor[101]. In vitro kinase assays showed that Torin1 inhibited both mTORC1 and mTORC2 with half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values between 2 nmol/L and 10 nmol/L[101]. In mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), Torin1 potently suppressed the phosphorylation of the downstream substrates of mTORC1 and mTORC2, S6K1 at T389 and Akt at S473, with IC50 between 2 nmol/L and 10 nmol/L as well[101]. Meanwhile, the study showed that Torin1 was at least 200-fold selective for mTOR over other PIKK kinases, including PI3K and the DNA-damage response kinases ATM and DNA-PK, suggesting that Torin1 is a highly selective inhibitor of mTOR[101]. Moreover, Torin1 exhibited a greater inhibitory effect on cell growth and proliferation than rapamycin[101]. Surprisingly, Thoreen et al.[101] argued that these effects of Torin1 are not caused by the inhibition of mTORC2, but by the suppression of rapamycin insensitive functions of mTORC1. These results suggest that mTOR kinase domain inhibitors are useful not only in the study of mTORC2, but also for revealing rapamycin-resistant functions of mTORC1[100],[101].

PP242 and PP30

PP242 and PP30, two novel and specific mTOR kinase domain inhibitors against both mTORC1 and mTORC2, were reported by Feldman et al.[100]. In biochemical assays, these two compounds inhibited mTOR in both mTORC1 and mTORC2 with IC50 values of 8 nmol/L and 80 nmol/L, respectively[100]. Compared with rapamycin, PP242 has a much higher antiproliferative effect in primary MEFs[100]. One might expect that this is due to the inhibition of both mTORC1 and mTORC2. However, the study surprisingly showed that the suppression of mTORC2 by PP242 did not result in a total blockade of Akt, and moreover, the inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation by PP242 was more complete than rapamycin. These results suggest that additional mTORC1 inhibition by PP242 could be the basis for its superior antiproliferation activity[100]. In this regard, further study revealed that the inhibition of translational control and the antiproliferative effects of PP242 require inhibition of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation and elF4E activity[100]. However, a recent study showed that the superior antitumor effect of PP242 over rapamycin in multiple myeloma (MM) cells was not due to a greater inhibition on 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, but to its additional inhibitory effects on mTORC2[104]. Another more recent study showed that knockdown of rictor with prevention of mTORC2 assembly inhibited cell growth and induced apoptosis, further supporting mTORC2 as a therapeutic target in MM[104].

Others

Ku-0063794 (Kudos Pharmaceuticals), WAY-600 (Wyeth), WYE-687 (Wyeth), WYE-354 (Wyeth), INK128 (Intellikine), AZD8055 (Astra Zeneca), and OSI-027 (OSI Pharmaceu ticals) (Table 1), which have been most recently reported as ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors, effectively inhibited both mTORC1 and mTORC2[102],[103],[105]–[107]. Ku-0063794 is a potent and highly selective inhibitor of mTOR with an IC50 of 10 nmol/L[103]. It did not significantly inhibit a panel of 76 protein kinases nor 7 lipid kinases tested[103]. Three pyrazolopyrimidine ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors, WAY-600, WYE-687 and WYE354, potently inhibited recombinant mTOR enzyme with IC50 values of 9, 7, and 5 nmol/L, respectively[102]. Moreover, they were highly selective for mTOR over PI3K families (>100 fold to PI3Kα and >500 fold to PI3Kγ) and did not significantly affect a panel of 24 protein kinases tested[102]. These inhibitors induced G1 cell cycle arrest and exhibited antiproliferative effects against several cancer cell lines[102]. In nude mice bearing PTEN-null PC3MM2 tumors, WYE-354 inhibited both mTORC1 and mTORC2 and suppressed tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner[102]. INK128, which was developed by Intellikine, is another potent and selective mTOR inhibitor[107]. The IC50 for INK128 toward mTOR kinase is at the sub-nanomolar level, and it showed a high selectivity against a panel of more than 400 kinases. In multiple xenograft models, administration of INK128 alone or in combination with other standard targeted therapy or chemotherapy resulted in antiangiogenic and tumor growth inhibitory effects[107]. The preclinical evidence of pharmacologic activity with AZD8055, a first-in-class, orally available, potent, and specific inhibitor of mTOR kinase, has recently been reported[105]. AZD8055 exhibited potent inhibitory activity against mTOR with an IC50 of 0.8 nmol/L and showed at least 1000-fold differential in potency against all class I PI3K isoforms and other members of the PI3K-like kinase family[105]. In the H383 and A549 non-small cell lung cancer cell lines, AZD8055 potently inhibited cell proliferation and induced autophagy[105]. In glioblastoma (U87-MG) and lung cancer (A549) xenografts, a single oral administration of AZD8055 decreased the phosphorylation of S6 at Ser235/236 and Akt at Ser473[105]. AZD8055 also induced significant growth inhibition and/or regression in a broad range of tumor xenografts[105]. Most recently, Jiang et al.[108] reported that a combination of AZD8055 and ocCD40 agonistic antibody induced synergistic antitumor responses in a model of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Currently, AZD8055 is being evaluated in phase I clinical trials. A recent study reported the preclinical characterization of OSI-027, a selective and potent dual inhibitor of mTORC1 and mTORC2 with biochemical IC50 values of 22 nmol/L and 65 nmol/L, respectively[109]. OSI-027 exhibited high selectivity for mTOR relative to PI3Kα, PI3Kβ, PI3Kγ, and DNA-PK (>100-fold)[109]. In several tumor cell lines with activated PI3K-Akt signaling, OSI-027 potently inhibited cell proliferation and induced cell death. OSI-027 was well-tolerated in vivo and demonstrated potent anti-tumor activity in multiple tumor xenografts models. Moreover, OSI-027 showed significantly greater inhibition of tumor growth in GEO and COLO 205 colorectal cancer xenografts compared to rapamycin[109]. Currently, OSI-027 is in phase I clinical trials in cancer patients[106]. Recently, a first-in-human phase I trial exploring three schedules of OSI-027 in patients with advanced solid tumors and lymphoma has been presented[106]. OSI-027 was reported to be well tolerated at the doses and schedules tested. Preliminary evidence of the pharmacological activity of OSI-027 was also observed in this study[106].

Summary

mTOR plays a pivotal role in the control of cell growth and proliferation and is an important anti-cancer drug target. mTOR is found in two distinct multiprotein complexes within the cells, mTORC1 and mTORC2. Rapamycin is widely accepted as selective inhibitor of mTORC1. Rapalogs with improved pharmacokinetic properties and reduced immunosuppressive effects have demonstrated preclinical and clinical therapeutic efficacy in certain types of cancer. However, single agent activity of rapalogs is modest in most tumor types. Mechanistically, the specific inhibition of mTORC1 by rapalogs may induce multiple pro-survival feedback loops, including PI3K-Akt and PI3K-Ras-Erk pathways, leading to the attenuation of the therapeutic effects of the rapalogs. Thus, combination therapy or the use of the second generation of mTOR inhibitors, which include mTOR and PI3K dual-specificity inhibitors and selective mTORC1/2 inhibitors, may overcome some of the limitations of rapalogs and exhibit improved antitumor activity. As expected, the second generation of mTOR inhibitors, which can block PI3K-mediated or mTORC2-mediated Akt activation, have demonstrated improved efficacy, particularly in cancer cells with activating PI3K mutations. Data from early phase of clinical trials have recently shown significant clinical activity and good tolerability for most of these inhibitors. The development of this class of mTOR inhibitors marks the beginning of an exiting new phase in mTOR-based therapeutic strategies. An important requirement to improve the clinical outcomes is the identification of predictive biomarkers that can define the tumor subtypes and patient populations that are most likely to respond to the use of mTOR inhibitors. As these mTOR inhibitors are still in the early stage of evaluation, their therapeutic efficacy and potential toxicity still need to be further investigated. Meanwhile, we are also looking forward to the development of a new generation of mTOR inhibitors that specifically target mTORC2. mTORC2-specific inhibitors might have substantial clinical value in treating cancers by not perturbing the feedback activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway that occurs with mTORC1 inhibition.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from NIH (CA115414 to S.H.) and American Cancer Society (RSG-08-135-01-CNE to S.H.).

References

- 1.Kunz J, Henriquez R, Schneider U, et al. Target of rapamycin in yeast, TOR2, is an essential phosphatidylinositol kinase homolog required for G1 progression. Cell. 1993;73(3):585–596. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90144-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang S, Houghton PJ. Targeting mTOR signaling for cancer therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3(4):371–377. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shamji AF, Nghiem P, Schreiber SL. Integration of growth factor and nutrient signaling: implications for cancer biology. Mol Cell. 2003;12(2):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeliger H, Guba M, Kleespies A, et al. Role of mTOR in solid tumor systems: a therapeutical target against primary tumor growth, metastases, and angiogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(3–4):611–621. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborty S, Mohiyuddin SM, Gopinath KS, et al. Involvement of TSC genes and differential expression of other members of the mTOR signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darb-Esfahani S, Faggad A, Noske A, et al. Phospho-mTOR and phospho-4EBP1 in endometrial adenocarcinoma: association with stage and grade in vivo and link with response to rapamycin treatment in vitro. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135(7):933–941. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0529-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenwald IB. The role of translation in neoplastic transformation from a pathologist's point of view. Oncogene. 2004;23(18):3230–3247. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan JA, Zhang H, Roberts PS, et al. Pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis subependymal giant cell astrocytomas: biallelic inactivation of TSC1 or TSC2 leads to mTOR activation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63(12):1236–1242. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riemenschneider MJ, Betensky RA, Pasedag SM, et al. AKT activation in human glioblastomas enhances proliferation via TSC2 and S6 kinase signaling. Cancer Res. 2006;66(11):5618–5623. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helliwell SB, Wagner P, Kunz J, et al. TOR1 and TOR2 are structurally and functionally similar but not identical phosphatidylinositol kinase homologues in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5(1):105–118. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, et al. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2002;10(3):457–468. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu L, Li F, Cardelli JA, et al. Rapamycin inhibits cell motility by suppression of mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 pathways. Oncogene. 2006;25(53):7029–7040. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fingar DC, Blenis J. Target of rapamycin (TOR): an integrator of nutrient and growth factor signals and coordinator of cell growth and cell cycle progression. Oncogene. 2004;23(18):3151–3171. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Martinez JM, Alessi DR. mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) controls hydrophobic motif phosphorylation and activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1) Biochem J. 2008;416(3):375–385. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu L, Luo Y, Chen L, et al. Rapamycin inhibits cytoskeleton reorganization and cell motility by suppressing RhoA expression and activity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(49):38362–38373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.141168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, et al. Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(11):1122–1128. doi: 10.1038/ncb1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barilli A, Visigalli R, Sala R, et al. In human endothelial cells rapamycin causes mTORC2 inhibition and impairs cell viability and function. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78(3):563–571. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez-Negrete I, Carretero-Ortega J, Rosenfeldt H, et al. P-Rex1 links mammalian target of rapamycin signaling to Rac activation and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(32):23708–23715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, et al. Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell. 2002;110(2):177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00833-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, et al. GbetaL, a positive regulator of the rapamycin-sensitive pathway required for the nutrient-sensitive interaction between raptor and mTOR. Mol Cell. 2003;11(4):895–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sancak Y, Thoreen CC, Peterson TR, et al. PRAS40 is an insulin-regulated inhibitor of the mTORC1 protein kinase. Mol Cell. 2007;25(6):903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(1):21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou H, Huang S. The complexes of mammalian target of rapamycin. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2010;11(6):409–424. doi: 10.2174/138920310791824093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Zheng XF, Brown EJ, et al. Identification of an 11-kDa FKBP12-rapamycin-binding domain within the 289-kDa FKBP12-rapamycin–associated protein and characterization of a critical serine residue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(11):4947–4951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunz J, Hall MN. Cyclosporin A, FK506 and rapamycin: more than just immunosuppression. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18(9):334–338. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90069-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi J, Chen J, Schreiber SL, et al. Structure of the FKBP12- rapamycin complex interacting with the binding domain of human FRAP. Science. 1996;273(5272):239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oshiro N, Yoshino K, Hidayat S, et al. Dissociation of raptor from mTOR is a mechanism of rapamycin-induced inhibition of mTOR function. Genes Cells. 2004;9(4):359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edinger AL, Thompson CB. Akt maintains cell size and survival by increasing mTOR-dependent nutrient uptake. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(7):2276–2288. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider A, Younis RH, Gutkind JS. Hypoxia-induced energy stress inhibits the mTOR pathway by activating an AMPK/REDD1 signaling axis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2008;10(11):1295–1302. doi: 10.1593/neo.08586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, et al. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(9):648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(9):658–665. doi: 10.1038/ncb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao X, Zhang Y, Arrazola P, et al. Tsc tumour suppressor proteins antagonize amino-acid-TOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(9):699–704. doi: 10.1038/ncb847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tee AR, Fingar DC, Manning BD, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)–mediated downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(21):13571–13576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202476899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garami A, Zwartkruis FJ, Nobukuni T, et al. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol Cell. 2003;11(6):1457–1466. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manning BD, Cantley LC. Rheb fills a GAP between TSC and TOR. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28(11):573–576. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Gao X, Saucedo LJ, et al. Rheb is a direct target of the tuberous sclerosis tumour suppressor proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5(6):578–581. doi: 10.1038/ncb999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stocker H, Radimerski T, Schindelholz B, et al. Rheb is an essential regulator of S6K in controlling cell growth in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5(6):559–565. doi: 10.1038/ncb995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price DJ, Grove JR, Calvo V, et al. Rapamycin-induced inhibition of the 70-kilodalton S6 protein kinase. Science. 1992;257(5072):973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1380182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunn GJ, Hudson CC, Sekulic A, et al. Phosphorylation of the translational repressor PHAS-I by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Science. 1997;277(5322):99–101. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jefferies HB, Reinhard C, Kozma SC, et al. Rapamycin selectively represses translation of the “polypyrimidine tract” mRNA family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(10):4441–4445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terada N, Patel HR, Takase K, et al. Rapamycin selectively inhibits translation of mRNAs encoding elongation factors and ribosomal proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(24):11477–11481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raught B, Peiretti F, Gingras AC, et al. Phosphorylation of eucaryotic translation initiation factor 4B Ser422 is modulated by S6 kinases. EMBO J. 2004;23(8):1761–1769. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shahbazian D, Roux PP, Mieulet V, et al. The mTOR/PI3K and MAPK pathways converge on elF4B to control its phosphorylation and activity. EMBO J. 2006;25(12):2781–2791. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, et al. mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell. 2005;123(4):569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marcotrigiano J, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, et al. Cap-dependent translation initiation in eukaryotes is regulated by a molecular mimic of elF4G. Mol Cell. 1999;3(6):707–716. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pause A, Belsham GJ, Gingras AC, et al. Insulin-dependent stimulation of protein synthesis by phosphorylation of a regulator of 5′-cap function. Nature. 1994;371(6500):762–767. doi: 10.1038/371762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsu PP, Kang SA, Rameseder J, et al. The mTOR-regulated phosphoproteome reveals a mechanism of mTORC1-mediated inhibition of growth factor signaling. Science. 2011;332(6035):1317–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.1199498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu Y, Yoon SO, Poulogiannis G, et al. Phosphoproteomic analysis identifies Grb10 as an mTORC1 substrate that negatively regulates insulin signaling. Science. 2011;332(6035):1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.1199484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tzatsos A, Kandror KV. Nutrients suppress phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling via raptor-dependent mTOR-mediated insulin receptor substrate 1 phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(1):63–76. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.63-76.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vezina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975;28(10):721–726. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sehgal SN, Baker H, Vezina C. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. II. Fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975;28(10):727–732. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abraham RT, Wiederrecht GJ. Immunopharmacology of rapamycin. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hosoi H, Dilling MB, Shikata T, et al. Rapamycin causes poorly reversible inhibition of mTOR and induces p53-independent apoptosis in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59(4):886–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shi Y, Frankel A, Radvanyi LG, et al. Rapamycin enhances apoptosis and increases sensitivity to cisplatin in vitro. Cancer Res. 1995;55(9):1982–1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ishizuka T, Sakata N, Johnson GL, et al. Rapamycin potentiates dexamethasone-induced apoptosis and inhibits JNK activity in lymphoblastoid cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;230(2):386–391. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ballou LM, Lin RZ. Rapamycin and mTOR kinase inhibitors. J Chem Biol. 2008;1(1–4):27–36. doi: 10.1007/s12154-008-0003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rizzieri DA, Feldman E, Dipersio JF, et al. A phase 2 clinical trial of deforolimus (AP23573, MK-8669), a novel mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(9):2756–2762. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hartford CM, Ratain MJ. Rapamycin: something old, something new, sometimes borrowed and now renewed. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82(4):381–388. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9637):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hess G, Herbrecht R, Romaguera J, et al. Phase III study to evaluate temsirolimus compared with investigator's choice therapy for the treatment of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(23):3822–3829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou H, Luo Y, Huang S. Updates of mTOR inhibitors. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2010;10(7):571–581. doi: 10.2174/187152010793498663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yuan R, Kay A, Berg WJ, et al. Targeting tumorigenesis: development and use of mTOR inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:45. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-2-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meric-Bernstam F, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. Targeting the mTOR signaling network for cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(13):2278–2287. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carew JS, Kelly KR, Nawrocki ST. Mechanisms of mTOR inhibitor resistance in cancer therapy. Target Oncol. 2011;6(1):17–27. doi: 10.1007/s11523-011-0167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mondesire WH, Jian W, Zhang H, et al. Targeting mammalian target of rapamycin synergistically enhances chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(20):7031–7042. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sadler TM, Gavriil M, Annable T, et al. Combination therapy for treating breast cancer using antiestrogen, ERA-923, and the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, temsirolimus. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13(3):863–873. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, et al. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14(14):1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frias MA, Thoreen CC, Jaffe JD, et al. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr Biol. 2006;16(18):1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pearce LR, Huang X, Boudeau J, et al. Identification of Protor as a novel Rictor-binding component of mTOR complex-2. Biochem J. 2007;405(3):513–522. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Woo SY, Kim DH, Jun CB, et al. PRR5, a novel component of mTOR complex 2, regulates platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta expression and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(35):25604–25612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin J, Masri J, Bernath A, et al. Hsp70 associates with Rictor and is required for mTORC2 formation and activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372(4):578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, et al. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307(5712):1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jones KT, Greer ER, Pearce D, et al. Rictor/TORC2 regulates Caenorhabditis elegans fat storage, body size, and development through sgk-1. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(3):e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Soukas AA, Kane EA, Carr CE, et al. Rictor/TORC2 regulates fat metabolism, feeding, growth, and life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2009;23(4):496–511. doi: 10.1101/gad.1775409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, et al. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22(2):159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu L, Chen L, Chung J, et al. Rapamycin inhibits F-actin reorganization and phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins. Oncogene. 2008;27(37):4998–5010. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129(7):1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sparks CA, Guertin DA. Targeting mTOR: prospects for mTOR complex 2 inhibitors in cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2011;29(26):3733–3744. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vilar E, Perez-Garcia J, Tabernero J. Pushing the envelope in the mTOR pathway: the second generation of inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(3):395–403. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carracedo A, Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al. Inhibition of mTORC1 leads to MAPK pathway activation through a PI3K- dependent feedback loop in human cancer. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(9):3065–3074. doi: 10.1172/JCI34739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heffron TP, Berry M, Castanedo G, et al. Identification of GNE- 477, a potent and efficacious dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20(8):2408–2411. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maira SM, Stauffer F, Brueggen J, et al. Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(7):1851–1863. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zou ZQ, Zhang XH, Wang F, et al. A novel dual PI3Kalpha/ mTOR inhibitor PI-103 with high antitumor activity in non–small cell lung cancer cells. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24(1):97–101. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Molckovsky A, Siu LL. First-in-class, first-in-human phase I results of targeted agents: highlights of the 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology Meeting. J Hematol Oncol. 2008;1:20. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li T, Wang J, Wang X, et al. WJD008, a dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, prevents PI3K signaling and inhibits the proliferation of transformed cells with oncogenic PI3K mutant. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334(3):830–838. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.167940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sanchez CG, Ma CX, Crowder RJ, et al. Preclinical modeling of combined phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase inhibition with endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(2):R21. doi: 10.1186/bcr2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Raynaud FI, Eccles S, Clarke PA, et al. Pharmacologic characterization of a potent inhibitor of class I phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases. Cancer Res. 2007;67(12):5840–5850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fan QW, Knight ZA, Goldenberg DD, et al. A dual PI3 kinase/ mTOR inhibitor reveals emergent efficacy in glioma. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(5):341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Park S, Chapuis N, Bardet V, et al. PI-103, a dual inhibitor of Class IA phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase and mTOR, has antileukemic activity in AML. Leukemia. 2008;22(9):1698–1706. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Westhoff MA, Kandenwein JA, Karl S, et al. The pyridinylfuranopyrimidine inhibitor, PI-103, chemosensitizes glioblastoma cells for apoptosis by inhibiting DNA repair. Oncogene. 2009;28(40):3586–3596. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Prevo R, Deutsch E, Sampson O, et al. Class I PI3 kinase inhibition by the pyridinylfuranopyrimidine inhibitor PI-103 enhances tumor radiosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2008;68(14):5915–5923. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Serra V, Markman B, Scaltriti M, et al. NVP-BEZ235, a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, prevents PI3K signaling and inhibits the growth of cancer cells with activating PI3K mutations. Cancer Res. 2008;68(19):8022–8030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cao P, Maira SM, Garcia-Echeverria C, et al. Activity of a novel, dual PI3-kinase/mTor inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 against primary human pancreatic cancers grown as orthotopic xenografts. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(8):1267–1276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Baumann P, Mandl-Weber S, Oduncu F, et al. The novel orally bioavailable inhibitor of phosphoinositol-3-kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin, NVP-BEZ235, inhibits growth and proliferation in multiple myeloma. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315(3):485–497. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McMillin DW, Ooi M, Delmore J, et al. Antimyeloma activity of the orally bioavailable dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/ mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor NVP-BEZ235. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5835–5842. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu TJ, Koul D, LaFortune T, et al. NVP-BEZ235, a novel dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, elicits multifaceted antitumor activities in human gliomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(8):2204–2210. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Manara MC, Nicoletti G, Zambelli D, et al. NVP-BEZ235 as a new therapeutic option for sarcomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(2):530–540. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Burris H, Rodon J, Sharma RS, et al. ASCO. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2010. First-in-human phase I study of the oral PI3K inhibitor BEZ235 in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors; p. 3005. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Feldman ME, Apsel B, Uotila A, et al. Active-site inhibitors of mTOR target rapamycin-resistant outputs of mTORC1 and mTORC2. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(2):e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thoreen CC, Kang SA, Chang JW, et al. An ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor reveals rapamycin- resistant functions of mTORC1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(12):8023–8032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900301200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yu K, Toral-Barza L, Shi C, et al. Biochemical, cellular, and in vivo activity of novel ATP-competitive and selective inhibitors of the mammalian target of rapamycin. Cancer Res. 2009;69(15):6232–6240. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Garcia-Martinez JM, Moran J, Clarke RG, et al. Ku-0063794 is a specific inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) Biochem J. 2009;421(1):29–42. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hoang B, Frost P, Shi Y, et al. Targeting TORC2 in multiple myeloma with a new mTOR kinase inhibitor. Blood. 2010;116(22):4560–4568. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-285726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chresta CM, Davies BR, Hickson I, et al. AZD8055 is a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor with in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2010;70(1):288–298. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tan DS, Dumez H, Olmos D, et al. ASCO. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2010. First-in-human phase I study exploring three schedules of OSI-027, a novel small molecule TORC1/TORC2 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors and lymphoma; p. 3006. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jessen K, Wang S, Kessler L, et al. AACR. Boston, MA: American Association for Cancer Research; 2009. INK128 is a potent and selective TORC1/2 inhibitor with broad oral antitumor activity; p. B148. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jiang Q, Weiss JM, Back T, et al. mTOR kinase inhibitor AZD8055 enhances the immunotherapeutic activity of an agonist CD40 antibody in cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2011;71(12):4074–4084. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bhagwat SV, Gokhale PC, Crew AP, et al. Preclinical characterization of OSI-027, a potent and selective inhibitor of mTORC1 and mTORC2: distinct from rapamycin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(8):1394–406. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]