Abstract

Stress has been reported to activate the locus coeruleus (LC)–noradrenergic system. However, the molecular link between chronic stress and noradrenergic neurons remains to be elucidated. In the present study adult Fischer 344 rats were subjected to a regimen of chronic social defeat (CSD) for 4 weeks. Measurements by in situ hybridization and Western blotting showed that CSD significantly increased mRNA and protein levels of the norepinephrine transporter (NET) in the LC region and NET protein levels in the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala. CSD-induced increases in NET expression were abolished by adrenalectomy or treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists, suggesting the involvement of corticosterone and corticosteroid receptors in this upregulation. Furthermore, protein levels of protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), and phosphorylated cAMP-response element binding (pCREB) protein were significantly reduced in the LC and its terminal regions by the CSD paradigm. Similarly, these reduced protein levels caused by CSD were prevented by adrenalectomy. However, effects of corticosteroid receptor antagonists on CSD-induced down-regulation of PKA, PKC, and pCREB proteins were not consistent. While mifeprestone and spironolactone, either alone or in combination, totally abrogate CSD effects on these protein levels of PKA, PKC and pCREB in the LC and those in the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala, their effects on PKA and PKC in the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala were region-dependent. The present findings indicate a correlation between chronic stress and activation of the noradrenergic system. This correlation and CSD-induced alteration in signal transduction molecules may account for their critical effects on the development of symptoms of major depression.

Keywords: Norepinephrine transporter, Depression, Chronic social defeat, Rat brain, Locus coeruleus, corticosteroid receptors

1. Introduction

Over the past several decades, numerous investigations with human subjects have demonstrated a close correlation between stressful life events and the onset of an episode of major depression (Brown, 1998; Brown et al., 1994). Moreover, a large body of animal studies (Cui and Vaillant, 1996; Kessler, 1997; Paykel, 1994; Rosenblum et al., 1994; Tennant et al., 1981) has revealed striking parallels in the neurobiological abnormalities caused by stress and those found in depressive patients. These studies convincingly suggest a causal role of stress in the development of depression, in which prolonged stress-induced hypersecretion of glucocorticoids may form part of the intrinsic mechanism underlying the development of depression (Carrasco and Van de Kar, 2003).

On the other hand, a functional disturbance in the central noradrenergic system has also been implicated in the development of depression (Bunney and Davis, 1965). For instance, drugs that selectively antagonize norepinephrine (NE) transporter (NET) and α2-adrenergic receptors serve as effective antidepressants. Moreover, a more direct measure of brain NE levels by placing catheters in the jugular veins of patients suffering from depression revealed a deficit in brain NE levels in these patients (Lambert et al., 2000). In addition, NE depletion leads to a relapse of depressive symptoms in depressed individuals who responded to antidepressants that inhibit NE reuptake (Berman et al., 1999; Delgado and Moreno, 2000).

Since both chronic stress and dysfunctional noradrenergic systems are involved in the development of depression, their interaction may contribute to the pathophysiology of depression. Animal studies have shown that the brain noradrenergic system is rapidly activated by different stressors (Abercrombie and Jacobs, 1987; Anisman and Sklar, 1979; Korf et al., 1973; Ritter et al., 1998), which results in an increase in NE release from terminal regions of noradrenergic nerves (Pacak et al., 1995; Rosario and Abercrombie, 1999; Smagin et al., 1997), and finally can lead to a reduction of brain NE levels (Glavin et al., 1983; Kvetnansky et al., 1977; Nakagawa et al., 1981; Zigmond and Harvey, 1970). Discovering molecular links underlying this interaction has important implications for elucidating the biological basis of depression and identifying new treatments. The NET may be one of target proteins involved in these interactions for its special role in the noradrenergic system.

The NET is a membrane protein primarily located on presynaptic terminals of noradrenergic nerves. In neuronal tissues, reuptake of NE by the NET is the primary mechanism by which NE transmission is inactivated at the synapse (Barker and Blakely, 1995). NET expression has not been found in the serotonergic and dopaminergic neurons. This unique distribution has led to the recognition that the presence of NET serves to identify noradrenergic neurons. Given that NET’s function is related to the antidepressant effects of certain drugs and NET is one of the key proteins in the regulation of noradrenergic transmission, its expressional changes have been related to the development and symptoms of depression. For example, NET knockout mice display significantly less depressive-like behaviors than wild type controls (Xu et al., 2000), are more aggressive in early phases of stress and demonstrate inhibition of depressive-like behavior in chronic stress models (Haller et al., 2002). These findings suggest that depressive behavior in stressed animals requires functional NET and that abnormal NET expression and function could contribute to depressive symptoms (Haenisch et al., 2009; Haller et al., 2002). Likewise, the involvement of NET in stress has been reported previously (Hwang et al., 1999; Rusnak et al., 2001; Zafar et al., 1997). However, effects of stress on NET expression are inconsistent and stressor-dependent. Furthermore, there are very few reports investigating the possible regulatory mechanisms mediating the effects of stress on NET expression in vivo. Thus, it is crucial to evaluate the effects of chronic stress on the expression of NET in the brain and investigate the possible mechanisms by which their interaction may affect the development of depressive symptoms.

In the present study we used a rat model of chronic social defeat (CSD) to examine the effects of this chronic stressor on the expression of NET in the locus coeruleus (LC) and its projections to such terminal areas as the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala. Furthermore, we investigated the expression of protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), and phosphorylated cAMP-response element binding protein (pCREB) in brain regions of CSD rats to explore the possible involvement of these signal transduction-related proteins in the regulation of NET by chronic stress. Our results reveal that CSD upregulated the expression of NET in the LC and its terminal areas through effects on corticosteroid receptors. Also, PKA, PKC and pCREB proteins may be involved in this regulation. The present findings reveal an interaction between chronic stress and the noradrenergic system, which may account for their putative role in the etiology of affective psychiatric disease.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

Male Fischer 344 rats, weighing 200-250g at the beginning of the experiment, Long-Evans retired male breeder and ovariectomized female rats were purchased from Harlan Laboratories Inc. (Indianapolis, IN, USA). All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of East Tennessee State University, and complied with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Rats were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00 h) with ad-libitum access to food and tap water except as specifically described below. After an acclimation period of 5 days, rats were randomly assigned to experimental groups.

2.2. Chronic social defeat paradigm and drug treatment

This protocol is similar to that reported previously with minor modification (Becker et al., 2008). Each pair of Long-Evans rats (larger retired male breeders and sterile female rats) was placed in individual cages for 7 days to establish their territorial “resident” status before the beginning of experiments. Adult male Fischer 344 rats serve as the experimental “intruder” in antagonistic encounters. The experiment began by exposing an “intruder” rat to the home cage of the “resident” after the female rat had been removed. After being attacked and defeated, as shown by freezing behavior and full submissive posture, usually within 2 minutes, the “intruder” was rescued and placed into a small protective cage within the resident’s cage, which allows unrestricted visual, auditory, and olfactory contacts with the resident but precludes further physical contact. The “intruder” was left in the cage of “resident” for one and a half hour in the protective enclosure, and then returned to its home cage where it was subsequently housed individually for the rest of the experimental period. Similarly, some male Fischer 344 rats (control) are given access to the entire resident home cage in the small protective cage when the residents have been removed. Therefore, these rats are never physically attacked and defeated by the residents. This exposure was repeated four times in the first and fourth weeks, and two times in the second and third weeks. One group of rats were adrenalectomized (ADX) by Harlan Laboratories Inc. before shipping to the animal facility of East Tennessee State University. To control for the loss of adrenal steroids, ADX rats were provided with 25 μg/ml corticosterone in their drinking water immediately after rats arrived at the animal facility and during remaining experimental period. This small replacement dose of corticosterone has been shown to be adequate for prevention of post-adrenalectomy alterations in the central nervous system (Pace et al., 2009). The sham operation for corresponding ADX was performed by opening and closing the abdomen without adrenal removal. There are two types of corticosteroid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems: mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs, or Type I) and glucocorticoid receptor (GRs, or Type II) (Reul and de Kloet, 1985; Spencer et al., 1990). Corticosterone binds these two types of receptors but with a difference in affinity of an order of magnitude (Spencer et al., 1993). In order to examine whether these receptors are involved in the CSD-induced regulation of NET expression, relatively specific MR antagonist spironolactone and GR antagonist mifepristone were utilized in these animals. Therefore, some groups of rats were treated with mifepristone (10 mg/kg, daily, s.c.) or spironolactone (15 mg/kg, daily, s.c.), either alone or in combination. The doses of these antagonists are chosen on the basis of previous reports (Haller et al., 1998; Macunluoglu et al., 2008; Ni et al., 1995; Ratka et al., 1989) and our preliminary experiments. All these compounds were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Rats in the untreated control and CSD alone groups were injected with similar volumes of vehicle in the same manner. Corticosteroid receptors antagonists or vehicle were injected 10 minutes prior to the CSD regimen.

2.3. Sucrose consumption test

All rats were given a free choice between two bottles, one containing a 1% sucrose solution and one containing tap water, 72 hours before starting of CSD regimen to familiarize rats with the test condition. At 08:00 am of the third day, all drinking solutions were removed and at 06:30 pm all rats were again allowed access to two freshly prepared bottles of drinking solution for one hour. Water and sucrose solution consumption was measured by comparing bottle weight before and after the 1 hour window as the consumption amount. The regular water bottle was then provided after the test. This consumption test (deprivation in the morning and two bottles of drinking solution provided in the one hour window between 06:30 pm and 07:30 pm) was carried out weekly on the same day of the week (Thursday) throughout the four week CSD regimen. To prevent possible effects of position preference on consumption, the position of the bottles was alternated each time.

2.4. Rat blood sampling and plasma corticosterone determination

On the 28th day (the last session of CSD), rats were sacrificed by rapid decapitation. Trunk blood from rats was quickly collected into chilled glass tubes, which previously had been rinsed with a solution of 1.5% EDTA in saline and dried. Blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 2500 rpm. Plasma obtained was temporarily stored at -80°C and plasma corticosterone was later measured by a radioimmunoassay using a commercial kit [ImmuChem radioimmunoassay kit, MP Biomedicals, LLC in Orangeburg, NY (formerly ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, CA)]. The assay kit was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the following modification: all reagents were used at half strength and the lowest standard concentration in the kit (25 ng) was serially diluted to yield standards at 12.5, 6.25 and 3.125 ng, respectively. The resulting assay had a sensitivity of 3.125 ng and an IC50 of 65 ng. All samples were run in a single assay with an intra-assay variance of less than 8%.

2.5. In situ hybridization to measure NET mRNA

The in situ hybridization method is the same as described before (Zhu et al., 2002). Briefly, after rats were sacrificed, brains were removed and rapidly frozen in 2-methyl-butane on dry-ice, then stored at -80°C until slicing. Sections (16 μm) around the pons-brain stem LC region were cut on a cryostat, mounted on SuperFrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburg, PA), and stored at -80°C. When hybridization was performed, the slides were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde followed by acetylation with acetic anhydride. Lipids were extracted by washing with increasing concentrations of alcohol (50, 70, 95 and 100% [vols]). The [35S]-labeled cRNA probes (Perkinelmer, MA) were transcribed in vitro from cDNAs for rat NET (0.5 kb) in pGEM-3Zf vectors with T7 RNA polymerase. Pre-hybridized sections were incubated with hybridization solution containing the radiolabeled probes at 55°C for 3-5 hours. The brain tissue sections were then washed extensively and apposed to Biomax autoradiographic films (Kodak; Rochester, NY). For higher-resolution studies, sections were also dipped in Kodak NTB2 emulsion (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) and quantitatively analyzed with the Bioquant Nova program (R.M. Biometrics, Inc.; Nashville, TN). The specificity of cRNA probes was tested using three criteria. First, sense probes synthesized from each cDNA were used to perform in situ hybridization in parallel with antisense probes. There were no specific signals on these slides. Second, antisense probes were used on control slides from the cerebellum and cortex and no hybridization signals were detected. Third, antisense probes were hybridized to slides that were treated with RNase A (20 μg/mL) and no hybridization signal was detected. For analysis of in situ hybridization results, 3 sections from each rat and bilateral LC regions from each section were quantitated. A mean value was obtained from these 6 measurements and represented for each rat.

2.6. Detection of protein levels

The LC, hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala of rats were punched from frozen coronal sections, guided by the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). Protein levels of NET along with PKA, PKC and pCREB in these multiple regions were determined by Western blotting. These samples were homogenized in sample buffer containing sodium lauryl sulfate (SDS) and β-mercaptoethanol. After centrifugation at 1000g, protein concentrations of supernatants were measured by using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of samples (10 μg of protein per lane) were loaded on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels for electrophoresis. Protein bands in gels were transferred to polyvinylidene diflouride membranes by electro-blotting. The membranes were incubated with respective primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. These antibodies include a polyclonal antibody against NET from rabbit (1:330 dilution; Alpha Diagnostic Intl. Inc, San Antonio, TX), polyclonal antibodies against PKA or PKC from rabbit (1:250 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), or monoclonal antibodies against pCREB from mouse (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology Inc, Danvers MA, USA). Membranes were then further incubated with secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, 1:3000; Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK). Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham; Piscataway, NJ). Bands were detected by G:Box Imaging (Fyederick, MD, USA), or exposed on films and scanned by Quantity One imaging devices (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Band densities were then quantified by imaging software (Molecular Dynamics IQ solutions, Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA). A linear standard curve was created from optical densities (ODs) of bands with a dilution series of total proteins prepared from brain tissues. OD values of NET, PKA, PKC or pCREB signals were compared and normalized with β-actin immunoreactivities, which were determined on the same blot, to assess equal protein loading. Normalized values were then averaged for all replicated gels and used to calculate the relative changes of the same gel.

2.7. Statistics

All experimental data are presented in the text and graphs as the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA, SigmaStat, Systat Software Inc., Richmond, VA) when multiple treatment groups were compared in all experiments. Then post-hoc Student-Newman-Keuls tests were performed for planned comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Plasma corticosterone measurement and sucrose consumption test

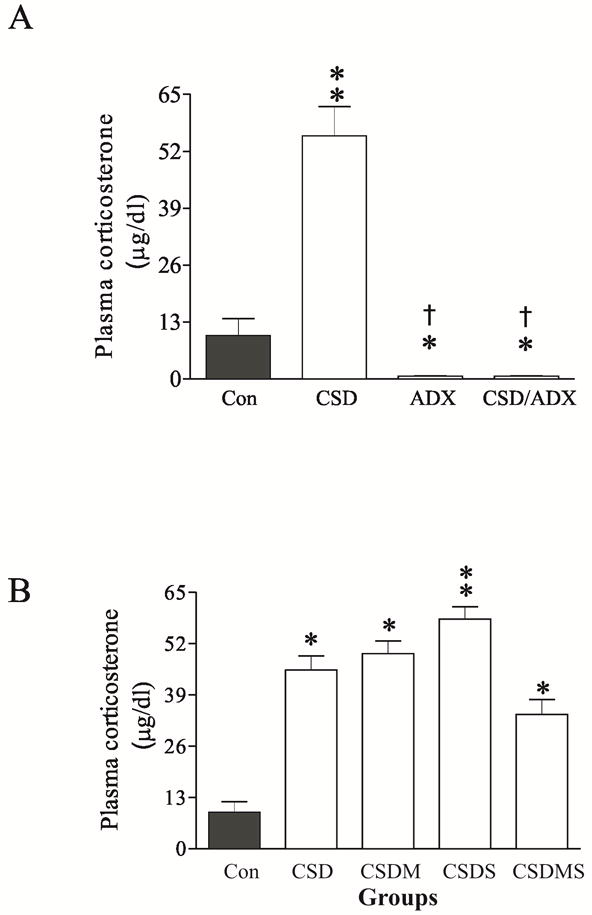

To define the efficacy of chronic stress in inducing hormonal modification, plasma corticosterone levels were measured in samples collected immediately after last CSD paradigm at the end of the four-week stress. CSD significantly affected plasma corticosterone levels (F2,22=15.32, p<0.001 for data of Fig. 1A; F4,36=4.95, p<0.01 for data of Fig. 1B). Post hoc test revealed that plasma corticosterone levels were significantly elevated in the rats subjected to CSD (p<0.01), as compared to control rats. As expected, ADX-alone and CSD/ADX rats showed a relatively lower plasma corticosterone levels (Fig. 1A). Treatment with mifepristone or spironolactone, two antagonists of corticosteroid receptors, alone or in combination, did not significantly influence CSD-caused elevation of plasma corticosterone levels. Compared to those in the CSD rats and CSD-rats injected with mifepristone or spironolactone alone, plasma corticosterone levels in the group co-injected with mifepristone and spironolactone were lower, but this reduction did not reach statistically significant levels (p>0.05; Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Effects of chronic social defeat (CSD) stress, adrenalectomy (ADX), CSD plus adrenalectomy (CSD/ADX) (A, n=8/group), as well as CSD plus treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists (B, n=6/group) on plasma corticosterone concentrations. The trunk blood was collected on the 28th day immediately after the end of last session of CSD. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, compared to the control; † p<0.01, compared to the CSD group. Con: control; CSDM: CSD plus treatment with mifepristone; CSDS: CSD plus treatment with spironolactone; CSDMS: CSD plus treatment with both mifepristone and spironolactone.

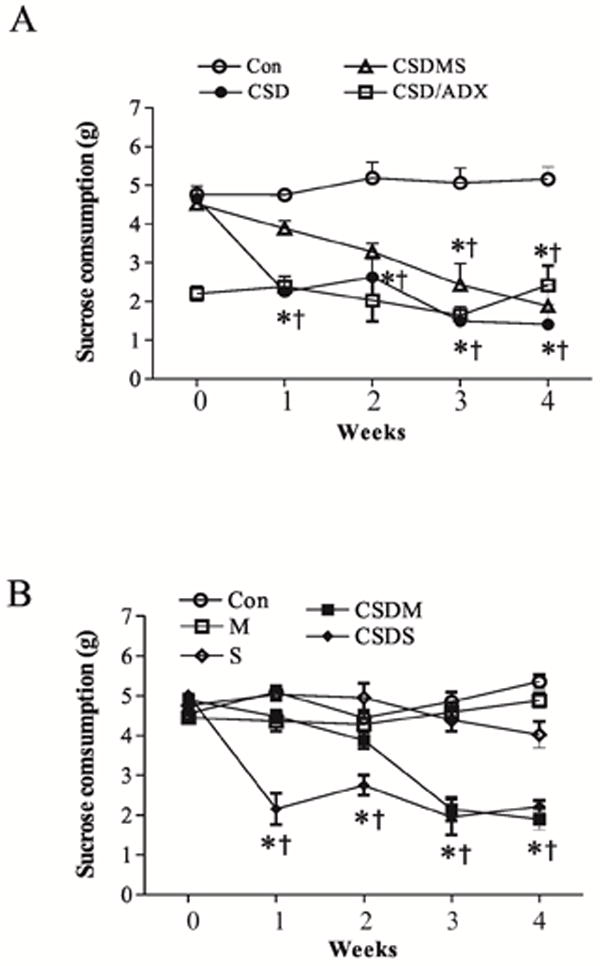

The sucrose consumption test was used to evaluate depressive effects of CSD in rats. As shown in Fig. 2A, the intake of the sucrose solution was not significantly changed in non-stressed animals over the whole duration of the experiment (F4,34 = 2.13, p>0.05). However, it was significantly reduced from the first to fourth week of stress exposure in CSD rats (F4,30 =13.06, p<0.001). When CSD rats were simultaneously treated with both mifepristone and spironolactone, sucrose consumption rate was significantly affected (F4,30=5.51, p<0.01). The sucrose intake in these rats was almost normalized during the first week of the CSD paradigm. However, in the third and fourth week of stress exposure, this apparent normalization disappeared. Instead, sucrose consumption in these corticosteroid receptor antagonist-treated CSD rats markedly decreased (both p<0.05), an effect similar to those in untreated CSD rats. Also, the sucrose consumption of these treated CSD rats at these two time points was significant lower than that of first week (both p<0.05). Interestingly, the base level of sucrose consumption in ADX rats was significantly lower than those of non-stressed animals. This lower level of sucrose consumption was maintained over the remainder of the CSD paradigm, indicating corticosterone secretion after stress may be partly responsible for increased intake of the sweetened solution. Further we separately examined effects of corticosteroid receptor antagonists on sucrose consumption rates. As shown in Fig. 2B, non-CSD rats treated with mifepristone or spironolactone alone did not show any significant alteration in the sucrose consumption, as compared to that of the control. However, treatment with mifepristone, but not with spironolactone, in CSD rats resulted in a similar effect to those of combination of mifepristone and spironolactone. This result may be consistent with the notion that mifepristone possesses stronger antidepressant effect than spironolactone (Belanoff et al., 2001). The water consumption levels were also simultaneously examined in all experimental animals. While most groups across experimental periods showed a stable water intake (data not shown), water consumption levels in ADX rats before CSD were increased by 345.3%, as compared to that in normal rats (4.07±0.13g vs. 1.18±0.12g). Nevertheless, this increased water consumption level disappeared during CSD paradigm, showing a relatively similar water consumption level to that of normal CSD rats (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Sucrose solution intake in rats exposed to CSD stress (n=10-12/group), as well as treatments with corticosteroid receptor antagonists. CSD paradigm was applied to rats for 4 weeks as described in the text. Control CSD-alone rats were injected with vehicle while CSD rats were treated with corticosteroid receptor antagonists. * p<0.05, compared to the base levels (0); † p<0.05, compared to the corresponding time point in the control group. All values in the CSD/ADX group are significant from the corresponding time point in the control group (p<0.05). M: treated with mifepristone alone; S: treated with spironolactone alone; other abbreviations see Fig. 1 above.

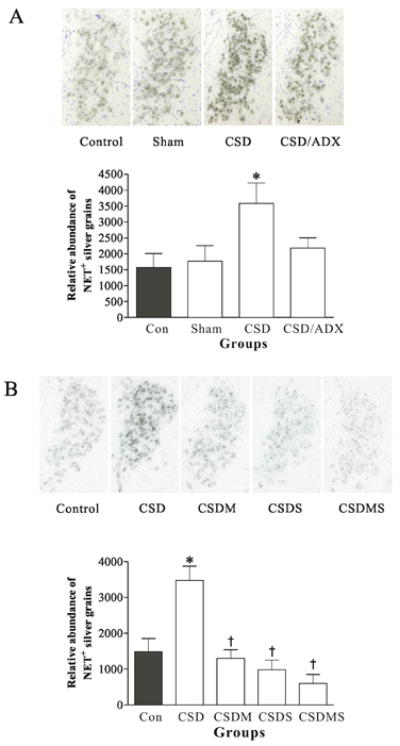

3.2. CSD increased mRNA levels of NET in the LC

To investigate the influence of CSD on the expression of NET in the LC of rats, ex vivo in situ hybridization was performed to measure mRNA levels of NET in rats among the different treatment groups. As shown in Fig. 3A, CSD significantly increased NET mRNA levels (F3,23=3.36, P<0.05). Post hoc tests revealed that there was no significant difference between the control and sham ADX groups, indicating the surgery (sham for ADX) had no effect on NET mRNA levels in the LC. However, CSD significantly increased mRNA levels of NET in the LC region by 129% (P<0.01) compared to those in the control. This CSD-induced elevation in NET mRNA levels was abolished by ADX, indicating the involvement of corticosterone in this regulation.

Figure 3.

Effects of CSD and adrenalectomy (A), as well as treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists (B) on NET mRNA in the LC. Upper panel: NET mRNA in LC tissues of rats detected by in situ hybridization (n=7/group). Coronal brain sections were taken at 9.7 mm posterior from bregma (corresponding to Plate 58 in the brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). Lower panel: Quantitative analyses of mRNA in slides. * p<0.05, compared to the control; † p<0.01, compared to the CSD group. Sham: sham operation. See Fig. 1 for other abbreviations.

To further examine whether the altered NET expression caused by CSD regime was related to corticosteroid receptors, 10 min before exposure to each CSD session rats were pretreated with injection of mifepristone and spironolactone, alone or in combination. Control rats were injected with vehicle. In situ hybridization results showed that treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists markedly influenced the elevation of NET mRNAs by CSD (F3,38=6.35, P<0.001). Treatment with either mifepristone or spironolactone alone, or combination of both completely abolished the CSD-induced increase of NET mRNAs in the LC (Fig. 3B, all p<0.01). Although CSD rats treated with combination of mifepristone and spironolactone exhibited a lower NET mRNA level than those in rats treated with mifepristone or spironolactone alone, as well as that of the control, these differences did not reach the significant level. The results suggest that CSD-induced up-regulation of NET mRNAs was mediated by corticosteroid receptors.

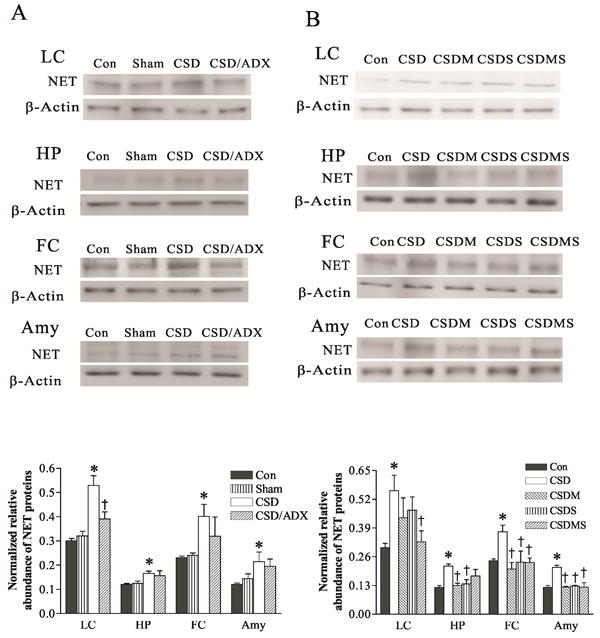

3.3. CSD increased NET protein levels in the LC and its terminal regions

To explore whether CSD alters NET protein levels in the LC and its terminal projection areas, Western blotting was performed in samples from the LC, hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala. As shown in Fig. 4A, there was no significant difference in NET protein levels between the control and ADX sham group in samples from any of these regions, ruling out possible effects of the surgery procedure on NET protein levels. However, CSD markedly increased NET protein levels in these regions (F3,19= 6.45, p<0.01 for LC; F3, 23=4.46, p<0.05 for hippocampus; F3, 19=3.52, p<0.05 for frontal cortex; F3, 19=4.55, p<0.05 for amygdala). The Newman-keuls test revealed that CSD significantly increased NET protein levels in the LC by 76% (p<0.01), in the hippocampus by 38% (p<0.05), in the frontal cortex by 67% (p<0.05), and in the amygdala by 78% (p<0.05), respectively. Similar to the findings of NET mRNA from the LC (Fig. 3), ADX blocked CSD-induced elevation of NET protein levels in all these regions. However, except for in the LC, where NET protein levels in CSD/ADX group was also significantly lower than that of the CSD group (p<0.05), there were no statistical differences between CSD/ADX and CSD groups in the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala. Similarly, the CSD-induced increase of NET protein levels in these four regions was abolished by treatment with mifepristone and spironolactone, either alone or combination (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of CSD and adrenalectomy (A), as well as treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists (B) on NET protein levels in the LC and its terminal regions. The upper figures in A and B show autoradiographs obtained by Western blotting of NET in different regions (n=6-8/group). The lower graph in A and B shows quantitative analysis of band densities. Values of NET bands were normalized to those of β-actin probed on the same blot. *P<0.05, compared to the control group; † p<0.05, compared to the CSD group. HP: hippocampus; FC: frontal cortex; Amy: amygdala; Con: control; Sham: sham operation; CSD/ADX: CSD plus adrenalectomized; CSDM: CSD plus treatment with mifepristone; CSDS: CSD plus treatment with spironolactone; CSDMS: CSD plus treatment with both mifepristone and spironolactone.

3.4. CSD reduced protein levels of PKA, PKC and pCREB in the LC and its terminal regions

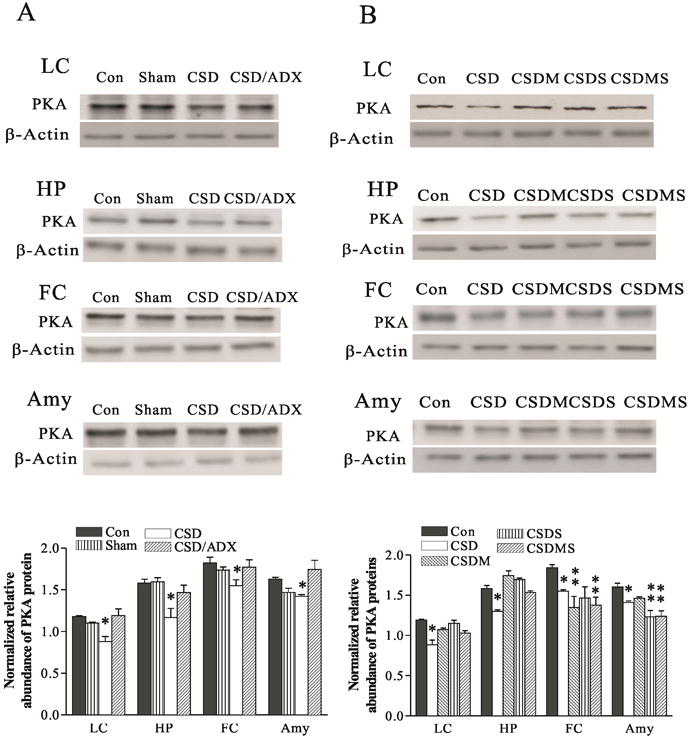

Abnormalities in the signal transduction system have been implicated in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorders (Akin et al., 2005). Some protein kinases are also involved in the functional activity of NET (Apparsundaram et al., 1998). However, there are not many reports about effects of chronic stress on the expression of these signal transduction-related molecules. In order to examine putative stress-induced changes in these proteins, we performed Western blotting to measure protein levels of PKA, PKC and pCREB in the LC and its terminal regions of the CSD rats that were used for the measurement of NET mentioned above. The results showed that CSD markedly decreases PKA protein levels in the LC (F3,19=6.66, p<0.01), hippocampus (F3, 23=5.90, p<0.05), frontal cortex (F3, 19=4.58, p<0.05) and amygdala (F3, 18=6.16, p<0.05). Further tests revealed that CSD decreased PKA protein levels in the LC by 25%, in the hippocampus by 26%, in the frontal cortex by 21% and in the amygdala by 23% (all p<0.05), respectively, compared with the controls (Fig. 5A). ADX abolished this CSD-induced reduction in PKA protein levels, indicating that intact adrenals are required for the CSD-induced decrease in PKA protein levels. As demonstrated in Fig. 5B, treatment with mifepristone and spironolactone, either alone or combination, abolished CSD-induced reduction of PKA protein levels in the LC and hippocampus. However, such blockade effect on PKA proteins caused by treatment with these antagonists did not appear in the frontal cortex and amygdala. In contrast, treatment with mifepristone and spironolactone, either alone or combination, also reduced PKA protein levels in the frontal cortex (both p<0.01) and in the amygdala (p<0.01), compared to the control (Fig. 5B). In the amygdala, the further reduced PKA levels caused by treatment with spironolactone alone or in combination with mifepristone did not reach the significant level when compared to that in the CSD group.

Figure 5.

Effects of CSD and adrenalectomy (A), as well as treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists (B) on PKA protein levels in the LC and its terminal regions. The upper figures in A and B show autoradiographs obtained by Western blotting of PKA in different regions (n=6-8/group). The lower graph in A and B shows quantitative analysis of band densities. Values of PKA bands were normalized to those of β-actin probed on the same blot. *P<0.05, ** p<0.01, compared to the control group. See Fig. 4 for abbreviations.

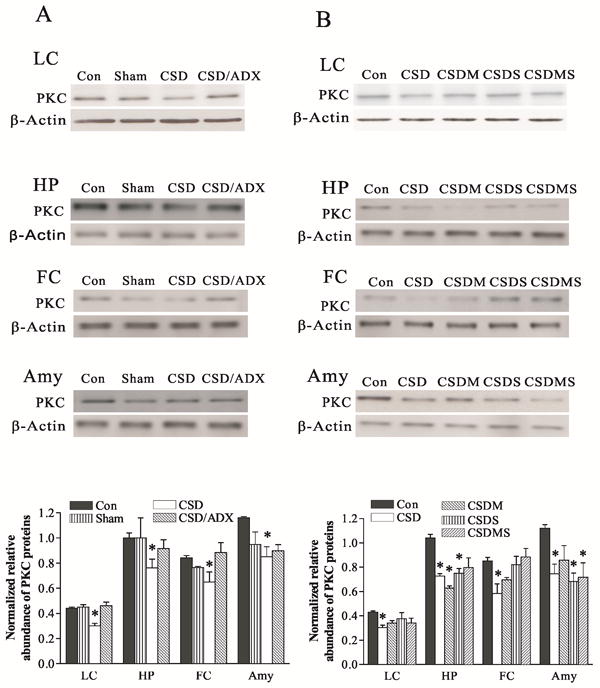

PKC protein levels in the LC, hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala were similarly decreased by CSD (F3,19=13.16, p<0.01 in the LC; F3,23=11.16 in the hippocampus; F3,23=7.48, p<0.01 in the frontal cortex, and F3,19=3.75, p<0.05 in the amygdala). CSD reduced PKC protein levels in the LC by 30%, in the hippocampus by 35%, in the frontal cortex by 34% and in the amygdala by 27%, respectively (all p<0.05). ADX eliminated the CSD-induced reduction of PKC protein levels (Fig. 6A). However, the effects of corticosteroid receptor antagonists on CSD-induced reduction of PKC protein levels were not consistent. While treatment with mifepristone and spironolactone, either alone or combination, abolished CSD-induced decreases of PKC protein levels in the LC and frontal cortex, such actions were not seen in the hippocampus and amygdala (Fig. 6B). In contrast, treatment with mifepristone caused a larger reduction of PKC protein levels in the hippocampus, while treatment with spironolactone alone or a combination of mifepristone and spironolactone significantly also reduced PKC protein levels in the amygdala.

Figure 6.

Effect of CSD and adrenalectomy (A), as well as treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists (B) on PKC protein levels in the LC and its terminal regions. The upper figures in A and B show autoradiographs obtained by Western blotting of PKC in different regions (n=6-8/group). The lower graph in A and B shows quantitative analysis of band densities. Values of PKC bands were normalized to those of β-actin probed on the same blot. *P<0.05, compared to the control group. See Fig. 4 for abbreviations.

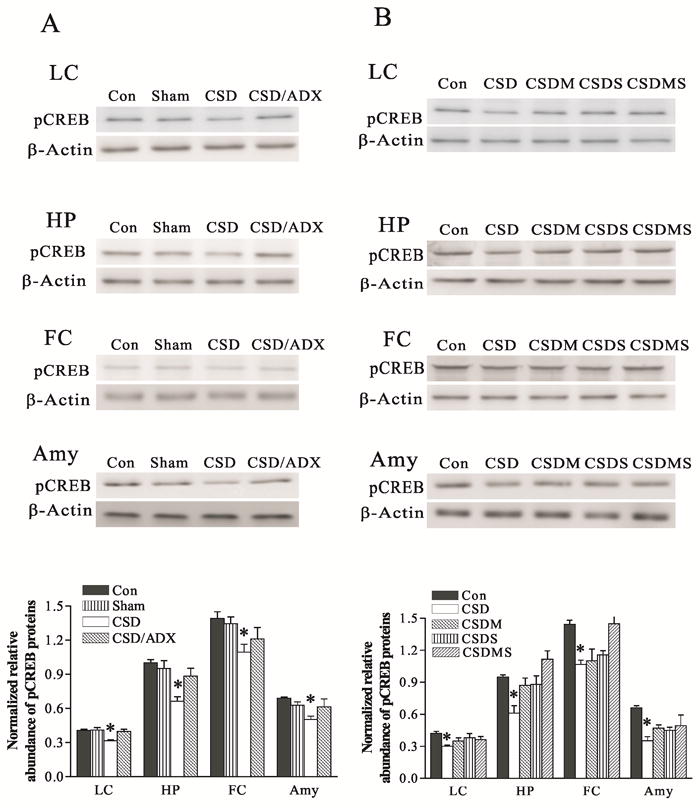

CSD also markedly decreased pCREB protein levels in these brain regions, similar to the response for PKA and PKC (F3,16=9.16, p<0.01 for the LC; F3,23=5.32, p<0.05 for the hippocampus; F3,19=3.75, p<0.05 for the frontal cortex, and F3, 19=3.67, p<0.05 for the amygdala). The reduction of pCREB induced by CSD was 22% in the LC, 31% in the hippocampus, and 24% in both the frontal cortex and amygdale (all p<0.05). These reductions were prevented by ADX (Fig. 7A). Treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists significantly reversed CSD-induced decreases in pCREB protein levels (F4,21=14.16, p<0.01 for the LC; F4,39=7.78, p<0.01 for the hippocampus; F4,25=7.10, p<0.01 for the frontal cortex, and F4, 29=3.45, p<0.05 for the amygdala). CSD-induced down-regulation of pCREB was totally abolished by treatment with mifepristone and spironolactone, either alone or in combination (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Effect of CSD and adrenalectomy (A), as well as treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists (B) on pCREB protein levels in the LC and its terminal regions. The upper figures in A and B show autoradiographs obtained by Western blotting of pCREB in different regions (n=6-8/group). The lower graph in A and B shows quantitative analysis of band densities. Values of pCREB bands were normalized to those of β-actin probed on the same blot. *P<0.05, compared to the control group. See Fig. 4 for abbreviations.

4. Discussion

In the present study, the CSD regimen significantly increased both mRNA and protein levels of NET in the rat LC, as well as NET protein levels in such LC terminal projection regions as the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala. This upregulated NET expression results in part from stress-induced release of corticosterone acting through corticosteroid receptors, as either adrenalectomy or treatment with the GR antagonist mifepristone and MR antagonist spironolactone, abolished or reduced the elevation of NET expression induced by CSD. Furthermore, CSD also significantly reduced the expression of PKA and PKC, as well as pCREB in these brain regions, indicating the possible involvement of these proteins in the CSD-induced up-regulation of NET. However, based on the results of the present study, whether corticosteroid receptors are involved in the regulation of CSD on PKA, PKC and pCREB expression remains to be elucidated, as the influence of corticosteroid receptor antagonists on CSD-induced reductions in these protein levels was not consistent in some regions. Taken together, the present study not only implies a functional linkage between chronic stress and noradrenergic neurons through upregulated NET expression, but also indicates similar putative alterations in signal transduction molecules occurred in experimental animals after chronic stress (Dwivedi et al., 2004a; Laifenfeld et al., 2005; McNamara and Lenox, 2004) and in patients suffered from major depression (Akin et al., 2005; Dwivedi et al., 2003; Pandey et al., 1997; Perez et al., 2001).

Both chronic psychosocial stress and dysfunctional noradrenergic transmission have been implicated as potential etiological factors in the development of depressive symptoms. It is likely that stressful events may trigger molecular interactions within the noradrenergic system, which subsequently contributes to the production of depressive symptoms. At present there is little direct clinical or basic research evidence to support this hypothesis. However, some previous reports indicate the possible presence of such interactions. First, animal studies demonstrated that stress-induced activation of the LC-NE system (Abercrombie and Jacobs, 1987) alters the release and metabolism of NE in the noradrenergic neuronal cell bodies and their terminal regions (Pacak et al., 1995; Smagin et al., 1997). Second, NET is fundamental for maintaining the accuracy of noradrenergic signaling by controlling both the duration and strength of NE signaling through its reuptake of synaptic NE (Barker and Blakely, 1995; Iversen, 1971). As only one NET protein has been identified at present, changes in its expression may be expected to significantly alter NE neurotransmission. Therefore, stress-induced activation of the LC-NE system most likely includes an effect on NET expression. The present study demonstrated that CSD upregulated the NET expression in central noradrenergic neurons. The results lead us to postulate that elevated NET induced by CSD may reduce the availability of NE in the noradrenergic synapses, which in turn results in a deficiency of NE-induced neuronal signal transduction. Thus dysregulation of noradrenergic activity may allow a homeostatic stress response to evolve into a pathological stress response (Goddard et al., 2010). However, as an increased expression of NET can present in both cell membranes and intracellular parts and only those in the cell membranes affect synaptic NE levels, a microdialysis experiment is warranted to verify this functional alteration.

CSD as a stress model of depression has been widely accepted and used in biomedical research for its relatively high predictive validity (Buwalda et al., 2005; Huhman, 2006). This animal model is characterized by relatively long-term behavioral changes with similarities to depressive symptoms such as anhedonia, as well as relatively congruent biochemical alterations (Huhman, 2006; Rygula et al., 2005). All these alterations can be reversed or attenuated with chronic administration of clinically effective antidepressant drugs (Becker et al., 2008; Keeney and Hogg, 1999; Von Frijtag et al., 2002). While the basic procedures for animal handling are similar, the main difference for this model from the literature is the time period of defeat session, which ranged from 3 days to 5 weeks (Abumaria et al., 2006; Bhatnagar and Vining, 2003; Rygula et al., 2005). In the present study, a paradigm of 4 weeks with variable defeat session schedules was used for the purpose to avoid the habituation of rats to a regular schedule. Sucrose consumption in the defeated rats, an analog of “anhedonia-like” symptoms in this stress paradigm, was reduced to about 50% of control baseline by CSD during whole experimental period. This diminished sucrose consumption and significantly increased plasma corticosterone levels (Fig. 1) further establish CSD as a useful and reliable model for mimicking some of the behavioral and endocrine alterations in clinical depression.

It is known that corticosterone secretion from the adrenal glands is regulated by the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Released corticosterone, through corticosteroid receptors (MRs and GRs), exerts a negative feedback on the HPA axis during stress. Accordingly, blockage of these receptors would cause an increased corticosterone level. However, plasma corticosterone levels are also influenced by other stress hormones such as the corticotropin releasing factor, ACTH and arginine vasopressio15-16n (De Kloet et al., 1998; Kovacs et al., 2000). Furthermore, corticosterone-caused suppressive effects mediated by corticosteroid receptors on the HPA axis not only depend on the stress modality: whether it is mild, moderate, or intensive; but also on the stress course: whether it is an acute or chronic (Pace and Spencer, 2005; Weidenfeld and Feldman, 1993). In addition, the doses of corticosteroid receptor antagonists used in experiments could affect such suppressive effect (Cole et al., 2000; Ratka et al., 1989; Spencer et al., 1998). Therefore, so far there were inconsistent observations. For example, stress-induced high plasma corticosterone levels were further exaggerated by treatment with either corticosteroid receptor antagonists alone or in combination (Ratka et al., 1989; Spencer et al., 1998). However, a no further change in plasma corticosterone levels was also reported in the animal stress models by similar treatments (Glavas et al., 2006; Moldow et al., 2005; Pace and Spencer, 2005; Weidenfeld and Feldman, 1993). In the present study, while plasma corticosterone levels in CSD rats treated with mifepristone or spironolactone alone were similarly increased as in CSD-alone rats, CSD rats treated with both mifepristone and spironolactone showed a lower plasma corticosterone level than that of the CSD-alone group. However, this reduction did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1B). These results demonstrate that corticosteroid receptor antagonists have no significant effect on CSD-induced adrenocortical activation, a result similar to those reported previously (Glavas et al., 2006; Moldow et al., 2005; Pace and Spencer, 2005; Weidenfeld and Feldman, 1993). Taken together, the present results suggest that both MRs and GRs did not play an important role in mediating suppressive effects of glucocorticoids on HPA axis function in the intense stimuli like CSD.

In addition, there are two interesting findings regarding the sucrose consumption test in these experiments. Firstly, treatment with mifepristone alone or in combination with spironolactone blocked the reduction of the sucrose consumption of CSD rats in the first and second week of CSD paradigm (Fig. 2). However, in the following two weeks of CSD, this effect disappeared and the rats exhibited the same reduction in sucrose consumption as that of untreated CSD rats. Previously, several clinical trials have demonstrated that corticosteroid receptor antagonists, especially mifepristone, can ameliorate depression symptoms in some depressed subjects (Belanoff et al., 2001; Berton and Nestler, 2006). In the present study, the ability of these antagonists to partially reverse the reduced sucrose consumption rate caused by CSD reveals a similar animal analog to such an antidepressant effect of these corticosteroid receptor antagonists. However, this antidepressant effect is relatively transient and cannot be maintained in the presence of continuous CSD. Secondly, ADX rats exhibited a significantly lower rate of sucrose consumption and a higher rate of water consumption, as compared to that of normal non-stressed control rats, which is in accordance with previous report (Brosvic et al., 1989). Over the course of CSD, this lower sucrose consumption rate continued. However, the higher water consumption rate disappeared in these ADX rats and they showed water consumption rate similar to those of intact CSD rats. While an increased water consumption rate in ADX rats before CSD regimen may represent a compensating reaction for reduced sucrose consumption, we do not have satisfactory explanation for changes of water consumption rate after CSD. It appears that the development of the normal sucrose consumption in intact rats and stress-induced sucrose consumption deficits are dependent upon the presence of normal corticosterone release. It is worth noting that although ADX-induced reductions in basal levels of sucrose consumption were reported in rats and mice (Lowery et al., 2010; Seidenstadt and Eaton, 1978), the current result of no further effect on sucrose consumption deficits after a CSD regimen in ADX rats conflicts with one report, in which sucrose solution consumption in ADX mice remained the same as that of normal mice after chronic mild stress (CMS) (Goshen et al., 2008). Nevertheless, this discrepancy is possibly due to different stress regimes (CSD vs. CMS) that were used in two experiments.

The elimination of CSD-induced upregulation of NET expression by ADX or treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists seems to conflict with above interpretation that the CSD-induced reduction of NE synaptic availability by increasing NET expression accounted for the development of sucrose consumption deficits, because by the end of CSD regimen the sucrose consumption in the corticosteroid receptor antagonist-treated rats was still lower, while the NET expression was returned to control levels by these antagonists. One possible explanation is that this phenomenon is consistent with the clinical observation that after treatment with antidepressants, which immediately change NE levels, 3-4 weeks are needed for clinically significant improvement of depressive symptoms. New experiments to examine the time course for antidepressant treatment and sucrose consumption deficit normalization after a CSD regimen are underway to explore the relationship between NET expression, antidepressant treatment and anhedonic states.

Abnormalities in several signal transduction systems have been implicated in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorders (Akin et al., 2005). These abnormalities may be related to mechanisms that stem from environmental disturbances to homeostasis such as chronic stress and are manifested through dysfunctional neurotransmitter systems. To examine the possible involvement of the signal transduction-related molecules in the effects of CSD on the expression of NET in rat brains, PKA, PKC and pCREB proteins were measured in the LC and its terminal regions such as the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdale in the same groups of animals as those to measure NET. The results showed that protein levels of PKA, PKC and pCREB were significantly reduced in all examined regions of CSD groups. Although stress-induced reduction of PKA, PKC and pCREB in the hippocampus and frontal cortex has been reported previously (Dwivedi et al., 2004a; Laifenfeld et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2009; McNamara and Lenox, 2004), this is the first report of CSD-induced reduction in all these proteins levels in the LC and amygdala. The present finding provides further preclinical evidence for the involvement of chronic stress in the etiology of depression. Deficiencies in PKA, PKC and pCREB have been an important characteristic of clinical depression. For example, reduced protein levels of PKA, PKC and pCREB have been found in both peripheral compartments and post-mortem brain tissues from depressive patients and suicide victims with depressive episodes (Akin et al., 2005; Dwivedi et al., 2003; Dwivedi et al., 2004b; Pandey et al., 1997; Perez et al., 2001). These abnormalities can be reversed by antidepressant treatment (Berton et al., 2006; Duman et al., 2001; Malberg et al., 2000; Mann et al., 1995; Nestler et al., 1989; Racagni et al., 1992; Tadokoro et al., 1998). The high congruence in regional reductions in the expression of these proteins in CSD and depressive patients is a reassuring indication of similar underlying molecular mechanisms.

In the present study, CSD-induced upregulation of NET expression and concomitant reduction PKA, PKC and pCREB were found in the same brain regions. In support of the hypothesis that there may be a possible relationship between these changes, the regulation of NET expression by intracellular signal molecules has been reported previously. The activation of PKA and PKC may directly phosphorylate NET, which in turn alters the expression and/or function of NET. It was reported that the human NET bears canonical phosphorylation sites for PKC and PKA on the putative cytoplasmic domains (Pacholczyk et al., 1991), a structural site for regulatory action. This PKA- and PKC-induced phosphorylation of NET has been demonstrated by many studies (Apparsundaram et al., 1998; Jayanthi et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 1998). For example, in vitro studies showed that cAMP analogue (8 Br-cAMP) or cAMP production stimulator (forskolin) induced a concentration-dependent decrease in uptake of [3H]NE (Bunn, 1992), NET activity and NET gene expression (Paczkowski et al., 1996). These effects can be inhibited by a protein kinase inhibitor (Paczkowski et al., 1996). Moreover, activation of PKC diminishes human NET activity via altered cell surface distribution of human NETs (Apparsundaram et al., 1998). Longer exposure to phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA; PKC agonist) resulted in decreased [3H]NE uptake and decreased binding of [3H]nisoxetine to NET (Meyer et al., 1998). Taken together, these findings revealed that the activation of PKA and PKC is related to the decreased expression and function of NET. Therefore, the diminished expression of PKA and PKC caused by CSD may allow upregulation of NET. Nevertheless, more experiments are needed to firmly establish this relationship. Thus far, there have not been any reports about the regulatory effect of pCREB on NET. However, given that pCREB plays an important role in the action of antidepressants (Sairanen et al., 2007; Sulser, 2002) and NET is a key factor for NE reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, their interaction is quite possible.

It is worthy to notice that as showed in Figs. 5B and 6B, treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists did not prevent CSD-induced reduction of PKA protein levels in the frontal cortex and amygdala, and PKC protein levels in the hippocampus and amygdala. In contrast, the same treatment abolished CSD-induced reduction of protein levels of PKA, PKC and pCREB in the LC, as well as CSD-induced reduction of pCREB protein levels in the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala (Fig. 7B). Currently we do not have satisfying explanation for whether such selective effect of corticosteroid receptor antagonists indicates that corticosteroid receptors were not involved in CSD’s effects on PKA and PKC in these brain regions. If it is true, this selective effect may be related to the complex structures of PKA and PKC. While PKA is composed of genetically distinct regulatory and catalytic subunits, each of which is coded by different genes, PKC also has different isoforms (Brandon et al., 1997; Robinson-White and Stratakis, 2002). More importantly, these subunits or isoforms have a distinct pattern of tissue distribution (Dwivedi and Pandey, 2011) and are modulated by glucocorticoids in an isoform-, or subunit-specific manner (Dwivedi and Pandey, 2000; Maddali et al., 2005). On the contrary, there is only one identified NET protein, which is coded by one gene (Pacholczyk et al., 1991). Therefore, this might be one reason why NET expression is more consistently regulated by CSD. Furthermore, many other signal transduction pathways including the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) are also involved in chronic stress (Galeotti and Ghelardini, 2011; Robinson-White and Stratakis, 2002). Many factors such as Ca2+ and diacylglycerol (DAG) influence the activation and expression of PKA and PKC (Robinson-White and Stratakis, 2002). Selective effects of glucocorticoids in different brain regions can be expected. However, since the present experiment is an initial step in our project, a direct link between CSD and these signal transduction proteins cannot be definitely established, only inferred. More experiments are needed for further elucidation of such relationship.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that CSD upregulated NET expression in the LC and its terminal regions. In this upregulation, stress-induced release of corticosterone acting through corticosteroid receptors plays a key role, as ADX and treatment with corticosteroid receptor antagonists block these effects of CSD. The upregulated NET may result in synaptic deficiency of NE, which links chronic stress with the activation of the noradrenergic system and subsequent development of depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the present study demonstrates that concomitant with increased NET expression, some important signal transduction proteins such as PKA, PKC and pCREB were significantly reduced in regional brain concentrations, a phenomenon also observed in brains of patients suffering from major depressive symptoms and in postmortem brains of suicide victims with depressive symptoms at the time of death. The reduction of PKA, PKC and pCREB may not only be related to CSD-induced analogs of depressive symptoms, but also be involved in the increased NET expression. Further studies are needed to elaborate this putative relationship.

Highlights.

Chronic stress and dysfunctional noradrenergic systems are involved in the depression.

We examine effects of chronic social defeat on NET and protein kinases in the brain.

CSD increases NET and reduces protein kinases in central noradrenergic neurons.

Changed NET and protein kinases may causally account for stress’ role for depression.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH grant MH080323 and NARSAD Young Investigator Award. The authors thank Mr. Hobart Zhu for his helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abercrombie ED, Jacobs BL. Single-unit response of noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus of freely moving cats. I. Acutely presented stressful and nonstressful stimuli. J Neurosci. 1987;7:2837–2843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-09-02837.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abumaria N, Rygula R, Havemann-Reinecke U, Ruther E, Bodemer W, Roos C, Flugge G. Identification of genes regulated by chronic social stress in the rat dorsal raphe nucleus. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:145–162. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9024-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akin D, Manier DH, Sanders-Bush E, Shelton RC. Signal transduction abnormalities in melancholic depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8:5–16. doi: 10.1017/S146114570400478X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisman H, Sklar LS. Catecholamine depletion in mice upon reexposure to stress: mediation of the escape deficits produced by inescapable shock. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1979;93:610–625. doi: 10.1037/h0077603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apparsundaram S, Galli A, DeFelice LJ, Hartzell HC, Blakely RD. Acute regulation of norepinephrine transport: I. protein kinase C-linked muscarinic receptors influence transport capacity and transporter density in SK-N-SH cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:733–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker E, Blakely R. Norepinephrine and serotonin transporters. Moleculartargets of antidepressant drugs. In: Bloom F, Kupfer D, editors. Psychopharmacology. A fourth generation of progress. Raven Press; New York: 1995. pp. 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Becker C, Zeau B, Rivat C, Blugeot A, Hamon M, Benoliel JJ. Repeated social defeat-induced depression-like behavioral and biological alterations in rats: involvement of cholecystokinin. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:1079–1092. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanoff JK, Flores BH, Kalezhan M, Sund B, Schatzberg AF. Rapid reversal of psychotic depression using mifepristone. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:516–521. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman RM, Narasimhan M, Miller HL, Anand A, Cappiello A, Oren DA, Heninger GR, Charney DS. Transient depressive relapse induced by catecholamine depletion: potential phenotypic vulnerability marker? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:395–403. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton O, McClung CA, Dileone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Graham D, Tsankova NM, Bolanos CA, Rios M, Monteggia LM, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science. 2006;311:864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1120972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton O, Nestler EJ. New approaches to antidepressant drug discovery: beyond monoamines. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:137–151. doi: 10.1038/nrn1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S, Vining C. Facilitation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to novel stress following repeated social stress using the resident/intruder paradigm. Horm Behav. 2003;43:158–165. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(02)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon EP, Idzerda RL, McKnight GS. PKA isoforms, neural pathways, and behaviour: making the connection. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosvic GM, Risser JM, Doty RL. No influence of adrenalectomy on measures of taste sensitivity in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1989;46:699–705. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90354-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW. Genetic and population perspectives on life events and depression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s001270050067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO, Hepworth C. Life events and endogenous depression. A puzzle reexamined. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:525–534. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070017006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunney WE, Jr, Davis JM. Norepinephrine in depressive reactions. A review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13:483–494. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01730060001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buwalda B, Kole MH, Veenema AH, Huininga M, de Boer SF, Korte SM, Koolhaas JM. Long-term effects of social stress on brain and behavior: a focus on hippocampal functioning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco GA, Van de Kar LD. Neuroendocrine pharmacology of stress. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463:235–272. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MA, Kalman BA, Pace TW, Topczewski F, Lowrey MJ, Spencer RL. Selective blockade of the mineralocorticoid receptor impairs hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis expression of habituation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:1034–1042. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui XJ, Vaillant GE. Antecedents and consequences of negative life events in adulthood: a longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:21–26. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E, Oitzl MS, Joels M. Brain corticosteroid receptor balance in health and disease. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:269–301. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado PL, Moreno FA. Role of norepinephrine in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(Suppl 1):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Nakagawa S, Malberg J. Regulation of adult neurogenesis by antidepressant treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:836–844. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00358-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y, Mondal AC, Shukla PK, Rizavi HS, Lyons J. Altered protein kinase a in brain of learned helpless rats: effects of acute and repeated stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2004a;56:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y, Pandey GN. Adrenal glucocorticoids modulate [3H]cyclic AMP binding to protein kinase A (PKA), cyclic AMP-dependent PKA activity, and protein levels of selective regulatory and catalytic subunit isoforms of PKA in rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y, Pandey GN. Elucidating biological risk factors in suicide: role of protein kinase A. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:831–841. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y, Rao JS, Rizavi HS, Kotowski J, Conley RR, Roberts RC, Tamminga CA, Pandey GN. Abnormal expression and functional characteristics of cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein in postmortem brain of suicide subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:273–282. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y, Rizavi HS, Shukla PK, Lyons J, Faludi G, Palkovits M, Sarosi A, Conley RR, Roberts RC, Tamminga CA, Pandey GN. Protein kinase A in postmortem brain of depressed suicide victims: altered expression of specific regulatory and catalytic subunits. Biol Psychiatry. 2004b;55:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeotti N, Ghelardini C. Regionally selective activation and differential regulation of ERK, JNK and p38 MAP kinase signalling pathway by protein kinase C in mood modulation. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavas MM, Yu WK, Weinberg J. Effects of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor blockade on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function in female rats prenatally exposed to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1916–1924. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavin GB, Tanaka M, Tsuda A, Kohno Y, Hoaki Y, Nagasaki N. Regional rat brain noradrenaline turnover in response to restraint stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;19:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard AW, Ball SG, Martinez J, Robinson MJ, Yang CR, Russell JM, Shekhar A. Current perspectives of the roles of the central norepinephrine system in anxiety and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:339–350. doi: 10.1002/da.20642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben-Menachem-Zidon O, Licht T, Weidenfeld J, Ben-Hur T, Yirmiya R. Brain interleukin-1 mediates chronic stress-induced depression in mice via adrenocortical activation and hippocampal neurogenesis suppression. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:717–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenisch B, Bilkei-Gorzo A, Caron MG, Bonisch H. Knockout of the norepinephrine transporter and pharmacologically diverse antidepressants prevent behavioral and brain neurotrophin alterations in two chronic stress models of depression. J Neurochem. 2009;111:403–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Bakos N, Rodriguiz RM, Caron MG, Wetsel WC, Liposits Z. Behavioral responses to social stress in noradrenaline transporter knockout mice: effects on social behavior and depression. Brain Res Bull. 2002;58:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00789-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Millar S, Kruk MR. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade inhibits aggressive behaviour in male rats. Stress. 1998;2:201–207. doi: 10.3109/10253899809167283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhman KL. Social conflict models: can they inform us about human psychopathology? Horm Behav. 2006;50:640–646. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang BH, Kunkler PE, Tarricone BJ, Hingtgen JN, Nurnberger JI., Jr Stress-induced changes of norepinephrine uptake sites in the locus coeruleus of C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice: a quantitative autoradiographic study using [3H]-tomoxetine. Neurosci Lett. 1999;265:151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen LL. Role of transmitter uptake mechanisms in synaptic neurotransmission. Br J Pharmacol. 1971;41:571–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1971.tb07066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi LD, Annamalai B, Samuvel DJ, Gether U, Ramamoorthy S. Phosphorylation of the norepinephrine transporter at threonine 258 and serine 259 is linked to protein kinase C-mediated transporter internalization. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23326–23340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney AJ, Hogg S. Behavioural consequences of repeated social defeat in the mouse: preliminary evaluation of a potential animal model of depression. Behav Pharmacol. 1999;10:753–764. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf J, Aghajanian GK, Roth RH. Increased turnover of norepinephrine in the rat cerebral cortex during stress: role of the locus coeruleus. Neuropharmacology. 1973;12:933–938. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(73)90024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs KJ, Foldes A, Sawchenko PE. Glucocorticoid negative feedback selectively targets vasopressin transcription in parvocellular neurosecretory neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3843–3852. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03843.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Palkovits M, Mitro A, Torda T, Mikulaj L. Catecholamines in individual hypothalamic nuclei of acutely and repeatedly stressed rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1977;23:257–267. doi: 10.1159/000122673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laifenfeld D, Karry R, Grauer E, Klein E, Ben-Shachar D. Antidepressants and prolonged stress in rats modulate CAM-L1, laminin, and pCREB, implicated in neuronal plasticity. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:432–441. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert G, Johansson M, Agren H, Friberg P. Reduced brain norepinephrine and dopamine release in treatment-refractory depressive illness: evidence in support of the catecholamine hypothesis of mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:787–793. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Ter Horst GJ, Wichmann R, Bakker P, Liu A, Li X, Westenbroek C. Sex differences in the effects of acute and chronic stress and recovery after long-term stress on stress-related brain regions of rats. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:1978–1989. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery EG, Spanos M, Navarro M, Lyons AM, Hodge CW, Thiele TE. CRF-1 antagonist and CRF-2 agonist decrease binge-like ethanol drinking in C57BL/6J mice independent of the HPA axis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1241–1252. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macunluoglu B, Arikan H, Atakan A, Tuglular S, Ulfer G, Cakalagaoglu F, Ozener C, Akoglu E. Effects of spironolactone in an experimental model of chronic cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddali KK, Korzick DH, Turk JR, Bowles DK. Isoform-specific modulation of coronary artery PKC by glucocorticoids. Vascul Pharmacol. 2005;42:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9104–9110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann CD, Vu TB, Hrdina PD. Protein kinase C in rat brain cortex and hippocampus: effect of repeated administration of fluoxetine and desipramine. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:595–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara RK, Lenox RH. Acute restraint stress reduces protein kinase C gamma in the hippocampus of C57BL/6 but not DBA/2 mice. Neurosci Lett. 2004;368:293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J, Wiedemann P, Okladnova O, Bruss M, Staab T, Stober G, Riederer P, Bonisch H, Lesch KP. Cloning and functional characterization of the human norepinephrine transporter gene promoter. J Neural Transm. 1998;105:1341–1350. doi: 10.1007/s007020050136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldow RL, Beck KD, Weaver S, Servatius RJ. Blockage of glucocorticoid, but not mineralocorticoid receptors prevents the persistent increase in circulating basal corticosterone concentrations following stress in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 2005;374:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa R, Tanaka M, Kohno Y, Noda Y, Nagasaki N. Regional responses of rat brain noradrenergic neurones to acute intense stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1981;14:729–732. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(81)90139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Terwilliger RZ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant administration alters the subcellular distribution of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in rat frontal cortex. J Neurochem. 1989;53:1644–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb08564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H, Mune T, Morita H, Daidoh H, Hanafusa J, Shibata T, Yamakita N, Yasuda K. Inhibition of aldosterone turn-off phenomenon following chronic adrenocorticotropin treatment with in vivo administration of antiglucocorticoid and antioxidants in rats. Eur J Endocrinol. 1995;133:578–584. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1330578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacak K, Palkovits M, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Stress-induced norepinephrine release in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and pituitary-adrenocortical and sympathoadrenal activity: in vivo microdialysis studies. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1995;16:89–150. doi: 10.1006/frne.1995.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace TW, Gaylord RI, Jarvis E, Girotti M, Spencer RL. Differential glucocorticoid effects on stress-induced gene expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and ACTH secretion in the rat. Stress. 2009;12:400–411. doi: 10.1080/10253890802530730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace TW, Spencer RL. Disruption of mineralocorticoid receptor function increases corticosterone responding to a mild, but not moderate, psychological stressor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E1082–1088. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00521.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacholczyk T, Blakely RD, Amara SG. Expression cloning of a cocaine- and antidepressant-sensitive human noradrenaline transporter. Nature. 1991;350:350–354. doi: 10.1038/350350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paczkowski NJ, Vuocolo HE, Bryan-Lluka LJ. Conclusive evidence for distinct transporters for 5-hydroxytryptamine and noradrenaline in pulmonary endothelial cells of the rat. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1996;353:423–430. doi: 10.1007/BF00261439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey GN, Dwivedi Y, Pandey SC, Conley RR, Roberts RC, Tamminga CA. Protein kinase C in the postmortem brain of teenage suicide victims. Neurosci Lett. 1997;228:111–114. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00378-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES. Life events, social support and depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1994;377:50–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez J, Tardito D, Racagni G, Smeraldi E, Zanardi R. Protein kinase A and Rap1 levels in platelets of untreated patients with major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6:44–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racagni G, Brunello N, Tinelli D, Perez J. New biochemical hypotheses on the mechanism of action of antidepressant drugs: cAMP-dependent phosphorylation system. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25:51–55. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratka A, Sutanto W, Bloemers M, de Kloet ER. On the role of brain mineralocorticoid (type I) and glucocorticoid (type II) receptors in neuroendocrine regulation. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;50:117–123. doi: 10.1159/000125210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JM, de Kloet ER. Two receptor systems for corticosterone in rat brain: microdistribution and differential occupation. Endocrinology. 1985;117:2505–2511. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-6-2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter S, Llewellyn-Smith I, Dinh TT. Subgroups of hindbrain catecholamine neurons are selectively activated by 2-deoxy-D-glucose induced metabolic challenge. Brain Res. 1998;805:41–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-White A, Stratakis CA. Protein kinase A signaling: “cross-talk” with other pathways in endocrine cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;968:256–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario LA, Abercrombie ED. Individual differences in behavioral reactivity: correlation with stress-induced norepinephrine efflux in the hippocampus of Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Res Bull. 1999;48:595–602. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum LA, Coplan JD, Friedman S, Bassoff T, Gorman JM, Andrews MW. Adverse early experiences affect noradrenergic and serotonergic functioning in adult primates. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;35:221–227. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)91252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak M, Kvetnansky R, Jelokova J, Palkovits M. Effect of novel stressors on gene expression of tyrosine hydroxylase and monoamine transporters in brainstem noradrenergic neurons of long-term repeatedly immobilized rats. Brain Res. 2001;899:20–35. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rygula R, Abumaria N, Flugge G, Fuchs E, Ruther E, Havemann-Reinecke U. Anhedonia and motivational deficits in rats: impact of chronic social stress. Behav Brain Res. 2005;162:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen M, O’Leary OF, Knuuttila JE, Castren E. Chronic antidepressant treatment selectively increases expression of plasticity-related proteins in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Neuroscience. 2007;144:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenstadt RM, Eaton KE. Adrenal and ovarian regulation of salt and sucrose consumption. Physiol Behav. 1978;21:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(78)90086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smagin GN, Zhou J, Harris RB, Ryan DH. CRF receptor antagonist attenuates immobilization stress-induced norepinephrine release in the prefrontal cortex in rats. Brain Res Bull. 1997;42:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(96)00368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer RL, Kim PJ, Kalman BA, Cole MA. Evidence for mineralocorticoid receptor facilitation of glucocorticoid receptor-dependent regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2718–2726. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer RL, Miller AH, Moday H, Stein M, McEwen BS. Diurnal differences in basal and acute stress levels of type I and type II adrenal steroid receptor activation in neural and immune tissues. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1941–1950. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.8404640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer RL, Young EA, Choo PH, McEwen BS. Adrenal steroid type I and type II receptor binding: estimates of in vivo receptor number, occupancy, and activation with varying level of steroid. Brain Res. 1990;514:37–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90433-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulser F. The role of CREB and other transcription factors in the pharmacotherapy and etiology of depression. Ann Med. 2002;34:348–356. doi: 10.1080/078538902320772106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro C, Kiuchi Y, Yamazaki Y, Oguchi K, Kamijima K. Effects of imipramine and sertraline on protein kinase activity in rat frontal cortex. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;342:51–54. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01530-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant C, Bebbington P, Hurry J. The role of life events in depressive illness: is there a substantial causal relation? Psychol Med. 1981;11:379–389. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700052193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Frijtag JC, Van den Bos R, Spruijt BM. Imipramine restores the long-term impairment of appetitive behavior in socially stressed rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;162:232–238. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenfeld J, Feldman S. Glucocorticoid feedback regulation of adrenocortical responses to neural stimuli: role of CRF-41 and corticosteroid type I and type II receptors. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;58:49–56. doi: 10.1159/000126511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Gainetdinov RR, Wetsel WC, Jones SR, Bohn LM, Miller GW, Wang YM, Caron MG. Mice lacking the norepinephrine transporter are supersensitive to psychostimulants. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:465–471. doi: 10.1038/74839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafar HM, Pare WP, Tejani-Butt SM. Effect of acute or repeated stress on behavior and brain norepinephrine system in Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats. Brain Res Bull. 1997;44:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu MY, Kim CH, Hwang DY, Baldessarini RJ, Kim KS. Effects of desipramine treatment on norepinephrine transporter gene expression in the cultured SK-N-BE(2)M17 cells and rat brain tissue. J Neurochem. 2002;82:146–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond MJ, Harvey JA. Resistance to central norepinephrine depletion and decreased mortality in rats chronically exposed to electric foot shock. J Neurovisc Relat. 1970;31:373–381. doi: 10.1007/BF02312738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]