Abstract

Background

Mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) cause a variety of pathologic states in human patients. Development of animal models harboring mtDNA mutations is crucial to elucidating pathways of disease and as models for preclinical assessment of therapeutic interventions.

Scope of Review

This review covers the knowledge gained through animal models of mtDNA mutations and the strategies used to produce them. Animals derived from spontaneous mtDNA mutations, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), nuclear translocation of mitochondrial genes followed by mitochondrial protein targeting (allotopic expression), mutations in mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma, direct microinjection of exogenous mitochondria, and cytoplasmic hybrid (cybrid) embryonic stem cells (ES cells) containing exogenous mitochondria (transmitochondrial cells) are considered.

Major Conclusions

A wide range of strategies have been developed and utilized in attempts to mimic human mtDNA mutation in animal models. Use of these animals in research studies has shed light on mechanisms of pathogenesis in mitochondrial disorders, yet methods for engineering specific mtDNA sequences are still in development.

General Significance

Research animals containing mtDNA mutations are important for studies of the mechanisms of mitochondrial disease and are useful for development of clinical therapies.

Keywords: Animal modeling, mitochondria, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), mitochondrial disease, transmitochondrial animals, xenomitochondrial mice

1. Introduction

Since the mitochondrial genome codes for proteins integral to energy production, it is not surprising that mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) give rise to disease. As there are currently no cures for a spectrum of mtDNA associated human pathologies, in vivo mtDNA mutation modeling is of critical importance; both to deepen understanding of disease mechanisms and to provide tools for preclinical testing of therapeutic interventions. Animal modeling and genetic engineering of mtDNA mutations have trailed nuclear transgenesis due to a range of cellular and physiological distinctions. Yet, several strategies have been employed to produce a number of animal models that yield insights into various aspects of mtDNA pathogenesis.

2. Mitochondrial DNA

The 16.6 kb human mitochondrial genome contains 37 genes of which 13 code for structural proteins [1]. Seven are subunits in complex I, one in complex III, three in complex IV, and two in complex V. These 13 protein-coding genes are transcribed [2] and translated [3] inside the mitochondrial matrix. The 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and 2 ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) encoded by the mtDNA facilitate translation. mtDNA is almost exclusively maternally inherited [4], though extremely rare paternal inheritance has been reported [5].

Normally, only one mtDNA sequence exists within an individual organism or cell, a state known as homoplasmy. The phenomenon of two or more distinct mtDNA species existing together is referred to as heteroplasmy. mtDNA has a higher rate of nucleotide substitution than nuclear DNA [6]. In humans, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the mitochondrial genome are widespread throughout the population. An individual’s mtDNA sequence, assuming homoplasmy, is referred to as that person’s mitochondrial haplotype. Groups of similar haplotypes, such as those that occur in discrete geographical regions (e.g., Scandinavia vs. Southern Europe), constitute haplogroups. mtDNA sequences are routinely used for identification purposes in forensic sciences [7]. Haplogroup divergences can be used to track population movements throughout evolution [8]. The majority of mtDNA polymorphisms in humans appear to be functionally neutral. However, whole mtDNA haplogroups have been associated with functional differences, including energetic response to different climates and risk factors to various clinical manifestations [9].

3. mtDNA mutations in human disease

Since the mitochondrial genome codes for proteins integral to energy production, it is not surprising that some mtDNA mutations give rise to pathologic states. A correlation between variations in mitochondrial genome sequence and pathologic states was first hypothesized in 1972 with laboratory confirmation over 15 years later [10–13]. Greater than 200 distinct pathogenic mutations have since been reported in the human mitochondrial genome [14, 15]. Mutations in mtDNA can be inherited maternally or arise spontaneously in somatic cells and contribute to a wide variety of pathologic conditions [16]. The location of a mutation within the mitochondrial genome can have a great impact on a resulting pathogenic phenotype. Mutations found in protein coding genes affect the function or expression of that gene product only, whereas mutations found in tRNAs or rRNAs can have a profound negative impact on the translation of all 13 mtDNA encoded proteins.

Prevalence of pathologies involving mitochondrial dysfunction (including those resulting from mutations in nuclear genes) is estimated at 1 in 5000 [17]. This is likely an underestimate due to the difficulty in diagnosing mitochondrial pathologies [18].

There are currently no cures for mtDNA associated pathologies. Treatment for diseases arising from mtDNA mutations is largely palliative. A ketogenic diet is often prescribed along with various antioxidants [19]. While anecdotal evidence abounds in support of various behavioral, dietary and nutraceutical interventions, few controlled clinical trials have been conducted to date and those yielded mostly negative results [20].

4. Animal modeling of mitochondrial dysfunction

Achieving a greater understanding of the mechanisms of pathogenesis in human mitochondrial diseases as well as producing disease models for preclinical testing of therapeutic interventions make the creation of animal models of mitochondrial mutation desirable. Several animal models of mitochondrial dysfunction have been developed [21]. Of these, a few mouse models target mutations in nuclear encoded OXPHOS subunit genes including Complex I subunit NDUFS4 [22, 23] and cytochrome c [24]. While nuclear gene modeling has led to advances in understanding mitochondrial biology and disease physiology, animal models of pathologies associated with mutations in the mitochondrial genome have been much slower in development.

The comparative lack of animal models of mtDNA mutation arises mainly from the difficulty of engineering the mitochondrial genome. Successful efforts to directly model mtDNA mutations must overcome several major hurdles:

Engineered mtDNA genomes must be able to pass through the two lipid bilayer membranes of mitochondria [25].

To achieve a functional level of heteroplasmy, mutations must be targeted to a significant portion of the hundreds to thousands of copies of the mitochondrial genome in each cell [26].

Although naturally occurring recombination between differing mtDNA species was shown to occur [27], using this as a tool for engineering mtDNA mutations is not yet feasible as the mechanisms and regulation of mtDNA recombination are not well understood.

Introduced mtDNA molecules that result in decreased respiratory capability often display a selective disadvantage and are selectively eliminated [28, 29].

4.1 Spontaneous pathogenic mtDNA mutations in animals

While neither genoyptically nor phenotypically equivalent to human mtDNA mutations, animal models of spontaneous mtDNA mutations display similarities which are useful in understanding mechanisms of mtDNA-related disease pathogenesis. The BHE/Cdb rat model of spontaneous mtDNA mutation possesses two base substitutions in the ATP6 gene resulting in replacement of an aspartate residue with asparagine at position 101 and serine for leucine at position 129. These rats display decreased rates of ATP synthesis and decreased oligomycin sensitivity. Additionally, BHE/Cdb rats exhibit multiple phenotypes that mimic type II diabetes, including fatty liver, increased lipogenic and gluconeogenic activity and high rates of renal failure [30, 31].

The G14474A mutation of the canine mitochondrial genome was identified in two distinct lineages (Australian cattle dog and Shetland sheepdog) [32]. This mutation results in a valine to methionine amino acid substitution at position 98 of cytochrome b. All dogs carrying the mutation displayed a variable but progressive neurological degeneration with spongiform encephalomyelopathy similar to human patients with Kearns-Sayre Syndrome.

A maternal lineage of golden retrievers in Sweden was described with chronic progressive sensory ataxic neuropathy [33]. Genetic analysis revealed a heteroplasmic single nucleotide deletion at position 5304 in the mitochondrial tyrosine tRNA gene [34]. Affected dogs displayed a decreased rate of ATP production and decreased oxidative phosphorylation complex I and complex IV enzyme activities.

While animal models of spontaneous mtDNA mutation display some characteristic phenotypes suggestive of human mitochondrial disease, the mutations in question are not identical to those seen in human disease. Therefore, in addition to animal models resulting from de novo mtDNA mutations, other models are needed to further advance understanding of the varied mechanisms by which human mtDNA mutation results in disease.

4.2 Somatic cell nuclear transfer

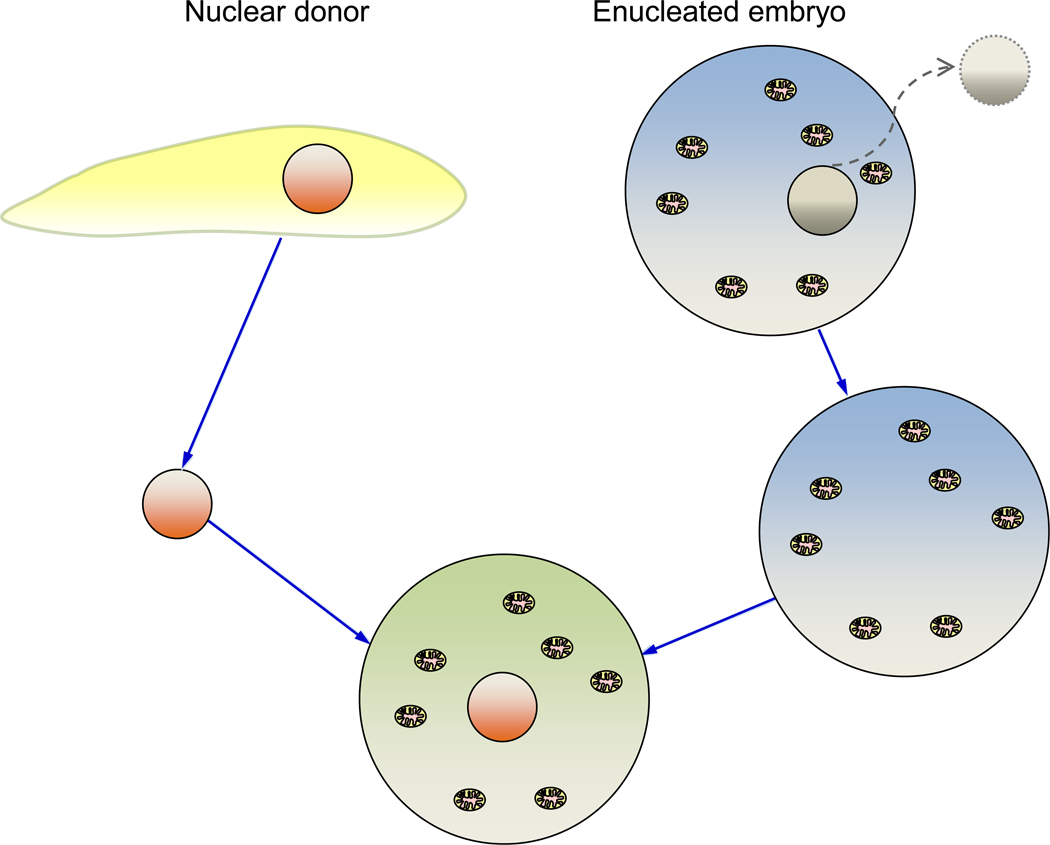

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) involves transplanting the nucleus from a somatic cell into an enucleated zygote (Figure 1) [35]. Cloned animals resulting from this process derive their nuclear genome from the donated nucleus and mitochondrial genome from the recipient embryo [36]. In this manner, mtDNAs from different strains/breeds or even closely related species [37] can be introduced onto a given nuclear genetic background. Animals produced by SCNT are often heteroplasmic for both nuclear donor and embryo recipient mitochondrial genomes [38]. Low efficiency in SCNT is exacerbated when heteroplasmic mtDNAs are introduced [39, 40]. Epigenetic disruption in animals derived from SCNT causes a variety of abnormalities that has little to do with mtDNA populations [41]. Since these epigenetic changes are not seen in offspring of cloned animals, in contrast to studies with founder animals, effects of mtDNA heteroplasmy can be readily assessed in subsequent offspring and their descendants.

Figure 1.

Creation of Cybrid Cells via Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT). Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT) is performed by transferring a nucleus isolated from a somatic cell (or the intact somatic cell) into an enucleated zygote. This technology was developed and used to produce both homoplasmic and heteroplasmic cybrid models.

4.3 Allotopic expression

The mitochondrial genome in animals is thought to have greatly reduced in size over the course of evolution as mitochondrial genes have translocated to the nucleus [42]. Experimentally duplicating the natural evolutionary process of mtDNA movement to the nucleus in a directed fashion by expressing a recombinant mitochondrial gene from the nuclear compartment is termed allotopic expression (Figure 2) [43]. Allotopic expression is a potential strategy for gene therapy in diseases resulting from mtDNA mutations [44–46], being most relevant to treating those diseases resulting from mutations in protein coding genes. Mitochondrial localization of an allotopically expressed wildtype protein could reduce the ratio of mutant:wildtype proteins present within mitochondria, resulting in improvement of mitochondrial function. Using this approach to address tRNA or rRNA mutations would require allotopic expression of all 13 mitochondrial protein encoding genes. While more challenging, this strategy was proposed as a method for combating aging by eliminating the need for oxidatively fragile mtDNA [46].

Figure 2.

Nuclear Expression and Subsequent Mitochondrial Transport of a Recombinant Mitochondrial Gene (Allotopic Expression). Allotopic expression of a mitochondrial gene occurs as the coding sequence is engineered to contain nuclear codons and is cloned downstream of a mitochondrial transport signal (MTS). The transgenic construct integrates into the nuclear genome, is transcribed in the nucleus, and translated in the cytoplasm. The nascent protein is translocated to the mitochondria via the MTS. In this manner, mtDNA mutations can be modeled via production of recombinant, allotopically expressed mtDNA genes.

Allotopic expression of a mitochondrial gene was first described in 1986 [47]. Here, a synthetic Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATP8 gene was cloned downstream of the N-terminal mitochondrial targeting signal (MTS) of the ATP9 gene of Neurospora crassa. Protein expressed from this transgene construct localized to yeast mitochondria.

Nuclear expression of mitochondrial targeted recombinant ATP6 was previously reported in human cells in vitro, in which a recoded, wildtype gene expressed from the nucleus overcame a metabolic deficiency caused by the T8993G mutation [48]. While the efficiency of mitochondrial import of the recombinant ATP6 protein was low, a subsequent study described allotopic expression of ATP6 using a similar plasmid where the T8993G mutation had been introduced [49]. Cybrid cells containing wildtype mtDNA were transfected with the mutant ATP6 plasmid and were shown to have diminished respiratory function compared to cells that were mock transfected. Thus, allotopically expressed mutant ATP6 is capable of effecting disruption of ATP synthase activity in vitro.

A separate report focused on allotopically expressed ATP6 in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells [50]. An engineered nuclear coded ATP6 containing a mutation resulted in resistance to the mitochondrial poison oligomycin. CHO cells expressing this transgene were able to grow in high concentrations of oligomycin whereas wildtype cells quickly died at much lower oligomycin concentrations.

Allotopic expression of mitochondrial encoded ND4 in the murine eye was reported. The G11778A mutation in human mtDNA results in Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON). Wildtype and mutant (G11778A) versions of ND4 gene constructs were created with upstream mitochondrial localization signals and downstream epitope tags. Intraocular injections of recombinant AAV viruses containing nuclear coded ND4 genes were performed. Recombinant ND4 proteins localized to mitochondria of retinal ganglion cells. Expression of mutated but not wildtype ND4 proteins resulted in increased ROS production, apoptosis and progressive retinal and optic nerve degeneration [51, 52]. Preclinical gene therapy studies using allotopically expressed wildtype ND4 from an AAV2 vector found high efficiency of gene delivery and a good safety profile, suggesting that human clinical use of similar vectors in patients suffering from LHON might be feasible [52]. Similarly, the G11778A human ND4 gene was allotopically expressed in the rat eye using in vivo electroporation resulting in significant retinal ganglion cell loss and vision impairment. Subsequent allotopic expression of the wildtype version of the gene reversed the deleterious effects of the mutant [53]. Human clinical trials testing safety and efficacy of this gene therapy construct are currently being planned [54].

4.4 Polymerase gamma mutants

DNA polymerase gamma (POLG) catalyzes mtDNA replication and possesses 3’-5’ exonuclease activity as part of its proofreading function of nascent mtDNA. Two groups reported mouse models in which exonuclease activity was ablated in POLG [55, 56]. The POLG in these mice is unable to proofread newly synthesized mtDNA, resulting in a higher rate of random and progressively accumulating mutations. These so-called mitochondrial mutator mice display several phenotypic characteristics indicative of early aging including increased apoptosis, increased oxidative damage, cardiomyopathy, hair loss, graying, kyphosis, weight loss, and decreased life span. The cardiac phenotype of these mice is due, at least partially, to oxidative stress. Mice homozygous for the POLG mutation crossed with mice overexpressing a catalase transgene yielded offspring that displayed reduced severity of the cardiomyopathy phenotype seen in POLG mutant mice [57]. Neural-specific POLG mutant mice display retinal dysfunction and high susceptibility to injury in retinal neurons [58].

4.5 Direct injection of mitochondria into embryos

Among the earliest attempts to directly manipulate the cellular mitochondrial content with an eye towards animal modeling were experiments in which mitochondria were microinjected into mouse embryos (Figure 3) [59]. The transfer of mitochondria from an evolutionarily divergent species (xenomitochondrial transfer) is postulated to result in mitochondrial dysfunction due to structural mismatches between the nuclear encoded respiratory subunits of one species and the mitochondrial encoded subunits of the other [28, 60]. Mitochondria isolated from Mus spretus (2 million years diverged from Mus musculus domesticus) were injected into M. m. domesticus zygotes. All embryos that developed to blastocyst stage contained detectable levels of M. spretus mtDNA. When embryos containing M. spretus mitochondria were transferred to pseudopregnant females and allowed to develop to term, M. spretus mitochondria were detected in resulting weanling mice [61]. Germline inheritance of M. spretus mitochondria was detected in two offspring of a female founder mouse with low heteroplasmy levels. Further breeding did not result in detectable levels of M. spretus mtDNA in any pups. These results suggest selective elimination of M. spretus mtDNA in favor of wildtype (M. m. domesticus) mitochondrial populations.

Figure 3.

Microinjection of Exogenous Mitochondria into Mouse Zygotes. Exogenous mitochondria (light colored) microinjected directly into the cytoplasm of a pronuclear stage mouse embryo containing endogenous mitochondria results in creation of a heteroplasmic state within the developing embryo and resulting mice.

In another study, a smaller mtDNA genome was hypothesized to gain a competitive advantage in DNA replication, as less time and energy would be required to replicate the smaller genome. A 6.5kb circular mtDNA molecule was created containing mitochondrial origins of replication and this recombinant mtDNA was electroporated into isolated mitochondria [62]. Electroporated mitochondria were shown to respire normally via oxygen consumption analysis and to contain detectable amounts of 6.5kb mtDNA by PCR analysis. Mitochondria containing 6.5kb mtDNAs were injected into pronuclear-stage zygotes yet no liveborn offspring were produced that harbored the deletion mutant mtDNA (Irwin and Pinkert, unpublished data, 2001).

4.6 Rho-zero (ρ0) cells

With an inability to produce long-term germline competent transmitochondrial mice via direct mitochondrial injection, it became clear that production of in vivo models of mtDNA mutations, either heteroplasmic or homoplasmic, required alternative technologies. One such strategy utilized cellular depletion of endogenous mtDNAs prior to introduction of foreign mitochondria. Cell lines lacking mtDNA (rho-zero, ρ0) were developed by incubation in ethidium bromide [63]. After several weeks of culture in ethidium bromide, cells became dependant on glycolysis for ATP production and required supplementation with uridine and pyruvate. Introduction of exogenous mitochondria restored aerobic respiration, followed by selection in medium lacking uridine and pyruvate. While treatment of immortalized cell lines with ethidium bromide resulted in serviceable ρ0 cell lines, the DNA intercalating, mutagenic properties of ethidium bromide made this chemical unsuitable for use in ES cells in the production of viable animals. An alternative method for producing ρ0 cells utilized the fluorescent dye rhodamine-6G [64]. This molecule removes mitochondrial populations by acting as an inhibitor of ATP synthase [65].

4.7 Cytoplasmic hybrids

Depopulation of endogenous mitochondria from ES cells prior to creation of the first transmitochondrial mice was performed using rhodamine-6G [66]. The creation of cybrid ES cell lines was a seminal development in mtDNA modeling. A cybrid cell is the fusion of a cytoplast (enucleated cell) to an intact cell (often ρ0) to produce a single cell with mixed mitochondrial populations (Figure 4) [63, 67]. Production of cybrid cell lines from an immortalized cell line enables easy propagation [25, 68]. The fusion of cytoplasts from patients with mitochondrial dysfunction with immortalized cell lines allows characterization of the biochemical phenotypes of cell lines containing specific mtDNA mutations. This approach also provides a uniform nuclear background for studies using cytoplasts made from different individuals, eliminating confounding nuclear variables [69]. Application of this technology to mouse whole-animal modeling utilizes murine embryonic stem cells (ES cells) in lieu of an immortalized cell line.

Figure 4.

Creation of Cybrid Cells via Cell Fusion. Cytoplasmic hybrid (cybrid) cells are produced when a ρ0 cell (devoid of mtDNA) is fused with an enucleated cytoplast. The resulting cell derives its nuclear genome from the ρ0 cell and its mitochondrial genome from the cytoplast. The use of murine embryonic stem (ES) cells as mitochondrial donor cells has led to the creation of transmitochondrial mouse models.

4.8 Transmitochondrial mice

The first mouse models applying cybrid transmitochondrial technologies in ES cells utilized cells with cytoplasmically (mitochondrial) conferred resistance to the antibiotic chloramphenicol [66, 70]. In these studies, chimeric mice developed cataracts and decreased retinal function. Offspring of female chimerae harboring the mutant mtDNA were runted with severe myopathy and cardiomyopathy. All mutant offspring died perinatally with one exception that lived 11 days [71].

Another mouse model of mtDNA mutation made use of ES cell cybrids heteroplasmic for a large-scale mtDNA deletion [72, 73]. The mutant mitochondrial genome lacked 4696 nucleotides including all or a portion of the ATP8, ATP6, COIII, ND3, ND4L, ND4 and ND5 genes along with several tRNA genes. Offspring of chimeric mice displayed decreased cytochrome oxidase activity in skeletal muscle and renal failure.

A recent transmitochondrial mouse modeling effort introduced a mtDNA genome with two mutations as a strategy for analyzing changes in heteroplasmy across generations [29]. The more severe mutation (13885insC) resulted in truncation of ND6 protein at position 79. The other, less severe, mutation (T6598C) substituted a conserved valine with alanine at position 421 in the COI protein. Using Rhodamine-6G-treated female ES cells fused with cytoplasts carrying the mutant mtDNA, one clone was found to be homoplasmic for the COI mutation, but was heteroplasmic for the mutant ND6 gene and a revertant gene that coded for the wildtype ND6 protein. This clone was used to produce chimeric mice. One germline female mouse resulted from breeding founder chimerae. This mouse displayed no gross phenotypic abnormalities while alive and gave birth to several litters of pups, but several tissues displayed decreased complex I and complex IV activities upon necropsy. The proportion of heteroplasmy was tracked in the female lineage of this mouse. With each successive generation, heteroplasmy of mutant ND6 mtDNA decreased until it was undetectable within four generations.

4.9 Xenomitochondrial modeling

Xenomitochondrial cybrids allow study of general mitochondrial polymorphism in lieu of specifically engineered mtDNA mutations. Introduction of mitochondria from an evolutionarily divergent species into a cell is hypothesized to create a functional mismatch due to suboptimal interaction of respiratory subunits encoded by the introduced mtDNA with respiratory subunits encoded by the nuclear genome (Figure 5). Proof of concept experiments included production of xenomitochondrial cybrids derived from human cell lines supplemented with mitochondria from gorilla, chimpanzee or pygmy chimpanzee cytoplasmic donors [74]. These xenomitochondrial cybrids exhibited mitochondrial deficiencies in complex I activity [75]. Work with M. m. domesticus cybrids containing Rattus norvegicus mtDNA demonstrated severely impaired mitochondrial function, including elevated lactate production, impaired state III respiration and respiratory enzyme deficiencies [76]. Studies of xenomitochondrial cybrid lines demonstrated viability of xenomitochondrial cybrids as models of mitochondrial dysfunction and provided insight into the biochemical pathology of mitochondrial dysfunction. These studies provided useful in vitro data and paved the way for in vivo xenomitrochondrial modeling [25].

Figure 5.

Hypothesized Suboptimal Protein Interactions in Respiratory Complexes through Xenomitochondrial Cybrid Modeling. Suboptimal protein-protein interactions between respiratory subunits of divergent species are hypothesized to lead to mitochondrial dysfunction in murine xenomitochondrial cybrids.

Xenomitochondrial cybrids with Mus terricolor mitochondria within M. m. domesticus cells were hypothesized to exhibit a deficit in mitochondrial function similar to that seen in the previous xenomitochondrial studies. A less extreme defect was anticipated, as M. terricolor only diverged from M. m. domesticus six million years ago, as opposed to greater than ten million years ago for R. norvegicus [28, 60, 74, 75, 77]. Early in vitro studies showed a relationship between increased lactate production (indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction) and evolutionary divergence of introduced mitochondria in xenomitochondrial cell lines [77]. Sequencing of M. terricolor mtDNA revealed 159 amino acid changes compared to M. m domesticus. The 12S and 16S rRNAs had 31 and 124 nucleotide changes, respectively, while tRNA homology ranged from 93%–100% [60].

The potential for in vivo xenomitochondrial studies to provide inroads into understanding the mechanisms of mitochondrial disease encouraged the production of mouse models. Ease of manipulation of mouse embryos and genetics made the mouse an obvious choice for development of xenomitochondrial models of mitochondrial dysfunction. Injection of female M. m domesticus cybrid ES cells harboring mitochondria derived from an evolutionarily divergent murine species, M. terricolor, into blastocysts led to the creation of chimeric founder xenomitochondrial mice [78–80]. Xenomitochondrial mice were produced by injection of 129S6/SvEvTac (129S6) ES cells harboring M. terricolor mtDNA into host C57BL/6NTac blastocysts, followed by breeding chimeric females to C57BL/6NTac males (B6NTac(129S6)-mtM. terricolor/Capt; line D7). This resulted in a maternal lineage of homoplasmic xenomitochondrial mice (designated “D7”) derived from cybrid ES cells, which was used in preliminary phenotypic characterization [28, 80].

D7 xenomitochondrial mice do not display obvious gross phenotypic abnormalities [81]. Parental background strain was uncovered as a confounding factor during preliminary behavioral studies. Fourth generation offspring were originally assessed in Barnes maze behavioral studies. Differences observed between D7 xenomitochondrial mice and C57BL/6NTac controls were attributed to partial 129S6 ancestry when control 129S6 and C57BL/6NTac mice showed substantial differences in performance (Cannon and Pinkert, unpublished data, 2011). This is in agreement with a previous report demonstrating that 129S6 mice performed poorly in certain tests compared to C57BL/6NTac mice [82]. Backcrossing of the D7 xenomitochondrial lineage to C57BL/6NTac males for a minimum of ten generations produced the required homogeneous nuclear background required for further phenotypic evaluation.

D7 xenomitochondrial mice were subjected to a battery of neuromuscular and motor assessments along with mitochondrial oxygen consumption and gene expression analyses. In some motor tests, D7 xenomitochondrial mice displayed slightly enhanced performance over wildtype mice. No differences were seen in oxygen consumption analysis. Gene expression studies in xenomitochondrial mice revealed changes in mtDNA transcription compared to wildtype controls. No changes in the expression of nuclear encoded respiratory complexes were observed, but changes were seen in several other nuclear encoded genes related to nuclear transcriptional regulation. These results indicate that mismatches occasioned by the presence of xenomitochondrial genomes led to compensatory transcriptional changes.

5. Conclusion

Using a variety of methods, a significant number of animal models of mitochondrial mutation were developed and described. These models provided insight into general mechanisms of mitochondrial physiology and dynamics and shed light on the processes by which diseases arise from mtDNA mutations including myopathic and neurologic changes. These efforts provide value to the research community; yet, the ultimate goal of creating in vivo models with specifically defined mtDNA sequence and heteroplasmy remains, as yet, unattained. To date, no animal model was reported in which a specific, human-disease based mtDNA mutation was recapitulated. The endeavors described above provide a foundation for continuing work that will eventually provide technologies to manipulate and precisely control mitochondrial genetics in animal models. Improved methods for modeling human mtDNA mutations in research animals will enable discerning studies of disease pathogenesis and the development of effective clinical therapies.

Highlights for Dunn et al., Animal models of human mitochondrial DNA mutations.

In vivo animal modeling of diseases resulting from human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutation are explored.

Animal models of mtDNA exchange or mutation were derived using a variety of strategies.

Novel transmitochondrial and xenomitochondrial founder mice and subsequent lineages reflect both heteroplasmic and homoplasmic mitochondrial mutations.

Genetically-modified mouse models provide tools for dissecting and understanding mitochondrial disorders and disease with specific utility for preclinical testing.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge K. Parameshwaran, F.F. Bartol, K. Steliou and I.A. Trounce. Mitochondrial studies in the Pinkert laboratory were supported by NIH, NSF, the MitoCure Foundation, the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station and Auburn University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG, de Bruijn MH, Coulson AR, Drouin J, Eperon IC, Nierlich DP, Roe BA, Sanger F, Schreier PH, Smith AJ, Staden R, Young IG. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290:457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez-Silva P, Enriquez JA, Montoya J. Replication and transcription of mammalian mitochondrial DNA. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:41–56. doi: 10.1113/eph8802514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taanman JW. The mitochondrial genome: structure, transcription, translation and replication. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1410:103–123. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutchison CA, 3rd, Newbold JE, Potter SS, Edgell MH. Maternal inheritance of mammalian mitochondrial DNA. Nature. 1974;251:536–538. doi: 10.1038/251536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz M, Vissing J. Paternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:576–580. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch M. Mutation accumulation in transfer RNAs: molecular evidence for Muller's ratchet in mitochondrial genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:209–220. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koyama H, Iwasa M, Ohtani S, Ohira H, Tsuchimochi T, Maeno Y, Isobe I, Matsumoto T, Yamada Y, Nagao M. Personal identification from human remains by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2002;23:272–276. doi: 10.1097/00000433-200209000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace DC, Brown MD, Lott MT. Mitochondrial DNA variation in human evolution and disease. Gene. 1999;238:211–230. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace DC. Mitochondria as chi, Genetics. 2008;179:727–735. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.91769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt IJ, Harding AE, Morgan-Hughes JA. Deletions of muscle mitochondrial DNA in patients with mitochondrial myopathies. Nature. 1988;331:717–719. doi: 10.1038/331717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace DC, Singh G, Lott MT, Hodge JA, Schurr TG, Lezza AM, Elsas LJ, 2nd, Nikoskelainen EK. Mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Science. 1988;242:1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.3201231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace DC, Zheng XX, Lott MT, Shoffner JM, Hodge JA, Kelley RI, Epstein CM, Hopkins LC. Familial mitochondrial encephalomyopathy (MERRF): genetic, pathophysiological, and biochemical characterization of a mitochondrial DNA disease. Cell. 1988;55:601–610. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudgson P, Bradley WG, Jenkison M. Familial "mitochondrial" myopathy. A myopathy associated with disordered oxidative metabolism in muscle fibres. 1. Clinical, electrophysiological and pathological findings. J Neurol Sci. 1972;16:343–370. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(72)90197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiz-Pesini E, Lott MT, Procaccio V, Poole JC, Brandon MC, Mishmar D, Yi C, Kreuziger J, Baldi P, Wallace DC. An enhanced MITOMAP with a global mtDNA mutational phylogeny. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D823–D828. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MITOMAP. Mitomap A Human Mitochondrial Genome Database. 2010 http://www.mitomap.org.

- 16.Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: A dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaefer AM, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM, Chinnery PF. The epidemiology of mitochondrial disorders--past, present and future. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1659:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berardo A, DiMauro S, Hirano M. A diagnostic algorithm for metabolic myopathies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:118–126. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0096-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finsterer J. Treatment of mitochondrial disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2010;14:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerr DS. Treatment of mitochondrial electron transport chain disorders: a review of clinical trials over the past decade. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace DC, Fan W. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial disease as modeled in the mouse. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1714–1736. doi: 10.1101/gad.1784909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruse SE, Watt WC, Marcinek DJ, Kapur RP, Schenkman KA, Palmiter RD. Mice with mitochondrial complex I deficiency develop a fatal encephalomyopathy. Cell Metab. 2008;7:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingraham CA, Burwell LS, Skalska J, Brookes PS, Howell RL, Sheu SS, Pinkert CA. NDUFS4: creation of a mouse model mimicking a Complex I disorder. Mitochondrion. 2009;9:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li K, Li Y, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Spencer E, Chen ZJ, Wang X, Williams RS. Cytochrome c deficiency causes embryonic lethality and attenuates stress-induced apoptosis. Cell. 2000;101:389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan SM, Smigrodzki RM, Swerdlow RH. Cell and animal models of mtDNA biology: progress and prospects. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C658–C669. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00224.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial diseases in man and mouse. Science. 1999;283:1482–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zsurka G, Kraytsberg Y, Kudina T, Kornblum C, Elger CE, Khrapko K, Kunz WS. Recombination of mitochondrial DNA in skeletal muscle of individuals with multiple mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy. Nat Genet. 2005;37:873–877. doi: 10.1038/ng1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinkert CA, Trounce IA. Production of transmitochondrial mice. Methods. 2002;26:348–357. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan W, Waymire KG, Narula N, Li P, Rocher C, Coskun PE, Vannan MA, Narula J, Macgregor GR, Wallace DC. A mouse model of mitochondrial disease reveals germline selection against severe mtDNA mutations. Science. 2008;319:958–962. doi: 10.1126/science.1147786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathews CE, McGraw RA, Berdanier CD. A point mutation in the mitochondrial DNA of diabetes-prone BHE/cdb rats. FASEB J. 1995;9:1638–1642. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.15.8529844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SB, Berdanier CD. Oligomycin sensitivity of mitochondrial F(1)F(0)-ATPase in diabetes-prone BHE/Cdb rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E702–E707. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.4.E702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li FY, Cuddon PA, Song J, Wood SL, Patterson JS, Shelton GD, Duncan ID. Canine spongiform leukoencephalomyelopathy is associated with a missense mutation in cytochrome b. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaderlund KH, Orvind E, Johnsson E, Matiasek K, Hahn CN, Malm S, Hedhammar A. A neurologic syndrome in Golden Retrievers presenting as a sensory ataxic neuropathy. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:1307–1315. doi: 10.1892/07-005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baranowska I, Jaderlund KH, Nennesmo I, Holmqvist E, Heidrich N, Larsson NG, Andersson G, Wagner EG, Hedhammar A, Wibom R, Andersson L. Sensory ataxic neuropathy in golden retriever dogs is caused by a deletion in the mitochondrial tRNATyr gene. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilmut I, Schnieke AE, McWhir J, Kind AJ, Campbell KH. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature. 1997;385:810–813. doi: 10.1038/385810a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans MJ, Gurer C, Loike JD, Wilmut I, Schnieke AE, Schon EA. Mitochondrial DNA genotypes in nuclear transfer-derived cloned sheep. Nat Genet. 1999;23:90–93. doi: 10.1038/12696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomez MC, Pope CE, Ricks DM, Lyons J, Dumas C, Dresser BL. Cloning endangered felids using heterospecific donor oocytes and interspecies embryo transfer. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2009;21:76–82. doi: 10.1071/rd08222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeda K, Kaneyama K, Tasai M, Akagi S, Takahashi S, Yonai M, Kojima T, Onishi A, Tagami T, Nirasawa K, Hanada H. Characterization of a donor mitochondrial DNA transmission bottleneck in nuclear transfer derived cow lineages. Mol Reprod Dev. 2008;75:759–765. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takeda K, Tasai M, Iwamoto M, Onishi A, Tagami T, Nirasawa K, Hanada H, Pinkert CA. Microinjection of cytoplasm or mitochondria derived from somatic cells affects parthenogenetic development of murine oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:1397–1404. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.036129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan Z-h, Zhou Y-y, Fu J, Jiao F, Zhao L-w, Guan P-f, Huang S-z, Zeng Y-t, Zeng F. Donor-host mitochondrial compatibility improves efficiency of bovine somatic cell nuclear transfer. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hochedlinger K, Jaenisch R. Nuclear transplantation, embryonic stem cells, and the potential for cell therapy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:275–286. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Timmis JN, Ayliffe MA, Huang CY, Martin W. Endosymbiotic gene transfer: organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrg1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grasso DG, Nero D, Law RH, Devenish RJ, Nagley P. The C-terminal positively charged region of subunit 8 of yeast mitochondrial ATP synthase is required for efficient assembly of this subunit into the membrane F0 sector. Eur J Biochem. 1991;199:203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zullo SJ. Gene therapy of mitochondrial DNA mutations: a brief, biased history of allotopic expression in mammalian cells. Semin Neurol. 2001;21:327–335. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DiMauro S, Mancuso M. Mitochondrial diseases: therapeutic approaches. Biosci Rep. 2007;27:125–137. doi: 10.1007/s10540-007-9041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Grey AD, Rae M. Ending Aging. The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs that could Reverse Human Aging in our Lifetime. New York: St. Martin's Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gearing DP, Nagley P. Yeast mitochondrial ATPase subunit 8, normally a mitochondrial gene product, expressed in vitro and imported back into the organelle. EMBO J. 1986;5:3651–3655. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manfredi G, Fu J, Ojaimi J, Sadlock JE, Kwong JQ, Guy J, Schon EA. Rescue of a deficiency in ATP synthesis by transfer of MTATP6, a mitochondrial DNA-encoded gene, to the nucleus. Nat Genet. 2002;30:394–399. doi: 10.1038/ng851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shidara Y, Yamagata K, Kanamori T, Nakano K, Kwong JQ, Manfredi G, Oda H, Ohta S. Positive contribution of pathogenic mutations in the mitochondrial genome to the promotion of cancer by prevention from apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1655–1663. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zullo SJ, Parks WT, Chloupkova M, Wei B, Weiner H, Fenton WA, Eisenstadt JM, Merril CR. Stable transformation of CHO Cells and human NARP cybrids confers oligomycin resistance (oli(r)) following transfer of a mitochondrial DNA-encoded oli(r) ATPase6 gene to the nuclear genome: a model system for mtDNA gene therapy. Rejuvenation Res. 2005;8:18–28. doi: 10.1089/rej.2005.8.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qi X, Sun L, Lewin AS, Hauswirth WW, Guy J. The mutant human ND4 subunit of complex I induces optic neuropathy in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1–10. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guy J, Qi X, Koilkonda RD, Arguello T, Chou TH, Ruggeri M, Porciatti V, Lewin AS, Hauswirth WW. Efficiency and safety of AAV-mediated gene delivery of the human ND4 complex I subunit in the mouse visual system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4205–4214. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ellouze S, Augustin S, Bouaita A, Bonnet C, Simonutti M, Forster V, Picaud S, Sahel JA, Corral-Debrinski M. Optimized allotopic expression of the human mitochondrial ND4 prevents blindness in a rat model of mitochondrial dysfunction. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:373–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lam BL, Feuer WJ, Abukhalil F, Porciatti V, Hauswirth WW, Guy J. Leber hereditary optic neuropathy gene therapy clinical trial recruitment: year 1. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1129–1135. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trifunovic A, Wredenberg A, Falkenberg M, Spelbrink JN, Rovio AT, Bruder CE, Bohlooly YM, Gidlof S, Oldfors A, Wibom R, Tornell J, Jacobs HT, Larsson NG. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature. 2004;429:417–423. doi: 10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kujoth GC, Hiona A, Pugh TD, Someya S, Panzer K, Wohlgemuth SE, Hofer T, Seo AY, Sullivan R, Jobling WA, Morrow JD, Van Remmen H, Sedivy JM, Yamasoba T, Tanokura M, Weindruch R, Leeuwenburgh C, Prolla TA. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005;309:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dai DF, Chen T, Wanagat J, Laflamme M, Marcinek DJ, Emond MJ, Ngo CP, Prolla TA, Rabinovitch PS. Age-dependent cardiomyopathy in mitochondrial mutator mice is attenuated by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Aging Cell. 2010;9:536–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kong YX, Van Bergen N, Trounce IA, Bui BV, Chrysostomou V, Waugh H, Vingrys A, Crowston JG. Increase in mitochondrial DNA mutations impairs retinal function and renders the retina vulnerable to injury. Aging Cell. 2011;10:572–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pinkert CA, Irwin MH, Johnson LW, Moffatt RJ. Mitochondria transfer into mouse ova by microinjection. Transgenic Res. 1997;6:379–383. doi: 10.1023/a:1018431316831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pogozelski WK, Fletcher LD, Cassar CA, Dunn DA, Trounce IA, Pinkert CA. The mitochondrial genome sequence of Mus terricolor: comparison with Mus musculus domesticus and implications for xenomitochondrial mouse modeling. Gene. 2008;418:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Irwin MH, Johnson LW, Pinkert CA. Isolation and microinjection of somatic cell-derived mitochondria and germline heteroplasmy in transmitochondrial mice. Transgenic Res. 1999;8:119–123. doi: 10.1023/a:1008925419758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Irwin MH, Parrino V, Pinkert CA. Construction of a mutated mtDNA genome and transfection into isolated mitochondria by electroporation. Adv Reprod. 2001;5:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 63.King MP, Attardi G. Human cells lacking mtDNA: repopulation with exogenous mitochondria by complementation. Science. 1989;246:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.2814477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cannon MV, Pinkert CA, Trounce I. Xenomitochondrial embryonic stem cells and mice: modeling human mitochondrial biology and disease. Gene Therapy Regulation. 2004;2:283–300. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bullough DA, Ceccarelli EA, Roise D, Allison WS. Inhibition of the bovine-heart mitochondrial F1-ATPase by cationic dyes and amphipathic peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;975:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(89)80346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levy SE, Waymire KG, Kim YL, MacGregor GR, Wallace DC. Transfer of chloramphenicol-resistant mitochondrial DNA into the chimeric mouse. Transgenic Res. 1999;8:137–145. doi: 10.1023/a:1008967412955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bunn CL, Wallace DC, Eisenstadt JM. Cytoplasmic inheritance of chloramphenicol resistance in mouse tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:1681–1685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.5.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trounce IA, Pinkert CA. Cybrid models of mtDNA disease and transmission, from cells to mice. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;77:157–183. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)77006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Swerdlow RH. Mitochondria in cybrids containing mtDNA from persons with mitochondriopathies. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:3416–3428. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marchington DR, Barlow D, Poulton J. Transmitochondrial mice carrying resistance to chloramphenicol on mitochondrial DNA: developing the first mouse model of mitochondrial DNA disease. Nat Med. 1999;5:957–960. doi: 10.1038/11403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sligh JE, Levy SE, Waymire KG, Allard P, Dillehay DL, Nusinowitz S, Heckenlively JR, MacGregor GR, Wallace DC. Maternal germ-line transmission of mutant mtDNAs from embryonic stem cell-derived chimeric mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14461–14466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250491597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Inoue K, Ito S, Takai D, Soejima A, Shisa H, LePecq JB, Segal-Bendirdjian E, Kagawa Y, Hayashi JI. Isolation of mitochondrial DNA-less mouse cell lines and their application for trapping mouse synaptosomal mitochondrial DNA with deletion mutations. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15510–15515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Inoue K, Nakada K, Ogura A, Isobe K, Goto Y, Nonaka I, Hayashi JI. Generation of mice with mitochondrial dysfunction by introducing mouse mtDNA carrying a deletion into zygotes. Nat Genet. 2000;26:176–181. doi: 10.1038/82826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kenyon L, Moraes CT. Expanding the functional human mitochondrial DNA database by the establishment of primate xenomitochondrial cybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9131–9135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barrientos A, Kenyon L, Moraes CT. Human xenomitochondrial cybrids. Cellular models of mitochondrial complex I deficiency. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14210–14217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McKenzie M, Trounce I. Expression of Rattus norvegicus mtDNA in Mus musculus cells results in multiple respiratory chain defects. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31514–31519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McKenzie M, Chiotis M, Pinkert CA, Trounce IA. Functional respiratory chain analyses in murid xenomitochondrial cybrids expose coevolutionary constraints of cytochrome b and nuclear subunits of complex III. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1117–1124. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McKenzie M, Trounce IA, Cassar CA, Pinkert CA. Production of homoplasmic xenomitochondrial mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1685–1690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303184101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pinkert CA, Trounce IA. Generation of transmitochondrial mice: development of xenomitochondrial mice to model neurodegenerative diseases. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;80:549–569. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)80027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trounce IA, McKenzie M, Cassar CA, Ingraham CA, Lerner CA, Dunn DA, Donegan CL, Takeda K, Pogozelski WK, Howell RL, Pinkert CA. Development and initial characterization of xenomitochondrial mice. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2004;36:421–427. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041778.84464.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cannon MV, Dunn DA, Irwin MH, Brooks AI, Bartol FF, Trounce IA, Pinkert CA. Xenomitochondrial mice: investigation into mitochondrial compensatory mechanisms. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crawley JN, Belknap JK, Collins A, Crabbe JC, Frankel W, Henderson N, Hitzemann RJ, Maxson SC, Miner LL, Silva AJ, Wehner JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Paylor R. Behavioral phenotypes of inbred mouse strains: implications and recommendations for molecular studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;132:107–124. doi: 10.1007/s002130050327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]