Abstract

Recently, the assumption of evolutionary continuity between humans and non-human primates has been used to bolster the hypothesis that human language is mediated especially by the ventral extreme capsule pathway that mediates auditory object recognition in macaques. Here, we argue for the importance of evolutionary divergence in understanding brain language evolution. We present new comparative data reinforcing our previous conclusion that the dorsal arcuate fasciculus pathway was more significantly modified than the ventral extreme capsule pathway in human evolution. Twenty-six adult human and twenty-six adult chimpanzees were imaged with diffusion-weighted MRI and probabilistic tractography was used to track and compare the dorsal and ventral language pathways. Based on these and other data, we argue that the arcuate fasciculus is likely to be the pathway most essential for higher-order aspects of human language such as syntax and lexical–semantics.

Keywords: language, evolution, brain, chimpanzee, arcuate fasciculus, extreme capsule

Introduction

Language is one of the fundamental evolutionary innovations of the human lineage. Our closest relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, can learn signs, but do not produce grammatical expressions (Wallman, 1992; Rivas, 2005; Premack, 2007). How did evolution transform a non-linguistic ancestral primate brain into a linguistic human brain? The fossil record provides few clues about this transformation: we know that brain volume increased dramatically (about threefold) after the human lineage separated from that leading to chimps and bonobos, about six to eight million years ago, but soft tissues like the brain are not preserved during fossilization, so there is no record of the changes in the brain’s internal organization related to language. To understand language evolution we must employ the comparative method, using information about the shared characteristics of living species to infer ancestral states (e.g., Sherwood et al., 2008; Preuss, 2011). In particular, we need to compare humans to the primates with which we are most closely related, namely apes and Old World monkeys, the latter including the familiar macaque monkeys. The scale of research done on the connections and functions of macaque brains makes them an especially valuable source of information.

Non-Human Primate Brain Communication Systems

Intuitively, uniquely human functions would seem to require uniquely human brain structures, so some neuroscientists have maintained that the classic language areas of Broca and Wernicke must be unique to humans (e.g., Brodmann, 1909; Crick and Jones, 1993). The work of evolution, however, more commonly involves the modification of existing anatomical structures to serve different functions than the addition of new structures. There is, in fact, considerable evidence that homologs of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas exist in apes and monkeys, based on similarities in architectonics, common position within the cortical mantle relative to other areas, and shared non-linguistic functions (e.g., Bonin, 1944; Galaburda and Pandya, 1982; Rizzolatti and Arbib, 1998; Preuss, 2000, 2011; Arbib, 2007). Yet, presumably, there was something about the non-human homologs of the classic language areas that made them suitable to be “recruited” (Bonin, 1944; Arbib, 2007) into the evolving language system.

Perhaps language evolved from brain systems that perform related functions in non-human primates, such as the production and perception of communicative calls and facial expressions. Area F5, the macaque homolog of the posterior part of Broca’s area (area 44), is involved in the production of orofacial expressions (Petrides et al., 2005), and mirror neurons in F5 respond to communicative mouth gestures, presumably using motor simulation to form a natural link between sender and receiver that facilitates communication (Rizzolatti and Fogassi, 2007). Calls and vocalizations are processed in the ventral auditory pathway that links anterior and middle STG, STS, and inferotemporal cortex (IT) with areas 45 and 47/12 (the likely homologs of the anterior and orbital parts of Broca’s area in humans) via the extreme capsule (Petrides and Pandya, 2009). This pathway is involved in auditory object identification. Although not specific for calls, both nodes (lateral belt area AL in temporal cortex and area 45 in ventrolateral PFC) include neurons that are highly responsive to species-specific vocalizations (Romanski et al., 1999). Functionally, area 45 may represent the referential meaning of calls, or may be involved in active controlled retrieval of memories associated with those calls stored in posterior cortical association areas (Petrides and Pandya, 2009). Additionally, the superior temporal gyrus appears to be left hemisphere dominant for discriminating species-specific vocalizations but not other types of auditory stimuli (Heffner and Heffner, 1986). Interestingly, in contrast to humans, in macaques the dominant prefrontal projection from posterior STG/STS is to dorsal prefrontal cortex (Petrides and Pandya, 2002), with only a minor projection to 44/45 (Deacon, 1992; Petrides and Pandya, 2009). This dorsal auditory “where” pathway carries information about the spatial location of sound (Romanski et al., 1999).

Although macaque area F5 is homologous to part of Broca’s area (area 44), which plays a critical role in speech production in humans, macaque F5 does not appear to mediate production of species-specific calls, given that lesions there do not disrupt calling (Aitken, 1981). Instead, macaque calls appear to be mediated by limbic and brainstem regions and are consequently largely involuntary symptoms of specific emotional and arousal states (Deacon, 1997).

Human Brain Language Systems and their Evolution

Evolutionary continuity

Did evolution build human language out of components of the non-human primate brain communication systems just described? If so, we would expect human language to also tap these systems. Broca’s area is obviously important for human expressive communication. In addition, the ventral auditory, or extreme capsule, pathway also exists in humans (Frey et al., 2008; Makris and Pandya, 2009), extending from pars orbitalis (47) and triangularis (45) to anterior STG and then back to angular gyrus. It has been reasonably proposed that this pathway, normally involved with retrieval of memories stored in posterior association cortex, was adapted during human evolution for controlled retrieval of verbal information in the human left hemisphere (Schmahmann et al., 2007; Makris and Pandya, 2009; Petrides and Pandya, 2009). However, comparative evidence suggests that, relative to the more dorsal arcuate fasciculus pathway, this ventral pathway was not a major locus of change in human evolution.

Evolutionary divergence

Although the human language system likely recruited components present in non-human primates, the key to understanding the evolution of human language lies not with the similarities to non-human primates but with the differences. That is, since humans possess language and other primates do not, there must be critical functional and anatomical differences between human and non-human primate brains that endow us with this special ability. We cannot determine the unique features of the human brain through human–macaque comparisons alone, as macaques are relatively distant evolutionary relatives of humans. Instead we must compare the human brain with that of our closest living relative, the chimpanzee. If we identify a characteristic in humans that is not present in chimpanzees or macaques, it is reasonable to assume that the trait uniquely evolved in humans after we diverged from chimpanzees six to eight million years ago.

Human brain language specializations

Given the traditionally accepted importance of Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas in language, were there changes in the temporal and frontal cortices that contain these regions? Here, we will focus on temporal cortex. Early functional MRI studies of the human visual system noted differences in the location of human and macaque visual areas (Ungerleider et al., 1998). Whereas macaque visual cortex spanned the lateral IT, human visual cortex was in a more ventral and posterior position. This prompted the suggestion that an evolutionary expansion of human language cortex in the lateral temporal lobe displaced human visual cortex to its present location. Although the visual system has not been mapped in the chimpanzee brain, the chimpanzee lunate sulcus, which marks the anterior border of V1, is in a macaque-like rather than a human-like location (Holloway et al., 2008), suggesting that chimpanzees largely preserve macaque-like visual cortical organization.

If human visual cortex was displaced by expanded temporal lobe language cortex, where specifically in the temporal lobe did this expansion take place? Lesion (Damasio et al., 1996; Dronkers et al., 2004), fMRI (Binder et al., 2009; Price, 2010), and structural and functional connectivity (Glasser and Rilling, 2008; Turken and Dronkers, 2011) data implicate the left MTG as a neural epicenter for lexical–semantic processing in the human brain (Turken and Dronkers, 2011). Functional MRI studies additionally implicate the adjacent STS as a core region involved in syntax (Grodzinsky and Friederici, 2006). If one assumes evolutionary continuity, one might reasonably hypothesize that this cortex (STS/MTG) is connected to ventrolateral prefrontal cortex via the ventral auditory pathway that was inherited from non-linguistic non-human primates. Further, this ventral pathway should mediate lexical–semantic retrieval and syntax. Given the expansion of cortical surface area (Van Essen and Dierker, 2007), we would also predict a corresponding expansion in the ventral extreme capsule pathway relative to the dorsal arcuate fasciculus pathway in linguistic humans vs. non-linguistic chimpanzees if the continuity hypothesis is correct. Furthermore, we might expect the pathway to be leftwardly asymmetric, given that lexical–semantics and syntax tend to be left-lateralized (Nucifora et al., 2005; Parker et al., 2005; Glasser and Rilling, 2008). We can test this prediction directly with comparative diffusion tractography (DT), which can estimate the extent and route of connections between cortical regions.

Results and Discussion

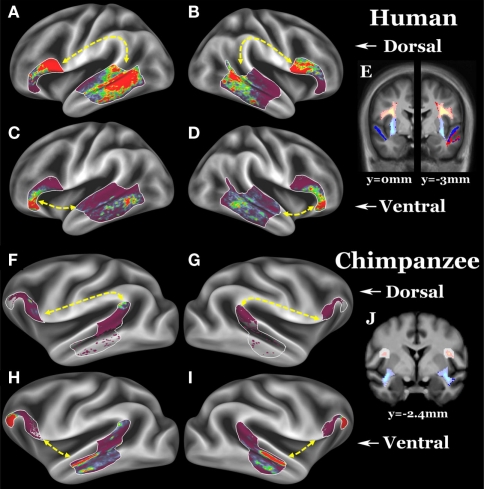

Contrary to the hypothesis that expanded temporal lobe language cortex is most strongly connected to Broca’s area via the ventral extreme capsule pathway, we previously found a qualitatively stronger connection via the dorsal arcuate fasciculus pathway (Rilling et al., 2008). These data suggest that the dorsal arcuate fasciculus pathway may have been the focus of language-related change in human evolution. To quantitatively evaluate this claim, we here compare a rough measure of connection strength of the dorsal and ventral pathways in a sample of 26 human brains with the homologous pathways in 26 chimpanzee brains. If the dorsal pathway was augmented in human evolution, then it should be stronger relative to the ventral pathway in humans vs. chimpanzees, and this is what was found. Although present in both hemispheres, the effect is more pronounced in the left hemisphere, where humans have a particularly strong dorsal pathway. Nevertheless, the dorsal pathway was leftwardly asymmetric in both species, a finding consistent with previously reported leftward asymmetries in the planum temporale, a portion of Wernicke’s area (Gannon et al., 1998; Hopkins et al., 1998, 2008), and in peri-sylvian white matter volume (Cantalupo et al., 2009). These findings suggest that the anatomical substrates for lateralization of communicative functions may have been present in the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees (Cantalupo et al., 2009). In contrast to the dorsal pathway, the ventral pathway is not asymmetric in either humans or chimpanzees. We would expect a pathway that mediates syntax and lexical–semantic retrieval to be leftwardly asymmetric, like the human arcuate, rather than symmetric, like the human extreme capsule (Table 1; Figure 1).

Table 1.

Diffusion tractography normalized streamline counts and asymmetry indices (AIs) in chimpanzees and humans.

| Left dorsal | Right dorsal | Left ventral | Right ventral | Left D/V AI | Right D/V AI | Dorsal L/R AI | Ventral L/R AI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 116073 | 53214 | 27947 | 34753 | 0.61 ± 0.06** | 0.00 ± 0.13 | 0.42 ± 0.11** | −0.17 ± 0.09 |

| Chimpanzee | 2865 | 379 | 23761 | 18942 | −0.84 ± 0.08** | −0.88 ± 0.08** | 0.66 ± 0.07** | 0.08 ± 0.10 |

| Human–Chimpanzee | 1.44 ± 0.10** | 0.89 ± 0.15** | −0.24 ± 0.13 | −0.24 ± 0.13 |

Streamline counts were normalized to remove variance in ROI size (after deformation from standard ROIs to individuals) and for differences in trackability across subjects within a species. The assumption was made that the total number of streamlines counted across all four pathways should be the same across individuals within a species, as we are only interested in relative differences between the pathways across subjects and want the average normalized streamline counts to reflect equal contributions from all subjects. D, dorsal, V, ventral, L, Left, R, right, AI, Asymmetry Index [AILR = (WL − WR)/(WL + WR) or AIDV = (WD − WV)/(WD + WV)], * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01.

Figure 1.

(A–D) Group average left dorsal, right dorsal, left ventral, and right ventral pathways of 26 humans. (E) Left (y = −3 mm) and right (y = 0 mm) dorsal and ventral pathways in coronal slices; dorsal pathway is yellow–red, ventral pathway is light blue–blue. (F–I) Group average left dorsal, right dorsal, left ventral, and right ventral pathways of 26 chimpanzees. (J) Left and right (both y = −2.4 mm) dorsal and ventral pathways in coronal slices. Surface ROIs are displayed as white outlines. Fascicle selection ROIs are displayed as a translucent white layer over the pathways. For surface results, the scale is 0 (clear) to 30 (red) streamlines, for the volume results, the scale is 5 (clear) to 300 (yellow or light blue) streamlines.

Finally, as reported previously (Rilling et al., 2008), in humans the arcuate projections into the temporal cortex are concentrated in STS and MTG, ventral to classic Wernicke’s area, whereas in chimpanzees they are concentrated in STG. On the other hand, extreme capsule projections to temporal cortex are concentrated in STS and cortex ventral to it in both species. Thus, in terms of both pathway strength and pattern of cortical connectivity, the dorsal arcuate fasciculus seems to have undergone more evolutionary change than the ventral extreme capsule pathway.

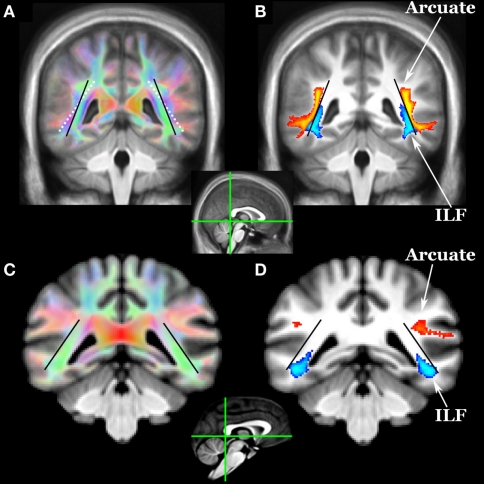

Did the expanded arcuate fasciculus pathway displace the ventral visual stream in the human brain, as suggested above? Tracking the ventral visual stream (the inferior longitudinal fasciculus, ILF) in both species revealed that the arcuate abuts the ILF in humans but not chimps and does appear to have displaced ILF in a ventromedial direction (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Location of arcuate (yellow–orange) and inferior longitudinal fasciculi (ILF, blue) in (A,B) humans and (C,D) chimpanzees as revealed by diffusion tractography. Coronal sections for each species are at the posterior aspect of the splenium (see mid-sagittal insets). Tracts include voxels in which 33% or more subjects have a pathway above threshold (0.1% of waytotal). The black lines indicate the angle of the ILF in humans and chimpanzees. The white dotted line in (A) shows the angle of the ILF of chimps overlaid on the human color FA map. In humans, the arcuate appears to have displaced the ILF in a ventromedial direction.

Conclusion

Comparative DT data suggest that the specialized, derived features of human language (syntax and lexical–semantics) are likely to be mediated by the arcuate fasciculus pathway. The most cited evidence to the contrary is from a paper by Saur et al. (2010) who used fMRI to identify frontal and temporal cortical regions involved in processing word meaning and then used DT to track between these functional ROIs. They found stronger connectivity between frontal and temporal semantic ROIs via the ventral extreme capsule pathway as opposed to the dorsal arcuate fasciculus pathway. Critically, however, despite widespread activation across the MTG, they limited their tractography seeds to activation peaks in the anterior and posterior extremes of the MTG. That is, they did not track from the core lexical–semantic and syntactical areas in mid MTG and STS respectively (Vigneau et al., 2006; Glasser and Rilling, 2008; Turken and Dronkers, 2011). Furthermore, they used tensor-based single fiber tractography, which is unable to follow non-dominant pathways and gives less accurate estimates of fiber orientations (Behrens et al., 2007). Here we show that tracking from mid MTG/STS with crossing-fiber tractography yields stronger connectivity via a dorsal compared with a ventral route. This is not to say that the extreme capsule pathway has no role in human language. Indeed, there is evidence that electrical stimulation of the extreme/external capsule (EC) induces semantic paraphasias (Martino et al., 2010). Other pathways such as the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF) may also be involved (Duffau, 2008; Turken and Dronkers, 2011). However, we argue that the most significant modification of human brain connectivity related to language evolution, in particular the development of lexical–semantic retrieval and syntax, occurred in the arcuate fasciculus.

Materials and Methods

Subjects, acquisition, and preprocessing

Twenty-six humans (17 males, mean age = 20.0, SD = 1.2) and 26 chimpanzees (26 female, mean age = 29.4, SD = 13.0) were scanned with anatomical and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) on Siemens 3T Trio scanners. All chimpanzee and human procedures were approved by the Emory University Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Review Board, respectively. Informed consent was obtained from all human subjects. The DWIs were matched across species in diffusion directions (60 b = 1000, 6 b = 0). Given their smaller brain size, chimpanzees were scanned at higher spatial resolution (1.8 vs. 2 mm isotropic for humans) and with more averages (8 vs. 2) to compensate for lower SNR. EPI distortion in chimpanzees was reduced by using a reduced FOV and matrix along the phase encoding direction to reduce the number of phase encoding steps and shorten the echo train. Following motion and eddy current correction, remaining EPI distortion was corrected using an improved version of the method of (Andersson et al., 2003). Up to three fiber orientations were estimated in each voxel using BEDPOSTx (Behrens et al., 2007). T1-weighted (T1w) anatomical images were acquired from both humans and chimpanzees with TR/TE/TI = 2600/900/3 ms and flip angle of 8°. Chimpanzees were again scanned with higher resolution (0.8 vs. 1 mm isotropic) and more averages (2 vs. 1). Additionally a single T2w average was acquired in chimpanzees at 0.8 mm resolution with otherwise identical parameters to previous human scans (Glasser and Van Essen, 2011). T1w image volume and surface processing has been previously described in humans (Glasser and Van Essen, 2011), and surfaces were made using FreeSurfer 5.1. Obtaining maximally accurate FreeSurfer surfaces in chimpanzees requires several steps outside of FreeSurfer: bias field removal, brain extraction, linear alignment to the FreeSurfer template, and changing image dimensions to 1 mm to avoid automatic resampling. The chimpanzees had a significant bias field, requiring special estimation. As the 3T T1w and T2w images have similar bias fields and inverted contrast (Glasser and Van Essen, 2011), we estimated the bias field using the approximation in Equation 1, where x and 1/x are the contrast for myelin in the T1w and T2w images respectively, and b is the bias field.

| (1) |

When restricted to brain tissue, lowpass filtering “b” produces an accurate bias field estimate. A non-linear volumetric chimpanzee template was previously generated (Li et al., 2010) and we iteratively generated a chimpanzee surface template with standard energy-based FreeSurfer registration. Chimpanzee myelin maps were generated using methods described previously in humans (Glasser and Van Essen, 2011) and human myelin maps were from that study.

Tractography methods

Our goal was to track between Broca’s region (i.e., area 44, 45, and 47l) and association cortex in the posterior two-thirds of the lateral temporal cortex lying dorsal and anterior to visual association cortex and ventral to early auditory cortex. Frontal and temporal surface ROIs (white outlines in Figures 1A–D, G–I) were used together with volumetric fascicle selection ROIs (translucent white on coronal slice in Figures 1E,J) that required streamlines to travel via either a dorsal or ventral route. ROIs were drawn on group average templates and then warped into individual subjects’ diffusion space for tractography.

Surface ROIs were defined as follows: Fiber pathways of interest were initially localized by tracking from white matter ROIs in the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) and EC. The surface terminations from this tractography defined an outer bound on the possible connections between frontal and temporal regions, and, within this area, myelin maps and probabilistic cytoarchitecture were used to define homologous frontal and temporal surface ROIs across hemispheres and species. The frontal surface ROI was defined in humans using surface-based probabilistic cytoarchitectonic areas 44, 45, and 47l (Amunts et al., 1999; Öngür et al., 2003; Fischl et al., 2008; Van Essen et al., 2011) and was located in a region of lightly myelinated cortex posterior/superior to heavily myelinated area 47 m on the inferior frontal gyrus. In chimpanzees, volume-based probabilistic areas 44 and 45 (Schenker et al., 2010) together with cortical myelination were used to define a homologous region. Single ROI tractography from this region was used in both species to further refine the localization of temporal terminations. The lightly myelinated posterior two-thirds of the lateral temporal cortex in the STG, STS, and MTG including probabilistic areas TE 3.0 (Morosan et al., 2005) in humans and 22 (Spocter et al., 2010) in chimps that was bordered superiorly by more myelinated auditory belt cortex, posteriorly by more myelinated MT+ cortex, and ventrally by more myelinated ventral visual cortex formed the temporal surface ROI. These ROIs were constrained to include only those vertices that also received surface terminations in the localizer tractography.

The resulting surface ROIs were largely the same shape and size across hemispheres, but differed across species. As has been previously suspected for macaque monkeys (Ungerleider et al., 1998; Van Essen and Dierker, 2007), temporal cortical areas have undergone significant shifts relative to the cortical geography in humans relative to chimpanzees (Glasser et al., 2011), and geographically corresponding ROIs (i.e., ROIs of the same shape and size) would not have spanned homologous cortex. The availability of human and chimpanzee surface templates with rich probabilistic post-mortem and in vivo architectonic data is unprecedented for a non-invasive connectivity study.

The final probabilistic tractography was constrained to run symmetrically via either the dorsal or ventral route between the surface ROIs and streamlines were displayed on the surface (terminations) and in the volume (fascicles). 150,000 streamlines were sent out from each vertex/voxel in proportion to the fiber volume fraction in voxels with more than one fiber modeled and streamlines were stopped when they attempted to exit the white matter surface. The total number of streamlines that successfully traced the required route (the “waytotal”) was recorded during tractography. Within a subject, these waytotals are proportional to the probability that the streamlines reach their target ROIs, and provide a rough metric of pathway strength when compared to another pathway seeded from ROIs of the same size. To compare across individuals, however, it is necessary to normalize these waytotals by the size of the ROIs used as seeds and the total number of streamlines counted across all four pathways. This normalization accounts for differences in ROI size after deforming standard ROIs to individuals and for global differences in trackability between individuals (e.g., motion, SNR, brain size) within a species. AIs were used (see Table 1 for values and definitions), and the surface terminations and volume probabilistic fascicles were also normalized by the sum of each subject’s waytotals so each contributed equally to the group average (Figure 1). A one-sample t-test (two tailed) was used to test if each AI was significantly different from zero (no asymmetry), and a two-sample t-test (two tailed) was used to test if the AIs were different between humans and chimpanzees.

The ILF (Figure 2) was defined using two volume ROIs orthogonal to the pathway one-third of the way back from the temporal pole and in the deep occipital white matter. The atlas brain was rotated 45° around the x-axis so that a coronal section cut the ILF orthogonally in the anterior temporal lobe. An ROI was drawn within the entire white matter on this slice, and single ROI tractography was done to identify occipital projections. A second ROI was drawn to select these projections, and the result in Figure 2 was produced with symmetric two ROI tractography between these ROIs.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ashley DeMarco, Longchuan Li, Govind Bhagavatheeshwaran, Bhargav Errangi, Xiaodong Zhang, and Xiaoping Hu for assistance with various aspects of this study. Matthew F. Glasser was supported by a National Research Science Award – Medical Scientist NIH T32 GM007200. Mark Jenkinson provided a preview version of boundary-based registration in FLIRT for T2w to T1w registration. Bill Hopkins provided probabilistic cytoarchitectonic areas for the chimpanzees. Some computations were performed using facilities of the Washington University Center for High Performance Computing, partially supported by Grant NCRR 1S10RR022984-01. Funding was provided by NIMH Grant R01 MH084068-01A1, NIA Grant 5P01 AG026423-03, and the Yerkes Base Grant: NIH RR-00165. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- Aitken P. G. (1981). Cortical control of conditioned and spontaneous vocal behavior in rhesus monkeys. Brain Lang. 13, 171–184 10.1016/0093-934X(81)90137-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K., Schleicher A., Bürgel U., Mohlberg H., Uylings H., Zilles K. (1999). Broca’s region revisited: cytoarchitecture and intersubject variability. J. Comp. Neurol. 412, 319–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J. L. R., Skare S., Ashburner J. (2003). How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 20, 870–888 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00336-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbib M. A. (2007). “Premotor cortex and the mirror neuron hypothesis for the evolution of language,” in Evolution of Nervous Systems, Vol. 4, Primates, eds Kaas J. H., Preuss T. M. (Oxford: Elsevier; ), 417–422 [Google Scholar]

- Behrens T., Berg H. J., Jbabdi S., Rushworth M., Woolrich M. (2007). Probabilistic diffusion tractography with multiple fibre orientations: what can we gain? Neuroimage 34, 144–155 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder J. R., Desai R. H., Graves W. W., Conant L. L. (2009). Where is the semantic system? A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies. Cereb. Cortex 19, 2767–2796 10.1093/cercor/bhp055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin G. V. (1944). “The architecture,” in The Precentral Motor Cortex, ed. Bucy P. C. (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press; ), 7–82 [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K. (1909). Vergleichende Lokalisationslehre der Grosshirnrhinde. Leipzig: Barth (reprinted as Brodmann’s “Localisation in the Cerebral Cortex,” translated and edited by Garey L. J. London: Smith-Gordon, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- Cantalupo C., Oliver J., Smith J., Nir T., Taglialatela J. P., Hopkins W. D. (2009). The chimpanzee brain shows human-like perisylvian asymmetries in white matter. Eur. J. Neurosci. 30, 431–438 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06830.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F., Jones E. (1993). Backwardness of human neuroanatomy. Nature 361, 109–110 10.1038/361109a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio H., Grabowski T. J., Tranel D., Hichwa R. D., Damasio A. R. (1996). A neural basis for lexical retrieval. Nature 380, 499–505 10.1038/380499a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon T. (1997). The Symbolic Species. New York: W. W. Norton [Google Scholar]

- Deacon T. W. (1992). Cortical connections of the inferior arcuate sulcus cortex in the macaque brain. Brain Res. 573, 8–26 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90109-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dronkers N. F., Wilkins D. P., Van Valin R. D., Jr., Redfern B. B., Jaeger J. J. (2004). Lesion analysis of the brain areas involved in language comprehension. Cognition 92, 145–177 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffau H. (2008). The anatomo-functional connectivity of language revisited. New insights provided by electrostimulation and tractography. Neuropsychologia 46, 927–934 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B., Rajendran N., Busa E., Augustinack J., Hinds O., Yeo B., Mohlberg H., Amunts K., Zilles K. (2008). Cortical folding patterns and predicting cytoarchitecture. Cereb. Cortex 18, 1973. 10.1093/cercor/bhm225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey S., Campbell J. S., Pike G. B., Petrides M. (2008). Dissociating the human language pathways with high angular resolution diffusion fiber tractography. J. Neurosci. 28, 11435–11444 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2388-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda A. M., Pandya P. N. (1982). “Role of architectonics and connections in the study of primate brain evolution,” in Primate Brain Evolution: Methods and Concepts, eds Armstrong E., Falk D. (New York: Plenum; ), 203–226 [Google Scholar]

- Gannon P. J., Holloway R. L., Broadfield D. C., Braun A. R. (1998). Asymmetry of chimpanzee planum temporale: humanlike pattern of Wernicke’s brain language area homolog. Science 279, 220–222 10.1126/science.279.5348.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser M., Preuss T., Snyder L., Nair G., Rilling J., Zhang X., Li L., Van Essen D. (2011). Comparative Mapping of Cortical Myelin Content in Humans, Chimpanzees, and Macaques Using T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience [Google Scholar]

- Glasser M. F., Rilling J. K. (2008). DTI tractography of the human brain’s language pathways. Cereb. Cortex 18, 2471–2482 10.1093/cercor/bhn011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser M. F., Van Essen D. C. (2011). Mapping human cortical areas in ivo based on myelin content as revealed by T1- and T2-weighted MRI. J. Neurosci. 31, 11597–11616 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2180-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinsky Y., Friederici A. D. (2006). Neuroimaging of syntax and syntactic processing. Curr Opin Neurobiol 16, 240–246 10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner H. E., Heffner R. S. (1986). Effect of unilateral and bilateral auditory cortex lesions on the discrimination of vocalizations by Japanese macaques. J. Neurophysiol. 56, 683–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway R. L., Sherwood C. C., Rilling J. K., Hof P. R. (2008). “Evolution, of the brain: in humans – paleoneurology,” in Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, eds Binder M. D., Hirokawa N., Windhorst U., Hirsch M. C. (Springer-Verlag; ), 1326–1334 [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins W. D., Marino L., Rilling J. K., Macgregor L. A. (1998). Planum temporale asymmetries in great apes as revealed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Neuroreport 9, 2913–2918 10.1097/00001756-199808240-00043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins W. D., Taglialatela J. P., Meguerditchian A., Nir T., Schenker N. M., Sherwood C. C. (2008). Gray matter asymmetries in chimpanzees as revealed by voxel-based morphometry. Neuroimage 42, 491–497 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Preuss T. M., Rilling J. K., Hopkins W. D., Glasser M. F., Kumar B., Nana R., Zhang X., Hu X. (2010). Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) precentral corticospinal system asymmetry and handedness: a diffusion magnetic resonance imaging study. PloS ONE 5, e12886. 10.1371/journal.pone.0012886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N., Pandya D. N. (2009). The extreme capsule in humans and rethinking of the language circuitry. Brain Struct. Funct. 213, 343–358 10.1007/s00429-008-0199-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino J., Brogna C., Robles S. G., Vergani F., Duffau H. (2010). Anatomic dissection of the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus revisited in the lights of brain stimulation data. Cortex 46, 691–699 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morosan P., Schleicher A., Amunts K., Zilles K. (2005). Multimodal architectonic mapping of human superior temporal gyrus. Anat. Embryol. (Berl). 210, 401–406 10.1007/s00429-005-0029-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nucifora P. G., Verma R., Melhem E. R., Gur R. E., Gur R. C. (2005). Leftward asymmetry in relative fiber density of the arcuate fasciculus. Neuroreport 16, 791–794 10.1097/00001756-200505310-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öngür D., Ferry A., Price J. (2003). Architectonic subdivision of the human orbital and medial prefrontal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 460, 425–449 10.1002/cne.10609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. J., Luzzi S., Alexander D. C., Wheeler-Kingshott C. A., Ciccarelli O., Lambon Ralph M. A. (2005). Lateralization of ventral and dorsal auditory-language pathways in the human brain. Neuroimage 24, 656–666 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M., Cadoret G., Mackey S. (2005). Orofacial somatomotor responses in the macaque monkey homologue of Broca’s area. Nature 435, 1235–1238 10.1038/nature03628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M., Pandya D. N. (2002). “Association pathways of the prefrontal cortex and functional observations,” in Principles of Frontal Lobe Function, eds Stuss D. T., Knight R. T. (New York: Oxford University Press; ), 31–50 [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M., Pandya D. N. (2009). Distinct parietal and temporal pathways to the homologues of Broca’s area in the monkey. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000170. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premack D. (2007). Human and animal cognition: continuity and discontinuity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13861–13867 10.1073/pnas.0706147104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss T. M. (2000). “What’s human about the human brain?” in The New Cognitive Neurosciences, 2nd Edn, ed. Michael S. Gazzaniga (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; ), 1219–1234 [Google Scholar]

- Preuss T. M. (2011). The human brain: rewired and running hot. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1225(Suppl. 1), E182–E191 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06001.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price C. J. (2010). The anatomy of language: a review of 100 fMRI studies published in 2009. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1191, 62–88 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05444.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rilling J. K., Glasser M. F., Preuss T. M., Ma X., Zhao T., Hu X., Behrens T. E. (2008). The evolution of the arcuate fasciculus revealed with comparative DTI. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 426–428 10.1038/nn2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas E. (2005). Recent use of signs by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in interactions with humans. J. Comp. Psychol. 119, 404–417 10.1037/0735-7036.119.4.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G., Arbib M. A. (1998). Language within our grasp. Trends Neurosci. 21, 188–194 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01260-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G., Fogassi L. (2007). “Mirror neurons and social cognition,” in The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, eds Dunbar R. I. M., Barrett L. (Oxford: Oxford University Press; ), 179–196 [Google Scholar]

- Romanski L. M., Tian B., Fritz J., Mishkin M., Goldman-Rakic P. S., Rauschecker J. P. (1999). Dual streams of auditory afferents target multiple domains in the primate prefrontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 1131–1136 10.1038/16056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saur D., Schelter B., Schnell S., Kratochvil D., Kupper H., Kellmeyer P., Kummerer D., Kloppel S., Glauche V., Lange R., Mader W., Feess D., Timmer J., Weiller C. (2010). Combining functional and anatomical connectivity reveals brain networks for auditory language comprehension. Neuroimage 49, 3187–3197 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker N. M., Hopkins W. D., Spocter M. A., Garrison A. R., Stimpson C. D., Erwin J. M., Hof P. R., Sherwood C. C. (2010). Broca’s area homologue in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): probabilistic mapping, asymmetry, and comparison to humans. Cereb. Cortex 20, 730. 10.1093/cercor/bhp138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann J. D., Pandya D. N., Wang R., Dai G., D’Arceuil H. E., De Crespigny A. J., Wedeen V. J. (2007). Association fibre pathways of the brain: parallel observations from diffusion spectrum imaging and autoradiography. Brain 130, 630–653 10.1093/brain/awl359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood C. C., Subiaul F., Zawidzki T. W. (2008). A natural history of the human mind: tracing evolutionary changes in brain and cognition. J. Anat. 212, 426–454 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00868.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spocter M. A., Hopkins W. D., Garrison A. R., Bauernfeind A. L., Stimpson C. D., Hof P. R., Sherwood C. C. (2010). Wernicke’s area homologue in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and its relation to the appearance of modern human language. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 277, 2165. 10.1098/rspb.2010.0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turken A. U., Dronkers N. F. (2011). The neural architecture of the language comprehension network: converging evidence from lesion and connectivity analyses. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 5:1. 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider L. G., Courtney S. M., Haxby J. V. (1998). A neural system for human visual working memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 883–890 10.1073/pnas.95.3.883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen D. C., Glasser M. F., Dierker D. L., Harwell J., Coalson T. (2011). Parcellations and hemispheric asymmetries of human cerebral cortex analyzed on surface-based atlases. Cereb. Cortex. 10.1093/cercor/bhr291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen D. C., Dierker D. L. (2007). Surface-based and probabilistic atlases of primate cerebral cortex. Neuron 56, 209–225 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneau M., Beaucousin V., Herve P. Y., Duffau H., Crivello F., Houde O., Mazoyer B., Tzourio-Mazoyer N. (2006). Meta-analyzing left hemisphere language areas: phonology, semantics, and sentence processing. Neuroimage 30, 1414–1432 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallman J. (1992). Aping Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]