Abstract

Objective

To determine whether asthma-specific quality of life during pregnancy is related to asthma exacerbations and to perinatal outcomes.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial of inhaled beclomethasone versus theophylline in the treatment of moderate asthma during pregnancy. The Juniper Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) was administered to patients at enrollment. Exacerbations were defined as asthma symptoms requiring a hospitalization, unscheduled medical visit, or oral corticosteroid course.

Results

Quality of life assessments were provided by 310 of the 385 participants who completed the study. There was more than a 25% decrease in the odds of a subsequent asthma exacerbation for every 1-point increase in AQLQ score for the overall score (odds ratio [OR] 0.73, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.55–0.96), emotion domain (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.59–0.88), and symptoms domain (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.57–0.94). These relationships were not significantly influenced by initial symptom frequency or forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1). No significant relationships were demonstrated between enrollment AQLQ scores and preeclampsia, preterm birth, low birth weight, or small for gestational age.

Conclusion

Asthma-specific quality of life in early pregnancy is related to subsequent asthma morbidity during pregnancy but not to perinatal outcomes.

Keywords: asthma, exacerbations, perinatal outcomes, pulmonary function, quality of life

Introduction

Asthma is the most common of all potentially serious medical problems that complicate pregnancy (1). We recently reported the results of a large prospective multicenter observational study, noting 20.7% of pregnant asthmatic patients experienced an asthma exacerbation requiring oral corticosteroids with or without a hospitalization or other unscheduled visit (2). Asthma severity in the same study, based on symptoms and pulmonary function, predicted the frequency of subsequent asthma exacerbations during pregnancy (2).

Studies on the effect of maternal asthma on perinatal outcomes have produced conflicting data (3, 4), which may relate in part to differences in the degrees of severity and/or control in the asthmatic populations surveyed. The authors in one study concluded that women with daily asthma symptoms are at increased risk of delivering small for gestational age (SGA) infants (5) and developing preeclampsia (6), and we have previously reported a relationship between decreased pulmonary function in asthmatic pregnant women and increased risks of preeclampsia and preterm birth (7).

Questionnaires that assess asthma-specific quality of life were introduced in 1992 (8). Asthma-specific quality of life reflects more aspects of the subjective asthma experience than symptoms alone (9) and has also been shown to be a separate factor from pulmonary function (10). It is therefore possible that asthma-specific quality of life would be a more sensitive reflection of asthma impairment, impact, and risk during pregnancy than symptoms and pulmonary function. However, we were unable to locate any prior studies that have examined asthma-specific quality of life during pregnancy. Therefore, this analysis was designed to evaluate the relationship between asthma-specific quality of life in early pregnancy and subsequent asthma and perinatal morbidity.

Methods

Patients

This was a secondary analysis of data from a prospective, randomized, double-blind, double-placebo controlled trial of inhaled beclomethasone versus theophylline in the treatment of mild-moderate persistent asthma during pregnancy conducted at 13 centers of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (11). Patients with physician-diagnosed asthma who met the protocol criteria for mild-moderate persistent severity were randomized to receive either inhaled beclomethasone (504 μg/day) or theophylline 200 to 400 mg twice a day (bid) (based on theophylline level). Informed written consent was obtained for all participants, and the study was approved by each institution's local Institutional Review Board.

Asthma Measures

The standardized version of the Juniper Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) (12) was administered to patients at enrollment (<26 weeks' gestation). The AQLQ contains 32 items in four domains (specific functional areas of concern): symptoms (12 questions), activities (11 questions), emotional function (5 questions), and environmental exposure (4 questions). Patients respond to each question based on their experiences during the previous 2 weeks. Item responses contain a 7-point Likert scale that ranges from a score of 1 (worst) to 7 (best). Domains scores are calculated as the mean score of the items in that domain, and the overall score is the mean of all 32 AQLQ items. Spirometry (>4 h after bronchodilator) and self-reported number of days with asthma symptoms in the past 4 weeks were also obtained on enrollment.

Outcome Measures

Asthma exacerbations were defined as asthma symptoms requiring a hospitalization, other unscheduled medical visit, or oral corticosteroid course. Perinatal outcomes assessed included preeclampsia (hypertension plus proteinuria), preterm birth (<37 weeks), low birth weight (<2500 g), and SGA (<10% birth weight for gestational age).

Data Analysis

Hypothesis testing for two-sample comparisons was conducted with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Adjusted analyses were performed using the logistic regression to determine whether or not relationships between asthma-specific quality life and outcomes were independent of symptom and pulmonary function measurements. The dependent variables in these analyses were the outcomes as yes/no variables. Two-tailed statistical tests were used, and the nominal statistical significance was set at p < .05. No correction was made for multiple comparisons.

Results

Quality of life assessments were provided by 310 of 385 participants who completed the study. The mean age of participants was 23.5 ± 5.7 years. Most (61.6%) were African American (61.6%) and received government-assisted medical insurance (84.8%). 16.5% reported smoking at least one cigarette per day in the week before enrollment. The mean gestational age of participants at enrollment was 20.5 ± 4.5 weeks. Exacerbations after enrollment occurred in 20.7% of these patients; preeclampsia in 7.7%; preterm birth in 11.9%; low birth weight in 9.0%; and SGA in 6.5%.

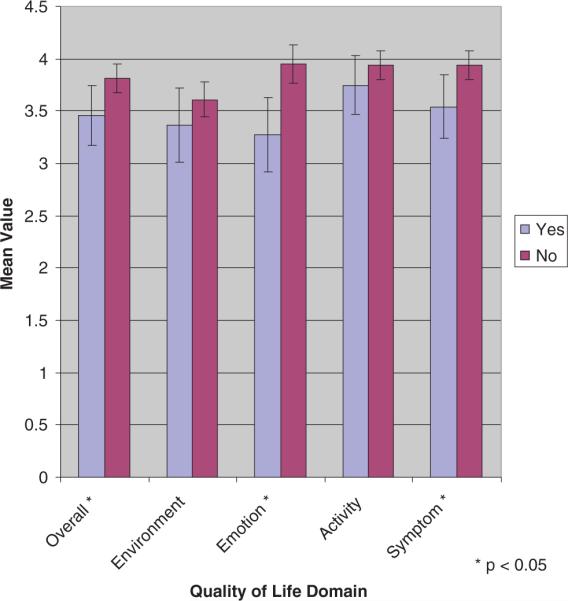

There were no significant differences in baseline quality of life and perinatal outcomes between the two study groups (Table 1). Initial overall quality of life was significantly lower (p = .047) in women who experienced subsequent exacerbations (mean 3.5) compared to women who did not experienced exacerbations (mean 3.8) (Figure 1). The differences were most pronounced in the emotion domain (mean 3.3 versus 3.9; p = .003), and were also significant in the symptoms domain (mean 3.5 versus 3.9; p=.032) (Figure 1). There was more than a 25% decrease in the odds of a subsequent exacerbation for every 1-point increase in AQLQ score for the overall score (odds ratio [OR] 0.73, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.55–0.96), emotion domain (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.59–0.88), and symptoms domain (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.57–0.94). The relationships between asthma exacerbations and overall quality of life as well as emotion and symptoms domains were not significantly influenced by initial symptom frequency or forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Baseline quality of life and outcomes of study patients*.

| Characteristic | Total sample (N = 310) | Beclomethasone (N = 153) | Theophylline (N = 157) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life: (mean [SD]) | |||

| Overall | 3.74(1.07) | 3.71(1.06) | 3.77(1.08) |

| Symptoms | 3.86(1.14) | 3.83(1.17) | 3.88(1.13) |

| Activity | 3.90(1.04) | 3.84(1.02) | 3.95(1.06) |

| Emotions | 3.81(1.47) | 3.76(1.42) | 3.85(1.52) |

| Environment | 3.56(1.35) | 3.55(1.36) | 3.57(1.34) |

| Exacerbations | 20.7% | 19.6% | 21.7% |

| Hospitalizations | 7.4% | 6.5% | 8.3% |

| Other unscheduled visits | 19.0% | 17.0% | 21.0% |

| Oral steroids | 11.9% | 10.5% | 13.4% |

| Preeclampsia | 7.7% | 7.8% | 7.6% |

| Preterm birth < 37 weeks | 11.9% | 13.7% | 10.2% |

| Low birth weight < 2500 g | 9.0% | 9.2% | 8.9% |

| Small for gestational age | 6.5% | 6.5% | 6.4% |

No significant differences between groups.

Figure 1.

Mean overall and specific domain (environment, emotion, activity, symptom) quality of life scores for patients with (yes) and without (no) exacerbations. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

TABLE 2.

Relationship of asthma-specific quality of life (overall and emotion and symptom domains) to asthma exacerbations, adjusted for initial symptom frequency and FEV1*

| Odds ratio† (95% confidence interval), p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjustment | Overall | Emotion | Symptoms |

| Unadjusted | 0.73(0.55–0.96) | 0.72(0.59–0.88) | 0.73(0.57–0.94) |

| p = .022 | p = .001 | p = .013 | |

| Symptom frequency | 0.75(0.56–0.98) | 0.73(0.60–0.90) | 0.75(0.57–0.97) |

| p = .038 | p = .002 | p = .029 | |

| FEV1 | 0.73(0.55–0.96) | 0.72(0.59–0.88) | 0.73(0.57–0.94) |

| p = .023 | p = .001 | p = .015 | |

| Symptom frequency and FEV1 | 0.75(0.56–0.99) | 0.73(0.60–0.90) | 0.75(0.58–0.98) |

| p = .040 | p = .003 | p = .033 | |

Multiple logistic regression analysis.

Odds ratio per 1-point change in quality of life score.

Finally, we were unable to demonstrate any significant relationships between initial maternal overall quality of life or any individual domain and preeclampsia, preterm birth, low birth weight, or small for gestational age (data not shown).

Discussion

Asthma is estimated to occur in up to 8% to 10% of reproductive age women (13), the prevalence having risen substantially over the past 30 years (13) such that it is now likely the most common potentially serious medical problem to complicate pregnancy (1). Asthma presents two main problems during pregnancy. First, it may lead to chronic symptoms and acute episodes for the mother. Second, it may increase the risk of perinatal complications. Symptoms and pulmonary function have been studied as potential predictors of the impact of asthma during pregnancy on the mother and her fetus/neonate (5–7). We are not aware of any prior published study that measured asthma-specific quality of life during pregnancy. The results of the current study permit the conclusion that asthma-specific quality of life (overall and symptoms and emotions domain) scores in early pregnancy are related to subsequent asthma exacerbations during pregnancy but not to perinatal outcomes. Further, this study has shown that the relationship of quality of life to subsequent asthma exacerbations was independent of (above and beyond) the relationships between asthma exacerbations and asthma symptom frequency, FEV1, or both.

Several studies of nonpregnant patients have shown a relationship between asthma-specific quality of life and subsequent exacerbations requiring hospitalizations or emergency department visits (14–17). FEV1 (18–20) and symptom frequency (21–23) may also predict subsequent exacerbations, but we have unable to locate prior studies whose results reveal a relationship between asthma-specific quality of life and subsequent exacerbations above and beyond the effect of symptoms and FEV1. It is of interest that the symptoms domain of the AQLQ (which captures patient perception of the frequency of specific asthma symptoms on a 7-point scale from “all of the time” to “none of the time”) was a predictor of subsequent exacerbations above and beyond the symptom frequency assessment (number of days with symptoms) in our study. One potentially important difference is that the AQLQ symptom domain includes the frequency of interference with sleep due to asthma, which is considered a separate predictor from overall symptom frequency of poor asthma control (24).

One prior study in nonpregnant patients found a relationship between all of the AQLQ domains and subsequent exacerbations (15), whereas the current study only identified relationships between the symptoms and emotions domain and subsequent exacerbations. Besides not dealing with pregnant patients, differences between the two studies include a longer observation period in the previous study (12 months) and a different definition of exacerbations (asthma emergency department visits and hospitalizations only) (15). The strongest association with subsequent exacerbations in the current study was with the emotions domain, which includes questions regarding feeling “frustrated” regarding asthma and “concerned” about having asthma. It is possible that these issues do have a particularly strong impact during pregnancy.

More severe or uncontrolled asthma, based on symptoms or FEV1, has been associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia, preterm birth, low birth weight, or SGA (5–7). Triche et al. (6) observed a significant 2.8-fold increase in the incidence of preeclampsia in asthmatic women with daily symptoms compared to those who were symptom-free during pregnancy. From the same cohort, Bracken et al. (5) reported a significant 2.3-fold increase in SGA in infants of asthmatic women with daily symptoms compared to asymptomatic women. We have shown a relationship between lower maternal FEV1 during pregnancy and an increased incidence of gestational hypertension, preterm birth, and low-birth-weight infants (7). In contrast, the current study did not find a relationship between asthma-specific quality of life early in pregnancy and subsequent perinatal complications. One explanation may be that our measure of quality of life was a single measure early in pregnancy, whereas the symptoms and FEV1 in prior studies were assessed on multiple occasions throughout pregnancy.

What are the clinical implications of this study's findings? It is recommended that symptoms and FEV1 be carefully monitored in asthmatic patients during pregnancy to assess asthma control and guide therapy (1, 24). The results of the current study suggest that measuring asthma-specific quality of life may provide additional information regarding asthma impairment and risk of exacerbations above and beyond that provided by symptom frequency and FEV1. However, a specific prospective study would be necessary to prove this hypothesis.

In summary, we studied and now report the measurement of asthma-specific quality of life during pregnancy. Our findings suggest that this parameter in early pregnancy is related to subsequent asthma exacerbations but not perinatal morbidity. Further studies will be necessary to determine if measuring asthma-specific quality of life is advantageous in guiding asthma therapy during pregnancy so as to reduce exacerbations and if serial asthma-specific quality of life measurements during pregnancy would be related to perinatal complications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD27917, HD27915, HD21414, HD27883, HD27869, HD27861, HD27905, HD34122, HD21410, HD34116, HD34136, HD27860, HD34210, HD34208, and HD36801) and by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The following subcommittee members participated in protocol development, data management, and statistical analysis: Elizabeth Thom, Ph.D., and Valerija Momirova, M.S.; and in protocol development and coordination between clinical research centers: Risa Ramsey, R.N. Ph.D., and Gwendolyn Norman, R.N., M.P.H.

In addition to the authors, other members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network are as follow:

Wayne State University—Y. Sorokin, A. Millinder

The Ohio State University—F. Johnson, S. Meadows

University of Tennessee—B. Sibai

Medical University of South Carolina—J. P. Van Dorsten, B. A. Collins

University of Alabama at Birmingham—W. W. Andrews, R. L. Copper, S. Tate, A. Northen

University of Chicago—P. Jones, M. E. Brown, G. Mallett

University of Cincinnati—N. Elder, T. A. Siddiqi, V. Pemberton

University of Miami—S. Beydoun, C. Alfonso, J. Potter

University of Pittsburgh—R. Phillip Heine, M. Cotroneo, E. Daugherty

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center—M. L. Sherman

Thomas Jefferson University—M. DiVito, K. Smith

Wake Forest University Health Sciences—P. Meis, M. Harper, M. Swain, A. Luper

University of Texas at San Antonio—S. Barker, O. Langer

The George Washington University Biostatistics Center—E. Rowland, S. Brancolini

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute—J. Kiley

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development—D. McNellis, C. Catz

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report Managing asthma during pregnancy: Recommendations for pharmacologic treatment—2004 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schatz M, Dombrowski MP, Wise R, Thom EA, Landon M, Mabie W, et al. Asthma morbidity during pregnancy can be predicted by severity classification. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:283–288. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dombrowski MP. Outcomes of pregnancy in asthmatic women. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2006;26:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson PG, Smith R, Clifton VL. Asthma during pregnancy: Mechanisms and treatment implications. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:731–750. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00085704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bracken MB, Triche EW, Belanger K, Saftlas A, Beckett WS, Leaderer BP. Asthma symptoms, severity, and drug therapy: A prospective study of effects on 2205 pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:739–752. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Triche EW, Saftlas AF, Belanger K, Leaderer BP, Bracken MB. Association of asthma diagnosis, severity, symptoms and treatment with risk of preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:585–593. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000136481.05983.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schatz M, Dombrowski MP, Wise R, Momirova V, Landon M, Mabie W, et al. Spirometry is related to perinatal outcomes in pregnant women with asthma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, Ferrie PJ, Jaeschle R, Hiller TK. Evaluation of impairment of health related quality of life in asthma: Development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Thorax. 1992;47:76–83. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schatz M, Mosen D, Apter AJ, Zeiger RS, Vollmer WM, Stibolt TB, et al. Relationships among quality of life, severity and control measures in asthma: An evaluation using factor analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juniper EF, Wisniewski ME, Cox FM, Emmett AH, Nielsen KE, O'Byrne PM. Relationship between quality of life and clinical status in asthma: A factor analysis. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:287–291. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00064204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dombrowski M, Schatz M, Wise R, Thom EA, Landon M, Mabie W, et al. Randomized trial of inhaled beclomethasone diproprionate versus theophylline for moderate asthma during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juniper EF, Buist As, Cox Fm, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Validation of a standardized version of the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Chest. 1999;115:1265–270. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon HL, Triche EW, Belanger K, Bracken MB. The epidemiology of asthma during pregnancy: Prevalence, diagnosis, and symptoms. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2006;26:29–62. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisner MD, Ackerson LM, Chi F, Kalkbrenner A, Buchner D, Mendoza G, Lieu T. Health-related quality of life and future health care utilization for asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:46–55. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tierney WM, Roesner JF, Seshadri R, Lykens MG, Murray MD, Weinberger M. Assessing symptoms and peak expiratory flow rate as predictors of asthma exacerbations. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30311.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magid DJ, Houry D, Ellis J, Lyons E, Rumsfeld JS. Health-related quality of life predicts emergency department utilization for patients with asthma. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schatz M, Mosen D, Apter AJ, Zeiger RS, Vollmer WM, Stibolt TB, Leong A, Johnson MS, Mendoza G, Cook EF. Relationship of validated psycho-metric tools to subsequent medical utilization for asthma. J Allery Clin Immunol. 2005;115:564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D, German D, Lulla S, Thomas RG, Wilson SR. Prospective study of hospitalization for asthma: A preliminary risk factor model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:647–655. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.3.7881651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowie RL, Underwood MF, Revitt SG, Field SK. Predicting emergency department utilization in adults with asthma: A cohort study. J Asthma. 2001;38:179–184. doi: 10.1081/jas-100000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen F, Taylor DR, Flannery EM, Cowan JO, Greene JM, Herbison GP, Sears MR. Risk factors for hospital admission for asthma from childhood to young adulthood: A longitudinal population study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:220–227. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.125295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng Y-Y, Babey SH, Brown ER, Malcolm E, Chawla N, Lim YW. Emergency department visit for asthma: The role of frequent symptoms and delay in care. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;96:291–297. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diette GB, Krishnan JA, Wolfenden LL, Skinner EA, Steinwachs DM, Wu AW. Relationship of physician estimate of underlying asthma severity to asthma outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:546–552. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tinkelman DG, McClure DL, Lehr TL, Schwartz AL. Relationships between self-reported asthma utilization and patient characteristics. J Asthma. 2002;39:729–736. doi: 10.1081/jas-120015796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel 3: Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S93–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]