Abstract

Activation of CRH transcription requires phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and translocation of the CREB coactivator, transducer of regulated CREB activity (TORC) from cytoplasm to nucleus. In basal conditions, transcription is low because TORC remains in the cytoplasm, inactivated by phosphorylation through Ser/Thr protein kinases of the AMP-dependent protein kinases (AMPK) family, including salt-inducible kinase (SIK). To determine which kinase is responsible for TORC phosphorylation in CRH neurons, we measured SIK1 and SIK2 mRNA in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of rats by in situ hybridization. In basal conditions, low mRNA levels of the two kinases were found in the dorsomedial paraventricular nucleus, consistent with location in CRH neurons. One hour of restraint stress increased SIK1 mRNA levels, whereas SIK2 mRNA showed only minor increases. In 4B hypothalamic neurons, or primary cultures, SIK1 mRNA (but not SIK2 mRNA) was inducible by the cAMP stimulator, forskolin. Overexpression of either SIK1 or SIK2 in 4B cells reduced nuclear TORC2 levels (Western blot) and inhibited forskolin-stimulated CRH transcription (luciferase assay). Conversely, the nonselective SIK inhibitor, staurosporine, increased nuclear TORC2 content and stimulated CRH transcription in 4Bcells and primary neuronal cultures (heteronuclear RNA). Unexpectedly, in 4B cells specific short hairpin RNA knockdown of endogenous SIK2 but not SIK1 induced nuclear translocation of TORC2 and CRH transcription, suggesting that SIK2 mediates TORC inactivation in basal conditions, whereas induction of SIK1 limits transcriptional activation. The study provides evidence that SIK represses CRH transcription by inactivating TORC, providing a potential mechanism for rapid on/off control of CRH transcription.

CRH produced by parvocellular neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN; and other brain areas) is the major regulator of hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis activity as well as behavioral and autonomic responses to stress (1, 2). Dysregulation of CRH neuronal function is associated with stress-related psychiatric disease, and abnormal CRH production is associated with some of these disorders (3–6). Activation of the CRH neuron leads to rapid CRH release, which is followed by induction of CRH transcription leading to CRH synthesis and restoration of releasable pools of the peptide (7). Therefore, elucidation of the mechanisms driving CRH transcription is important for understanding the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders and identifying new therapeutical approaches.

It is currently accepted that activation of CRH transcription involves stimulation of cAMP/protein kinase A-dependent pathways and interaction of phospho-cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) with a cAMP-responsive element (CRE) at position −229 in the CRH promoter (8–12). More recently it has become evident that phospho-CREB is not sufficient and that activation of CRH transcription requires nuclear translocation of the CREB coactivator, transducer of regulated CREB activity (TORC) (13, 14). In the nucleus, TORC interacts with CREB at the CRH promoter, allowing initiation of CRH transcription. Moreover, the termination of CRH transcription is associated with the release of TORC from the CRH promoter (13, 14). Of the three TORC subtypes described (TORC1, TORC2, and TORC3), TORC2 is the major player in the regulation of CRH transcription (14). In basal conditions, TORC is located in the cytoplasm in a phosphorylated inactive state bound to the scaffolding protein 14-3-3 (15, 16). TORC is phosphorylated by members of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) family of serine/threonine protein kinases, including salt-inducible kinase (SIK). Protein kinase A inactivates these kinases, thus preventing TORC phosphorylation and allowing its release from the scaffolding protein 14-3-3 and translocation to the nucleus, in which it interacts with CREB (17). In addition, the calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase, calcineurin, dephosphorylates and therefore facilitates TORC activation (18).

SIK1, also known as sucrose non-fermenting-like kinase, was originally identified in the adrenal gland of sodium loaded rats and shown to act as a repressor of cAMP-dependent steroidogenesis (19). After the identification of TORC, it became evident that the mechanism by which SIK1 inhibits steroidogenesis involves the phosphorylation and inactivation of TORC. By sequence homology, two additional forms were identified: SIK2, shown to be highly expressed in adipocytes, and SIK3, more ubiquitously expressed and of unknown function (20).

Although the requirement for nuclear translocation of TORC for activation of CRH transcription has been established (13, 14), the mechanism of the nuclear import and export of TORC in hypothalamic neurons has not been studied. The purpose of this study was to determine whether SIK1 and SIK2 are present in the PVN and their potential involvement in the transcriptional repression of CRH by inactivating TORC.

Materials and Methods

Animals and procedures

Male Sprague Dawley rats, 250–300 g, were acclimated to the animal facility conditions for 5 d and killed either in basal conditions or restraint stress for up to 60 min and killed at 15, 30, 60, or 180 min. Brains were rapidly removed after decapitation and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m borate buffer (pH 9.5) for 48 h before transferring to the same fixative containing 12% sucrose for an additional 48 h. After fixation, brains were frozen in isopentane cooled in dry ice and stored at −80 C until sectioned in a cryostat into 15-μm coronal sections throughout the hypothalamic region. Experiments were performed in the morning with rats killed between 0900 and 1200 h. All procedures and experimental protocols were performed according to National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Animal Care and Use Committee.

Constructs and reagents

The CRH promoter-driven luciferase reporter gene (pGL3-CRHp) was created by two-step cloning, using a 613-bp restriction fragment containing the CRH promoter (−498 to +115 bp relative to the proximal transcription start point), obtained by XbaI/KpnI digestion of the CRH gene clone prCRHBglII (provided by Dr. Audrey Seasholtz, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), as previously described (11).

Full-length cDNA sequences of SIK1 cloned into pTarget (Promega, Madison, WI) and SIK1 and SIK2 cloned into the BamHI/EcoRI sites of pEGFPC for SIK1 and BamHI/NotI for SIK2 (21) were used for SIK overexpression experiments in 4B cells (21). The pTarget SIK1 vector was used to confirm the specificity of the SIK1 antibody in the Western blot. The EGFP-SIK1 and SIK2 vectors were used to examine the effects of SIK overexpression on TORC2 translocation and CRH transcription because of their much higher expression efficiency. For blocking endogenous SIK, 4B cells were transfected with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeted against human SIK1 (GCCACTTGAGTGAAAACGAGG) and SIK2 mRNA (AATCTACCGAGAAGTACAAAT) or nonspecific sequences, cloned into pBluescript/U6, kindly provided by Dr. Marc Montminy (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA).

For in situ hybridization probes, plasmids harboring rat SIK1 (639 bp), and SIK2 (628 bp) cDNA fragments were created by cloning PCR fragments (obtained from 4B cDNA) into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). The sequence of the PCR primers used for obtaining the cDNA fragments for the probes were: forward, ACGGGCACTTGAGTGAAAAC, and reverse, AGCTGCTGTTCTGTAGAGAC, for SIK1, and forward, AGGCACAAACCGTGGGGCTACC, and reverse, TAGGGGACCGGTTATGGGCTTCA, for SIK2. The sequences of the quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) primers were: forward, CGGCGAATAGCTTAAACCTG, and reverse, CAGGTGACCCTTCCTTGGAGA, for CRH heteronuclear (hn) RNA; forward, ACCAGCAGAGGCTGCTCCAGT, and reverse, GGCGTTGGCAGCAGTGGGAT, for SIK1, and forward, CGTTCACGCTCCCGTCGTC, and reverse, CAGCGTGCCCTCGAYGTCGTAG, for SIK2 mRNA.

Forskolin was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences/Biomol International (Plymouth Meeting, PA) and staurosporine from EMD Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ).

In situ hybridization histochemistry

Plasmids were linearized with appropriate restriction enzymes and then used to synthesize sense and antisense 35S-UTP-labeled cRNA probes using the Promega Gemini kit (Promega Inc., Madison WI) and appropriate RNA polymerases. In situ hybridization histochemistry was performed as previously described (22). Adjacent sections were hybridized with a 35S-UTP-labeled cRNA probes transcribed from each of CRH hnRNA, SIK1, and SIK2 cDNA. Sections hybridized with the radiolabeled sense and antisense riboprobes were exposed to Mamoray HDR-C x-ray film (Agfa Corp., Goose Creek, SC) for 28, 13, and 17 d, respectively, for CRH hnRNA, SIK1, and SIK2 mRNA. Sense strand cRNA probes did not yield detectable hybridization for any of genes examined (data not shown). Gray-scale images from the Mamoray HDR-C film were obtained using IPLab Spectrum software for the Mac (version 3.9; Signal Analytics, Vienna, VA) controlling an uncooled QImaging micropublisher charge-coupled device digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, British Columbia, Canada).

Cell cultures, transfection, and treatments

Hypothalamic 4B cells, provided by Dr. John Kasckow (VA Pittsburgh Health Care System, Cincinnati, OH) were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). For reporter gene assays, cells were transfected by electroporation using a Nucleofector (Lonza Walkersville, Inc., Walkersville, MD) and solution V (Lonza) purchased from the manufacturer. Aliquots of 5 million 4B cells were transfected with 2.5 μg pGL3-CRHp plasmid and 75 ng of renilla luciferase construct to normalize for transfection efficiency, with or without the cotransfection with either 5 μg of pEGFP, pEGFP-SIK1, or pEGFP-SIK2, for overexpression or with BS/U6-nonspecific, BS/U6-shSIK1, or BS/U6-shSIK2, for knocking down endogenous SIK. The maximal amount of DNA transfected was 10 μg. After transfection, cells were resuspended in DMEM containing 10% horse serum and 10% fetal bovine serum and plated into 48-well culture plates at a density of 50,000 cells/well for the luciferase assay; 500,000 cells per six-well plates for SIK1 and SIK2 mRNA determination; or 2.5 × 106 cells per 10-cm plates for Western blot. Experiments were performed 24 h after transfection for the overexpression experiments and 48 h after transfection for SIK knockdown experiments.

Primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons were obtained by collagenase dispersion from fetal Sprague Dawley rats, embryonic d 18 as previously described (12). Cells were resuspended in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and plated at a density of 1.4 × 106 cells/well in six-well plates coated with poly-l-lysine. After 24 h incubation, media were changed to neurobasal media (Life Technologies, Inc./Invitrogen) with B27 supplement (Invitrogen) and 3 d later cultured in the presence of 5 μm cytosine arabinoside (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to prevent glial proliferation. On d 10, cells were changed into serum-free/B27 supplement-free neurobasal medium containing 0.1% BSA for 4 h before treatment as stated in Results and the figure legends.

Luciferase assays

Twenty-four hours (for overexpression) or 48 h (for endogenous SIK knockdown) after transfection, cells were preincubated for 1 h in serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA before the addition of 1 or 3 μm forskolin or vehicle. After 6 h incubation, media were removed and cells lysed by the addition of 100 μl of passive lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activity in cell lysates was determined using reagents from Promega (dual luciferase assay system; Promega), as previously described (10).

Immunoblotting

Twenty-four or 48 h after transfection (for overexpression or endogenous SIK knockdown, respectively), cells cultured in 10-cm dishes were preincubated for 2 h in serum-free DMEM containing 0.1% BSA before the addition of 1 or 3 μm forskolin. After an additional 30-min incubation, medium was removed and nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins extracted using NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After the quantification of protein concentration, Western blots were performed as previously described (12), using 15 μg of protein and antibodies for TORC2 (Calbiochem/EDM Chemicals) at 1:6000 dilution, SIK1 (by H.T.) at 1:1000 dilution, or SIK2 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) at a dilution of 1:1500. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, immunoreactive bands were detected using ECL Plus TM reagents (GE Amersham Biosciences, Indianapolis, IN) followed by exposure to BioMax MR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). The intensity of the bands was quantified using the software, ImageJ [developed at the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD), which is freely available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/]. Results were corrected by the intensity of histone deacetylase 1 or β-actin bands, used as loading controls for nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins, respectively.

Immunostaining for TORC2 in 4B cells

Hypothalamic 4B cells cultured in poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips were treated with either vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide, 0.1%) or forskolin for 30 min before fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 min. Immunohistochemistry for TORC2 was performed as previously described using a rabbit anti-TORC2 antibody (Calbiochem; 1:500) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat antirabbit antibodies (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes; 1:1000). After mounting using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), images of cell cultures taken as a single plane scans on a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510; Jena, Germany) at ×60 magnification were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, Mountain View, CA).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR for CRH hnRNA and SIK1 and SIK2 mRNA

After treatment of 4B cells or primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Hopkinton, MA), followed by purification using RNeasy minikit reagents and column deoxyribonuclease digestion (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) to remove genomic DNA contamination. cDNA was reverse transcribed from 300–750 ng of total RNA as previously described (10). CRH primary transcript levels (hnRNA) in primary cultures were measured using primers designed to amplify the intron, and SIK1 and SIK2 mRNA accumulation was evaluated using primers designed to amplify exonic fragments. Power SYBR green PCR mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used for amplification with each primer at a final concentration of 200 nm and 1.5 μl of cDNA for a total reaction volume of 12.5 μl. PCR were performed on spectrofluorometric thermal cycler 7900 HT Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) as previously described (14). Samples were amplified by an initial denaturation at 50 C for 2 min, 95 C for 10 min, and then cycled (40–45 times) using 95 C for 15 sec and 60 C for 1 min. Levels of hnRNA and mRNA were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA as determined in separate qRT-PCR reactions. The absence of RNA detection when the reverse transcription step was omitted indicated the lack of genomic DNA contamination in the RNA samples.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± sem from the values in the number of observations indicated in the legend of the figures. The statistical significance of the differences between groups was determined by one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher protected least-significant difference post hoc test unless specified in Results or the figure legends. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Effect of restraint stress on SIK1 and SIK2 in the PVN

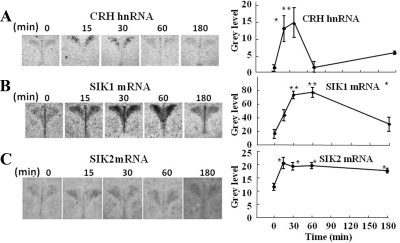

The potential involvement of SIK in the regulation of CRH transcription was studied by examining the level of the RNA for these kinases in the PVN in relation to CRH hnRNA levels in controls and rats subjected to restraint stress, using in situ hybridization. CRH hnRNA levels were very low in basal conditions, increased rapidly by about 6-fold at 15- and 30-min restraint stress, and returned to basal levels by 60 min (Fig. 1-A). Both SIK1 and SIK2 mRNA were present in the PVN. SIK1 mRNA showed diffuse low levels throughout the PVN in basal conditions but increased progressively from 15 to 60 min and then declined to levels still significantly higher than basal by 180 min, exclusively in the dorsomedial region (Fig. 1B). In contrast, SIK2 mRNA was very low, but restraint stress caused a small but consistent 80% increase in the hybridization signal for SIK2 mRNA in the dorsomedial region by 15 min, which persisted up to 180 min (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Time course of the effect of restraint stress on levels of CRH hnRNA (A), SIK1 (B), and SIK2 (C) mRNA in the PVN. Images are representative of data obtained by in situ hybridization in coronal sections of the hypothalamic region at the level of the PVN of rats subjected to restraint stress for the time periods indicated in the figure. The graphs represent the pooled data from four rats per group. *, P < 0.05 vs. basal (0 min); **, P < 0.01 vs. 0 min. Film exposure was 28, 13, and 17 d for CRH hnRNA, SIK1, and SIK2 mRNA, respectively.

Forskolin induces SIK1 mRNA in hypothalamic neurons

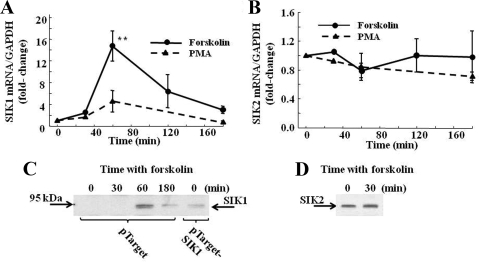

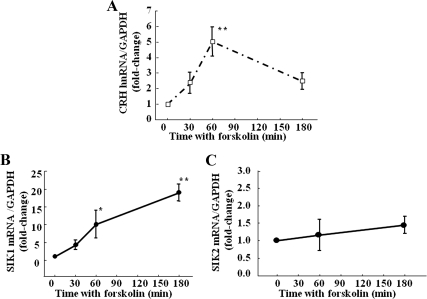

To determine whether SIK is inducible by cAMP in hypothalamic neurons, we examined the changes in SIK1 and SIK2 mRNA in the hypothalamic cell line 4B and in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons after incubation with the adenylate cyclase stimulator, forskolin. Consistent with the findings in vivo, in 4B cells, basal levels of SIK1 mRNA measured by qRT-PCR were higher than those of SIK2 mRNA (cycle threshold 26 and 28, respectively). As shown in Fig. 2A, incubation of 4B cells with 3 μm forskolin increased SIK1 mRNA levels by about 14-fold at 60 min (P < 0.01 vs. basal) and returned to levels not significantly different from basal by 120 and 180 min. In contrast, after incubation with the phorbol ester, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), levels of SIK1 mRNA showed a tendency to increase by 1 h, but the changes were not statistically significant (Fig. 2A) (P = 0.3). No changes in SIK2 mRNA levels were observed after incubation of the cells with forskolin or PMA (Fig. 2B). Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic proteins from 4B cells transfected with the empty expression vector, pTarget, using an antibody against SIK1 failed to detect any specific bands in basal conditions but a band of 95 kDa in the molecular mass range of SIK1 became evident at 60 min. The SIK1 band decreased by 120 min, but it was still detectable (Fig. 2C). The size of this band was identical to a band recognized by the SIK1 antibody in 4B cells overexpressing SIK1 after transfection with pTarget-SIK (Fig. 2C). Unexpectedly, a band corresponding to the molecular size of SIK2 was readily detectable in basal conditions and at 30 min incubation with forskolin (Fig. 2D). In primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons, forskolin caused a significant increase in CRH hnRNA reaching a maximum of 5-fold by 1 h (P < 0.01) and returning near basal levels by 3 h. Forskolin also increased SIK1 mRNA (Fig. 3B), but in contrast to the effects of stress in vivo or 4B cells, the increase was more gradual and prolonged, with a 5.3-fold change at 1 h (P < 0.05) and a progressive increase up to about 15.2-fold at 3 h (P < 0.01), at which time CRH hnRNA levels had already declined (Fig. 3A). Similar to 4B cells, forskolin had no effect on SIK2 mRNA levels in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 2.

Time course of the effect of forskolin and PMA on SIK1 (A) and SIK2 (B) mRNA levels, measured by qRT-PCR and SIK1 (C) and SIK2 (D) proteins in cytoplasm measured by Western blot in the hypothalamic neuronal cell line, 4B. Western blots for SIK1 were performed in proteins transfected with the empty expression vector, pTarget, (endogenous SIK1) or cells transfected with pTarget-SIK1 (overexpressed SIK1). For SIK2, proteins were from cells transfected with the empty expression vector, pBluescrit/U6; thus, the band recognized by the SIK2 antibody represents endogenous SIK2. Data points are the mean and se of the values obtained in four to five experiments expressed as fold change from basal values. **, P < 0.01 vs. basal (0 min). Neither SIK1 nor SIK2 protein were detectable in nuclear proteins. GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Fig. 3.

Time course of the effect of forskolin on endogenous levels of CRH hnRNA (A), SIK1 mRNA (B), and SIK2 mRNA (C) in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons. Data points are the mean and se of pooled data from four to seven experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 vs. control (time 0). GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

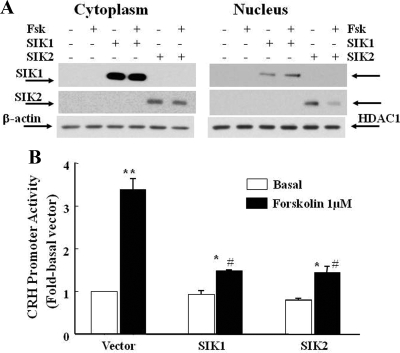

SIK1 and SIK2 overexpression inhibits CRH promoter activity and nuclear translocation of TORC2

To establish whether SIK is able to influence CRH transcription, 4B cells were cotransfected with a CRH promoter-driven luciferase construct (pGL3-CRHp) and the expression vectors, EGFP-SIK1 and EGFP-SIK2, or the empty vector. Western blot using SIK antibodies confirmed the effectiveness of the transfection in overexpressing SIK1 and SIK2. As shown in Fig. 4A, endogenous SIK1 and SIK2 protein levels in 4B cells transfected with the empty vector were not detectable with the exposure time used. On the other hand, bands of 110 and 140 kDa corresponding to the molecular mass of EGFP-SIK1 and EGFP-SIK2 were readily detected in transfected cells (Fig. 4A). The effect of SIK1 or SIK2 overexpression on CRH promoter activity is shown in Fig. 4B. Incubation of 4B cells, cotransfected with the empty vector and CRHp-luc, with 1 μm forskolin increased CRH promoter activity by about 3.5-fold over the basal values (P < 0.01). Cotransfection of SIK1 or SIK2 had no significant effect on basal CRH promoter activity, but it markedly reduced the stimulatory effect of 1 μm forskolin to 1.5- and 1.8-fold, respectively (P < 0.05 vs. forskolin in cells transfected with the empty vector or the respective basal).

Fig. 4.

Effect of SIK1 and SIK2 overexpression on CRH promoter activity in 4B cells cotransfected with SIK1 or SIK2 and a CRH promoter-driven luciferase reporter gene. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with forskolin (Fsk) before protein or RNA isolation for Western blot or qRT-PCR. The Western blot image shows specific bands corresponding to EGFP-SIK1 and EGFP-SIK2 in cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins is shown in A. Endogenous SIK1 and SIK2 were undetectable with the short exposure time required to detect overexpressed SIK proteins. The effect of SIK overexpression on CRH promoter activity measured 24 h after transfection is shown in B. The bars represent the mean and se of pooled data from three experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. the respective basal; **, P < 0.01 vs. the respective basal; #, P < 0.01 lower than forskolin in cells transfected with the empty EGFP-N1 vector. HDAC, Histone deacetylase.

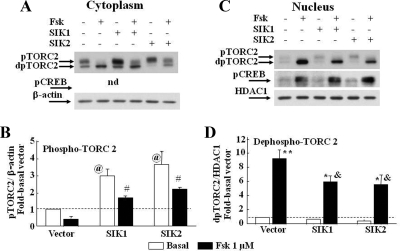

To determine whether the decrease in CRH promoter activity in cells overexpressing SIK1 or SIK2 was related to changes in nuclear translocation of TORC2, we examined the levels of TORC2 in cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins by Western blot in transfected 4B cells (Fig. 5). Immunoblot with the TORC2 antibody revealed bands of 95 and 85 kDa corresponding to the phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms of TORC2 (23). In cells transfected with the empty vector, incubation with forskolin caused a decrease in phosphoTORC2 (upper band) in cytoplasmatic proteins (P < 0.05; Fig. 5, A and B) and a marked 9-fold increase in the lower band (dephospho-TORC2) in nuclear proteins (Fig. 5, C and D; P < 0.01). Overexpression of either SIK1 or SIK2 increased phospho-TORC2 in the cytoplasm by about 3-fold (P < 0.01) and decreased forskolin-induced translocation of dephospho-TORC2 to the nucleus by about 30% (P < 0.05, EGFP-SIK1 or EGFP-SIK2 transfected cells vs. forskolin in cells transfected with the empty vector) (Fig. 5, C and D). In contrast, forskolin-induced increases in phospho-CREB in the nucleus were unaffected by SIK1 or SIK2 overexpression (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Effect of SIK1 and SIK2 overexpression on forskolin (Fsk)-induced nuclear levels of phospho-CREB (pCREB), phosphorylated (pTORC2), and dephosphorylated TORC2 (dpTORC2). Cytoplasmic (A and nuclear (C and D) proteins of 4B cells transfected with expression vectors for SIK1 or SIK2 were subjected (A and B) to Western blot analysis for TORC2 and phospho-CREB (pCREB). Transfection with either EGFP-SIK1 or EGFP-SIK2 increased basal phospho-TORC2 in the cytoplasm and reduced dephospho-TORC2 translocation to the nucleus, without affecting nuclear content of phospho-CREB. Bars (C and D) represent the mean and se of the data obtained in three or four experiments. Quantification of dephospho-TORC2 in the cytoplasm and phospho-TORC2 in the nucleus showed no remarkable changes (not shown). @, P < 0.01 vs. empty vector (vector) basal; #, P < 0.05, forskolin vs. respective basal; *, P < 0.05 vs. empty vector Fsk-induced; **, P < 0.01, Fsk vs. basal; &, P < 0.05 vs. forskolin vector. nd, Nondetectable; HDAC, histone deacetylase.

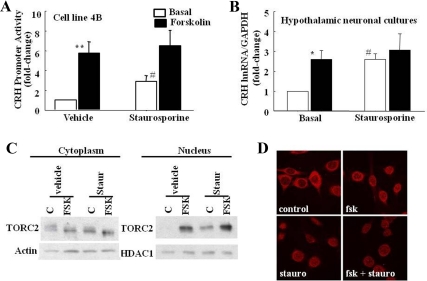

Inhibition of SIK by staurosporine induces nuclear translocation of TORC2 and CRH transcription

The protein nonspecific kinase inhibitor, staurosporine, shown to be an effective inhibitor of SIK activity (24), was used to study the effect of SIK inhibition on TORC translocation and CRH transcription. Incubation of CRHp-luc-transfected 4B cells with 10 nm staurosporine caused a 2.9-fold increase in basal CRH promoter activity (P < 0.01 when compared using log transformation of the data or by t test). Forskolin increased CRH promoter activity by 6-fold over basal levels (P < 0.01). Staurosporine had no effect on maximal stimulation by forskolin (P = 0.5), but because of the higher basal levels, it reduced the fold change over basal (2.2-fold, P = 0.04) (Fig. 6A). In primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons, staurosporine increased basal CRH hnRNA (P < 0.01) to levels similar to those observed with forskolin (P < 0.01) and had no further effect on the maximal increases elicited after 45 min incubation with forskolin (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Effect of the protein kinase inhibitor, staurosporine, on CRH transcription and nuclear translocation of TORC2 in hypothalamic neurons. A, Effect of the protein kinase inhibitor, staurosporine, on CRH promoter activity in 4B cells transfected with a CRH-promoter driven luciferase reporter gene. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were incubated with forskolin for 6 h, 30 min after addition of 10 nm staurosporine. B, Effect of staurosporine on forskolin-stimulated CRH hnRNA in primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons. Forskolin was added 30 min after 10 nm staurosporine, and incubation continued for an additional 45 min. The bars represent the mean and se of the results of three experiments, expressed as fold change over the basal values. *, P < 0.01, forskolin vs. basal; # P < 0.01, staurosporine vs. vehicle. C, Representative Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins of 4B cells. Staurosporine or vehicle was added 30 min before incubation with forskolin for an additional 30 min. HDAC, Histone deacetylase. D, Immunohistochemical analysis of TORC immunoreactivity in 4B cells treated as in C.

The stimulatory effect of staurosporine on CRH transcription in the reporter gene assay and in hypothalamic cultures was associated with increases in TORC2 translocation to the nucleus. As shown by the Western blot images in Fig. 6C, forskolin caused the expected increases in the lower band corresponding to dephosphorylated TORC2 in the cytoplasm and a marked increase in nuclear TORC2. Staurosporine alone increased the dephosphorylated TORC2 band in the cytoplasm and nucleus but had no effect on forskolin-induced TORC translocation to the nucleus. The Western blot results were confirmed by immunohistochemistry in 4B cells. As shown in Fig. 6D, most TORC2 immunostaining was located in the cytoplasm in basal conditions, but incubation with either forskolin or staurosporine caused a shift of the immunostaining to the nucleus. Consistent with the Western blot, staurosporine had no effect on forskolin-stimulated nuclear translocation of immunoreactive TORC2.

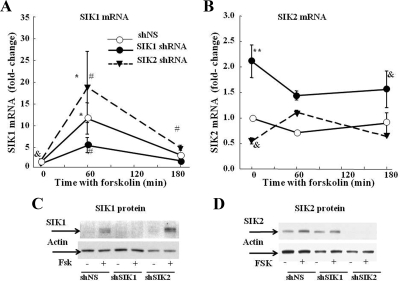

Effect of shRNA blockade of SIK on nuclear translocation of TORC2 and CRH transcription

To further study the role of SIK in the regulation of CRH transcription, experiments were conducted 48 h after transfecting 4B cells with shRNA constructs targeting either SIK1 or SIK2 to block endogenous SIK production. Incubation of cells transfected with nonspecific shRNA with forskolin caused a marked 11-fold increase in SIK1 mRNA levels at 1 h (P < 0.01 vs. basal) and decreased by 3 h to levels only 2.7-fold the basal (P < 0.01). Transfection of SIK1 shRNA reduced basal SIK1 mRNA to 54 ± 9% (P < 0.05) of the value in cells transfected with the empty vector, but the difference was significant only after log transformation of the data or by t test (P < 0.05). However, SIK1 shRNA significantly reduced the induction by forskolin (5-fold vs. 11-fold in cells tranfected with nonspecific shRNA, P < 0.01) and prevented the increase in SIK1 protein induced after incubation with forskolin. In contrast, a significantly larger increase of 18-fold in SIK1 mRNA was observed after 1 h forskolin in cells transfected with SIK2 shRNA (P < 0.01 vs. 1 h forskolin in cells transfected with nonspecific shRNA, Fig. 7A). This compensatory increase in SIK1 expression after SIK2 shRNA was also evident on forskolin-stimulated SIK1 protein, measured by Western blot (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Effect of SIK1 and SIK2 shRNA on SIK1 (A and B) and SIK2 (C and D) expression in 4B cells Forty-eight hours after transfection with SIK1 or SIK2 shRNA, cells were incubated with forskolin for up to 3 h before RNA isolation for qRT-PCR. Data points are the mean and se of the values obtained in three to four experiments. *, P < 0.01, forskolin vs. basal (0 min); #, P < 0.05, shNS vs. shSIK2 or shSIK1; &, P < 0.05 basal SIK1 or SI2 shRNA vs. shNS, after log transformation of the data or by t test. C, Western blot image for endogenous SIK1 in cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins from 4B cells transfected with nonspecific shRNA (shNS), SIK1 (shSIK1), or SIK2 (shSIK2) shRNA. Fsk, Forskolin. D, Western blot image for endogenous SIK2 in cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins from 4B cells transfected with nonspecific shRNA (shNS), SIK1 (shSIK1), or SIK2 (shSIK2) shRNA. Cells were incubated with 3 μm forskolin 48 h after transfection. Western blot images are representative of two experiments. Endogenous SIK and SIK2 protein were undetectable in nuclear proteins by Western blot.

As shown in Fig. 7B, forskolin had no significant effect on SIK2 mRNA in cells transfected with nonspecific shRNA. However, basal SIK2 mRNA levels were about 45% lower in cells transfected with SIK2 shRNA vs. nonspecific shRNA (P = 0.01 after log transformation of the data). Blockade of SIK1 expression by SIK1 shRNA dramatically increased basal levels of SIK2 mRNA (P < 0.01), and these levels tended to decline after incubation with forskolin, but they were still significantly higher than in cells transfected with nonspecific shRNA (P < 0.05 vs. 3 h forskolin in cells transfected with nonspecific shRNA after log transformation of the data, Fig. 7B). The SIK2 antibody recognized a 120-kDa band corresponding to the molecular mass of SIK2 in cytoplasmic proteins of cells transfected with nonspecific or SIK1 shRNA. This band was absent in cells transfected with SIK2 shRNA (Fig. 7D).

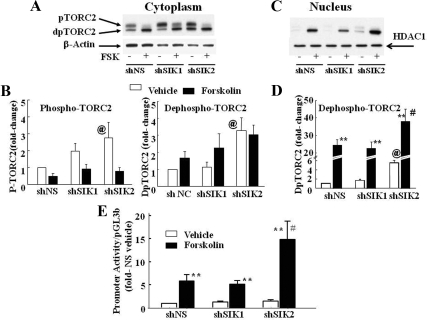

The effect of SIK blockade on the nuclear translocation of TORC2 is shown in Fig. 8. Incubation of the cells with forskolin caused the expected shift to the faster migrating band corresponding to dephosphorylated TORC2 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 8, A and B) and made evident a band corresponding to dephosphorylated TORC2 in the nucleus (Fig. 8, C and D). Unexpectedly, transfection of SIK1 shRNA had no significant effect on nuclear TORC2 levels in basal conditions or after incubation with forskolin, and transfection of SIK1 or SIK2 shRNA increased phosphorylated TORC2 in the cytoplasm. However, SIK2 shRNA increased the intensity of the band corresponding to dephosphorylated TORC in the cytoplasm (P < 0.01, Fig. 8, A and B) and significantly increased basal and forskolin-stimulated dephosphorylated TORC2 in the nucleus (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively, Fig. 8, C and D).

Fig. 8.

Effect of SIK1 and SIK2 shRNA blockade on forskolin-induced nuclear translocation of TORC2 and CRH transcription. Images show representative Western blot for TORC2 in cytoplasmic (A) and nuclear proteins (C) of 4B cells transfected 48 h earlier with expression vectors for a nonspecific shRNA (shNS) or shRNA for SIK1 (shSIK1) or SIK2 (shSIK2). Cells were processed for nuclear and cytoplasmic protein isolation 30 min after incubation with vehicle or 3 μm forskolin. The bars represent the mean and se of the pooled semiquantitative analysis of phospho- and dephospho-TORC2 in the cytoplasm (B) and dephospho-TORC2 in the nucleus (D) in four experiments. **, P < 0.01, forskolin vs. basal; #, P < 0.01, forskolin shSIK2 vs. forskolin shNS or shSIK1; @, P < 0.01, basal shSIK2 vs. basal shNS or shSIK1. The effect of SIK1 or SIK2 shRNA blockade on forskolin-induced CRH promoter activity is shown in E. *, P < 0.01, basal vs. forskolin; #, P < 0.01, forskolin shSIK2 vs. forskolin in shNS and shSIK1. HDAC, histone deacetylase; dpTORC2, dephosphorylated TORC2; Fsk, forskolin.

SIK2 shRNA tended to increase basal CRH promoter activity in the reporter gene assay and significantly potentiated the stimulatory effect of forskolin (Fig. 8C). Forskolin induced 5.9- and 5.2-fold increases in CRH promoter activity in cells tranfected with negative control and SIK1 shRNA, respectively (P < 0.01), whereas a 14.8-fold was observed in cells transfected with SIK2 shRNA (P < 0.01 vs. basal and P < 0.05 vs. forskolin in cells transfected with nonspecific shRNA or SIK1 shRNA).

Discussion

We previously reported that cAMP-dependent translocation of the CREB coactivator TORC to the nucleus, and its interaction with CREB at the CRE of the CRH promoter is critical in the activation of CRH transcription (13, 14). The present study provides in vivo and in vitro evidence indicating that SIK plays a role in the regulation of CRH transcription by controlling the activity and trafficking of the coactivator, TORC. The topographic location of SIK1 and SIK2 shown by in situ hybridization in the dorsal zone of the medial parvicellular part (mpd) of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus suggests that both SIK types are present in CRH neurons. Moreover, restraint stress caused dramatic induction of SIK1 mRNA in the PVN mpd. Although expression of SIK2 was lower than that of SIK1 (judging by the longer exposure require for visualizing the in situ hybridization signal), the small but significant increase in SIK2 mRNA during stress suggests that both SIK forms are involved in the regulation of CRH neurons in the PVN. Changes in SIK1 mRNA levels related to function have also been reported in the pineal gland, in which SIK1 levels display marked day/night variations (25). Moreover, in cultured pinealocytes shRNA inhibition of SIK1 potentiated the stimulatory effect of norepinephrine on arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase transcription and other cAMP-regulated genes (25). In addition to SIK1 and SIK2, in situ hybridization evidence of low levels of AMPK mRNA in the PVN mpd and a small induction 2 h after the end of restraint stress (26) suggest that AMPK could also be involved in CRH neuronal function. It is clear that activated AMPK can phosphorylate a wild-type but not Ser171Ala mutant GST-TORC2 (161–181) peptide in vitro (27). However, there is no convincing evidence that AMPK phosphorylates TORC. Consistent with previous reports indicating that AMPK overexpression do not repress CRE-driven luciferase in human embryonic kidney 293 cells (24), experiments in our laboratory have failed to show any effect of AMPK transfection or the AMPK agonist, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-beta-D-ribofuranoside on CRH promoter-driven luciferase activity in 4B cells (Liu Y., and G. Aguilera, unpublished observations). The role of AMPK on the regulation of CRH transcription is under current investigation, but the present data strongly suggest that SIK1 are SIK2 are involved.

Although the hypothalamic cell line 4B does not express sufficient CRH for studying endogenous CRH transcription, the cell line has proven to be a good model for studying the transcriptional regulation of CRH using reporter gene assays (10, 11, 28, 29). Consistent with the experiments in vivo, SIK1 mRNA was markedly inducible by the adenylate cyclase stimulator, forskolin, in 4B cells. It is noteworthy that a band of 95 kDa was recognized by the SIK1 antibody after incubation of the cells with forskolin for 1 h. Because the apparent molecular size of SIK1 varies slightly from 85 to 95 kDa, depending on the electrophoresis conditions (Takemori, H., unpublished observations), this size is within the expected range for SIK1. Moreover, the identical band observed in cells transfected with the pTarget-SIK1 expression vector confirms that the band corresponds to SIK1. The increases in SIK1 protein are likely the result of translation of new protein, although SIK protein stabilization may also contribute to the increase in protein level. In this regard, it has been shown that SIK is a labile protein, but its activation by phosphorylation at Thr182 confers stability (30). The upstream protein kinase responsible for Thr182 phosphorylation is liver kinase B1 (LKB1) (24, 31), and disruption of this phosphorylation by mutagenesis results in rapid SIK degradation (24). Because in addition to inactivating SIK by phosphorylation at Ser 577 (20), protein kinase A can activate LKB1 (32), forskolin could later activate and stabilize newly synthesized SIK by activating LKB1.

The effects of SIK overexpression and knockdown on nuclear translocation of TORC2 demonstrated in this study by the Western blots and immunohistochemistry clearly show that SIK regulates TORC activity in this cell line. The concomitant reduction in TORC2 translocation to the nucleus and CRH promoter activity cotransfected with SIK expression vectors indicates that both SIK1 and SIK2 are able of repressing CRH transcription by preventing TORC trafficking. SIK is capable of phosphorylating and sequestering in the cytoplasm all three TORC isoforms (24). Although TORC2 is the predominant isoform involved in regulating CRH transcription, TORC1 and especially TORC3 may also play a role. Therefore, any regulatory role of SIK on CRH transcription may not be limited to TORC2.

The results of the experiments using pharmacological or shRNA suppression of SIK demonstrate that both SIK1 and SIK2 are involved in the regulation of CRH transcription. The protein kinase inhibitor, staurosporine, has been shown to be an effective inhibitor of SIK (24) and can stimulate expression of other genes requiring TORC for their transcriptional activation, such as steroidogenic acute regulatory protein and cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme (33). The demonstration by Western blot and immunofluorescence that staurosporine induced TORC translocation to the nucleus in 4B cells suggests that SIK mediates the retention of TORC in an inactive state in the cytoplasm. The concomitant activation of basal CRH promoter activity supports a role of SIK as a repressor of CRH transcription. The ability of staurosporine to induce parallel increases in TORC2 translocation to the nucleus and levels of CRH hnRNA in primary hypothalamic neuronal cultures, in conjunction with the temporal pattern of SIK induction in the dorsomedial PVN, strongly suggests that SIK represses basal CRH transcription by retaining TORC in the cytoplasm. Because staurosporine inhibits protein kinase activity by competing with the ATP binding site, it is likely that it suppresses both SIK1 and SIK2. At high concentrations staurosporine is a nonspecific kinase inhibitor, affecting a number of kinases including protein kinase C, calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase, and calcium signaling (34, 35). Although at the concentrations used (10 nm), staurosporine does not inhibit calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase (36), it is not possible to rule out that inhibition of protein kinase C and other pathways could contribute to the effects observed on CRH transcription.

The predominant expression and high inducibility of SIK1 vs. SIK2 in the PVN as well as in 4B cells and primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons led us to hypothesize that SIK1 was the major type involved in the regulation of the CRH neuron. However, it was unexpected that SIK1 shRNA had no effect on TORC translocation or on CRH promoter activity, despite effectively suppressing induction of SIK1 mRNA and protein. Although the increases in SIK2 mRNA levels after suppression of SIK1 could be responsible for the ineffectiveness of SIK1 blockade, the inability of SIK1 to compensate for the absence of SIK2 suggests that SIK2 is actually responsible for sequestering TORC in the cytoplasm in an inactive phosphorylated state in basal conditions. This possibility is consistent with the presence of SIK2 protein in the cytoplasm of 4B cells in basal conditions shown by the present experiments. On the other hand, the fact that SIK1 mRNA and protein are low in basal conditions and increase after stimulation raises the interesting possibility that induction of SIK1 is part of the mechanism of limiting transcription by phosphorylating TORC in the nucleus and causing its inactivation and release from the CRH promoter. Unfortunately, combined knockdown of SIK1 and SIK2 could not be tested because of problems with cell viability when transfecting the large amounts of DNA required to reduce SIK mRNA. Future studies will be needed to fully elucidate the specific roles of SIK1 and SIK2 in the regulation of CRH transcription.

Overall, these studies provide in vivo and in vitro evidence for the involvement of SIK1 and SIK2 in the regulation of CRH transcription. The inverse relationship between SIK expression and TORC2 trafficking and CRH transcription strongly suggest that SIK represses CRH transcription by preventing TORC translocation to the nucleus. Although the SIK overexpression experiments indicate that both SIK1 and SIK2 can inhibit TORC translocation and CRH transcription, the lack of effect of SIK1 blockade and the fact that increases in SIK1 due to SIK2 knockdown cannot compensate for the lack of SIK2 suggest that SIK2 is responsible for maintaining phosphorylated TORC in the cytoplasm. The temporal pattern of induction of SIK1, reaching a maximum at the time when TORC content in the nucleus and CRH transcription declines, suggests that SIK1 induction and activation could be involved in limiting transcriptional responses of the CRH gene. The study provides strong evidence that regulation of the activity of both SIK1 and SIK2 could serve as a control mechanism for rapid activation and inactivation of CRH transcription by regulating TORC activity and accessibility of the coactivator TORC to the CRH promoter.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mark Montminy (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA) for providing the expression vectors for SIK1 and SIK2 shRNA.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (to G.A.), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS029728 (to A.G.W.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- CRE

- cAMP-responsive element

- CREB

- cAMP response element binding protein

- hn

- heteronuclear

- LKB1

- liver kinase B1

- mpd

- medial parvicellular part

- PMA

- phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate

- PVN

- paraventricular nucleus

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- SIK

- salt-inducible kinase

- TORC

- transducer of regulated CREB activity.

References

- 1. Bale TL, Vale WW. 2004. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 44:525–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vale W, Rivier C, Brown MR, Spiess J, Koob G, Swanson L, Bilezikjian L, Bloom F, Rivier J. 1983. Chemical and biological characterization of corticotropin releasing factor. Recent Prog Horm Res 39:245–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berrettini WH, Oxenstierna G, Sedvall Gr, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Gold PW, Rubinow DR, Goldin LR. 1988. Characteristics of cerebrospinal fluid neuropeptides relevant to clinical research. Psychiatry Res 25:349–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heuser I, Bissette G, Dettling M, Schweiger U, Gotthardt U, Schmider J, Lammers CH, Nemeroff CB, Holsboer F. 1998. Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of corticotropin-releasing hormone, vasopressin, and somatostatin in depressed patients and healthy controls: response to amitriptyline treatment. Depress Anxiety 8:71–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holsboer F, Ising M. 2008. Central CRH system in depression and anxiety—evidence from clinical studies with CRH1 receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol 583:350–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nemeroff CB, Bissette G, Akil H, Fink M. 1991. Neuropeptide concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of depressed patients treated with electroconvulsive therapy. Corticotrophin-releasing factor, β-endorphin and somatostatin. Br J Psychiatry 158:59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Watts AG, Sanchez-Watts G. 2002. Interactions between heterotypic stressors and corticosterone reveal integrative mechanisms for controlling corticotropin-releasing hormone gene expression in the rat paraventricular nucleus. J Neurosci 22:6282–6289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guardiola-Diaz HM, Boswell C, Seasholtz AF. 1994. The cAMP-responsive element in the corticotropin-releasing hormone gene mediates transcriptional regulation by depolarization. J Biol Chem 269:14784–14791 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. King BR, Nicholson RC. 2007. Advances in understanding corticotrophin-releasing hormone gene expression. Front Biosci 12:581–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu Y, Kamitakahara A, Kim AJ, Aguilera G. 2008. Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate responsive element binding protein phosphorylation is required but not sufficient for activation of corticotropin-releasing hormone transcription. Endocrinology 149:3512–3520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nikodemova M, Kasckow J, Liu H, Manganiello V, Aguilera G. 2003. Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone promoter activity in AtT-20 cells and in a transformed hypothalamic cell line. Endocrinology 144:1292–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wölfl S, Martinez C, Majzoub JA. 1999. Inducible binding of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP)-responsive element binding protein (CREB) to a cAMP-responsive promoter in vivo. Mol Endocrinol 13:659–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu Y, Knobloch HS, Grinevich V, Aguilera G. 2011. Stress induces nuclear translocation of the CREB co-activator, transducer of regulated CREB activity (TORC) in corticotropin releasing hormone neurons. J Neuroendocrinol 23:216–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu Y, Coello AG, Grinevich V, Aguilera G. 2010. Involvement of transducer of regulated cAMP response element-binding protein activity on corticotropin releasing hormone transcription. Endocrinology 151:1109–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Conkright MD, Canettieri G, Screaton R, Guzman E, Miraglia L, Hogenesch JB, Montminy M. 2003. TORCs: transducers of regulated CREB activity. Mol Cell 12:413–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takemori H, Kajimura J, Okamoto M. 2007. TORC-SIK cascade regulates CREB activity through the basic leucine zipper domain. FEBS J 274:3202–3209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Takemori H, Okamoto M. 2008. Regulation of CREB-mediated gene expression by salt inducible kinase. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 108:287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bittinger MA, McWhinnie E, Meltzer J, Iourgenko V, Latario B, Liu X, Chen CH, Song C, Garza D, Labow M. 2004. Activation of cAMP response element-mediated gene expression by regulated nuclear transport of TORC proteins. Curr Biol 14:2156–2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Z, Takemori H, Halder SK, Nonaka Y, Okamoto M. 1999. Cloning of a novel kinase (SIK) of the SNF1/AMPK family from high salt diet-treated rat adrenal. FEBS Lett 453:135–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Katoh Y, Takemori H, Horike N, Doi J, Muraoka M, Min L, Okamoto M. 2004. Salt-inducible kinase (SIK) isoforms: their involvement in steroidogenesis and adipogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 217:109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Katoh Y, Takemori H, Min L, Muraoka M, Doi J, Horike N, Okamoto M. 2004. Salt-inducible kinase-1 represses cAMP response element-binding protein activity both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm. Eur J Biochem 271:4307–4319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Watts AG, Tanimura S, Sanchez-Watts G. 2004. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin gene transcription in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of unstressed rats: daily rhythms and their interactions with corticosterone. Endocrinology 145:529–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang B, Goode J, Best J, Meltzer J, Schilman PE, Chen J, Garza D, Thomas JB, Montminy M. 2008. The insulin-regulated CREB coactivator TORC promotes stress resistance in Drosophila. Cell Metab 7:434–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Katoh Y, Takemori H, Lin XZ, Tamura M, Muraoka M, Satoh T, Tsuchiya Y, Min L, Doi J, Miyauchi A, Witters LA, Nakamura H, Okamoto M. 2006. Silencing the constitutive active transcription factor CREB by the LKB1-SIK signaling cascade. FEBS J 273:2730–2748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanyo R, Price DM, Chik CL, Ho AK. 2009. Salt-Inducible kinase 1 in the rat pinealocyte: adrenergic regulation and role in arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase gene transcription. Endocrinology 150:4221–4230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu Y, Watts AG, Sanchez-Watts G, Aguilera G. Stimulus- and brain region-specific regulation of salt inducible kinase and AMP activated protein kinase in the rat hypothalamus. Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, 2010, Abstract 792.1 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koo SH, Flechner L, Qi L, Zhang X, Screaton RA, Jeffries S, Hedrick S, Xu W, Boussouar F, Brindle P, Takemori H, Montminy M. 2005. The CREB coactivator TORC2 is a key regulator of fasting glucose metabolism. Nature 437:1109–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kageyama K, Suda T. 2009. Regulatory mechanisms underlying corticotropin-releasing factor gene expression in the hypothalamus. Endocr J 56:335–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu Y, Aguilera G. 2009. Cyclic AMP inducible early repressor mediates the termination of corticotropin releasing hormone transcription in hypothalamic neurons. Cell Mol Neurobiol 29:1275–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hashimoto YK, Satoh T, Okamoto M, Takemori H. 2008. Importance of autophosphorylation at Ser186 in the A-loop of salt inducible kinase 1 for its sustained kinase activity. J Cell Biochem 104:1724–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lizcano JM, Göransson O, Toth R, Deak M, Morrice NA, Boudeau J, Hawley SA, Udd L, Mäkel ä TP, Hardie DG, Alessi DR. 2004. LKB1 is a master kinase that activates 13 kinases of the AMPK subfamily, including MARK/PAR-1. EMBO J 23:833–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bright NJ, Thornton C, Carling D. 2009. The regulation and function of mammalian AMPK-related kinases. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 196:15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takemori H, Kanematsu M, Kajimura J, Hatano O, Katoh Y, Lin XZ, Min L, Yamazaki T, Doi J, Okamoto M. 2007. Dephosphorylation of TORC initiates expression of the StAR gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol 265–266:196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rüegg UT, Burgess GM. 1989. Staurosporine, K-252 and UCN-01: potent but nonspecific inhibitors of protein kinases. Trends Pharmacol Sci 10:218–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yanagihara N, Tachikawa E, Izumi F, Yasugawa S, Yamamoto H, Miyamoto E. 1991. Staurosporine: an effective inhibitor for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurochem 56:294–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu Y, Randall WR, Schneider MF. 2005. Activity-dependent and -independent nuclear fluxes of HDAC4 mediated by different kinases in adult skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol 168:887–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]