Abstract

Background:

Diabetes mellitus is an emerging global health problem. It is a chronic, noncommunicable, and expensive public health disease.

Aims and Objectives:

To determine the prevalence and the risk factors of type 2 diabetes mellitus among the adult population of Puducherry, South India.

Materials and Methods:

This was a population-based cross-sectional study carried out during 1st May 2007–30th November 2007 in the rural and urban field practice area of Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute, Puducherry. Simple random sampling technique was used for the selection of 1370 adult 20 years of age and above. Main outcome measures were the assessment of the prevalence of prevalence and correlates of diabetes among the adult population. Predesigned and pretested questionnaire was used to elicit the information on family and individual sociodemographic variables. Height, weight, waist, and hip circumference, blood pressure was measured and venous blood was also collected to measure fasting blood glucose, blood cholesterol.

Results:

Overall, 8.47% study subjects were diagnosed as diabetic. The univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the important correlates of diabetes mellitus were age, blood cholesterol, and family history of diabetes. The findings were found to be statistically significant.

Conclusions:

In our study we observed that adults having increased age, hypercholesterolemia, and family history of diabetes mellitus are more likely to develop diabetes mellitus.

KEY WORDS: Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose level, India

Diabetes mellitus is a global epidemic in the new millennium. The World Health Organization (WHO) has observed an apparent epidemic of diabetes that is strongly related to lifestyle and economic change to exceed 200 million over the next decade; mostly with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and all are at risk of the development of complications.[1] T2DM is a diverse group of diseases developing insidiously and portrayed by chronic hyperglycaemia, resulting from a assortment of environmental and genetic risk factors.[2] Other correlates are population explosion, increasing geriatric population, cost of industrial growth, urban trend, liking of high fat containing junk foods, inactive living, and obesity.[3]

For intervention of this colossal public health and economic burden created by the pandemic of T2DM, earliest clinical concern in the prediabetes phase to prevent complications seems to be the most rational step. Sensible lifestyle changes have been shown to notably trim down the risk of progression in individuals with impaired fasting glucose (IFG). Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) results in continued preventive benefit even after stoppage of structured counseling. The age adjusted death rates in T2DM are 1.5%-2.5% times higher than general population.[4–6] Recent European study noted that population groups with more deprived socioeconomic position (SEP) have increased incidence, prevalence and mortality due to T2DM. The scale and implication of the associations may differ with greater effects on women. Recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed that augmented risk of T2DM was linked with lower educational level, occupation and income even in people with low SEP in high-, middle-, and low-income countries.[7,8]

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is still the best diagnostic test for T2DM, though expensive, inconvenient and has weak reproducibility. Fasting plasma glucose would overlook people with IGT; glycated hemoglobin does not require fasting, and may be the best compromise.[9] Population level prevention of T2DM should be based on the risk groups to prevent macroangiopathic changes.[10] The Canadian study showed that the age-adjusted and sex-adjusted diabetes prevalence increased by 69 percent, from 5.2 percent in 1995 to 8.8 percent in 2005; prevalence increased by 27 percent from 6.9 percent in 2000 to 8.8 percent in 2005; higher in age 50 years or older.[11]

The study was undertaken to determine the prevalence and the risk factors of type 2 diabetes mellitus among the adult population of Puducherry, South India.

Materials and Methods

Settings and design

Population-based cross-sectional study was carried out in the rural and urban field practices area of tertiary care teaching institute at Puducherry during 1st May 2007–30th November 2007 among 1370 adult 20 years of age and above.

Sampling design

Prevalence rate of diabetes in India (Urban and Rural) among adults (20 year and above) is 62.47 per thousand as calculated by the experts at WHO for use in the national levels in India.[1] Considering this prevalence of diabetes mellitus with 5% alpha error, 20% absolute allowable error, 1370 sample size was calculated. This sample was selected by simple random sampling from the population in the field practice area. All eligible individuals were identified from electoral roll of election commission of India. Two separate lists of eligible, one for urban area and another for rural area were prepared; 685 subjects 20 years and above were selected each from rural and urban area by random sampling.

Study instrument

The data collection tool used for the study was an interview schedule that was developed at the Institute with the assistance from the faculty members and other experts. This predesigned and pretested questionnaire contained questions relating to the information on family characteristics such as residence, type of family, family history of diabetes mellitus, family history of chronic disease, income and personal characteristics such as age, sex, education, occupation, and type of food, dietary habit. By initial translation, back-translation, retranslation followed by pilot study the questionnaire was custom-made for the study. The pilot study was carried out at the institute among general subjects following which some of the questions from the interview schedule were modified. Blood pressure with the anthropometric measurements was done and venous blood samples were collected for fasting blood glucose.

Data collection procedure

The health workers informed and motivated the families to participate in the study; no non-response was reported. All the participants were explained about the purpose of the study and were ensured strict confidentiality, and then informed consent was taken from each of them before the total procedure. The participants were given the options not to participate in the study if they wanted.

Variables

Dependent variable: Diabetes (T2DM) -- Blood examination was carried out in the biochemistry departmental laboratory of tertiary care institute, Puducherry with the diagnostic criteria of the fasting venous blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dl were classified as case of T2DM.[12]

Independent variables: Blood pressure and the anthropometric measurements such as body weight, height, waist, and hip circumference. Data regarding family and personal characteristics were recorded by personal interview using predesigned and pretested questionnaire. Body weight was measured (to the nearest 0.5 kg) in the standing motionless on the bath room scale with feet 15 cm apart, and weight equally distributed on each leg. Height was measured (to the nearest 0.5 cm) by stadeometer in standing position with closed feet, holding their breath in full inspiration and Frankfurt line of vision. Waist and hip circumference was measured by flexible nonstretchable measuring tape in standing.

Statistical analysis used

The collected data were thoroughly screened and entered into MS-Excel spread sheets and analysis was carried out. Proportion of adult person with diabetes mellitus was presented as percentage. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated for each categorical risk factors. Backward LR method was used to perform multiple logistic regressions, where presence of diabetes mellitus was used as dependent variable while others as independent variables and P <0.05 as statistical significance.

Results

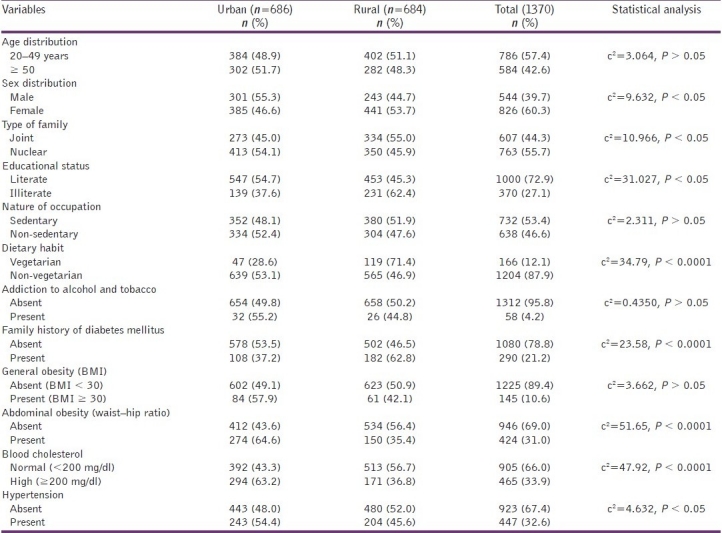

Out of 1370 adult 20 years of age and above, 544 (39.7%) were males and 826 (60.3%) were females. Urban and rural participants were comparable representing 50.07% in urban settings. Majority of study participants (57.4%) were in the 20-49 years age. Majority of the study population were from nuclear families (55.7%), were literate (73%), had a sedentary work level at occupational arena (53.4%), were nonvegetarian (87.9%),without any history of intake of tobacco and alcohol (95.8%). Majority of the respondents did not give any family history of diabetes (79.4%); had a BMI of less than 30 (89.4%), with no abdominal obesity (69%), having a normal blood cholesterol level (66%) and were nonhypertensive (67.4%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the study participants at Puducherry

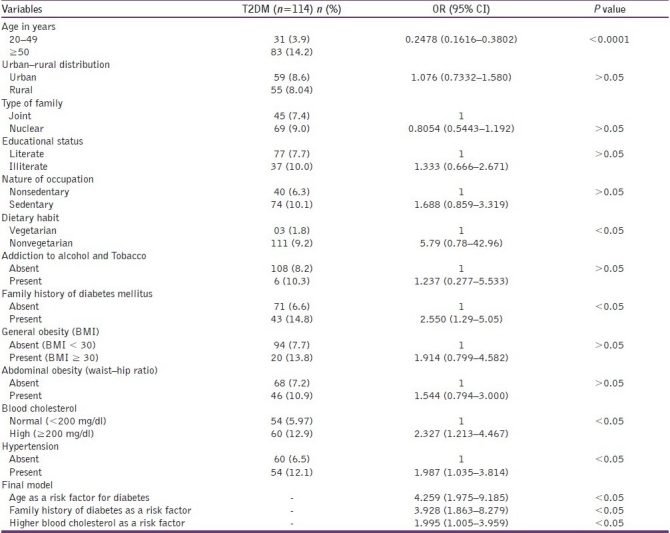

The proportion of diabetes mellitus was higher (14.2%) in persons aged ≥50 years than in persons aged between 20 and 49 years, the difference was statistically significant. Diabetes were seen to be more prevalent among those from nuclear families (9%), illiterate (10.0%), having sedentary occupation (10.1%), were nonvegetarian (9.2%), nonalcoholic, and nonsmokers (10.3%), having family history of diabetes mellitus (14.8%), obesity (13.8%), with higher waist–hip ratio (10.9%). Diabetes was associated with high blood cholesterol (12.9%) and with 12.1% of hypertensive participants. Prevalence of diabetes was significantly associated with diabetes in the family, obesity, increased waist–hip ratio, blood cholesterol, and hypertension Overall, 116 (8.47%) study subjects were had fasting venous blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dl. Magnitude of persons with fasting venous blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dl was almost same in both urban (8.6%) and rural (8.04%) area. In the multivariate logistic regression significant risk factors were: age 50 years and above, family history, and higher total blood cholesterol level. [Table 2].

Table 2.

Prevalence of T2DM and association between T2DM and each risk factor (OR and 95% confidence intervals) among study participants

Discussion

Our study reflects the correlates of diabetes among 1370 adult 20 years of age and above in Puducherry during 2007.The proportion of diabetes mellitus was higher (14.2%) in persons aged ≥50 years than in persons aged between 20 and 49 years, the difference was statistically significant. Diabetes were seen to be more prevalent among those from nuclear families (9%), illiterate (10.0%), having sedentary occupation (10.1%), were nonvegetarian (9.2%), nonalcoholic, and nonsmokers (10.3%), having family history of diabetes mellitus (14.8%), obesity (13.8%), with higher waist–hip ratio (10.9%). Diabetes was associated with high blood cholesterol (12.9%) and with 12.1% of hypertensive participants. Prevalence of diabetes was significantly associated with diabetes in the family, obesity, increased waist–hip ratio, blood cholesterol, and hypertension Overall, 116 (8.47%) study subjects were had fasting venous blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dl. Magnitude of persons with fasting venous blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dl was almost same in both urban (8.6%) and rural (8.04%) area. In the multivariate logistic regression, significant risk factors were: age 50 years and above, family history, and higher total blood cholesterol level.

Comparable data were seen in Lucknow 9.1%, and 1.4% in Madurai in the population above 30 years of age.[8,13]

Our study shows diabetes mellitus rate increases as age increases. Similar trend reported by Ramaiya et al and Ramachandran et al.[13,14]

Magnitude of diabetes mellitus was more among males than females in this study. Similar findings were reported by various researchers in India regarding female preponderance in Indian diabetics.[11,13,14] Researchers in Tanzania also reported similar trends in men and women.[15]

Sedentary habit showed weak positive association in our study, while Ramaiya et al in Mauritius and Swai et al among Indian Muslim of Tanzania reported a positive association.[13,15]

Non-vegetarian dietary habit showed weak positive association in this study, while other researchers reported that prevalence of diabetes mellitus was more in vegetarians.[11,13]

In our study, blood cholesterol level showed weak positive association with diabetes. WHO report put in the picture that a high saturated fat intake and high proportion of saturated fatty acids in serum lipid was associated with higher prevalence T2DM.[16–18]

In this study, we observed that hypertension and family history of diabetes mellitus had a probability of having increased risk of diabetes mellitus. This trend was significantly higher among adults aged 50 years and above, and in those whose blood cholesterol and blood pressure were higher than normal with family history of diabetes mellitus. Other researchers in the field of T2DM also reported comparable positive associations.[13,19]

The participants in our study did not show any association between T2DM with residential area, education, income, addiction, general obesity (BMI) and abdominal obesity (waist–hip ratio). WHO reported higher prevalence in urban population though these associations were not reported uniformly in other studies.[5] There was observance of wide urban--rural difference in the prevalence of diabetes in Indian population in numerous studies.[13,20,21]

Bjorntorp reported association of T2DM with intra-abdominal fat.[22] A Polish study evaluated the prevalence of diabetes, obesity and lipid disorders in a well-defined urban population aged 35 and over; overall prevalence was 15.7 percent. Excessive body weight was noted in 39.9 percent, and obesity 31.0 percent. High prevalence of recognized and unidentified diabetes together with other metabolic disorders was strikingly high in adult urban population.[23]

In a recent study in China, prevalence of T2DM and IFG were 5.5 percent and 3.3 percent, respectively; 42.3 percent were newly diagnosed. The prevalence of T2DM and IFG increased with age, a positive family history, and associated with obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia.[24]

Recent retrospective data analysis in Pondicherry from family records showed a prevalence of known diabetes of 5.6 percent (5.31% in males and 6.1% in females). In the age group of 20 years and above, the prevalence was 8.2 percent whereas the age-specific prevalence was above 20 percent above the age of 50 years. The youngest diabetic reported was an 11-month-old male child with T2DM. In the age groups 20 to 29 and 50 to 59 years, there were more females with T2DM.[25]

Epidemiological researchers in India had a pragmatic assumption that the Indian population is a homogeneous community. Yet reports of the studies have noted that there is considerable intercommunity variations in T2DM and the risk factors were linked to genetic, dietary, socioeconomic, and lifestyle differences. Multicentric efforts on T2DM among Indian subcommunities are necessary to validate and broaden these observational findings and search the genetic basis of T2DM with the assumption of heterogeneity.[26] The North-eastern Indian study, on the other hand, highlighted that urban Indians from any geographical location of the country have a higher probability of T2DM; the interstate differences in the prevalence were minor. There may be some universal etiological factors, namely presence of high familial aggregation and the environmental influences associated with urbanization.[27]

The age-adjusted prevalence of T2DM was 8.2 percent in the urban and 2.4 percent in the rural populations with 8.4 percent in urban men and 7.9 percent in urban women. Age, BMI, and waist--hip ratios showed positive association with T2DM in both populations. Upper body adiposity and BMI were positive risk factors in the leaner population with low BMI in the rural population.[28] In another related study, the non-obese South Indian population, android waist–hip ratio was noted to be greater risk factor for T2DM than general obesity.[29,30] The prevalence of T2DM and IGT was higher among urban working women in Orissa that was mounting with increase age; obesity played a major role. Numerous long- and short-term steps were suggested for promotion of healthy life style to prevent T2DM with its dreaded complications.[31]

The strength of the study was that it was a population based cross-sectional study to find the prevalence of T2DM among adults in both urban and rural area. Bias was taken care of by random sampling. The limitation of the study was that, we could not include in the study of the prevalence of T2DM among adolescents. Further, the oral glucose tolerance test could not be included in our methods. In future directions of our study, we noted the all the recent epidemiologic studies, T2DM had increased dramatically throughout the world including IFG over the past few decades though a large proportion of cases go undiagnosed. We hope to find out nationally representative data base on the prevalence of T2DM in our country by multicentric studies. The key factor to prevent diabetes mellitus is that we have to generate awareness among our peers, public health experts, health services researchers, healthcare providers and planners to consider the higher prevalence and associated risk factors of diabetes mellitus as a public health problem in the developing countries such as “diabetic capital” India.

To sum up, we observed that the prevalence of T2DM was 8.47 percent. Moreover, adults with the increasing age, hypercholesterolemia and family history of diabetes mellitus are more likely to develop diabetes mellitus. These findings suggest that his could lay the foundation for the introduction of primary health care with community participation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1. [Retrieved on 2007 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.whoindia.org/SCN/AssBOD/06-Diabetes.pdf .

- 2.Park K. Epidemiology of chronic non-communicable diseases and condition in Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 20th ed. Vol. 6. Jabalpur, India: Banarsidas Bhanot; 2009. p. 341. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grover S, Avasthi S, Bhansali A, Chakrabarthi S, Kulhara P. Cost of ambulatory care of diabetes mellitus: A study from north India. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:391–5. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.024299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenstock J. Reflecting on type 2 diabetes prevention: More questions than answers! Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9(Suppl 1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. (1-149).WHO Tech Rep Ser 916. 2003:i–viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH. Global burden of diabetes, 1995-2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projection. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1414–31. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espelt A, Arriola L, Borrell C, Larrañaga I, Sandín M, Escolar-Pujolar A. Socioeconomic position and type 2 diabetes mellitus in Europe 1999-2009: A panorama of inequalities. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2011;7:148–58. doi: 10.2174/157339911795843131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agardh E, Allebeck P, Hallqvist J, Moradi T, Sidorchuk A. Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol (2011) first published online February 19. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waugh N, Scotland G, McNamee P, Gillett M, Brennan A, Goyder E, et al. Screening for type 2 diabetes: Literature review and economic modelling. (ix-xi, 1-125).Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta11170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wierusz-Wysocka B, Zozulinska D, Knast B, Pisarczyk-Wiza D. Appearance of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in the population of professionally active people in the urban areas. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2001;106:815–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipscombe LL, Hux JE. Trends in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality in Ontario, Canada 1995-2005: A population-based study. Lancet. 2007;369:750–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications. World Health Organisation. 1999. [Last retrieved on 2011 Feb 21]. Retrieved on 30 November 2010. Available from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_NCD_NCS_99.2.pdf .

- 13.Ramaiya KL, Kodali VRR, Alberti KGMM. Epidemiology of diabetes in Asians of the Indian sub-continent. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 1991;2:15–36. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramachandran A, Jali MV, Mohan V, Snehalatha C, Viswanathan M. High prevalence of diabetes in an urban population in south India. BMJ. 1988;297:587–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6648.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swai AB, McLarty DG, Sherrif F, Chuwa LM, Maro E, Lukmanji Z, et al. Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in an Asian community in Tanzania. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1990;8:227–34. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(90)90121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO Expert Committee on Diabetes Mellitus: Second report. WHO Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1980;646:1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diabetes mellitus. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1985;727:1–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health situation in the south-east Asia Region, 1998-2000. New Delhi: Regional office for South-East Asia, WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viswanathan M, Mohan V, Snehalatha C, Ramachandran A. High prevalence of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes among the offspring of conjugal type 2 diabetic parents in India. Diabetologia. 1985;28:907–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00703134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Dharmaraj D, Vishwanathan M. Prevalence of glucose intolerance in Asian Indians: Urban-rural difference and significance of upper body adiposity. Diabetes care. 1992;15:1348–55. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.10.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King H, Rewers M. Global estimates for prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in adults. WHO Ad Hoc Diabetes Reporting Group. Diabetes care. 1993;16:157–77. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Björntorp P. Abdominal obesity and the development of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1988;4:615–22. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610040607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drzewoski J, Saryusz-Wolska M, Czupryniak L. Type II diabetes mellitus and selected metabolic disorders in urban population aged over 35 years. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2001;106:787–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Qiu Q, Tan LL, Liu T, Deng XQ, Chen YM, et al. Prevalence and determinants of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose among urban community-dwelling adults in Guangzhou, China. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35:378–84. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purty AJ, Vedapriya DR, Bazroy J, Gupta S, Cherian J, Vishwanathan M. Prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in an urban area of Puducherry, India: Time for preventive action. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2009;29:6–11. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.50708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramaiya KL, Swai AB, McLarty DG, Bhopal RS, Alberti KG. Prevalences of diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Hindu Indian subcommunities in Tanzania. BMJ. 1991;303:271–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6797.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah SK, Saikia M, Burman NN, Snehalatha C, Ramachandran A. High prevalence of type 2 diabetes in urban population in north eastern India. Int J Diab Dev Ctries. 1999;19:144–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramachandran A. Epidemiology of Diabetes in Indians. Int J Diab Dev Ctries. 1993;13:65–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misra A, Kathpalia R, Lall SB, Peshin S. Hyperinsulinemia in non-obese, non-diabetic subjects with isolated systolic hypertension. Indian Heart J. 1998;50:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cassell PG, Neverova M, Janmohamed S, Uwakwe N, Qureshi A, McCarthy MI, et al. An un-coupling protine-2 gene variant associated with a raised body mass index but not Type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 1999;42:688–92. doi: 10.1007/s001250051216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malini DS, Sahu A, Mohapatro S, Tripathy R. Assessment of Risk Factors for Development of Type-II Diabetes Mellitus Among Working Women in Berhampur, Orissa. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:232–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.55290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]