Abstract

Background:

One of the hallmarks of modern medicine is the improving management of chronic health conditions. Long-term control of chronic disease entails increasing utilization of multiple medications and resultant polypharmacy. The goal of this study is to improve our understanding of the impact of polypharmacy on outcomes in trauma patients 45 years and older.

Materials and Methods:

Patients of age ≥45 years were identified from a Level I trauma center institutional registry. Detailed review of patient records included the following variables: Home medications, comorbid conditions, injury severity score (ISS), Glasgow coma scale (GCS), morbidity, mortality, hospital length of stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) LOS, functional outcome measures (FOM), and discharge destination. Polypharmacy was defined by the number of medications: 0–4 (minor), 5–9 (major), or ≥10 (severe). Age- and ISS-adjusted analysis of variance and multivariate analyses were performed for these groups. Comorbidity–polypharmacy score (CPS) was defined as the number of pre-admission medications plus comorbidities. Statistical significance was set at alpha = 0.05.

Results:

A total of 323 patients were examined (mean age 62.3 years, 56.1% males, median ISS 9). Study patients were using an average of 4.74 pre-injury medications, with the number of medications per patient increasing from 3.39 for the 45–54 years age group to 5.68 for the 75+ year age group. Age- and ISS-adjusted mortality was similar in the three polypharmacy groups. In multivariate analysis only age and ISS were independently predictive of mortality. Increasing polypharmacy was associated with more comorbidities, lower arrival GCS, more complications, and lower FOM scores for self-feeding and expression-communication. In addition, hospital and ICU LOS were longer for patients with severe polypharmacy. Multivariate analysis shows age, female gender, total number of injuries, number of complications, and CPS are independently associated with discharge to a facility (all, P < 0.02).

Conclusion:

Over 40% of trauma patients 45 years and older were receiving 5 or more medications at the time of their injury. Although these patients do not appear to have higher mortality, they are at increased risk for complications, lower functional outcomes, and longer hospital and intensive care stays. CPS may be useful when quantifying the severity of associated comorbid conditions in the context of traumatic injury and warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Comorbid conditions, outcome prediction, polypharmacy, trauma outcomes

INTRODUCTION

One of the hallmarks of modern medicine is the increasing prevalence and improving management of chronic health conditions.[1–3] Intimately associated with the long-term control of chronic disease is the increasing utilization of multiple medications and resultant polypharmacy.[4–6] Trauma patients are significantly more likely to experience adverse reactions to medication than non-trauma patients.[7,8] Despite this, very little has been published on the relationship between polypharmacy and outcomes in the trauma population and most of the published studies continue to focus on risks associated with individual agents as opposed to simultaneous use of multiple medications.[7,9–12] This study was designed to better characterize the impact of polypharmacy on trauma patients who are 45 years and older. We hypothesized that polypharmacy would correlate with trauma patient outcomes. Our aim was to determine if increasing polypharmacy would predict morbidity, mortality, and resource utilization in older trauma patients. Our secondary goal was to improve our understanding of both the incidence and patterns of polypharmacy in the study population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study patients were identified from an American College of Surgeons verified level I trauma center institutional database. Based on previously published observations, we chose to include patients aged 45 years and older. This age cut-off represents best estimate of the youngest patient group with noticeable increase in the number of chronic health conditions commonly treated with long-term “maintenance” pharmacologic therapy.[1,6] Exclusion criteria included prisoners, pregnant patients, and injured patients who died before leaving the emergency department resuscitation area. There were only six patients excluded (1.9% of the total study sample) based on the latter exclusion criterion, all of whom had insufficient or missing comorbidity or medication data and would otherwise be excluded from key univariate or multivariate analyses.

Detailed review of medical records was performed, including examination of the following variables: Home medications, comorbid conditions, injury severity score (ISS), Glasgow coma scale (GCS), morbidity and mortality, hospital length of stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) LOS, functional outcome measures (FOM), and discharge destination.[1,4,13] Based on pre-existing criteria, study patients were grouped by the number of medications: 0–4 (minor polypharmacy), 5–9 (major polypharmacy), or ≥10 (severe polypharmacy).[1] FOM were scored from 1 (lowest) to 4 (highest) for three areas: (a) expression-communication; (b) locomotion; and (c) self-feeding.[13] Comorbidity–polypharmacy score (CPS) was defined as the total number of pre-admission medications plus the total number of comorbidities for each patient.

In accordance with our established institutional procedures, detailed medication reconciliation is performed routinely for injured patients. All patients admitted to The Ohio State University Health System have an allergy and medication history collected and recorded upon admission (with rare exceptions where such history is not immediately obtainable). The list of medications that a patient has been taking prior to admission is designated as the “arrival medication list”. Staff authorized to enter the arrival medication list include: Licensed/registered nurses, nurse practitioners, attending physicians, fellow/resident physicians, medical students, pharmacists, and physician assistants. For patients arriving in the Emergency Department, the arrival medication list is entered into the Emergency Department data system (IBEX, IBEX/PICIS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For inpatients, the arrival medication list is entered into the computerized order entry system (CAPI), with the Emergency Department list available for reference from CAPI. For patients admitted from home, the arrival medication list is compiled from the medications the patient was taking at home. For patients transferred from another facility, the arrival medication list comprises both the medications the patient was receiving at the transferring facility and the medications the patient was taking at home. The process is further augmented by periodic reviews and verifications of medication data. For the purposes of this study, only the original home medication list (and not the list of medications present on transfer) was utilized to determine polypharmacy and the CPS.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics, including Kolmogorov–Smirnov testing for normality. Non-normally distributed variables (ISS, number of injuries) were reported using median, range, inter-quartile range, and further analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test for multi-group comparisons. Normally distributed variables were reported as mean ± SD (or SEM) and tested using analysis-of-variance (ANOVA). Additional adjustments for age and ISS were made when comparing polypharmacy groups for differences in key outcome parameters. Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square or Fisher's exact test. Statistical significance was set at alpha = 0.05. Subsequent multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed utilizing variables with pre-determined statistical significance of P < 0.20 on initial univariate analyses. PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software package was utilized. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

RESULTS

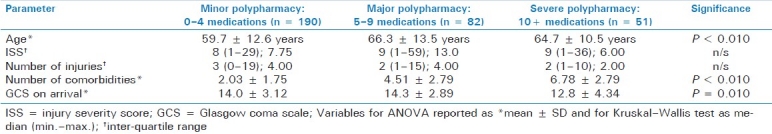

A total of 323 consecutive trauma patients, 45 years and older, were identified. The mean age of the study group was 62.3 ± 12.9 years. Males represented 56.1% of the patient sample. Median ISS was 9 (range 1–75, interquartile range 9). Detailed demographic information, grouped by polypharmacy ranges (as defined above), is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative demographics of the three polypharmacy groups (minor/major/severe)

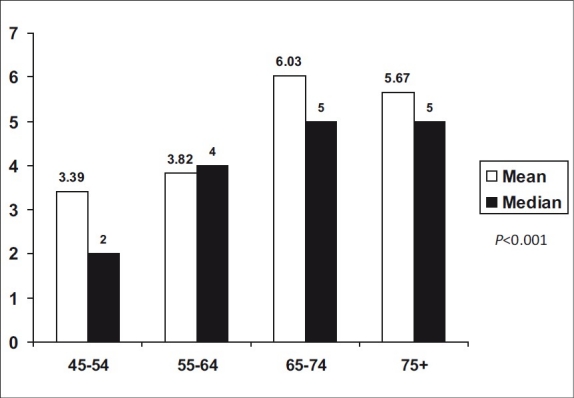

Polypharmacy was prevalent in the study group, with over 40% of patients taking at least 5 medications. The mean number of medications per patient was 4.74 ± 4.34 (median 4, range 0–19). The average severity of polypharmacy significantly increased with age [Figure 1]. In fact, the number of medications per patient approximately doubles as one proceeds from the 45–54 years age range (mean 3.39/median 2 medications) to the 75+ years age group (mean 5.67/median 5 medications)(P < 0.001). Not surprisingly, there is a statistically significant correlation of intermediate magnitude between the number of medications and the number of comorbid conditions (r = 0.68, P < 0.010). In addition, patients in the higher polypharmacy groups had lower arrival GCS, more overall complications, and lower discharge FOM scores for self-feeding and expression-communication [Tables 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Relationship between patient age and polypharmacy. Patients are grouped by age (x-axis) with corresponding mean (white) and median (solid black) number of pharmacologic agents per patient

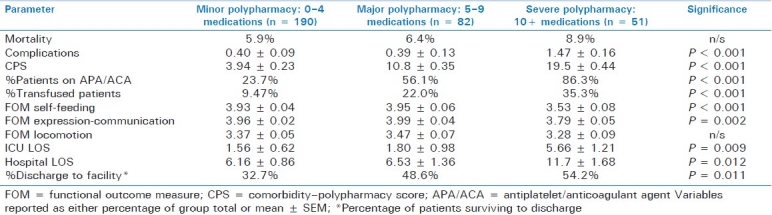

Table 2.

Age- and ISS-adjusted outcome variables grouped by polypharmacy categories

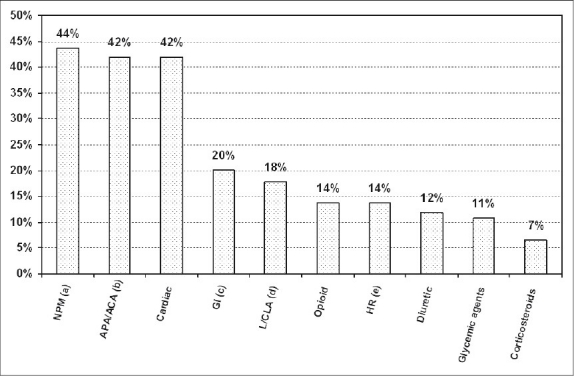

The most prevalent among different medication classes were neuro-psychiatric medications (present in 44% of patients). Antiplatelet/anticoagulant agents and cardiac non-diuretic medications were tied for the second most common type of drug in this study (each 42%). Gastrointestinal (20%), lipid/cholesterol lowering agents (18%), opioids (14%) and hormonal replacement therapies (14%) followed. Diuretics and glycemic control agents were less common [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Patterns of pharmaceutical use in this study. The ten most common medication groups in this study, listed from the most common to the least common, are as follows: NPMa = neuro-psychiatric medications – antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, antiepileptic medications, agents used for Alzheimer's disease, anti-Parkinsonian agents; APA/ACAb = antiplatelet agents/anticoagulant agents; cardiac = beta-adrenergic blockers, calcium channel blockers, antiarrhythmics, digoxin, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers; GIc = gastrointestinal agents – H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, bowel activity modulators; L/CLAd = lipid/cholesterol lowering agents; opioids; HRe = hormonal replacement – thyroid hormone, estrogen, other endocrine replacement regimens; glycemic agents – both enteral and parenteral; corticosteroids – regularly scheduled steroid therapy

Age- and ISS-adjusted mortality was similar across the three polypharmacy groups (i.e., mild, moderate, and severe) [Table 2]. In multivariate analysis, only age (OR 1.10 per each additional year) and ISS (OR 1.16 per each additional point, both P < 0.001) were found to be contributory to mortality. Neither the comorbidities, polypharmacy nor the CPS were found to significantly contribute to mortality. Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that none of the major medication sub-types (Figure 2 legend for medication class definitions) were independently associated with mortality (all, P > 0.080).

Both hospital and ICU LOS were significantly longer for patients with severe polypharmacy [Table 2]. The proportion of surviving patients who required discharge to a facility following acute hospitalization markedly increased as the degree of polypharmacy worsened (32.7% discharged to a facility among minor polypharmacy patients; 54.2% in the severe polypharmacy group, P = 0.011). In addition, multivariate analysis demonstrated that advanced age (OR 1.06 per year), female gender (OR 2.17), increasing number of injuries (OR 1.39 per each additional injury), total number of complications (OR 3.82 per complication), and CPS (OR 1.09 per point) were all independently associated with discharge to a facility (all, P < 0.020). Of note, the number of medications or the number of comorbid conditions alone were not significant predictors of discharge to a facility.

DISCUSSION

Polypharmacy is one of the defining features of the modern healthcare environment. As our ability to effectively manage chronic health conditions improves, unintended consequences of the use of multiple concurrent pharmacologic agents are becoming more apparent.[1,14] Our knowledge of the impact of polypharmacy is very limited despite the fact that the need for medication administration in the trauma population is very high and injured patients are more likely to experience adverse sequelae related to medications than non-trauma patients.[7,8] Adverse drug-related events and potentially harmful drug–drug interactions constitute majority of those undesired sequelae.[7,10,14] In addition, increasing degrees of polypharmacy may be reflective of the overall severity of the underlying comorbid conditions.[5]

Polypharmacy is increasing in prevalence – a trend that is likely to continue into the foreseeable future as the older age groups increase in both size and proportion within our population.[1] In the current study, 40% of trauma patients aged 45 and older were using 5 or more concurrent medications. Other investigators report that over 90% of patients over 65 years were taking 1 or more medications, with an average number of 4.2 medications per patient.[10] We found in our study that the number of medications increases with advancing age [Figure 1]. Patients in the 45–54 years age group used an average of 3.4 regularly scheduled medications, while patients who were 75 years and older used an average of 5.7 medications. One must also keep in mind the fact that an average hospitalization following traumatic injury is associated with the use of 5–10 new/additional medications (i.e., sedatives, antibiotics, analgesics, vasoactive agents, gastrointestinal and venous thrombosis prophylaxis), potentially predisposing the patient to even more side effects and drug–drug interactions.[7]

Although literature on polypharmacy in the trauma population is limited, it clearly points toward the dangers of concurrent use of multiple medications.[4,6,9,12] Multiple potential drug–drug interactions are possible, with a comprehensive list of such interactions previously published by Corbett and Rebuck.[7] In addition, numerous reports show that the risk of traumatic falls increases as the number of medications co-administered increases, with simultaneous use of 5 or more medications being strongly associated with risk of injury from falls.[4,12] The current study does not specifically look at the risk of injury associated with increasing medication use. However, we did note that polypharmacy was associated with lower GCS on admission, increasing hospital and intensive care LOS, as well as lower functional outcomes. Others reported that surgical patients taking a drug unrelated to the index procedure had an approximate 2.5-fold increase in risk for postoperative complications.[15]

Neuro-psychiatric agents were the most prevalent medication group in this study [Figure 2]. In general, any medication that affects the central nervous system has the potential to increase the risk of traumatic injury, from impairing an individual's ability to operate a motor vehicle to increasing the propensity for falls.[11] Combinations of various neuro-psychiatric medications may be more deleterious than single-agent therapy, where regimens involving antidepressants as one of the agents have been associated with increased risk of motor vehicle crashes and falls in the elderly.[11,16–18] Agents often involved in drug–drug interactions with antidepressants may include antipsychotics, anxiolytics, hypnotics, opioid analgesics, diuretics, and antihypertensives.[11] It has also been shown that benzodiazepine use may increase both the risk and severity of traumatic injury.[17] Pre-injury psychiatric medication use, in the presence of positive drug or alcohol testing, is associated with prolonged hospital lengths of stay and increased respiratory complications.[19] The use of both barbiturates and traditional antipsychotic agents may cause significant sedation and has been linked to impaired fine motor skills and driving performance.[20,21] On the other hand, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors may have potentially beneficial effects on cognitive recovery following traumatic brain injury.[22,23]

Cardiovascular non-diuretic drugs are tied as the second most prevalent medication group in this study. In fact, if cardiac non-diuretic and diuretic medication use in this study are combined, their prevalence exceeds the prevalence of neuro-psychiatric medications [Figure 2]. Cardiovascular agents were previously found to contribute to trauma morbidity risk.[15] Commonly observed side effects of antihypertensive medications include dizziness, fatigue, and weakness, all of which may impair driver performance and increase fall risk.[11] Increased risk of motor vehicle crashes has been associated with loop diuretics and potassium-sparing diuretics, alone or in combination.[11] In addition, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, sympatholytic agents, vasodilators, digitalis glycosides, and antiarrhythmics have all been associated with 23-79% increase in vehicular crash risk.[11] For patients with pre-existing cardiac disease, reintroduction of regular cardiac medications early during the recovery period may be important in limiting subsequent morbidity and mortality.[15]

Anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs, tied for the second most prevalent medication class overall, may have serious implications in trauma patients, but the impact is controversial. Previous studies have shown that anticoagulation with warfarin has deleterious consequences in the setting of head injury and may carry increased trauma mortality.[24] Clopidogrel and aspirin may also contribute to mortality associated with head trauma in the elderly, despite lower nominal injury severity.[25] It is important to note that platelet administration may not improve mortality in head injured patients receiving antiplatelet agents.[26]

We speculate that the results of the current study may reflect the overall progress in post-injury therapy of injured older adults. This is suggested by the findings that although polypharmacy was associated with more complications, longer hospital and ICU stays, no significant increases in patient mortality were noted. If one assumes that increasing polypharmacy represents greater medical complexity of the respective patient, our contention becomes more valid. While it is known that comparatively lower injury severity in the older trauma patient may be associated with worse outcomes,[27] few measures are available to reliably quantify such relationship in the context of pre-existing chronic health conditions. The CPS is an attempt to provide an easy-to-use assessment, in the context of traumatic injury, of the combined impact of the patient's comorbidities and the “intensity” of medical therapy utilized to treat the respective comorbid conditions. While it did not correlate with patient mortality, CPS was independently predictive of post-hospital discharge to a facility. This finding may be important in early identification of patients who need post-discharge placement and can potentially help reduce hospital stays, especially considering the fact that increasing polypharmacy (and thus, CPS) may predispose patients with lower acuity injuries to have more severe clinical course, longer hospital stays, and prolonged recovery [Table 2].

Strengths of this study include the availability of reliable detailed medication recording data, relatively large sample size, reporting on an increasingly important but largely neglected topic in the trauma community, and the introduction of the novel CPS. Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, lack of prospective validation of the CPS, and inability to determine causal relationships (inherent to retrospective data analysis). Although the CPS score has not been validated in the trauma population, we find it intriguing that CPS was associated with outcome variables more strongly than either polypharmacy or the number of comorbid conditions alone. Based on this study's findings, validation of the CPS score is currently being performed at our institution. The authors recognize that study outcomes may have been influenced by complications related to in-hospital polypharmacy and adverse medication interactions. However, due to the sensitive nature and limited access to adverse event reporting, we did not examine in this study the institutional data on adverse event reporting related to polypharmacy among study patients.

CONCLUSION

Over 40% of trauma patients, 45 years and older, were using 5 or more medications at the time of their injury. Although these patients do not appear to have worsened mortality, they were at increased risk of complications, had lower functional outcomes at discharge, and were noted to have longer hospital and ICU stays. CPS may be a useful adjunct to help quantify the severity of comorbid conditions in the context of medications used to treat these conditions and warrants further investigation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stawicki SP, Gerlach AT. Polypharmacy and medication errors: Stop, Listen, Look, and Analyze. OPUS 12. Scientist. 2009;3:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epping-Jordan JE, Pruitt SD, Bengoa R, Wagner EH. Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. QualSaf Health Care. 2004;13:299–305. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziere G, Dieleman JP, Hofman A, Pols HA, van der Cammen TJ, Stricker BH. Polypharmacy and falls in the middle age and elderly population. Br J ClinPharmacol. 2006;61:218–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montamat SC, Cusack B. Overcoming problems with polypharmacy and drug misuse in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 1992;8:143–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christy JM, Stawicki SP, Jarvis AM, Evans DC, Gerlach AT, Lindsey DE, et al. The impact of antiplatelet therapy on pelvic fracture outcomes. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4:64–69. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.76841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbett SM, Rebuck JA. Medication-related complications in the trauma patient. J Intensive Care Med. 2008;23:91–108. doi: 10.1177/0885066607312966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazarus HM, Fox J, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Pombo DJ, Burke JP, et al. Adverse drug events in trama patients. J Trauma. 2003;54:337–43. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000051937.18848.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baranzini F, Diurni M, Ceccon F, Poloni N, Cazzamalli S, Costantini C, et al. Fall-related injuries in a nursing home setting: Is polypharmacy a risk factor? BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:228. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hohl CM, Dankoff J, Colacone A, Afilalo M. Polypharmacy, adverse drug-related events, and potential adverse drug interactions in elderly patients presenting to an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:666–71. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.119456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeRoy A, Morse MM. In: U.S.DOT/NHTSA. Washington, DC: DTNH22-02-C-05075; 2008. Exploratory study of the relationship between multiple medications and vehicle crashes: Analysis of databases. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suelves JM, Martinez V, Medina A. Injuries from falls and associated factors among elderly people in Cataluna, Spain. Rev PanamSaludPublica. 2010;27:37–42. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892010000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohio trauma registry public records request packet. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec 19]. Available online at: http://www.publicsafety.ohio.gov/links//ems_otr_public_req_record.pdf .

- 14.Fastbom J. Increased consumption of drugs among the elderly results in greater risk of problems. Lakartidningen. 2001;98:1674–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy JM, van Rij AM, Spears GF, Pettigrew RA, Tucker IG. Polypharmacy in a general surgical unit and consequences of drug withdrawal. Br J ClinPharmacol. 2000;49:353–62. doi: 10.1046/1365-2125.2000.00145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spina E, Scordo MG. Clinically significant drug interactions with antidepressants in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:299–320. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wardle TD. Co-morbid factors in trauma patients. Br Med Bull. 1999;55:744–56. doi: 10.1258/0007142991902754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macdonald JB. The role of drugs in falls in the elderly. ClinGeriatr Med. 1985;1:621–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muakkassa FF, Marley RA, Dolinak J, Salvator AE, Workman MC. The relationship between psychiatric medication and course of hospital stay among intoxicated trauma patients. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15:19–25. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3280b17ea0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mintzer MZ, Guarino J, Kirk T, Roache JD, Griffiths RR. Ethanol and pentobarbital: Comparison of behavioral and subjective effects in sedative drug abusers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;5:203–215. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spina E, Scordo MG, D’Arrigo C. Metabolic drug interactions with new psychotropic agents. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2003;17:517–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourgeois JA, Bahadur N, Minjares S. Donepezil for cognitive deficits following traumatic brain injury: A case report. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;14:463–4. doi: 10.1176/jnp.14.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khateb A, Ammann J, Annoni JM, Diserens K. Cognition-enhancing effects of donepezil in traumatic brain injury. Eur Neurol. 2005;54:39–45. doi: 10.1159/000087718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pieracci FM, Eachempati SR, Shou J, Hydo LJ, Barie PS. Degree of anticoagulation, but not warfarin use itself, predicts adverse outcomes after traumatic brain injury in elderly trauma patients. J Trauma. 2007;63:525–30. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31812e5216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivascu FA, Howells GA, Junn FS, Bair HA, Bendick PJ, Janczyk RJ. Predictors of mortality in trauma patients with intracranial hemorrhage on preinjury aspirin or clopidogrel. J Trauma. 2008;65:785–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181848caa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downey DM, Monson B, Butler KL, Fortuna GR, Jr, Saxe JM, Dolan JP, et al. Does platelet administration affect mortality in elderly head-injured patients taking antiplatelet medications? Am Surg. 2009;75:1100–3. doi: 10.1177/000313480907501115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stawicki SP, Grossman MD, Hoey BA, Miller DL, Reed JF., 3rd Rib fractures in the elderly: A marker of injury severity. J Am Geriatri Soc. 2004;52:805–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]