Abstract

Simulation experiences have begun to replace traditional education models of teaching the skill of bad news delivery in medical education. The tiered apprenticeship model of medical education emphasizes experiential learning. Studies have described a lack of support in bad news delivery and inadequacy of training in this important clinical skill as well as poor familial comprehension and dissatisfaction on the part of physicians in training regarding the resident delivery of bad news. Many residency training programs lacked a formalized training curriculum in the delivery of bad news. Simulation teaching experiences may address these noted clinical deficits in the delivery of bad news to patients and their families. Unique experiences can be role-played with this educational technique to simulate perceived learner deficits. A variety of scenarios can be constructed within the framework of the simulation training method to address specific cultural and religious responses to bad news in the medical setting. Even potentially explosive and violent scenarios can be role-played in order to prepare physicians for these rare and difficult situations. While simulation experiences cannot supplant the model of positive, real-life clinical teaching in the delivery of bad news, simulation of clinical scenarios with scripting, self-reflection, and peer-to-peer feedback can be powerful educational tools. Simulation training can help to develop the skills needed to effectively and empathetically deliver bad news to patients and families in medical practice.

Keywords: Bad news delivery, end-of-life care, medical education, palliative care, simulation

INTRODUCTION

In the dynamic field of medical education, a debate continues regarding the benefits of traditional teaching methods versus simulation experiences in enabling learners to effectively and empathetically deliver bad news common to medical practice. Many physicians recall the adage, “See one—Do one—Teach one” which characterizes the traditional model of medical education. In this apprenticeship approach, role modeling and imitation are emphasized, learning is clinically oriented, feedback is limited, and active supervision is minimal. A major disadvantage is that many learners are later thrust into situations and experiences for which they were underprepared.[1] In response to this deficit, many medical schools and residencies are now incorporating novel educational approaches including simulation and role-playing. These newer educational modalities are currently being explored to address the inadequacies of traditional educational models. These techniques may be beneficial in regarding teaching medical students, physicians, and other healthcare providers the challenging skill of delivering bad news.

The acute phases of grief may manifest in an explosive manner and healthcare providers should be aware of the safety of all individuals in the medical setting. Violence in the workplace is common and some clinicians have reported feeling unsafe while working.[2] The delivery of bad news is an emotionally charged moment. Clinicians should take inventory of personnel present and their physical position, available supportive personnel, potential for violent escalation, and possible exit strategies. Supportive personnel such as security, pastoral care, nurses, and patient representatives may be helpful in the delivery and management of the patient and families ongoing needs. One must always be prepared for the worst-case scenario regarding both patients and their loved ones’ reaction to bad news. Preparing for worst case scenarios is important and taking preventive measures to ensure everyone's safety in the clinical setting is imperative.

TRADITIONAL EDUCATIONAL APPROACH

Historically, medical education utilized a tiered apprenticeship approach as an educational model. Students and residents have been encouraged to learn on the job, accepting responsibility for patients with minimal supervision. The primary advantage to this approach is that it allows trainees to model preceptors in a real-life clinical setting. However, Orgel et al. demonstrated a paucity of support for physician learners during their early and formative experiences with bad news delivery. Further, they identified the inadequacy of training in physicians at all levels in delivering bad news to patients and families.[3] In this setting, a request for help is often perceived as an admission of weakness, and learners are expected to function with minimal supervision and feedback by attending physicians. Health care providers are often expected to deliver bad news without a dedicated curriculum regarding how to perform this difficult and complicated portion of medical practice. Deep et al. studied residents, who had not had a formalized training curriculum addressing bad news delivery, and their communication with families regarding end-of-life care. They found dissatisfaction on the part of the residents and poor familial comprehension of end-of-life decisions.[4]

Self-reflection and preceptor evaluation of clinical performance in the delivery of bad news is important. Specific conversations both before and after family meetings and supplemental lectures have been shown to improve trainee's confidence in their skills delivering bad news, as demonstrated by Minor et al while examining a structured preceptorship in an intensive care rotation.[5] Unfortunately, learners may not have enough clinical opportunities delivering bad news, and they may require additional observational opportunities before achieving competence in this skill.

SIMULATION EDUCATION APPROACH

There is a growing trend among educators to use simulation to address the clinical deficits unique to delivering bad news. Examples of these communication deficits include unique barriers including variables such as age, gender, cultural background, and religious preferences of both patients and providers. Thornton et al. noted physicians communicated less supportive statements and spent less time during the delivery of bad news to families that were non-English speaking.[6] Barclay et al. commented on cultural issues leading to misperception inherent in the delivery of bad news to patient and families.[7] These cultural issues may be areas of weaknesses that can be addressed during simulation experiences and improved upon. Simulation offers a scripted educational experience for the learner with opportunities to assess skills longitudinally, to be objectively monitored, and to receive active feedback in a controlled and less intimidating setting. Potentially uncomfortable and even dangerous or violent responses can be mimicked and prepared for in a professional way through the use of simulation experiences. A learner can tailor these experiences to their own needs and can identify weaknesses without the pressure of real clinical practice.

Several studies have examined how simulation changes resident confidence in their own skills when delivering bad news in the clinical setting. Bowyer et al evaluated the combination of didactic lecture and simulation of a critically ill patient scenario followed by a family discussion. Residents were then asked to evaluate their own performance. In the study group, learners with variable experiences and diverse comfort levels were provided with a sheltered environment, scripted experiences, and educational tools to clearly, calmly, and effectively inform patients and families of bad news often delivered by a physician. Students who had undergone formal training prior to the exercise showed significant improvement in self-assessment compared to control groups.[8] In another study, Hales et al looked at the use of standardized families with an end of life care coaching team in improving interactions in a range of end-of-life situations conducted during a one-day workshop. Each participant was evaluated by self-completed pre- and post-workshop evaluations. The participants were given several scenarios, and they were given coaching before and during the workshops with immediate feedback. They showed statistically significant improvement in their own perception of competency in dealing with end-of-life discussions after the workshop.[9]

There is strong evidence to show that simulation may better address the learner's needs in delivering bad news. Reviews of simulation education have demonstrated that the skills of residents improved by standards of external examiners. Smuilowicz et al. used a randomized control trial to evaluate both residents’ perceived confidence in this process, as well as external evaluators grading of the resident's skill at bad news delivery. The residents were sent on a short retreat where they had standardized patients, and their subsequent evaluation was based on their ability to deal with giving news and handling different emotional responses. There was statistical improvement in both resident self-perceived confidence and the blinded evaluator's assessment in their abilities.[10] Bylund, et al. examined various programs aimed at developing communications skills for practitioners delivering bad news in a clinical setting and found positive effects of workshop skills training demonstrated by objective reviewers grading physician–patient interaction.[11]

Simulation alone cannot ultimately substitute for the powerful example of active teaching by attending physicians. Learners should be involved in the process of delivering bad news during clinical scenarios and physically present even if they are not the primary caregivers. Simulation remains an important, innovative, and effective learning tool in the medical educational of both the post-graduate and medical student settings. Ultimately, a multi-faceted approach to training in the delivery of bad news provides the best approach.

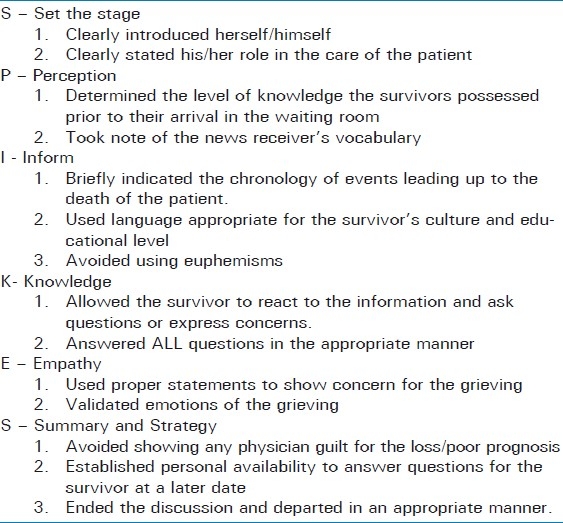

Several models exist regarding the aforementioned approach to bad news delivery education. In their review article, Rosenbaum et al. discussed the importance of longitudinal experiences for learners throughout their medical education as an important part of developing competent, effective, and caring physicians able to deliver bad news gracefully to patients and their families.[12] Park et al has specifically suggested a SPIKES protocol in Table 1. “SPIKES” serves as a useful acronym for recall of a scripted methodology in bad news delivery.

Table 1.

SPIKES Protocol Directions: Please indicate whether the physician completed the stated actions, with Y=completed (Yes) or N = did not complete (No)

In this study, didactic lectures in combination with role-play between attending physicians and resident physicians showed an increase in perceived confidence by residents and statistically significant improvement in the delivery of bad news by external evaluators.[13]

Education through the use of simulation encounters are already employed elsewhere in medical training. Medical students now take the United States Medical Licensure Exam Step 2 Clinical Knowledge, and medical education curriculums have incorporated appropriate simulated patient training such as the observed structured clinical exam (OSCE). In this format a staged patient encounter with a trained patient is either videotaped or observed by a third party followed by a debriefing. This has been used to teach many scenarios in medical student education such as the difficult patient, routine history and physicals, pediatric encounters, and delivering bad news. This method has shown OSCE training as an effective method to teach end-of-life discussions and measure improvement in a learner's skills.[14]

SUMMARY

Simulation-based education cannot replace real-life experiences and the need for positive demonstrative teaching by attending physicians. However, the simulation educational model used in teaching the delivery of bad news provides many advantages that can be optimized to effectively educate learners of varying backgrounds in the caring and competent delivery of bad news to patients and families in medical practice. The experience provided by repeat simulation scenarios may improve the learner's ability to express empathy, communication skills, and anxiety. Simulation experiences can be supplemented with real-time encounters where learners witness the delivery of bad news by an experienced clinician.

Simulation training has been shown to be a powerful teaching tool in many areas including the delivery of bad news. While simulation cannot replace role modeling and direct patient encounters, it may be able to help fill a deficit in this area of education. The authors feel that utilizing scripted simulated patient encounters will augment real-life encounters to provide healthcare personnel with improved tools in the delivery of bad news. In addition this training format may improve patient and family comprehension of information communicated by practitioners. Implementation of this training, including the exact number of experiences recommended and the timing in which simulation encounters should be placed in the training process, has yet to be established. Future studies are suggested to address these questions.

Delivering bad news is a challenge common to medical practice. The gravity of many of these conversation demands the necessary skills to adequately assess a patient's and family's emotions, follow an understandable script, and maintain awareness of the stages of grief with both the subtle and more tangible expressions of the grieving process. This point was emphasized in a Time article about the recent shootings in Tucson, Arizona entitled, “Good News About Grief.” Grieving is inherently individual, but a repeatable script used by medical personnel delivering bad news can be the foundation from which to engage those persons no matter their emotional reaction. Empathy combined with purposeful communication of the key facts pertinent to the unfortunate situation will aid medical personnel in the effective communication of the information important for patients and families to begin their grieving process. Offering assistance or practicing the discipline of revisiting patients and families who you have shared bad news with allows access for persons to ask any questions left unanswered in an initial encounter. Time declares, “the latest research indicates that grief is not a series of steps but rather a grab bag of symptoms that come and go and, eventually, simply lift.”[15]

Delivering bad news is never easy and is challenging to both those who deliver and those who receive this information. Whatever the unfortunate situation, delivering bad news is a common experience in emergency medicine, critical care and trauma units. In fact, becoming the bearer of such news can produce introspection in clinicians and can evoke strong personal emotions. These challenges should not be underestimated, but should encourage educators to explore the most effective educational approaches available. Preparing providers to effectively deliver bad news may be a process of graded skills first learned in a skills lab and then demonstrated in the clinical setting. Focusing on this skill can help prepare for the situation management and the desired outcome of safety and empathy for the grieving.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orlander JD, Fincke BG, Hermanns D, Johnson GA. Medical residents’ first clearly remembered experiences of giving bad news. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:825–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowalenko T, Walters BL, Khare RK, Compton S. Michigan College of Emergency Physicians Workplace Violence Task Force. Workplace Violence: A Survey of Emergency Physicians in the State of Michigan. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:142–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orgel E, McCarter R, Jacobs S. A failing medical educational model: A self-assessment by physicians at all levels of training of ability and comfort to deliver bad news. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:677–83. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deep KS, Griffith CH, Wilson JF. Communication and decision making about life-sustaining treatment: Examining the experiences of resident physicians and seriously-ill hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1877–82. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0779-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minor S, Schroder C, Heyland D. Using the intensive care unit to teach end-of-life skills to rotating junior residents. Am J Surg. 2009;197:814–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thornton JD, Pham K, Engelberg RA, Jackson JC, Curtis JR. Families with limited English proficiency receive less information and support in interpreted intensive care unit family conferences. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:89–95. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181926430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barclay JS, Blackhall LJ, Tulsky JA. Communication strategies and cultural issues in the delivery of bad news. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:958–77. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.9929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowyer MW, Hanson JL, Pimentel EA, Flanagan AK, Rawn LM, Rizzo AG, et al. Teaching breaking bad news using mixed reality simulation. J Surg Res. 2010;159:462–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hales BM, Hawryluck L. An interactive educational workshop to improve end of life communication skills. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28:241–8. doi: 10.1002/chp.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szmuilowicz E, el-Jawahri A, Chiappetta L, Kamdar M, Block S. Improving residents’ end-of-life communication skills with a short retreat: A randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:439–52. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bylund CL, Brown RF, di Ciccone BL, Levin TT, Gueguen JA, Hill C, et al. Training faculty to facilitate communication skills training development and evaluation of a workshop. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:430–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Lobas JG. Teaching medical students and residents skills for delivering bad news: A review of strategies. Acad Med. 2004;79:107–17. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park I, Gupta A, Mandani K, Haubner L, Peckler B. Breaking bad news education for emergency medicine residents: A novel training module using simulation with the SPIKES protocol. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3:385–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.70760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams DM, Fisicaro T, Veloski JJ, Berg D. Development and evaluation of a program to straighten first year residents’ proficiency in leading end-of-life discussions. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010 Dec 13; doi: 10.1177/1049909110391646. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konigsberg RA. Good news about grief. Time. 2011 Jan 24;:42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]