Abstract

Pain relief and palliative care play an increasingly important role in the overall approach to critically ill and injured patients. Despite significant progress in clinical patient care, our understanding of death and the dying process remains limited. For various reasons, people tend to delay facing questions associated with end-of-life, and the fear of the unknown often creates an environment of avoidance and an atmosphere of taboo. The topic of end-of-life care is multifaceted. It incorporates medical, ethical, spiritual, and religious aspects, among many others. Our ability to sustain the lives of the critically ill may be complicated by continuing life support in medically futile scenarios. This article, as well as the remainder of the IJCIIS Symposium on End-of-Life in Trauma/Intensive Care Unit, will explore the most important issues in the field of modern end-of-life care and palliative medicine, with a focus on critically ill and injured patients.

Keywords: Pain and palliative care, Intensive care unit, Latest developments, Clinical standards

Important realities in the field of end-of-life care and palliative critical care (PCC) are emerging as our ability to care for critically ill patients improves. Achieving a balance between rescuing vulnerable survivors and providing comfort to patients and families when death is inevitable remains difficult. This task is often negotiated in the context of an increasingly complex medical environment and prognostic uncertainty. Even under optimal conditions, the intensive care experience is onerous for all patients and families, making end-of-life discussions more difficult.[1–5] Therefore, a paradigm shift is occurring toward integrating palliative care principles a priori for all admissions to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).[6] A commonly utilized intermediate or “trigger” approach to activating a palliative care (PC) consultation can potentially limit the effective availability of PCC to as few as 2–5% of patients, even when PC consultation triggers are developed by experienced palliative care clinicians.[7]

In its broadest sense, palliative care can be viewed as the critical care specialist's tool to diagnose and treat suffering.[8] While “distress” is the new code word for suffering,[9] unless the critical care team can agree on and recognize such “distress” in patients and families, it is inherently difficult to treat. Unaddressed suffering leads to poor patient and family satisfaction, may result in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-like symptoms among family members, and prolongs time in the ICU on technological life support without clearly defined benefits. The definition of “distress” is complex, as contributing factors may include physical symptoms, psychological responses to the illness, and decisions forced upon patient and family by the trajectory of illness.

EMERGING COMPETENCIES IN THE ICU

Humanizing the clinical experience for families in the ICU may improve family satisfaction and prompt more effective use of technological ICU resources. Schaefer and Block identified trends toward three broad groups of clinical competencies that positively impact length of ICU stay, family satisfaction, and family bereavement outcomes: Empathic communication, skillful discussion of prognosis, and effective shared decision-making.[10] These competencies are brought to bear in the setting of a proactive family conference. The presence and content of a family meeting documented in the medical record is in itself a quality measure of increasing focus. These three core components of quality care in the ICU deserve emphasis in clinical encounters and educational interventions.[10]

A fourth competency, active listening, deserves special attention because it has been identified as a major determinant of patient/family satisfaction.[11] Silence during strategic portions of family meetings may prove difficult for clinicians. In one study, among 51 audio-taped ICU family conferences, averaging 32 minutes with 214 family members, clinicians spoke >70% of the time while family members were given ~30% of the total conference time.[11] Of interest, the highest rates of satisfaction among families in care withdrawal discussions correlated with greater proportions of family speech time. There was no association between satisfaction scores and total duration of the conference, physician specialty, physician experience, or whether the physician was faculty or a trainee.[11] The investigators also found a negative correlation between the proportion of family speech and the degree of family-perceived conflict between family members and the physician leading the conference.[11] Therefore, the optimal ICU communication model should incorporate strategic clinician silence and the understanding that families need to be heard. Given that critical care training and practice emphasize core competencies,[12] it is reasonable to propose that PCC principles should be incorporated among those competencies.

PAIN AND NON-PAIN SYMPTOMS

Three notable studies have identified pain in ICU patients as the dominant symptom/stressor recalled by survivors after an ICU stay.[4,13,14] Presently, ICU patients are considered a special population at risk for undertreated pain.[15] The process of pain assessment, intervention, and reassessment should be performed on multiple occasions daily.[16] Pain assessment and therapy in communicative versus non-communicative patients present different and distinct sets of problems for the treating physician. It is important to remember that agitation may be a manifestation of a pain response,[17] and that pain assessment and therapy is challenging in non-communicative patients requiring sedation for mechanical ventilation. Only recently have validated pain assessment tools been developed for non-communicative ICU patients.[18,19] Attention to accurate and timely pain assessments and the use of opioids specifically to treat pain require a systematic approach.[17] Among patients requiring sedation for mechanical ventilation, opioids are frequently overused for sedation, though available evidence suggests that non-opioid alternatives may be more appropriate, especially when balancing periods of planned wakefulness to minimize cognitive dysfunction.[17]

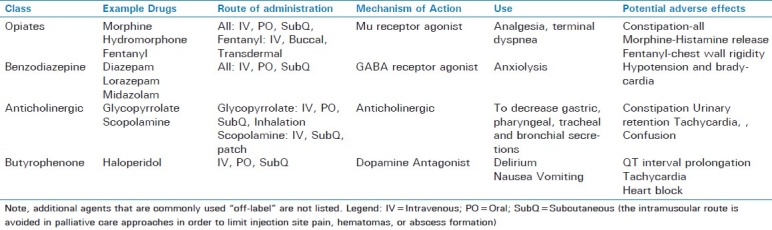

Common non-pain symptoms such as delirium, dyspnea, and anxiety are very distressing to both patients and families. Delirium may be caused or exacerbated by analgesics and other medications.[20] When patients are dying, terminal delirium may not be reversible. For patients withdrawn from technological support, the primary goal should be symptom relief. Therefore, a symptom is the indication for a medication, and the pharmacologic intervention and response are documented. “Titrate drip to effect” orders do not address the need for assessment and reassessment of symptoms, and a drip change may take hours to reach a new steady-state blood level to achieve its clinical effect. For continuous symptoms, scheduled and as-needed medications are indicated to maintain therapeutic blood levels of appropriate agents. While opioids are the drugs of choice for pain and dyspnea, other agents are indicated for delirium (e.g. haloperidol) and anxiety (e.g. benzodiazepines), and using opioids for all symptoms is not optimal. Assessment of dyspnea in patients unable to speak is challenging, but validated tools are available.[21] An overview of medication classes and agents commonly used for pain control and palliative care is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pharmaceutical agents commonly used for pain control and palliative care

FAMILY DISTRESS AND RISKS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL SEQUELAE

Over two-thirds of family members visiting their hospitalized relative in the ICU report anxiety and depression after the experience.[3] Azoulay et al demonstrated that more than one-third of family members had PTSD-like symptoms 90 days after a patient's ICU discharge or death.[22] Higher rates of posttraumatic stress symptoms were found among family members who felt that the information provided in the ICU was incomplete (48.4%), who shared in any decision- making (47.8%), whose relative died in the ICU (50%), whose relative died after end-of-life decisions (60%), and who shared in end-of-life decisions (81.8%).[22] Thus, early and proactive approaches are advocated. A prospective intervention to counsel family members whose loved ones died in an ICU was studied, comparing an informational brochure and a proactive family conference to “usual care”.[23] The intervention conferences were designed to discuss end-of-life issues and withdrawal of futile technological interventions. Clinicians also provided family members with additional opportunities to discuss the patient's wishes, to convey emotions, to ease feelings of guilt, and to understand the goals of care. Bereavement was substantially reduced in the study group (lower validated stress/PTSD scores/criteria, and prevalence of anxiety/depression) as compared to controls.[23]

MEDICAL FUTILITY – A SHIFT FROM INTENSIVE CARE TO INTENSIVE CARING

The American Thoracic Society stated in 1991 that a situation compatible with medical futility was present “if reasoning and experience indicate that the intervention would be highly unlikely to result in a meaningful survival for that patient”.[24] In 1997, the Society of Critical Care Medicine acknowledged that “treatments should be defined as futile only when they will not accomplish their intended goal.”[25] The statement is further qualified by offering that “treatments that are extremely unlikely to be beneficial, are extremely costly, or are of uncertain benefit may be considered inappropriate and hence inadvisable, but should not be labeled futile.”[25] Despite differences, consensus can be reached when clinicians of various specialties collaborate.[26]

In family conferences to discuss goals of care, physicians in the ICU must often rely on surrogates to determine “best interest” of critically ill patients. Are surrogates readily identified and relevant content of family conferences documented? In one study, investigators evaluated ICU medical records in Ontario, Canada.[27] In a cohort of 105 elderly patients with high APACHE II scores (and withdrawal of life support preceding death) over half of the intensivists had timely communications (median 17 hours from ICU admission). The surrogate decision maker was documented for only 10% of patients. Explicit survival estimates were noted in only half of patient charts. Physicians infrequently documented their own predictions and assessments of the patient's post-ICU functional status (20%). Poor documentation was also seen for anticipated need for chronic care, post ICU quality of life, and documentation of the patient's own perspectives on these issues (all documented in less than 5 percent of charts).[27]

An initial proactive family meeting shortly after the admission, with regular follow-up family meetings, take on an important role with increasing medical futility. While clinical teams may focus on “one-time transactions” such as the do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order or a therapeutic withdrawal, the family focus is a “continuous process”, and time is needed for informational, relational, spiritual, cultural processing, acceptance, and other adaptations to occur. Religious beliefs, ethnicity, and cultural background of the parties involved may affect the interventions received or withdrawn when caring for dying patients, and heightened physician awareness is warranted.[28]

Setting expectations early and repeatedly is also helpful. Since up to one-fourth of critically ill patients in the U.S. are likely to die within months of initial ICU admission, it makes intuitive sense to address the possibility of death early in the course of illness. Concern, compassion, and confidence can be affirmed in these situations. Clinicians should discuss possible adverse events during family meetings. Do policies and procedures in your ICU reflect contingencies for adverse outcomes or medically futile care? The literature supports the need for better approaches to this specific aspect of critical illness. In one study, only 21% of New Zealand ICUs (representing 83% of ICU admissions) had a written policy for withholding and withdrawing life support in the context of medically futile care.[29] In addition, it is important to note that <20% of nurses have formal training in withdrawal of life support, and <40% receive an adequate orientation that includes education on withdrawal of life support and family care.[29–31] Management of medical futility continues to have considerable geographic variation, especially in regard to routine PC or ethics consultations, family conferences, and standardized protocols for withdrawal of life support. All of these aspects require coordination and effective implementation.[30]

There is a considerable variation in practices and training among critical care nurses for end-of-life care.[31] Nurses play a key role in the withdrawal of life support (WDLS) as they are at the bedside more than any other member of the ICU team and implement the orders to withdraw life support. Of interest, one study showed that only 15.5% of 463 ICU nurse respondents had a required course or information in a required course that covered WDLS as part of their nursing curriculum, and >63% (292/463) reported that they had no training for WDLS during orientation.[31] These data suggest that ICU nurses may not always receive adequate professional training to care for patients at the end-of-life. Enhancing end-of-life training and support for ICU nurses is an important method of reducing professional burnout.[32] Nurses experience moral distress when involved in futile care and may need emotional/spiritual support.[33] The reader is invited to examine accompanying articles on medical futility and nursing care aspects of end-of-life care in this symposium.

PALLIATIVE CARE - ICU PROGRAM INTERVENTIONS AND QUALITY IMPROVEMENT INITIATIVES

The ICU is a complicated work environment and barriers to end-of-life care are well-recognized. In 2006, the Critical Care Peer Workgroup of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care Project surveyed 1205 ICU directors.[34] ICU directors identified the top three barriers to be: (a) Insufficient clinician training in communication about end-of-life care; (b) Inadequate communication between the ICU team and patient/families about goals of care; and (c) Fear of legal liability associated with foregoing life-sustaining treatments.[34] Patient/family barriers to optimal end-of-life care included “unrealistic patient and/or family expectations about prognosis or effectiveness of ICU treatment” and “inability of many patients to participate in treatment discussions.”[34] While more deaths occur in ICUs as compared to other locations in the hospital, the science of ICU risk prediction appears to be more valuable to clinicians and researchers than to individual patients and families.[35]

How should ICU leaders implement new principles of simultaneous palliative and curative care in the ICU? The oncology world has recognized this paradigm shift, noting that PC should begin at initial diagnosis of cancer. Some investigators have implemented similar principles with each ICU admission using an integrative approach.[5,6] Early routine interventions are important especially because of the inaccuracies of physician prognostication of illness outcomes.[36]

Should palliative care be performed incrementally or systemically in the ICU? In “trigger”-based approaches, the patients in a medical ICU[37] appear to derive more benefit than surgical ICU patients undergoing palliative care consultation by use of clinical parameters.[7] Outside of the ICU, in a randomized trial conducted at Kaiser Permanente, hospitalized patients treated by consultative palliative care services were more satisfied than those treated with the “usual care” approach.[38] Integration of palliative care services so that they become “embedded” in daily care with specialty services results in sustained patient satisfaction.[39] Integration of palliative care for ICU patients is advocated by multiple professional critical care societies.[40–43] In October, 2012, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) will modify hospital payment structures to include withholding payments for selected adverse outcomes, clinical quality, and patient experience scores. Given that the critical care setting is a high stakes environment for hospital mortality, satisfaction, and costs, intensivists may prefer to consider taking a lead role in developing performance improvement projects on an integrative scale. Systemic barriers to implementation can be successfully confronted with an organized approach.[44] Examples of successful integrative approaches are worth a closer look.

The Voluntary Hospitals of America, Incorporated (VHA) is a conglomerate of 1400 non-profit hospitals and other healthcare organizations. Formed in 1977 to reduce hospital purchasing and other costs, the organization also focuses on ways to enhance clinical performance in various areas, including critical care. In 2004, VHA member hospitals were urged to optimize critical care delivery for peak performance by 2015. The VHA already has helped manage phase one of the “Transformation in the ICU” project among member hospitals beginning in 2001. This collaboration of 23 member hospitals resulted in a substantial reduction in ventilator-associated pneumonias (by 41%, with an 18% reduction in mortality).[45]

The integrative approach advocated by the VHA is termed “rapid-cycle quality improvement program”, and their methods were trialed at Johns Hopkins, but are largely proprietary to member institutions.[45] A follow-up project, initiated at the request of participating ICUs, included pilot testing of a “palliative care bundle” which began implementation in 2005, and included pain measures and eight additional performance measures.[45] This VHA PCC “bundle” of practices and measures was primarily developed from Critical Care Peer Workgroup of Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, and Joint Commission standards. The palliative care bundle approach is an integrative approach much like a clinical pathway.[46] On the first day of an ICU admission, the participating ICU team identifies a principal family decision maker, addresses advance directive status and CPR status, and distributes informational material to the patient and family. Additionally, pain is assessed and treated regularly. On day three, social work assistance and counseling is offered and initiated, as well as spiritual support offered from hospital pastoral care specialists. On day 5, a proactive family meeting is conducted for all admissions. The influence of this integrative approach is measured from satisfaction surveys, administrative data, and retrospective chart reviews.[45]

A second integrative approach, the NIH-funded implementation program “IPAL-ICU” (Improving Palliative Care in the ICU) is endorsed by the Center to Advance Palliative Care. IPAL is a toolkit for implementing PC guidelines based upon process improvement principles advocated by Pronovost's successful model of a sustained decrease in line infections (to zero) in a hospital setting.[47] Active collaboration with a palliative care team to implement integrative care initiatives systemically in the ICU is an effective approach and has been endorsed by critical care consensus panels.[40–43] Half of families in the ICU experience inadequate communication with physicians.[48] The majority of patients cannot participate in complex decisions, their surrogate decision-makers are not ready to make decisions, and surrogates prefer shared decision-making with physicians.[49] Process innovations such as IPAL will help clinical teams implement guidelines and enhance communications in a more effective manner.

SPIRITUAL AND CULTURAL ASPECTS OF END-OF-LIFE CARE

Multi-culturalism and religious (or atheist) tolerance constitute defining features of modern progressive societies. Those who care for the critically ill must maintain a high degree of sensitivity toward a dying patient's cultural and spiritual background. In addition to addressing physical suffering, physicians can extend their caring by acknowledging and easing psychosocial, existential, and spiritual suffering.[50] The American College of Critical Care Medicine advocates assessment of spiritual needs as part of the role of critical care clinicians, who should possess fundamental skills in spiritual assessment and referral.[51]

Patients and families are challenged by critical illness to find meaning and transcend suffering in the ICU setting. Their religious background, or non-religious spiritual-existential beliefs, are important coping tools for adaptation and redefining hope. Although no single human being is alike with regards to their closely held personal beliefs and individual value systems, certain generalizations can be considered. More details on religious and cultural aspects of end-of-life palliative care are included in other articles within this Symposium; a brief overview is provided here.

In Islam, death can only occur by God's permission, and the sanctity of life is unquestioned according to the Quran.[52] Pain is thought to function as a divine tool in demonstrating God's purpose and is meant to remind people that everyone belongs to God.[52] However, there are Muslim scholars who believe pain at the end-of-life (terminal illness) may receive analgesic medicine.[53] To this end, Saudi Arabia has enacted a policy that addresses all aspects of end-of-life care regarding Muslim patients.[54]

In Judaism, everyone's body belongs to God.[55] Suicide and assisted suicide are prohibited (as they are in Islamic culture). In end-of-life situations, Jews are permitted to pray to God to allow death to come to them or a loved one.[55] However, a cure should always be sought, death must not be hastened yet the dying process should not be prolonged, and the patient's benefit is always the goal.[55] This broad view could lead to considerable disagreements, depending on the particular circumstances and the specific Jewish religious group involved.

Hindu ethics advocate that “a good death” occurs “in old age, and at the right time, and in the right place”.[56] Although there are historical aspects of religious suicide and voluntary death, there is a firm distinction between those who are spiritually advanced and wish to end their life and those who wish to their life because of pain. The latter is considered a selfish death and is morally wrong; suffering is seen as cleansing and purifying.[56] In India, critical care physicians withdraw care at the end-of-life less frequently than their Western counterparts, likely a multifactorial phenomenon related partly to legal concerns and public policy.[57]

An approach to end-of-life and palliative care has been poorly studied among atheist patients.[58] Atheists do not believe in God or an afterlife and thus represent a unique group that contrasts with other belief systems.[58] Spirituality conveys a sense of personal, existential meaning for life, and as such can be evaluated in a spiritual assessment for atheist patients. Atheists’ preferences for end-of-life care are fairly consistent within that group, and reflect many of the components of a “good death” previously described in the literature. These elements include: (a) Pain and symptom management; (b) Clear decision-making; (c) Preparation for death; (d) Completion; and (e) Affirmation of the whole person.[59] Respect for professional and personal boundaries is an important expectation for both patients and caregivers. Investigators recommend that healthcare workers respect a philosophy of non-belief to meet a dying atheist's declared preferences.[58]

For the Christian patient and family in the ICU, the end of life is a time for reconciliation with God and family, and a growing dependence upon Jesus for the passage through death to eternal life. Patients and families from liturgical faith communities may rely upon rituals such as “anointing of the sick” before death. (e.g., Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, some Protestant denominations).[60] Lack of understanding of the role of healing and miracles in the Christian faith on the part of clinical teams has the potential to adversely affect interactions between the healthcare team and the patient/family.[61]

In view of such spiritual and cultural diversity in the modern world, education in the various patient beliefs at end-of-life should be pursued by those providing both critical and palliative care, and should be an important priority in residency training and in medical school education. Many studies also advocate patient and family support from a trained chaplain or spiritual care advisor in the ICU. Family satisfaction in the ICU is higher if a chaplain or spiritual advisor is involved in care at least 24 hours prior to a patient's death.[62] The reader is referred to other articles in this series for additional information regarding religion and spirituality in the end-of-life setting.

CONCLUSIONS

While the ICU is a familiar place for those who work there, it is an intimidating, foreign, and uncomfortable environment for patients and families. Palliative care has become an increasingly helpful and effective component of the overall critical care approach to relieve ICU-related distress for patients and families, including at the end-of-life. Medical and surgical critical care societies have outpaced other specialty societies in adopting consensus guidelines for palliative care to support patients and families in the ICU. Clinical competencies are emerging to enhance critical care training, education, and practice in palliative critical care.

Future CMS payment reforms focusing on quality, resource, and satisfaction outcomes in U.S. hospitals may stimulate hospital ICU services to further integrate palliative care components. Current literature suggests that efforts to enhance communications and care for ICU patients and families may more effectively be implemented into daily practice by using integrative ICU systems design, as compared to ad hoc PC consults or PC consult triggers.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nelson J. Identifying and overcoming the barriers to high-quality palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S324. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237249.39179.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, et al. Risk of posttraumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, Bollaert PE, Cheval C, Coloigner M, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2005;20:90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson JE, Meier DE, Oei EJ, Nierman DM, Senzel RS, Manfredi PL, et al. Self-reported symptom experience of critically ill cancer patients receiving intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:277–82. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA. Interdisciplinary model for palliative care in the trauma and surgical intensive care unit: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Demonstration Project for Improving Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S399–403. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237044.79166.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosenthal A, Murphy P, Barker L, Lavery R, Retano A, Livingston D. Changing the culture around end-of-life care in the trauma intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2008;64:1587. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318174f112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley C, Weaver J, Brasel K. Addressing access to palliative care services in the surgical intensive care unit. Surgery. 2010;147:871–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:639–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198203183061104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holland JC, Bultz BD. The NCCN guideline for distress management: A case for making distress the sixth vital sign. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaefer KG, Block SD. Physician communication with families in the ICU: Evidence-based strategies for improvement. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15:569–77. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328332f524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Shannon SE, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1484–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grenvik A, Pinsky MR. Evolution of the intensive care unit as a clinical center and critical care medicine as a discipline. Crit Care Clin. 2009;25:239–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puntillo K. Pain experiences of intensive care unit patients. Heart Lung. 1990;19:526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novaes M, Knobel E, Bork A, Pavao O, Nogueira-Martins L, Bosi Ferraz M. Stressors in ICU: Perception of the patient, relatives and health care team. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1421–6. doi: 10.1007/s001340051091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT) JAMA. 1995;274:1591–8. [Published erratum appears in JAMA 1996;275:1232] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puntillo K, Pasero C, Li D, Mularski RA, Grap MJ, Erstad BL, et al. Evaluation of Pain in ICU Patients. Chest. 2009;135:1069–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honiden S, Siegel MD. Analytic Reviews: Managing the Agitated Patient in the ICU: Sedation, Analgesia, and Neuromuscular Blockade. J Intensive Care Med. 2010;25:187–204. doi: 10.1177/0885066610366923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gélinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, Viens C, Fortier M. Validation of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool in Adult Patients. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:420–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topolovec-Vranic J, Canzian S, Innis J, Pollmann-Mudryj MA, McFarlan AW, Baker AJ. Patient Satisfaction and Documentation of Pain Assessments and Management After Implementing the Adult Nonverbal Pain Scale. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19:345–54. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouimet S, Kavanagh BP, Gottfried SB, Skrobik Y. Incidence, risk factors and consequences of ICU delirium. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:66–73. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell ML, Templin T, Walch J. A Respiratory Distress Observation Scale for Patients Unable To Self-Report Dyspnea. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:285–90. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Th oracic Society. Withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:478–85. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-6-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Society of Critical Care Medicine. Consensus statement of the Society of Critical Care Medicine's Ethics Committee regarding futile and other possibly inadvisable treatments. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:887–91. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199705000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sibbald R, Downar J, Hawryluck L. Perceptions of “futile care” among caregivers in intensive care units. CMAJ. 2007;177:1201–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratnapalan M, Cooper AB, Scales DC, Pinto R. Documentation of best interest by intensivists: A retrospective study in an Ontario critical care unit. BMC Med Ethics. 2010;11:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curlin F, Nwodim C, Vance J, Chin M, Lantos J. To Die, to Sleep: US Physicians′ Religious and Other Objections to Physician-Assisted Suicide, Terminal Sedation, and Withdrawal of Life Support. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25:112. doi: 10.1177/1049909107310141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho KM, Liang J. Withholding and withdrawal of therapy in New Zealand intensive care units (ICUs): A survey of clinical directors. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004;32:781–6. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0403200609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curtis J. Interventions to improve care during withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:S116–31. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirchhoff KT, Kowalkowski JA. Current Practices for Withdrawal of Life Support in Intensive Care Units. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19:532–41. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Embriaco N, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Pochard F, Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:482–8. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282efd28a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrell BR. Understanding the moral distress of nurses witnessing medically futile care. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:922–30. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.922-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson JE, Angus DC, Weissfeld LA, Puntillo KA, Danis M, Deal D, et al. End-of-life care for the critically ill: A national intensive care unit survey. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2547–53. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239233.63425.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gartman EJ, Casserly BP, Martin D, Ward NS. Using serial severity scores to predict death in ICU patients: A validation study and review of the literature. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15:578–82. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328332f50c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scitovsky AA. “The high cost of dying”: What do the data show. 1984? Milbank Q. 2005;83:825–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norton S, Hogan L, Holloway R, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley M, Quill T. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: Effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1530–5. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, McGrady K, Beane J, Richardson RH, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:180–90. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adolph MD, Taylor RM, Ross PM, Vaida AM, Moffatt-Bruce SD. Evaluating cancer patient satisfaction before and after daily multidisciplinary care for thoracic surgery inpatients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:9605. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:605–22. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Truog RD, Cist AF, Brackett SE, Burns JP, Curley MA, Danis M, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: The Ethics Committee of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2332–48. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, Fahy BF, Hansen-Flaschen J, Heffner JE, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: Palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:912–27. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, Cassell J, Cox P, Hill N, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU: Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:770–84. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson JE. Identifying and overcoming the barriers to high-quality palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S324–31. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237249.39179.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Voluntary Hospital Association V. Transforming Critical Care: Survival Planning for 2015. VHA's 2004 Research Series. Available from: https://www.vhafoundation.org/documents/planning2015.pdf .

- 46.AHRQ / Rand SCE-bPC. Cancer Care Quality Measures: Symptoms and End of Life Care. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Number 137. 2006. [Last accessed on 2010 Oct 31]. Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/eolcanqm/eolcanqm.pdf .

- 47.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ. 2008;337:a1714. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3044–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Peters S, et al. Decision-making in the ICU: Perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lo B, Quill T, Tulsky J. Discussing palliative care with patients. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:744–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: A consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:953. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zahedi F, Larijani B, Bazzaz JT. End of life ethical issues and Islamic views. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;6:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khomeini R. Rulings on the final moments of life. In: Rohani M, Noghani F, editors. Ahkam-e Pezeshki. Vol. 306. Tehran, Iran: Teymurzadeh Cultural Publication Foundation; 1998. Rulings No. 1-3. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gouda A, Al-Jabbary A, Fong L. Compliance with DNR policy in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:2149–53. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1985-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dorff EN. End-of-life: Jewish perspectives. Lancet. 2005;366:862–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Firth S. End-of-life: A Hindu view. Lancet. 2005;366:682–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barnett VT, Aurora VK. Physician beliefs and practice regarding end-of-life care in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;12:109–15. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.43679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith-Stoner M. End-of-Life Preferences for Atheists. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:923–8. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. In search of a good death: Observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:825–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woll M, Hinshaw D, Pawlik T. Spirituality and Religion in the Care of Surgical Oncology Patients with Life-Threatening or Advanced Illnesses. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3048–57. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Delisser HM. A practical approach to the family that expects a miracle. Chest. 2009;135:1643–47. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wall R, Curtis J, Cooke C, Engelberg R. Family Satisfaction in the ICU. Chest. 2007;132:1425. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]