Abstract

Anethum graveolens L. (dill) has been used in ayurvedic medicines since ancient times and it is a popular herb widely used as a spice and also yields essential oil. It is an aromatic and annual herb of apiaceae family. The Ayurvedic uses of dill seeds are carminative, stomachic and diuretic. There are various volatile components of dill seeds and herb; carvone being the predominant odorant of dill seed and α-phellandrene, limonene, dill ether, myristicin are the most important odorants of dill herb. Other compounds isolated from seeds are coumarins, flavonoids, phenolic acids and steroids. The main purpose of this review is to understand the significance of Anethum graveolens in ayurvedic medicines and non-medicinal purposes and emphasis can also be given to the enhancement of secondary metabolites of this medicinal plant.

Keywords: Anethum graveolens, ayurvedic uses, carvone, limonene, monoterpenes, review

INTRODUCTION

The genus name Anethum is derived from Greek word aneeson or aneeton, which means strong smelling. Its common use in Ayurvedic medicine is in abdominal discomfort, colic and for promoting digestion. Ayurvedic properties of shatapushpa are katu tikta rasa, usna virya, katu vipaka, laghu, tiksna and snigdha gunas. It cures ‘vata’, ‘kapha’, ulcers, abdominal pains, eye diseases and uterine pains. Charaka prescribed the paste of Linseed, castor seeds and shatapushpa (A. graveolens) pounded with milk for external applications in rheumatic and other swellings of joints. Kashyapa samhitaa attributed tonic, rejuvenating and intellect promoting properties to the herb (A. graveolens). It is used in Unani medicine in colic, digestive problem and also in gripe water.[1] Anethum graveolens L. is used in the preparations of more than 56 ayurvedic preparations, which include Dasmoolarishtam, Dhanwanthararishtam, Mrithasanjeevani, Saraswatharishtam, Gugguluthiktaquatham, Maharasnadi kashayam, Dhanwantharam quatham and so on.[2] Anethum graveolens L. (dill) believed to be the native of South-west Asia or South-east Europe.[3] It is indigenous to Mediterranean, southern USSR and Central Asia. Since Egyptian times, Anethum has been used as a condiment and also in medicinal purposes.[4] It was used by Egyptian doctors 5000 years ago and traces have been found in Roman ruins in Great Britain. In the Middle Ages it was thought to protect against witchcraft. Greeks covered their heads with dill leaves to induce sleep.

BOTANICAL DESCRIPTION

Anethum graveolens L. is the sole species of the genus Anethum, though classified by some botanists in the related genus Peucedanum as Peucedanum graveolens (L.).[5] A variant called east Indian dill or Sowa (Anethum graveoeloens var sowa Roxb. ex, Flem.) occurs in India and is cultivated for its foliage as a cold weather crop throughout the Indian sub-continent, Malaysian archipelago and Japan.

Plant description

Anethum grows up to 90 cm tall, with slender stems and alternate leaves finally divided three or four times into pinnate sections slightly broader than similar leaves of fennel. The yellow flower develops into umbels.[6] The seeds are not true seeds. They are the halves of very small, dry fruits called schizocarps. Dill fruits are oval, compressed, winged about one-tenth inch wide, with three longitudinal ridges on the back and three dark lines or oil cells (vittae) between them and two on the flat surface. The taste of the fruits somewhat resembles caraway. The seeds are smaller, flatter and lighter than caraway and have a pleasant aromatic odor.

Cultivation

Dill prefers rich well-drained, loose soil and full sun. It tolerates a pH in the range 5.3 to 7.8. It requires warm to hot summers with huge sunshine levels; even partial shade will reduce the yield substantially. The plant quickly runs into seeds in dry weather. It often self sows when growing in a suitable position. Propagation is through seeds.[5] Seeds are viable for 3–10 years. The seed is harvested by cutting the flower heads off the stalks when the seed is beginning to ripe [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a) Seeds, (b) plants (c) inflorescence

APPLICATIONS

Ecological importance of the species

The herb is a good companion for corn, cabbage, lettuce and onions but inhibits growth of carrots. Dill reduces a carrot crop if it is grown to maturity near them. However, the young plant will help to deter carrot root fly. Sustainable production of fennel and dill by intercropping indicates that the presence of dill exerted a stabilizing effect on fennel seed yield. Insects, bees and wasps are attracted to the yellow flowers of Anethum for plant resources like nectar and pollens. Coriander and dill when planted together has a very remarkable pest control benefits.[7] Intercropping with flowering herbaceous plants increases parasitoid survivorship, fecundity and retention and pest suppression in agro ecosystems. Dill is potentially suitable host for parasitoids, Edovum puttleri Grissell, Cotesia glomerata and Pediobius foveolatus Crawford.[8,9]

Medicinal uses

Anethum is used as an ingredient in gripe water, given to relieve colic pain in babies and flatulence in young children.[5] The seed is aromatic, carminative, mildly diuretic, galactogogue, stimulant and stomachic.[10,11] The essential oil in the seed relieves intestinal spasms and griping, helping to settle colic.[12,13] The carminative volatile oil improves appetite, relieves gas and aids digestion. Chewing the seeds improves bad breath. Anethum stimulates milk flow in lactating mothers, and is often given to cattles for this reason. It also cures urinary complaints, piles and mental disorders.[14]

Other applications and importance

Anethum seeds are used as a spice and its fresh and dried leaves called dill weed are used as condiment and tea. The aromatic herb is commonly used for flavoring and seasoning of various foods such as pickles, salads, sauces and soups.[15,16] Fresh or dried leaves are used for boiled or fried meats and fish, in sandwiches and fish sauces. It is also an essential ingredient of sour vinegar. Dill oil is extracted from seeds, leaves and stems, which contains an essential oil used as flavoring in food industry. It is used in perfumery to aromatize detergents and soaps and as a substitute for caraway oil.[17] Anethum is used as a preservative as it inhibits the growth of several bacteria like Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas. Compounds of dill when added to insecticides have increased the effectiveness of insecticides. Essential oil of A. graveolens L. is used as repellent and toxic to growing larvae and adults of Tribolium castaneum, wheat flour insect pest.[18] In doses of 60 minims, anethole is a fairly potent vermicide for hookworm.[19]

PHARMACOLOGY

Several experimental investigations have been undertaken in diverse in vitro and in vivo models. Some pharmacological effects of Anethum graveolens have been reported such as antimicrobial[14,20,21] antihyperlipidemic and antihypercholesterolemic activities.[22]

Seed extracts of A. graveolens L. have significant mucosal protective, antisecretory and anti-ulcer activities against HCl- and ethanol-induced stomach lesions in mice.[23] Two flavonoids have been isolated from A. graveolens L. seed, quercetin and isoharmentin, which have antioxidant activity and could counteract with free radicals. This effect may help to prevent peptic ulcer.[24,25] Dill fruit hydrochloric extract is a potent relaxant of contractions induced by a variety of spasmogens in rat ileum, so it supports the use of dill fruit in traditional medicine for gastrointestinal disorders.[26] Crude extracts of A. graveolens L. besides having strong anti-hyperlipidemic effects can also improve the biological antioxidant status by reducing lipid peroxidation in liver and modulating the activities of antioxidant enzymes in rats fed with high fat diet.[27]

It has been reported that aqueous extracts of A. graveolens showed a broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. typhimurium, Shigella flexneri and Salmonella typhii.[28] The higher activity of extract can be explained on the basis of the chemical structure of their major constituents such as dillapiole and anethole, which have aromatic nucleus containing polar functional group that is known to form hydrogen bonds with active sites of the target enzyme.[29]

CONSTITUENTS

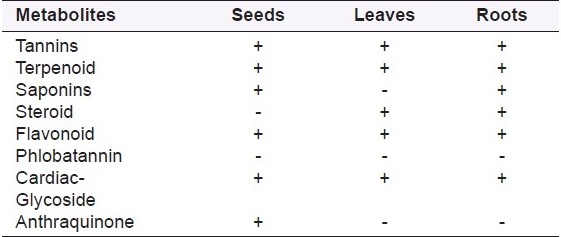

Qualitative phytochemical analysis of the crude powder of plant parts collected was determined as reported in.[30] The phytochemical screening of plant showed that leaves, stems and roots were rich in tannins, terpenoids, cardiac glycosides and flavonoids [Table 1].

Table 1.

Phytochemical analysis of Anethum graveolens L. seeds, leaves and roots

METABOLITES OF IMPORTANCE

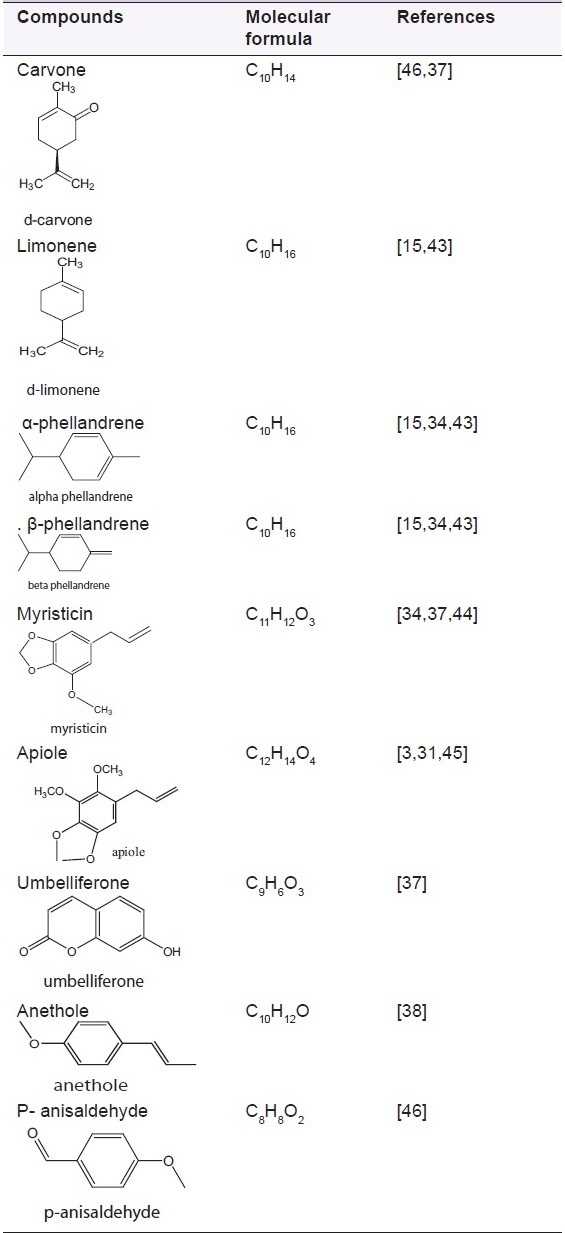

Various different compounds have been isolated from the seeds, leaves and inflorescence of this plant; 17 volatile compounds have been identified. The main constituents of dill oil which is pale yellow in color, darkens on keeping, with the odor of the fruit and a hot, acrid taste are a mixture of a paraffin hydrocarbon and 40 to 60% of d-carvone (23.1%) with d-limonene (45%). It also consists of α-phellandrene, eugenol, anethole, flavonoids, coumarins, triterpenes, phenolic acids and umbelliferones. The fruit yields about 3.5% of the oil; its specific gravity varies between 0.895 and 0.915.

MOLECULES OF INTEREST: CARVONE AND LIMONENE

Carvone and limonene are monoterpenes, which are present as main constituent of dill oil from fruits.[31] α-phellandrene, dill ether and myristicin are the compounds, which form the important odor of dill herb.[15,32] Monoterpenes are 10-carbon members of the isoprenoid family of natural products; they are widespread in the plant kingdom and are often responsible for the characteristic odors of plants. These substances are believed to function principally in ecological roles, serving as herbivore-feeding deterrents, antifungal defenses and attractants for pollinators.[33] Seventeen compounds have been identified in Indian dill leaf.[34] The several applications of carvone are as fragrance and flavor, potato sprouting inhibitor,[35] antimicrobial agent and building block and biochemical environment. D-limonene is one of the most common terpenes in nature. It is a major constituent in several citrus oils (orange, lemon) being an excellent solvent of cholesterol; d-limonene has been used clinically to dissolve cholesterol-containing gallstones. It has chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic activities and also reported to have low toxicity in pre-clinical studies.[36] Myristicin is a naturally occurring insecticide and an important compound of essential oil.[12,37] Anethole is a terpenoid that is present in minor quantity in Anethum, but is also found in essential oil of anise and fennel.[38] It is used as a flavoring substance. p-anisaldehyde has a strong aroma and is an important component in pharmaceuticals and perfumery [Table 2].

Table 2.

Few important compounds found in Anethum are shown

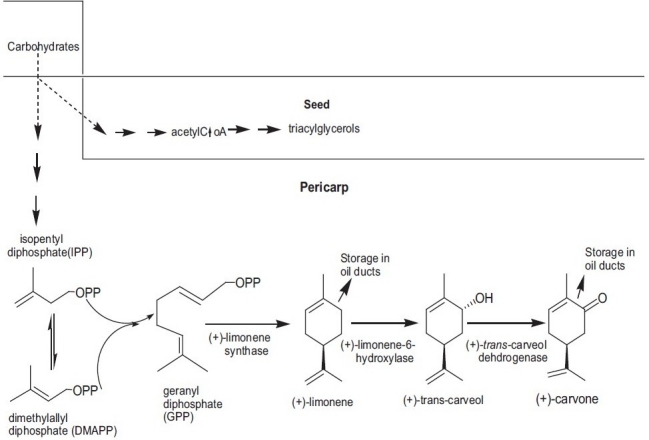

METABOLIC PATHWAY FOR CARVONE SYNTHESIS

The essential oils are primarily composed of mono and sesquiterpenes and aromatic polypropanoids synthesized via the mevalonic acid pathway for terpenes and the shikimic acid pathway for aromatic polypropanoids. The biosynthesis of the monoterpenes limonene and carvone proceeds from geranyl diphosphate via a three-step pathway. First, geranyl diphosphate is cyclized to d-limonene by limonene synthase. Secondly, this intermediate is stored in essential oil ducts without further metabolism or is converted by limonene 6-hydroxylase to trans-carveol. Finally trans-carveol is oxidized by a dehydrogenase to d-carvone[33] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Enzymatic pathway depicting synthesis of limonene and carvone in seeds of Anethum graveolens

CONSERVATION STATUS

To prevent extinction and derive maximum benefits from the indigenous plants of a nation, it is necessary to preserve the germplasm. Due to lack of proper cultivation practices, destruction of plant habitats and illegal and indiscriminate collection of plants from these habitats, many medicinal plants are severely threatened. Anethum seeds are exported to European countries, as they have been used tremendously in flavoring and pharmaceutical industries. Most of the pickle and perfumery industries as well as aromatherapies are highly dependent on the supply of its herb oil and seeds. The International Trade Centre has brought out a material survey of four west European countries (France, UK, The Netherlands and Germany) estimating an overall demand of freeze-dry herb to be less than 300 tonnes per annum to meet its industrial demand.

The plant is propagated through seeds. An increasing interest in the use of efficient protocols for the tissue culture and micropropagation for in vitro production of secondary metabolites and for clonal multiplication of elite genotypes has developed. Sharma et al.[39] have reported a complete protocol on micropropagation of Anethum graveolens L. through axillary shoot proliferation. Sehgal[40] studied the differentiation of shoot buds and embryoids from inflorescence of Anethum graveolens culture, which eventually formed normal plantlets. Very less in vitro research has been performed on this potential plant species. It is cultivated commercially throughout the country and most parts of Europe.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

One of the serious problems in Apiaceae member is low seed set, which is due to the presence of male flowers, underdeveloped flowers and lack of proper pollination and fertilization.[40] Conventional breeding methods have met with limited success in improving this species. Tissue culture techniques used for propagation and conservation of several medicinal plants may prove useful for multiplication and improvement for this species as well.[39,41] The commercial importance of monoterpenes as flavorings, fragrances and pharmaceuticals has stimulated many efforts to increase their yield in plants through in vitro technology. At the same time, with the help of suspension culture, several physiological and biochemical parameters could be analyzed that are still not known in this commercially important plant species. Powerful techniques in plant cell and tissue culture, RDT, bioprocess technologies and so on, coupled with most sophisticated analytical tools such as NMR, HPLC; GC-MS, LC-MS etc. have offered mankind the great potency of exploiting the totipotent biosynthetic and biotransformation capabilities of plant cells under in vitro conditions.[42] Cell and tissue culture techniques of plants provide alternative research material, especially for development and metabolic studies that might be difficult to conduct in intact plants. So there is much scope to enhance the secondary metabolites of this plant.[46]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

G. S. Shekhawat acknowledges financial support from the University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi and Professor Aditya Shastri, Vice chancellor, Banasthali University for his unwavering support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: University Grants Commission, New Delhi.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Khare CP. Indian herbal remedies. Berlin, New York: Springer; 2004. Rational western therapy, ayurvedic and other traditional usages, botany; pp. 60–1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravindran P, Balachandran I. Under utilized medicinal spices II, Spice India. Vol. 17. India: Publisher V K Krishnan Nair; 2005. pp. 32–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailer J, Aichinger T, Hackl G, Hueber KD, Dachler M. Essential oil content and composition in commercially available dill cultivars in comparison to caraway. Indus Crops Prods. 2001;14:229–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quer F. Plantas Medicinales, El Dioscorides Renovado. Barcelona: Editorial labor, S A; 1981. p. 500. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pulliah T. Medicinal Plants in India. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Regency Publications New Delhi; 2002. pp. 55–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warrier PK, Nambiar VPK, Ramakutty C. Arya Vaidya Sala. Vol. 1. Kottakkal Madras, India: Orient Longman Limited; 1994. Indian Medicinal Plants; pp. 153–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrubba A, Torre R, Saiano F, Aiello P. Sustainable production of fennel and dill by intercropping. Agro Sust Develop. 2007;28:247–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patt JM, Hamilton GC, Lashomb JH. Foraging success of parasitoid wasps on flowers: Interplay of insect morphology, floral architecture and searching behavior. Entomol Exp Appl. 1997;83:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wanner H, Gu H, Dorn S. Nutritional value of floral nectar sources for flight in the parasitoid wasp, Cotesia glomerata. Physiol Entomol. 2006;31:127–33. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hornok L. Cultivation and processing of medicinal plants: Academic publications. 1992:338. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma R. Agrotechniques of medicinal plants. New Delhi: Daya Publishing House; 2004. pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duke JA. Handbooke of Medicinal Herbs. London: CRC Press; 2001. p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming T. PDR for Herbal Medicines. New Jersey: Medical Economics Company; 2000. p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair R, Chanda S. Antibacterial activities of some medicinal plants of the western region of India. Turk J Biol. 2007;31:231–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blank I, Grosch W. Evaluation of potent odorants in dill seed anddill herb (Anethum graveolens L.) by aroma extract dilution analysis. J Food Sci. 1991;56:63–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huopalathi R, Linko RR. Composition and content of aroma compounds in dill, Anethum graveolens L., at three different growth stages. J Agri Food Chem. 1983;31:331–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawless J. The illustrated encyclopedia of essential oils. Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element; 1995. p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaubey MK. Insecticidal activity of Trachspermum ammi (Umbelliferae), Anethum graveolens (Umbelliferae) and Nigella sativa (Ranunculaceae) essential oils against stored-product beetle Tribolium castaneum Herbst Coleoptra: Tenebrionidae. Afrin J Agri Res. 2007;2:596–600. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirtikar KP, Basu BD, Mahaskar C. Indian Medicinal Plants. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Allahabad: International Book Distributors; 1987. p. 1219. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaurasia SC, Jain PC. Antibacterial activity of essential oils of four medicinal plants. Indian J Hosp Pharm. 1978;15:166–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delaquis PJ, Stanich K, Girard B, Mazza G. Antimicrobial activity of individual and mixed fractions of dill, cilantro, coriander and eucalyptus essential oils. Int J Food Microbiol. 2002;74:101–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(01)00734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yazdanparast R, Alavi M. Antihyperlipidaemic and antihypercholesterolaemic effects of Anethum graveolens leaves after the removal of furocoumarins. Cytobios. 2001;105:185–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosseinzadeh H, Karimi GR, Ameri M. Effects of Anethum graveolens L. seed extracts on experimental gastric irritation models in mice. BMC Pharmacol. 2002;2:21–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahran GH, Kadry HA, Thabet CK, Al-Azizi M, Liv N. GC/ MS analysis of volatile oil of fruits of Anethum graveolens. Int J Pharmacog. 1992;30:139–44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohele B, Heller W, Wellmann E. UV-induced biosynthesis of quercetin 3-o-beta-d-glucuronide in dill Anethum graveolens cell cultures. Phytochem. 1985;24:183–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naseri-Gharib MK, Heidari A. Antispasmodic effect of A. graveolens fruit extract on rat ileum. Int J Pharm. 2007;3:260–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yazdanparast R, Bahramikia S. Improvement of liver antioxidant status in hypercholesterolamic rats treated with A.graveolens extracts. Pharmacologyonline. 2007;3:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arora DS, Kaur JG. Antibacterial activity of some Indian medicinal plants. J Nat Med. 2007;61:313–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farag RS, Daw ZY, Abo-Raya SH. Influence of some spice essential oils on Aspergillus parasiticus growth and production of aflatoxin in a synthetic medium. J Food Sci. 1989;54:74–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aiyelaagbe OO, Osamudiamen PM. Phytochemical screening for active compounds in Mangifera indica leaves from Ibadan, Oyo state. Plant Sci Res. 2009;2:11–3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos AG, Figueiredo AC, Lourenco PM, Barrosa JG, Pedro LG. Hairy root cultures of Anethum graveolens (dill): Establishment, growth, time-course study of their essential oil and its comparison with parent plant oils. Biotech Lett. 2002;24:1031–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonnlander B, Winterhalter P. 9-Hydroxypiperitone beta-D-glucopyranoside and other polar constituents from dill (Anethum graveolens L.) herb. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:4821–5. doi: 10.1021/jf000439a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouwmeester HJ, Gershenzon J, Konings MC, Croteau R. Biosynthesis of the monoterpenes limonene and carvone in the fruit of caraway. I. Demonstration Of enzyme activities and their changes with development. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:901–12. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.3.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raghvan B, Abrahman KO, Koller WD, Shankarnarayanan ML. Studies on flavor changes during drying of Dill (Anethum sowa. Roxb) leaves. J Food Qual. 1994;17:457–66. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Score C, Lorenzi R, Ranall P. The effect of S- (+)-carvone treatments on seed potato tuber dormancy and sprouting. Potato Res. 1997;40:155–61. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vigushin DM, Poon GK, Boody A, English J, Halbert GW, Pagonis C, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of D-limonene in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Research Campaign Phase I/II Clinical Trials Committee. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42:111–7. doi: 10.1007/s002800050793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dhalwal K, Shinde VM, Mahadik KR. Efficient and sensitive method for quantitative determination and validation of Umbelliferone, carvone and Myristicin in Anethum graveolens and Carum carvi seeds. Chromatograph. 2008;67:163–7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newberne P, Smith RL, Doull J, Goodman JI, Munro IC, Portoghese PS, et al. The FEMA GRAS assessment of trans-anethole used as a flavoring substance. Flavor and Extract Manufacturer's Association. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:789–811. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma RK, Wakhlu AK, Boleria M. Micropropagation of Anethum graveolens L. through axillary shoots proliferation. J Plant Biochem Biotech. 2004;13:157–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sehgal CB. Differentiation of shoot buds and embryoids from inflorescence of Anethum graveolens in cultures. Phytomorphol. 1978;28:291–7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta R. Studies in cultivation and improvement of dill (Anethum graveolens) in India. In: Atal CK, Kapur BM, editors. Jammu: In Cultivation and Utilization of Medicinal and Aromatic plants, Regional Research Laboratory; pp. 545–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stockigt J, Obitz P, Fakenghegen H, Lutterbach R, Endress S. The natural product and enzymes from plant cell culture. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1985;43:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blank I, Sen A, Grosch W. Sensory study on the character-impact flavour compounds of dill herb (Anethum graveolens L.) Food Chem. 1992;43:337–43. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee BK, Kim JH, Jung JW, Choi JW, Han ES, Lee SH, et al. Myristicin-induced neurotoxicity in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. Toxicol Lett. 2005;157:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shulgin AT, Sargent T. Psychotropic phenylisopropylamines derived from apiole and dillapiole. Nature. 1967;215:1494–5. doi: 10.1038/2151494b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh G, Maurya S, Lampasona MP, Catalan C. Chemical constituents, antimicrobial investigations, and antioxidative potentials of Anethum graveolens L. essential oil and acetone extract: Part 52. J Food Sci. 2005;70:208–15. [Google Scholar]