Abstract

Herbs have always been the principal form of medicine in India. Medicinal plants have curative properties due to the presence of various complex chemical substances of different composition, which are found as secondary plant metabolites in one or more parts of these plants. Ficus religiosa (L.), commonly known as pepal belonging to the family Moraceae, is used traditionally as antiulcer, antibacterial, antidiabetic, in the treatment of gonorrhea and skin diseases. F. religiosa is a Bo tree, which sheltered the Buddha as he divined the “Truths.” The present review aims to update information on its phytochemistry and pharmacological activities.

Keywords: Antibacterial, antidiabetic, antiulcer, ficus religiosa (L.), pharmacological activities, phytochemistry

INTRODUCTION

Ficus religiosa (L.) is a large perennial tree, glabrous when young, found throughout the plains of India upto 170m altitude in the Himalayas, largely planted as an avenue and roadside tree especially near temples.[1] It is a popular bodhi tree and has got mythological, religious, and medicinal importance in Indian culture since times immemorial.[2] The plants have been used in traditional Indian medicine for various range of ailments. Traditionally the bark is used as an antibacterial, antiprotozoal, antiviral, astringent, antidiarrhoeal, in the treatment of gonorrhea, ulcers, and the leaves used for skin diseases. The leaves reported antivenom activity and regulates the menstrual cycle.[3,4] In Bangladesh, it has been used in the treatment of various diseases such as cancer, inflammation, or infectious diseases.[5] In case of high fever, its tender branches are used as a toothbrush. Fruits are used as laxatives,[6] latex is used as a tonic, and fruit powder is used to treat asthma.[7,8]

BOTANICAL DESCRIPTION

Taxonomy

Domain: Eukaryota

Kingdom: Plantae

Subkingdom: Viridaeplantae

Phylum: Tracheophyta

Subphylum: Euphyllophytina

Infraphylum: Radiatopses

Class: Magnoliopsida

Subclass: Dilleniidae

Superorder: Urticanae

Order: Urticales

Family: Moraceae

Tribe: Ficeae

Genus: Ficus

Specific epithet: Religiosa Linnaeus

Botanical name : Ficus religiosa

Vernacular names

Sanskrit: Pippala

Assamese: Ahant

Bengali: Asvattha, Ashud, Ashvattha

English: Pipal tree

Gujrati: Piplo, Jari, Piparo, Pipalo

Hindi: Pipala, Pipal

Kannada: Arlo, Ranji, Basri, Ashvatthanara, Ashwatha, Aralimara, Aralegida, Ashvathamara, Basari, Ashvattha

Kashmiri: Bad

Malayalam: Arayal

Marathi: Pipal, Pimpal, Pippal

Oriya: Aswatha

Punjabi: Pipal, Pippal

Tamil: Ashwarthan, Arasamaram, Arasan, Arasu, Arara

Telugu: Ravichettu

Morphological characters

This big and old tree is of 30m long. They shatter bark and are of white or brown in color. The leaves are shiny, thin, and bear 5–7 veins. Fruits are small, about ½ inch in diameter, similar to that of eye pupil. It is circular in shape and compressed. When it is raw, it is of green color and turns black when it is ripe. The tree fruits in summer and the fruits get ripened by rainy season.

The leaves show more or less sigmoid growth pattern, each leaf increases in size in 9 days from about 425 to 4025mm2 (as judged by the average mature leaf size) after its emergence from the spathe. The leaf is hypostomatic and has paracytic and anomocytic stomata between polygonal epidermal cells. The frequency of stomata per square millimeter increases from 33.3 to 400 per mm2 with the growth of the leaves, while the number of upper epidermal cells decreases from 5600 to 1110. The vasculature comprises a single main vein (the midrib), secondaries, tertiaries, quaternaries, and intermediaries. The number of areoles per square millimeter decreases from 15.5 to 2.7, while the number of vein endings and vein tips per areole show no correlation either with one another or with leaf size.[9]

PHYTOCHEMISTRY

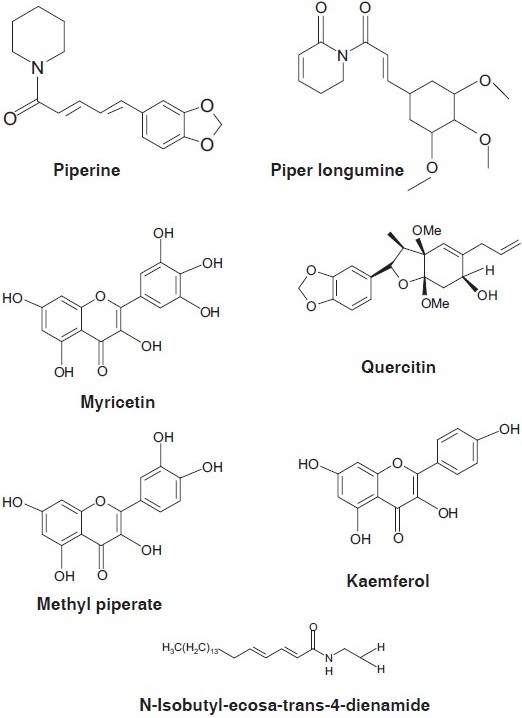

The stem bark of F. religiosa are reported phytoconstituents of phenols, tannins, steroids, alkaloids and flavonoids, β-sitosteryl-D-glucoside, vitamin K, n-octacosanol, methyl oleanolate, lanosterol, stigmasterol, lupen-3-one.[10] The active constituent from the root bark F. religiosa was found to be β-sitosteryl-D-glucoside, which showed a peroral hypoglycemic effect in fasting and alloxan-diabetic rabbits and in pituitary-diabetic rats. The fruits contain 4.9% protein having the essential amino acids, isoleucine, and phenylalanine.[11] The seeds contain phytosterolin, β-sitosterol, and its glycoside, albuminoids, carbohydrate, fatty matter, coloring matter, caoutchoue 0.7–5.1%.[12] F. religiosa fruits contain flavonols namely kaempeferol, quercetin, and myricetin [Figure 1].[13] Leaves and fruits contain carbohydrate, protein, lipid, calcium, sodium, potassium, and phosphorus.[14] The aqueous extract of dried bark of F. religiosa has been reported to contain phytosterols, flavonoids, tannins, furanocoumarin derivatives namely bergapten and begaptol.

Figure 1.

Phytoconstituents of F. religoisa

The fruit of F. religiosa contained appreciable amounts of total phenolic contents, total flavonoid, and percent inhibition of linoleic acid. Generally higher extract yields, phenolic contents, and plant material antioxidant activity were obtained using aqueous organic solvents, as compared to the respective absolute organic solvents. Although higher extract yields were obtained by the refluxing extraction technique, in general higher amounts of total phenolic contents and better antioxidant activity were found in the extracts prepared using a shaker.[15]

PHARMACOLOGY

Antibacterial activity

Aqueous and ethanolic extracts of F. religiosa leaves showed antibacterial effect against Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella paratyphi, Shigella dysenteriae, S. typhimurium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtillis, S. aureus, Escherichia coli, S. typhi.[16–18] In another study, chloroform extract of fruits showed antimicrobial effect against Azobacter chroococcum, Bacillus cereus, B. megaterium, Streptococcus faecalis, Streptomycin lactis, and Klebsiella pneumonia.[17] The ethanolic extract of leaves showed antifungal effect against Candida albicans.[18] Aqueous, methanol, and chloroform extracts from the leaves of F. religiosa were completely screened for antibacterial and antifungal activities. The chloroform extract of F. religiosa possessed a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity with a zone of inhibition of 10–21mm. The methanolic extracts possessed moderate antibacterial activity against a few bacterial strains. There was less antibacterial activity or none at all using aqueous extracts. The extracts of F. religiosa were found to be active against Aspergillus niger and Penicillium notatum. The extracts from the leaves exhibited considerable and variable inhibitory effects against most of the microorganisms tested.[18,19]

Anthelmintic activity

F. religiosa bark methanolic extract was 100% lethal for Haemonchus contortus worms.[20] The stem and bark extracts of F. religiosa proved lethal to Ascaridia galli in vitro. The latex of some species of Ficus (Moraceae), i.e., Ficus inspida, F. carica was also reported to have anthelmintic activity against Syphacia obvelata, Aspiculuris tetraptera, and Vampirolepis nana.[21] The pharmacological studies on F. glabrata latex with live Ascaris demonstrated a lethal effect at concentrations reduced to 0.05% latex in physiological saline solution. It has been accepted that anthelmintic activity is due to a proteolytic fraction called ficin. It is evident from above that methanolic extracts of F. religiosa possibly exerted anthelmintic effect because of ficin.[22]

Immunomodulatory activity

The immunomodulatory effect of alcoholic extract of the bark of F. religiosa (moraceae) was investigated in mice. The study was carried out by various hematological and serological tests. Administration of extract remarkably ameliorated both cellular and humoral antibody response. It is concluded that the extract possessed promising immunostimulant properties.[23]

Antioxidant activity

The literature showed that the antioxidative properties of the extract of F. religiosa fruit and bark were done using different solvents. They were evaluated on the basis of oil stability index together with their radical scavenging ability against 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH).[24] The oxidative stress and oxidative damage to tissues are common end points of chronic diseases such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Oxidative stress in diabetes coexists with a reduction in the antioxidant status, which can further increase the deleterious effects of free radicals. The aqueous extract of F. religiosa reduces oxidative stress in experimentally induced type 2 diabetes rats. Type 2 diabetic rats gained relatively less weight during the course of development as compared to normal rats. Decrease in uptake of glucose, free fatty acids from circulation, and accelerated β-oxidation in adipose tissue lead to weight loss in diabetes. The aqueous extract of F. religiosa improved the body weight of diabetic rats.[25]

Aqueous extract of F. religiosa modulated the superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in the diabetic rats dose dependently and also decreased catalase (CAT) activity. It could be possible due to less availability of NADPH or gradual decrease in erythrocyte CAT concentration by excessive generation of O2++ inactivates the enzyme. Since the activity of an enzyme depends upon its substrate, depletion of glutathione (GSH) may be the reason for decreased glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity. Aqueous extract of F. religiosa bark had upregulated the CAT and GSH-Px activities. Drug at higher dose (200 mg/kg) was better effective in modulating the enzyme.[26]

The methanolic extract of F. religiosa leaf inhibits the production of nitric oxide and proinflammatory cytokines in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated microglia via the mitogen activation protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by using cell viability assay, nitric oxide assay, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The extract exerts strong anti-inflammatory properties in microglial activation. It is likely that extract has a neuroprotective effect against inflammation by inflammatory mediators such as nitric oxide and cytokines.[27]

Recently, the methanolic extract of F. religiosa has been reported to have neurotrophic effects and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity.[28]

Wound-healing activity

The effect of hydroalcoholic extract of F. religiosa leaves on experimentally induced wounds in rats using different wound models results in dose-dependent wound-healing activity in excision wound, incision wound, and burn wound. A formulation of leaves extract was prepared in emulsifying ointment at a concentration of 5% and 10% and applied to the wounds. In excision wound and burn wound models, the extract showed significant decrease in the period of epithelization and in wound contraction (50%). A significant increase in the breaking strength was observed in an incision wound model when compared to the control. The result suggests that leaf extract of F. religiosa (both 5% and 10%) applied topically possess dose-dependent wound-healing activity.[29]

Anticonvulsant activity

Methanolic extract of figs of F. religiosa had anticonvulsant activity against maximum electroshock (MES) and picrotoxin-induced convulsions, with no neurotoxic effect, in a dose-dependent manner. F. religiosa extract showed a significant protection in MES and picrotoxin-induced convulsion models in a dose-dependent manner. There was a significant decrease in the duration of tonic hind limb extension at all the three doses of extract (25, 50, and 100mg/kg) in MES model with maximum protection observed at 100mg/kg dose, as compared to control group. The anticonvulsant activity of the extract at 100mg/kg was found to be comparable to phenytoin-treated group; similarly, treatment with extract caused a dose-dependent delay of the latency to clonic convulsions in picrotoxin-induced convulsion model. However significant increase in the latency to clonic convulsions was observed only at 50 and 100mg/kg dose of extract as compared to control group. F. religiosa extract increased the threshold of MES and picrotoxin-induced convulsions with no neurotoxic effects, in a dose-dependent manner. Inhibition of antiepileptic effect of extract by cyproheptadine pretreatment showed that the extract might be mediating its effect via modulating serotonin-dependent GABAergic and/or glutamatergic neurotransmission.[30]

Hypolipidemic activity

Dietary fiber content of food namely peepalbanti (F. religiosa), cellulose, and lignin were predominating constituents in peepalbanti, fed at 10% dietary level to rats, induced a greater resistance to hyperlipidemia than cellulose. Teent had the most pronounced hypocholesterolemic effect that appeared to operate through increased fecal excretion of cholesterol as well as bile acids. Dietary hemicellulose showed a significant negative correlation with serum and liver cholesterol and a significant positive correlation with fecal bile acids. The dietary fiber influenced total lipids, cholesterol, triglycerides, and phospholipids of the liver to varying extents.[31]

Hypoglycemic activity

β-Sitosterol-D-glycoside was isolated from the root bark of F. glomerata and F. religiosa, which has a peroral hypoglycemic activity.[32] Oral administration of F. religiosa bark extract at the doses of 25, 50, and 100mg/kg was studied in normal, glucose-loaded, and STZ (streptozotocin) diabetic rats. The three doses of bark extract produced significant reduction in blood glucose levels in all the models. The effect was more pronounced in 50 and 10mg/kg than 25mg/kg. F. religiosa also showed significant increase in serum insulin, body weight, and glycogen content in liver and skeletal muscle of STZ-induced diabetic rats, while there was significant reduction in the levels of serum triglyceride and total cholesterol. F. religiosa also showed significant antilipid peroxidative effect in the pancreas of STZ-induced diabetic rats. The results indicate that aqueous extract of F. religiosa bark possesses significant antidiabetic activity.[33]

CONCLUSION

Medicinal plants are the local heritage with the global importance. World is endowed with a rich wealth of medicinal plants. Medicinal plants also play an important role in the lives of rural people, particularly in remote parts of developing countries with few health facilities. The present review reveals that F. religiosa contains several phytoconstituents like β-sitosteryl-D-glucoside, vitamin K, n-octacosanol, kaempeferol, quercetin, and myricetin. The plant has been studied for their various pharmacological activities like antibacterial, antifungal, anticonvulsant, immunomodulatory, antioxidant, hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, anthelmintics, and wound healing activities.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Ministry of health and family welfare, department of Ayush. New Delhi: 2001. Ayurvedic pharmacopeia of India; pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasad PV, Subhakthe PK, Narayana A, Rao MM. Medico historical study of “asvattha” (sacred fig tree) Bull Indian Inst Hist Med Hyderabad. 2006;36:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalpana G, Rishi RB. Ethnomedicinal Knowledge and healthcare practices among the Tharus of Nwwalparasi district in central Nepal. For Ecol Manage. 2009;257:2066–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra RN, Chopra S. Indigenous Drugs of India. 2nd ed. Calcutta: Dhur and Sons; 1958. p. 606. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uddin SJ, Grice ID, Tiralongo E. Cytotoxic effects of Bangladeshi medicinal plant extracts. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2009 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep111. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah NC. Herbal folk medicines in northern India. J Ethnopharmacol. 1982;6:293–301. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(82)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh AK, Raghubanshi AS, Singh JS. Medical ethnobotany of the tribals of sonaghati of sonbhadra district, uttat Pradesh, India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;81:31–41. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ananda RJ, Kunjani J. Indigenous knowledge and uses of medicinal plants by local communities of the kali Gandaki Watershed Area, Nepal. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73:175–83. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sajwan VS, Nilima H, Paliwal GS. Developmental anatomy of the leaf of L.Ficus religiosa. Ann Bot. 1977;41:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheetal A, Bagul MS, Prabia M, Rajani M. Evaluation of free radicals scavenging activity of an Ayurvedic formulation, panchvankala. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70:31–8. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.40328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliver bever B. Oral hypoglycaemic plants in West Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 1977;2:119–27. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(80)90005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khare CP. Encyclopedia of Indian medicinal plants. Berlin Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2004. pp. 50–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushra S, Farooq A. Flavonols (kaempeferol, quercetin, myricetin) contents of selected fruits, vegetables and medicinal plants. Food Chem. 2008;108:879–84. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruby J, Nathan PT, Balasingh J, Kunz TH. Chemical composition of fruits and leaves eaten by short- nosed fruit bat, Cynopterus sphinx. J Chem Ecol. 2000;26:2825–41. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swami KD, Bisht NP. Constituents of Ficus religiosa and Ficus infectoria and their biological activity. J Indian Chem Soc. 1996;73:631. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valsaraj R, Pushpangadan P, Smitt UW, Adersen A, Nyman U. Antimicrobial screening of selected medicinal plants from India. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;58:75–83. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mousa O, Vuorela P, Kiviranta J, Abdelwahab S, Hiltunen R, Vuorela H. Bioactivity of certain Egyptian Ficus species. J Ethnopharmacol. 1994;41:71–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrukh A, Iqbal A. Broad-spectrum antibacterial and antifungal properties of certain traditionally used Indian medicinal plant. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;19:653–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemaiswarya S, Poonkothai M, Raja R, Anbazhagan C. Comparative study on the antimicrobial activities of three Indian medicinal plants. Egypt J Biol. 2009;11:52–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaushik RK, Katiyar JC, Sen AB. A new in vitro screening technique for anthelmintic activity using Ascaridia galli as a test parasite. Indian J Anim Sci. 1981;51:869–72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Amorin A, Borba HR, Caruta JP, Lopes D, Kaplan MA. Anthelmintic activity of the latex of Ficus species. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;64:255–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansson A, Veliz G, Naquira C, Amren M, Arroyo M, Arevalo G. Preclinical and clinical studies with latex from Ficus glabrata HBK, a traditional intestinal anthelmintic in the Amazonian area. J Ethnopharmacol. 1986;17:105–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallurvar VR, Pathak AK. Studies on immunomodulatory activity of Ficus religiosa. [last cited on 2010 Mar 7];Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2008 42(4):343–347. Available from: http://www.openjgate.com/Browse/ArticleList.aspx?Journal_id=106495andissue_id=967114 . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bushra S, Muhraf FA. Effect of extraction solvent/Technique on the antioxidant activity of selected medicinal plant extracts. Molecules. 2009;14:2168–80. doi: 10.3390/molecules14062167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.You T, Nicklas BJ. Chronic inflammation: Role of adipose tissue and modulation by weight loss. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2006;2:29–37. doi: 10.2174/157339906775473626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirana H, Agrawal SS, Srinivasan BP. Aqueous extract of Ficus religiosa Linn: Reduces oxidative stress in experimentally induced type 2 diabetic rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 2009;47:822–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyo WJ, Hye YS, Chau V, Young HK, Young KP. Methnol extract of Ficus leaf inhibits the production of nitric oxide and Proinflammatory cytokines in LPS stimulated microglia via the MAPK pathway. Phytother Res. 2008;22:1064–9. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinutha B, Prashanth D, Salma K. Screening of selected Indian medicinal plants for acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;109:359–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naira N, Rohini RM, Syed MB, Amit KD. Wound healing activity of the hydro alcoholic extract of Ficus religiosa leaves in rats. [last cited on 2010 Mar 7];Internet J Altern Med. 2009 6:2–7. Available from: http://www.britannica.com/bps/additionalcontent/18/36006174/Woundhealing . [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damanpreet S, Rajesh KG. Anticonvulsant effect of Ficus religiosa: Role of serotonergic pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123:330–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agarwal V, Chauhan BM. A study on composition and hypolipidemic effect of dietary fibre from some plant foods. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1988;38:189–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01091723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ambike S, Rao M. Studies on a phytosterolin from the bark of Ficus religiosa. Indian J Pharm. 1967;29:91–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panit R, Phadke A, Jagtap A. Antidiabetic effect of Ficus religiosa extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:462–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]