Abstract

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is the best-known allergic manifestation of Aspergillus-related hypersensitivity pulmonary disorders. Most patients present with poorly controlled asthma, and the diagnosis can be made on the basis of a combination of clinical, immunological, and radiological findings. The chest radiographic findings are generally nonspecific, although the manifestations of mucoid impaction of the bronchi suggest a diagnosis of ABPA. High-resolution CT scan (HRCT) of the chest has replaced bronchography as the initial investigation of choice in ABPA. HRCT of the chest can be normal in almost one-third of the patients, and at this stage it is referred to as serologic ABPA (ABPA-S). The importance of central bronchiectasis (CB) as a specific finding in ABPA is debatable, as almost 40% of the lobes are involved by peripheral bronchiectasis. High-attenuation mucus (HAM), encountered in 20% of patients with ABPA, is pathognomonic of ABPA. ABPA should be classified based on the presence or absence of HAM as ABPA-S (mild), ABPA-CB (moderate), and ABPA-CB-HAM (severe), as this classification not only reflects immunological severity but also predicts the risk of recurrent relapses.

Keywords: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, aspergillus, chest radiograph, computed tomography, High-resolution CT scan

Introduction

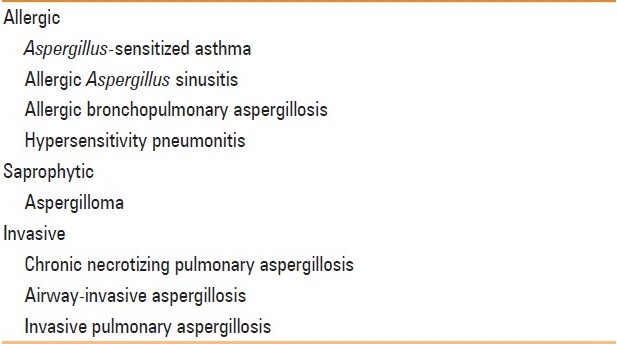

The clinical, radiological, and histological manifestations of bronchopulmonary aspergillosis depend not only on the number and virulence of the infective organism but also on the patient's immune response.[1] Depending on these factors, the disease can be classified as saprophytic, allergic, and invasive [Table 1].[2,3] Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), the most widely studied Aspergillus-related allergic phenomenon, is an immune-mediated inflammatory syndrome caused by hypersensitivity to a ubiquitous fungus, Aspergillus fumigatus.[4] On the other hand, allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis (ABPM) is an ABPA-like syndrome due to fungal organisms other than A. fumigatus. The frequency of ABPM is negligible compared to that of ABPA.[5]

Table 1.

Spectrum of pulmonary disorders caused by Aspergillus species

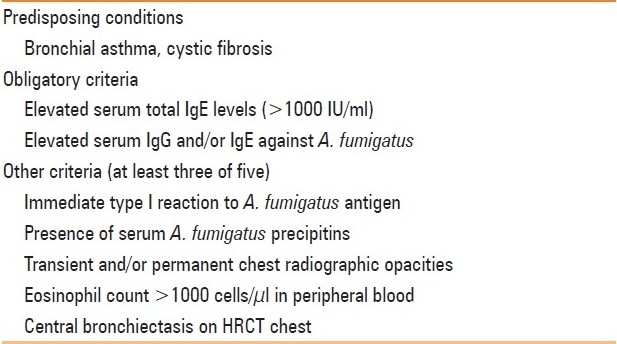

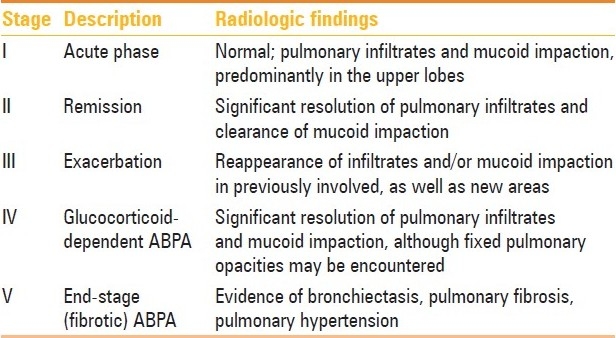

ABPA most commonly complicates the course of bronchial asthma and cystic fibrosis (CF).[6] This review deals only with ABPA in bronchial asthma. The clinical presentation of ABPA is usually with poorly controlled asthma, hemoptysis, expectoration of mucus plugs, malaise, and fever. The diagnosis can be made on the basis of a combination of clinical, immunological, and radiological findings [Table 2],[7] which can easily be remembered using the mnemonic ARTSPICE (Asthma, Radiographic opacities, Type I skin test against Aspergillus antigen, Specific A. fumigatus IgG and IgE levels elevated, Precipitins against A. fumigatus, IgE levels raised, Central bronchiectasis, and Eosinophilia).[7] ABPA has also been classified into five stages, although the patient need not necessarily pass through these stages in a sequential fashion [Table 3].[8] The condition was first described in 1952 from the United Kingdom by Hinson et al.[9] Even after five decades of research the disorder is still underdiagnosed, with as many as one-third of cases being initially misdiagnosed as pulmonary tuberculosis in the developing countries.[10] The fact is that the disorder is glucocorticoid-sensitive and early diagnosis and treatment can halt the development of bronchiectasis and end-stage fibrosis.[11] Most patients present with bronchiectasis, which is a manifestation of end-stage lung disease. Radiological investigations are used to establish the initial diagnosis of ABPA and to assess the pathologic sequel at different stages of the disease. This article reviews the chest radiographic and CT scan features of ABPA.

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis[7]

Table 3.

Methodology

For the purpose of this review, we performed a systematic search of the electronic databases PubMed and EmBase to identify relevant studies published literature from 1952 to 2011 using the free-text terms: “allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis” and “ABPA.” A total of 100 papers were identified and reviewed for this article.

Chest Radiographic Findings

Radiological findings are nonspecific or subtle in the early stages of the disease, and the diagnosis is often difficult.[12–15]

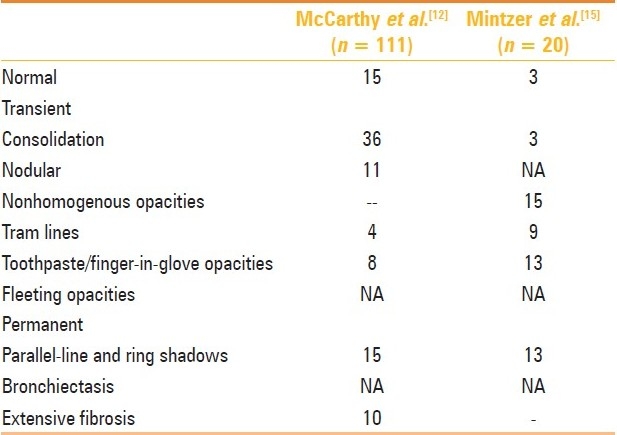

There is preferential involvement of the upper lobes. Mendelson et al. described the chest radiographic findings in various stages of ABPA [Table 3].[16] The chest radiographic appearances of ABPA are myriad, and can be broadly classified as transient and permanent [Table 4]. In our experience, the chest radiograph is normal in almost 50% of the cases.

Table 4.

Radiographic findings in the first chest radiograph in cases of ABPA

Transient Changes

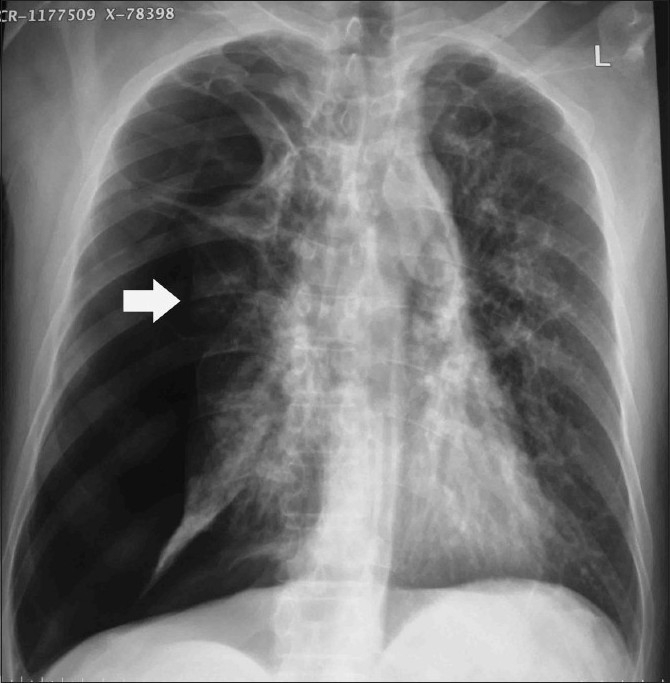

The active stage is characterized radiographically by transient and recurrent infiltrates that may clear with or without glucocorticoid therapy, although steroid therapy does hasten the clearing of opacities [Figure 1]. Consolidation is believed to be one of the most common findings, and the occurrence of eosinophilic pneumonia has also been pathologically demonstrated.[12] Massive consolidation was present in 71% of the 111 cases of ABPA described by McCarthy et al.[12] However, this report is from the pre-CT scan era. In our experience, while consolidation does occur in patients with acute exacerbation, it is not as common as mucoid impaction of the bronchi. Pulmonary masses in ABPA can occur via three mechanisms, namely, mucus plugging of bronchi with distal accumulation of secretions, formation of large bronchoceles (mucus-filled dilated bronchi) without any proximal obstruction, and eosinophilic parenchymal consolidation without endobronchial involvement.[17] In fact, many cases of consolidation are revealed to be large areas of mucus-filled bronchi on the CT chest [Figure 2].[17]

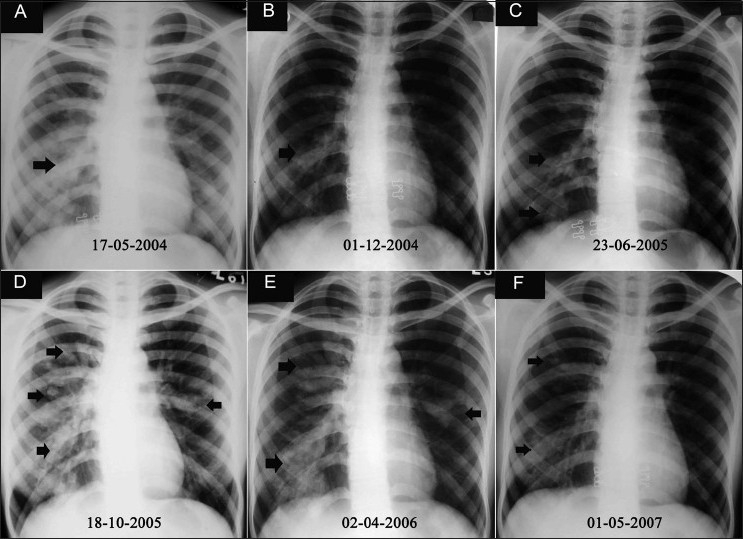

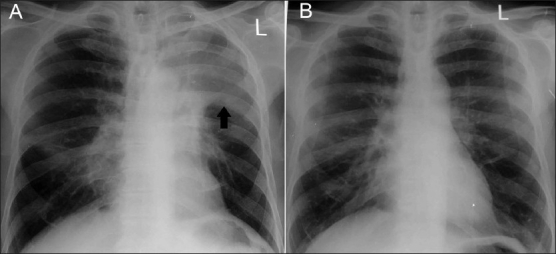

Figure 1.

(A-F): Serial chest radiographs over 3 years in a patient of ABPA show typical fleeting opacities (arrows) involving different areas of the lung. The patient received multiple courses of antituberculous therapy without any relief of symptoms

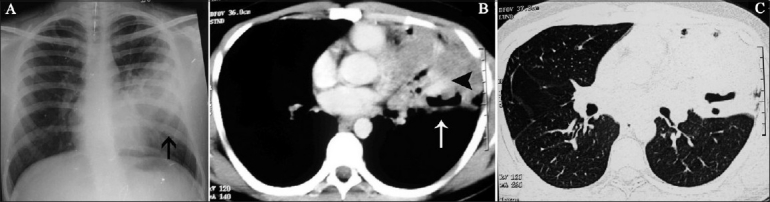

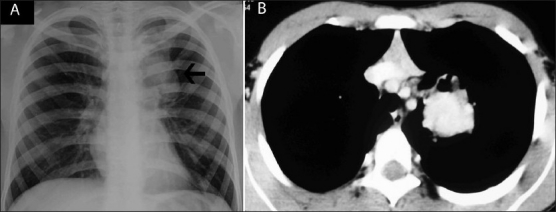

Figure 2.

(A-C): Patient of ABPA during an acute exacerbation. Chest radiograph (A) shows left mid- and lower-zone consolidation (arrow). Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan in soft issue (B) and lung (C) windows shows mucoid impaction with hyperdense mucus content (arrowhead), and lobar collapse (arrow)

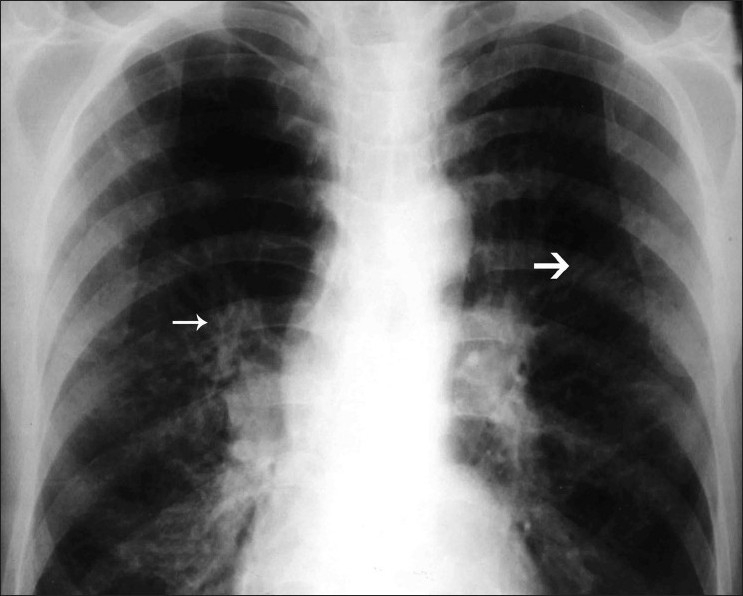

Tram-line shadows[12], band-like (toothpaste) shadows[12,14,15] showing sometimes “V,” inverted “V,” or “Y” shaped shadows [Figure 3].[14] and finger-in-glove opacities [Figure 4] may occur. They are the most characteristic finding of ABPA and represent mucoid impaction in dilated bronchi with occlusion of the distal end. These shadows are often transient, disappearing with the expulsion of secretions either spontaneously or following treatment. Transient air-fluid levels may be seen in dilated bronchi. In some instances, the dilated bronchus is filled completely with allergic mucin and appears as a circular shadow. Atelectasis is identified as a homogeneous shadow with fissure displacement. It is usually segmental and occasionally lobar [Figure 5].

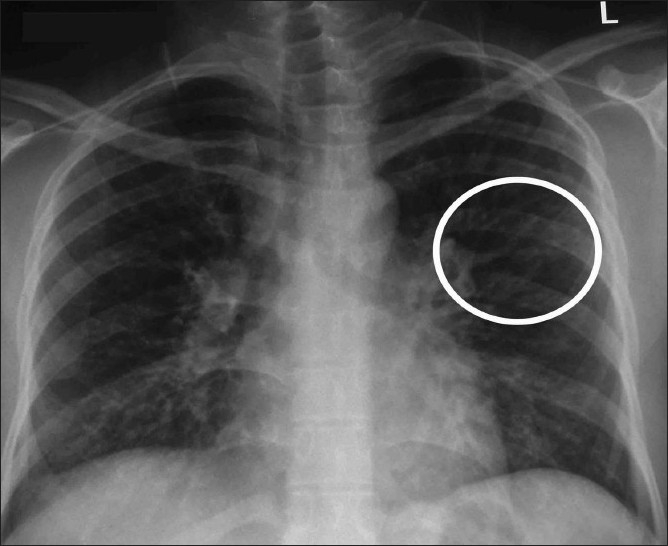

Figure 3.

Chest radiograph shows a “Y-shaped” opacity (circle) that represent mucus-filled bronchi

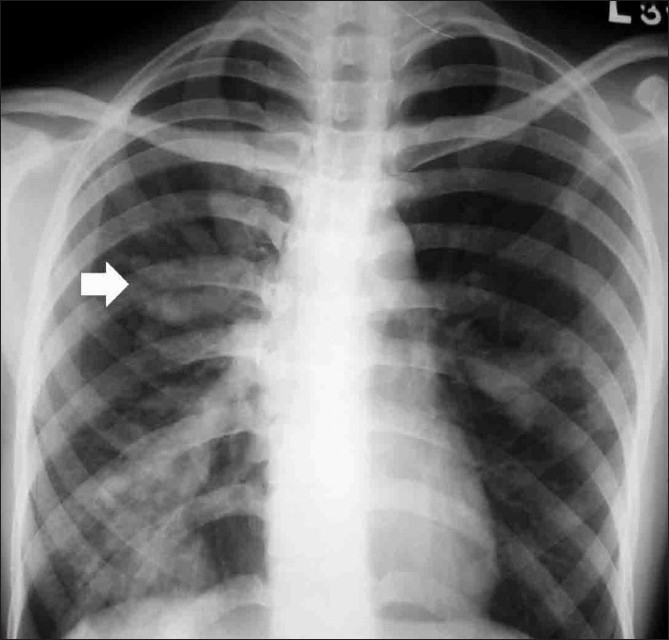

Figure 4.

Chest radiograph shows mucoid impaction with the classic finger-in-glove pattern (arrow)

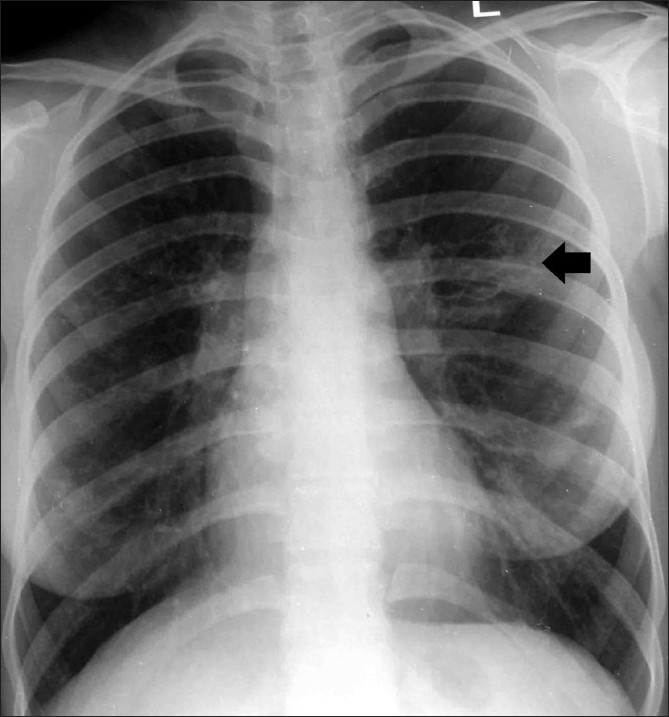

Figure 5 (A, B).

Chest radiograph at presentation (A) shows left upper lobe collapse (arrow) that cleared (B) after treatment with glucocorticoids

Perihilar opacities simulating hilar/mediastinal lymphadenopathy (also referred to as pseudohilar opacities) occur due to the presence of mucus-filled, dilated, central bronchi close to the hilum or mediastinum [Figure 6].[15,18–21] Rarely, true hilar adenopathy (which resolves on therapy) has also been reported in ABPA.[22,23] This lymphadenopathy is probably reactive hyperplasia of the lymphoid tissue, which disappears following therapy. We have also recently reported a rare occurrence of miliary nodular opacities in a case of ABPA, which responded to steroid therapy.[24]

Figure 6 (A, B).

Chest radiograph (A) of a proven case of ABPA shows a left paratracheal opacity (arrow). Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan confirmed this opacity to be a bronchocele with high attenuation mucus in the left suprahilar region

Permanent Changes

Parallel-line shadows are similar to tram-line shadows but the width of the zone between the lines is more than that of a normal bronchus and represent a dilated bronchus [Figure 7]. Transient toothpaste shadows can disappear due to expectoration of the sputum plug within the bronchi and leave behind a parallel-line shadow. Ring shadows are circular hair-line shadows about 1–2 cm in diameter that represent dilated bronchi. Occasionally numerous ring shadows representing multiple dilated bronchi can be observed [Figure 8]. Patients with end-stage disease may present with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax [Figure 9].

Figure 7.

Chest radiograph shows the presence of tram-line (thick arrow) and parallel-line (thin arrow) shadows

Figure 8.

Chest radiograph shows central bronchiectasis (arrow) in the left mid-zone

Figure 9.

Chest radiograph of a patient with end-stage fibrotic ABPA who presented with a right-sided spontaneous pneumothorax (arrow)

CT Scan Findings

Plain chest radiography is not sufficiently sensitive to assess the extent of bronchiectasis.[25] Bronchography has been traditionally considered the investigation of choice for the diagnosis of bronchiectasis. On the bronchogram, a characteristic pattern of proximal bronchial dilatation with normal peripheral filling is observed in ABPA.[14,15,26] However, bronchography is invasive, relatively contraindicated in asthma, and may be associated with adverse effects.[16] HRCT of the chest is safe, allows better assessment of the pattern and distribution of bronchiectasis, and also detects abnormalities that are not apparent on chest radiography. Moreover, it has been seen that the HRCT appearance of the parenchymal abnormalities reflects the macroscopic pathologic findings.[27]

Utility of CT Scan in Diagnosis of Bronchiectasis

The diagnostic utility of CT scan depends on the protocol followed for image acquisition. Conventional CT scan used in the past is neither as sensitive as bronchography,[28–31] nor does it demonstrate all forms of bronchiectasis.[32,33]

As compared to bronchography, HRCT (1-1.5 × 5-15 mm) of the chest has a sensitivity and specificity of 96%–98% and 93%–99%, respectively, in the diagnosis of bronchiectasis.[34,35] Helical scanning (3-mm collimation) can improve CT detection of bronchiectasis compared to conventional HRCT (1.5 × 10 mm).[36] Finally, multidetector CT (MDCT; 1-mm slices) has been shown to be superior to HRCT (1 × 10 mm) in demonstrating the presence and extent of bronchiectasis.[37,38]

The only problem with the newer helical and MDCT scans is the increase in radiation dose to the patient.[36,39] In one study, with a tube current setting of 70 mA, MDCT provided acceptable quality images for the evaluation of bronchiectasis, but the radiation dose was five times higher with MDCT (10.54 mGy) versus conventional HRCT (2.17 mGy; at settings of 120 kVp, 170 mA, 1-mm collimation, and 10-mm intervals).[39]

HRCT Findings in ABPA

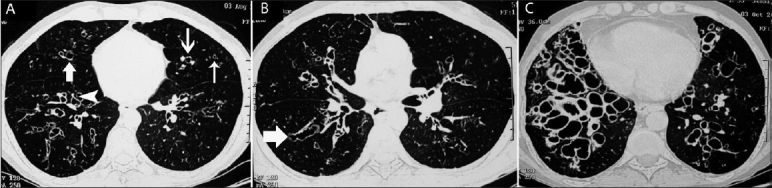

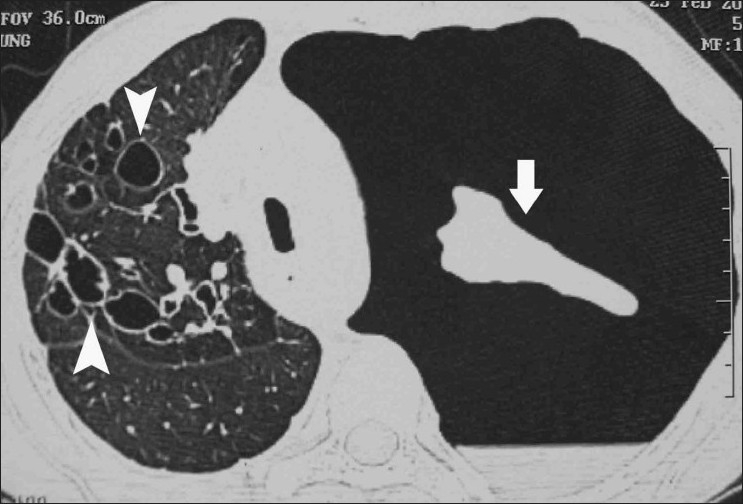

HRCT findings encountered in ABPA are shown in Table 5. Bronchiectasis is the most common finding,[40] On HRCT of the chest, a bronchus is considered to be dilated if the broncho-arterial ratio (internal diameter of the bronchus divided by the external diameter of its accompanying artery) is > 1.[41] Based on the appearance of the dilated bronchi, bronchiectasis is further classified into: (a) cylindrical bronchiectasis (the mildest form of which appears as tram-track or signet-ring depending on the orientation of bronchi relative to the scan plane); (b) varicose bronchiectasis (suggested by irregular bronchial walls with a beaded appearance); and (c) cystic bronchiectasis (which appears as a cluster of air-filled cysts) [Figure 10].[42]

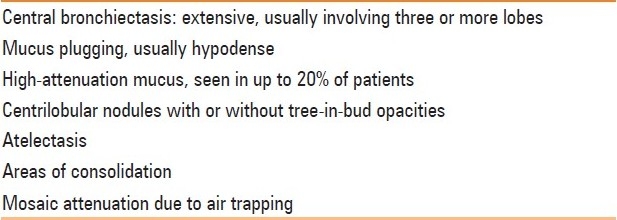

Table 5.

HRCT chest findings in ABPA

Figure 10 (A-C).

Axial HRCTs (lung window) show the various types of bronchiectasis in three different patients with ABPA: cylindrical bronchiectatic cavities (thin arrow) of various sizes with the characteristic signet-ring appearance (thick arrow) (A), varicose bronchiectasis (arrows in B), and cystic bronchiectasis

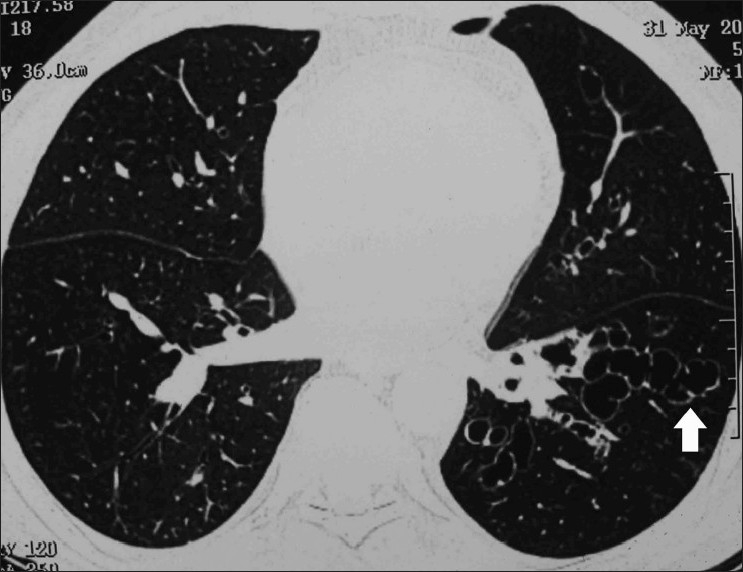

Central bronchiectasis (CB) is believed to be a characteristic finding in ABPA although there are no uniform criteria for the diagnosis of CB. Depending on the proximity of the dilated bronchi from the hilum at a point midway between the hilum and the chest wall, bronchiectasis is arbitrarily defined as central if confined to the medial two-thirds or the medial half of the lung [Figure 11].[43] Bronchiectasis can however extend to the periphery as well [Figure 12], and peripheral bronchiectasis has been described in 26%–39% of the lobes involved by bronchiectasis.[44,45] The bronchiectasis in ABPA usually involves the upper lobes although, rarely, there may be involvement of the lower zones without involvement of the upper lobes [Figure 13].

Figure 11.

Axial HRCT (lung window) shows the classic presentation of central bronchiectasis (arrow), with sparing of the periphery

Figure 12.

Axial HRCT (lung window) shows bronchiectasis (arrow) extending till the periphery

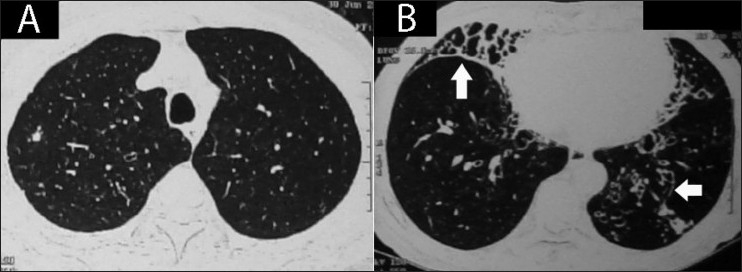

Figure 13(A, B).

Axial HRCT (lung window) through the upper lobes (A) and lower lobes (B) demonstrates predominant lower zone involvement by bronchiectasis (arrows) in a proven case of ABPA

Atelectasis and mucoid impaction: Atelectasis is usually subsegmental or segmental, occasionally lobar, and rarely can involve an entire lung [Figure 14]. Mucoid impaction is a common finding and is described as filling of the airways by mucoid secretions. The bronchial mucus plugging in ABPA is generally hypodense, but may also have high CT attenuation values [Figure 15].[45] High-attenuation mucus (HAM) is said to be present if the mucus plug is visually denser than the paraspinal skeletal muscle. Goyal et al. was the first to describe HAM in ABPA.[46] Although this radiological diagnosis was missed for long periods before[47] and probably even after the description of this finding,[48,49] numerous reports have since described the finding of HAM in ABPA.[50–55] Currently, the presence of HAM is considered pathognomonic of ABPA.[40] The constituents of HAM are not entirely clear. The reason for the hyperattenuating mucus is probably similar to that in patients with allergic fungal sinusitis,[56,57] and is currently attributed to the presence of calcium salts and metals (the ions of iron and manganese)[58] or desiccated mucus.[59]

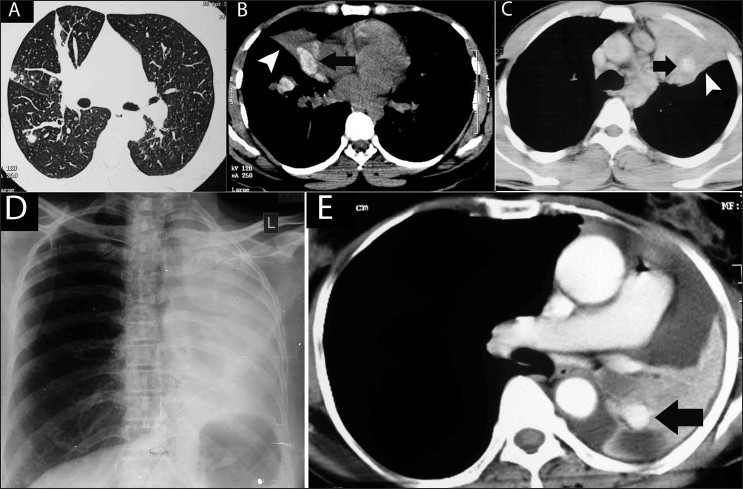

Figure 14 (A-E).

Atelectasis in ABPA in four different patients. Axial HRCT (lung window) (A) shows subsegmental atelectasis. Axial noncontrast CT scan (soft tissue window) (B) shows hyperattenuated mucus (arrow) with segmental collapse (arrowhead). Axial contrast enhanced CT scan (soft tissue window) (C) shows high attenuation mucus (arrow) within a collapsed left upper lobe and lingula (arrowhead). Chest radiograph (D) shows left lung collapse which is due to hyperdense mucus (arrow) within the collapsed lung, seen on this axial contrast-enhanced CT scan (E)

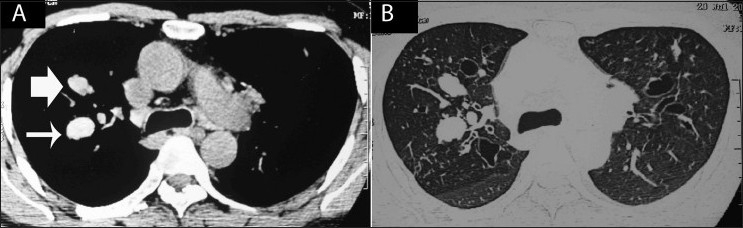

Figure 15 (A, B).

Axial HRCTs with soft tissue (A) and lung (B) windows show mucoid impaction with both hypo- (bold arrow) and hyper-dense (thin arrow) characteristics

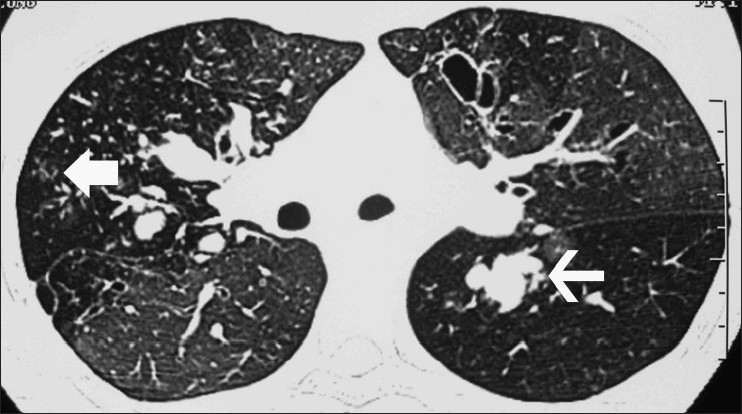

Other findings: In ABPA, centrilobular nodules are often seen as branching opacities, the so-called “tree-in-bud” pattern [Figure 16]. The finding of centrilobular nodules is more common in CB associated with ABPA than in CB associated with asthma.[60] Mosaic pattern presents on HRCT as patchy areas of differential attenuation within the lung. In patients with ABPA, the mosaic pattern is due to the concomitant small airways disease [Figure 16].

Figure 16.

Axial HRCT (lung window) shows a mosaic pattern. There is central bronchiectasis with mucoid impaction in many of the bronchiectatic cavities (thin arrow). Also seen are centrilobular nodules in a tree-in-bud pattern (bold arrow)

Pleural involvement in ABPA has been reported in the form of pleural effusion.[61–64] However, the most common pleural finding encountered in our patients was secondary spontaneous pneumothorax [Figure 17].[65,66]

Figure 17.

Axial HRCT (lung window) in a patient of ABPA who presented with a left-sided spontaneous pneumothorax (arrow). Extensive central and peripheral bronchiectasis is seen involving the right lung (arrowheads)

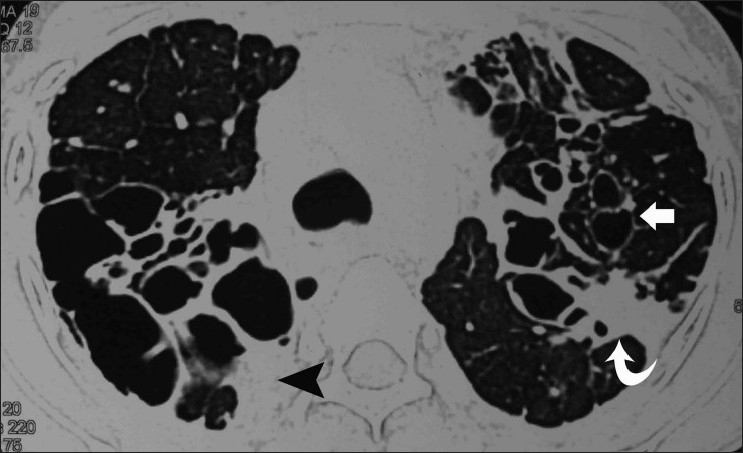

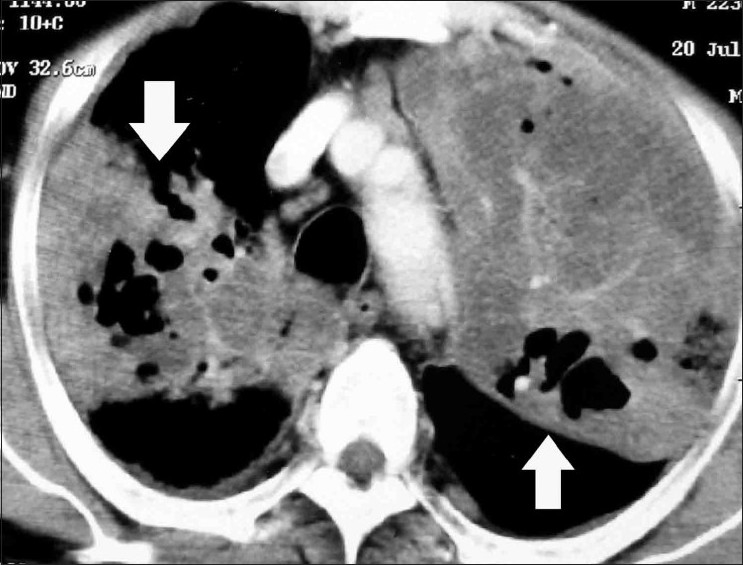

If ABPA is left untreated, there is progression of the disease, with development of extensive bronchiectasis and pulmonary fibrosis [Figure 18]. Eventually, type 2 respiratory failure, cor pulmonale, and right heart failure develop in end-stage fibrotic ABPA, with extensive bronchiectasis and fibrosis on HRCT of the chest.[67] Pulmonary hypertension can occasionally be the presenting manifestation of ABPA.[68] Other radiologic findings (ORF) described in ABPA include pulmonary fibrosis, blebs, bullae, parenchymal scarring, emphysematous change, multiple cysts, fibrocavitary lesions, and pleural thickening.[45,69,70] The presence of aspergilloma in dilated bronchiectatic cavities has also been documented.[71–73] Rarely, invasive aspergillosis can complicate the course of ABPA due to lowering of immunity, either because of chronic steroid therapy or due to occurrence of other immune suppressive illnesses.[74] The radiological picture is usually characterized by diffuse consolidation [Figure 19].

Figure 18.

Axial HRCT (lung window) shows extensive bronchiectatic cavities (arrows), with pleural (arrowhead) and pulmonary fibrosis (curved arrow)

Figure 19.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan in a patient with allergic aspergillosis who developed invasive aspergillosis. There are multiple large areas of consolidation (arrows), with areas of breakdown within these masses

ABPA with allergic Aspergillus sinusitis (AAS): Mucoid impaction akin to that seen in ABPA occurs in the paranasal sinuses of patients with AAS, which can be considered as the upper airway analogue of ABPA. The contemporaneous occurrence of both AAS and ABPA represents an extension of the allergic response to the presence of fungi within the sinus cavity.[75,76]

Clinical Significance of HRCT Findings

ABPA has been classified by Patterson et al. on the basis of HRCT chest findings as ABPA-CB and ABPA-S, depending on the presence or absence of bronchiectasis.[11] It was hypothesized by Greenberger et al. that ABPA-S is the earliest stage of ABPA, with less severe immunologic findings than in ABPA-CB.[77] However, in their study, only the A. fumigatus–specific IgG levels and precipitins were higher in patients with ABPA-CB; the other immunologic parameters (total IgE and A. fumigatus–specific IgE values) were similar in the two groups.[77] Kumar et al. subsequently divided ABPA into three groups, namely, ABPA-S, ABPA-CB, and ABPA-CB-ORF.[69] However, this study consisted of only 18 patients (6 in each group), and the HRCT manifestations in ABPA-CB-ORF included pulmonary fibrosis, blebs, bullae, pneumothorax, parenchymal scarring, emphysematous change, multiple cysts, fibrocavitary lesions, and pleural thickening – all findings representing end-stage fibrotic, probably immunologically quiescent, disease.

We have published the largest study to date on ABPA where we not only assessed the immunological parameters in both groups according to the earlier classifications but also suggested a new classification scheme based on HAM.[70] We believe that ABPA should be classified as ABPA-S, ABPA-CB, and ABPA-CB-HAM. In a study involving 234 patients with ABPA, we found that the classification scheme of Patterson and Greenberger et al.[11,77] showed immunological severity in some parameters (eosinophil count and A. fumigatus-specific IgE levels) but not in others (total IgE levels). On excluding patients with HAM, the immunological severity was restricted only to eosinophil counts. Interestingly, in the classification of Kumar et al,[69] the immunological markers were most severe in the ABPA-CB group and not in ABPA-CB-ORF, suggesting that ORF does not relate with immunological severity and probably represents the burnt-out phase of the disease.[70] The classification scheme based on HAM was the most consistent, with progressive increase in immunological severity from ABPA-S (mild) through ABPA-CB (moderate) to ABPA-CB-HAM (severe). Moreover, the presence of HAM at diagnosis not only represents immunologically severe disease but also identifies the patient at risk for recurrent relapses. In a multivariate analysis, both CB and HAM were independent predictors of frequent relapses of ABPA (OR: 3.41, 95% CI: 1.45 to 8.01 and OR: 3.61, 95% CI: 1.23 to 10.61, respectively).[70]

Utility of CT Scan in Diagnosis of ABPA

CT scan has been proposed as a diagnostic tool in the workup of asthmatic patients with minimal diagnostic criteria (asthma, Aspergillus skin test positivity, and CB) for the diagnosis of ABPA.[78] However, patients with asthma but without ABPA can also develop bronchiectasis.[79,80] In asthmatic patients, the presence of bronchiectasis affecting three or more lobes, with centrilobular nodules and mucoid impaction on HRCT, suggests ABPA.[60] However, a recent paper noted all these findings in Aspergillus-sensitized asthma without ABPA.[81] Hence, HRCT cannot be used in the initial workup of ABPA because of its poor positive predictive value.[82] Although HRCT findings in ABPA have been well described, there has been no uniformity in the reporting of various findings.[44,45,48,60,79,83–87] Moreover, there is no consistent criterion for defining CB, with some authors using the medial half[43,45,88] and others using the medial two-thirds as the distance from the hilum to the chest wall for the diagnosis.[44,48,79,85,86] The significance of CB as a specific diagnostic marker for ABPA is also controversial as it has been shown that almost 40% of involved lobes have bronchiectasis extending to the periphery.[44,45,87] HRCT of the chest by itself has a poor specificity in differentiating between the various etiologies of bronchiectasis.[89] While there is a good inter-observer agreement for the presence or absence of bronchiectasis in each lobe, the agreement between observers for the correct diagnosis is only moderate.[90] Reiff et al. reported that, by itself, the presence of CB had a sensitivity of only 37% for the diagnosis of ABPA.[88]

Although present in only about 20% of cases of ABPA,[70] HAM remains an important radiological sign for differentiating ABPA from asthma or other causes of bronchiectasis. The presence of HAM in patients with bronchiectasis confirms ABPA as the cause of the underlying bronchiectasis. The diagnosis of ABPA in CF is difficult as ABPA shares many clinical features with CF-lung disease without ABPA. Wheezing, fleeting pulmonary infiltrates, bronchiectasis, and mucus plugging are common manifestations of CF-pulmonary disease with or without ABPA.[91] Here, the diagnosis of HAM has important implications as its presence suggests that the lung disease is due to ABPA rather than CF per se.[55]

Conclusions

In summary, ABPA can present with diverse radiologic manifestations. Patients with ABPA can present with central as well as peripheral bronchiectasis. The sensitivity of CB as a predictor of ABPA is poor. HAM is a characteristic CT finding in ABPA and should be actively sought as its presence confirms the diagnosis of ABPA in patients with bronchiectasis. ABPA should be classified based on the presence or absence of HAM as ABPA-S, ABPA-CB, and ABPA-CB-HAM. The clinical significance of HRCT findings lies in the fact that the presence of CB or HAM at diagnosis predicts the risk for frequent relapses.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Agarwal R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: lessons learnt from genetics. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2011;53:137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal R, Chakrabarti A. Clinical Manifestations and Natural History of Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis. In: Pasqualotto AC, editor. Aspergillosis: From Diagnosis to Prevention. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 707–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal R, Chakrabarti A. Epidemiology of Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis. In: Pasqualotto AC, editor. Aspergillosis: From Diagnosis to Prevention. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 671–88. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agarwal R. Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis. In: Jindal SK, Shankar PS, Raoof S, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Agarwal R, editors. Textbook of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Publications; 2010. pp. 947–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal R. Severe Asthma with Fungal Sensitization. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:403–13. doi: 10.1007/s11882-011-0217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2009;135:805–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal R, Hazarika B, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Chakrabarti A, Jindal SK. Aspergillus hypersensitivity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: COPD as a risk factor for ABPA? Med Mycol. 2010;48:988–94. doi: 10.3109/13693781003743148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson R, Greenberger PA, Radin RC, Roberts M. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: staging as an aid to management. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:286–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-3-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinson KF, Moon AJ, Plummer NS. Broncho-pulmonary aspergillosis; a review and a report of eight new cases. Thorax. 1952;7:317–33. doi: 10.1136/thx.7.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal R, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Saxena AK, Saikia B, Chakrabarti A, et al. Clinical significance of decline in serum IgE Levels in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Respir Med. 2010;104:204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patterson R, Greenberger PA, Halwig JM, Liotta JL, Roberts M. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.Natural history and classification of early disease by serologic and roentgenographic studies. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:916–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.146.5.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy DS, Simon G, Hargreave FE. The radiological appearances in allergic broncho-pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Radiol. 1970;21:366–75. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(70)80070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malo JL, Pepys J, Simon G. Studies in chronic allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. 2. Radiological findings. Thorax. 1977;32:262–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.32.3.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menon MP, Das AK. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (radiological aspects) Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 1977;19:157–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mintzer RA, Rogers LF, Kruglik GD, Rosenberg M, Neiman HL, Patterson R. The spectrum of radiologic findings in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Radiology. 1978;127:301–7. doi: 10.1148/127.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendelson EB, Fisher MR, Mintzer RA, Halwig JM, Greenberger PA. Roentgenographic and clinical staging of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 1985;87:334–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.87.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal R, Srinivas R, Agarwal AN, Saxena AK. Pulmonary masses in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: mechanistic explanations. Respir Care. 2008;53:1744–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann H. Hilar adenopathy in aspergillosis. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:346. author reply 347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van den Berg PM, Hoogsteden HC. Hilar adenopathy in aspergillosis. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:346–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal R, Reddy C, Gupta D. An unusual cause of hilar lymphadenopathy. Lung India. 2006;23:90–2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah A, Kala J, Sahay S. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with hilar adenopathy in a 42-month-old boy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:747–8. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hantsch CE, Tanus T. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with adenopathy. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:546–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-7-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah A, Agarwal AK, Chugh IM. Hilar adenopathy in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;82:504–6. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62729-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Bal A, Das A. Case report: A rare cause of miliary nodules -- allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:e151–4. doi: 10.1259/bjr/20940804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Currie DC, Cooke JC, Morgan AD, Kerr IH, Delany D, Strickland B, et al. Interpretation of bronchograms and chest radiographs in patients with chronic sputum production. Thorax. 1987;42:278–84. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.4.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scadding JG. The bronchi in allergic aspergillosis. Scand J Respir Dis. 1967;48:372–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logan PM, Muller NL. High-resolution computed tomography and pathologic findings in pulmonary aspergillosis: a pictorial essay. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1996;47:444–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooke JC, Currie DC, Morgan AD, Kerr IH, Delany D, Strickland B, et al. Role of computed tomography in diagnosis of bronchiectasis. Thorax. 1987;42:272–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.4.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munro NC, Cooke JC, Currie DC, Strickland B, Cole PJ. Comparison of thin section computed tomography with bronchography for identifying bronchiectatic segments in patients with chronic sputum production. Thorax. 1990;45:135–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joharjy IA, Bashi SA, Adbullah AK. Value of medium-thickness CT in the diagnosis of bronchiectasis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:1133–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.6.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips MS, Williams MP, Flower CD. How useful is computed tomography in the diagnosis and assessment of bronchiectasis? Clin Radiol. 1986;37:321–5. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(86)80261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller NL, Bergin CJ, Ostrow DN, Nichols DM. Role of computed tomography in the recognition of bronchiectasis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:971–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.143.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mootoosamy IM, Reznek RH, Osman J, Rees RS, Green M. Assessment of bronchiectasis by computed tomography. Thorax. 1985;40:920–4. doi: 10.1136/thx.40.12.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young K, Aspestrand F, Kolbenstvedt A. High resolution CT and bronchography in the assessment of bronchiectasis. Acta Radiol. 1991;32:439–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grenier P, Maurice F, Musset D, Menu Y, Nahum H. Bronchiectasis: assessment by thin-section CT. Radiology. 1986;161:95–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.161.1.3763889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucidarme O, Grenier P, Coche E, Lenoir S, Aubert B, Beigelman C. Bronchiectasis: comparative assessment with thin-section CT and helical CT. Radiology. 1996;200:673–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.3.8756913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dodd JD, Souza CA, Muller NL. Conventional high-resolution CT versus helical high-resolution MDCT in the detection of bronchiectasis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:414–20. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill LE, Ritchie G, Wightman AJ, Hill AT, Murchison JT. Comparison between conventional interrupted high-resolution CT and volume multidetector CT acquisition in the assessment of bronchiectasis. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:67–70. doi: 10.1259/bjr/96908158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi CA, Lee KS, Kim TS, Han D, Sung YM, Kim S. Multidetector CT of bronchiectasis: effect of radiation dose on image quality. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:501–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.2.1810501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webb WR, Muller NL, Naidich DP. 4th ed. Philadelphia: LWW; 2009. Airway Diseases. High-Resolution CT of the Lung; pp. 492–554. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Webb WR, Muller NL, Naidich DP. 4th ed. Philadelphia: LWW; 2009. High-Resolution Computed Tomography Findings of Lung Disease. High-Resolution CT of the Lung; pp. 65–176. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naidich DP, McCauley DI, Khouri NF, Stitik FP, Siegelman SS. Computed tomography of bronchiectasis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1982;6:437–44. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansell DM, Strickland B. High-resolution computed tomography in pulmonary cystic fibrosis. Br J Radiol. 1989;62:1–5. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-62-733-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panchal N, Bhagat R, Pant C, Shah A. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: the spectrum of computed tomography appearances. Respir Med. 1997;91:213–9. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(97)90041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agarwal R, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Behera D, Jindal SK. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: lessons from 126 patients attending a chest clinic in north India. Chest. 2006;130:442–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goyal R, White CS, Templeton PA, Britt EJ, Rubin LJ. High attenuation mucous plugs in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: CT appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16:649–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fraser RG, Pare JAP, Pare PD, Fraser RS, Genereux GP. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1989. Mycotic and Actinomycotic pleuropulmonary infections. Diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest; pp. 940–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sandhu M, Mukhopadhyay S, Sharma SK. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: a comparative evaluation of computed tomography with plain chest radiography. Australas Radiol. 1994;38:288–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1994.tb00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aquino SL, Kee ST, Warnock ML, Gamsu G. Pulmonary aspergillosis: imaging findings with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:811–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.4.8092014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Logan PM, Muller NL. High-attenuation mucous plugging in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1996;47:374–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karunaratne N, Baraket M, Lim S, Ridley L. Case quiz. Thoracic CT illustrating hyperdense bronchial mucous plugging: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Australas Radiol. 2003;47:336–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.2003.01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Molinari M, Ruiu A, Biondi M, Zompatori M. Hyperdense mucoid impaction in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: CT appearance. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2004;61:62–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D. High-attenuation mucus in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: another cause of diffuse high-attenuation pulmonary abnormality. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:904. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agarwal R, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Saxena AK, Chakrabarti A, Jindal SK. Clinical significance of hyperattenuating mucoid impaction in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: an analysis of 155 patients. Chest. 2007;132:1183–90. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morozov A, Applegate KE, Brown S, Howenstine M. High-attenuation mucus plugs on MDCT in a child with cystic fibrosis: potential cause and differential diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:592–5. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manning SC, Merkel M, Kriesel K, Vuitch F, Marple B. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:170–6. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199702000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mukherji SK, Figueroa RE, Ginsberg LE, Zeifer BA, Marple BF, Alley JG, et al. Allergic fungal sinusitis: CT findings. Radiology. 1998;207:417–22. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.2.9577490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kopp W, Fotter R, Steiner H, Beaufort F, Stammberger H. Aspergillosis of the paranasal sinuses. Radiology. 1985;156:715–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.3.4023231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dillon WP, Som PM, Fullerton GD. Hypointense MR signal in chronically inspissated sinonasal secretions. Radiology. 1990;174:73–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.1.2294574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ward S, Heyneman L, Lee MJ, Leung AN, Hansell DM, Muller NL. Accuracy of CT in the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in asthmatic patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:937–42. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.4.10511153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murphy D, Lane DJ. Pleural effusion in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: two case reports. Br J Dis Chest. 1981;75:91–5. doi: 10.1016/s0007-0971(81)80013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Connor TM, O’Donnell A, Hurley M, Bredin CP. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: a rare cause of pleural effusion. Respirology. 2001;6:361–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2001.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ogasawara T, Iesato K, Okabe H, Murata K, Kominami S, Tomita K, et al. [A case of pleural effusion associated with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis during a relapse of the disease] Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;41:905–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirschner AN, Kuhlmann E, Kuzniar TJ. Eosinophilic Pleural Effusion Complicating Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis. Respiration. 2011;82:478–81. doi: 10.1159/000323617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D. Efficacy and safety of iodopovidone pleurodesis through tube thoracostomy. Respirology. 2006;11:105–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agarwal R, Paul AS, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Jindal SK. Efficacy of cosmetic talc vs.iodopovidone for chemical pleurodesis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Respirology. 2011;16:1064–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.01999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee TM, Greenberger PA, Patterson R, Roberts M, Liotta JL. Stage V (fibrotic) allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. A review of 17 cases followed from diagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:319–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agarwal R, Singh N, Gupta D. Pulmonary hypertension as a presenting manifestation of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2009;51:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumar R. Mild, moderate, and severe forms of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical and serologic evaluation. Chest. 2003;124:890–2. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agarwal R, Khan A, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Saxena AK, Chakrabarti A. An alternate method of classifying allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis based on high-attenuation mucus. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Safirstein BH. Aspergilloma consequent to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973;108:940–3. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.108.4.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shah A, Khan ZU, Chaturvedi S, Ramchandran S, Randhawa HS, Jaggi OP. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with coexistent aspergilloma: a long-term followup. J Asthma. 1989;26:109–15. doi: 10.3109/02770908909073239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Montani D, Zendah I, Achouh L, Dorfmuller P, Mercier O, Garcia G, et al. Association of pulmonary aspergilloma and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:349–51. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00004810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gupta K, Das A, Joshi K, Singh N, Aggarwal R, Prakash M. Aspergillus endocarditis in a known case of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: an autopsy report. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2010;19:e137–9. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shah A, Panchal N, Agarwal AK. Concomitant allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and allergic Aspergillus sinusitis: a review of an uncommon association*. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1896–905. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saravanan K, Panda NK, Chakrabarti A, Das A, Bapuraj RJ. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: an attempt to resolve the diagnostic dilemma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:173–8. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Greenberger PA, Miller TP, Roberts M, Smith LL. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with and without evidence of bronchiectasis. Ann Allergy. 1993;70:333–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eaton T, Garrett J, Milne D, Frankel A, Wells AU. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in the asthma clinic.A prospective evaluation of CT in the diagnostic algorithm. Chest. 2000;118:66–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Neeld DA, Goodman LR, Gurney JW, Greenberger PA, Fink JN. Computerized tomography in the evaluation of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:1200–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.5.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paganin F, Trussard V, Seneterre E, Chanez P, Giron J, Godard P, et al. Chest radiography and high resolution computed tomography of the lungs in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1084–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Menzies D, Holmes L, McCumesky G, Prys-Picard C, Niven R. Aspergillus sensitization is associated with airflow limitation and bronchiectasis in severe asthma. Allergy. 2011;66:679–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Agarwal R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: Lessons for the busy radiologist. World J Radiol. 2011;3:178–81. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v3.i7.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Currie DC, Goldman JM, Cole PJ, Strickland B. Comparison of narrow section computed tomography and plain chest radiography in chronic allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Radiol. 1987;38:593–6. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(87)80333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shah A, Pant CS, Bhagat R, Panchal N. CT in childhood allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:227–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02012505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Angus RM, Davies ML, Cowan MD, McSharry C, Thomson NC. Computed tomographic scanning of the lung in patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and in asthmatic patients with a positive skin test to Aspergillus fumigatus. Thorax. 1994;49:586–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.6.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Panchal N, Pant C, Bhagat R, Shah A. Central bronchiectasis in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: comparative evaluation of computed tomography of the thorax with bronchography. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:1290–3. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07071290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mitchell TA, Hamilos DL, Lynch DA, Newell JD. Distribution and severity of bronchiectasis in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) J Asthma. 2000;37:65–72. doi: 10.3109/02770900009055429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reiff DB, Wells AU, Carr DH, Cole PJ, Hansell DM. CT findings in bronchiectasis: limited value in distinguishing between idiopathic and specific types. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:261–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.2.7618537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee PH, Carr DH, Rubens MB, Cole P, Hansell DM. Accuracy of CT in predicting the cause of bronchiectasis. Clin Radiol. 1995;50:839–41. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)83104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cartier Y, Kavanagh PV, Johkoh T, Mason AC, Muller NL. Bronchiectasis: accuracy of high-resolution CT in the differentiation of specific diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:47–52. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.1.10397098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Agarwal R. Controversies in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. (56-63).Int J Respir Care. 2010;6:53–4. [Google Scholar]