Abstract

Hemangiomas are hamartomatous proliferation of vessels. Intraosseous hemangiomas of the facial bones are rare and most commonly involve the zygoma, maxilla, mandible, and the nasal bones. A “sunburst” pattern is a typical appearance on CT scan and MRI and therefore a biopsy is not always necessary. Surgery is usually performed in symptomatic cases. The authors describe five typical periorbital intraosseous hemangiomas with a brief review of literature.

Keywords: Cavernous hemangiomas, computed tomography, intraosseous, magnetic resonance, periorbital

Introduction

A hemangioma is a benign proliferation of endothelial-lined vascular channels.[1] Intraosseous hemangiomas (IH) occur in all age groups, being more commonly seen in the axial skeleton, especially the spine.[2] Facial IH are rare and usually periorbital, zygomatic, maxillary, or mandibular in location.[1] Skull and spine IH are usually asymptomatic and found only incidentally, whereas those involving the face are often symptomatic[2] and present with painless swelling or local pain/paresthesia, which is usually due to nerve compression.[3] Proptosis, diplopia, and visual loss are very uncommon.[4] We describe five cases of periorbital IH with relevant imaging findings and present a brief review of the literature.

Case Reports

Case 1

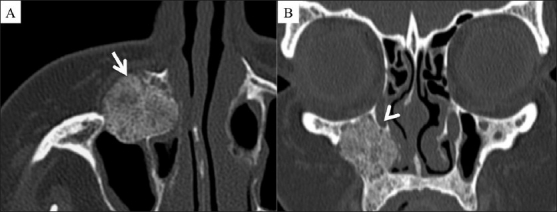

A 47-year-old female presented with a slow-growing, nontender, immobile right malar mass for 3 years and recent epiphora. Plain CT scan of the orbits demonstrated an expansile, well-defined osseous lesion in the right anterior maxilla, with narrowing of the lacrimal duct [Figures 1A and B]. Partial resection of this lesion restored the normal lacrimal drainage.

Figures 1 (A, B).

Axial (A) and coronal (B) CT scans of the facial bones show an intraosseous cavernous hemangioma in the anterior wall of the right maxillary sinus (arrow), causing narrowing of the lacrimal duct (arrowhead). Note the typical multiple spicules with a radiating appearance with no significant soft tissue component

Case 2

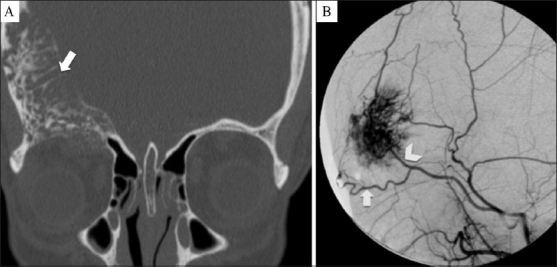

A 32-year-old female with a firm right orbital mass presented with proptosis and diplopia for 6 months. Angiography was carried out to exclude an arteriovenous malformation [Figures 2A and B]. Presurgical embolization with subtotal resection improved her symptoms.

Figures 2 (A, B).

Coronal CT scan (A) shows a large intraosseous mass with prominent vascular channels causing thickening of the frontal bone and right orbit roof (arrow). Digital subtraction angiography (B) shows the intense blush of the mass, fed by the supraorbital (arrow) and the superficial temporal (arrowhead) arteries

Case 3

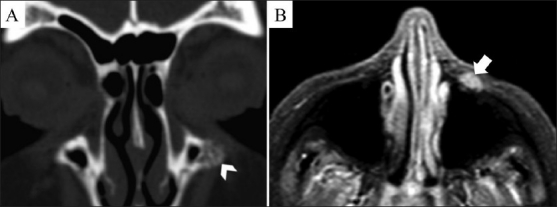

A 49-year-old female presented with chronic sinusitis. CT scan and MRI demonstrated a very small intraosseous lesion with a typical “sunburst” pattern in the anterior orbital floor, which remained stable for two years of follow-up [Figures 3A and B].

Figures 3 (A, B).

Coronal CT scan (A) and axial, contrast-enhanced, fat-suppressed T1W MRI (B) show a small periorbital intraosseous hemangioma in the anterior wall of the left maxillary sinus (arrowhead) with moderate enhancement (arrow)

Case 4

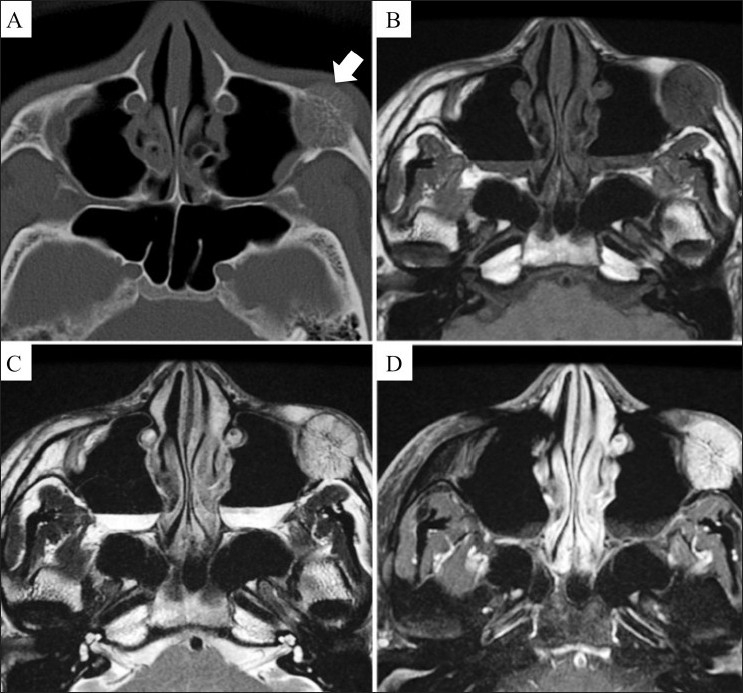

A 47-year-old male presented with facial asymmetry and left cheek deformity that had increased significantly over the past 6 months. CT scan of the facial bones showed an osseous lesion in the zygomatico-maxillary suture [Figure 4A]. MRI demonstrated a well-demarcated T1-hypointense and T2-hyperintense, enhancing lesion with a characteristic radiating pattern [Figure 4B–D]. Postsurgical recovery was uneventful.

Figures 4 (A-D).

Axial CT scan (A) shows the characteristic radiating appearance of an intraosseous cavernous hemangioma (arrow) arising in the left zygomatic-maxillary fissure. The mass shows low signal (arrow) on the axial T1W MRI image (B), high signal (arrow) on the axial T2W MRI image (C), and avid enhancement (arrow) on a contrast-enhanced T1W fat-saturated MRI image (D)

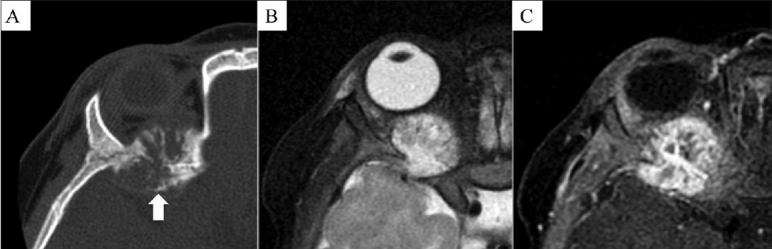

Case 5

A 19-month-old girl presented with proptosis since birth. CT scan showed a right orbital roof mass with prominent trabeculations [Figure 5]. On MRI the mass appeared hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI, with avid enhancement. Partial surgical resection was done, with significant improvement of the proptosis.

Figures 5 (A-C).

Axial CT scan (A) shows an intraosseous cavernous hemangioma (arrow) arising from the sphenoid process of the right orbit demonstrating vascular channels with the usual radiating distribution. Note the intrinsic high signal (arrow) on the axial T2W MRI image (B) and the usual enhancement (arrow) on an axial, contrast-enhanced, fat-suppressed T1W MRI image (C)

Discussion

Toynbee reported the first facial IH in 1845,[5] but the first case with pathological correlation was described by Rowbotham in 1942.[6] Less than 50 cases have been reported in the imaging and surgical literature.[7]

Hemangiomas were originally classified as vascular neoplasms, but are now considered as hamartomatous vascular proliferations.[1] According to the WHO classification there are five histological types of hemangiomas: cavernous, capillary, epithelioid, histiocytoid, and sclerosing.[8] According to Madge et al., the most common periorbital IH are the cavernous type (80%), followed by the capillary (17%) and mixed varieties (3%).[7]

IH are exceedingly uncommon in the facial bones and involve the frontal bone (38%), zygomatic bone (36%), sphenoid bone (20%), maxilla (18%), ethmoid (9%), and rarely, the lacrimal bone (2%). IH occur in all age groups, with a peak incidence during the fourth and fifth decades. They are more common in women, with a M:F ratio of 1:1.5.[2]

Facial IH are usually symptomatic. The majority of patients present with an enlarging orbital mass (60%), one third with periorbital pain, 29% with proptosis; less common symptons include blurred or reduced vision (16%), diplopia or ophthalmoplegia (13%), epiphora (11%), epistaxis (9%), nasal obstruction (7%), headache (7%), and red eye (4%). When vision is affected, the changes range from minor visual field defects to the absence of light perception.[9]

The typical radiographic appearance of IH was first described by Bucy and Capp in 1930[10] and by Wyke in 1949.[11] It appears as well-defined areas of circumscribed honeycombing and bone rarefaction, leading to a “bubbly” appearance. On cross-sectional imaging, IH are characterized by their classic trabecular pattern with radiating spicules, resulting in a “sunburst” appearance; there are no significant reactive bony changes.[9] CT scan is the modality of choice to assess IH as it provides excellent details of the cortical margins and the trabecular pattern. MRI is superior to CT scan for the evaluation of highly vascularized lesions and extraosseous soft tissue involvement.[12,13] The MRI appearances vary, depending on the size, the degree of yellow and red marrow composition, and the intralesional vascularity. These lesions typically have a mottled appearance on T1W and T2W images. Smaller lesions are hyperintense on T1W images, while the larger lesions appear hypointense. IH are predominantly hyperintense on T2W images and after gadolinium injection, demonstrate characteristic progressive focal and incomplete enhancement in the early phase, followed by a generalized delayed pattern of enhancement.[7,14]

Preoperative angiography, and at times embolization, help in demonstrating feeders from branches of the external carotid arteries and significantly minimize operative blood loss.[1] Technetium-labeled red blood cells scintigraphy is one of the modalities useful for demonstrating prominent vascular flow and blood pooling.[3]

The differential diagnosis includes exostoses, eosinophilic granuloma, fibrous dysplasia, dermoid cyst, multiple myeloma, and osteoid osteoma.[3]

Surgery is usually indicated for lesions that show a progressive increase in size and for cosmetic reasons. An important and fearsome complication is the possibility of profuse hemorrhage when they are treated surgically and hence the need for accurate preoperative diagnosis.[15] Alternative therapeutic modalities are embolization and radiotherapy. Percutanous or transarterial embolization can be performed with variable results but the benefits are often offset by the risks associated with these procedures.[3]

In conclusion, facial and periorbital IH are extremely rare hamartomatous vascular malformations. These lesions have characteristic imaging features that allow accurate diagnosis and thus help avoid unnecessary investigations and delays in management.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Moore SL, Chun JK, Mitre SA, Som PM. Intraosseous hemangioma of the zygoma: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1383–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenger DE, Wold LE. Benign vascular lesions of bone: Radiologic and pathologic features. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29:63–74. doi: 10.1007/s002560050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng NC, Lai DM, Hsie MH, Liao SL, Chen YB. Intraosseous hemangiomas of the facial bone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:2366–72. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000218818.16811.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuesta Gil M, Navarro-Vila C. Intraosseous hemangioma of the zygomatic bone.A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;21:287–91. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80739-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toynbee J. An account of two vascular tumours developed in the substance of bone. Lancet. 1845;2:676. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowbotham G. Haemangiomata arising in bones of the skull. Brit J Surg. 1942;30:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madge SN, Simon S, Abidin Z, Ghabrial R, Davis G, McNab A, et al. Primary orbital intraosseous hemangioma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:37–41. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318192a27e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler CP, Wold L. Haemangioma and related lesions. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. pp. 319–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slaba SG, Karam RH, Nehme JI, Nohra GK, Hachem KS, Salloum JW. Intraosseous orbitosphenoidal cavernous angioma.Case report. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:1034–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.6.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bucy P, Capp C. Primary haemangioma of bone with special reference to the roentgenological diagnosis. Am J Roentgenol. 1930;23:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyke B. Primary haemangioma of the skull: A rare cranial tumor.Review of the literature and report of a case, with special reference to the roentgenographic appearances. Am J Roentgenol. 1949;61:302–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeter TS, Hackney FL, Aufdemorte TB. Cavernous hemangioma of the zygoma: Report of cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:508–12. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90242-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warman S, Myssiorek D. Hemangioma of the zygomatic bone. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989;98:655–8. doi: 10.1177/000348948909800817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Har-El G, Levy R, Avidor I, Segal K, Sidi J. Haemangioma of the zygoma presenting as a tumour in the maxillary sinus. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14:161–4. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rios Dias GD, Velasco Cruz AA. Intraosseous hemangioma of the lateral orbital wall. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:27–30. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000105565.82438.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]