Abstract

The sickle cell (HbS) gene occurs at a variable frequency in the Middle Eastern Arab countries, with characteristic distribution patterns and representing an overall picture of blood genetic disorders in the region. The origin of the gene has been debated, but studies using β-globin gene haplotypes have ascertained that there were multiple origins for HbS. In some regions the HbS gene is common and exhibits polymorphism, while the reverse is true in others. A common causative factor for the high prevalence and maintenance of HbS and thalassaemia genes is malaria endemicity. The HbS gene also co-exists with other haemoglobin variants and thalassaemia genes and the resulting clinical state is referred to as sickle cell disease (SCD). In the Middle Eastern Arab countries, the clinical picture of SCD expresses two distinct forms, the benign and the severe forms, which are related to two distinct β-globin gene haplotypes. These are referred to as the Saudi-Indian and the Benin haplotypes, respectively. In a majority of the Middle Eastern Arab countries the HbS is linked to the Saudi-Indian haplotype, while in others it is linked to the Benin haplotype. This review outlines the frequency, distribution, clinical feature, management and prevention as well as gene interactions of the HbS genes with other haemoglobin disorders in the Middle Eastern Arab countries.

Keywords: Malaria endemicity, middle Eastern countries, sickle cell anaemia, sickle cell disease, The Arabs

The Middle Eastern Arab community features and genetic disorders

Of particular interest in the Middle East Arabs are a set of common factors that include the rapid increase in the population and rich historical, cultural, traditional and religious commonality. The large family size, high rate of consanguinity in conjunction with tribe/clan endogamy, make the Arabs unique from the point of view of genetic analysis.

Over the years, the Arabs in the Middle East have undergone a considerable transition as regards the health status of its people. Infectious diseases and nutritional disorders have decreased in prevalence as a result of the significant advances made in immunization, the discovery of antibiotics and the overall improvement in hygiene. Thus, these earlier causes of morbidity and mortality are now being exceeded by genetic diseases, which although relatively infrequent, constitute a significant cause of chronic health problems, morbidity and mortality and hence are a major burden on health care systems.

In the industrialized countries, community surveys show that approximately 3 per cent of all pregnancies result in the birth of a child with a significant genetic disease or birth defect which can cause mental retardation, other crippling conditions or early death1. Though data on genetic and congenital defects are not handy in the Arab communities, but considering the high rate of consanguinity and other relevant factors, it is predicted that these disorders are more frequent in this population. Genetic diseases due to their chronic nature impose heavy medical, financial and emotional burdens2. Therefore, the efforts to combat these problems are multifaceted and the effective control and prevention strategies gain a high priority beside care and rehabilitation of the affected in the community.

Haemoglobin disorders as genetic diseases

Normal haemoglobins are of different types in human and include Hb A, Hb A2 and Hb F. Each type of haemoglobin is a tetramer of two different globin chains, each having its own gene. The Hb A (2α2β) is almost 95-97 per cent, Hb A2(2α2δ) is 2.5-3.5 per cent and Hb F (2α2γ) is <1 per cent in adults. The α-globin gene cluster is located on the chromosome 16 and includes 5’-ζ-ψα-α2-α1-3’, while the non-α globin gene cluster which includes 5’-ε-Gγ-Aγ-ψβ-δ-β-3’ genes, is located on the chromosome 11. The expression of α1 and α2 globin genes located on chromosome 16pter-p13.3 and the β globin gene located on chromosome 11p15.5, provide α and β globin polypeptides, and the co-ordinated production of haem, the non-protein portion of Hb chains, results in the formation of HbA, in normal individuals3,4. An A to T transversion mutation at the sixth codon of the β globin gene produces HbS, with a substitution of glutamic acid by valine at the 6th amino acid position in the β globin polypeptide. Individuals homozygous to HbS gene have only HbS in place of Hb A, with concomitant production of Hb F and Hb A2. In double heterozygotes, the HbS co-exists with either other abnormal haemoglonis or with thalassaemias. These groups of disorders are together referred to as sickle cell disease (SCD). Majority of the haemoglobin variants other than HbS, HbC, HbE and HbD are rare, and therefore, rarely give rise to homozygote states. However, thalassaemias, on their own occur more frequently giving rise to homozygous disease conditions5.

Pattern of inheritance of haemoglobin disorders

The abnormal haemoglobins and the thalassaemias are inherited as autosomal recessive (AR) disorders, where carrier parents transmit the abnormal genes to the offspring. If both parents are heterozygotes for HbS, there is a 25 per cent chance of having a homozygous HbSS (Sickle cell anaemia, SCA) child. If one parent is a carrier for HbS and the other is carrier for one of the abnormal HbS or thalassaemias, it results in a double heterozygote state. Heterozygotes are generally asymptomatic carriers (traits), while the SCD is expressed in the homozygotes and the double heterozygotes for two abnormal haemoglobin genes or HbS and the thalassaemias.

Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease

The Hb S is soluble in the oxygenated state, as that encountered in the lungs, but once the haemogloin delivers the oxygen to the tissues, the HbS in the deoxygenated form undergoes a major conformational change, which leads to the formation of long fibrous aggregates (polymers) due to hydrophobic interactions between the valines in the adjacent HbS molecules. These polymers in the erythrocyte, distort its shape from normal spherical biconcave disc to the characteristic sickle shape, leading to erythrocyte rigidity and vaso-occlusion and sickled red cells are formed in the tissues6. The haemoglobin olymerization is central mechanism to the pathophysiology of SCD. Constant sickling and desickling in the tissues and the lungs respectively, increase the fragility of the red cells leading to haemolysis and hence chronic anaemia. Vaso-occlusion results from blockage of the blood vessels by the rigid sickled red cells, leading to the development of painful crises, hand-foot syndrome, inflammation, cerebrovascular disease and cognitive impairment. Recurrent episodes of vaso-occlusion and inflammation lead to vasculopathy which further results in progressive damage to most organs, including the brain, kidneys, lungs, bones, and cardiovascular system obstructs microcirculation, and causes tissue infarction4,7. These frequently result in hand-foot syndrome in children, fatigue, paleness, and shortness of breath, pain that occurs unpredictably in any body organ or joint, eye problems, yellowing of skin and eyes, delayed growth and puberty in children. In addition, infections, stroke, and acute chest pain are some of the major complications. These complications start in early life, but become more apparent with increasing age. Several factors such as infections, dehydration, fever, cold weather and stress precipitate the complications. Most of the treatments are directed towards prevention of or decreasing sickling and hence reduction in the vasculopathy and clinical complications of SCD4,6–8.

Origin of sickle cell gene

Studies on haplotypes generated using restriction endonuclease, associated with HbS have confirmed that the HbS mutation occurred as several independent events in Central Africa, Central West Africa, African West coast, Arabian Peninsula and India. In Africa the HbS gene is associated with at least three haplotypes representing independent mutations. These are the Benin haplotype, the Senegal haplotype in the Central African Republic or the Bantu haplotype found in the Central West Africa, the African West coast and the Central Africa (Bantu speaking Africa), respectively. A fourth haplotype, the Saudi-Asian haplotype, is found in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia and central India. Though the origin of HbS was mainly in Africa and Asia, as a result of population movement it spread to different areas of the World and became established in areas which were endemic to malaria. This is due to the natural resistance against development of malaria, in the HbS carriers. At present, HbS has been reported from several countries of the world and the frequency is high in areas with past or present history of malaria endemicity9,10.

Haemoglobin disorders – occurrence and distribution

The disorders resulting from inheritance of HbS gene are among the most frequently encountered group of disorders in several populations of the World, in particular among the sub-Saharan Africa; Middle Eastern populations; other Mediterranean countries such as Northern Greece, Sicily and Southern Italy; Spanish-speaking regions (South America, Cuba, Central America), Southern Turkey and much of Central India. Studies have confirmed that the HbS mutation is a relatively recent occurrence, which has occurred independently in several different populations and the presence of falciparum malaria has served as a selective factor in increasing its prevalence11. This is the consequence of the inborn resistance to the development of malaria, which arises in the HbS heterozygotes (carriers), who are less likely to die from malaria and so more likely to survive and pass on their genes, thus playing an important role in maintaining HbS gene frequency. Over the generations, the HbS gene has reached high frequencies in regions with past or present history of malaria endemicity. However, population migration has played a major role in distributing HbS gene even to non malaria endemic regions. Also several hundred mutations affect the globin genes, but only a few occur at a polymorphic level, and majority of the abnormal haemoglobins (Hbs) occur as rare variants, confined to specific ethnic groups or families12.

Epidemiology of sickle cell gene

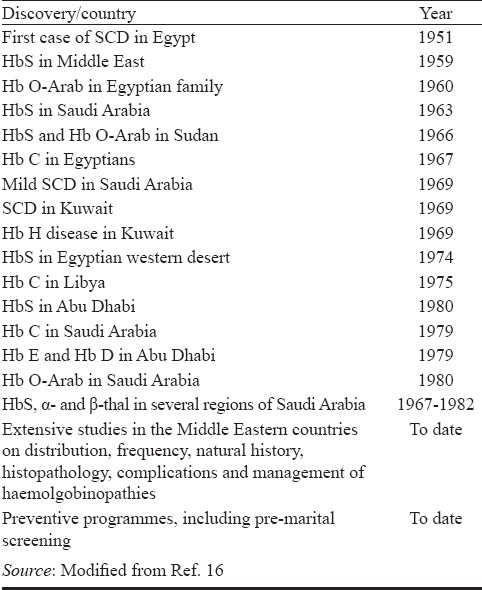

The SCD is most common among people from Africa, India, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. In the Middle Eastern countries, the first documentation of abnormal Hbs (HbS) and thalassaemias came from Egypt13,14. Lehmann reported the presence of HbS in Eastern Saudi Arabia15. Extensive studies on different haemoglobin disorders have been reported from almost all the countries of the Middle East, though at a considerably variable frequency. Table I presents brief historical aspects related to identification of abnormal haemogloins in the Middle Eastern population, and different abnormal variants that have been identified are listed in Table II. HbS is the major variant identified in all areas. Table III presents the range of HbS gene frequencies reported from the different Middle Eastern countries16. Each country has characteristic distribution and clinical presentation of SCD.

Table 1.

Haemoglobinopathies in the Middle East Arab countries – Historical aspects

Table II.

Abnormal haemoglobins identified in the Middle Eastern Arab countries

Table III.

Gene frequency and common disease pattern of sickle cell haemoglobin (HbS) in the Middle Eastern Arab countries

Frequency and distribution of sickle cell gene among Arabs

Geographically, Middle Eastern Arabs can be looked at as follows: (i) the Arabian peninsula occupying the South West of Asia includes the Yemen, Saudi Arabia and other members of Gulf Co-operation Council, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates and Oman; (ii) the Northern region of Arabian Peninsula that occupies the North West of Asia and includes Palestine, Jordon, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq; and (iii) the Arab countries of North Africa, that include Egypt, Libya, Tunis, Algeria and Morocco.

(i) The Middle Eastern Arab countries of Western Asia

Yemen: In the study of White and coworkers17 the frequency of SCD in Yemen was reported as 0.95 per cent. Disease course and severity were similar to that in Africans and American blacks and from western Saudi Arabia18. In the individuals with SCA, the prevalence of Xmn I polymorphic sites was reported to be similar to the prevalence reported in the south-western region of Saudi Arabia19 and α-gene deletion occurred at a higher prevalence in patients with Yemeni SCD patients20.

Saudi Arabia: Sickle cell gene was first recognized in Saudi Arabia in 1963 by Lehmann and co-workers in the eastern province of the country21. Gelpi reported the presence of HbS gene in the oasis population of Al-Qateef and Al-Hasa22. A mild form of SCA was recognized in this part of Saudi Arabia. Studies conducted in different regions of Saudi Arabia (during 1970s to 1990′s) revealed the presence of HbS and other red cell genetic defects in several regions of the country23–29. Three major foci for HbS gene were identified in the country, and the frequency was found to correlate with the history of malaria endemicity. A comprehensive National screening programme initiated in 1982, covered 36 different areas, provided detailed mapping and distribution of HbS gene and revealed variation in the frequency in different areas of the country25–29. Extensive studies were conducted to trace the natural history of the SCD, and two major forms of the disease were identified, with symptoms ranging from mild to severe. Significant differences were observed in the HbF level in different patients. HbS gene was frequently shown to coexist with other abnormal Hbs, thalassaemias and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) deficiency. Studies on associated β-globin gene haplotypes revealed the presence of the Saudi-Indian haplotype in majority of the SCD patients from the Eastern province with a mild form of the disease and the Benin haplotype in majority of the patients from the Western province with a severe form of the disease16. Different treatment protocols were adopted and hydroxyurea and paracetam were shown to be beneficial for the treatment of SCD in majority of the patients. Control and prevention programs have been implemented and steps have been adopted to increase awareness about these frequent disorders23,25,27,28.

Bahrain: Several studies have been carried out on the SCD in Bahrain. In a study conducted during the 1986 on Bahrani girls, the incidence of sickle cell haemoglobin (Hb AS), was approximately 7 per cent30. In a group of 100 consecutive pregnant females, the frequency of HbSC was 17.5 per cent, and Hb AS was 32.5 per cent31. Patients with SCD were shown to have elevated Hb F levels, and double heterozygous HbS/β-thalassaemia cases were also identified32. In a large study on hospital population of Bahrain, which included 5,503 neonates and 50,695 non-neonates, the prevalence of SCD was reported as 2.1 per cent and HbS trait as 18.1 per cent in the neonates, and 10.44 per cent SCD in non-neonatal patients33. Al-Arrayed and coworkers34 conducted a screening of student for inherited blood disorders in Bahrain and reported the prevalence as 1.2 per cent SCD; 13.8 per cent Hb AS; 0.09 per cent beta-thalassaemia; 2.9 per cent β-thalassaemia trait. The majority (84%) of the SCD patients had elevated HbF. The Saudi-Indian haplotype was the major haplotype (90%) in the Bahrani SCD patients35. HbS was also reported to occur with other abnormal haemoglobins (e.g. HbS/D) in the population of Bahrain36, and a high percentage of the SCD patients (47%) had associated G-6-PD deficiency37.

Qatar: In 1985, Bakioglu and coworkers38 conducted screening of the Qatari population and reported the presence of HbS gene. In another screening study on 1,702 Qatari nationals, it was shown that 7.46 and 3.94 per cent were Hb AS and SCD patients, while 1.53 and 3.23 per cent of the patients had HbS/β-thalassaemia and HbS/α-thalassaemia, respectively39. The SCD was reported as mild with elevated HbF level though some patients suffered from episodes of crises39. Haplotype analysis also revealed the presence of Saudi-Indian haplotype.

Kuwait: In 1970, Ali reported sickle cell with a milder variant of the disease in Kuwaiti and showed that this was associated with unusually high levels of Hb F40. Molecular characterization of βS revealed the presence of Asian (Saudi-Indian) haplotype in 77.8 per cent and Benin haplotype in 16.7 per cent of the chromosomes41,42. Marouf et al43 conducted a comprehensive electrophoretic screening of the Kuwaiti population and showed that 23.5 per cent had abnormal haemoglobin genotypes, where Hb AS was 6 per cent, SCA was 0.9 per cent, HbS/β°thal was 0.8 per cent and HbSβ+ thal was 0.8 per cent.

United Arab Emirates (UAE): Among the UAE nationals abnormal HbS is one of the most common disorders. In 1984, Kamel44 described biochemical features of Arab SCA patients diagnosed over a 4-year period in Abu Dhabi. The frequency of SCD in the UAE was reported as 1.9 per cent in a major study conducted on 5000 subjects from three major Peninsular Arab States17. Miller et al45 conducted a haematological survey of preschool children and reported the frequency of HbS as 4.6 per cent. In a more recent survey Al Hosani et al46 reported the overall incidence of SCD among 22,200 screened neonates as 0.04 per cent (0.07% for UAE citizens and 0.02% for non-UAE citizens), where the incidence of Hb AS was overall 1.1 per cent (1.5% for UAE citizens and 0.8% for non-UAE citizens). Sickle cell anaemia and HbS/β thalassaemia were identified and cases of SCA with associated α-thalassaemia and G-6-PD deficiency were frequent. Wide variations were reported in the clinical features ranging from moderate to a severe disease, with elevated Hb F levels and associated α-thalassaemia44,47–49. Other investigators48,50 showed the presence of Saudi-Indian haplotype in 52 per cent of the βS chromosomes that was concurrent with the mild form of the disease.

Oman: In a study on 5000 subjects from three States of Arabian Peninsula, the frequency of SCD in Oman was reported as 3.8 per cent17. In addition, cases of HbS Omani, a variant of HbS were identified in a few families51–53. Rajab and co-workers54 reported the birth prevalence of symptomatic haemoglobinopathies in 23 Omani tribes through screening of a national register, as 1 in 323 live births or 3.1 per 1000 live births during 1989-1992, which included 2.7 per 1000 live births of homozygous SCD. It was calculated that each year, 118 new cases of SCD were expected to be born and HbAS frequency was 10 per cent. The regional distribution of SCD revealed that it was more prevalent (more than 70% of cases) in regions with smear-positive rates of malaria of 1 to >5 per cent (parts of Dhahira, Dakhliya, North and South Shargiya). Al-Riyami et al55 reported the overall prevalence of HbS as 5.8 per cent, though there were significant regional variations. Clinical variations in SCA presentation are largely related to the presence of different β-globin gene haplotypes identified during molecular studies, where Benin, Bantu and Saudi-Indian haplotypes were shown to be present in Oman52,56.

(ii) Arab countries in the northern region of Arabian Peninsula

Palestine: A study from Palestine on SCD reported HbS/ thalassaemia in a 12-year-old Palestinian boy with hand-foot syndrome57. Later studies have revealed a higher prevalence of β- thalasaemia, though a few cases of HbS and thalassaemia co-existing in the same patient have also been reported58. In a more recent study, it was shown that SCA has a severe clinical presentation and is accompanied by variable levels of HbF (1.5-17%; mean= 5.14%). Haplotype analysis shows that the Benin haplotype predominates with a frequency of 88.1 per cent, followed by the Bantu haplotype at a frequency of 5.1 per cent59,60.

Syria: The frequency of HbS is low (<1%) in Syria, though epidemiological studies are not available . Other abnormal variant that have been reported in the Syrians include the thalassaemias as also the molecular basis of the β-thalassaemic state61. A study on haplotypes associated with sickle cell gene has shown the presence of the Benin haplotype62.

Iraq: The first report of the presence of HbS gene in Iraq appeared in 1971 by Khutsishvili63. Thereafter, reports have shown that β-thalassaemia major and SCA are important health problems in Iraq. The frequency varies in the different areas, where a study in four villages of Abu-al-Khasib in Southern Iraq, on school children in the age group of 10 to 12 yr showed an overall HbS prevalence rate of 16 per cent as compared to 2.5 per cent seen in a control population of children belonging to five urban schools in Basrah and sickle cell trait was evident in 13.3 per cent of the cases64. In a recent study on population in Basra with age ranging from 14-60 yr, the HbS trait frequency was 3.24 per cent65. Associated G-6-PD deficiency was reported65 and the influence of haemoglobinopathies on growth and development was demonstrated66. Steps were adopted to implement control and prevention programs67.

Jordan: In a study conducted on 6-10 yr old school children in Northern Jordan Valley, both α- and β-thalassaemias and HbS were identified, though HbS gene frequency was very low (carrier frequency= 0.44%)68. Co-existing HbS/β-thalassaemias were identified, some with elevated Hb F level, but this did not ameliorate the SCA clinical presentations69. In a larger study in North Jordan, the overall prevalence of HbS and β-thalassaemia was 4.45 and 5.93 per cent, respectively and the incidence of Hb AS in the newborn sample was 3-6 per cent70,71. The prevalence of both HbS and beta-thalassaemia was higher in the Al-Ghor area in comparison to Ajloun and Irbid70. Variable clinical presentation of SCA has been reported and no correlation was demonstrated with Hb F level72.

Lebanon: Dabbous and Firzli73 reported the prevalence of HbS gene in Lebanon. The disease was shown to be clustered in two geographic areas in North and South Lebanon and nearly all patients were Muslims74. The disease was severe and the major haplotype was the Benin haplotype. Interestingly high levels of HbF were not shown to influence the clinical severity of SCA. As a result it was suggested that genetic factors other than haplotypes are the major determinants of increased HbF levels in SCD patients in Lebanon75. Considerable interest was geared towards management of SCA and on clinical trials using new agents to ameliorate the clinical presentation76.

(iii) The Arab countries of North Africa

Sudan: The first report of the presence of HbS gene in the Sudanese appeared in 195077. Later it was shown that the frequency of the gene varies significantly in different tribes78–81. In some areas sickle cell trait was present in 24 per cent of the newborn and 29 per cent of those aged over five years. The SCA presentation was severe and it was frequently fatal in early childhood and was accompanied with major complications81–84. Analysis of the haplotypes associated with the S gene indicated that the most abundant haplotypes are the Cameroon, Benin, Bantu and Senegal haplotypes85.

Egypt: Some researchers hypothesized that HbS gene was present among the predynastic Egyptian and they showed the presence of HbS in mummies (about 3200 BC)86. It was also suggested that HbS existed among the Egyptians from ancient times and the death of King Tutankhamun was due to SCA. However, this hypothesis was recently refuted87. The first case of SCA in Egypt was reported in 1951 by Abbasy88. Other abnormalities of haemoglobin were also identified89. Since then, several studies have been carried out and shown that, in Egypt, β-thalassaemia is the most common type with a carrier rate varying from 5.3-9 per cent and a gene frequency of 0.03. In Egypt, along the Nile Valley, the HbS gene is almost non existent, but in the western desert near the Libyan border variable rates of 0.38 per cent in the coastal areas to 9.0 per cent in the New Valley oases have been reported. HbS carrier rates vary from 9 to 22 per cent in some regions90. The SCD is severe with painful crises and other abnormalities91. Most of the globin gene haplotypes reported are the African haplotype62.

Algeria: In 1961, Juillan conducted a survey on the incidence of sickle-shaped erythrocytes in Algeria and reported the presence of HbS gene92. In 1977, Trabuchet et al93 showed the presence of genes for HbS, Hb C and thalassaemia in various regions of the country and reported that these genetic conditions were a major cause of severe congenital haemolytic anaemias. Co-existing HbS/thalassaemia, HbS/Hb C cases were also reported and HbSetif, Hb D Ouled Rabah were described for the first time in Algerians. In 1987, Dahmane-Arbane et al94 reported a case of Hb Boumerdes, an alpha chain variant (α2(37) (C2)Pro----Arg β2), in an Algerian family. The propositus was also homozygous for the HbS gene, though the sickle cell phenotype was benign. High Hb F level was reported in association with high Gγ/Aγ ratio and a comparison of the clinical and haematological characteristics in SCA and HbS/thalassaemia, showed that associated thalassaemias ameliorate the clinical presentation of SCD in Algerians95–97. Homozygous cases for haemoglobin J Mexico (alpha54 (E3)Gln replaced by Glu) have been reported98.

Tunisia: The first case of SCA was reported in a Tunisian family in 1967 by Ben Rachid et al99. Later studies showed that haemoglobin abnormalities constitute a major public health problem in many areas in Tunisia, including the central, North-western, Kebily in south Tunisia and the North-Kebili region100–104. The SCA is generally severe in Tunisians105–107 and haplotyping using nine restriction sites in the beta-globin gene cluster revealed that the most common haplotype is the Benin type which occurs at a frequency of over 94 per cent in SCD101,106,108. An atypical haplotype was also identified shedding light on multiple origins of HbS gene in Tunisia. The HbF level showed heterogeneity ranging from 2-16 per cent101,108 though the HbF Gγ gene expression was homogenous in patients with high or low Hb F108. A rare mildly unstable haemoglobin variant Hb Bab-Saadoun (α2β248(CD7)Leu----Pro, was reported in an Arabian boy from Tunisia109.

Libya: A screening study reported the presence of HbS, Hb C and thalassaemia genes in Libyans, but it was found that the incidence of abnormal haemoglobins in the indigenous population of Libya was low110. More recent studies confirmed that SCD occurs at a low frequency among Libyans111. The disease is associated with several complications and seems to be severe112,113.

Factors influencing the frequency of SCD

Sickle cell disease is widespread in the Middle Eastern Arab countries, although significant inter- and intra- countries differences are encountered in the frequencies of the abnormal genes. The main factors which are believed to play a major role in the increased frequencies of the HbS include:

(i) Consanguinity: The tradition of consanguineous marriage (inbreeding) goes far back in history and has been known in the Middle Eastern Arab countries from biblical times, where such marriages are not necessarily limited to geographic or religious isolates or ethnic minorities114. Several investigations have been conducted and reported high rates of consanguinity in most Middle Eastern Arab countries, though significant differences are encountered within the different countries and even between different tribes, communities, and ethnic groups within the same country. An average of about 30 per cent is seen in most Arab countries, though the prevalence of consanguinity ranges from about 25 per cent in Beirut115 to 60 per cent in Saudi Arabia and 90 per cent in some Bedouin communities in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia116,117. The most common form of inter-marriage is between first cousins, particularly paternal first cousins and includes double first-cousin marriage. In a study conducted on thalassaemics in Lebanon, it was reported that 49 per cent were offspring of first-cousin marriages, and it was suggested that consanguinity was responsible for the multiplication of the incidence of β-thalassaemia by a factor of 1.66118. Other studies in other countries have demonstrated various aspects of reproductive behaviour, reproductive wastage, increased morbidity and mortality, and increased prevalence of genetic defects in the offspring of consanguineous mating119. There are several contributing factors to this pattern, including the keenness of the people to keep the property within the family or tribe, and the attachment of people to their families or villages, the belief that cousin takes better care of each other117, and the popular belief that consanguineous marriage offers a major advantage in terms of compatibility of the bride and her husband's family, particularly her mother-in-law120.

(ii) Environmental factors: In the Middle Eastern countries, a major role is played by malaria endemicity in influencing the HbS gene frequency, like in other parts of the World11,121. The carriers of HbS have a natural resistance against malaria development and this is a major advantage to survival in adverse conditions. Several reports in the Middle Eastern Arab countries validated the “malaria hypothesis” by showing a close correlation between the frequencies of the abnormal gene and past and present history of malaria endemicity122–125.

(iii) Large sibship size: In general, the sibship size is large in the Middle Eastern Arab countries, e.g. in Saudi Arabia an average of 6-7 children/family is the norm. In families with the mutant genes a possible disadvantage is that a larger number of family members may have the abnormal genotype. This is demonstrated by several family examples126. In eight families in Algeria with an average of 6 children/family, Hb Jα-Mexico was found in 116 subjects127.

(iv) Migration: The rate of population migration between and within the different Middle Eastern Arab countries is high. To some extent this is caused by prevailing financial opportunities and job prospects. In the Gulf States, including Saudi Arabia, a large sector of the population is formed of immigrants’ workers, who have migrated from high-frequency areas, where they have established. Some have settled in these countries for decades, and as a result of inter-marriages, genetic admixtures have been generated. This gene drift has led to the establishment of the abnormal genes in several areas128.

Clinical presentation of SCD

The major symptoms of SCD are mild to severe anaemia, painful crises, frequent infections, hand and foot syndrome and stroke. Some patients require frequent blood transfusion, while others may never need a single transfusion during their lifetime. In severe form of SCD, the patients have retarded growth, bone defects, multiple organ dysfunction and other complications due to frequent transfusion requirements, while patients with a mild disease may reach average height and have no multiple organ abnormalities.

The SCD in different Middle Eastern Arab countries shows a significant variation in its clinical presentation. In Arabian Peninsula; Bahrain, UAE, Oman, Kuwait, and Qatar, the disease is generally mild with a mild to moderate anaemia and a few complications, though some patients have a severe disease requiring regular blood transfusions and hospitalization33,39,40,48,54. In Saudi Arabia, the eastern province shows similar mild pattern, while in the western part of the country, along the Red Sea, and Yemen, the severe pattern predominates16,28. In countries of North Africa, including the Sudan, Egypt, Libya, Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, most SCA patients have a severe disease, though cases with the mild form have also been reported59,82,91,93,97 (Table III).

Genetic factors contributing to the variability of SCA

The mutation in all SCD patients is the same GAG to GTG transversion in the 6th codon of the β globin gene. But clinically it is very diverse, ranging from a severe, life threatening state to a benign, almost asymptomatic form. Several genetic factors have been shown to be implicated in modulating the clinical presentation, where some ameliorate the disease while others have an augmenting influence. These are listed in the Fig..

Fig.

Possible factors influencing the clinical presentation of SCD.

It was suggested that co-existing genetic abnormalities, such as G-6-PD deficiency or the thalassaemias or other abnormal Hb variants, ameliorate the clinical presentation of SCD, thus producing a benign form of the disease129,130. In addition, the presence of an elevated level of Hb F was considered as an ameliorating factor131–133. The Saudi SCA patients in the eastern province were easily distinguishable from those of African origin by the mildness of clinical manifestations and the lower incidence of vaso-occlusive complications, persistence of splenic functions, lower morbidity due to other complications and lower risk during pregnancy. Amelioration was attributed to elevated Hb F in the Saudi patients. However, later studies revealed mild SCD, SCA or double heterozygotes, even in the absence of elevated levels of Hb F134–137.

Several studies confirmed the role of β- globin gene haplotypes in influencing the SCA clinical presentation138. If the HbS mutation takes place on a chromosome carrying the Saudi-Indian haplotype, the HbS generally gives rise to a mild form mostly with an elevated Hb F. The same mutation, if occurs on a chromosome carrying a Benin haplotype, is generally associated with lower Hb F levels and a severe disease139,140. Elevated Hb F levels clearly play a role in decreasing clinical severity, possibly through interfering with HbS sickling process. Associated α-thalassaemia also influences the severity of the disease and ameliorates the disease, but this depends also on the number of α-gene deleted or on the type of mutation producing the thalassaemic state. Presence of associated β-thalassaemia influences the clinical presentation, and is dictated by the nature of β-thalassaemia mutation. β+ mutations producing HbS/β+ thalassaemia state have an ameliorating effect, while β° mutations result in HbS/ β°-thalassaemia and this state may be equally severe as SCA. The role of presence of different polymorphic sites (Xmn 1 polymorphic site 5’ to Gγ gene and Hpa1 polymorphic site 3’ to β gene), is also generally believed to be an ameliorating factor. Studies on the effect of Hb F, and Gγ/Aγ ratio have demonstrated that patients with a mild disease generally have a high ratio, while the reverse is true in patients with a severe disease141–146. Contradictions are frequent when it comes to associated G-6-PD deficiency, where both ameliorating effects and adverse effects have been reported in studies reported from the Middle Eastern Arab countries. There may be several other, yet unidentified genetic loci which also influence the SCD clinical presentation, since many patients who do not carry Saudi-Indian haplotype, or elevated Hb F level or the other possible ameliorating factors have a mild disease or vice versa136–146.

Management strategies

There is a significant diversity in management protocols applied for the SCA and SCD patients in the different Middle Eastern countries due to diversity of the clinical presentations and risk factors and the status of health care. It is well documented that comprehensive and regular medical care plays an important role in the well being and normal survival of SCA patients. In some of the countries the care is near optimal, while the reverse is true in others. The management protocols for SCA patients have been slightly modulated to reach the most appropriate protocol. In some centres early diagnosis is emphasized and is followed by pneumococcal vaccination and penicillin prophylaxis, to prevent infections. Acute painful crisis is common sequel that can cause significant morbidity and negatively impact the patient's quality of life. Proper nutrition and health care play an important role besides avoiding the factors that may cause crisis, such as low temperature, dehydration, high fever and infections. Patients suffering from crisis may be hospitalized and are often transfused. The most common analgesics are paracetamol, Voltaren and morphine sulphate147. However, some studies reported that adults with painful conditions often receive inadequate or no analgesic treatment148. Splenectomy is frequently carried out for SCA patients where indications for splenectomy are recurrent acute splenic sequestration and hypersplenism. In general, splenectomy has been beneficial in eliminating the risk of splenic sequestration in SCA patients and in improving the blood counts in SCA with hypersplenism149.

Several investigators have used agents that may elevate Hb F level and hence decrease disease severity. Hydroxyurea has been successfully used and established for treatment of SCA and HbS/β- thalassaemia patients150–152. Paracetam has been used successfully in children as a drug that helps reduce painful crises and improve blood circulation153. Bone marrow transplantation for suitable patients is carried out in specialized centres and recent reports demonstrated the usefulness of stem cell transplantation.

Steps towards control and prevention

Both SCA and SCD pose health problems in most of the Middle Eastern Arab countries. Beside the need for care and rehabilitation for the affected patients, effective strategies for control and prevention were recognized as an essential measure toward decreasing the birth of affected children (primary prevention). For a successful control programme, education, counselling and increasing the awareness of chronicity of SCA condition are essential approaches. Several countries have adopted effective steps directed toward prevention154–160, such as (i) community screening and school screening programme have been implemented; (ii) inclusion of relevant information in the school curricula has been adopted; and (iii) articles published in newspapers, talk shows on the radio and TV, workshops and symposia and special days for SCA are held to improve the awareness of the general public and the health care providers. An effective preventive programme was the premarital screening, which has been adopted in some of the countries, including Saudi Arabia160. The programme was initiated in 1998 and was implemented in a step-wise manner. The programme was complemented by genetic counselling services for the carriers and the diseased and offered by trained counsellors and wedding authorities. These services are expected to increase awareness and provide equitable access to health services, improve quality of life of those affected and help achieve primary, secondary and tertiary prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding the work through the research group project No. RGP-VPP-068.

References

- 1.Gelehrter TD, Collins FS, Ginsburg D. London: Williams & Wilkins; 1998. Principles of medical genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alwan A, Modell B. Alexandria. VA: World Health Organization; 1997. Community control of genetic and congenital disorders. Eastern Mediterranean Region Office Technical Publication Series 24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perutz MF. Structure of haemoglobin”. Brookhaven Symp Biol. 1960;13:165–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weatherall D, Clegg JB. The thalassaemia syndrome. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrone F, Nagel RL. Sickle hemoglobin polymerization. In: Steinberg MH, Forget BG, Higgs D, Nagel, editors. Disorders of hemoglobin: Genetics, pathophysiology, clinical management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaul DK, Fabry ME, Nagel RL. Microvascular sites and characteristics of sickle cell adhesion to vascular endothelium in shear flow conditions: pathophysiological implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3356–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg MH, Forget BG, Higgs D, Nagel, editors. Disorders of hemoglobin: Genetics, pathophysiology, clinical management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caughey WS. New York: Academic Press; 1978. Biochemical and clinical aspects of hemoglobin abnormalities. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonarakis SE, Orkin SH, Kazazian HH, Jr, Goff SC, Boehm CD, Waber PG, et al. Evidence for multiple origins of the beta-globin gene in Southeast Asia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6608–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pagnier J, Mears JG, Dunda-Belkhodja O, Schaefer-Rego KE, Beldjord C, Nagel RL, et al. Evidence for the multicentric origin of the sickle cell hemoglobin gene in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1771–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piel FB, Pati APl, Howes RE, Nyangiri OE, Gething PW, Williams TN, et al. Global distribution of the sickle cell gene and geographical confirmation of the malaria hypothesis. Nat Commun. 2010;1:104–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huisman THJ, Carver MFH, Efremov GD. A syllabus of human hemoglobin variants. GA, USA: The Sickle Cell Anemia Foundation in Augusta; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diwani M. Erythroblastic anaemia with bone changes in Egyptian children.Possibly Cooleys anaemia. Arch Dis Child. 1944;19:163–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.19.100.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbasy AS. Sickle cell anemia; first case reported from Egypt. Blood. 1951;6:555–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehmann H. Variations in human haemoglobin synthesis and factors governing their inheritance. Br Med Bull. 1959;15:40–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a069712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Hazmi MAF, Warsy AS. Hemoglobinopathies in Arab countries. In: Teebi AS, Farag TL, editors. Genetic disorders among Arab populations. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- 17.White JM, Byrne M, Richards R, Buchanan T, Katsoulis E, Weerasingh K. Red cell genetic abnormalities in Peninsular Arabs: sickle haemoglobin, G6PD deficiency, and alpha and beta thalassaemia. J Med Genet. 1986;23:245–51. doi: 10.1136/jmg.23.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Saqladi AW, Brabin BJ, Bin-Gadeem HA, Kanhai WA, Phylipsen M, Harteveld CL. Beta-globin gene cluster haplotypes in Yemeni children with sickle cell disease. Acta Haematol. 2010;123:182–5. doi: 10.1159/000294965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS. Molecular studies on Yemeni sickle-cell-disease patients: Xmn I polymorphism. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:1183–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS. Pattern for alpha-thalassaemia in Yemeni sickle-cell-disease patients. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:1159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehmann H, Maranjian G, Mourant AE. Distribution of sickle-cell hemoglobin in Saudi Arabia. Nature. 1963;198:492–3. doi: 10.1038/198492b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelpi AP. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, the sickling trait, and malaria in Saudi Arab children. J Pediatr. 1967;71:138–46. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(67)80246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Hazmi MA. On the nature of sickle-cell disease in the Arabian Peninsula. Hum Genet. 1979;52:323–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00278681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Hazmi MA, Lehmann H. Human haemoglobins and haemoglobinopathies in Arabia: Hb O Arab in Saudi Arabia. Acta Haematol. 1980;63:268–73. doi: 10.1159/000207414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Hazmi MA. Haemoglobin disorders: a pattern for thalassaemia and haemoglobinopathies in Arabia. Acta Haematol. 1982;68:43–51. doi: 10.1159/000206947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El -Hazmi MA, Warsy AS, al-Swailem AR, al-Swailem AM, Bahakim HM. Sickle cell gene in the population of Saudi Arabia. Hemoglobin. 1996;20:187–98. doi: 10.3109/03630269609027928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS. Appraisal of sickle-cell and thalassaemia genes in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:1147–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Hazmi MA. Haemoglobinopathies, thalassaemias and enzymopathies in Saudi Arabia: the present status. Acta Haematol. 1987;78:130–4. doi: 10.1159/000205861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Qurashi MM, El-Mouzan MI, Al-Herbish AS, Al-Salloum AA, Al-Omar AA. The prevalence of sickle cell disease in Saudi children and adolescents. A community-based survey. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:1480–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blair D, Gregory WB. Nutritional vs hereditary anaemias appropriate screening procedures for Bahrain. Bahrain Med Bull. 1986;8:124–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Shafei AM, Rao PS, Sandhu AK. Pregnancy and sickle cell hemoglobinopathies in Bahrain. Saudi Med J. 1988;3:283–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buhazza MA, Bikhazi AB, Khouri FP. Evaluation of haematological findings in 50 Bahraini patients with sickle cell disease and in some of their parents. J Med Genet. 1985;22:293–5. doi: 10.1136/jmg.22.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al Arrayed SS, Haites N. Features of sickle-cell disease in Bahrain. East Mediterr Health J. 1995;1:112–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Arrayed S, Hafadh N, Amin S, Al-Mukhareq H, Sanad H. Student screening for inherited blood disorders in Bahrain. East Mediterr Health J. 2003;9:344–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Arrayed SS. Beta globin gene haplotypes in Bahraini patients with sickle cell anaemia. Bahrain Med Bull. 1995;17:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dash S. Hemoglobin S-D disease in a Bahraini child. Bahrain Med Bull. 1995;17:154–5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohammad AM, Ardatl KO, Bajakian KM. Sickle cell disease in Bahrain: coexistence and interaction with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. J Trop Pediatr. 1998;44:70–2. doi: 10.1093/tropej/44.2.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakioglu I, Hattori Y, Kutlar A, Mathew C, Huisman TH. Five adults with mild sickle cell anemia share a beta S chromosome with the same haplotype. Am J Hematol. 1985;20:297–300. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830200313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fawzi ZO, Al-Hilali A, Fakhroo N, Al-Bin-Ali A, Al-Mansour S. Distribution of hemoglobinopathies and thalassemias in Qatari nationals seen at Hamad hospital in Qatar. Qatar Med J. 2003;12:20–4. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali SA. Milder variant of sickle-cell disease in Arabs in Kuwait associated with unusually high level of foetal haemoglobin. Br J Haematol. 1970;19:613–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1970.tb01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adekile AD, Gu LH, Baysal E, Haider MZ, al-Fuzae L, Aboobacker KC, et al. Molecular characterization of alpha-thalassemia determinants, beta-thalassemia alleles and beta S haplotypes among Kuwaiti Arabs. Acta Haematol. 1994;92:176–81. doi: 10.1159/000204216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adekile AD, Haider MZ. Morbidity, beta S haplotype and alpha-globin gene patterns among sickle cell anemia patients in Kuwait. Acta Haematol. 1996;96:150–4. doi: 10.1159/000203753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marouf R, D’souza TM, Adekile AD. Hemoglobin electrophoresis and hemoglobinopathies in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2002;11:38–41. doi: 10.1159/000048659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamel K. Sickle cell hemoglobin: origin and clinical manifestations in Arabs and relation to fetal hemoglobin levels. Qatar Med J. 1984;5:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller CJ, Dunn EV, Berg B, Abdouni SF. A hematological survey of preschool children of the United Arab Emirates. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:609–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al Hosani H, Salah M, Osman HM, Farag HM, Anvery SM. Incidence of haemoglobinopathies detected through neonatal screening in the United Arab Emirates. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11:300–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Awaad MO, Bayoumi R. Sickle cell disease in adult Bedouins of Al-Ain district, United Arab Emirates. Emirates Med J. 1993;11:21–4. [Google Scholar]

- 48.El-Kalla S, Baysal E. Genotype-phenotype correlation of sickle cell disease in the United Arab Emirates. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1998;15:237–42. doi: 10.3109/08880019809028790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller CJ, Dunn EV, Berg B, Abdouni SF. A hematological survey of preschool children of the United Arab Emirates. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:609–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baysal E. Hemoglobinopathies in the United Arab Emirates. Hemoglobin. 2001;25:247–53. doi: 10.1081/hem-100104033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagel RL, Daar S, Romero JR, Suzuka SM, Gravell D, Bouhassira E, et al. HbS-oman heterozygote: a new dominant sickle syndrome. Blood. 1998;92:4375–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suresh V, Asila NS, Nafisa MZ, Laitha MN, Susamma M. Haemoglobin S Oman trait- A sickling variant. Oman Med J. 1999;16:23–4. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al Jahdhamy R, Makki H, Farrell G, Al Azzawi S. A case of compound heterozygosity for Hb S and Hb S Oman. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:504. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1048.2001.03284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rajab AG, Patton MA, Modell B. Study of hemoglobinopathies in Oman through a national register. Saudi Med J. 2000;21:1168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al-Riyami AA, Suleiman AJ, Afifi M, Al-Lamki ZM, Daar S. A community-based study of common hereditary blood disorders in Oman. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7:1004–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daar S, Hussain HM, Gravell D, Nagel RL, Krishnamoorthy R. Genetic epidemiology of HbS in Oman: multicentric origin for the betaS gene. Am J Hematol. 2000;64:39–46. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(200005)64:1<39::aid-ajh7>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fathalla M. Unusual age of presentation of hand-foot syndrome. Emirates Med J. 1986;4:143–5. [Google Scholar]

- 58.El-Latif MA, Filon D, Rund D, Oppenheim A, Kanaan M. The beta+-IVS-I-6 (T-->C) mutation accounts for half of the thalassemia chromosomes in the Palestinian populations of the mountain regions. Hemoglobin. 2002;26:33–40. doi: 10.1081/hem-120002938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Samarah F, Ayesh S, Athanasiou M, Christakis J, Vavatsi N. beta(S)-Globin gene cluster haplotypes in the West Bank of Palestine. Hemoglobin. 2009;33:143–9. doi: 10.1080/03630260902861873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Darwish HM, El-Khatib FF. Ayesh Spectrum of beta-globin gene mutations among thalassemia patients in the West Bank region of Palestine. Hemoglobin. 2005;29:119–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kyriacou K, Al Quobaili F, Pavlou E, Christopoulos G, Ioannou P, Kleanthous M. Molecular characterization of beta-thalassemia in Syria. Hemoglobin. 2000;24:1–13. doi: 10.3109/03630260009002268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.El-Hazmi MAF, Warsy AS, Bashir N, Beshlawi A, Hussain IR, Temtamy S, et al. Haplotypes of the beta-globin gene as prognostic factors in sickle-cell disease. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:1154–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khutsishvili GE. Current concepts on the structure of normal and pathologic hemoglobins (review of the literature) Lab Delo. 1971;8:454–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alkasab FM, Al-Alusi FA, Adnani MS, Alkafajei AM, Al-Shakerchi NH, Noori SF. The prevalence of sickle cell disease in Abu-AL-Khasib district of southern Iraq. J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;84:77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hassan MK, Taha JY, Al-Naama LM, Widad NM, Jasim SN. Frequency of haemoglobinopathies and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in Basra. East Mediterr Health J. 2003;9:45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mansour AA. Influence of sickle hemoglobinopathy on growth and development of young adult males in Southern Iraq. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:544–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al-Allawi NA, Al-Dousky AA. Frequency of haemoglobinopathies at premarital health screening in Dohuk, Iraq: implications for a regional prevention programme. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:381–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bashir N, Barkawi M, Sharif L. Prevalence of haemoglobinopathies in school children in Jordan Valley. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1991;11:373–6. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1991.11747532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bashir N, Barkawi M, Sharif L. Sickle cell/beta-thalassemia in North Jordan. J Trop Pediatr. 1992;38:196–8. doi: 10.1093/tropej/38.4.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sunna EI, Gharaibeh NS, Knapp DD, Bashir NA. Prevalence of hemoglobin S and beta-thalassemia in northern Jordan. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 1996;22:17–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1996.tb00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Talafih K, Hunaiti AA, Gharaibeh N, Gharaibeh M, Jaradat S. The prevalence of hemoglobin S and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in Jordanian newborn. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 1996;22:417–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1996.tb01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.al-Sheyyab M, Rimawi H, Izzat M, Batieha A, el Bashir N, Almasri N, et al. Sickle cell anaemia in Jordan and its clinical patterns. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1996;16:249–53. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1996.11747834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dabbous IA, Firzli SS. Sickle cell anemia in Lebanon - its predominance in the Mohammedans. Z Morphol Anthropol. 1968;59:225–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Inati A, Jradi O, Tarabay H, Moallem H, Rachkidi Y, El Accaoui R, et al. Sickle cell disease: the Lebanese experience. Int J Lab Hematol. 2007;29:399–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2007.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Inati A, Taher A, Bou Alawi W, Koussa S, Kaspar H, Shbaklo H, et al. Beta-globin gene cluster haplotypes and HbF levels are not the only modulators of sickle cell disease in Lebanon. Eur J Haematol. 2003;70:79–83. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abboud MR, Musallam KM. Sickle cell disease at the dawn of the molecular era. Hemoglobin. 2009;33(Suppl 1):S93–S106. doi: 10.3109/03630260903347617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abbott PH. The sickle cell trait among the Zande tribe of the southern Sudan. East Afr Med J. 1950;27:162–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Foy H, Kondi A, Timms GL, Brass W, Bishra F. The variability of sickle-cell rates in the tribes of Kenya and the Southern Sudan. Br Med J. 1954;1:294–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4857.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ibrahim SA. Sickle-cell thalassaemia disease in Sudanese. East Afr Med J. 1970;47:47–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Omer A, Ali M, Omer AH, Mustafa MD, Satir AA, Samuel AP. Incidence of G-6-PD deficiency and abnormal haemoglobins in the indigenous and immigrant tribes of the Sudan. Trop Geogr Med. 1972;24:401–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fleming AF, Storey J, Molineaux L, Iroko EA, Attai ED. Abnormal haemoglobins in the Sudan savanna of Nigeria. I. Prevalence of haemoglobins and relationships between sickle cell trait, malaria and survival. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1979;73:161–72. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1979.11687243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bayoumi RA, Abu Zeid YA, Abdul Sadig A, Awad Elkarim O. Sickle cell disease in Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1988;82:164–8. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(88)90298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mohamed AO, Bayoumi RA, Hofvander Y, Omer MI, Ronquist G. Sickle cell anaemia in Sudan: clinical findings, haematological and serum variables. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:131–6. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1992.11747557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mohamed AO. Sickle cell disease in the Sudan. Clinical and biochemical aspects. Minireview based on a doctoral thesis. Ups J Med Sci. 1992;97:201–28. doi: 10.3109/03009739209179297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mohammed AO, Attalla B, Bashir FM, Ahmed FE, El Hassan AM, Ibnauf G, et al. Relationship of the sickle cell gene to the ethnic and geographic groups populating the Sudan. Community Genet. 2006;9:113–20. doi: 10.1159/000091489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marin A, Cerutti N, Massa ER. Use of the amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS) in the study of HbS in predynastic Egyptian remains. Boll Soc Ital Biol Sper. 1999;75:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pays JF. Tutankhamun and sickle-cell anaemia. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2010;103:346–7. doi: 10.1007/s13149-010-0095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Abbasy AS. Sickle cell anemia; first case reported from Egypt. Blood. 1951;6:555–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Awny AY, Kamel K, Hoerman KC. ABO blood groups and hemoglobin variants among Nubians, Egypt, U.A.R. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1965;23:81–2. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330230129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.El-Beshlawy A, Youssry I. Prevention of hemoglobinopathies in Egypt. Hemoglobin. 2009;33(Suppl 1):S14–20. doi: 10.3109/03630260903346395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Soliman AT, elZalabany M, Amer M, Ansari BM. Growth and pubertal development in transfusion-dependent children and adolescents with thalassaemia major and sickle cell disease: a comparative study. J Trop Pediatr. 1999;45:23–30. doi: 10.1093/tropej/45.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Juillan M. Survey on the incidence of sickle-shaped erythrocytes in Algeria. Arch Inst Pasteur Alger. 1961;39:261–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Trabuchet G, Dahmane M, Benabadji M. Abnormal hemoglobins in Algeria. Sem Hop. 1977;53:879–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dahmane-Arbane M, Blouquit Y, Arous N, Bardakdjian J, Benamani M, Riou J, et al. [Hemoglobin Boumerdès alpha 2(37) (C2) Pro----Arg beta 2: a new variant of the alpha chain associated with hemoglobin S in an Algerian family] Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1987;29:317–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Labie D, Pagnier J, Lapoumeroulie C, Rouabhi F, Dunda-Belkhodja O, Chardin P, et al. Common haplotype dependency of high G gamma-globin gene expression and high Hb F levels in beta-thalassemia and sickle cell anemia patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2111–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.7.2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pagnier J, Dunda-Belkhodja O, Zohoun I, Teyssier J, Baya H, Jaeger G, et al. alpha-Thalassemia among sickle cell anemia patients in various African populations. Hum Genet. 1984;68:318–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00292592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Haj Khelil A, Denden S, Leban N, Daimi H, Lakhdhar R, Lefranc G, et al. Hemoglobinopathies in North Africa: a review. Hemoglobin. 2010;34:1–23. doi: 10.3109/03630260903571286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Trabuchet G, Pagnier J, Benabadji M, Labie D. Homozygous cases for hemoglobin J Mexico (alpha54 (E3)Gln replaced by Glu) evidence for a duplicated alpha gene with unequal expression. Hemoglobin. 1976-1977;1:13–25. doi: 10.3109/03630267609031019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ben Rachid MS, Farhat M, Brumpt LC. Hemoglobin S disease in Tunisia. Apropos of a familial case with a study of the family tree] Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1967;7:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mseddi S, Gargouri J, Labiadh Z, Kassis M, Elloumi M, Ghali L, et al. Prevalence of hemoglobin abnormalities in Kebili (Tunisian South)] Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1999;47:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Frikha M, Fakhfakh F, Mseddi S, Gargouri J, Ghali L, Labiadh Z, et al. Hemoglobin beta S haplotype in the Kebili region (southern Tunisia)] Transfus Clin Biol. 1998;5:166–72. doi: 10.1016/s1246-7820(98)80006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Znaidi R, Hafsia R, Megid M, M’Rad A, Kastally R, Hafsia A. [Hemoglobinopathies in Nefza: a model of health intervention] Tunis Med. 1996;74:33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chebil-Laradi S, Pousse H, Khelif A, Ghanem N, Martin J, Kortas M, et al. Screening of hemoglobinopathies and molecular analysis of beta-thalassemia in Central Tunisia. Arch Pediatr. 1994;1:1100–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Haj Khelil A, Laradi S, Miled A, Omar Tadmouri G, Ben Chibani J, Perrin P. Clinical and molecular aspects of haemoglobinopathies in Tunisia. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;340:127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fattoum S. Hemoglobinopathies in Tunisia. An updated review of the epidemiologic and molecular data. Tunis Med. 2006;84:687–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fattoum S, Guemira F, Oner C, Oner R, Li HW, Kutlar F, Huisman TH. Beta-thalassemia, HB S-beta-thalassemia and sickle cell anemia among Tunisians. Hemoglobin. 1991;15:11–21. doi: 10.3109/03630269109072481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mellouli F, Bejaoui M. The use of hydroxyurea in severe forms of sickle cell disease: study of 47 Tunisian paediatric cases. Arch Pediatr. 2008;15:24–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Abbes S, Fattoum S, Vidaud M, Goossens M, Rosa J. Sickle cell anemia in the Tunisian population: haplotyping and HbF expression. Hemoglobin. 1991;15:1–9. doi: 10.3109/03630269109072480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Molchanova TP, Wilson JB, Gu LH, Guemira F, Fattoum S, Huisman TH. Hb Bab-Saadoun or alpha 2 beta (2)48(CD7)Leu----Pro, a mildly unstable variant found in an Arabian boy from Tunisia. Hemoglobin. 1992;16:267–73. doi: 10.3109/03630269208998867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jain RC. Haemoglobinopathies in Libya. J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;82:128–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jain RC. Sickle cell and thalassaemic genes in Libya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79:132–3. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Radhakrishnan K, Thacker AK, Maloo JC, el-Mangoush MA. Sickle cell trait and stroke in the young adult. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:1078–80. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.782.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.el Mauhoub M, el Bargathy S, Sabharwal HS, Aggarwal VP, el Warrad K. Priapism in sickle cell anaemia: a case report. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1991;1:371–2. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1991.11747531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kamal H. 1st ed. Cairo: National Publishing House; 1967. Dictionary of pharaonic medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Khlat M, Khudr A. Cousin marriages in Beirut, Lebanon: is the pattern changing? J Biosoc Sci. 1984;16:369–73. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000015182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Al-Roshoud R, Farid S. Kuwait: Ministry of Health Publication; 1991. Kuwait Health Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Panter-Brick C. Parental responses to consanguinity and genetic disease in Saudi Arabia. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:1295–302. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90078-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Basson PM. Genetic disease and culture patterns in Lebanon. J Biosoc Sci. 1979;11:201–7. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000012256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Khlat H. Endogamy in the Arab World. In: Teebi AS, Faraj TI, editors. Genetic disorders among Arab population. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jaber L, Bailey-Wilson JE, Haj-Yehia M, Hernandez J, Shohat M. Consanguineous matings in an Israeli-Arab community. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:412–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170040078013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Livingstone FB. Sickling and malaria. Br Med J. 1957;1:762–3. [Google Scholar]

- 122.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS. On the nature of sickle cell disease in the south-western province of Saudi Arabia. Acta Haematol. 1986;76:212–6. doi: 10.1159/000206058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.El-Hazmi MA. Clinical and haematological diversity of sickle cell disease in Saudi children. J Trop Pediatr. 1992;38:106–12. doi: 10.1093/tropej/38.3.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS. The frequency of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase phenotypes and sickle cell genes in Al-Qatif oasis. Ann Saudi Med. 1994;14:491–4. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1994.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS, Bahakim HH, al-Swailem A. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and the sickle cell gene in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. J Trop Pediatr. 1994;40:12–6. doi: 10.1093/tropej/40.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Deeb ME, Sayegh LG. Genetic disorders among Arab population. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. Population dimensions in the Arab world; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Trabuchet G, Benabadji M, Labie D. Genetic and biosynthetic studies of families carrying hemoglobin J alpha Mexico: association of alpha-thalassemia with HbJ. Hum Genet. 1978;42:189–99. doi: 10.1007/BF00283639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Baghernajad-Salehi L, D’Apice MR, Babameto-Laku A, Biancolella M, Mitre A, Russo S, et al. Pilot beta-thalassaemia screening program in the Albanian population for a health planning program. Acta Haematol. 2009;121:234–8. doi: 10.1159/000226423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB, Blankson J, McNeil JR. A new sickling disorder resulting from interaction of the genes for haemoglobin S and alpha-thalassaemia. Br J Haematol. 1969;17:517–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1969.tb01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gelpi AP. Sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabs. Acta Haematol. 1970;43:89–99. doi: 10.1159/000208718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pembrey ME, Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB, Bunch C, Perrine RP. Haemoglobin Bart's in Saudi Arabia. Br J Haematol. 1975;29:221–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1975.tb01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pembrey ME, Wood WG, Weatherall DJ, Perrine RP. Fetal haemoglobin production and the sickle gene in the oases of Eastern Saudi Arabia. Br J Haematol. 1978;40:415–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1978.tb05813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Perrine RP, Brown MJ, Clegg JB, Weatherall DJ, May A. Benign sickle-cell anaemia. Lancet. 1972;2:1163–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92592-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.El-Hazmi MA, Bahakim HM, al-Swailem AM, Warsy AS. The features of sickle cell disease in Saudi children. J Trop Pediatr. 1990;36:148–55. doi: 10.1093/tropej/36.4.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS. A comparative study of haematological parameters in children suffering from sickle cell anaemia (SCA) from different regions of Saudi Arabia. J Trop Pediatr. 2001;47:136–41. doi: 10.1093/tropej/47.3.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.El-Hazmi MA. Clinical and haematological diversity of sickle cell disease in Saudi children. J Trop Pediatr. 1992;38:106–12. doi: 10.1093/tropej/38.3.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.El-Hazmi MA. Heterogeneity and variation of clinical and haematological expression of haemoglobin S in Saudi Arabs. Acta Haematol. 1992;88:67–71. doi: 10.1159/000204654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Powars DR. Sickle cell anemia: beta S-gene-cluster haplotypes as prognostic indicators of vital organ failure. Semin Hematol. 1991;28:202–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.El-Hazmi MA, Bahakim HM, Warsy AS. DNA polymorphism in the beta-globin gene cluster in Saudi Arabs: relation to severity of sickle cell anaemia. Acta Haematol. 1992;88:61–6. doi: 10.1159/000204653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.El-Hazmi MA. Beta-globin gene polymorphism in the Saudi Arab population. Hum Genet. 1986;73:31–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00292660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS. On the molecular interactions between alpha-thalassaemia and sickle cell gene. J Trop Pediatr. 1993;39:209–13. doi: 10.1093/tropej/39.4.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.El-Hazmi MA. Xmn I polymorphism in the gamma-globin gene region among Saudis. Hum Hered. 1989;39:12–9. doi: 10.1159/000153825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.El-Hazmi MA, Bahakim HM, Warsy AS, al-Momen A, al-Wazzan A, al-Fawwaz I, et al. Does G gamma/A gamma ratio and Hb F level influence the severity of sickle cell anaemia. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;124:17–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01096377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.El-Hazmi MA, al-Swailem AR, Bahakim HM, al-Faleh FZ, Warsy AS. Effect of alpha thalassaemia, G-6-PD deficiency and Hb F on the nature of sickle cell anaemia in south-western Saudi Arabia. Trop Geogr Med. 1990;42:241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.El-Hazmi MA. Clinical manifestation and laboratory findings of sickle cell anaemia in association with alpha-thalassaemia in Saudi Arabia. Acta Haematol. 1985;74:155–60. doi: 10.1159/000206194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS, Addar MH, Babae Z. Fetal haemoglobin level - effect of gender, age and haemoglobin disorders. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;135:181–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00926521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Taha HM, Rehmani RS. Pain management of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease presenting to the emergency department. Saudi Med J. 2011;32:152–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Rehmani RS. Pain practices in a Saudi emergency department. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:539–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Machado NO, Grant CS, Alkindi S, Daar S, Al-Kindy N, Al Lamki Z, et al. Splenectomy for haematological disorders: a single center study in 150 patients from Oman. Int J Surg. 2009;7:476–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.El-Hazmi MA, al-Momen A, Warsy AS, Kandaswamy S, Huraib S, Harakati M, et al. The pharmacological manipulation of fetal haemoglobin: trials using hydroxyurea and recombinant human erythropoietin. Acta Haematol. 1995;93:57–61. doi: 10.1159/000204112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.El-Hazmi MA, al-Momen A, Kandaswamy S, Huraib S, Harakati M, al-Mohareb F, et al. On the use of hydroxyurea/erythropoietin combination therapy for sickle cell disease. Acta Haematol. 1995;94:128–34. doi: 10.1159/000203994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS, al-Momen A, Harakati M. Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell disease. Acta Haematol. 1992;88:170–4. doi: 10.1159/000204681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.El-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS, al-Fawaz I, Opawoye AO, Taleb HA, Howsawi Z, et al. Piracetam is useful in the treatment of children with sickle cell disease. Acta Haematol. 1996;96:221–6. doi: 10.1159/000203788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Al Arrayed S, Al Hajeri A. Public awareness of sickle cell disease in Bahrain. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30:284–8. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.65256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Al Arrayed S. Campaign to control genetic blood diseases in Bahrain. Community Genet. 2005;8:52–5. doi: 10.1159/000083340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Al-Allawi NA, Al-Dousky AA. Frequency of haemoglobinopathies at premarital health screening in Dohuk, Iraq: implications for a regional prevention programme. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:381–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Al Sulaiman A, Saeedi M, Al Suliman A, Owaidah T. Postmarital follow-up survey on high risk patients subjected to premarital screening program in Saudi Arabia. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30:478–81. doi: 10.1002/pd.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Al-Shahrani M. Steps toward the prevention of hemoglobinopathies in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Hemoglobin. 2009;33(Suppl 1):S21–4. doi: 10.3109/03630260903346437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.El-Beshlawy A, Youssry I. Prevention of hemoglobinopathies in Egypt. Hemoglobin. 2009;33(Suppl 1):S14–20. doi: 10.3109/03630260903346395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.El-Hazmi MA. Spectrum of genetic disorders and the impact on health care delivery: an introduction. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:1104–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]