Abstract

Background:

Leprosy a chronic infectious affliction, is a communicable disease that posses a risk of permanent and progressive disability. The associated visible deformities and disabilities have contributed to the stigma and discrimination experienced by leprosy patients, even among those who have been cured.

Aims and Objectives:

1) To assess the knowledge, attitude and belief about leprosy in leprosy patients compared with community members. 2) To find the perceived stigma among leprosy patients. 3). To evaluate the quality of life in leprosy patients as compared to community members using WHO Quality of Life assessment questionaire (WHOQOL- BREF).

Materials and Methods:

A cross sectional study was conducted at Leprosy Rehabilitation Centre, Shantivan, Nere in Panvel Taluka, district Raigad from October – December 2009. A pre-designed and pre-structured questionaire was used to evaluate knowledge, attitude and perceived stigma among leprosy patients and community members. WHO Quality of life questionaire (WHOQOL-BREF) was used to assess quality of life in leprosy patients and controls. Data analysis was done with the help of SPSS package.

Result:

Among the cases and control, 43.13% of cases were aware that leprosy is an infectious disease compared to 20.69% of control. 68.62% of cases had knowledge of hypopigmented patches being a symptom of leprosy compared to the 25.86% in control. There was overall high level of awareness about disease, symptoms, transmission and curability in leprosy patients as compared to control. Among control group, 43.10% of population said that they would not like food to be served by leprosy patients as compared to 13.73% in study group. It was seen that the discrimination was much higher in female leprosy patients as compared to male leprosy patients. The mean quality of life scores for cases was significantly lower than those for control group in physical and psychological domain but not in the social relationship and environmental domain. The mean quality of life scores for male cases were lower in each domain as compared to male control group but the difference was not significant except in the physical and enviornmental domain. The mean quality of life scores for female cases were lower in each domain as compared to female control group and the difference was not significant except in the psychological domain.

Conclusions:

There was a significant difference in physical domain in male leprosy patients and psychological domain in female leprosy patients as compared with their respective gender controls. The leprosy patients were more aware about the infectious nature of the disease, symptoms, transmission, and curability than the control group. A negative attitude was seen towards the leprosy patients in the society.

Keywords: Discrimination, KAP, Leprosy, Perceived stigma, Quality of life, Stigma

INTRODUCTION

Leprosy has been widely prevalent in India for centuries. India has always been the country with the largest number of leprosy cases in the world.[1] Although the burden of leprosy has reduced many folds over the years, it would be important to ensure that leprosy is kept on the health agenda in order to sustain the elimination in those states that have already achieved it, while efforts need to be redoubled in states where the goal has yet to be achieved.

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease, which, if untreated, leads to progressive physical, psychological and social disabilities and dehabilitation.[2] The associated visible deformities and disabilities have contributed to the stigma and discrimination experienced by leprosy patients, even among those who have been cured.[3] Because of the stigma associated with the disease, patients sometimes delay seeking proper care until they develop physical deformities. The quality of life of such persons declines rapidly. Stigma toward persons affected by leprosy and their families has also adversely affected their quality of life due to its impact on their mobility, interpersonal relationships, marriage employment, leisure and social activities.[4]

In early days, leprosy patients used to be forced to leave their home and some of them were admitted to asylums or sanatoriums. Today, however, they remain within their families, although they are often looked down upon and may receive little or no support from their communities. Much of the stigma associated with leprosy stems from inadequate or incorrect knowledge about the disease and its current treatment.[5,6] Even after nearly two decades of excellent multi-drug therapy and remedies for reaction and ulcers, large segments of rural population seem ignorant or weakly motivated to seek early treatment.[7] In India, many leprosy rehabilitation centers are working for the physical, social and vocational rehabilitation of leprosy patients. Hence, the present study was conducted to throw light on the quality of life of leprosy patients, their knowledge, belief and attitude about leprosy disease as compared with community members.

Aims and Objectives

To assess the knowledge, attitude and belief about leprosy in leprosy patients compared with community members.

To find the perceived stigma among leprosy patients.

To evaluate the quality of life in leprosy patients compared to community members using World Health Organization Quality of life Assessment BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted in October-December 2009 at the Leprosy Rehabilitation Centre, Shantivan Nere, in Panvel taluka, District Raigad, where leprosy patients from all over Maharashtra came for diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation.

Data collection

On an average, 120 leprosy patients stay with their family at the center. The study was conducted on patients in the center and controls selected randomly from the surrounding area of Shantivan Nere, who were properly matched for age, sex and occupation.

About 50% of leprosy patients were selected randomly and their consent for the study was obtained. Patients with debilitating disease and psychiatric problems were excluded from the study. Thus, 51 cases were selected for the study. These leprosy patients were compared with 58 community members (controls). Individuals with reported history of leprosy or chronic disease were excluded from the controls.

Instrument

A pre-designed and pre-structured questionnaire was used to evaluate knowledge, attitude, belief and perceived stigma in leprosy patients and community members. The questionnaire was piloted and necessary changes were done beforehand. In addition to the questions that examined the socio-demographic characteristics and Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) of leprosy, the WHOQOL-BREF was used. This questionnaire was developed to evaluate QOL and contains 26 items divided into four domains: physical, psychological, social relationships and environmental.[8,9] Each item uses a 5-point response scale, with higher scores indicating a better QOL. The validity and reliability of the Bangla version of the WHOQOL-BREF has been previously confirmed.[10]

Interns were trained beforehand to conduct the interview for leprosy patients as well as controls.

Data analysis

WHOQOL-BREF total scores and physical, psychological, social relationships and environmental domain subscales were compared between patients and control with the help of SPSS.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic profile

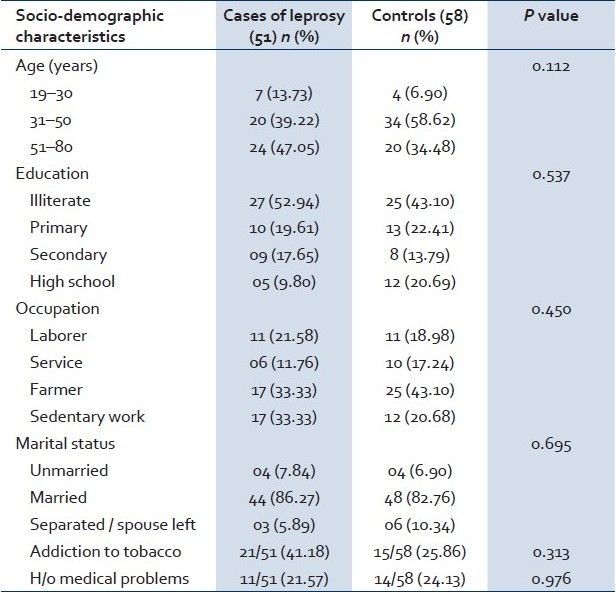

The socio-demographic profile of the leprosy patients and the community members in shown in Table 1. It is seen that age, education and marital status of both the leprosy patients and controls were comparable. Almost half of the study group and controls were illiterate. More than 80% of the population in both the study and control groups was married, suggesting that leprosy is not a deterrent for marriage.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of study subjects

Knowledge of leprosy

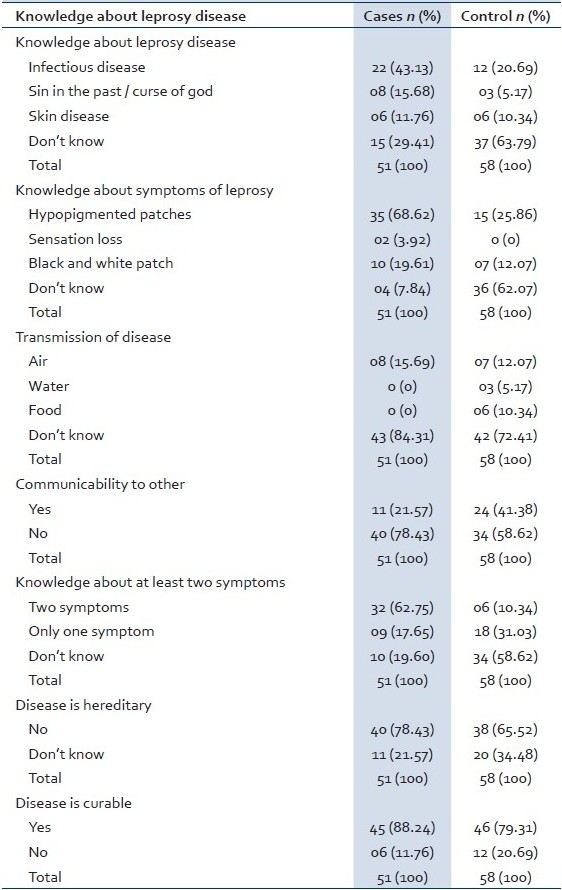

Table 2 compares the knowledge regarding leprosy among cases and controls. It is seen that 43.13% of cases were aware that leprosy is an infectious disease compared to 20.69% of the controls. 68.62% of cases were aware of hypopigmented patches being a symptom of leprosy, compared to 25.86% of controls. It was, however, seen that the knowledge regarding transmission of disease was poor in both the groups. 72.41% of the control group and 84.31% of cases did not know the mode of disease transmission.

Table 2.

Knowledge about leprosy as a disease among leprosy cases and controls

41.38% of the control group was aware that leprosy is a communicable disease, compared to the study group (21.57%). There was a high level of awareness about the fact that the disease is not hereditary (78.43% in the study group and 65.52% in the control group) and that the disease is curable (88.24% in the study group and 79.31% in the control group).

This probably indicates that the health education provided to the patients along with treatment has increased the knowledge and awareness of leprosy in the cases as compared to controls.

Attitude toward leprosy

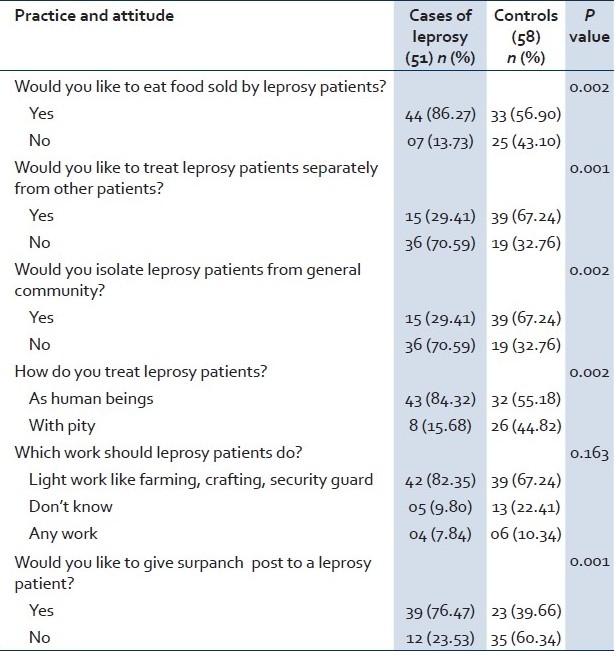

Table 3 shows that that among the control group, 43.10% of population said that they would not like food to be served by leprosy patients, compared to 13.73% in the study group. This was found to be statistically significant. As many as 67.24% in the control group said that either leprosy patients should be treated separately or isolated, which was also found to be statistically significant.

Table 3.

Attitude toward leprosy

60.34% of people in the control group were against the idea of a key post to be given to leprosy patients, against 23.53% in the study group, which was found to be statistically significant. Almost 82.35% in the study group and 67.24% in the control group agreed that the patients should be given light work.

Discrimination in leprosy patients

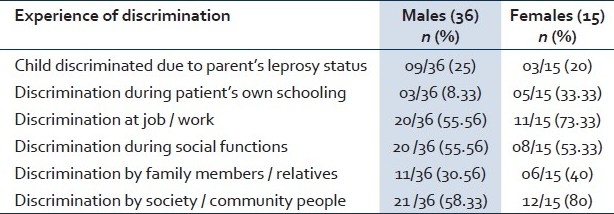

Table 4 shows that out of the 51 leprosy patients examined, it was seen that though both the sexes complained of being discriminated, the discrimination was much higher in female patients as compared to male patients. This may be due to a patriarchal society where the preference is for male sex.

Table 4.

Experience of discrimination in leprosy patients

WHOQOL-BREF of patients and community members

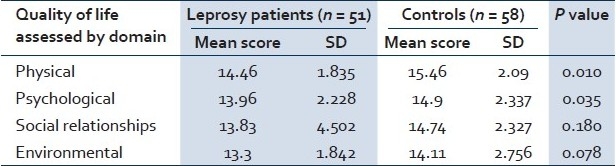

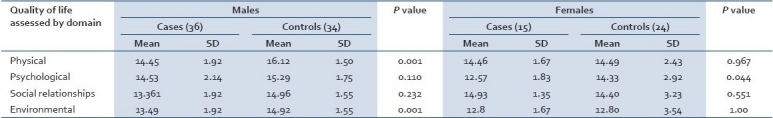

To compare total WHOQOL-BREF scores between two groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized. The mean QOL scores for cases and controls in each domain are indicated in [Tables 5 and 6]. Except in the social relationship and environmental domain, the mean scores for cases were significantly lower than those for control group in physical and psychological domains. The mean QOL scores for male cases were lower in each domain as compared to male control group and the difference was not significant except in the physical and environmental domains. The mean QOL scores for female cases were lower in each domain as compared to female control group and the difference was not significant except in the psychological domain. The mean QOL scores for females were significantly lower in psychological and environmental domain as compared to male cases.

Table 5.

Mean quality of life scores by domain

Table 6.

Quality of life assessed by domain in male and female

DISCUSSION

Leprosy can be seen as having psychological, socioeconomic and spiritual dimensions that progressively dehabilitate the affected persons who are not properly cared for. The emergence of multi-drug therapy has given rise to optimism about the prospects for eliminating the disease and preventing disability and dehabilitation.[11] Consequently, the degree of decline in the QOL needs to be reviewed and correlated with various socio-demographic and environmental factors, including the ones associated with health services.

The present study revealed that the overall the QOL of leprosy patients was lower in physical domain and psychological domain than the control group, but a significant difference was not found in social relationship and environmental domain. Our findings are consistent with the findings of the studies conducted in Tamil Nadu and Bangladesh.[12,13]

When male leprosy patients were compared with male controls, there was a significant difference in the physical domain, but no significant difference was found in other domains like psychological, social relationship and environment. This could be because the study was conducted in a leprosy rehabilitation center where patients are socially and vocationally rehabilitated. This may counter the effects of psychological and socio-environmental factors over the QOL of leprosy patients.

For females, WHOQOL-BREF mean scores of psychological domain were significantly lower in leprosy patients than in control group. There were no differences in both groups (cases and controls) with respect to other domain like physical, social relationship and environment. The lower scores for psychological domain may be due to the greater discrimination against female leprosy patients as compared to male patients by the society.

The above findings are contradictory to the findings of the studies conducted in Tamil Nadu and Bangladesh.[12,13] Lack of accurate knowledge about leprosy in the community could be an important factor in hindering leprosy elimination. The present study revealed that leprosy patients were more aware about the infectious nature of disease, symptoms, transmission, and curability than the control group. Our study findings are similar and consistent with the findings of various studies.[13–15]

In the present study it was found that more than half the population in the control group was of the opinion that leprosy patients should be treated separately and must be isolated. Thus, it is seen that there is still a negative attitude toward leprosy patients in the society. Similar results were obtained in a study conducted in Andhra Pradesh.[16]

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the Shantivan Leprosy Foundation, Nere, Panvel, for their cordial support while conducting the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joshi PL, Barkakaty BN, Thorat DM. Recent development in elimination of leprosy in India. Indian J Lepr. 2007;79:107–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joseph GA, Rao PS. Impact of Leprosy on quality of life. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:515–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsutsumi A, Izutsu T, Islam AM, Maksuda AN, Kato H, Wakai S. The quality of life and mental health and perceived stigma of leprosy patients in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2443–53. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong ML. Designing Programmes to address stigma in leprosy: Issues and challenges. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabil J. 2004;15:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.International leprosy Association. Report of the Technical Forum. Lepr Rev. 2002;73:58–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seventh report, WHO Technical Report series 847. Geneva: WHO; 1997. World Health Organization. Expert Committee on leprosy. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivasan H. Social sciences research and social action for better leprosy control: Papers and other documents presented at IAL National Workshop at Karigiri, 14-15 Mar 1991. Indian Association of Leprologists. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHOQOL-BREF instrumentation, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. World Health organization. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHOQOL: Measuring quality of life. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izutusu T, Tsutsumi A, Islam A, Matsuo Y, Yamada HS, Kurtika H, et al. Validity and reliability of the Bangla version of WHOQOl- BREF on an adolescent population in Bangladesh. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1783–9. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-1744-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leprosy beyond the year 2000. Lancet. 1997;350:1717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The WHOQOL Group. What quality of life? World Health Forum. 1996;17:354–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.John AS, Rao PS. Awareness and attitudes towards leprosy in urban slums of Kolkata, India. Indian J Lepr. 2009;81:135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barkataki P, Kumar S, Rao PS. Knowledge of and attitudes to leprosy among patients and community members. A comparative study in Uttar Pradesh, India. Lepr Rev. 2006;77:62–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nisar N, Khan IA, Qadri MH, Shah GN. Knowledge, attitude and practices about leprosy in a fishing community in Karachi, Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2007;23:936–40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raju MS, Kopparty SN. Impact of knowledge of leprosy on the attitude towards leprosy patients: A community study. Indian J Lepr. 1995;67:259–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]