Abstract

Trichotillomania is an impulse-control disorder. The underlying psychiatric comorbidity or functional impairment is well recognized by clinicians. Patients with trichotillomania pull their scalp hairs, resulting in damaged, distorted hair follicles, and broken hair shafts within the skin. The local irritation and inflammation resulting from reaction to the broken, impacted hair shafts and malaligned regrowing hair can lead to pseudofolliculitis, much the same as a patient who waxes or shaves her legs gets itchy papules of pseudofolliculitis. Pseudofolliculitis becomes an organic reason for scalp itch and discomfort, and contributes further to the vicious cycle of itch and scratching in trichotillomania. This phenomenon has not been well documented. Treatment of trichotillomania would be more effective if the pseudofolliculitis component is addressed. We describe a series of patients with trichotillomania and pseudofolliculitis. These patients improved after topical steroid therapy, topical or oral antibiotics. Hair regrowth was also visibly better, with patients reporting improvement of symptoms of itch. All these patients were not placed on antidepressants nor antipsychotics.

Keywords: Hair disorders, pseudofolliculitis, therapy, trichotillomania

INTRODUCTION

Trichotillomania is classified by the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostics and Statistics Manual for Mental Health Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)[1] as an impulse-control disorder with recurrent hair pulling and occurs with a prevalence of 0.6-1.6% if strict DSM-IV criteria are applied.[2]

Itch and inflammation as a consequence of damaged hair from plucking can lead to pseudofolliculitis.[3] This is often seen in women who shave or wax the hair of the legs, axillae and pubic region. We describe for the first time pseudofolliculitis occurring in trichotillomania. The pseudofolliculitis becomes an organic reason for scalp itch and discomfort, and contributes further to the vicious itch-scratch cycle in trichotillomania. We outline the clinical presentation of trichotillomania-associated pseudofolliculitis, the approach to diagnosis and the management of these individuals.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We report five patients with trichotillomania induced pseudofolliculitis at the National Skin Centre, Singapore over a period of 3 years (2007 to 2010). This study was reviewed and approved by the local ethics review board. We document the features, treatment, and clinical outcomes of these five patients.

RESULTS

Patient 1

A 7-year-old Chinese girl presented with two months’ duration of trichotillomania and intractable scalp itch arising from the site of the hairloss. She pulled and pressed her hair to relieve the itch. Clinical examination showed an area of hairloss consistent with trichotillomania, with an excoriation adjacent to a papule [Figure 1a]. She was advised not to pull her hair, and responded to betamethasone 0.1% scalp lotion, erythromycin 2% solution, and cetrimide shampoo to treat the pseudofolliculitis.

Figure 1.

(a) Excoriated scalp papules at the sites of non-scarring alopecia induced by trichotillomania (b) Distorted and inwardly curving hairs of pseudofolliculitis

Patient 2

This 13-year-old Chinese female complained of itch and hairloss for 6 months. Scalp papules, coiled and twisted ingrowing hairs associated with bizarre areas of hair loss were noted on closer examination [Figure 1b]. Apart from advice to cease pulling her hair, oral erythromycin, clobetasol scalp lotion, and selenium sulphide shampoo improved the scalp itch and lead to resolution of the papules one month later.

Patient 3

This 18-year-old Indian male with five years’ duration of hairloss, scalp itch and papules pulled his hair to relieve the tension of a stressful relationship with his grandmother. On examination, there were irregularly shaped areas of hair loss associated with follicular papules. After three months of treatment with betamethasone and clindamycin 1% solutions, there was decrease in scalp itch with good regrowth of hair at the vertex and left parietal regions [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

(a) Treatment of pseudofolliculitis with betamethasone and clindamycin lotion resulting in objective improvement of alopecia. Appearance at initial consultation (b) Appearance three months after treatment

Patient 4

An 18-year-old Malay female presented with hairloss for six months. Although she readily admitted to an urge to manipulate her hair when under stress from school work and habitually tugging her hair while studying, a complaint of itch was only elicited during her second consult when scalp papules were discovered at the sites of alopecia. The patient herself was unaware of the papules and did not associate them with the scalp itch. She fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for trichotillomania. A review at the National Skin Centre psychodermatology clinic was offered but she declined. Together with advice against hair pulling, doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 6 weeks lead to less scalp papules, decrease in scalp itch and improvement in hair regrowth.

Patient 5

This 46-year-old Malay woman was previously described with a variant of trichotillomania termed leucotrichotillomania.[4] This refers to the selective pulling of white hairs. She enlisted the help of family members and mirrors to assist her in plucking the unsightly white hairs. Hair pulling behaviour started 16 years prior when she developed white hairs after child birth, but became more problematic of late over the last 3 years when she developed more white hairs. The short, stubby regrowth of white hairs caused itch. Her pruritus was relieved by plucking the hairs and this lead to a vicious cycle of hair pulling. Large bizarre patchy areas of alopecia were noted over the vertex and bifrontal regions. Histology revealed trichomalacia with pigment casts, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of trichotillomania. She declined a psychiatric review. Betamethasone scalp lotion and coal tar shampoo relieved the scalp itch from the ingrown hairs, while hair dyeing helped to make the white hairs less visible and improve her compliance to advice against pulling her hair.

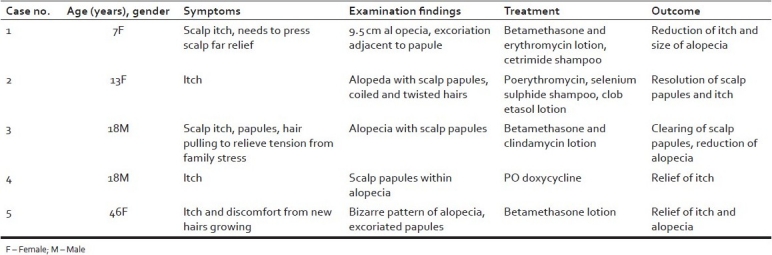

The clinical characteristics and outcomes of our patients is summarized in [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinical details of the case series

DISCUSSION

The psychiatric comorbidities of trichotillomania have been well documented.[2,5–7] These include obsessive compulsive disorder, depression, and anxiety. This is the first case series describing pseudofolliculitis associated with trichotillomania. We feel that this entity is under-recognised by clinicians.

As the affected patients in our series ranged in age from 7 to 46 years and spanned three different races, the true prevalence of pseudofolliculitis amongst patients with trichotillomania is likely significant.

Identifying features included the presence of scalp pruritus, papules, excoriations and in some cases, distorted and ingrown hairs. However, not all patients (Case 4) were forthcoming with their symptoms of itch; this same patient also did not realise she had scalp papules. If left untreated, patients can harbour symptoms for an extended period of time as Case 3 and 5 illustrate, with considerable pruritus and hairloss. It is noteworthy that these patients improved on a simple regimen of topical steroid, antipruritic shampoo, topical or oral antibiotics. None were placed on psychotropic medications or seen by a psychiatrist. However, patients were taught habit reversal techniques and counseled on stress management strategies by dermatologists in a centre with a psychodermatology unit.

The pathogenesis of trichotillomania is multifactorial and complex.[2,5,8] Patients with trichotillomania pull their hairs either due to a habit tic or an obsessive compulsive need to relieve a perceived or inorganic source of follicular itch. In certain cases, rubbing of the hair or trichoteiromania[9] may occur either in isolation or concurrently with trichotillomania. Pseudofolliculitis develops as a result of a foreign body reaction to the sharp ends of the new, ingrown and coiled hairs.[3] While it is unclear whether the inflammatory scalp papules preceded or followed from the hair pulling, we postulate that the inwardly curving, regrowing hairs from repeated pulling incite a local inflammatory reaction, culminating in a vicious cycle of itching, scratching, and pulling. Treating the pseudofolliculitis that is secondary to the trichotillomania or trichoteiromania would remove an additional source of organic scalp itch, thereby allowing patients to concentrate on behaviour modification techniques for treatment of the trichotillomania itself. Prospective studies are required to assess the prevalence, relapse rate, psychiatric comorbidities, and long term prognosis of this condition.

CONCLUSION

Trichotillomania-induced pseudofolliculitis is a newly described condition. Treatment of the pseudofolliculitis with topical steroids, oral, or topical antibiotics improves hair regrowth.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric; 1994. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Sullivan RL, Mansueto CS, Lerner EA, Miguel EC. Characterization of trichotillomania: A phenomenological model with clinical relevance to obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2000;23:587–604. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dilaimy M. Pseudofolliculitis of the legs. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:507–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JS. Successful treatment of ‘leucotrichotillomania’ by hair dyeing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e407–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh KH, McDougle CJ. Trichotillomania: Presentation, etiology, diagnosis, and therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:323–3. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen LJ, Stein DJ, Simeon D, Spadaccine E, Rosen J, Aronowitz B, et al. Clinical profile, comorbidity, and treatment history in 123 hair pullers: A survey study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56:319–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simeon D, Cohen LJ, Stein DJ, Schmeidler J, Spadaccini E, Hollander E. Co-morbid self-injurious behavior in 71 female hair pullers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:117–9. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199702000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamberlain SR, Menzies L, Sahakian BJ, Fineberg NA. Lifting the veil on trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:568–74. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freyschmidt-Paul P, Hoffmann R, Happle R. Trichoteiromania. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:369–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]