Abstract

Organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) are a public health concern due to their worldwide use and documented human exposures. Phosphorothioate OPs are metabolized by cytochrome P450s (P450s) through either a dearylation reaction to form an inactive metabolite, or through a desulfuration reaction to form an active oxon metabolite, which is a potent cholinesterase inhibitor. This study investigated the rate of desulfuration (activation) and dearylation (detoxification) of methyl parathion and diazinon in human liver microsomes. In addition, recombinant human P450s were used to determine the P450-specific kinetic parameters (Km and Vmax) for each compound for future use in refining human physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) models of OP exposure. The primary enzymes involved in bioactivation of methyl parathion were CYP2B6 (Km = 1.25 μM; Vmax = 9.78 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1), CYP2C19 (Km = 1.03 μM; Vmax = 4.67 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1), and CYP1A2 (Km = 1.96 μM; Vmax = 5.14 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1), and the bioactivation of diazinon was mediated primarily by CYP1A1 (Km = 3.05 μM; Vmax = 2.35 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1), CYP2C19 (Km = 7.74 μM; Vmax = 4.14 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1), and CYP2B6 (Km = 14.83 μM; Vmax = 5.44 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1). P450-mediated detoxification of methyl parathion only occurred to a limited extent with CYP1A2 (Km = 16.8 μM; Vmax = 1.38 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1) and 3A4 (Km = 104 μM; Vmax = 5.15 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1), whereas the major enzyme involved in diazinon detoxification was CYP2C19 (Km = 5.04 μM; Vmax = 5.58 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1). The OP- and P450-specific kinetic values will be helpful for future use in refining human PBPK/PD models of OP exposure.

Introduction

Organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) continue to be a human health concern due to their worldwide use, documented human exposures, and neurotoxic potential (Jaga and Dharmani, 2006; Farahat et al., 2010, 2011). Phosphorothioate OPs require metabolic activation to significantly inhibit acetylcholinesterase, which is thought to mediate the acute toxicity of these compounds (Myers et al., 1952; Sultatos, 1994). Metabolism studies for a variety of OPs have clearly indicated that their bioactivation is attributable to cytochrome P450 (P450)-mediated metabolism (Buratti et al., 2003; Sams et al., 2004; Foxenberg et al., 2007). Upon entry into the body, phosphorothioate OPs undergo a P450-mediated desulfuration reaction to form an active, highly toxic oxon intermediate metabolite that is responsible for the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase, and carboxylesterase (Ma and Chambers, 1994). Detoxification of the active oxon metabolite occurs by enzymatic hydrolysis mediated by A-esterases such as paraoxonase 1 (Pond et al., 1998). The parent OP compound can also undergo a P450-mediated dearylation reaction to form detoxified metabolites (Ma and Chambers, 1994). The balance between activation and detoxification of OPs determines their relative risk to humans.

Methyl parathion and diazinon are currently used in agriculture. Diazinon was once widely used in the United States for residential and garden applications, but since 2004 its use has been restricted to agriculture applications. Methyl paraoxon and diazoxon are the activated forms of methyl parathion and diazinon, respectively, whereas p-nitrophenol (PNP) and pyrimidinol (IMP) represent the detoxified metabolites.

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) models allow researchers to predict the kinetics of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of OPs and also to assess the risks associated with their exposure using biochemical and physiological parameters generated from in vitro and in vivo studies in animals and in man (Knaak et al., 2004). Previously published PBPK/PD models have used kinetic parameters for OP metabolism largely generated from nonhuman studies. These models tend to be unstable, nonreproducible, and under-representative of interindividual variability when applied to humans (Knaak et al., 2004). To improve on existing models, there is a need to generate kinetic constants for human-derived enzymes involved in metabolism of specific OPs. The use of species-specific kinetic parameter values, such as enzyme Km and Vmax values, for the metabolism of OPs by specific recombinant human P450s together with P450-specific content (pmol of P450/mg microsomal protein) would allow for more accurate adjustments of model parameters for age, sex, genetic polymorphisms, and other factors that may influence P450 content and activity and, therefore, OP metabolism and effects (Foxenberg et al., 2011).

There is currently a lack of human P450-specific kinetic data for the metabolism of methyl parathion and diazinon. To date, no studies have identified the major human P450s involved in methyl parathion metabolism. Studies that have assessed the human P450-specific metabolism of diazinon have used relatively few substrate concentrations, thus preventing the determination of kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax, and Clint) (Kappers et al., 2001; Sams et al., 2004; Mutch and Williams, 2006). The goal of the current study was to identify the human P450s involved in methyl parathion and diazinon metabolism, as well as their respective Km and Vmax values for activation and detoxification. These human P450-specific kinetic parameters can then be used in P450-based/age-specific PBPK/PD models for assessing the risk of OP exposure in man.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

Methyl parathion (CAS no. 298-00-0), diazinon (CAS 333-41-5), methyl paraoxon (CAS 950-35-6), diazoxon (CAS 962-58-3), and IMP (CAS 2814-20-2) were purchased from ChemService, Inc. (West Chester, PA); p-nitrophenol (CAS 100-02-7) and tetraisopropyl pyrophosphoramide (iso-OMPA; CAS 513-00-8) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO); MgCl2 and EDTA were purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker, Inc. (Phillipsburg, NJ) and were of at least reagent grade quality. Methanol and acetonitrile (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ) were high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade. Pooled human liver microsomes (HLM) and recombinant human P450s (CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7) were purchased from Gentest (BD Biosciences Discovery Labware, Bedford, MA). Recombinant P450 enzymes were prepared from a baculovirus-infected insect cell system containing oxidoreductase.

Experimental Conditions.

OP stock solutions were prepared in 50% methanol/water and stored at −20°C when not in use. Incubations with either HLM (0.5–1.0 mg protein/ml) or recombinant P450s (0.03–0.06 nmol P450/0.5 ml) were carried out in buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 50 μM iso-OMPA, pH 7.4) at 37°C in a final volume of 0.25 ml (methyl parathion) or 0.5 ml (diazinon). Reactions were initiated with the addition of 1 mM NADPH and incubated for 2 min at 37°C. EDTA and iso-OMPA were included to inhibit A-esterases and B-esterases, respectively (Reiner et al., 1993). The reaction was quenched with 1 volume of ice-cold methanol containing 0.1% phosphoric acid, centrifuged, and the supernatant was transferred to HPLC vials for analysis.

Metabolite Detection.

OPs and their respective metabolites were analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC (C18, 5 μM particle size, 25 cm × 4.6 mm ID; Supelco, St. Louis, MO) using a Hewitt-Packard (Palo Alto, CA) model 1100 HPLC with model 1046A diode-array detector. Methanol (solvent A), 94.8% water/5% methanol/0.2% phosphoric acid (solvent B), acetonitrile (solvent C), and 94.9% water/5% methanol/0.1% phosphoric acid (solvent D) were used for gradient elution. For methyl parathion, the mobile phase consisted of the following: 0 to 6 min, 30% solvent A/70% solvent B; 6 to 20 min, linear gradient to 90% solvent A/10% solvent B; 20 to 23 min, 90% solvent A/10% solvent B; 23 to 24 min, linear gradient to 100% solvent A; 24 to 30 min, 100% solvent A; 30 to 33 min, linear gradient to 30% solvent A/70% solvent B. For diazinon, the mobile phase consisted of the following: 0 to 5 min, 100% solvent D; 5 to 13 min, linear gradient to 40% solvent C/60% solvent D; 13 to 15 min, linear gradient to 45% solvent C/55% solvent D; 15 to 23 min, linear gradient to 100% solvent C; 23 to 28 min, 100% solvent C; 28 to 32 min, linear gradient to 100% D. The flow rate was 1 ml/min and the injection volume was 50 μl. Methyl parathion and methyl paraoxon were detected at 275 nm, PNP was detected as 320 nm, diazinon and diazoxon were detected at 245 nm, and IMP was detected at 230 nm. The retention times for methyl parathion, methyl paraoxon, and PNP were 20.4, 15.4, and 13.7 min, respectively. The retention times for diazinon, diazoxon, and IMP were 24.6, 20.0, and 11.6 min, respectively.

Data Analysis.

The kinetic values, Km and Vmax, were determined by nonlinear regression analysis (Enzyme Kinetics Module of SigmaPlot, version 11; Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA) of hyperbolic plots (i.e., velocity versus [S]) obeying Michaelis-Menten kinetics. OP parent compound concentration (μM) was set as the independent variable, whereas rate of product formation (pmol/mg protein/min for HLM or pmol/nmol P450/min for recombinant P450s) was the dependent variable.

Results

Pooled HLM were used to determine kinetic values (Km and Vmax) for metabolism of methyl parathion and diazinon. For methyl parathion, the Km and Vmax values were 0.99 μM and 0.11 nmol · min−1 · mg protein−1 for PNP formation and 66.8 μM and 1.84 nmol · min−1 · mg protein−1 for methyl paraoxon formation. For diazinon, the Km and Vmax values were 31 μM and 1.18 nmol · min−1 · mg protein−1 for IMP formation and 30 μM and 0.73 nmol · min−1 · mg protein−1 for diazoxon formation.

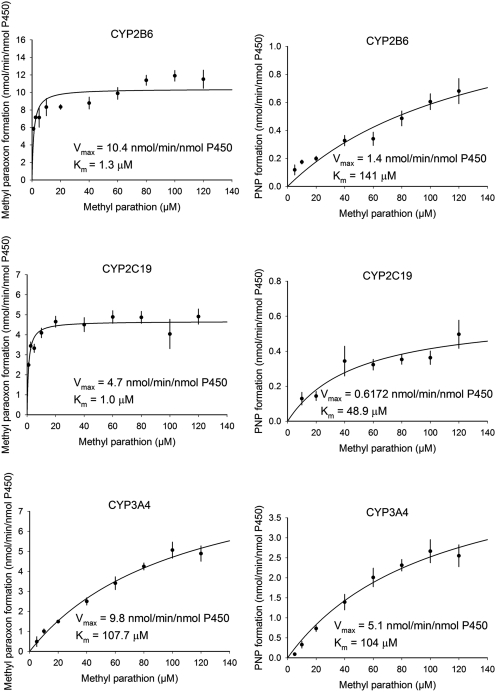

Recombinant human P450s were used to identify the human P450s responsible for methyl parathion and diazinon metabolism. The Michaelis-Menten plots for the metabolism of methyl parathion by P450s CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 are shown in Fig. 1, whereas Table 1 shows the kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax, Clint) for each human P450 capable of metabolizing methyl parathion and diazinon. The desulfuration (activation) of methyl parathion to methyl paraoxon was catalyzed primarily by CYP2B6 > CYP2C19 > CYP1A2, whereas the desulfuration (activation) of diazinon to diazoxon was catalyzed by CYP1A1 > CYP2C19 > CYP2B6 (Table 1). CYP3A4 had among the largest Vmax values for desulfuration of methyl parathion (Vmax = 9.78 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1) and diazinon (Vmax = 5.44 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1), but at the same time it also had the highest Km value (methyl parathion = 107 μM; diazinon = 28.7 μM) among the P450s tested (Table 1). The Km values for desulfuration of methyl parathion by CYP2B6 (Km = 1.25 μM) and CYP2C19 (Km = 1.03 μM) were the lowest among the P450s involved in methyl parathion metabolism (Table 1). For diazinon, the lowest Km values for desulfuration were for CYP1A1 (Km = 3.05 μM) and CYP2C19 (Km = 7.74 μM) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Kinetic plots for methyl parathion metabolism by recombinant human CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4. Values represent the mean ± S.E.M. of three (CYP3A4) or four (CYP2B6 and CYP2C19) determinants.

TABLE 1.

Methyl parathion and diazinon metabolism by recombinant human P450s

| Cytochrome P450 | Methyl Paraoxon Formation |

PNP Formation |

Diazoxon Formation |

IMP Formation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km | Vmax | Clint | Km | Vmax | Clint | Km | Vmax | Clint | Km | Vmax | Clint | |

| μM | nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1 | ml/(nmol P450 · min) | μM | nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1 | ml/(nmol P450 · min) | μM | nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1 | ml/(nmol P450 · min) | μM | nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1 | ml/(nmol P450 · min) | |

| CYP1A1a | 13.5 ± 14.22 | 1.51 ± 0.40 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| CYP1A2a | 1.96 ± 0.64 | 5.14 ± 0.27 | 2.62 | 16.8 ± 6.07 | 1.38 ± 0.14 | 0.08 | ||||||

| CYP3A4a | 107 ± 29.4 | 9.78 ± 1.52 | 0.09 | 104 ± 39.2 | 5.15 ± 1.09 | 0.05 | ||||||

| CYP2B6b | 1.25 ± 0.32 | 10.39 ± 0.37 | 8.30 | 141 ± 72.3 | 1.42 ± 0.45 | 0.01 | ||||||

| CYP2C19b | 1.03 ± 0.25 | 4.67 ± 0.15 | 4.51 | 48.9 ± 26.6 | 0.62 ± 0.14 | 0.01 | ||||||

| CYP2D6a | 50.3 ± 8.36 | 5.82 ± 0.41 | 0.12 | |||||||||

| CYP2E1c | 54.4 | 2.79 | 0.05 | |||||||||

| CYP1A1b | 3.05 ± 1.08 | 2.35 ± 0.19 | 0.771 | 29.9 ± 30.4 | 1.77 ± 1.00 | 0.059 | ||||||

| CYP1A2b | 23.8 ± 11.1 | 2.66 ± 0.37 | 0.112 | |||||||||

| CYP3A4b | 28.7 ± 27.3 | 5.44 ± 1.43 | 0.19 | 43.7 ± 10.4 | 10.00 ± 0.93 | 0.229 | ||||||

| CYP2B6b | 14.83 ± 7.13 | 5.44 ± 0.58 | 0.366 | 13.94 ± 3.37 | 2.60 ± 0.15 | 0.186 | ||||||

| CYP2C19b | 7.74 ± 11.45 | 4.14 ± 0.84 | 0.535 | 5.04 ± 0.94 | 5.58 ± 0.19 | 1.12 | ||||||

Values represent the mean ± S.E.M. of an = 3 or bn = 4 determinants or cthe mean of n = 2 determinants.

P450-mediated dearylation (detoxification) of methyl parathion only occurred to a limited extent with CYP1A2 [Clint = 0.08 ml/(nmol P450 · min)] and CYP3A4 [Clint = 0.05 ml/(nmol P450 · min)], whereas CYP2C19 was the major enzyme involved in diazinon detoxification (Table 1). The Km and Vmax for CYP2C19 dearylation of diazinon was 5.0 μM and 5.58 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1 (Table 1).

Discussion

Hepatic microsomes contain many forms of P450s, making them ideal for assessing combinatorial P450-mediated metabolism of OPs. Whereas pooled HLM are useful to address metabolic capacity in the general sense, they do not provide information on the individual capacity of P450s to metabolize an OP. To better address the limitations of using pooled HLM, metabolism studies were conducted with 10 recombinant human P450s to identify the human P450s responsible for methyl parathion and diazinon metabolism. CYP3A4 had among the largest Vmax values for desulfuration of methyl parathion and diazinon, but at the same time it also had the highest Km value among the P450s tested, which minimizes the role of CYP3A4 in metabolism at lower OP exposures. This observation is consistent with previous studies in which CYP3A4 was suggested to be important in the metabolism of OPs at higher concentrations (Buratti et al., 2003). CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 had the lowest Km values for desulfuration (activation) of methyl parathion, supporting the major role these P450s play in metabolism at low-level real-world exposures. For diazinon, CYP1A1 and CYP2C19 had the lowest Km values for desulfuration. The identification of CYP2C19 as a key enzyme involved in diazinon activation expands upon a previous study that reported CYP2C19 to have a low Km for diazinon metabolism (Kappers et al., 2001).

CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 have also been identified as the major P450s involved in the metabolism of other OPs, such as chlorpyrifos and parathion (Foxenberg et al., 2007). With regard to the metabolism of chlorpyrifos to its active oxon metabolite (chlorpyrifos-oxon), CYP2B6 is the most active P450 enzyme as shown by its low Km (0.81 μM), high Vmax (12.54 nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1), and high Clint [15.56 ml/(nmol P450 · min)], thus demonstrating the importance of CYP2B6 in chlorpyrifos activation (Foxenberg et al., 2007). In contrast, CYP2C19 has the highest Clint for the metabolism of chlorpyrifos to its detoxified metabolite, 3,4,5-trichlorpyrindinol, and thus plays an important role in chlorpyrifos detoxification. Similar to methyl parathion and diazinon metabolism, CYP3A4 displays a high Vmax for chlorpyrifos and parathion metabolism (Foxenberg et al., 2007); however, CYP3A4 also has a relatively high Km for these OPs, which minimizes its role at lower OP concentrations.

When assessing the contribution of a P450 isoform to the total hepatic metabolism of an OP, it is also important to consider the relative P450 abundance of each P450 isoform within the liver. Although CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 are more catalytically active (as represented by Clint) than CYP3A4 toward methyl parathion and diazinon, their hepatic content is approximately eight to nine times lower than CYP3A4 content (Yeo et al., 2004), and thus CYP3A4 may become important in overall hepatic metabolism due to its sheer abundance, even if its activity is lower than other P450s. The tissue distribution of P450s is also important when assessing OP metabolism. CYP2B6, the most active P450 involved in the bioactivation of methyl parathion and other OPs, is also located in most regions of the human brain (Gervot et al., 1999), suggesting that brain metabolism of OPs may be important when determining toxicity. A small amount of oxon formed in the brain may have a greater impact on systemic toxicity than the greater amount formed at the liver, which may not reach the brain. Albores et al. (2001) showed that CYP2B mediated the activation of methyl parathion in rat brain extracts, thereby further highlighting the significance of the CYP2B family of enzymes in OP metabolism.

The very limited dearylation (detoxification) of methyl parathion is markedly different from the metabolism of other OPs that show similar efficiencies for desulfuration and dearylation (Sams et al., 2004; Foxenberg et al., 2007). Anderson et al. (1992) assessed the metabolism of methyl parathion by subcellular fractions of isolated rat hepatocytes and reported a greater production of methyl paraoxon than PNP, which agrees with results obtained in the current study. However, Zhang and Sultatos (1991) reported that metabolism of methyl parathion by rat livers perfused in situ results in more PNP formation than methyl paraoxon. With regard to diazinon metabolism, P450s were able to mediate desulfuration and dearylation. The main P450 involved in diazinon metabolism, CYP2C19, demonstrated higher activity toward the formation of the detoxified metabolite compared with the bioactive metabolite, which is in agreement with previous reports (Sams et al., 2004; Mutch and Williams, 2006).

Some human PBPK/PD models for OP exposure currently use kinetic data acquired from rat liver microsomes, which does not reflect human enzymes (Poet et al., 2004). Recent work has shown how these PBPK/PD models can be converted from a rat microsome metabolism model to a human P450-specific metabolism model (Foxenberg et al., 2011). The P450-specific Vmax values (nmol · min−1 · nmol P450−1) obtained in the present study can be converted to in vivo values (μM · h−1 · kg−1 b.wt.) by multiplying the in vitro values by time (minutes per hour), P450 content (nmol/mg microsomal protein), microsomal protein (mg/g liver), and liver weight (g liver/kg b.wt.), and then dividing the resultant by 1.0E3. Inclusion of P450-specific kinetics into a human PBPK/PD model allows differences in human hepatic P450s to be accounted for. In addition to being the active P450s in methyl parathion and diazinon metabolism, substantial interindividual variability exists in CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 hepatic content. Human hepatic expression levels of CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 can vary by 100-fold and 20-fold, respectively (Ekins et al., 1998; Koukouritaki et al., 2004). In addition, both CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 contain polymorphisms capable of affecting enzymatic activity (Zanger et al., 2008). By having a PBPK/PD model that uses P450-specific parameters, interindividual differences in P450s can more accurately be accounted for, which will result in more accurate models for predicting effects from specific OP exposures.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Grant ES016308-02S] through a Research Supplement to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research (to C.A.E.); and the Environmental Protection Agency Science to Achieve Results [Grant R-83068301].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://dmd.aspetjournals.org.

- OPs

- organophosphorus pesticides

- P450

- cytochrome P450

- PNP

- p-nitrophenol

- IMP

- pyrimidinol

- PBPK/PD

- physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic

- Clint

- intrinsic clearance

- CAS

- Chemical Abstract Service

- iso-OMPA

- tetraisopropyl pyrophosphoramide

- HLM

- human liver microsomes

- HPLC

- high-performance liquid chromatography.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Ellison, Tian, Knaak, Kostyniak, and Olson.

Conducted experiments: Ellison and Tian.

Performed data analysis: Ellison and Tian.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Ellison, Tian, Knaak, Kostyniak, and Olson.

References

- Albores A, Ortega-Mantilla G, Sierra-Santoyo A, Cebrián ME, Muñoz-Sánchez JL, Calderón-Salinas JV, Manno M. (2001) Cytochrome P450 2B (CYP2B)-mediated activation of methyl-parathion in rat brain extracts. Toxicol Lett 124:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson PN, Eaton DL, Murphy SD. (1992) Comparative metabolism of methyl parathion in intact and subcellular fractions of isolated rat hepatocytes. Fundam Appl Toxicol 18:221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratti FM, Volpe MT, Meneguz A, Vittozzi L, Testai E. (2003) CYP-specific bioactivation of four organophosphorothioate pesticides by human liver microsomes. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 186:143–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekins S, Vandenbranden M, Ring BJ, Gillespie JS, Yang TJ, Gelboin HV, Wrighton SA. (1998) Further characterization of the expression in liver and catalytic activity of CYP2B6. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 286:1253–1259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farahat FM, Ellison CA, Bonner MR, McGarrigle BP, Crane AL, Fenske RA, Lasarev MR, Rohlman DS, Anger WK, Lein PJ, et al. (2011) Biomarkers of chlorpyrifos exposure and effect in Egyptian cotton field workers. Environ Health Perspect 119:801–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farahat FM, Fenske RA, Olson JR, Galvin K, Bonner MR, Rohlman DS, Farahat TM, Lein PJ, Anger WK. (2010) Chlorpyrifos exposures in Egyptian cotton field workers. Neurotoxicology 31:297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxenberg RJ, Ellison CA, Knaak JB, Ma C, Olson JR. (2011) Cytochrome P450-specific human PBPK/PD models for the organophosphorus pesticides: chlorpyrifos and parathion. Toxicology 285:57–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxenberg RJ, McGarrigle BP, Knaak JB, Kostyniak PJ, Olson JR. (2007) Human hepatic cytochrome P450-specific metabolism of parathion and chlorpyrifos. Drug Metab Dispos 35:189–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervot L, Rochat B, Gautier JC, Bohnenstengel F, Kroemer H, de Berardinis V, Martin H, Beaune P, de Waziers I. (1999) Human CYP2B6: expression, inducibility and catalytic activities. Pharmacogenetics 9:295–306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaga K, Dharmani C. (2006) Methyl parathion: an organophosphate insecticide not quite forgotten. Rev Environ Health 21:57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappers WA, Edwards RJ, Murray S, Boobis AR. (2001) Diazinon is activated by CYP2C19 in human liver. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 177:68–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaak JB, Dary CC, Power F, Thompson CB, Blancato JN. (2004) Physicochemical and biological data for the development of predictive organophosphorus pesticide QSARs and PBPK/PD models for human risk assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol 34:143–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukouritaki SB, Manro JR, Marsh SA, Stevens JC, Rettie AE, McCarver DG, Hines RN. (2004) Developmental expression of human hepatic CYP2C9 and CYP2C19. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 308:965–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Chambers JE. (1994) Kinetic parameters of desulfuration and dearylation of parathion and chlorpyrifos by rat liver microsomes. Food Chem Toxicol 32:763–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutch E, Williams FM. (2006) Diazinon, chlorpyrifos and parathion are metabolised by multiple cytochromes P450 in human liver. Toxicology 224:22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers DK, Mendel B, Gersmann HR, Ketelaar JA. (1952) Oxidation of thiophosphate insecticides in the rat. Nature 170:805–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poet TS, Kousba AA, Dennison SL, Timchalk C. (2004) Physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model for the organophosphorus pesticide diazinon. Neurotoxicology 25:1013–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond AL, Chambers HW, Coyne CP, Chambers JE. (1998) Purification of two rat hepatic proteins with A-esterase activity toward chlorpyrifos-oxon and paraoxon. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 286:1404–1411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner E, Pavković E, Radić Z, Simeon V. (1993) Differentiation of esterases reacting with organophosphorus compounds. Chem Biol Interact 87:77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sams C, Cocker J, Lennard MS. (2004) Biotransformation of chlorpyrifos and diazinon by human liver microsomes and recombinant human cytochrome P450s (CYP). Xenobiotica 34:861–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultatos LG. (1994) Mammalian toxicology of organophosphorus pesticides. J Toxicol Environ Health 43:271–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo KR, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Tucker GT. (2004) Abundance of cytochromes P450 in human liver: a meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 57:687–688 [Google Scholar]

- Zanger UM, Turpeinen M, Klein K, Schwab M. (2008) Functional pharmacogenetics/genomics of human cytochromes P450 involved in drug biotransformation. Anal Bioanal Chem 392:1093–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HX, Sultatos LG. (1991) Biotransformation of the organophosphorus insecticides parathion and methyl parathion in male and female rat livers perfused in situ. Drug Metab Dispos 19:473–477 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]