Abstract

We analyzed rest tremor, one of the etiologically most elusive hallmarks of Parkinson disease (PD), in 12 consecutive PD patients during a specific task activating the locus coeruleus (LC) to investigate a putative role of noradrenaline (NA) in tremor generation and suppression. Clinical diagnosis was confirmed in all subjects by reduced dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT) binding values investigated by single photon computed tomography imaging (SPECT) with [123I] N-ω-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) tropane (FP-CIT). The intensity of tremor (i.e., the power of Electromyography [EMG] signals), but not its frequency, significantly increased during the task. In six subjects, tremor appeared selectively during the task. In a second part of the study, we retrospectively reviewed SPECT with FP-CIT data and confirmed the lack of correlation between dopaminergic loss and tremor by comparing DAT binding values of 82 PD subjects with bilateral tremor (n = 27), unilateral tremor (n = 22), and no tremor (n = 33). This study suggests a role of the LC in Parkinson tremor.

Keywords: Parkinson disease, tremor, locus coeruleus, noradrenaline

Introduction

Tremor in Parkinson disease (PD) is characterized by 4–6 Hz activity at rest in the limbs with distal predominance. Despite its clinical importance and the burden of morbidity associated with it, the etiology of tremor is unknown, and its medical treatment commonly ineffective.

The tremor in PD is remarkable for several features: (1) it is neither a consistent nor a homogeneous feature across patients or within an individual patient's disease course; (2) it may diminish in the end-stage of PD; (3) it occurs predominantly at rest and is reduced or disappears by action; (4) it increases in amplitude or can be triggered by maneuvers such as walking or psychological states as anxiety or stress (specific tasks, like simple arithmetic calculation, may induce stress-related tremor) (Deuschl et al., 1998); (5) it is not present during sleep; (6) it may be the predominant or the only clinical sign for years before the appearance of akinesia (Brooks et al., 1992); and (7) it poorly correlates with the nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits (Isaias et al., 2007).

Although there is converging evidence of independent oscillating circuits within a widespread “tremor-generating network” (Mure et al., 2011), there is no conclusive explanation for the onset of tremor in what it is fundamentally a hypokinetic movement disorder.

Our hypothesis is that the locus coeruleus (LC) is involved in the generation of tremor in PD. Preliminary evidence of a role of adrenaline and noradrenaline (NA) in parkinsonian tremor emerged from studies published in the 1960s and 1980s (Constas, 1962; Colpaert, 1987; Wilbur et al., 1988).

In this study we applied a specific and selective task activating the LC (Raizada and Poldrack, 2008), the main source of NA in the brain, while recording tremor in 12 consecutive subjects with PD.

In a second part of the study, we confirmed retrospectively, in a large and homogeneous cohort of PD subjects with and without tremor, the lack of correlation between tremor and dopaminergic innervation loss, investigated by means of single photon computed tomography imaging (SPECT) with [123I] Nω-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) tropane (FP-CIT) (Isaias et al., 2007).

Materials and methods

Patients and clinical assessment

The diagnosis of PD was made in all subjects according to the UK Parkinson Disease Brain Bank criteria and patients were evaluated by means of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale motor part (UPDRS-III). Two additional UPDRS subscores (i.e., a tremor subscore and an akinetic-rigid (AK) subscore) were also calculated (Isaias et al., 2007). L-Dopa Equivalent Daily Doses (LEDDs) were recorded as follows: 100 mg levodopa = 1.5 mg pramipexole = 6 mg ropinirole.

Clinical inclusion criteria were: (1) UPDRS part I and IV of 0; (2) Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stage of 1 or 2 in drugs-off state at the time of SPECT (i.e., after overnight withdrawal of specific drugs for PD; no patient was taking long-acting dopaminergic drugs); (3) absence of any sign indicative for atypical parkinsonism (e.g., gaze abnormalities, autonomic dysfunction, and significant psychiatric disturbances) over a follow-up time of at least three years after symptoms onset; (4) positive clinical improvement at UPDRS after L-Dopa intake (i.e., >30% from drug-off state) at some point during the three years of follow-up; (5) a normal Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) (no sign of white matter lesion or atrophy).

Additional inclusion criteria for the 12 consecutive patients who took part to the prospective study were: (1) no other disease other than PD; (2) no therapy change for the past six months prior to the study; only patients with L-Dopa or dopamine agonist were recruited and the uptake of any drugs affecting the noradrenergic system (including, β-blockers, MAO-B inhibitors, etc.,) was ruled out; (3) no cognitive decline as well as no deficit in visual attention. All subjects had normal scores at the Mini-Mental State examination, the Clock Drawing Test, the Frontal Assessment Battery, the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; the Digit Span Test, and the Attentive Matrices Test. Depression was also ruled out by means of the Beck Depression Inventory.

Fifteen healthy controls (four males, 11 female; 63 years on average ±9 SD; range: 51–74 years) were prospectively enrolled for comparisons of FP-CIT uptake. Healthy controls were recruited from the general population (relatives of patients were excluded) and, at the time of the study, did not suffer from any disease and were not taking any medication.

The Local Ethics Committee approved the study and all subjects gave their informed consent.

Imaging

Dopamine-transporter (DAT) values were measured by means of SPECT with [123I] FP-CIT.

SPECT data acquisition and reconstruction has been described in details elsewhere (Isaias et al., 2010). In brief, intravenous administration of 110–140 MBq of FP-CIT (DaTSCAN, GE-Healthcare, UK) was performed 30–40 min after thyroid blockade (10–15 mg of Lugol oral solution) in subjects with PD subsequently overnight withdrawal of dopaminergic therapy and in healthy controls. Brain SPECT was performed three hours later by means of a dedicated triple detector gamma-camera (Prism 3000, Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) equipped with low-energy ultra-high resolution fan beam collimators (four subsets of acquisitions, matrix size 128 × 128, radius of rotation 12.9–13.9 cm, continuous rotation, angular sampling: 3 degree, duration: 28 min). Brain sections were reconstructed with an iterative algorithm Ordered Subsets Expectation Maximization (OSEM, four iterations and 15 subsets) and then processed by 3D filtering (Butterworth, order 5, cut-off 0.31 pixel-1) and attenuation correction (Chang method, factor 0.12).

FP-CIT uptake values for the caudate nucleus and putamen of both PD patients and healthy controls were calculated according to Basal Ganglia Matching Tool (Calvini et al., 2007). The FP-CIT uptake values in other brain regions were obtained with the creation, in the shapes menu of WFU Pick Atlas Tool, of specific volumes of interest (VOIs).

Contralateral refers to the side opposite to tremor or to the most affected side. For healthy controls we referred to the right side as ipsilateral (Isaias et al., 2007).

Audio-Visual task and experimental design

We used the task of audio-visual simultaneity detection (A-V, Raizada and Poldrack, 2008) in which subjects were presented with a flashed white disc and a burst of noise, their task being to decide whether the visual and the auditory stimuli were perceived, simultaneously or apart. A total of 50 visual and auditory stimuli were presented, 10–15 of them, in random order, delivered apart. The stimulus onset asynchrony between the visual and the auditory stimuli was set at 200 ms (A-V200), 100 ms (A-V100) or 0 ms (A-Vnull) in three separate trials. The A-V200 task demonstrated to specifically activate the LC-NA system. The A-V100 and the A-Vnull task did not appear to elicit a brainstem response and served as control tasks (Raizada and Poldrack, 2008). Inter-stimuli time (i.e., the time between a paired audio-visual stimulus and the following one) ranged randomly between 2.5 and 7 s. Each task was interpolated between a pre- (90 s) and a post-task period (up to epoch completion), with no audio-visual input. Trials were randomized for all patients. At the beginning of the experimental session, tremor activity was recorded for 60 s at rest and with no audio-visual input.

Recordings

Muscle activity was registered with surface Electromyography (EMG) electrodes placed on the extensor digitorum communis (EDC), the flexor digitorum communis (FDC), and the opponens pollicis (OP) muscles, bilaterally. To include only EMG bursting activity, the EMG was high-pass filtered off-line at 60 Hz and rectified (Timmermann et al., 2003). Recordings were performed during rest and during the audio-visual task while the subjects relaxed their arm and hand muscles. The examination was performed at the same day-time (10:00 h) for all patients. Patients were asked not to drink alcoholic, caffeine, or tea from the evening before the examination and they were off any medication in the last three days before the task. The examination was performed in a quiet room after allowing enough time for the patients to become familiar with the surroundings.

General statistical analysis

Tremor frequency and intensity were compared by use of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for matched pairs. A pair was the same individual but at a different time during the task (e.g., pre-task vs. task). Student's t-test was applied to compare DAT binding values among patient sub-groups and healthy controls. Statistical analyses were performed with the JMP statistical package, version 8.0.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographic and clinical features are listed in Table 1A for all subjects with PD and further detailed in Table 1B for the 12 patients who performed the audio-visual tasks.

Table 1A.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the 82 subjects with PD (A).

| Bilateral tremor (n = 27; 21 M) | On-side tremor (n = 22; 16 M) | No tremor (n = 33; 22 M) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset (years) | 54 ± 11 | 58 ± 8 | 55 ± 8 |

| Disease duration (years) | 8 ± 5 | 5 ± 3 | 7 ± 5 |

| UPDRS-III (0–108) score | 23 ± 10 | 17 ± 7.4 | 18.7 ± 9.7 |

| UPDRS-tremor (0–28) score | 5.2 ± 2.5 | 2 ± 0.8 | 0 |

| UPDRS-AK (0–48) score | 9.3 ± 5 | 6.6 ± 3.5 | 10.2 ± 6.6 |

| LEDDs (mg) | 424.6 ± 270 | 356.5 ± 256.1 | 506.0 ± 282.1 |

Table 1B.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the 12 patients enrolled for the audio-visual task (B).

| Patient | Sex | Age | Disease duration | H&Y | UPDRS III—tremor score left/right | UPDRS III—item 22 left/right (AK score) | UPDRS III total score | LEDDs (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 64 | 18 | 2 | 3/2 | 2/2 (13) | 28 | 560 |

| 2 | M | 73 | 10 | 2 | 3/0 | 2/2 (11) | 27 | 510 |

| 3 | M | 56 | 10 | 2 | 2/0 | 1/0 (7) | 20 | 710 |

| 4 | M | 70 | 5 | 2 | 0/2 | 1/2 (5) | 12 | 580 |

| 5 | F | 71 | 4 | 2 | 0/2 | 2/1 (5) | 13 | 610 |

| 6 | M | 73 | 4 | 2 | 3/0 | 2/0 (5) | 19 | 300 |

| 7 | M | 58 | 12 | 2 | 3/1 | 2/2 (8) | 16 | 210 |

| 8 | M | 70 | 4 | 2 | 3/0 | 2/0 (8) | 24 | 480 |

| 9 | M | 69 | 9 | 2 | 0/3 | 2/2 (11) | 23 | 400 |

| 10 | F | 76 | 3 | 2 | 3/1 | 2/2 (11) | 22 | 300 |

| 11 | M | 69 | 6 | 2 | 2/0 | 2/2 (5) | 12 | 255 |

| 12 | M | 65 | 7 | 2 | 0/1 | 2/2 (9) | 18 | 450 |

Each patient's disease severity was assessed using the Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y maximum is 5) stages and the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale part III (UPDRS-III; maximum score is 108). UPDRS item 20 and 21 refer to rest and action or postural tremor; item 22 refers to rigidity. UPDRS akinetic-rigid (AK) score was the sum of items: 18 (speech), 19 (facial expression), 22 (rigidity), 27 (arising from chair), 28 (posture), 29 (gait), 30 (postural stability), 31 (body bradykinesia); tremor score was the sum of items: 20 (tremor at rest), and 21 (action or postural tremor of hands). L - Dopa Equivalent Daily Doses (LEDDs) were recorded as follows: 100 mg levodopa = 1.5 mg pramipexole = 6 mg ropinirole. In Table 1A, values are means ± SD. See text for inclusion criteria.

Table 2 lists DAT binding values. All 12 subjects enrolled for the EMG recording showed a reduced DAT binding value in the striatum (12% and 22% in the ipsilateral and contralateral caudate nucleus; 41% and 53% in the ipsilateral and contralateral putamen), thus further confirming the clinical diagnosis. DAT binding values did not differ between PD subjects with and without tremor in all regions investigated, also when weighted for demographic (age at SPECT, age at onset, gender) and clinical data (disease duration, disease severity, and LEDDs). Of interest, DAT binding values in the pons (where the LC is located) resulted significantly higher in PD patients with tremor when compared to healthy controls. Still, no difference was found between PD with and without tremor within this region.

Table 2.

FP-CIT SPECT binding values.

| Bilateral tremor (n = 27) | One-side tremor (right n = 11; left n = 11) | No tremor (n = 33) | Healthy controls (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal lobe | 0.11 ± 0.08 | 0.07 ± 0.11 | 0.11 ± 0.09 | 0.06 ± 0.08 |

| Cerebellum | 0.12 ± 0.07** | 0.12 ± 0.06** | 0.11 ± 0.09** | 0.05 ± 0.04 |

| Pons | 0.54 ± 0.13* | 0.53 ± 0.11* | 0.49 ± 0.21 | 0.42 ± 0.14 |

| Brainstem | 1.52 ± 1.32 | 1.97 ± 2.14** | 1.85 ± 1.48** | 0.54 ± 0.13 |

| Midbrain | 0.67 ± 0.16 | 0.69 ± 0.13 | 0.63 ± 0.21 | 0.69 ± 0.15 |

| Thalamus contralateral | 0.55 ± 0.14 | 0.57 ± 0.19 | 0.52 ± 0.19 | 0.6 ± 0.13 |

| Thalamus ipsilateral | 0.57 ± 0.14 | 0.6 ± 0.15 | 0.55 ± 0.16 | 0.59 ± 0.17 |

| GPe contralateral | 1.32 ± 0.33** | 1.31 ± 0.26** | 1.22 ± 0.42** | 2 ± 0.32 |

| GPe ipsilateral | 1.32 ± 0.39** | 1.49 ± 0.28** | 1.3 ± 0.42** | 2.2 ± 0.32 |

| GPi contralateral | 1.22 ± 0.28** | 1.21 ± 0.24** | 1.13 ± 0.34** | 1.6 ± 0.33 |

| GPi ipsilateral | 1.21 ± 0.32** | 1.32 ± 0.23** | 1.19 ± 0.33** | 1.76 ± 0.28 |

| Caudate contralateral | 3.14 ± 1.02** | 3.17 ± 0.81** | 3 ± 0.94** | 4.95 ± 0.98 |

| Caudate ipsilateral | 3 ± 0.89** | 3.65 ± 0.85** | 3 ± 0.97** | 4.94 ± 0.96 |

| Putamen contralateral | 2 ± 0.73** | 2 ± 0.59** | 2 ± 0.86** | 4.6 ± 0.83 |

| Putamen ipsilateral | 2.17 ± 0.75** | 2.5 ± 0.64** | 2.22 ± 0.87** | 4.6 ± 0.83 |

Data are shown as means ± SD (with the bilateral occipital cortex as reference region). Contralateral refers to the side opposite to tremor or to the most affected side for patients without tremor. For healthy subjects, we conventionally referred to the right side as ipsilateral. For the one-side tremor group, the ipsilateral brain regions refer to the hemisoma without rest or postural tremor. The absence of tremor (bilaterally or unilaterally) derived by a UPDRS-III score of 0 at the previous visit (within two months) before SPECT and by the anamnestic statement by the patient of having not experienced tremor (bilaterally or at the non-tremor side). FP-CIT uptake values for the caudate nucleus and putamen were calculated according to Basal Ganglia Matching Tool. The FP-CIT uptake values in other brain regions were obtained with the creation, in the shapes menu of WFU Pick Atlas Tool, of specific volumes of interest (VOIs).

DAT binding values did not differ among PD sub-groups (with or without tremor), also when weighted for demographic (age at SPECT, age at onset, gender) and clinical data (disease duration, disease severity, and LEDDs). Therefore, statistical significance is marked only vs. healthy controls.

*p = 0.01; **p < 0.001.

GPe = globus pallidus pars externa; GPi = globus pallidus pars interna.

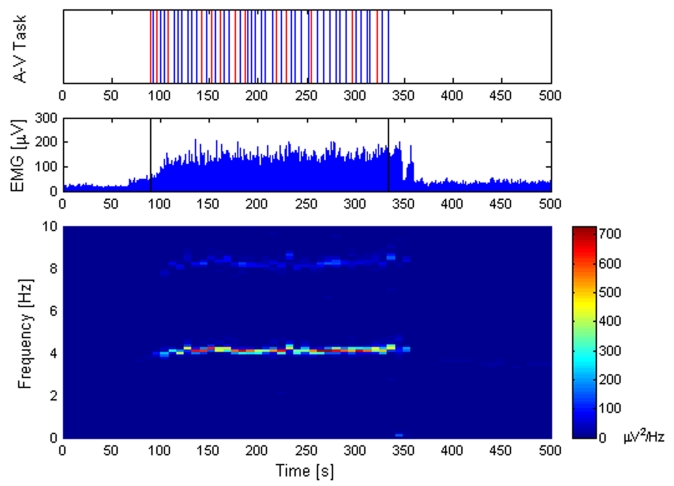

All 12 patients showed the typical parkinsonian rest tremor in the frequency range of 4–6 Hz. No changes in tremor frequency or intensity were found during A-V100 and A-Vnull. On the contrary, tremor intensity greatly and consistently increased during the A-V200 task in all patients (p < 0.001) (Table 3). Interestingly, tremor frequency during the same task did not significantly change (Table 3, first column). The figure illustrates tremor behavior in one patient during one trial with the A-V200 task (n. 4 in Table 3). Note that EMG activity of left EDC (Figure 1, mid box) appears only during the audio-visual task. Interestingly, the power spectral analysis (Figure 1, lower box) clearly describes, during the audio-visual task, an enhancement of tremor intensity and a sustained 4.2 Hz tremor frequency. Similar results were found in all other PD subjects (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes of tremor intensity (i.e., power of EMG signals) during the audio-visual task.

| Patient | Muscle | fPEAK(fAVG) | Pre-task (0–90 s) | A-V200 task (90 s–EoT) | Post-task early (EoT–400 s) | Post-task late (400–500 s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPEAK(PAVG) | PPEAK(PAVG) | PPEAK(PAVG) | PPEAK(PAVG) | |||

| 1 | R-flex | 4.8 (4.6) | 83 (50) | 4250 (1118) | 1975 (296) | – |

| 2 | R-flex | 4.9 (4.9) | – | 14,130 (1405) | 9834 (2704) | 1703 (376) |

| 3 | L-ext | 5.8 (5.8) | 380 (181) | 1755 (912) | 349 (260) | 265 (70) |

| 4 | L-ext | 4.2 (4.2) | – | 800 (296) | 266 (100) | – |

| 5 | R-ext | 4.9 (5.1) | 2686 (819) | 8022 (2240) | 3686 (501) | – |

| 6 | L-opp | 3.9 (3.9) | – | 14,759 (4286) | – | – |

| 7 | L-flex | 4.9 (4.9) | – | 9563 (2937) | 4314 (1552) | – |

| 8 | L-flex | 4.2 (4.2) | – | 7393 (838) | – | – |

| 9 | R-opp | 4.3 (4.2) | 1981 (719) | 8806 (2963) | 1222 (231) | – |

| 10 | L-ext | 5.5 (5.3) | – | 1244 (86) | 145 (35) | 109 (41) |

| 11 | L-opp | 3.9 (3.9) | – | 2907 (267) | – | – |

| 12 | R-opp | 3.5 (3.5) | – | 135 (56) | – | – |

Pre-task refers to a period of 90 s without stimuli preceding the audio-visual task (A-V200). Post-task early refers to the first time period without stimuli after the task end (from End-of-Task (EoT) to 400 s counting from the start of the EMG recording); post-task late refers to the last part of the period without stimuli (from 400 to the end of EMG recording). We listed only the activity of the most-affected muscle. Tremor frequency, when tremor was present, did not change throughout the task. The intensity of tremor significantly increased during the task in all subjects.

fPEAK = peak frequency; fAVG = average frequency; PPEAK = tremor power peak; PAVG = tremor power average; “–“ refers to absence of tremor activity at EMG.

Note that given the randomized presentation of the visual and auditory stimuli, the EoT time differed among subjects (ranging from 127 to 198 s).

Figure 1.

Tremor behavior during the audio-visual (A-V200) task in one patient. Upper box: Audio-visual task (A-V200 task). Red lines indicate when flashed white disk and noise were not simultaneous, blue lines when they were simultaneous. The stimulus onset asynchrony between the visual and the auditory stimuli was set at 200 ms (visual preceding auditory). A total of 50 visual and auditory stimuli were presented. Space between lines indicate time interval (ranging between 2.5 and 7 s). Mid box: EMG recordings (in blue), high-pass filtered off-line at 60 Hz and rectified. Single vertical lines (in black) show the start and end of the A-V200 task, respectively. Lower box: Spectral analysis of tremor activity showing a sustained tremor frequency at 4.2 Hz. The harmonic double tremor frequency is also clearly represented. The power of EMG signals (intensity of tremor) is shown in colors (right column scale).

Discussion

The present study suggests a LC-related activity in the generation of tremor in PD. We also confirmed in an ample homogeneous study population the lack of a correlation between dopaminergic innervation loss and parkinsonian tremor (Isaias et al., 2007).

There is increasing evidence that resting tremor in PD is associated with a distinct cerebello-thalamic circuit involving the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus (Vim), the cerebellum, and the motor cortex. Indeed, a distinct ponto-thalamo-cortical pattern, possibly involving the cerebellum/dentate nucleus, the primary motor cortex, and the caudate/putamen have been identified in tremor-predominant PD patients (Mure et al., 2011). More recently, a selective dopaminergic depletion of the globus pallidus (but not striatum) has been reported to correlate with clinical tremor severity and suggested to link the basal ganglia with the cerebello-thalamic circuit in the onset of rest tremor in PD (Helmich et al., 2011). We failed to find any difference of dopamine innervation loss (including the globus pallidus) between PD subjects with bilateral, unilateral, or without tremor. Indeed, structural lesions of the substantia nigra produce akinetic syndromes but not tremor (Jenner and Marsden, 1984). The role of the cerebellum has been also questioned by a multi-tracer PET study showing that at least part of the cerebellar hyperactivation seen in tremulous PD might be related to akinesia and rigidity (Ghaemi et al., 2002). The development of rest tremor associated with PD in a patient who had prior cerebellectomy further suggested that the cerebellum is not the primary origin of tremor (Deuschl et al., 1999).

The LC is a cluster of NA-containing neurons located in the upper dorsolateral pontine tegmentum. LC neurons fire in a tonic or phasic mode (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). Tonic activity is characterized by sustained and highly regular discharge pattern that is highest during wakefulness, decreases during slow-wave sleep, and virtually ceases during Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep. LC phasic mode involves activation of LC neurons following task-relevant processes in response to environmental stimuli that elicit behavioral arousal and exploratory behavior (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). Animal studies reported that neurons in the LC can show also a synchronous activity. Synchronous oscillations would rely on electronic coupling and are seemingly independent of synaptic transmission. Electrotonic coupling between LC neurons could serve to facilitate synchrony in the event of a large afferent input (Ishimatsu and Williams, 1996).

LC neurons have extensively branched axons that project throughout the neuraxis and provide the sole source of NA to the neocortex, cerebellum, and most of the thalamus (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005), all possibly involved in tremor onset. In particular, the release of NA from LC axons causes inhibition of ongoing purkinje cell activity, thus facilitating one or more functions of regions under purkinje inhibitory control. Noradrenergic input to the thalamic cells promotes a single spike-firing mode of activity in the thalamus that has been related to increased cortical activity and responsiveness. The LC also innervates extensively and it is the sole source of cortical NA. It is likely that this noradrenergic input to the neocortex is excitatory and contributes to the generally recognized role of the LC as a major wakefulness-promoting nucleus (Samuels and Szabadi, 2008a, b).

The biochemistry of NA neurons has great relevance to PD (Delaville et al., 2011; Isaias et al., 2011). Of note, in the normal condition, dopamine β-hydroxylase synthesizes NA from dopamine. The LC-NA system modulates the survival of its target neuronal populations, which include dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (Mavridis et al., 1991; Frey et al., 1997; Rommelfanger and Weinshenker, 2007). The LC may also directly influence the activity of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system. Single-cell recording studies demonstrated a noradrenergic modulation of midbrain dopamine neuronal activity consistent with a direct pathway from the LC to the substantia nigra. In particular, injections of the adrenergic neurotoxin N-(2-Chloroethyl)-N-ethyl-2 bromo benzylamine hydrochloride (DSP-4) in the ventral tegmental area or direct lesioning of the LC by local injection of 6-hydroxy-dopamine (6-OHDA) resulted in a significant decrease in the basal release of dopamine in the caudate nucleus (Collingridge et al., 1979; Lategan et al., 1992), and result in the compensatory up-regulation of striatal D2 receptors (Harro et al., 2003). NA facilitates burst firing of substantia nigra pars compacta, while administration of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin attenuates firing (Grenhoff and Swensson, 1993).

The LC is thought to degenerate in PD as part of the disease pathology (Braak et al., 2003). Still, Lewy pathology poorly correlates with neuronal loss in specific areas, thus its predictive validity for neuronal disintegration is questionable (Jellinger, 2009). Moreover, noradrenergic neurons in the LC are relatively preserved in early PD (Isaias et al., 2011; Pavese et al., 2011) and do not exhibit the same intracellular changes as in the substantia nigra (Halliday et al., 2005). Finally, the LC may degenerate only in specific PD patients (Cash et al., 1987). Of interest, animal studies showed a significantly increased activity of noradrenergic neurons in LC after unilateral lesion of the nigrostriatal pathway (Wang et al., 2009).

Mevawalla and colleagues (Mevawalla et al., 2009) reported a case of unilateral rest tremor in a patient with vascular parkinsonism and contralateral lesion of the LC. The Authors suggest that the unilateral LC lesion contributed to the pathogenesis of contralateral tremor. There are several concerns related to this clinical case that prevent any firm conclusion. The patient suffered from vascular parkinsonism and macroscopically presented vascular lesions in the globus pallidus bilaterally, right putamen and internal capsule. The presence of tongue tremor supports a cerebellar involvement, which was not investigated by the Authors. Moreover, no functional studies have been carried out in vivo, nor functional staining (e.g., TH-staining) in ex vivo specimina. Last but not least, the LC projects almost exclusively ipsilaterally and, therefore, the tremor would relate to the intact LC rather than the lesioned one. This would eventually support, rather than confute our hypothesis. Still, based on our preliminary results, we cannot exclude that tremor in PD derives from a paradoxical effect of NA and dopamine depletion (Dzirasa et al., 2010).

The main limitation of this study relates to poor specificity of the A-V200 task. Still, this task proved to selectively activate the brainstem in an in vivo imaging study (Raizada and Poldrack, 2008). We also did not find changes in tremor activity during A-V100 and A-Vnull trials, both tasks being not able to elicit an activation of brainstem but of other brain areas (i.e., frontal region) (Raizada and Poldrack, 2008).

Secondly, the LC-NA system and the noradrenaline molecular transporters (NET) should be ideally investigated in vivo by dedicated, highly specific radiotracers displaying low background non-NET binding, high sensitivity to variations in NET density, and fast kinetics. As such, a radiotracer is not available for large clinical studies, we retrospectively collected data of SPECT with FP-CIT in a large, homogeneous cohort of PD patients out of our database (Centro per la Malattia di Parkinson e i Disturbi del Movimento, Milano). Although FP-CIT is mainly used for assessing striatal dopamine reuptake transporters (DATs), it has shown some, albeit lower, sensitivity, to NET (Booij and Kemp, 2008). Hence, when applied to an anatomical region with known low DAT capacity such as the LC, it allows investigation on the NA-dependent synaptic activity (Isaias et al., 2011). In the brainstem, no other anatomical region, beside the LC, show clearly detectable density of NET (nor DAT).

Studying the LC can be challenging to say the least. In particular, (1) directly recording in humans the activity of LC is not applicable given its anatomical structure and location; (2) the size of LC is at the spatial resolution limits of currently available imaging techniques; and (3) even receptor binding (or displacement) studies and PET might not catch its phasic electrical activity. Anyhow, along our results, it is tempting to hypothesize an active role of the LC-NA system in triggering tremor onset in PD. While the frequency of parkinsonian tremor might be related to the intrinsic oscillating properties of dopamine depleted circuits, the onset and intensity of tremor might relate to the activity of the LC and of its noradrenergic output.

The introduction of the LC in the neural network dynamics of parkinsonian tremor might well explain many of its remarkable features. In particular, (1) tremor would appear only in PD subject with no functional damages of the LC; (2) eventually, along with PD progression and a consequent degeneration of LC-NA system, tremor will diminish; (3) tremor will appear during maneuvers that trigger LC activity, above all stress; and (4) PD patients do not manifest tremor during sleep being the LC silent. Finally, given a putative neuroprotective and compensatory activity of LC-NA on its target cells (including the substantia nigra and the striatum), it is tempting to speculate that an intact, or hyperactive, LC-NA system might be responsible for a more benign progression of PD in patients with tremor.

In conclusion, parkinsonian tremor would be the outcome of subtle derangements in the finely tuned NA-DA interplay, where the dopaminergic failure would involve complex noradrenergic adjustments leading to motor anomalies in the presence of an intact LC, which might be only a necessary state but not the direct cause of rest tremor in PD.

All these pending questions obviously require further studies in the future both by imaging and laboratory techniques. On this track, we hypothesize that parkinsonian tremor might represent the clinical sign of an enhanced LC activity as possible compensatory process over dopaminergic loss.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by a grant of the Grigioni Foundation for Parkinson disease.

References

- Aston-Jones G., Cohen J. D. (2005). An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 28, 403–450 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booij J., Kemp P. (2008). Dopamine transporter imaging with [123I]FP-CIT SPECT: potential effects of drugs. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 35, 424–438 10.1007/s00259-007-0621-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Del Tredici K., Rüb U., de Vos R. A., Jansen Steur E. N., Braak E. (2003). Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 24, 197–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks D. J., Playford E. D., Ibanez V., Sawle G. V., Thompson P. D., Findley L. J., Marsden C. D. (1992). Isolated tremor and disruption of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system: an 18F-dopa PET study. Neurology 42, 1554–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvini P., Rodriguez G., Inguglia F., Mignone A., Guerra U. P., Nobili F. (2007). The basal ganglia matching tools package for striatal uptake semi-quantification: description and validation. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 34, 1240–1253 10.1007/s00259-006-0357-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash R., Dennis T., L'Heureux R., Raisman R., Javoy-Agid F., Scatton B. (1987). Parkinson's disease and dementia: norepinephrine and dopamine in locus ceruleus. Neurology 37, 42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge G. L., James T. A., MacLeod N. K. (1979). Neurochemical and electrophysiological evidence for a projection from the locus coeruleus to the substantia nigra. J. Physiol. 290, 44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert F. C. (1987). Pharmacological characteristics of tremor, rigidity and hypokinesia induced by reserpine in rat. Neuropharmacology 26, 1431–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constas C. (1962). The effects of adrenaline, noradrenaline, and isoprenaline on parkinsonian tremor. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 25, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaville C., Deurwaerdère P. D., Benazzouz A. (2011). Noradrenaline and Parkinson's disease. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 5, 31. 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschl G., Bain P., Brin M. (1998). Consensus statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor. Ad Hoc Scientific Committee. Mov. Disord. 13, 2–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschl G., Wilms H., Krack P., Würker M., Heiss W. D. (1999). Function of the cerebellum in Parkinsonian rest tremor and Holmes' tremor. Ann. Neurol. 46, 126–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzirasa K., Phillips H. W., Sotnikova T. D., Salahpour A., Kumar S., Gainetdinov R. R., Caron M. G., Nicolelis M. A. (2010). Noradrenergic control of cortico-striato-thalamic and mesolimbic cross-structural synchrony. J. Neurosci. 30, 6387–6397 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0764-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey K., Kilbourn M., Robinson T. (1997). Reduced striatal vesicular monoamine transporters after neurotoxic but not after behavioral-sensitizing doses of methamphetamine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 334, 273–279 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01152-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi M., Raethjen J., Hilker R., Rudolf J., Sobesky J., Deuschl G., Heiss W. D. (2002). Monosymptomatic resting tremor and Parkinson's disease: a multitracer Positron emission tomographic study. Mov. Disord. 17, 782–788 10.1002/mds.10125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenhoff J., Swensson T. H. (1993). Prazosin modulates the firing pattern of dopamine neurons in rat ventral tegmental area. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 233, 79–84 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90351-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday G. M., Ophof A., Broe M., Jensen P. H., Kettle E., Fedorow H. (2005). α-Synuclein redistributes to neuromelanin lipid in the substantia nigra early in Parkinson's disease. Brain 128, 2654–2664 10.1093/brain/awh584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harro J., Terasmaa A., Eller M., Rinken A. (2003). Effect of denervation of the locus coeruleus projections by DSP-4 treatment on [3H]-raclopride binding to dopamine D2 receptors and D2 receptor-G protein interaction in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 976, 209–216 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02677-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmich R. C., Janssen M. J. R., Oyen W. J. G., Bloem B. R., Toni I. (2011). Pallidal dysfunction drives a cerebellothalamic circuit into Parkinson tremor. Ann. Neurol. 69, 269–281 10.1002/ana.22361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaias I. U., Benti R., Cilia R., Canesi M., Marotta G., Gerundini P., Pezzoli G., Antonini A. (2007). [123I]FP-CIT striatal binding in early Parkinson's disease patients with tremor vs. akinetic-rigid onset. Neuroreport 14, 1499–1502 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282ef69f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaias I. U., Marotta G., Pezzoli G., Sabri O., Schwarz J., Crenna P., Classen J., Cavallari P. (2011). Enhanced catecholamine transporter binding in the locus coeruleus of patients with early Parkinson disease. BMC Neurol. 11, 88. 10.1186/1471-2377-11-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaias I. U., Marotta M., Hirano S., Canesi M., Benti R., Righini A., Tang C., Cilia R., Pezzoli G., Eidelberg D., Antonini A. (2010). Imaging essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 25, 679–686 10.1002/mds.22870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimatsu M., Williams J. T. (1996). Synchronous activity in locus coeruleus results from dendritic interactions in pericoerulear regions. J. Neurosci. 16, 5196–5204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger K. A. (2009). Formation and development of Lewy pathology: a critical update. J. Neurol. 256, 270–279 10.1007/s00415-009-5243-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P., Marsden C. D. (1984). “Neurochemical basis of parkinsonian tremor,” in Movement Disorders: Tremor, eds Findley L. J., Capildeo R. (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; ), 305–319 [Google Scholar]

- Lategan A. J., Marien M. R., Colpaert F. C. (1992). Suppression of nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopamine release in vivo following noradrenaline depletion by DSP-4: a microdialysis study. Life Sci. 50, 995–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavridis M., Degryse A. D., Lategan A. J., Marien M. R., Colpaert F. C. (1991). Effects of locus coeruleus on parkinsonian signs, striatal dopamine and substantia nigra cell loss after 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine monkeys: a possible role for the locus coeruleus in progression of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience 41, 507–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mevawalla N., Fung V., Morris J., Halliday G. M. (2009). Unilateral rest tremor in vascular parkinsonism associated with a contralateral lesion of the locus coeruleus. Mov. Disord. 24, 1242–1244 10.1002/mds.22513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mure H., Hirano S., Tang C. C., Isaias I. U., Antonini A., Ma Y., Dhawan V., Eidelberg D. (2011). Parkinson's disease tremor-related metabolic network: characterization, progression, and treatment effects. Neuroimage 54, 1244–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavese N., Rivero-Bosch M., Lewis S. J., Whone A. L., Brooks D. J. (2011). Progression of monoaminergic dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: a longitudinal 18F-dopa PET study. Neuroimage 56, 1463–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizada R. D. S., Poldrack R. A. (2008). Challenge-driven attention: interacting frontal and brainstem systems. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 1, 3. 10.3389/neuro.09.003.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommelfanger K. S., Weinshenker D. (2007). Norepinephrine: the redheaded stepchild of Parkinson disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 74, 177–190 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels E. R., Szabadi E. (2008a). Functional neuroanatomy of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus: its roles in the regulation of arousal and autonomic function part I: principles of functional organisation. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 6, 235–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels E. R., Szabadi E. (2008b). Functional neuroanatomy of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus: its roles in the regulation of arousal and autonomic function part II: physiological and pharmacological manipulations and pathological alterations of locus coeruleus activity in humans. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 6, 254–285 10.2174/157015908785777193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann L., Gross J., Dirks M., Volkmann J., Freund H.-J., Schnitzler A. (2003). The cerebral oscillatory network of parkinsonian resting tremor. Brain 126, 199–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Zhang Q., Liu J., Wu A., Wang S. (2009). Firing activity of locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons increases in a rodent model of Parkinsonism Neurosci. Bull. 25, 15–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur R., Kulik F. A., Kulik A. V. (1988). Noradrenergic effects in tardive dyskinesia, akathisia and pseudoparkinsonism via the limbic system and basal ganglia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 12, 849–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]