Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PLGF) are increased in the maternal circulation during pregnancy. These factors may increase blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, yet brain edema does not normally occur during pregnancy. We therefore hypothesized that in pregnancy, the BBB adapts to high levels of these permeability factors. We investigated the influence of pregnancy-related circulating factors on VEGF-induced BBB permeability by perfusing cerebral veins with plasma from nonpregnant (NP) or late-pregnant (LP) rats (n=6/group) and measuring permeability in response to VEGF. The effect of VEGF, PLGF, and VEGF-receptor (VEGFR) activation on BBB permeability was also determined. Results showed that VEGF significantly increased permeability (×107 μm3/min) from 9.7 ± 3.5 to 21.0 ± 1.5 (P<0.05) in NP veins exposed to NP plasma, that was prevented when LP veins were exposed to LP plasma; (9.7±3.8; P>0.05). Both LP plasma and soluble FMS-like tyrosine-kinase 1 (sFlt1) in NP plasma abolished VEGF-induced BBB permeability in NP veins (9.5±2.9 and 12±2.6; P>0.05). PLGF significantly increased BBB permeability in NP plasma (18±1.4; P<0.05), and required only VEGFR1 activation, whereas VEGF-induced BBB permeability required both VEGFR1 and VEGFR2. Our findings suggest that VEGF and PLGF enhance BBB permeability through different VEGFR pathways and that circulating sFlt1 prevents VEGF- and PLGF-induced BBB permeability during pregnancy. —Schreurs, M. P. H., Houston, E. M., May, V., Cipolla, M. J. The adaptation of the blood-brain barrier to vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor during pregnancy.

Keywords: cerebral endothelium, circulating angiogenic factors, gestation, sFlt1

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) comprises a unique endothelium, compared with endothelium of peripheral organs, in that it lacks fenestrations, contains high electrical resistance tight junctions, and has restricted paracellular flux of ions and proteins (1–3). Under physiological conditions, these unique properties prevent entry of ions and large proteins into the brain from blood and minimize the effect of hydrostatic pressure on capillary filtration of water, all of which result in a strong protective mechanism against vasogenic brain edema (1–4). During normal pregnancy, the endometrium, decidua, and placenta initiate a large increase in release of cytokines and angiogenic growth factors into the circulation (5–8). Many of these growth factors are essential for the increasing demand of the fetal-placental unit and normal intrauterine development of the fetus (6, 8, 9). Several of these factors are vasoactive, can induce vascular permeability (6, 8), and may have the ability to affect BBB permeability. However, despite high levels of these permeability factors produced during pregnancy, vasogenic brain edema does not normally occur (10, 11). Thus, the BBB appears to adapt during normal pregnancy to maintain its protective state in the face of these circulating permeability factors.

One growth factor important for a successful pregnancy is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; ref. 12). It is produced in significantly higher levels during pregnancy by a variety of cells, including endothelial cells, and is increased both locally in the maternal-fetal unit and in the maternal circulation (13, 14). VEGF was initially discovered as a vascular permeability factor, but it is now known to also have important roles in angiogenesis, vascular growth, endothelial cell survival, and vasorelaxation, including in the brain and the cerebral circulation (15–19). VEGF affects BBB permeability through a complex interaction between VEGF and its two VEGF receptors (VEGFRs), known in rats as FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 (Flt1) and fetal liver kinase 1 (Flk1), but also known as VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, respectively. These two receptors can, after phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domains of either Flt1 or Flk1, transphosphorylate adjacent domains (“crosstalk”) and even form Flt1/Flk1 receptor-dimers (15, 19–21). VEGFR-mediated signaling to induce vascular permeability has been studied intensely in peripheral tissues. However, it remains unclear whether Flt1, a receptor with low tyrosine kinase activity compared to Flk1, is involved in VEGF-induced permeability or whether it functions as a nonsignaling reservoir for VEGF (15, 19–23). To our knowledge, little is known about the VEGFR-mediated signaling pathway in the cerebral endothelium to induce BBB permeability. Further, how the brain and BBB might adapt to high levels of the permeability factor VEGF during pregnancy is also not known.

In addition to VEGF, circulating levels of placental growth factor (PLGF), another member of the VEGF family that is highly produced in the placenta during pregnancy, are also significantly elevated in the blood during normal pregnancy (24). PLGF binds only to Flt1 and is involved in angiogenesis and endothelial cell viability, both by inducing its own signaling pathway and by amplifying VEGF-driven actions (20). Although PLGF has been shown to increase vascular permeability in peripheral tissue, whether PLGF also affects the cerebral endothelium to enhance BBB permeability, or through which signaling pathway, is not known (21, 24, 25). Thus, the first goal of this study was to determine whether VEGF or PLGF could induce BBB permeability and by which VEGFR-mediated pathways. Because pregnancy is accompanied by increased levels of VEGF and PLGF in the circulation, our second goal was to investigate the adaptation during pregnancy that might diminish the influence of these permeability factors on BBB permeability.

The bioavailability of VEGF and PLGF is essential for successful pregnancy and is thought to be regulated by antiangiogenic factors, such as soluble Flt1 (sFlt1; refs. 12, 26), a soluble variant of Flt1 that lacks the cytoplasmic domains of Flt1 (27, 28). A third-trimester rise of sFlt1 reflects a physiological antiangiogenic shift of the placental milieu corresponding to the completion of placental growth (5, 6, 29). Because sFlt1 is an important regulator of VEGF-mediated activity in the maternal-fetal unit, we hypothesized that an underlying mechanism by which the BBB is protected from the permeability effects of VEGF during normal pregnancy is through elevated levels of this soluble receptor. Therefore, we determined the influence of sFlt1 on VEGF-induced BBB permeability using levels found in normal pregnancy as well as in preeclampsia, a pregnancy-related hypertensive disorder with increased levels of sFlt1 beyond those of normal pregnancy that causes endothelial dysfunction in peripheral tissues. The influence of sFlt1 on VEGF signaling at the BBB is not known, but likely important, because vasogenic brain edema is involved in neurological complications of preeclampsia (5, 30–33).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female Sprague-Dawley rats were used for all experiments. Female virgin nonpregnant (NP; 260–310 g), or late-pregnant (LP; d 20; 300–340 g) rats were purchased from Charles River (Saint-Constant, QC, Canada). All of the procedures were approved by the University of Vermont Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with the U.S. National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animals were housed in the animal care facility, which is an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care–accredited facility. Animals had access to food and water ad libitum and maintained a 12-h light-dark cycle.

Plasma samples

Plasma samples were obtained from trunk blood from female Sprague-Dawley Rats, either virgin NP or LP (described above). The plasma was collected in plasma separation tubes, pooled from ∼20 rats to minimize biological diversity, and stored at −80°C until experimentation. For all experiments, plasma was diluted to 20% in HEPES buffer.

BBB permeability measurements

The effect of NP and LP rat plasma on BBB permeability and the role of VEGF, PLGF, and sFlt1 were measured as described previously (1), but with slight modification. Briefly, cerebral veins were carefully dissected out of the brain of either NP or LP rats, and the proximal end was mounted on one glass cannula in an arteriograph chamber. Veins were perfused intraluminally with NP (n=6) or LP (n=6) rat plasma in a HEPES buffer and equilibrated for 3 h at 10 ± 0.3 mmHg. After equilibration, intravascular pressure was increased to 25 ± 0.1 mmHg, and the drop due to filtration was measured for 40 min. The decrease of intravascular pressure per minute (mmHg/min) was converted to volume flux through the vessel wall (μm3) using a conversion curve, as described previously (1).

The first set of experiments tested the influence of VEGF and its receptor activation on BBB permeability by perfusing NP cerebral veins with NP plasma with or without the addition of 50 ng/ml VEGF (n=6/group). Receptor activation was determined by the addition of the selective antibodies against VEGFR1 (33 μg/ml for 75% neutralization rate; n=6) or VEGFR2 (4 μg/ml for 90% neutralization rate; n=6). A separate group of vessels was perfused with plasma plus a nonimmune IgG (33 μg/ml; n=6), and permeability was measured as a control for the presence of the antibodies in the lumen.

A second set of experiments was performed to investigate the effect of PLGF on BBB permeability by the addition of 50 ng/ml PLGF to NP rat plasma perfused in an NP vein (n=6). Similarly, VEGFR activation in response to PLGF was determined by measuring permeability after the addition of selective VEGFR1 (33 μg/ml for 75% neutralization rate; n=6) or VEGFR2 (4 μg/ml for 90% neutralization rate; n=6) antibodies.

A third set of experiments was performed to examine the influence of pregnancy on VEGF-induced BBB permeability by measuring permeability after the addition of 50 ng/ml VEGF into NP veins perfused with NP plasma and an LP vein perfused with LP plasma (n=6). To isolate the effect of LP plasma on VEGF-induced BBB permeability, a separate group of NP veins was perfused with LP plasma, and the permeability to VEGF was measured (n=6).

The last set of experiments was performed to determine the influence of sFlt1 on VEGF-induced BBB permeability during pregnancy by perfusing NP veins with 50 ng/ml (n=6) or 500 ng/ml (n=6) sFlt1 in NP plasma and measuring BBB permeability in response to 50 ng/ml VEGF.

Determination of VEGF and VEGFR mRNA expression using real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from individual cerebral veins taken from NP (n=3–5) and LP rats (n=3–7) using the STAT-60 total RNA/mRNA isolation reagent (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX, USA), as described previously (34, 35). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA per sample using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase and random hexamer primers with the SuperScript II Preamplification System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in a 20-μl final reaction volume. All samples were reverse transcribed simultaneously to obviate reaction variability. The quantitative PCR standards for all transcripts were prepared with amplified rat VEGF, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, neuropilin-1, and 18S cDNA products ligated directly into pCR2.1 TOPO vector using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen); the fidelity of the cDNA inserts was verified by direct sequencing. The quantitative PCR primers for the rat transcripts were as follows: VEGF, sense (S) 5′-ATCATGCGGATCAAACCT-3′, antisense (AS) 5′-ATTCACATCTGCTATGCT-3′; VEGFR1, S 5′-AAGACTCGGGCACCTATG-3′, AS 5′-TCGGCACCTATAGACACC-3′; VEGFR2, S 5′-ACGGGGCAAGAGAAATGAAT-3′, AS 5′-GCAAAACACCAAAAGACCAC-3′; neuropilin-1, S 5′-CGCCTGGTGAGCCCTGTGGTCTATT-3′, AS 5′- TGTTCTTGTCGCCTTTCCCTTCTTC-3′. To estimate the relative expression of the receptor transcripts, 10-fold serial dilutions of stock plasmids were prepared as quantitative standards. For real-time quantitative PCR, the reverse-transcribed cDNA samples were diluted 5-fold to minimize the inhibitory effects of the RT reaction components and assayed using SYBR Green I JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 5 mM MgCl2; dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP (200 mM each); 0.64 U of TaqDNA polymerase; and primer (300 nM each) in a final 25-μl reaction volume. The real-time quantitative PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA; refs. 34, 35) as follows: 94°C for 2 min and amplification over 40 cycles at 94°C for 15 s and at 58–62°C (depending on the primer set) for 30 s. SYBR Green I melting analysis of the amplified product from these amplification parameters was carried out by ramping the temperature of the reaction samples from 60–95°C to verify unique product amplification in the quantitative PCR assays. Data analyses were performed with Sequence Detection 1.4 software (Applied Biosystems) using default baseline settings. The standard curves were constructed by amplification of serially diluted plasmids containing the target sequence. The increase in SYBR Green I fluorescence intensity (ΔRn) was plotted as a function of cycle number, and the threshold cycle (CT) was determined by the software as the amplification cycle at which the ΔRn first intersects the established baseline. The transcript levels in each sample were calculated from the CT by interpolation from the standard curve to yield the relative changes in expression. All data were normalized to 18S in the same samples; transcript levels in control NP samples were established as 100%.

Drugs and solutions

HEPES physiological salt solution was made fresh daily and consisted of (mM) 142.0 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.71 MgSO4, 0.50 EDTA, 2.8 CaCl2, 10.0 HEPES, 1.2 KH2PO4, and 5.0 dextrose. VEGF165 (PF074) and PLGF (526610) were purchased from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ, USA). VEGFR1 antibody (AF471), VEGFR2 antibody (AF644), sFlt1 (321-FL), and the goat-IgG antibody control (AB-108-C) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). All drugs were diluted in sterile HEPES without glucose to prevent growth of bacteria and kept frozen at −80°C until use.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± se. Analyses were performed by 1-way ANOVA with a post hoc Student Newman Keuls test for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of circulating VEGF and PLGF on BBB permeability and VEGFR activation

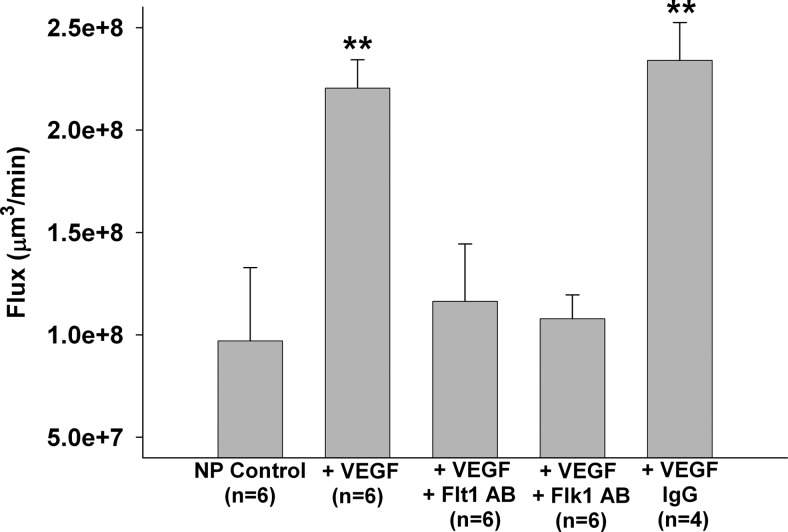

VEGF-induced BBB permeability involves complex signaling by its two receptors (15); however, little is known about VEGFR activation that induces BBB permeability. Thus, we determined BBB permeability in the cerebral vein of Galen from an NP rat perfused with plasma from an NP rat to which 50 ng/ml VEGF was added. The vein of Galen was used for all experiments because this vein has BBB properties and has been shown to be a major site of BBB disruption in pathological states, such as acute hypertension (36). Permeability was also compared between veins that were perfused with selective Flt1 or Flk1 neutralizing antibodies to determine which receptors were involved in permeability. Figure 1 shows that VEGF significantly increased BBB permeability in NP veins. Neutralizing either Flt1 or Flk1 abolished VEGF-induced permeability, suggesting that both receptors are necessary to induce BBB permeability in response to VEGF, with possible crosstalk between the two receptors. The IgG-antibody control group confirmed that the physical presence of the antibody itself in the plasma did not affect VEGF-induced BBB permeability.

Figure 1.

Effect of VEGF on BBB permeability. Flux as a measure of BBB permeability of cerebral veins from NP rats perfused with plasma from NP rats in the absence or presence of 50 ng/ml VEGF. Selective neutralizing antibodies to VEGFR1 or VEGFR2 were also added to determine the role of each receptor in VEGF-induced BBB permeability. VEGF significantly increased BBB permeability. Neutralizing with specific antibodies (AB) for either Flt1 or Flk1 prevented VEGF-induced BBB permeability. The IgG control group showed that the presence of antibody alone did not induce BBB permeability. **P < 0.01 vs. all other groups.

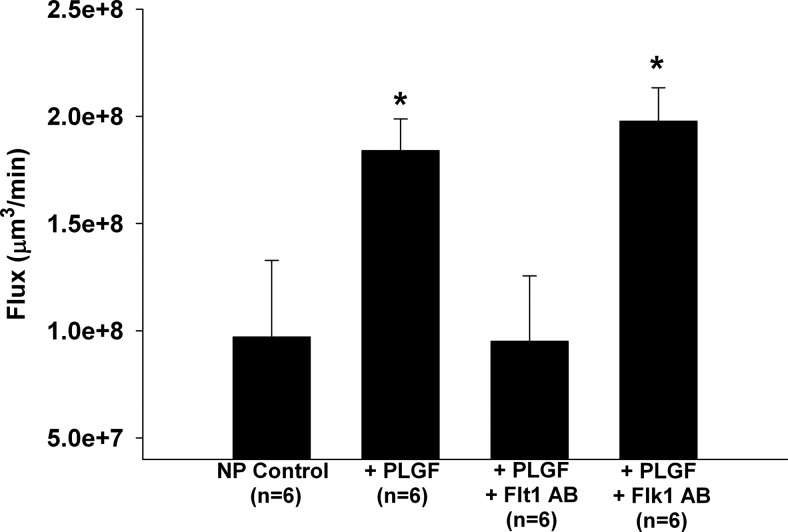

In addition to VEGF, PLGF has been shown to increase peripheral vascular permeability (24, 25), but little is known about the effect of PLGF on BBB permeability. Interestingly, after exposing a vein from an NP rat to NP plasma with 50 ng/ml PLGF, it also significantly increased BBB permeability similar to VEGF (Fig. 2). To our knowledge, these results are the first showing the ability of PLGF to enhance BBB permeability. PLGF is known to interact only with Flt1, with higher affinity than VEGF (21). As expected, selectively neutralizing Flt1, but not Flk1, inhibited PLGF-induced BBB permeability (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of PLGF on BBB permeability. Flux as a measure of BBB permeability of cerebral veins from NP rats perfused with plasma from NP rats in the absence or presence of 50 ng/ml PLGF. Selective neutralizing antibodies to VEGFR1 or VEGFR2 were also added to determine the role of each receptor in PLGF-induced BBB permeability. PLGF also significantly increased BBB permeability to a similar extent as VEGF. Neutralizing Flt-1, but not Flk1, abolished the PLGF-induced BBB permeability. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups.

mRNA expression of VEGF and the VEGFRs in cerebral veins during pregnancy

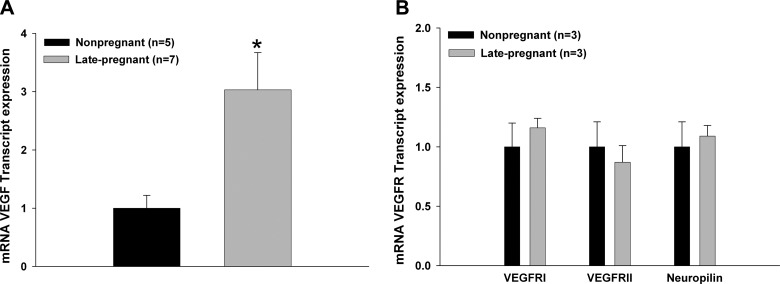

During pregnancy, VEGF is highly expressed in peripheral tissue beyond that of the nonpregnant state (37). However, whether VEGF expression is altered in cerebral vascular tissue during pregnancy that might affect BBB permeability is not known. Thus, we determined the expression of VEGF and its receptors in cerebral veins by qPCR from NP and LP rats. Figure 3A shows that VEGF mRNA expression was significantly increased in veins from LP vs. NP rats. However, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 mRNA expression was similar in veins from LP and NP rats (Fig. 3B). Also, the expression of the neuropilin receptor, a receptor that enhances VEGFR activity (22), did not change. Thus, pregnancy caused increased VEGF expression in the cerebral circulation without an increase in VEGFR expression.

Figure 3.

Effect of pregnancy on VEGF and VEGFR expression in cerebral veins using qPCR. A) mRNA expression of VEGF in cerebral veins from NP and LP rats. Expression of VEGF was significantly increased during pregnancy in cerebral veins. B) mRNA expression of VEGFRs: VEGFR1 (Flt1), VEGFR2 (Flk1). and neuropilin in cerebral veins from NP and LP rats. There was no change in VEGFR expression with pregnancy. *P < 0.05 vs. NP.

The effect of plasma and sFlt1 on VEGF-induced BBB permeability in pregnancy

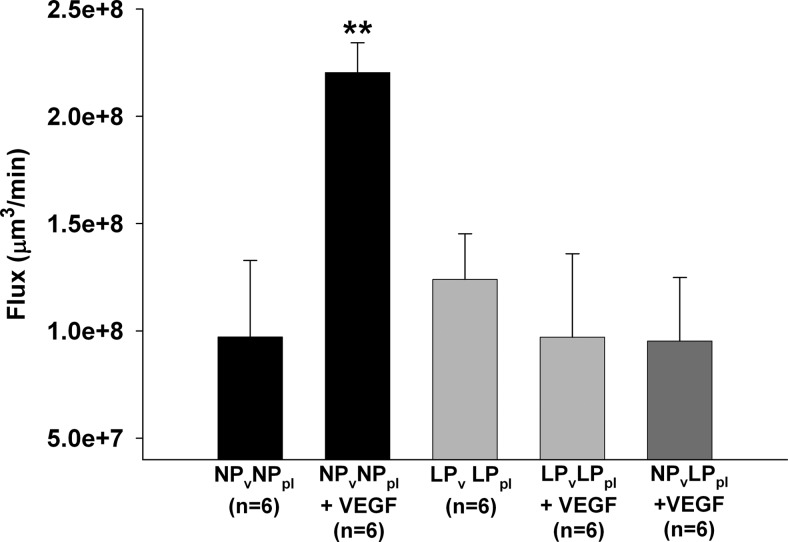

Circulating angiogenic factors during pregnancy may have an important role in protecting the BBB from permeability effects caused by factors such as VEGF and PLGF. Thus, we examined the role of circulating factors during pregnancy in mediating VEGF-induced BBB permeability. We chose VEGF as a well-known and widely accepted representative of all permeability factors in the VEGF family and thereby focused further experiments on examining the effect of VEGF. We compared permeability in veins from NP rats perfused with NP plasma to that in veins from LP rats perfused with LP plasma and measured BBB permeability in response to VEGF. Similar to the above result, Fig. 4 shows that VEGF significantly increased BBB permeability in veins from NP animals perfused with NP plasma. However, VEGF had no effect on BBB permeability in veins from LP animals perfused with LP plasma. To determine whether the lack of response to VEGF in veins from LP rats perfused with LP plasma was due to circulating factors in the LP plasma or to the vasculature being from LP animals, we perfused a cerebral vein from an NP animal with plasma from an LP animal and measured BBB permeability in response to VEGF. Notably, LP plasma prevented the increase in BBB permeability in response to VEGF in NP veins, suggesting that circulating factors in the LP plasma were responsible for the prevention of VEGF-induced BBB permeability during pregnancy.

Figure 4.

Effect of pregnant plasma on VEGF-induced BBB permeability. Flux as a measure of BBB permeability in response to 50 ng/ml VEGF in cerebral veins from NP rats (NPv) perfused with NP plasma (NPpl) and veins from LP rats (LPv) perfused with LP plasma (LPpl). VEGF-induced permeability was prevented in LP vessels perfused with LP plasma. The lack of response to VEGF during pregnancy was due to circulating factors present in LP plasma, since perfusing LP plasma in a cerebral vein from an NP rat also prevented VEGF-induced BBB permeability. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups.

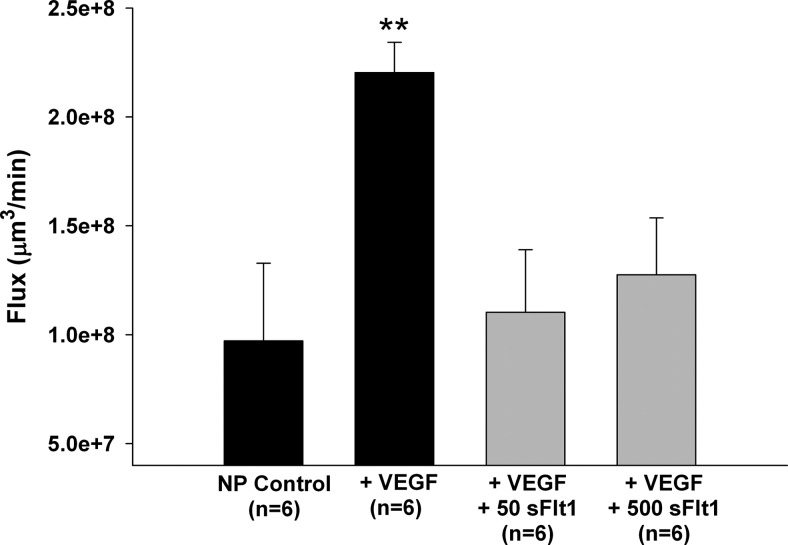

Because elevated sFlt1 could be responsible for preventing VEGF-induced BBB permeability in LP plasma, we determined the specific effect of sFlt1 on VEGF-induced BBB permeability by perfusing NP plasma with 50 ng/ml sFlt1 into a vein from an NP rat and measuring BBB permeability in response to VEGF. We found that VEGF-induced BBB permeability was abolished by the presence of sFlt1, confirming the importance of sFlt1 in controlling VEGF actions at the BBB (Fig. 5). Because excess levels of sFlt1 that lead to an angiogenic imbalance are thought to be important in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, we created this angiogenic imbalance by increasing the sFlt1:VEGF ratio from 1 to 10, similar to preeclampsia (31, 38). In this angiogenic imbalance, sFlt1 is thought to not only control VEGF-induced angiogenesis, but to also inhibit other VEGF-mediated actions which can result in vasoconstriction and endothelial cell damage (12, 32). Interestingly, VEGF-induced BBB permeability was abolished similarly compared to the lower and more physiological concentration of sFlt1 (Fig. 5). Thus, sFlt1 also regulates VEGF-induced permeability at a high sFlt1:VEGF ratio, and does not appear to cause endothelial dysfunction in these cerebral veins.

Figure 5.

Effect of sFlt1 on VEGF-induced BBB permeability. VEGF-induced permeability in cerebral veins from NP rats exposed to NP plasma was prevented by sFlt1 at both 50 and 500 ng/ml, suggesting that sFlt1 is an important circulating factor released during pregnancy that controls VEGF-induced permeability. **P < 0.01 vs. all other groups.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of this study was that circulating factors in LP plasma prevented VEGF-induced BBB permeability and preserved barrier function during pregnancy in the face of high circulating angiogenic factors. BBB permeability without exogenous VEGF was similar in both the NP and LP states, despite the finding that veins from LP rats showed increased VEGF mRNA expression. Exogenous VEGF initiated a significant increase in BBB permeability in the NP state, while it did not affect BBB permeability in LP. Interestingly, after exposing a vein from an NP rat to LP plasma with VEGF, increased BBB permeability was prevented, suggesting circulating factors in the LP plasma were responsible for this adaptation that limited the permeability effects of VEGF. Furthermore, sFlt1 regulated VEGF-induced permeability similar to LP plasma in that it abolished permeability in response to VEGF. Lastly, our results showed that PLGF had similar potential as VEGF to enhance BBB permeability. However, VEGF and PLGF appear to induce BBB permeability through distinct VEGFR activation; e.g., PLGF-induced BBB permeability acted through Flt1, whereas VEGF-induced BBB permeability required activation from both receptors.

The BBB contains unique endothelium that provides a strong protective mechanism against edema in the brain (2, 3). From our results here measuring transvascular water flux, VEGF can clearly increase BBB permeability. This finding is similar to what was found in previous studies measuring solute permeability of cerebral venules in vivo (16, 36). In pregnancy, significant higher expression and levels of VEGF have been measured in the periphery and circulation, which is necessary for the development and maintenance of the maternal-fetal unit and uteroplacental circulation (5, 6, 12, 13). Increased VEGF during pregnancy might also increase BBB permeability and promote edema formation. It is known that VEGF is expressed in the cerebral tissue regulating microvascular permeability (39), but the expression of VEGF in the brain during pregnancy, or the effect of VEGF on the BBB permeability in normal pregnancy, have not been examined previously. Our results showed that similar to other tissues, there is increased expression of VEGF in cerebral veins during pregnancy, suggesting that the cerebral circulation may also be affected by higher levels of VEGF during pregnancy. Few studies examined the effects of VEGF on the BBB, and have shown increased expression of VEGF in the brain and in the cerebral circulation during brain injury that also caused vasogenic edema (16, 39, 40). However, our results showed no increase in BBB permeability in pregnancy (Fig. 4), despite increased expression of VEGF in the cerebral veins. There are two possible explanations for these findings. First, the BBB itself might adapt to the increased levels of VEGF during pregnancy through altered VEGFR expression in cerebral veins. Osol et al. (41) examined VEGFR expression in uterine vessels and found increased VEGFR1 expression during pregnancy, accompanied by increased uterine venous permeability. In contrast, our results showed no increased expression of VEGFRs in the cerebral veins and also no increase in BBB permeability. This could reflect a possible protective mechanism in the brain compared to the uterine circulation that requires increased vascular permeability for controlled extravasation of intravenous molecules in the maternal-fetal unit (42), while the BBB must maintain its protective state to prevent brain edema.

A second explanation for the apparent discrepancy between increased VEGF expression in the cerebral circulation and the lack of VEGF-induced BBB permeability during pregnancy is that there are circulating factors present in the LP plasma protecting the BBB from VEGF-induced BBB permeability. Our results showed that permeability in response to VEGF was prevented by LP plasma, supporting this concept. One important candidate is sFlt1, which is elevated during pregnancy along with VEGF. It selectively binds VEGF and is an important regulator of the bioavailability of VEGF in both the nonpregnant and pregnant state. Our results here confirmed the importance of increased sFlt1 in normal pregnancy controlling the permeability actions of VEGF in the cerebral circulation as addition of sFlt1 in NP plasma abolished VEGF-induced BBB permeability. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that sFlt1 controlled the actions VEGF during pregnancy in the maternal peripheral circulation (6, 12). However, this is the first study that we are aware of showing sFlt1 critically regulates VEGF action at the BBB.

Although sFlt1 appeared to have an important role in limiting VEGF-induced BBB during normal pregnancy, it is also generally accepted that excess levels of sFlt1 are involved in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and might cause endothelial damage (12, 31–33). In this study, we measured VEGF-induced BBB permeability with a 10-fold higher concentration of sFlt1 than in the physiological condition of pregnancy. The VEGF-induced BBB permeability was abolished by higher concentrations of sFlt1 similarly as the physiological concentration. Thus, after acute exposure of increased sFlt1:VEGF ratio in cerebral veins, it did not appear to cause endothelial damage or have a greater effect on BBB permeability. However, this interpretation is limited because of the rather short exposure of the BBB to sFlt1 (3 h). In addition, other cytokines present during pregnancy and preeclampsia were not examined in this study. However, previous studies also raised questions about the connection between sFlt1 with the etiology of neurological complications of preeclampsia. For example, Maynard et al. (27) infused rats with high sFlt1 and found that these rats showed symptoms of preeclampsia, but none had complications of HELLP syndrome or eclampsia. Karumanchi et al. (10) also did not find BBB disruption in rats exposed to high sFlt1, but did find some BBB disruption in rat models exposed to both sFlt1 and soluble endoglin (sEng), suggesting that an interaction of cytokines may be necessary for inducing vasogenic edema in preeclampsia. It is worth noting that these previous studies lacked appropriate controls for both pregnancy and hypertension; i.e., high sFlt1 likely causes similar effects in NP animals, or the effects noted may be due to hypertension and not sFlt1. A recent study showed that sFlt1 did not cause endothelial damage itself, but sensitized VEGFRs to proinflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, resulting in endothelial damage (43). This finding could explain why in the present study exposure to excess sFlt1 did not increase BBB permeability and also why in previous studies rats treated with excess sFlt1 alone did not induce brain edema and neurological complications of preeclampsia. Further, the association between sFlt1 and other proinflammatory cytokines present in preeclampsia, such as TNF-α, could explain why in normal pregnancy, a state with high levels of sFlt1, no apparent endothelial damage occurs.

In addition to VEGF, PLGF is also increased during pregnancy. This factor also has been shown to have permeability effects in the periphery (44), but to our knowledge, no previous study has examined the effect of PLGF on BBB permeability. Previous studies showed that, similar to VEGF, PLGF is a strong vasodilator (41); however, the role of PLGF in permeability during pregnancy was not investigated. Our results show, for the first time, that PLGF significantly increased BBB permeability and is a permeability factor in the cerebral endothelium. Little is known about the signaling pathway of PLGF that increases BBB permeability. In the present study we examined the receptor activation of both VEGF and PLGF and showed that PLGF-induced permeability was, as expected, abolished after neutralizing Flt1, but not after neutralizing Flk1. However, we also found that in contrast to PLGF, neutralizing either Flt1 or Flk1 abolished VEGF-induced BBB permeability, suggesting these two related factors need different receptor activation and possibly act through different signaling pathways to affect BBB permeability. Autiero et al. (21) found using mass spectrometry that PLGF and VEGF interact with Flt1 with distinct patterns of tyrosine phosphorylation. This result is consistent with our findings that VEGF and PLGF appear to act through different receptor activation. Other studies also found that both VEGFRs are able to form heterodimers, especially after binding of VEGF, but not after binding PLGF (21, 45). Further studies are needed to understand the distinct and complex signaling of VEGFRs after binding PLGF or VEGF in the cerebral endothelium that can affect BBB permeability.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study found that VEGF and PLGF both induce BBB permeability through distinct VEGFR-mediated pathways. In addition, circulating sFlt1 controls the permeability actions of VEGF during pregnancy that may prevent vasogenic edema in normal gestation. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing effects of VEGF, PLGF, and sFlt1 on the BBB during normal pregnancy. The finding that increased sFlt1 protects the BBB against VEGF-induced permeability raises some new questions about the role of high sFlt1 in the onset of neurological complications in preeclampsia. As high sFlt1 appears to be protective of the BBB, there may be other proinflammatory factors released during preeclampsia, but not during normal pregnancy, that are responsible for increased BBB permeability and edema formation. Thus, these results may be important for understanding VEGF- and PLGF-induced BBB permeability during normal pregnancy when these factors are increased, but also for understanding the pathogenesis of neurological complications in preeclampsia.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant RO1 NS045940, the Neural Environment Cluster supplement RO1 NS045940-06S1, and ARRA supplement RO1 NS045940-05S1. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the support of U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant PO1 HL095488 and of the Totman Medical Research Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1. Roberts T. J., Chapman A. C., Cipolla M. J. (2009) PPAR-gamma agonist rosiglitazone reverses increased cerebral venous hydraulic conductivity during hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H1347–H1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abbott N. J., Ronnback L., Hansson E. (2006) Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rubin L. L., Staddon J. M. (1999) The cell biology of the blood-brain barrier. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 11–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cipolla M. J. (2007) Cerebrovascular function in pregnancy and eclampsia. Hypertension 50, 14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brett C, Young R. J. L., Ananth S., Karumanchi (2009) Pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 5, 173–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zygmunt M., Herr F., Munstedt K., Lang U., Liang O. D. (2003) Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis in pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 110(Suppl. 1), S10–S18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valdes G., Erices R., Chacon C., Corthorn J. (2008) Angiogenic, hyperpermeability and vasodilator network in utero-placental units along pregnancy in the guinea-pig (Cavia porcellus). Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 6, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Valdes G., Corthorn J. Review: the angiogenic and vasodilatory utero-placental network. Placenta 32(Suppl. 2), S170–S175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Banks R. E., Forbes M. A., Searles J., Pappin D., Canas B., Rahman D., Kaufmann S., Walters C. E., Jackson A., Eves P., Linton G., Keen J., Walker J. J., Selby P. J. (1998) Evidence for the existence of a novel pregnancy-associated soluble variant of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, Flt-1. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 4, 377–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karumanchi S. A., Lindheimer M. D. (2008) Advances in the understanding of eclampsia. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 10, 305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Euser A. G., Cipolla M. J. (2007) Cerebral blood flow autoregulation and edema formation during pregnancy in anesthetized rats. Hypertension 49, 334–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Espinoza J., Uckele J. E., Starr R. A., Seubert D. E., Espinoza A. F., Berry S. M. (2010) Angiogenic imbalances: the obstetric perspective. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 203, 17 e11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amburgey O. A., Chapman A. C., May V., Bernstein I. M., Cipolla M. J. (2010) Plasma from preeclamptic women increases blood-brain barrier permeability: role of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Hypertension 56, 1003–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Evans P., Wheeler T., Anthony F., Osmond C. (1997) Maternal serum vascular endothelial growth factor during early pregnancy. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 92, 567–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olsson A. K., Dimberg A., Kreuger J., Claesson-Welsh L. (2006) VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7, 359–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mayhan W. G. (1999) VEGF increases permeability of the blood-brain barrier via a nitric oxide synthase/cGMP-dependent pathway. Am. J. Physiol. 276, C1148–C1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Monacci W. T., Merrill M. J., Oldfield E. H. (1993) Expression of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor in normal rat tissues. Am. J. Physiol. 264, C995–C1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Breen E. C. (2007) VEGF in biological control. J. Cell. Biochem. 102, 1358–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holmes K., Roberts O. L., Thomas A. M., Cross M. J. (2007) Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2: structure, function, intracellular signalling and therapeutic inhibition. Cell. Signal. 19, 2003–2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roy H., Bhardwaj S., Yla-Herttuala S. (2006) Biology of vascular endothelial growth factors. FEBS Lett. 580, 2879–2887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Autiero M., Waltenberger J., Communi D., Kranz A., Moons L., Lambrechts D., Kroll J., Plaisance S., De Mol M., Bono F., Kliche S., Fellbrich G., Ballmer-Hofer K., Maglione D., Mayr-Beyrle U., Dewerchin M., Dombrowski S., Stanimirovic D., Van Hummelen P., Dehio C., Hicklin D. J., Persico G., Herbert J. M., Communi D., Shibuya M., Collen D., Conway E. M., Carmeliet P. (2003) Role of PlGF in the intra- and intermolecular cross talk between the VEGF receptors Flt1 and Flk1. Nat. Med. 9, 936–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takahashi H., Shibuya M. (2005) The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGF receptor system and its role under physiological and pathological conditions. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 109, 227–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zachary I., Gliki G. (2001) Signaling transduction mechanisms mediating biological actions of the vascular endothelial growth factor family. Cardiovasc. Res. 49, 568–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Makrydimas G., Sotiriadis A., Savvidou M. D., Spencer K., Nicolaides K. H. (2008) Physiological distribution of placental growth factor and soluble Flt-1 in early pregnancy. Prenat. Diagn. 28, 175–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oura H., Bertoncini J., Velasco P., Brown L. F., Carmeliet P., Detmar M. (2003) A critical role of placental growth factor in the induction of inflammation and edema formation. Blood 101, 560–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tripathi R., Rath G., Ralhan R., Saxena S., Salhan S. (2009) Soluble and membranous vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia. Yonsei Med. J. 50, 656–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maynard S. E., Venkatesha S., Thadhani R., Karumanchi S. A. (2005) Soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Pediatr. Res. 57, 1R–7R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shibuya M. (2001) Structure and dual function of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (Flt-1). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 33, 409–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levine R. J., Maynard S. E., Qian C., Lim K. H., England L. J., Yu K. F., Schisterman E. F., Thadhani R., Sachs B. P., Epstein F. H., Sibai B. M., Sukhatme V. P., Karumanchi S. A. (2004) Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 672–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cipolla M. J., Kraig R. P. (2011) Seizures in women with preeclampsia: mechanisms and management. Fetal Matern. Med. Rev. 22, 91–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vaisbuch E., Whitty J. E., Hassan S. S., Romero R., Kusanovic J. P., Cotton D. B., Sorokin Y., Karumanchi S. A. (2010) Circulating angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in women with eclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 204, 152.e151–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Foidart J. M., Schaaps J. P., Chantraine F., Munaut C., Lorquet S. (2009) Dysregulation of anti-angiogenic agents (sFlt-1, PLGF, and sEndoglin) in preeclampsia–a step forward but not the definitive answer. J. Reprod. Immunol. 82, 106–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maynard S. E., Min J. Y., Merchan J., Lim K. H., Li J., Mondal S., Libermann T. A., Morgan J. P., Sellke F. W., Stillman I. E., Epstein F. H., Sukhatme V. P., Karumanchi S. A. (2003) Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 649–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Girard B. M., May V., Bora S. H., Fina F., Braas K. M. (2002) Regulation of neurotrophic peptide expression in sympathetic neurons: quantitative analysis using radioimmunoassay and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Regul. Pept. 109, 89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klinger M. B., Girard B., Vizzard M. A. (2008) p75NTR expression in rat urinary bladder sensory neurons and spinal cord with cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis. J. Comp. Neurol. 507, 1379–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mayhan W. G. (1995) Role of nitric oxide in disruption of the blood-brain barrier during acute hypertension. Brain Res. 686, 99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chrusciel M., Ziecik A. J., Andronowska A. (2010) Expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-A) and its receptors in the umbilical cord in the course of pregnancy in the pig. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 46, 434–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rajakumar A., Powers R. W., Hubel C. A., Shibata E., von Versen-Hoynck F., Plymire D., Jeyabalan A. (2009) Novel soluble Flt-1 isoforms in plasma and cultured placental explants from normotensive pregnant and preeclamptic women. Placenta 30, 25–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fischer S., Clauss M., Wiesnet M., Renz D., Schaper W., Karliczek G. F. (1999) Hypoxia induces permeability in brain microvessel endothelial cells via VEGF and NO. Am. J. Physiol. 276, C812–C820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hayashi T., Abe K., Suzuki H., Itoyama Y. (1997) Rapid induction of vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Stroke 28, 2039–2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Osol G., Celia G., Gokina N., Barron C., Chien E., Mandala M., Luksha L., Kublickiene K. (2008) Placental growth factor is a potent vasodilator of rat and human resistance arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 294, H1381–H1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Celia G., Osol G. (2005) Mechanism of VEGF-induced uterine venous hyperpermeability. J. Vasc. Res. 42, 47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cindrova-Davies T., Sanders D. A., Burton G. J., Charnock-Jones D. S. (2010) Soluble FLT1 sensitizes endothelial cells to inflammatory cytokines by antagonizing VEGF receptor-mediated signalling. Cardiovasc. Res. 89, 671–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Odorisio T., Schietroma C., Zaccaria M. L., Cianfarani F., Tiveron C., Tatangelo L., Failla C. M., Zambruno G. (2002) Mice overexpressing placenta growth factor exhibit increased vascularization and vessel permeability. J. Cell Sci. 115, 2559–2567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Waltenberger J., Mayr U., Pentz S., Hombach V. (1996) Functional upregulation of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor KDR by hypoxia. Circulation 94, 1647–1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]