Abstract

Purpose

Primary congenital glaucoma (PCG) is an autosomal recessive form of glaucoma that manifests within the first year of life and if left untreated, leads to irreversible blindness. Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1) is the major gene known to be associated with PCG. The role of the CYP1B1 gene in disease pathogenesis and the relatively low detection rate of CYP1B1 mutations in some populations, especially Asians, remain unexplained. We hypothesized that altered gene dosage of CYP1B1 or anterior segmental dysgenesis causative genes may be involved in the pathogenesis of PCG.

Methods

We performed whole genome exon-focused array comparative genome hybridization (aCGH) to identify copy number variation (CNV) in 20 Korean PCG patients and their parents.

Results

We identified 12 patients with at least one rare gene-containing copy number variation each, corresponding to 25 CNVs (5 deletions and 20 duplications) at frequencies of 5-30% in PCG patients and 0% in controls. The 25 CNVs were not located at known chromosomal loci for PCG, namely GLC3A, which harbors CYP1B1 (2p21), GLC3B (1p36.2-p36.1), or GLC3C (14q23), and did not include any target genes associated with PCG or anterior segmental dysgenesis.

Conclusions

Further genetic studies with larger cohorts of patients are necessary to validate our results and to elucidate other genetic mechanisms underlying PCG, because the identified CNVs might be PCG-specific pathogenic variants and may explain the disease pathogenesis of PCG.

Introduction

Primary congenital glaucoma (PCG), an autosomal recessive disorder of the eye that usually manifests within the first year of life, is caused by developmental defects in the trabecular meshwork and anterior chamber angle [1]. These developmental defects cause obstruction of aqueous outflow, leading to increased intraocular pressure and optic nerve damage. If left untreated, PCG leads to irreversible blindness [2].

Three loci for PCG (gene symbol GLC3), namely GLC3A (chromosome 2p2-p21), GLC3B (chromosome 1p36.2-p36.1), and GLC3C (chromosome 14q23), have been mapped by linkage analysis [3-5]. Cytochrome p450 1B1 (CYP1B1; OMIM 601771), which is associated with GLC3A, is known to be the major gene associated with PCG. The coding and promoter regions of CYP1B1 have been screened extensively in PCG patients worldwide. However, the pathway by which CYP1B1 affects development of the anterior chamber of the eye remains unknown. In addition, the prevalence of CYP1B1 mutations varies in different populations, ranging from ~10% in Mexico to 100% in consanguineous Slovakian Gypsy patients. The incidence of CYP1B1 gene involvement in Korean, Chinese, and Japanese PCG patients is relatively low (~20%), which means that it is not possible to explain the genetic pathogenesis of PCG in more than half of patients who do not have any CYP1B1 mutations or only one mutant CYP1B1 allele [6-10]. To try to explain these findings, we noted that anterior segmental dysgenesis (ASD) disorders such as Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome, Peters’ anomaly, and iris hypoplasia, are associated with raised intraocular pressure and an increased incidence of glaucoma. Furthermore, the eye is exquisitely sensitive to both reduced and increased doses of key developmental genes such as paired box 6 (PAX6) and forkhead box C1 (FOXC1), as demonstrated in ASD [11-15].

In this context, we expanded the disease spectrum of PCG to ASD and hypothesized that identification of underlying genomic imbalances could lead to elucidation of other genetic mechanisms underlying PCG. Therefore, our aim in this study was to explore alternative genetic mechanisms related to disease pathogenesis in PCG. We performed whole genome exon-focused array CGH (aCGH) to investigate the most susceptible copy number variations (CNVs) in 20 PCG patients and their parents. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first gene dosage analysis of PCG patients using aCGH.

Methods

Patients and clinical evaluation

Twenty Korean PCG patients and their unaffected parents were recruited during a multi-institutional collaborative study from September 2008 to February 2010 and included in this study. Clinical data including CYP1B1 and myocillin (MYOC) sequencing results of subjects with PCG are shown in Table 1. Criteria for PCG diagnosis were evaluated when examination was possible and included IOP ≥21 mmHg in at least one eye; megalocornea; corneal edema/clouding/opacity; and glaucomatous optic nerve head damage. Corroborating features included symptoms of epiphora and photophobia. Patients with other ocular or systemic anomalies were excluded. Of the 20 PCG patients, only two patients had a known heterozygous mutation and a novel mutation in CYP1B1 and MYOC, respectively.

Table 1. Clinical data including CYP1B1 and MYOC sequencing results of subjects with primary congenital glaucoma.

| Individual number | Gender | Age of onset (months) | Affected eye(s) | IOP at diagnosis (OD;OS) | Family history | CYP1B1 mutation | MYOC mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

M |

10 |

U |

22 |

- |

- |

- |

| 2 |

M |

3 |

B |

22/16 |

- |

- |

- |

| 3 |

M |

76 |

B |

30/24 |

Sibling |

- |

- |

| 4 |

F |

21 |

B |

34/17 |

- |

- |

- |

| 5 |

F |

<1 |

B |

30/32 |

- |

- |

- |

| 6 |

M |

29 |

U |

34 |

- |

- |

L228S (heterozygote) |

| 7 |

F |

<1 |

U |

23 |

- |

- |

- |

| 8 |

F |

<1 |

U |

22.4 |

- |

- |

- |

| 9 |

F |

117 |

B |

11/44 |

- |

- |

- |

| 10 |

M |

5 |

U |

33/15 |

- |

- |

- |

| 11 |

F |

3 |

U |

28 |

- |

- |

- |

| 12 |

F |

1 |

U |

18.5 |

- |

- |

- |

| 13 |

F |

35 |

U |

30 |

- |

- |

- |

| 14 |

F |

10 |

B |

52/52 |

- |

- |

- |

| 15 |

F |

5 |

U |

28 |

- |

- |

- |

| 16 |

M |

6 |

U |

22.5 |

- |

- |

|

| 17 |

M |

4 |

B |

37/35 |

- |

A330F (heterozygote) |

- |

| 18 |

M |

2 |

B |

26/32 |

- |

- |

- |

| 19 |

M |

10 |

U |

18.5 |

- |

- |

- |

| 20 | F | 1 | B | 21/30 | - | - | - |

Abbreviation: U, unilateral; B, bilateral.

Array CGH analysis

To identify highly susceptible CNVs in PCG compared with control individuals, we performed aCGH on 20 PCG patients and their parents along with 99 healthy individuals. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). A total of 159 DNA samples were labeled and co-hybridized to determine DNA copy number changes in deletion/duplication using the NimbleGen Human CGH 3x720K Whole Genome Exon-Focused Array (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Arrays were washed and then scanned using a NimbleGen MS 200 Microarray Scanner with 2 µm scanning resolution. Raw copy number data were normalized using Nexus software 5.0 (Nexus BioDiscovery, El Segundo, CA). All probe coordinates were mapped to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) human genome assembly Build 36 (UCSC hg18). The normalized data were then processed with quality controls using Nexus Software and the manufacturer’s recommended default settings. To remove wave artifacts, we checked the number of aligned probes with signal quality and applied lowess correction to the log2 ratios. The same CNV types were merged with adjacent CNV calls using the criteria of ≤10 probes and ≤50 kb apart. The data were loaded into the Fast Adaptive States Segmentation Technique (FASST) segmentation algorithm with a significance threshold of 1.0×10−5. To minimize the number of false positive CNV calls without compromising the sensitivity of detection of true CNVs, we applied log2 ratios with thresholds of 0.3 in gain signals and −0.5 in loss signals. We visually inspected each sample, and excluded CNVs with <5 probes or CNVs ≤500 bp in length.

Identification of copy number variations

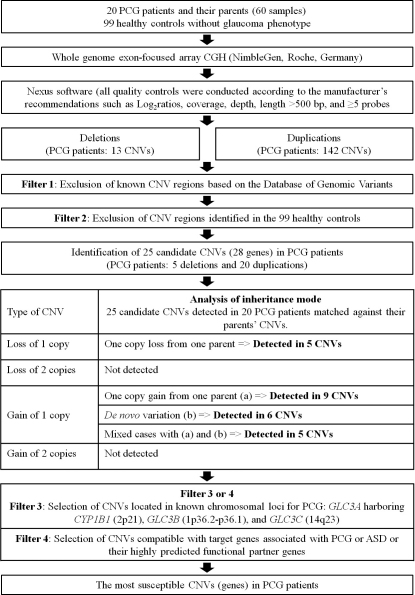

The CNV filtering strategy that we used is summarized in Figure 1. To describe the candidate CNVs, we used the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV; The Centre for Applied Genomics, Toronto, Canada) to determine whether the CNVs were novel or known. We excluded known CNVs in DGV and those identified in controls, and determined candidate genes using the identified CNVs.

Figure 1.

Summary of the copy number variation filtering strategy used in this study.

We then matched the candidate genes detected in PCG patients against their parents’ CNVs to analyze the mode of inheritance. The identified CNVs were classified according to type (Figure 1) and we evaluated whether they were responsible for the disease phenotype of the patients or not.

To narrow down the potential candidate CNVs (genes) and match the identified CNVs to target regions and/or genes, we first focused on known chromosomal loci for PCG, namely GLC3A (2p2-p21), which harbors CYP1B1, GLC3B (1p36.2-p36.1), and GLC3C (14q23). Second, candidate genes with identified CNVs were matched against both PCG-related genes and ASD causative genes including CYP1B1, MYOC, latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein 2 (LTBP2), PAX6, paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2 (PITX2), PITX3, FOXC1, forkhead box E3 (FOXE3), eyes absent 1 (EYA1), LIM homeobox transcription factor 1 beta (LMX1B), and v-maf avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog (MAF) [11,16-18].

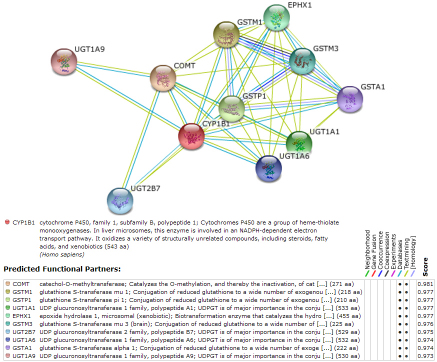

We next identified highly predicted functional partners of the target genes listed above using the Search Tool for Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins database (STRING, version 8.3), and we determined if any CNVs were associated with these genes (Table 2). The STRING database comprises known and predicted protein interactions, including direct (physical) and indirect (functional) associations; these interactions are derived based on genomic context, high-throughput experiments, conserved co-expression, and previous knowledge. An example of the STRING 8.3 results for CYP1B1 is provided in Figure 2.

Table 2. Table of predicted functional partners of the CYP1B1, MYOC, LTBP2, PAX6, PITX2, PITX3, FOXC1, FOXE3, EYA1, LMX1B, and MAF genes by STRING 8.3.

| CYP1B1 | MYOC | LTBP2 | PAX6 | PITX2 | PITX3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

COMT |

OPTN |

LTB |

SIX3 |

CTNNB1 |

TH |

|

GSTM1 |

CYP1B1 |

TGFBI |

MITF |

SUCLG1 |

SLC6A3 |

|

GSTP1 |

WDR36 |

ZNF185 |

SOX2 |

LEF1 |

GDNF |

|

UGT1A1 |

SNCG |

ELN |

NEUROG2 |

FOXC1 |

NR4A2 |

|

EPHX1 |

FN1 |

LOXL1 |

SOX3 |

CCND2 |

MTA1 |

|

GSTM3 |

SERPINF1 |

MFAP2 |

IPO13 |

GIPC1 |

FOXE3 |

|

UGTB7 |

HRAS |

COMMD9 |

PKNPX1 |

RGS1 |

SLC18A2 |

|

UGT1A6 |

TMTC1 |

ESYT3 |

TRIM11 |

RGS2 |

SOX2 |

|

GSTA1 |

TIMP1 |

ACYP1 |

SHH |

RGS7 |

BDNF |

|

UGT1A9 |

OLFM3 |

|

GCG |

|

CHMP4B |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

FOXC1 |

FOXE3 |

EYA1 |

LMX1B |

MAF |

|

|

PITX2 |

GPR161 |

SIX1 |

NPHS2 |

MYB |

|

|

DLL4 |

SOX2 |

SIX2 |

WNT7A |

NPRL3 |

|

|

HEY2 |

SMAD4 |

DACH1 |

NPS |

NFE2 |

|

|

ALX4 |

PITX2 |

PAX2 |

COL4A4 |

IL4 |

|

|

MSX2 |

FOXF2 |

GDNF |

PRODH2 |

ANPEP |

|

|

PAX6 |

FOXH1 |

SIX5 |

GPM6A |

BACH2 |

|

|

FGF2 |

SMAD2 |

PAX1 |

COK4A3 |

IRF4 |

|

|

FLNA |

HDAC9 |

TLX1 |

FOXA2 |

WHSC1 |

|

|

CYP1B1 |

POU5F1 |

MYOG |

LDB1 |

NFATC1 |

|

| CXCR4 | RSRFR2 | PAX3 | LRP6 |

Figure 2.

Evidence view of predicted functional partners of the CYP1B gene by STRING 8.3. Different line colors represent the types of evidence used to identify the associations.

Results

We performed aCGH to detect rare CNVs in PCG patients that were not present in 99 healthy controls. We identified 12 patients with at least one rare gene-containing deletion or duplication, corresponding to 25 CNVs (5 deletions and 20 duplications) at frequencies of 5%–30% in PCG patients and 0% in the controls (Table 3). According to the literature, most CNVs have a Mendelian inheritance pattern [19,20]. Therefore, we performed aCGH using parent-offspring trios, because the use of family information can improve the sensitivity and specificity of CNV detection. We matched 25 CNVs against the parents’ CNVs, which were classified into three main categories: loss of 1 copy from one parent (5 CNVs), gain of 1 copy from one parent (9 CNVs), and gain of 1 copy from de novo variation (6 CNVs). The remaining 5 CNVs were classified as ‘other’. No CNV was transmitted in an autosomal recessive inheritance manner. Considering that both parents of all patients were unaffected, loss or gain of one copy from only one parent is not likely to be associated with the disease phenotype. Only the gain of one copy due to de novo variation may represent an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance.

Table 3. Summary of 25 copy number variants in primary congenital glaucoma patients after the exclusion of known CNVs in the Database of Genomic Variants and the CNVs identified in 99 healthy controls.

| Case number | Frequency in case (%) | Chromosome location | Chromosome region | Size (bp) | CNV | Mode of inheritance* | Candidate gene(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 |

5.0 |

1p34.2 |

chr1:40,750,196–40,755,665 |

5470 |

loss of 1 copy |

P |

DEM1 |

| 16 |

5.0 |

8q22.1 |

chr8:95,459,849–95,465,598 |

5750 |

loss of 1 copy |

M |

RAD54B |

| 7 |

5.0 |

12q24.33 |

chr12:131,802,886–131,811,641 |

8756 |

loss of 1 copy |

P |

PGAM5 |

| 6 |

5.0 |

15q21.2 |

chr15:50,254,727–50,267,146 |

12420 |

loss of 1 copy |

P |

GNB5 |

| 5 |

5.0 |

15q25.2 |

chr15:82,494,744–82,501,742 |

6999 |

loss of 1 copy |

P |

ADAMTSL3 |

| 5 |

5.0 |

1p33 |

chr1:47,463,023–47,466,352 |

3330 |

gain of 1 copy |

D |

TAL1 |

| 5, 11, 18 |

15.0 |

2p11.2 |

chr2:85,213,649–85,217,093 |

3445 |

gain of 1 copy |

M, P/M, P |

TCF7L1 |

| 15 |

5.0 |

2q24.1 |

chr2:158,089,932–158,132,486 |

42555 |

gain of 1 copy |

P |

ACVR1C |

| 5 |

5.0 |

2q35 |

chr2:220,201,756–220,202,851 |

1096 |

gain of 1 copy |

D |

SLC4A3 |

| 5, 13 |

10.0 |

2q37.3 |

chr2:241,804,281–241,806,159 |

1878 |

gain of 1 copy |

M, M |

ANO7 |

| 18 |

5.0 |

6q14.1 |

chr6:79,840,645–79,848,461 |

7817 |

gain of 1 copy |

P |

PHIP |

| 12, 13 |

10.0 |

7q32.1 |

chr7:127,456,885–127,463,642 |

6758 |

gain of 1 copy† |

P, D |

LRRC4, SND1 |

| 11, 12, 13, 14, 18 |

25.0 |

8q12.1 |

chr8:56,176,574–56,182,718 |

6145 |

gain of 1 copy† |

P/M, M, D, D, P |

XKR4 |

| 5 |

5.0 |

8q21.13 |

chr8:80,840,460–80,844,589 |

4130 |

gain of 1 copy |

M |

HEY1 |

| 5, 18 |

10.0 |

9q22.31 |

chr9:95,251,169–95,254,542 |

7827 |

gain of 1 copy† |

M, D |

FAM120A, FAM120AOS |

| 3, 5, 10, 12, 13, 18 |

30.0 |

10q23.32 |

chr10:93,759,766–93,763,644 |

3879 |

gain of 1 copy† |

P/M, M, D, M, M, D |

BTAF1 |

| 3, 7, 12, 18 |

20.0 |

10q25.2 |

chr10:114,698,416–114,703,429 |

5014 |

gain of 1 copy |

P/M, P, P/M, P |

TCF7L2 |

| 5, 18 |

10.0 |

11q13.1 |

chr11:65,566,989–65,568,791 |

1803 |

gain of 1 copy† |

M, D |

GAL3ST3 |

| 12 |

5.0 |

11q13.1 |

chr11:65,868,765–65,875,077 |

6313 |

gain of 1 copy |

M |

B3GNT1, BRMS1 |

| 5 |

5.0 |

11q13.5 |

chr11:75,048,530–75,057,153 |

8624 |

gain of 1 copy |

D |

MAP6 |

| 7, 12, 18 |

15.0 |

11q23.3 |

chr11:120,535,111–120,539,731 |

4621 |

gain of 1 copy |

M, M, M |

TECTA |

| 6, 12, 18 |

15.0 |

13q12.13 |

chr13:26,231,092–26,233,822 |

2731 |

gain of 1 copy |

P, P/M, P/M |

GPR12 |

| 14 |

5.0 |

16q21 |

chr16:56,778,172–56,788,677 |

10506 |

gain of 1 copy |

D |

CSNK2A2 |

| 12 |

5.0 |

16q23.1 |

chr16:73,587,930–73,593,272 |

5343 |

gain of 1 copy |

D |

ZNRF1 |

| 14 | 5.0 | 18q11.2 | chr18:18,002,304–18,005,451 | 3148 | gain of 1 copy | D | GATA6 |

Abbreviation: P, paternal; M, maternal; P/M, paternal or maternal; D, de novo. * Mode of inheritance is placed in order of case number. † Gain of one copy from one parent and gain of one copy de novo.

We found that the 25 CNVs, identified within 28 genes, were not located in known chromosomal loci for PCG, namely GLC3A (2p2-p21), GLC3B (1p36.2-p36.1), or GLC3C (14q23). These CNVs did not include any target genes associated with PCG or ASD, nor the predicted functional partners of the target genes, and none of the genes had a specific gene function that appeared to be relevant to the pathogenesis of PCG (Table 3).

These 25 identified CNVs might be PCG-specific pathogenic variants or may represent extremely rare benign variants that are not associated with the disease. Further genetic strategies to validate these CNVs are needed to identify specific gene functions relevant to the pathogenesis of PCG.

Discussion

In this study, we performed aCGH in a series of 20 individuals diagnosed with PCG to discover novel copy number variations associated with this disease.

First, we chose target genes by expanding the disease spectrum of PCG to ASD, resulting in inclusion of the following target genes: CYP1B1, MYOC, LTBP2, PAX6, PITX2, PITX3, FOXC1, FOXE3, EYA1, LMX1B, and MAF [11,16-18]. Unlike PCG, ASD is classified into different subtypes according to the features of malformation affecting the anterior segment structure, e.g., aniridia, Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome, iridogoniodysgenesis, Peters’ anomaly, or posterior embryotoxon. However, some authors have claimed that PCG also involves abnormal development of Schlemm’s canal and trabecular meshwork drainage structures. Surprisingly, mutations in the ASD genes sometimes cause PCG, and PCG genes can also cause ASD [21,22]. In addition, dysregulation or mutation of a few ocular genes can cause a range of clinical conditions. For example, PAX6 was first identified as the gene for aniridia, but is now known to underlie a range of other ocular conditions including Peters’ anomaly and a rare case of ASD [23-25]. PITX2 and FOXC1 mutations have been found in Peters’ anomaly as well as PCG [26-28]. Peters’ anomaly is also associated with mutations in two other genes, CYP1B1 and the FOXC1-related gene, FOXE3 [29]. Therefore, we hypothesized that PCG may be considered part of the ASD spectrum; common genetic pathways may underlie these two disorders.

We explored other genetic mechanisms underlying PCG by gene dosage analysis, because previous CYP1B1 gene mutation studies have been unable to explain the allelic heterogeneity and pathogenesis of PCG in all patients. Previously, Kim et al. [10] performed direct sequencing analysis of all coding exons and flanking intronic regions of CYP1B1 and MYOC in 85 Korean patients with PCG. These authors reported that about 70% of Korean PCG patients have neither CYP1B1 nor MYOC mutations (CYP1B1 mutation rate, 25.9%; MYOC mutation rate, 2.4%), results consistent with those reported for Japanese and Chinese patients. Indeed, 12 out of 22 patients had only one mutant allele in the CYP1B1 gene [10]. In addition, the eye is known to be exquisitely sensitive to both reduced and increased gene dosage of key developmental genes. For example, gene dosage effects have been observed for PAX6 and FOXC1 in developmental ocular anomalies and ASD, respectively [12-15].

Overall, although we identified 25 CNVs (5 deletions and 20 duplications) in 12 PCG patients, we were unable to correlate these CNVs with the pathogenesis of PCG using a reference-based approach. The identified CNVs were not located in known chromosomal loci for PCG, namely GLC3A harboring CYP1B1 (2p21), GLC3B (1p36.2-p36.1), or GLC3C (14q23), and did not include any target genes associated with PCG and ASD, nor highly predicted functional partners of target genes. However, our data suggest that altered gene dosage may explain the disease pathogenesis in PCG if these CNVs are PCG-specific pathogenic variants.

Our study has some limitations. We were unable to exclude the existence of pathogenic variants that were too small to be detected using our platform (<500 bp). Despite the high genomic resolution of aCGH used in our study, some genomic regions might not be covered well or may not have been assessed due to technical difficulties. Furthermore, we did not perform further studies to determine the gene functions or expression levels of the CNVs we identified.

In conclusion, this is the first study to comprehensively investigate gene dosage effects in PCG. We believe that the preliminary results and the CNV filtering strategy that we used can broaden our understanding of the genetic mechanisms underlying PCG.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the following physicians for their help collecting samples from patients and their family members: Chan Yun Kim (Department of Ophthalmology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea), Ki Ho Park (Department of Ophthalmology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea), Michael S. Kook (Department of Ophthalmology, University of Ulsan, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea), Yong Yeon Kim (Department of Ophthalmology, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea), Chang Sik Kim (Department of Ophthalmology, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejon, Republic of Korea), and Chan Kee Park (Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea). This research was supported by The Center for Genome Research, Samsung Biomedical Research Institute.

References

- 1.Sarfarazi M, Stoilov I. Molecular genetics of primary congenital glaucoma. Eye (Lond) 2000;14(Pt 3B):422–8. doi: 10.1038/eye.2000.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakrabarti S, Ghanekar Y, Kaur K, Kaur I, Mandal AK, Rao KN, Parikh RS, Thomas R, Majumder PP. A polymorphism in the CYP1B1 promoter is functionally associated with primary congenital glaucoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4083–90. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarfarazi M, Akarsu AN, Hossain A, Turacli ME, Aktan SG, Barsoum-Homsy M, Chevrette L, Sayli BS. Assignment of a locus (GLC3A) for primary congenital glaucoma (Buphthalmos) to 2p21 and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Genomics. 1995;30:171–7. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoilov I, Sarfarazi M. The third genetic locus (GLC3C) for primary congenital claucoma (PCG) maps to chromosome 14q24.3. ARVO Annual Meeting; 2002 May 5-20; Fort Lauderdale (FL). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akarsu AN, Turacli ME, Aktan SG, Barsoum-Homsy M, Chevrette L, Sayli BS, Sarfarazi M. A second locus (GLC3B) for primary congenital glaucoma (Buphthalmos) maps to the 1p36 region. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1199–203. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.8.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plásilová M, Stoilov I, Sarfarazi M, Kadasi L, Ferakova E, Ferak V. Identification of a single ancestral CYP1B1 mutation in Slovak Gypsies (Roms) affected with primary congenital glaucoma. J Med Genet. 1999;36:290–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zenteno JC, Hernandez-Merino E, Mejia-Lopez H, Matias-Florentino M, Michel N, Elizondo-Olascoaga C, Korder-Ortega V, Casab-Rueda H, Garcia-Ortiz JE. Contribution of CYP1B1 mutations and founder effect to primary congenital glaucoma in Mexico. J Glaucoma. 2008;17:189–92. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31815678c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Jiang D, Yu L, Katz B, Zhang K, Wan B, Sun X. CYP1B1 and MYOC mutations in 116 Chinese patients with primary congenital glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1443–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.10.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mashima Y, Suzuki Y, Sergeev Y, Ohtake Y, Tanino T, Kimura I, Miyata H, Aihara M, Tanihara H, Inatani M, Azuma N, Iwata T, Araie M. Novel cytochrome P4501B1 (CYP1B1) gene mutations in Japanese patients with primary congenital glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HJ, Suh W, Park SC, Kim CY, Park KH, Kook MS, Kim YY, Kim CS, Park CK, Ki CS, Kee C. Mutation spectrum of CYP1B1 and MYOC genes in Korean patients with primary congenital glaucoma. Mol Vis. 2011;17:2093–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sowden JC. Molecular and developmental mechanisms of anterior segment dysgenesis. Eye (Lond) 2007;21:1310–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schedl A, Ross A, Lee M, Engelkamp D, Rashbass P, van Heyningen V, Hastie ND. Influence of PAX6 gene dosage on development: overexpression causes severe eye abnormalities. Cell. 1996;86:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser T, Jepeal L, Edwards JG, Young SR, Favor J, Maas RL. PAX6 gene dosage effect in a family with congenital cataracts, aniridia, anophthalmia and central nervous system defects. Nat Genet. 1994;7:463–71. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aalfs CM, Fantes JA, Wenniger-Prick LJ, Sluijter S, Hennekam RC, van Heyningen V, Hoovers JM. Tandem duplication of 11p12-p13 in a child with borderline development delay and eye abnormalities: dose effect of the PAX6 gene product? Am J Med Genet. 1997;73:267–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19971219)73:3<267::aid-ajmg7>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehmann OJ, Ebenezer ND, Jordan T, Fox M, Ocaka L, Payne A, Leroy BP, Clark BJ, Hitchings RA, Povey S, Khaw PT, Bhattacharya SS. Chromosomal duplication involving the forkhead transcription factor gene FOXC1 causes iris hypoplasia and glaucoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:1129–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9297(07)62943-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanwar M, Kumar M, Dada T, Sihota R, Dada R. MYOC and FOXC1 gene analysis in primary congenital glaucoma. Mol Vis. 2010;16:1996–2006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali M, McKibbin M, Booth A, Parry DA, Jain P, Riazuddin SA, Hejtmancik JF, Khan SN, Firasat S, Shires M, Gilmour DF, Towns K, Murphy AL, Azmanov D, Tournev I, Cherninkova S, Jafri H, Raashid Y, Toomes C, Craig J, Mackey DA, Kalaydjieva L, Riazuddin S, Inglehearn CF. Null mutations in LTBP2 cause primary congenital glaucoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:664–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith RS, Zabaleta A, Kume T, Savinova OV, Kidson SH, Martin JE, Nishimura DY, Alward WL, Hogan BL, John SW. Haploinsufficiency of the transcription factors FOXC1 and FOXC2 results in aberrant ocular development. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1021–32. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.7.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang K, Chen Z, Tadesse MG, Glessner J, Grant SF, Hakonarson H, Bucan M, Li M. Modeling genetic inheritance of copy number variations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e138. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Locke DP, Sharp AJ, McCarroll SA, McGrath SD, Newman TL, Cheng Z, Schwartz S, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Altshuler DM, Eichler EE. Linkage disequilibrium and heritability of copy-number polymorphisms within duplicated regions of the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:275–90. doi: 10.1086/505653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gould DB, John SW. Anterior segment dysgenesis and the developmental glaucomas are complex traits. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1185–93. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.10.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vincent A, Billingsley G, Priston M, Williams-Lyn D, Sutherland J, Glaser T, Oliver E, Walter MA, Heathcote G, Levin A, Heon E. Phenotypic heterogeneity of CYP1B1: mutations in a patient with Peters' anomaly. J Med Genet. 2001;38:324–6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.5.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riise R, D'Haene B, De Baere E, Gronskov K, Brondum-Nielsen K. Rieger syndrome is not associated with PAX6 deletion: a correction to Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2001: 79: 201–203. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:923. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nanjo Y, Kawasaki S, Mori K, Sotozono C, Inatomi T, Kinoshita S. A novel mutation in the alternative splice region of the PAX6 gene in a patient with Peters' anomaly. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:720–1. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.034769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanson IM, Fletcher JM, Jordan T, Brown A, Taylor D, Adams RJ, Punnett HH, van Heyningen V. Mutations at the PAX6 locus are found in heterogeneous anterior segment malformations including Peters' anomaly. Nat Genet. 1994;6:168–73. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishimura DY, Swiderski RE, Alward WL, Searby CC, Patil SR, Bennet SR, Kanis AB, Gastier JM, Stone EM, Sheffield VC. The forkhead transcription factor gene FKHL7 is responsible for glaucoma phenotypes which map to 6p25. Nat Genet. 1998;19:140–7. doi: 10.1038/493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honkanen RA, Nishimura DY, Swiderski RE, Bennett SR, Hong S, Kwon YH, Stone EM, Sheffield VC, Alward WL. A family with Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome and Peters Anomaly caused by a point mutation (Phe112Ser) in the FOXC1 gene. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:368–75. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perveen R, Lloyd IC, Clayton-Smith J, Churchill A, van Heyningen V, Hanson I, Taylor D, McKeown C, Super M, Kerr B, Winter R, Black GC. Phenotypic variability and asymmetry of Rieger syndrome associated with PITX2 mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2456–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edward D, Al Rajhi A, Lewis RA, Curry S, Wang Z, Bejjani B. Molecular basis of Peters anomaly in Saudi Arabia. Ophthalmic Genet. 2004;25:257–70. doi: 10.1080/13816810490902648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]