Abstract

BACKGROUND

Information comparing characteristics of patients who do and do not pick up their prescriptions is sparse, in part because adherence measured using pharmacy claims databases does not include information on patients who never pick up their first prescription, that is, patients with primary non-adherence. Electronic health record medication order entry enhances the potential to identify patients with primary non-adherence, and in organizations with medication order entry and pharmacy information systems, orders can be linked to dispensings to identify primarily non-adherent patients.

OBJECTIVE

This study aims to use database information from an integrated system to compare patient, prescriber, and payment characteristics of patients with primary non-adherence and patients with ongoing dispensings of newly initiated medications for hypertension, diabetes, and/or hyperlipidemia.

DESIGN

This is a retrospective observational cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS (OR PATIENTS OR SUBJECTS)

Participants of this study include patients with a newly initiated order for an antihypertensive, antidiabetic, and/or antihyperlipidemic within an 18-month period.

MAIN MEASURES

Proportion of patients with primary non-adherence overall and by therapeutic class subgroup. Multivariable logistic regression modeling was used to investigate characteristics associated with primary non-adherence relative to ongoing dispensings.

KEY RESULTS

The proportion of primarily non-adherent patients varied by therapeutic class, including 7% of patients ordered an antihypertensive, 11% ordered an antidiabetic, 13% ordered an antihyperlipidemic, and 5% ordered medications from more than one of these therapeutic classes within the study period. Characteristics of patients with primary non-adherence varied across therapeutic classes, but these characteristics had poor ability to explain or predict primary non-adherence (models c-statistics = 0.61–0.63).

CONCLUSIONS

Primary non-adherence varies by therapeutic class. Healthcare delivery systems should pursue linking medication orders with dispensings to identify primarily non-adherent patients. We encourage conduct of research to determine interventions successful at decreasing primary non-adherence, as characteristics available from databases provide little assistance in predicting primary non-adherence.

KEY WORDS: medication adherence, primary non-adherence, antihypertensive adherence, antidiabetic adherence, antihyperlipidemic adherence

INTRODUCTION

Adherence to medications is directly associated with improved clinical outcomes, higher quality of life, and lower healthcare costs across many chronic conditions.1–8 A substantial portion of adherence literature is based on estimates obtained from pharmacy claims databases, in part because such databases are a relatively inexpensive and accessible tool for obtaining medication refill data across large populations.1,2 A limitation to the use of pharmacy claims is that adherence can only be estimated for patients who have purchased the drug (i.e., have an insurance claim).2,9

Primary non-adherence, defined as not having picked up the initial prescription, is infrequently calculated and has only recently begun to be examined from a population perspective.9–14 Patients with primary non-adherence are by definition excluded from adherence estimates derived from pharmacy claims because a claim indicates the drug was purchased. Identifying patients with primary non-adherence requires reconciliation and linkage of prescription orders and medication dispensings. Unfortunately, linkages between orders and dispensings were rare until recently—and still remain uncommon—because most prescription ordering and medication dispensing systems are separate systems lacking an electronic interface.

Medication order entry within electronic health records (EHR) has enhanced the potential to identify patients with primary non-adherence.10,12,14 Further, within integrated systems where EHR prescription order entry, pharmacy information systems, and dispensing pharmacies are routinely used, prescriptions ordered through the EHR can be more readily linked to dispensing data to ascertain whether a prescription order was ever sold to the patient.12,15

Given the difficulty in identifying primary non-adherence, little population-based research has been conducted to characterize patients with primary non-adherence. Further, little is known about similarities or differences between patients with primary non-adherence and those with ongoing dispensings defined as patients who pick up at least two dispensings of a medication intended for chronic use. Finally, it is not clear whether characterizing primarily non-adherent patients will be useful in explaining non-adherence behaviors. Our objective was to use information from clinical and administrative databases within an integrated delivery system to characterize and compare patient, prescriber, and payment characteristics between individuals with primary non-adherence and individuals with ongoing dispensings to newly initiated oral medications for hypertension, diabetes, and/or hyperlipidemia.

METHODS

Study Setting and Population

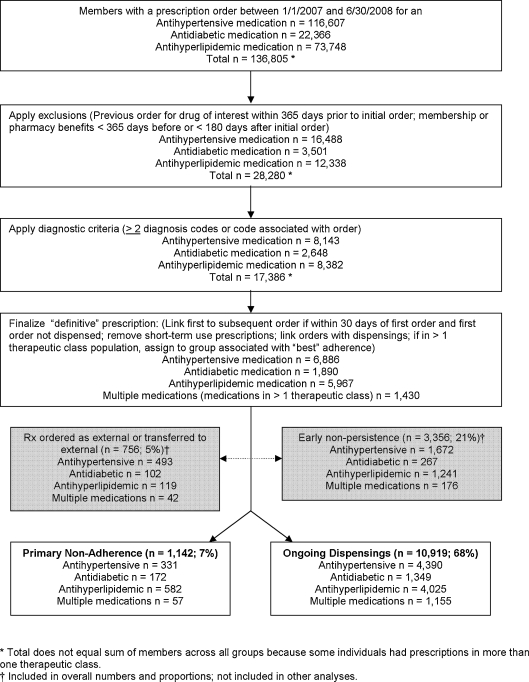

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Kaiser Permanent Colorado (KPCO), an integrated healthcare delivery system in the Denver-Boulder area. The study cohort included all KPCO members with a newly initiated order for an antihypertensive, antidiabetic, or antihyperlipidemic medication between 1 January 2007 and 30 June 2008 (Fig. 1). Cohort members were required to have no previous order for a drug in the same therapeutic class within 365 days prior to the initial order during the study period, and were required to be a KPCO member with a pharmacy benefit for at least 365 days before and 180 days after the initial order. Individuals were also required to have at least two coded diagnoses at least 1 month apart that corresponded to the medication (antihypertensive medication, ICD9 codes for hypertension 401.0–405.9; antidiabetic medication, ICD9 codes for diabetes 250.##; antihyperlipidemic medication, ICD9 codes for hyperlipidemia 272.##) or to have the corresponding diagnosis associated with the prescription order within the EHR order entry module. This study was approved by the KPCO Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Selection of primary non-adherence and ongoing dispensings cohorts.

Medication Orders and Dispensings

Index, or new, prescription orders were identified from the EHR. To determine the “definitive” index order, we linked the first order to any subsequent, revised order if a revised order was entered within 30 days of the initial order and before the initial order was dispensed.15 Prescriptions clearly not intended for chronic use were excluded (e.g., peri-operative beta-blocker prescriptions for <30 total days).

Orders dispensed at a KPCO pharmacy are routed to the pharmacy information management system (PIMS) using an established electronic interface. We determined from PIMS whether and when the medication was dispensed. Orders and dispensings were linked using unique patient identifier, dispense date, and Generic Product Identifier (GPI; Medi-Span; licensed through McKesson, San Francisco, CA).

For drug identification, a comprehensive listing within each therapeutic class was assembled through a look-up table cross-referenced by national drug code (NDC) and by GPI. For all dispensings, the initial and refill dates, strength, formulation, instructions for use, days’ supply, prescriber identifier and department, and NDC were ascertained.

Primary Non-adherence and Ongoing Dispensing Assessment

Patients were stratified into patient-drug adherence groups based on the following definitions:

Primary non-adherence: Did not pick up the prescription (i.e., medication not dispensed to patient) for the newly initiated medication at a KPCO pharmacy and did not have it transferred to a pharmacy external to KPCO within 30 days after the order.

Ongoing dispensing: Picked up the prescription (i.e., medication dispensed to patient) for the newly initiated chronic medication at a KPCO pharmacy and had the prescription refilled at least once at a KPCO pharmacy within 180 days after initial dispensing (i.e., at least two dispensings).

For completeness, prescriptions ordered for patients who subsequently had just one dispensing of a chronic medication but no refills within 180 days (defined as patients with early non-persistence) and prescriptions ordered for dispensing external to KPCO were quantified and included in the total number of patients with orders, but were not otherwise included in this study (Fig. 1). Early non-persistent patients were excluded because they can differ substantively (e.g., discontinuation due to adverse events) from patients with primary non-adherence or ongoing dispensings.

We further categorized patients with primary non-adherence or ongoing dispensings into therapeutic class subgroups (antihypertensive, antihyperlipidemic, and antidiabetic). Patients with new orders for drugs from two or three of these therapeutic classes that were all initiated within the 18-month study timeframe (e.g., new orders for both an antihyperlipidemic and an antihypertensive during the 18-month period) were assigned to a “multiple medications” subgroup.

If patients in the multiple medications subgroup met criteria for ongoing dispensings for any of the newly initiated medications, they were classified as having ongoing dispensings. That is, these patients had to have primary non-adherence to all newly initiated medications within the study therapeutic classes to be assigned to the primary non-adherence group. All groups and subgroups were mutually exclusive.

Adherence was calculated using the proportion of days covered (PDC) method. This measure reports medication availability by estimating the proportion of prescribed days supply obtained during a specified time period over refill intervals.9,16 To obtain the PDC, the total days’ supply dispensed is divided by number of days in the observation period. This number is capped at 1 and multiplied by 100 to obtain % adherence.

Patient, Utilization, Prescriber, and Payment Characteristics

We identified potential variables of interest based on prior adherence literature and included variables from the sociodemographic, enrollment, utilization, benefits, and prescriber characteristics and clinical conditions readily available from the databases of our integrated system. We collected patient demographic, enrollment, and clinical information including age, gender, race/ethnicity, number of comorbidities (Quan modification of the Elixhauser algorithm),17 smoking status, obesity (determined from BMI), socioeconomic status (SES, defined as low if at least 20% of residents in a person’s residence block had household incomes below the federal poverty level or at least 25% of residents aged 25 or older in the census block had less than a high school education), length of health plan enrollment, number of unique dispensed medications overall, and a depression diagnosis within 6 months prior to the index order. We collected information about insurance/benefits, utilization, outpatient visit copayment/coinsurance, pharmacy copayment/cost sharing, and number of ambulatory health care contacts (clinic visits, phone calls, and emails) within the 6 months before and after the index order. We also identified the ordering prescriber type and department.

Validation of Definitive Medication Order Date

We conducted medical record review on a random sample of study patients newly prescribed antidiabetic (n = 50) or antihypertensive (n = 50) medications to identify any systematic problems with the preliminary computer programming used to determine definitive order date. For example, we learned that the order date field was overridden by the most recent refill of that order. This record review was instrumental in refining the programming code to accurately group patients into adherence groups.15

Data Sources, Management, and Statistical Analysis

Existing databases, the PIMS, and the ambulatory EHR were used to ascertain all study data. We examined the distributions of variables to ensure they met the assumptions of the statistical tests employed. The groups were then compared overall and by therapeutic class subgroups. Differences in characteristics were assessed using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test for continuous variables.

Multivariable logistic regression modeling was performed to investigate characteristics associated with the likelihood of primary non-adherence relative to ongoing dispensing. Prior to constructing models, variables were examined for multi-collinearity. Two separate models were constructed for each therapeutic class subgroup. The first contained only the patient demographic, enrollment and clinical characteristics. The second contained all variables. The discrimination of these models was evaluated using the c-statistic, with a greater c-statistic reflecting greater discrimination. All data checks and analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1.3.

RESULTS

We identified 16,173 patients with a newly ordered prescription for an antihypertensive, antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, or for multiple medications during the study period, including 12,061 patients of interest for this study: 1,142 with primary non-adherence and 10,919 with ongoing dispensings (Fig. 1; Table 1). There were 4,721 patients with a newly ordered medication for hypertension, 4,607 for hyperlipidemia, 1,521 for diabetes, and 1,212 with multiple medications. Because the proportions of patients with primary non-adherence varied among the therapeutic classes (p < 0.001) (Tables 1 and 2), further analysis was conducted with patients stratified by therapeutic class. Primary non-adherence was observed among 331 (7%) patients with an antihypertensive, 582 (13%) patients with an antihyperlipidemic, 172 (11%) patients with an antidiabetic, and 57 (5%) patients with two or three of these medications. Differences between individuals with primary non-adherence and those with ongoing dispensings are shown in Table 2. Because only 57 multiple medications subgroup patients exhibited primary non-adherence (multiple medications subgroup patients were required to be primarily non-adherent to all newly initiated medications to be classified as primarily non-adherent), data for these patients are not shown in Table 2, and this small subgroup was not included in logistic regression analysis.

Table 1.

Overall Characteristics of Patients with Primary Non-adherence and Ongoing Dispensings

| Characteristic | Adherence group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary (n = 1,142) | Ongoing (n = 10,919) | ||

| Demographic and enrollment characteristics | |||

| Age in years (mean (SD)) | 58.9 (13.5) | 59.3 (13.3) | 0.45 |

| Male gender (n (%)) | 593 (51.9) | 5,462 (50.0) | 0.22 |

| Race (n (%)) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 571 (50.0) | 6,277 (57.5) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 161 (14.1) | 1,147 (10.5) | |

| Other | 111 (9.7) | 884 (8.1) | |

| Unknown | 299 (26.2) | 2,611 (23.9) | |

| Smoking status (n (%))* | |||

| Smoker | 195 (17.1) | 1,566 (14.3) | 0.01 |

| Other tobacco | 5 (0.4) | 55 (0.5) | |

| Non-smoker | 936 (82.0) | 9,277 (85.0) | |

| Unknown | 6 (0.5) | 21 (0.2) | |

| Low SES (n (%)) | 188 (16.5) | 1,384 (12.7) | <0.001 |

| Cumulative length of enrollment in years (mean (SD)) | 10.6 (4.5) | 11.1 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Therapeutic class subgroup (n (%)) | |||

| Antidiabetic | 172 (15.1) | 1,349 (12.4) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive | 331 (29.0) | 4,390 (40.2) | |

| Antihyperlipidemic | 582 (51.0) | 4,025 (36.9) | |

| Multiple | 57 (5.0) | 1,155 (10.6) | |

| Quan comorbidity score (mean (SD)) | 1.6 (1.8) | 1.4 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Depression diagnosis within 6 months prior to order (n (%)) | 115 (10.1) | 1,070 (9.8) | 0.77 |

| Unique number of medications (mean (SD)) | 3.7 (3.5) | 4.8 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| BMI (mean (SD)) | 30.2 (6.6) | 30.5 (6.7) | 0.32 |

| Utilization, benefits, and insurance | |||

| Outpatient clinic visit, phone calls and emails within 6 months prior to index date (mean (SD)) | 5.8 (5.8) | 5.6 (5.5) | 0.07 |

| Outpatient clinic visits, phone calls and emails within 6 months after index date (mean (SD)) | 7.1 (6.8) | 7.9 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Insurance product (n (%)) | |||

| HMO | 1,030 (90.2) | 10,041(92.0) | 0.04 |

| Deductible/coinsurance | 64 (5.6) | 557 (5.1) | |

| Other | 48 (4.2) | 321 (2.9) | |

| Pharmacy copayment/coinsurance (n (%))† | |||

| $1–10 copayment | 665 (58.2) | 6,586 (60.3) | 0.22 |

| $15 copayment | 436 (38.2) | 4,018 (36.8) | |

| $20–25 copayment/coinsurance/others | 41 (3.6) | 315 (2.9) | |

| Office visit copayment/coinsurance | |||

| $0–10 copayment | 264 (23.1) | 2,748 (25.2) | 0.14 |

| $11–20 copayment | 153 (13.4) | 1,609 (14.7) | |

| > $20 copayment | 299 (26.2) | 2,797 (25.6) | |

| Coinsurance | 426 (37.3) | 3,765 (34.5) | |

| Adherence | |||

| Proportion of days covered (PDC) (180 days mean (SD))‡ | |||

| Overall | 0.19 (0.25) | 0.84 (0.19) | <0.001 |

| Antidiabetic | 0.14 (0.24) | 0.86 (0.19) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive | 0.13 (0.22) | 0.84 (0.20) | <0.001 |

| Antihyperlipidemic | 0.25 (0.26) | 0.84 (0.18) | <0.001 |

| Prescriber characteristics | |||

| Ordering prescriber type (n (%))§ | |||

| Primary care | 1,063 (93.1) | 9,973 (91.3) | <0.001 |

| Specialty care | 26 (2.3) | 312 (2.9) | |

| Population management | 22 (1.9) | 96 (0.9) | |

| Urgent care/ED/hosp | 4 (0.4) | 198 (1.8) | |

| Unknown/admin | 27 (2.4) | 340 (3.1) | |

| Ordering prescriber departtment (n (%)) | |||

| Primary care | 1,063 (93.1) | 9,973 (91.3) | 0.04 |

| Non-primary care | 79 (6.9) | 946 (8.7) | |

*Measurement date closest to index date

†Generic copayment/coinsurance structure shown because drug initiations were with generic agents

‡The PDC is not 0 for all those in the primary non-adherence group because a small proportion of these individuals eventually had the prescription filled at some time point after 30 days but before 180 days after the order

§Clinical pharmacy specialist or nurse as well as physician or physician assistant

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients with Primary Non-adherence and with Ongoing Dispensings by Therapeutic Class Subgroups

| Characteristic (n (%)) | Antidiabetic | Antihypertensive | Antihyperlipidemic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Ongoing | p value* | Primary | Ongoing | p value* | Primary | Ongoing | p value* | |

| n = 172 (11%) | n = 1,349 (89%) | n = 331 (7%) | n = 4,390 (93%) | n = 582 (13%) | n = 4,025 (87%) | ||||

| Demographic and enrollment characteristics | |||||||||

| Age group | |||||||||

| ≤49 | 38 (22) | 253 (19) | 0.42 | 96 (29) | 1,316 (30) | 0.81 | 116 (20) | 680 (17) | 0.01 |

| 50–64 | 70 (41) | 532 (39) | 131 (40) | 1,768 (40) | 264 (45) | 1,693 (42) | |||

| 65+ | 64 (37) | 564 (42) | 104 (31) | 1,306 (30) | 202 (35) | 1,652 (41) | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 86 (50) | 637 (47) | 0.49 | 161 (49) | 2,288 (52) | 0.22 | 283 (49) | 2,007 (50) | 0.58 |

| Male | 86 (50) | 712 (53) | 170 (51) | 2,102 (48) | 299 (51) | 2,018 (50) | |||

| Race | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 77 (45) | 720 (53) | 0.14 | 150 (45) | 2,530 (58) | <0.001 | 317 (54) | 2,430 (60) | <0.01 |

| Hispanic | 35 (20) | 211 (15) | 44 (13) | 424 (10) | 73 (13) | 335 (8) | |||

| Other | 21 (12) | 128 (10) | 39 (12) | 369 (8) | 42 (7) | 286 (7) | |||

| Missing/unknown | 39 (23) | 290 (22) | 98 (30) | 1,067 (24) | 150 (26) | 974 (24) | |||

| SES | |||||||||

| Low | 37 (22) | 213 (16) | 0.15 | 55 (17) | 534 (12) | 0.04 | 86 (15) | 461 (11) | 0.06 |

| Not low | 131 (76) | 1,094 (81) | 269 (81) | 3,712 (85) | 475 (82) | 3,432 (85) | |||

| Unknown/missing | 4 (2) | 42 (3) | 7 (2) | 198 (5) | 21 (4) | 132 (3) | |||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| No tobacco | 138 (80) | 1,174 (87) | 0.02 | 273 (82) | 3,688 (84) | 0.47 | 484 (83) | 3,489 (87) | 0.02 |

| Tobacco | 34 (20) | 175 (13) | 58 (18) | 702 (16) | 98 (17) | 536 (13) | |||

| Enrollment | |||||||||

| <10 years | 73 (42) | 503 (37) | 0.19 | 171 (52) | 1,984 (45) | 0.02 | 278 (48) | 1,704 (42) | 0.01 |

| 10+ years | 99 (58) | 846 (63) | 160 (48) | 2,406 (55) | 304 (52) | 2,321 (58) | |||

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||||

| Quan category | |||||||||

| 0 | 48 (28) | 331 (25) | 0.88 | 174 (53) | 2,496 (57) | 0.34 | 163 (28) | 1,108 (28) | 0.07 |

| 1 | 45 (26) | 356 (26) | 81 (24) | 1,032 (24) | 134 (23) | 1,106 (27) | |||

| 2 | 34 (20) | 279 (21) | 37 (11) | 455 (10) | 105 (18) | 767 (19) | |||

| 3 | 22 (13) | 174 (13) | 17 (5) | 210 (5) | 78 (13) | 459 (11) | |||

| 4+ | 23 (13) | 209 (16) | 22 (7) | 197 (4) | 102 (18) | 585 (15) | |||

| Obese (based on BMI) | |||||||||

| No | 56 (33) | 527 (39) | 0.16 | 188 (57) | 2,365 (54) | 0.02 | 334 (57) | 2,400 (60) | 0.42 |

| Yes | 113(66) | 810 (60) | 132 (40) | 1,958 (45) | 243 (42) | 1,603 (40) | |||

| Unknown/missing | 3 (2) | 12 (1) | 11 (3) | 67 (2) | 5 (1) | 22 (1) | |||

| Utilization, benefits, and insurance | |||||||||

| Office visits/phone/emails 6 months post-index order | |||||||||

| <5 | 70 (41) | 389 (29) | 0.001 | 153 (46) | 1,775 (40) | 0.04 | 258 (44) | 1,751 (44) | 0.71 |

| 5+ | 102 (59) | 960 (71) | 178 (54) | 2,615 (60) | 324 (56) | 2,274 (56) | |||

| Insurance product | |||||||||

| HMO | 162 (94) | 1,258 (93) | 0.69 | 289 (87) | 4,006 (91) | <0.001 | 525 (90) | 3,730 (93) | 0.10 |

| Deduct/coinsurance | 8 (5) | 62 (5) | 19 (6) | 259 (6) | 35 (6) | 173 (4) | |||

| Other | 2 (1) | 29 (2) | 23 (7) | 125 (3) | 22 (4) | 122 (3) | |||

| Office visit copayment | |||||||||

| $0–10 | 37 (22) | 369 (27) | 0.44 | 77 (23) | 1,007 (23) | 0.90 | 137 (24) | 1,129 (28) | 0.05 |

| $11–20 | 27 (16) | 191 (14) | 46 (14) | 679 (15) | 75 (13) | 571 (14) | |||

| >$20 | 44 (26) | 323 (24) | 91 (27) | 1,171 (27) | 150 (26) | 995 (25) | |||

| Coinsurance | 64 (37) | 466 (35) | 117 (35) | 1,533 (35) | 220 (38) | 1,330 (33) | |||

| Prescriber characteristics | |||||||||

| Ordering prescriber department | |||||||||

| Primary care | 158 (92) | 1,238 (92) | 0.97 | 300 (91) | 4,103 (93) | 0.05 | 553 (95) | 3,593 (89) | <0.001 |

| Non-primary care | 14 (8) | 111 (8) | 31 (9) | 287 (7) | 29 (5) | 43 (11) | |||

Characteristics that were not significant within any Therapeutic Class Subgroup are not shown

*Chi-square or Kruskal–Wallis test

In the adjusted model, patients with a newly ordered medication for diabetes who smoked tobacco were more likely to be primarily non-adherent (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.05, 2.49) and patients with five or more ambulatory healthcare contacts in the 6 months after the order were less likely to be primarily non-adherent (OR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.40, 0.82)(Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted Associations Between Characteristics of Patients with Primary Non-adherence Compared with Patients with Ongoing Dispensings by Therapeutic Class Subgroups

| Characteristic | Antidiabetic | Antihypertensive | Antihyperlipidemic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Age category (reference: 65+) | |||

| 50–64 | 0.87 (0.57, 1.34) | 0.83 (0.61, 1.14) | 1.22 (0.97, 1.55) |

| ≤49 | 0.88 (0.52, 1.50) | 0.77 (0.54, 1.10) | 1.28 (0.95, 1.72) |

| Race (reference: non-Hispanic White) | |||

| Hispanic | 1.33 (0.84, 2.10) | 1.74 (1.20, 2.52) | 1.47 (1.09, 1.97) |

| Other | 1.45 (0.85, 2.49) | 1.87 (1.28, 2.72) | 1.06 (0.75, 1.51) |

| Unknown/missing | 1.12 (0.73, 1.72) | 1.48 (1.13, 1.95) | 1.13 (0.91, 1.40) |

| SES (reference: not low) | |||

| Low | 1.30 (0.86, 1.98) | 1.30 (0.95, 1.79) | 1.23 (0.95, 1.60) |

| Missing | 0.86 (0.30, 2.47) | 0.66 (0.30, 1.43) | 1.17 (0.73, 1.88) |

| Tobacco (reference: no tobacco) | 1.63 (1.05, 2.49) | 1.08 (0.80, 1.47) | 1.26 (0.99, 1.60) |

| <10 year enrollment (reference: 10+) | 1.29 (0.91, 1.82) | 1.28 (1.00, 1.62) | 1.20 (1.00, 1.45) |

| Quan category (reference: 0) | |||

| 1 | 0.95 (0.60, 1.49) | 1.22 (0.91, 1.63) | 0.86 (0.67, 1.11) |

| 2 | 0.92 (0.71, 1.18) | 1.14 (0.93, 1.39) | 1.01 (0.88, 1.17) |

| 3 | 0.90 (0.50, 1.63) | 1.35 (0.77, 2.35) | 1.38 (1.00, 1.893) |

| 4+ | 0.84 (0.45, 1.59) | 1.76 (1.02, 3.02) | 1.59 (1.16, 2.19) |

| Obesity (reference: not obese) | |||

| Yes | 1.37 (0.95, 1.97) | 0.86 (0.67, 1.10) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.17) |

| Unknown/missing | 2.26 (0.58, 8.88) | 1.48 (0.74, 2.96) | 1.67 (0.61, 4.62) |

| 5+ office visits/phone/email contacts within 6 months after index date (reference: <5) | 0.58 (0.40, 0.82) | 0.77 (0.60, 0.98) | 1.01 (0.83, 1.22) |

| Insurance product (reference: HMO) | |||

| Deductible/coinsurance | 1.01 (0.45, 2.28) | 1.02 (0.61, 1.70) | 1.47 (0.97, 2.21) |

| Other | 0.41 (0.09, 1.96) | 2.56 (1.46, 4.50) | 1.32 (0.78, 2.23) |

| Ordering prescriber department non-primary care (reference: primary care) | 1.24 (0.63, 2.45) | 1.16 (0.74, 1.84) | 0.33 (0.21, 0.50) |

| c-statistic | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.61 |

Characteristics that were not significant within any Therapeutic Class Subgroup are not shown

In patients with a newly ordered medication for antihypertensive, those with race/ethnicity other than non-Hispanic white were more likely to be primarily non-adherent (Hispanic OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.20, 2.52 and other race/ethnicity, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.28, 2.72), as were those with shorter length of health plan enrollment (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.00, 1.62), and those enrolled in an insurance product other than traditional HMO (OR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.46, 4.50). Patients in the antihypertensive subgroup with more healthcare contacts in the 6 months after the index order were less likely to be primarily non-adherent (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.60, 0.98) and an association between four or more comorbidities and primary non-adherence (OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.02, 3.02) emerged.

In patients with newly ordered medication for hyperlipidemia, those of Hispanic ethnicity (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.09, 1.97), shorter health plan enrollment (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.00, 1.45), and three (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.00, 1.89) or four or more (OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 0.80, 1.42) comorbidities were more likely to be primarily non-adherent. Having the antihyperlipidemic prescribed by a provider in a non-primary care department was associated with a lower likelihood of primary non-adherence (OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.21, 0.50).

The characteristics included in the full models were of limited utility in discriminating between patients with primary non-adherence and patients with ongoing dispensings: antidiabetic model c-statistic = 0.62, antihypertensive = 0.63, and antihyperlipidemic = 0.61 (Table 3). The c-statistics of the models that contained only patient characteristics were similar: Antidiabetic model c-statistic = 0.60, antihypertensive = 0.61, and antihyperlipidemic = 0.58 (not shown in table).

DISCUSSION

In patients with a newly ordered medication for hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia, we documented that 7% were primarily non-adherent, that is, they did not have their prescription filled within 30 days after the order. The proportion of patients with primary non-adherence varied by therapeutic class with more primary non-adherence among those ordered an antihyperlipidemic and less among patients ordered an antihypertensive. While our work was not designed to compare characteristics associated with primary non-adherence across therapeutic classes, these results suggest that factors vary. The ability of the characteristics we assessed to predict primary non-adherence was poor, based on the discrimination of the regression models.

Karter and colleagues identified 5% primary non-adherence,12 while we identified 7% primary non-adherence. This difference is likely due to differences between definitions, as the Karter et al. definition was not filling the prescription within 60 days,12 while our definition was not filling the prescription within 30 days. Both our findings and those of Karter et al. differ markedly from those of Fischer and colleagues where a primary non-adherence rate of 22.5% was found.14 Fischer and colleagues compared prescription orders and filled claims between systems, whereas we directly linked orders to dispensings within one system. As Karter and colleagues pointed out, claims-based research is subject to misclassification because all dispensings not captured are considered not dispensed, yet there are other reasons for not capturing dispensings when cross-walking databases between non-integrated systems (e.g., cash prescriptions, out-of-plan dispensings).18 Thus, the primary non-adherence rate determined by Fischer et al. is likely overestimated. Two other studies using claims data found primary non-adherence of 15% and 17% for antidiabetics and antihypertensives, respectively).10,13

Numerous researchers have identified characteristics associated with refill adherence,19–30 but few have determined characteristics associated with primary non-adherence.10,13,31 We determined characteristics associated with an increased risk of primary non-adherence and identified differences by therapeutic indication, but found no strongly associated characteristics. The only OR >2 or <0.5 were “other” insurance products (OR, 2.56) for antihypertensives and prescribing by a non-primary care department (OR, 0.33) for antihyperlipidemics. Insurance products characterized as “others” are high deductible or triple option in our system; this association could reflect a particular patient-employer subset. At KPCO, antihyperlipidemic therapy is often instituted by a centralized pharmacist managed, physician monitored service,32,33 and at primary care medical offices, clinical pharmacy specialists conduct lipid management. These services likely in part explain the association between prescribing by a non-primary care department and the antihyperlipidemic subgroup.

We are unaware of any other study that has reported discriminative ability for logistic models for primary non-adherence. However, Chan et al. reported discriminative ability in modeling factors associated with adherence among patients dispensed statins.30 Their statin adherence model had a c-statistic of 0.63, similar to what we observed for antihyperlipidemics. Chan et al. concluded they had poor ability to explain adherence and that administrative data did not capture the many mechanisms underlying adherence.30 Although we used a comprehensive set of characteristics drawn from robust databases, our abilities to explain primary non-adherence or differentiate between patients likely to have ongoing dispensings or primary non-adherence was also poor. Further, the utilization, benefits, insurance, and prescriber characteristics in our models added little, as there was little difference between the c-statistics of full models and models containing only patient variables. Adherence is a complex behavior involving individual beliefs and psychosocial influences,30,34 and whether factors that motivate patients to initiate medication are the same as factors that result in ongoing adherence is unknown. Steiner and Chan and colleagues noted in their discussions of adherence after therapy initiation that determinants of behavior are more complex than the information available from administrative datasets.30,35 We believe this principle underlies our inability to either explain primary non-adherence or to differentiate between patients likely to have ongoing dispensings or primary non-adherence.

There are limitations to our work. As with any observational study, this study is subject to misclassification, specifically not capturing all orders or not allocating patients to correct adherence groups. However, because KPCO is an integrated system that utilizes an EHR and cares for a defined population, we completely identified orders, as all initial orders are documented in the EHR. Further, we linked orders with dispensings through internal systems that differentiate orders sent to KPCO pharmacies from orders for external dispensing. These capabilities contributed to accurately assigning patients to adherence groups.

This study had a fixed sample size that, although large overall, yielded some small subgroup numbers. We did not analyze the multiple medications subgroup due to concerns about sample size and power to detect differences. While we did find statistical differences between patients with primary non-adherence and ongoing dispensings in other subgroups, these must be interpreted with caution as these differences are not necessarily clinically important.

With the exception of the surrogate marker of healthcare contacts, we did not determine whether patients received adherence counseling, nor did we consider other patient–prescriber interactions. We did not assess potential markers of differences in behaviors, such as appointments made but not kept, or whether within-group adherence behaviors were consistent across other medications. Finally, assessing clinical outcomes was beyond the scope of our work.

We conclude that an important number of patients newly initiating an antihypertensive, antidiabetic, or antihyperlipidemic agent are primarily non-adherent and that primary non-adherence varies by therapeutic indication. We also conclude that patient, provider, and benefit characteristics available from clinical and administrative databases provide little assistance in explaining primary non-adherence. To directly address primary non-adherence, rather than using databases to attempt to predict patients likely to not initiate therapy, we recommend that healthcare systems pursue directly linking orders with dispensed prescriptions. This informatics solution can, with a high degree of accuracy, identify individuals with primary non-adherence. This linkage, supplemented with qualitative or mixed methods research to enhance understanding of patient attitudes and beliefs amenable to intervention and quantitative clinical trials to determine optimal interventions, can result in reduced numbers of patients with primary non-adherence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Capp Luckett for programming efforts. This study was supported by an internal grant from Kaiser Permanente Colorado. Dr. Schroeder is also supported by Training Grant 5 T32 DK007446 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Balkrishnan R. The importance of medication adherence in improving chronic-disease related outcomes: what we know and what we need to further know. Med Care. 2005;43:517–520. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000166617.68751.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker EA, Molitch M, Kramer MK, et al. Adherence to preventive medications: predictors and outcomes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1997–2002. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JR, Moser DK, DeJong MJ, et al. Defining an evidence-based cutpoint for medication adherence in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2009;157:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43:521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho PM, Magid DJ, Shetterly SM, et al. Importance of therapy intensification and medication nonadherence for blood pressure control in patients with coronary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:271–276. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGinnis BD, Olson KL, Delate TMA, Stolcpart RS. Statin adherence and mortality in patients enrolled in a secondary prevention program. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:689–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho PM, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1836–1841. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, Chan KA. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:565–574. doi: 10.1002/pds.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah NR, Hirsch AG, Zacker C, Taylor S, Wood GC, Stewart WF. Factors associated with first-fill adherence rates for diabetic medications: a cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:233–237. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0870-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beardon PHG, McGilchrist MM, McKendrick AD, McDevitt DG, MacDonald TM. Primary non-compliance with prescribed medication. Br Med J. 1993;307:846–868. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6908.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karter AJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, Ahmed AM, Schmittdiel JA, Selby JV. New prescription medication gaps: a comprehensive measure of adherence to new prescriptions. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(5p1):1640–1661. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah NR, Hirsch AG, Zacker C, et al. Predictors of first-fill adherence for patients with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:392–396. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer MA, Stedman MR, Lii J, et al. Primary medication non-adherence: analysis of 195,930 electronic prescriptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:284–290. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1253-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carroll NM, Ellis JL, Luckett C, Raebel MA. Feasibility of determining medication adherence from electronic health record medications orders. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011, doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA, Malone DC. Measurement of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: a proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1280–1288. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-Cm and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karter AJ, Parker MM, Adams AS, et al. Primary non-adherence to prescribed medications. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:763. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1381-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traylor AH, Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Subramanian U. Adherence to cardiovascular disease medications: does patient-provider race/ethnicity and language concordance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1172–1177. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1424-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Batal HA, Krantz MJ, Dale RA, Mehler PS, Steiner JF. Impact of prescription size on statin adherence and cholesterol levels. BMG Health Serv Res. 2007;7:175. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kripalani S, Gatti ME, Jacobson TA. Association of age, health literacy, and medication management strategies with cardiovascular medication adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;178(81):177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann DM, Woodward M, Munter P, Falzon L, Kronish I. Predictors of nonadherence to statins: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:1410–1421. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colombi AM, Yu-Isenberg K, Priest J. The effects of health plan copayments on adherence to oral diabetes medication and health resource utilization. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:535–541. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31816ed011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, Chan KA. Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacother. 2008;28:437–443. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann DM, Allengrante JP, Natarajan S, et al. Predictors of adherence to statins for primary prevention. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21:311–316. doi: 10.1007/s10557-007-6040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haskard Zolnierek HB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalsekar ID, Madhaven SS, Amonkar MM, et al. Depression in patients with type 2 diabetes: impact on adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:605–611. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mateo JF, Gil-Guillen VF, Mateo E, Orozco D, Carbayo JA, Merino J. Multifactorial approach and adherence to prescribed oral medications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:422–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tseng CW, Tierney EF, Gerzoff RB, et al. Race/ethnicity and economic differences in cost-related medication underuse among insured adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:261–266. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan DC, Shrank WH, Cutler D, et al. Patient, physician, and payment predictors of statin adherence. Med Care. 2010;48:196–202. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c132ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fung V, Sinclair F, Wang H, Dailey D, Hsu J, Shaber R. Patients' perspectives on nonadherence to statin therapy: a focus-group study. Permanente J. 2010;14:4–10. doi: 10.7812/tpp/09-090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olson KL, Rasmussen J, Sandhoff BG, Merenich JA, for the Clinical Pharmacy Cardiac Risk Service (CPCRS) Study Group Lipid management in patients with coronary artery disease by a clinical pharmacy service in a group model health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:49–54. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merenich JA, Olson KL, Delate T, et al. Mortality reduction benefits of a comprehensive cardiac care program for patients with occlusive coronary artery disease. Pharmacother. 2007;27:1370–1378. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.10.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steiner JF, Ho PM, Beaty BL, et al. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are not clinically useful predictors of refill adherence in patients with hypertension. Circulation: Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;2:452–457. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.841635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steiner JS. Can we identify clinical predictors of medication adherence … and should we? Med Care. 2010;48:193–195. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d51ddf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]