Abstract

In myasthenia gravis (MG) and experimental autoimmune MG (EAMG) many pathologically significant autoantibodies are directed at the main immunogenic region (MIR), a conformation-dependent region at the extracellular tip of α1 subunits of muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs). Human muscle AChR α1 MIR sequences were integrated into Aplysia ACh binding protein (AChBP). The chimera was potent at inducing both acute and chronic EAMG, though less potent than Torpedo electric organ AChR. Wild-type AChBP also induced EAMG but was less potent, and weakness developed slowly without an acute phase. AChBP is more closely related in sequence to neuronal α7 AChRs which are also homomeric, however autoimmune responses were induced to muscle AChR, but not to neuronal AChR subtypes. The greater accessibility of muscle AChRs to antibodies, compared to neuronal AChRs, may allow muscle AChRs to induce self-sustaining autoimmune responses. The human α1 subunit MIR is a potent immunogen for producing pathologically significant autoantibodies. Additional epitopes in this region or other parts of the AChR extracellular domain contribute significantly to myasthenogenicity. We show that an AChR-related protein can induce EAMG. Thus, in principle, an AChR-related protein could induce MG. AChBP is a water soluble protein resembling the extracellular domain of AChRs, yet rats which developed EAMG had autoantibodies to AChR cytoplasmic domains. We propose that an initial autoimmune response, directed at the MIR on the extracellular surface of muscle AChRs, leads to an autoimmune response sustained by muscle AChRs. Autoimmune stimulation sustained by endogenous muscle AChR may be a target for specific immunosuppression.

Keywords: myasthenia gravis, autoantibodies, AChBP, AChR, MIR

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an antibody-mediated autoimmune disease in which autoantibodies to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) in the postsynaptic membrane of the neuromuscular junction impair neuromuscular transmission [1–3]. Experimental autoimmune MG (EAMG) can be induced by active immunization with muscle-type AChRs from fish electric organs [2, 4, 5]. EAMG can be passively transfered by autoantibodies [6, 7]. The main immunogenic region (MIR) at the extracellular tip of AChR α1 subunits is targeted by more than half of the autoantibodies in both MG and EAMG [8–10]. The MIR is a region of closely spaced overlapping epitopes, several of which can be obscured by a single bound mAb [9]. Many of these epitopes include the MIR loop (α1 66–76). Amino acids 68 and 71 are particularly important, since mutations of either prevent binding of many mAbs to the MIR [11]. Many mAbs and serum autoantibodies bind only to conformationally mature α1 subunits [12]. The mature conformation of AChR subunits, and the MIR in particular, results from interaction between the N-terminal α helix (α1 1–14) and the MIR loop [13].

mAbs to the MIR passively transfer EAMG by targeting complement-dependent focal lysis and macrophage-mediated destruction of the postsynaptic membrane and by reducing the amount of AChRs through crosslinking, which facilitates internalization and lysosomal destruction (antigenic modulation) [1–3]. Thus antibodies to the MIR exhibit all the major pathological activities of MG sera. The transient acute phase of weakness observed 8–10 days after active immunization using strong adjuvants or 2–3 days after passive transfer of antibodies involves low but rapidly increasing concentrations of antibody which provoke transient release of C3 fragments of complement that attract macrophages [2, 4]. Macrophages are not involved in chronic EAMG, which typically develops 30 days after active immunization with AChR when antibody concentrations provoked by the depot of immunogen and adjuvant are at their peak, nor are macrophages involved in MG [2].

ACh binding proteins (AChBP) are water soluble proteins secreted by mollusk glia that are homologous in structure to the extracellular domain of homomeric AChRs [14, 15]. They are important as easily crystallized AChR models whose structure can be determined at high resolution [14–16]. We previously reported that a MIR/AChBP chimera, human AChR α1(1–30, 60–81)/AChBP, exhibited high affinity for mAbs to the MIR and reacted with antibodies from cats, dogs, and humans with MG [13].

Here we investigated induction of EAMG using this chimera. We made three important discoveries: 1) these conformation-dependent human MIR epitopes can potently induce EAMG; 2) wild-type ACh binding protein can itself induce EAMG, though less potently and much more slowly; and 3) induction of EAMG directed at the MIR on the extracellular tip of the AChR results in development of autoantibodies to the cytoplasmic domain of muscle AChRs. These discoveries have these important implications: 1) the MIR potently induces pathologically important autoantibodies which mediate EAMG, as expected; 2) distantly related structures resembling the extracellular domains of AChR subunits can induce EAMG, even though they lack the highly immunogenic vertebrate MIR; and 3) muscle AChR disrupted in the course of an autoimmune response to the extracellular domain serves as an immunogen which may sustain the autoimmune response. Disruption of this sustained autoimmunization may be a mechanism of specific immunosuppressive therapy [17].

Methods

Induction of EAMG

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania. Eight-week-old female Lewis rats (Charles River) were used. Rats were immunized once in the base of the tail by the subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of purified Torpedo AChR, wild-type AChBP, or human α1(1–32, 60–81)/AChBP chimera emulsified in TiterMax adjuvant (CytRx) [18]. Weakness was graded as follows: 0) no weakness; 1) weak grip or cry with fatigability; 2) hunched posture, lowered head, flexed forelimb digits, and uncoordinated movement; 3) severe generalized weakness, tremulous, moribund; and 4) dead [19].

Antigen preparation

Torpedo AChR was purified from Torpedo californica as described previously [18]. Aplysia AChBP and its chimera, flanked by an N-terminal FLAG epitope, were expressed as a soluble protein secreted from stably transfected HEK293S cells lacking the N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I (GnTI-) gene and purified by affinity chromatography as described previously [13].

Antibody assay

Antibodies to Torpedo electric organ, rat and human muscle AChRs were measured by immunoprecipitation of 125Iα bungarotoxin(125I-αBgt) labeled AChRs, and expressed as nmol of toxin binding sites precipitated/L serum (nM). Titers of antibodies to human α7 AChR were assayed by immune precipitation of 125I-αBgt labeled humanα7 AChRs from a HEK tsA201 cell line cotransfected with human α7 and RIC-3 (A. Kuryatov and J. Lindstrom, unpublished observations). Titers of antibodies to human α3β2 andα4β2 AChR were measured by immune precipitation of 3H epibatidine labeled AChRs from permanently transfected HEK cell lines [20, 21]. Antibodies to AChBP and MIR/AChBP chimera used 125I labeled proteins in immunoprecipitation assays as described previously [13]. Concentration was expressed as nmol of 125I AChBP or MIR/AChBP precipitated/L serum (nM).

ELISA

A mixture of human muscle AChR subunit large cytoplasmic domains in the ratio of 2:1:1:1:1 (α1:β1:γ:δ:ε) were expressed in bacteria as previously described [17]. This mixture of cytoplasmic domains was the same as used for specific immunosuppressive therapy of EAMG. Antibodies to the cytoplasmic domains were assayed by ELISA. Microtiter plates (Corning) were coated overnight at room temperature with 100μl of constructs (20μg/ml in 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9.6). After blocking with 3% BSA and washing, serially diluted EAMG rat sera were added for 2 h at 37°C. Bound antibodies were detected using biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) labeled streptavidin (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratory). HRP activity was measured with QuantaBlu Fluorogenic Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Pierce). Titer is defined as the dilution that gives half-maximal binding.

Statistics

Student’s two tailed t-test was used to determine the significance of differences between group means.

Results

Inducing EAMG by active immunization

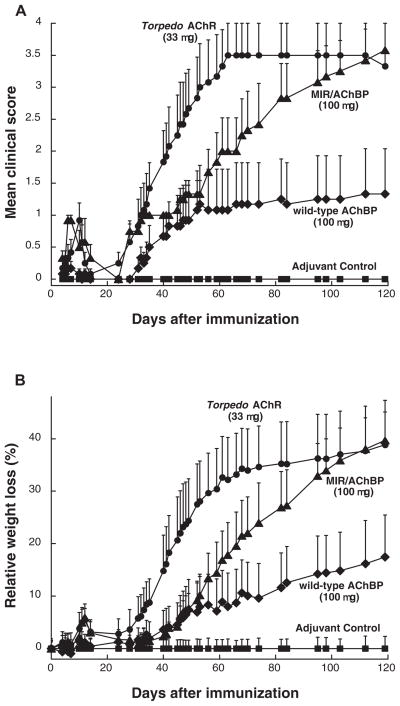

Rats were immunized once on day 0 with Torpedo AChR, Aplysia AChBP, or the chimera in TiterMax adjuvant. As expected, the MIR/AChBP chimera was potent at inducing EAMG (Figure 1 and Table 1). A single immunization with 11 μg of chimera caused acute EAMG around day 10, and chronic weakness starting around day 30. However, weakness was less severe than after immunization with 11 μg of Torpedo AChR. Rats immunized in adjuvant with a single dose of 100 μg of MIR/AChBP chimera eventually became as weak as those injected with 33 μg of Torpedo AChR, although EAMG developed more slowly. Four months after immunization, all six rats immunized with single dose of 100 μg developed weakness, and five died of EAMG (mean clinical score 3.58 as compared with mean clinical score 3.50 in rats immunized with 33 μg of Torpedo AChR).

Figure 1.

Comparison of induction of EAMG by immunization with Torpedo AChR, MIR/AChBP chimera, or wild-type AChBP. All rats, except adjuvant control (closed squares) which received only adjuvant, were immunized with single doses of 11, 33, or 100μg of antigens in TiterMax adjuvant at day 0. Data represent the mean ± SE (n = 6 for each point). (A) The mean clinical scores of the rats immunized with the chimera (closed triangles) developed more slowly, but ultimately were at the same level as those of the rats immunized with Torpedo AChR (closed circles) after day 82 (p < 0.05 ). The rats immunized with Torpedo AChR developed EAMG after day 34 (p < 0.05). The rats immunized with wild-type AChBP (closed diamonds) developed mild EAMG after day 40 (p < 0.16), but the mean clinical scores were significantly lower than those of the other two groups (p < 0.05). (B) A plot of relative weight loss as another measure of disease severity looks very similar. Relative weight loss was calculated as follows: % relative weight loss = 100 – (body weight on day X/average body weight of adjuvant control on day X) × 100.

Table 1.

Detailed Clinical Score Data for the EAMG Induction Experiments Shown in Fig 1.

| Immunogens | Phase of EAMG | Incidence of EAMG | Severity of EAMG (affected rats/total in group) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥0, <1 | ≥1, <2 | ≥2, <3 | ≥3, ≤4 | Mean | Deaths | ||||

| Torpedo AChR | 11 μg | Acute (day 10) | 4/6 | 2/6 | 3/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 0.92 | 0/6 |

| 33 μg | 5/6 | 1/6 | 4/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 1.00 | 0/6 | ||

| MIR/AChBP | 11 μg | 3/6 | 3/6 | 3/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0.58 | 0/6 | |

| 33 μg | 5/6 | 1/6 | 4/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 1.08 | 0/6 | ||

| 100 μg | 6/6 | 0/6 | 5/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 1.25 | 0/6 | ||

| Wild-typeAChBP | 11 μg | 0/6 | 6/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0.25 | 0/6 | |

| 33 μg | 0/6 | 6/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0.17 | 0/6 | ||

| 100 μg | 0/6 | 6/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0.17 | 0/6 | ||

| Torpedo AChR | 11 μg | Chronic (day 119) | 6/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 6/6 | 4.00 | 6/6 |

| 33 μg | 6/6 | 0/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 5/6 | 3.50 | 5/6 | ||

| MIR/AChBP | 11 μg | 3/6 | 1/6 | 3/6 | 0/6 | 2/6 | 1.83 | 2/6 | |

| 33 μg | 6/6 | 0/6 | 2/6 | 1/6 | 3/6 | 2.58 | 2/6 | ||

| 100 μg | 6/6 | 0/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 5/6 | 3.58 | 5/6 | ||

| Wild-type AChBP | 11 μg | 0/6 | 6/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0.00 | 0/6 | |

| 33 μg | 1/6 | 5/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0.17 | 0/6 | ||

| 100 μg | 3/6 | 3/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 2/6 | 1.33 | 1/6 | ||

Surprisingly, immunization with wild type AChBP also induced EAMG (Figure 1 and Table 1). Rats immunized with single doses of wild-type AChBP in adjuvant exhibited neither a substantial acute phase of weakness nor chronic weakness until day 52. EAMG developed slower and with less severity following immunization with wild-type AChBP than in rats immunized with chimera. However, 1 of 6 rats at the 33 μg dose and 3 of 6 rats at the 100 μg dose ultimately were weak.

Analysis of antibody specificities and concentrations induced by active immunization

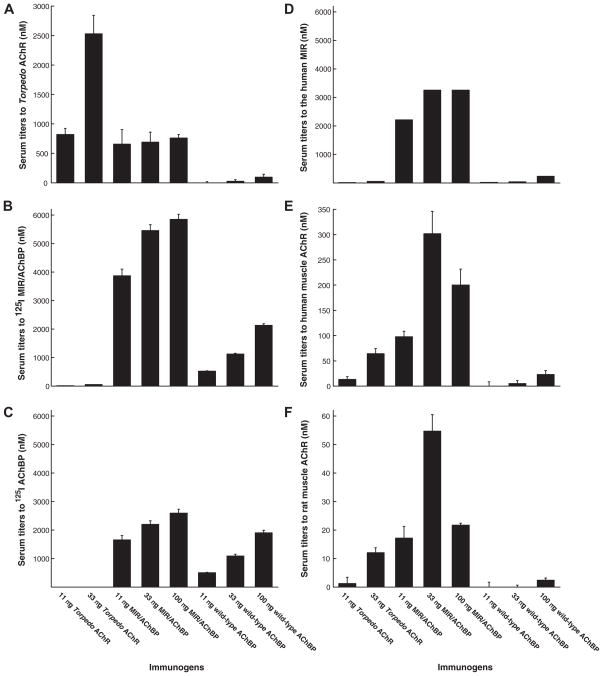

Immunization with Torpedo AChR produced large amounts of antibodies to itself, but few to the chimera or AChBP (Figure 2A, 2B, and 2C). Immunization with the MIR/AChBP chimera produced substantial titers to Torpedo AChR, but immunization with AChBP did not. Antibodies to the chimera which crossreacted with Torpedo AChR must be directed at the MIR. The chimera contains five fold more moles of muscle MIR than an equivalent weight of Torpedo AChR, accounting for the one way crossreaction. The mutual lack of crossreaction between AChBP and Torpedo AChR reflects how immunologically distinct these two proteins are. The MIR/AChBP chimera produced antibody titers to itself more than three-times as high as did wild-type AChBP at the same doses (Figure 2B and 2C). More than half of the antibodies induced by the chimera were directed at the MIR in the chimera (Figure 2D). This demonstrates that muscle α1 MIR is intrinsically highly immunogenic.

Figure 2.

Comparison of antibody specificities and concentrations induced by immunization with Torpedo AChR, MIR/AChBP chimera, or wild-type AChBP. Sera from rats used in Fig 1 and Table 1 were collected 120 days after the induction of EAMG. (A) Antibody titer to Torpedo AChR was evaluated by immunoprecipitation of AChRs labeled with 125I-αBgt. Immunization with Torpedo AChR induced high concentrations of antibody to Torpedo AChR. Immunization with the chimera produced relatively low titers to Torpedo AChR. Wild-type AChBP induced little antibody to Torpedo AChR. (B) Antibody titer to the chimera was assayed by immunoprecipitation of 125I MIR/AChBP. Immunization with Torpedo AChR induced little antibody to the chimera. The chimera induced high concentrations of antibody to itself. Wild-type AChBP induced relatively low concentrations of antibody to the chimera. (C) Antibody titer to wild-type AChBP was assayed by immunoprecipitation of 125I AChBP. Immunization with Torpedo AChR produced virtually no antibody to wild-type AChBP. The chimera produced higher concentrations of antibody to wild-type AChBP than did wild-type AChBP. (D) Antibody to the MIR was defined as concentration of antibody to the chimera minus that to the wild-type AChBP. This was highest for rats immunized with the chimera. (E) Antibody titer to human muscle AChR was evaluated by immunoprecipitation of 125I αBgt labeled AChRs from the TE671 cell line. Immunization with the chimera produced the highest antibody concentrations, though Torpedo AChR produced a significant amount. (F) Antibody titer to rat muscle AChR was assayed by immunoprecipitation of 125I αBgt labeled AChRs from rat muscle. Immunization with the chimera also produced the highest antibody concentrations to rat muscle AChRs. The concentrations of antibodies to rat AChRs were less that 1/6 of those to human AChR.

Immunization with the chimera produced higher antibody titers to human and rat muscle AChRs than did immunization with Torpedo AChR (Figure 2E and 2F). As in rats immunized with Torpedo AChR, the concentrations of antibodies to rat muscle AChRs were less than 1/6 of those to human muscle AChRs in rats immunized with the chimera. This implies substantial autoantibody discrimination by the rat immune system even when stimulated by highly conserved human muscle MIR epitopes. This suggests that in EAMG tolerance to the AChR may not be so much “broken” as “bent”, since titers to endogenous AChR are much lower that to exogenous AChR.

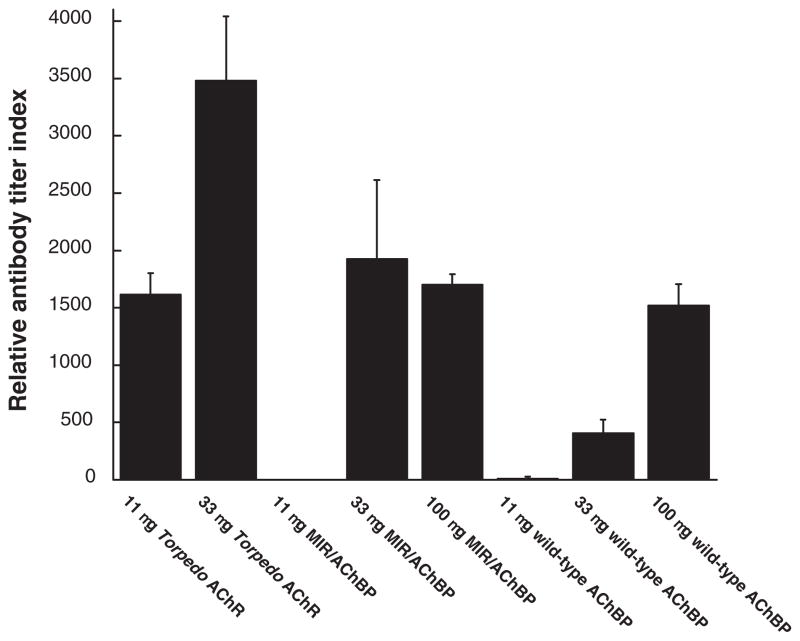

Antibodies to cytoplasmic domains in rats which developed EAMG

Rats that developed severe EAMG also developed substantial titers of antibody to cytoplasmic domains, even when the initial immunogens did not contain cytoplasmic domains (wild-type AChBP and chimera) (Figure 3). By four months after immunization, antibody concentrations to AChR cytoplasmic domains were nearly as high in rats immunized with chimera and wild-type AChBP as in rats immunized with Torpedo AChR. Since the chimera and AChBP do not have cytoplasmic domains, autoantibodies to cytoplasmic domains must result from immune stimulation by muscle AChRs disrupted in the course of EAMG initially directed at their extracellular surface.

Figure 3.

Titers of antibodies to cytoplasmic domains in sera from rats immunized with Torpedo AChR, MIR/AChBP chimera and wild-type AChBP. These are rats used in Table 1. Rat sera were collected 120 days after the induction of EAMG.

Antibody titers to the cytoplasmic domains were evaluated by ELISA assays described in Materials and Methods using the mixture of human AChR subunit cytoplasmic domains used for specific immunosuppressive therapy of EAMG[17].

The three groups of rats that did not develop substantial EAMG did not develop antibody to AChR cytoplasmic domains (rats immunized with 11 μg chimera or 11 or 33μg wild-type AChBP) (Figure 3).

Analysis of cross-reactivity of rat sera with neuronal nicotinic AChRs

Antibodies from rats immunized with AChBP, MIR/AChBP chimera, or Torpedo AChR did not crossreact with human α3*, α4*, or α7 AChRs. Sera were from the termination of the EAMG induction experiment shown in Table 1.

Discussion

Our results imply that: 1) these conformation-dependent human AChR α1 subunit MIR epitopes induce pathologically important autoantibodies which mediate EAMG; 2) distantly related structures resembling the extracellular domains of AChR subunits such as AChBP can induce EAMG; and 3) immune stimulation by endogenous AChR released in the immune assault initially on the MIR may be a major factor in sustaining the autoimmune response in EAMG, and may be a major target at which specific immunosuppressive therapy acts [17].

Myasthenia gravis is caused by antibodies to muscle AChRs [1–3], but is associated with the presence of autoantibodies to many other proteins [22]. These other autoantibodies may reflect a genetic proclivity for antoimmune responses in MG patients, and may in some cases modify the impaired neuromuscular transmission in MG which results from loss of AChRs and disruption of the postsynaptic membrane. Autoantibodies to AChRs in MG are directed at many parts of the AChR protein, especially the MIR at the extracellular tip of α subunits.

All AChR subunits have structures homologous to the MIR, but the MIR on muscle-type AChR α1 subunits is uniquely immunogenic and myasthenogenic [2, 14, 16]. The MIR is responsible for provoking half or more of the autoantibodies to muscle AChRs in EAMG and MG in several species [10, 23, 24]. Antibodies to the MIR play a crucial pathological role since: 1) mAbs to the MIR can passively transfer EAMG [7]; 2) Fab fragments of these mAbs can efficiently protect the AChR in cell culture against antigenic modulation induced by MG sera [25]; and 3) these mAbs can induce complement-dependent focal lysis of the postsynaptic membrane and antigenic modulation [2].

We previously proved that the native conformation of the MIR results from interaction between the MIR loop (α1 66–76) and the N-terminal α helix (α1 1–14) [13]. This interaction nucleates conformational maturation of AChR subunits, thereby promoting assembly of mature AChRs. The chimeraα1(1–30, 60–81)/AChBP contains sequences of human α1 required to form epitopes with very high affinity for mAbs to the MIR. The chimera reacts with antibodies from cats, dogs and humans with MG. However, the fraction of MG antibodies adsorbed by the chimera is lower than the fraction of serum antibodies prevented from binding to AChR by a mAb to the MIR. Thus, the MIR of muscle AChR contains more closely spaced epitopes than are present in this chimera. These epitopes may include additional α1 sequences and /or sequences of adjacent subunits.

This chimera was potent at inducing EAMG (Figure 1). Thus, the MIR epitopes it contains are sufficient to initiate a pathological autoimmune response. Wild-type AChBP also induced EAMG, but was less potent, did not initiate a transient early acute phase, and slowly produced a chronic phase of progressive weakness long after the maximum response to the inducing immunogen would be expected [18]. This suggests that the extracellular epitopes on AChBP which crossreact with muscle AChR initiate an autoimmune response which is ultimately sustained by the muscle AChR itself. Evidence for this concept is that rats which developed EAMG after immunization with AChBP or the MIR/AChBP chimera developed antibodies to muscle AChR cytoplasmic domains of similar concentration to those developed after induction of EAMG with immunization by Torpedo AChR. Since AChBP contains no cytoplasmic domains, these antibodies must have been provoked by muscle AChR disrupted by the immune attack on the extracellular surface.

Antibody titers produced by the chimera were at least three-times higher than those produced by wild-type AChBP (Figure 2). Moreover, more than half of these antibodies targeted the sequences of human α1 in the chimera. This demonstrates the intrinsic myasthenogenicity and immunogenicity of these sequences of humanα1subunits. All AChR subunits and AChBP have N-terminal α helix and MIR loop structures with the same basic shape as the MIR in α1 subunits [14, 16]. Thus, the particular immunogenicity of the a1 MIR depends on subtleties of sequence and conformation.

EAMG induced by the chimera developed more slowly and was less severe than that induced by equivalent amounts of Torpedo AChR, although the chimera produced much higher antibody titers to rat muscle AChR than did Torpedo AChR. Antigenic modulation requires crosslinking of AChRs, which results in an increase of the internalization and degradation rate of the AChR [25]. Antibodies bound to AChRs in the postsynaptic membrane also need to achieve a threshold density to activate complement [26, 27]. Therefore, both of the primary pathological activities of serum antibodies depend on the ability of the antibodies to crosslink AChRs. The MIR is present twice on each AChR molecule, and oriented away from the central axis of the AChR, which allow antibodies to the MIR to be more effective at crosslinking adjacent AChRs than antibodies to epitopes other than the MIR [2, 16]. The MIR is a region containing a set of largely overlapping epitopes [2, 9]. A single antibody bound to an epitope in this region prevents many of the other antibodies to the MIR from binding to this region. Antibodies to the MIR will compete with each other for binding to this region and thus allow only two antibody molecules to be bound on the same AChR. Very high ratios of antibody/AChR will inhibit crosslinking by saturating all antibody binding sites. Antibodies to the MIR alone will be less effective at crosslinking AChRs than a mixture of antibodies to the MIR and to other epitopes. A few nanomoles of mAbs to the MIR were required to passively transfer EAMG into healthy rats [7]. Only 70 picomoles of serum antibodies from rats with EAMG can passively transfer EAMG [6]. Immunization with wild-type AChBP produced very little antibody to rat muscle AChR (Figure 2F). This suggests that antibodies to rat muscle AChR produced by the chimera were primarily directed at the MIR of human α1 present in the chimera, but not the remaining AChBP sequences. This can explain why the antibodies produced by immunization with the chimera appeared to be less pathogenic than the antibodies produced by immunization with Torpedo AChR. This also suggests that the myasthenogenicity of whole serum is not a simple sum of its parts. The myasthenogenicity of a single antibody depends on the presence of other antibodies.

The MIR loop contributes to binding of 57% of MG patient autoantibodies, as revealed by loss of binding when α1 66–76 of human muscle AChR is replaced with α7 66–76. This corresponds very well to the 55% inhibition of MG patient autoantibody binding by mAb 35 to the MIR [13]. However, even though the MIR/AChBP chimera binds mAbs to the MIR with high affinity, it adsorbs only 15% of MG patient sera [13]. mAb 35 binds 20 fold better with mature AChRs than with unassembled α1 subunits, and MG patient sera bind on the average 14 fold better with AChR than free α1 [12]. This suggests that many MG patient MIR epitopes depend for their conformations on sequences from adjacent subunits, or that amino acids from these subunits contribute directly as contact amino acids for these epitopes. Thus, the absence of these sequences from adjacent subunits in the chimera may also be responsible for the less potent myasthenogenicity of the chimera when compared with Torpedo AChR.

AChBP is a homolog of the extracellular domain of AChRs, but shows limited sequence identity with them [14, 15]. Aplysia AChBP has the highest sequence identity to the extracellular domain of the α7 and α3 AChR subunits (24% and 23% respectively) [15]. It displays 20% sequence identity with α1 subunits of muscle AChR, and lower sequence identity to the other subunits of muscle AChR. Thus, one might expect that antibodies induced by active immunization with wild-type AChBP would crossreact with α7 AChR at least as well as with muscle AChR. However, immunization with 100 μg of wild-type AChBP produced no antibody to α7 AChR, although it produced substantial antibodies to both human and rat muscle AChRs. This suggests that most of the antibodies to muscle AChR 120 days after induction of EAMG with wild-type AChBP did not result from initial immune stimulation with wild-type AChBP. Our data also showed that only rats which developed EAMG developed substantial amounts of antibody to muscle AChR and to cytoplasmic domains (Figure 2E, 2F and Figure 3). This implies that antibodies to muscle AChR formed in rats initially immunized with wild-type AChBP must result from immune stimulation by muscle AChRs disrupted by the initial response to the immunogen. This phenomenon is known as epitope spreading [28].

These results are consistent with a previous report that rats immunized with 500 μg of denatured bacterially-expressed extracellular domain of human α1 AChR subunits first developed antibodies to the extracellular domain but later developed antibody to human α1 AChR cytoplasmic domain when they began to develop EAMG [29]. Immune stimulation by endogenous AChR released in the immune assault may be a major factor in sustaining the autoimmune response in EAMG and MG, and may be a major target at which specific immunosuppressive therapy acts.

What initiates the autoimmune response to AChR in MG still remains a mystery [2]. The thymus is suspected to be the site where the autoimmune response to AChRs is triggered in MG [30, 31]. It has been suggested that molecular mimicry of the AChR by a short sequence of a bacterial or viral protein could initiate the immune response, then reaction with authentic AChR could lead to epitope spreading. The possibility exists in humans that MG may be triggered by exogenous antigens that carry structural features which are similar to regions on AChR [32]. Aplysia AChBP is capable of inducing EAMG. The AChBP has the basic shape of an α7 AChR extracellular domain, but only 24% sequence identity with homomeric α7 AChRs, and ≤ 20% with muscle AChR subunits. This proves that proteins distantly related to muscle type AChRs can induce EAMG.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Campling and Diane Shelton for their comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- EAMG

experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis

- MG

myasthenia gravis

- MIR

main immunogenic region

- AChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- AChBP

acetylcholine binding protein

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: This work was supported by grants to Jon Lindstrom from the National Institutes of Health (NS11323 and NS052463). The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Conti-Fine BM, Milani M, Kaminski HJ. Myasthenia gravis: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(11):2843–2854. doi: 10.1172/JCI29894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindstrom JM. Acetylcholine receptors and myasthenia. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23(4):453–477. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200004)23:4<453::aid-mus3>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent A, Palace J, Hilton-Jones D. Myasthenia gravis. Lancet. 2001;357(9274):2122–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindstrom JM, Einarson BL, Lennon VA, Seybold ME. Pathological mechanisms in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. I. Immunogenicity of syngeneic muscle acetylcholine receptor and quantitative extraction of receptor and antibody-receptor complexes from muscles of rats with experimental automimmune myasthenia gravis. J Exp Med. 1976;144(3):726–738. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.3.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patrick J, Lindstrom J. Autoimmune response to acetylcholine receptor. Science. 1973;180(88):871–872. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4088.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindstrom JM, Engel AG, Seybold ME, Lennon VA, Lambert EH. Pathological mechanisms in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. II. Passive transfer of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis in rats with anti-acetylcholine recepotr antibodies. J Exp Med. 1976;144(3):739–753. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.3.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzartos S, Hochschwender S, Vasquez P, Lindstrom J. Passive transfer of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis by monoclonal antibodies to the main immunogenic region of the acetylcholine receptor. J Neuroimmunol. 1987;15(2):185–194. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(87)90092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beroukhim R, Unwin N. Three-dimensional location of the main immunogenic region of the acetylcholine receptor. Neuron. 1995;15(2):323–331. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tzartos SJ, Barkas T, Cung MT, Mamalaki A, Marraud M, Orlewski P, Papanastasiou D, Sakarellos C, Sakarellos-Daitsiotis M, Tsantili P, Tsikaris V. Anatomy of the antigenic structure of a large membrane autoantigen, the muscle-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Immunol Rev. 1998;163:89–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tzartos SJ, Seybold ME, Lindstrom JM. Specificities of antibodies to acetylcholine receptors in sera from myasthenia gravis patients measured by monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(1):188–192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.1.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saedi MS, Anand R, Conroy WG, Lindstrom J. Determination of amino acids critical to the main immunogenic region of intact acetylcholine receptors by in vitro mutagenesis. FEBS Lett. 1990;267(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80286-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conroy WG, Saedi MS, Lindstrom J. TE671 cells express an abundance of a partially mature acetylcholine receptor α subunit which has characteristics of an assembly intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(35):21642–21651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo J, Taylor P, Losen M, de Baets MH, Shelton GD, Lindstrom J. Main immunogenic region structure promotes binding of conformation-dependent myasthenia gravis autoantibodies, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor conformation maturation, and agonist sensitivity. J Neurosci. 2009;29(44):13898–13908. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2833-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brejc K, van Dijk WJ, Klaassen RV, Schuurmans M, van Der Oost J, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2001;411(6835):269–276. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen SB, Sulzenbacher G, Huxford T, Marchot P, Taylor P, Bourne Y. Structures of Aplysia AChBP complexes with nicotinic agonists and antagonists reveal distinctive binding interfaces and conformations. Embo J. 2005;24(20):3635–3646. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unwin N. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2005;346(4):967–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo J, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom JM. Specific immunotherapy of experimental myasthenia gravis by a novel mechanism. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(4):441–451. doi: 10.1002/ana.21901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindstrom JM, Lennon VA, Seybold ME, Whittingham S. Experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis and myasthenia gravis: biochemical and immunochemical aspects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;274:254–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb47691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lennon VA, Lindstrom JM, Seybold ME. Experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis: cellular and humoral immune responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;274:283–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb47693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuryatov A, Luo J, Cooper J, Lindstrom J. Nicotine acts as a pharmacological chaperone to up-regulate human α4β2 acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68(6):1839–1851. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.012419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Olale F, Cooper J, Keyser K, Lindstrom J. Chronic nicotine treatment up-regulates human α3β2 but not α3β4 acetylcholine receptors stably transfected in human embryonic kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(44):28721–28732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vrolix K, Fraussen J, Molenaar PC, Losen M, Somers V, Stinissen P, De Baets MH, Martinez-Martinez P. The auto-antigen repertoire in myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity. 2010;43(5–6):380–400. doi: 10.3109/08916930903518073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shelton GD, Cardinet GH, Lindstrom JM. Canine and human myasthenia gravis autoantibodies recognize similar regions on the acetylcholine receptor. Neurology. 1988;38(9):1417–1423. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.9.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tzartos S, Langeberg L, Hochschwender S, Lindstrom J. Demonstration of a main immunogenic region on acetylcholine receptors from human muscle using monoclonal antibodies to human receptor. FEBS Lett. 1983;158(1):116–118. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzartos SJ, Sophianos D, Efthimiadis A. Role of the main immunogenic region of acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis. An Fab monoclonal antibody protects against antigenic modulation by human sera. J Immunol. 1985;134(4):2343–2349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoyer LW, Trabold NC. The significance of erythrocyte antigen site density. II. Hemolysis. J Clin Invest. 1971;50(9):1840–1846. doi: 10.1172/JCI106675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong JT, Colvin RB. Bi-specific monoclonal antibodies: selective binding and complement fixation to cells that express two different surface antigens. J Immunol. 1987;139(4):1369–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, Nishikawa T, Zone JJ, Black MM, Wojnarowska F, Stevens SR, Chen M, Fairley JA, Woodley DT, Miller SD, Gordon KB. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110(2):103–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feferman T, Im SH, Fuchs S, Souroujon MC. Breakage of tolerance to hidden cytoplasmic epitopes of the acetylcholine receptor in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;140(1–2):153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hohlfeld R, Wekerle H. The role of the thymus in myasthenia gravis. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1994;4(4):373–386. doi: 10.1016/0960-5428(94)00040-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moulian N, Wakkach A, Guyon T, Poea S, Aissaoui A, Levasseur P, Cohen-Kaminsky S, Berrih-Aknin S. Respective role of thymus and muscle in autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;841:397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deitiker P, Ashizawa T, Atassi MZ. Antigen mimicry in autoimmune disease. Can immune responses to microbial antigens that mimic acetylcholine receptor act as initial triggers of Myasthenia gravis? Hum Immunol. 2000;61(3):255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(99)00117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]