Abstract

Taking into consideration the relative number of people living in Papua New Guinea the burden of malaria in this country is among the highest in Asia and the Pacific region. This article summarizes the research questions and challenges being undertaken by the Southwest Pacific International Center of Excellence for Malaria Research in the context of the epidemiology, transmission and pathogenesis of Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax at the present time and the recent past. It is hoped that the research accomplished and local infrastructure strengthened by this effort will help inform regional and national policy with regard to the control and ultimately elimination of malaria in this region of the world.

Keywords: Malaria, Papua New Guinea, Melanesia, Epidemiology, Vector Control, Transmission, Acquired Immunity

1.1 Introduction

This paper is an overview of the goals and background to research to be undertaken by the Southwest Pacific International Center of Excellence for Malaria Research (SW Pacific ICEMR) sponsored by the United States National Institutes of Health. Activities concerned with work to be conducted in Papua New Guinea (PNG) are discussed. SW Pacific ICEMR activities will also occur in the Solomon Islands, where the level of malaria endemicity is considerably lower than in many areas of PNG. However, because recent data relevant to malaria infection and morbidity among the many widely dispersed islands that make up this nation are limited, a description of the research challenges and goals for ICEMR activities in the Solomon Islands awaits completion of ongoing efforts to select a suitable study site.

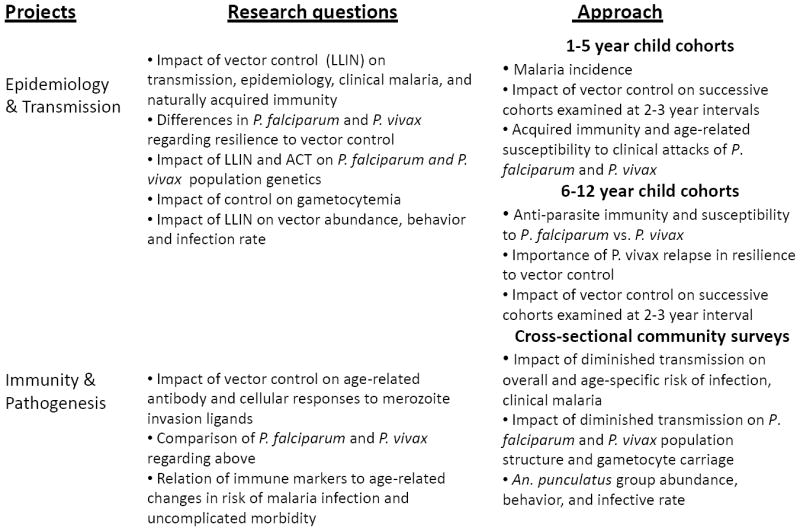

An overarching goal of the SW Pacific ICEMR is to advance knowledge of how selected aspects of the 2009-2013 National Malaria Control Program Strategic Plan of the PNG Department of Health (a copy of the plan is available at the following URL http://yumirausimmalaria.com/FINAL%20NMCP%20Strategic%20Plan%202009-2013%2024_10_08.pdf) affect the epidemiology, transmission and pathogenesis of this infectious disease. Features of the plan that are particularly relevant to the ICEMR include the following public health interventions: (i) widespread distribution of free long lasting insecticide treated bed nets (LLINs); (ii) re-introduction of indoor spraying with residual insecticides in some areas; (iii) use of artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) with artemether-lumefantrine (AL) as the first line anti-malarial for treatment of uncomplicated malaria; and (iv) improved malaria infection diagnosis that includes rapid diagnostic tests (RDT). ICEMR research projects will involve observational studies of human subjects and complementary transmission assessment of sympatric mosquito vectors in East Sepik Province and Madang Province, two hyper- to holoendemic areas where the PNG Institute of Medical Research (IMR) and its collaborating institutions have previously conducted malaria research. A summary of the specific research questions that will be addressed during the seven-year course of the ICEMR is presented in Figure 1. The sections below describe the background and rationale for these research objectives in the context of the historical and current malaria burden in PNG. Features of the malaria burden that are particularly relevant to the ICEMR include the co-endemicity of hyper- to holoendemic falciparum and vivax malaria, the complexity and relatively limited knowledge of malaria vectors, and anti-malarial drug resistance.

Figure 1.

Summary of research objectives and study design of the Southwest Pacific International of Excellence for Malaria Research activities in Papua New Guinea

1.2 Epidemiology of malaria infection and morbidity

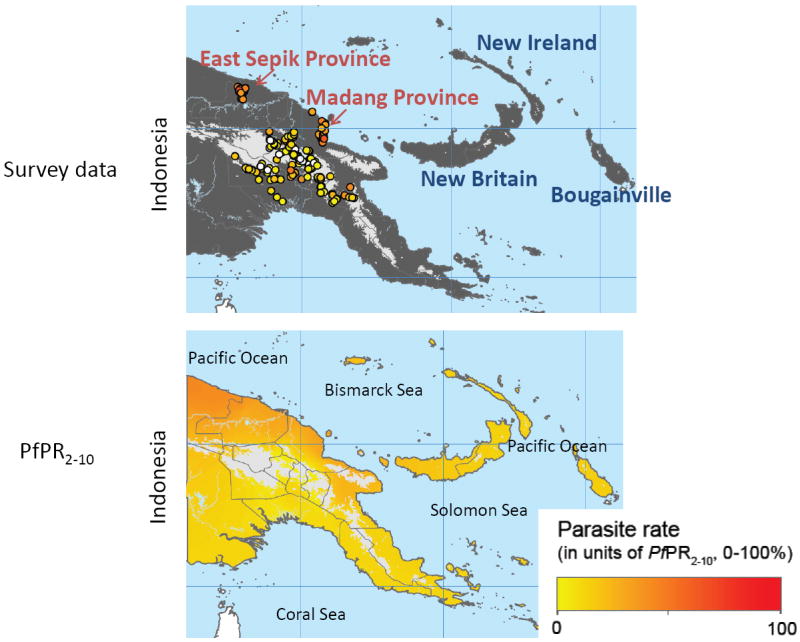

Four of the five malaria species known to infect humans, P. falciparum, vivax, malariae and ovale, are endemic in PNG, a country of approximately 6.5 million people that includes the eastern portion of the main island of New Guinea and smaller islands located in the Bismarck, Solomon and Coral Seas. The intensity of malaria transmission is geographically variable throughout PNG (Figure 2). Perennial high intensity transmission is present in many coastal and lowland inland areas along the north coast of the main island, particularly Madang Province and East Sepik Province. Recent census information indicates that approximately 13 percent of the nation’s population resides in these two provinces. Malaria transmission is less intense along the south coast of the main island, outlying island provinces such as New Britain, New Ireland and Bougainville and at higher altitudes in central highland regions (Cattani, 1992; Muller et al., 2003; Van Dijk and Parkinson, 1974). Within each of these relatively large geographic regions there is fine scale spatial heterogeneity of malaria endemicity at the village or even household cluster level (Cattani et al., 1986a; Mueller et al., 2009b; Smith et al., 2001b). Local heterogeneity in community infection rates is believed to be due to varying availability and use of anti-malarial drugs and bed nets and differences in local vector abundance and ecology (Burkot et al., 1988; Hii et al., 1997; Kasehagen et al., 2006; Mueller et al., 2009b; Smith et al., 2001b)

Figure 2.

Malaria endemicity in Papua New Guinea estimated by the Malaria Atlas Project (Hay and Snow, 2006)

The upper panel shows areas of the country where data for the Malaria Atlas Project were obtained. Provinces highlighted in red are where studies conducted by the SW Pacific ICEMR will take place. The lower panel is a heat map of the estimated level of malaria endemicity for all regions of PNG.

The prevalence of malaria infection is greatest among children younger than five years old and pregnant women (Allen et al., 1998; Brabin et al., 1990; Genton et al., 1995b). P. falciparum and vivax account for the majority of infections. P. malariae and ovale are also present, usually in combination with the former two species (Mehlotra et al., 2002; Mehlotra et al., 2000). With regard to age-specific prevalence, P. vivax infection is predominant among children younger than three years whereas P. falciparum is more common among older children and across all age groups (Mueller et al., 2009b). P. malariae occurs mainly in adults and older children (Mueller et al., 2009b; Smith et al., 2001b). There appear to be no significant malaria species interactions that affect the prevalence or density of parasitemia. Cross-sectional surveys of different populations in PNG showed a random distribution or excess of mixed species infection documented by microscopic inspection of blood smears and polymerase chain reaction detection of malaria species-specific DNA (Mehlotra et al., 2002; Mehlotra et al., 2000; Mueller et al., 2009b). In two longitudinal studies with different designs, negative correlations were found among Plasmodium species detected microscopically by blood smear (Bruce et al., 2000b; Smith et al., 2001a).

With respect to morbidity, uncomplicated malaria is among the most common identifiable causes of non-lethal febrile illness affecting children and adolescents (Genton et al., 2008). Among children younger than two years, an age group in which pneumococcal pneumonia and other bacterial infections frequently cause febrile illness (Duke et al., 2002; Lehmann, 2002; Lehmann et al., 1988), P. vivax is more likely than P. falciparum to underlie malaria-related fever (Lin et al., 2010a). In contrast, attacks of uncomplicated falciparum malaria persist up to approximately age 12 years (Michon et al., 2007). Limited information regarding the possible impact of cross-species interactions on uncomplicated malaria morbidity is available. Based on an analysis of health center surveillance and population based survey data from East Sepik Province collected from 1991 to 2002, a strong negative association among various malarial species and paucity of mixed species infections was observed in persons with symptomatic malaria relative to age-matched, asymptomatic malaria-infected controls (Stanisic et al., 2010). Similarly, the risk of health center attendance with P. falciparum-associated fever decreased following asymptomatic P. vivax infection, while pre-existing infection with P. malariae was associated with relative protection against non-falciparum related fever. Taken together, these data suggest some form of cross-species protection against clinical malaria, possibly by changing the fever threshold or parasite density. Alternatively, the host response to super-infection with a new malaria species could result in the pre-existing asymptomatic infection being suppressed below a level that is detectable by microscopic inspection of blood smears. Both interpretations are consistent with earlier work in PNG which demonstrated density dependent protective processes related to mixed species infections (Bruce et al., 2000a). More detailed longitudinal studies with molecular diagnosis of blood stage infection will be required to shed further light on possible cross-species interactions and their impact of clinical illness due to malaria.

There is considerably less information with respect to the prevalence and manifestations of severe malaria. Falciparum malaria has been reported to cause seizures, coma, acidosis and severe anemia in children in a high transmission area served by the Madang provincial hospital (Allen et al., 1996a; Allen et al., 1996b). Studies of pregnancy malaria conducted before insecticide treated bed nets were distributed showed that placental malaria infection was frequent, particularly among primigravida women (Allen et al., 1998; Desowitz and Alpers, 1992). Maternal anemia and low birth newborns were common in women in the 1990s (Allen et al., 1998). In areas of the country where there has been increasing coverage with LLIN and distribution of anti-malarial drugs to pregnant women this situation is likely improving (Mueller et al., 2008), but the magnitude of the benefit remains to be quantified by ongoing health surveillance programs. There is no published information regarding birth outcomes related to pregnancy malaria in the many remote rural areas of PNG where pre-natal care and child birth occur in the village setting.

Although historically considered clinically benign, P. vivax and mixed P. vivax/falciparum infection have been documented to cause severe malaria in PNG and the adjoining Indonesian province of (West) Papua which constitutes the western portion of the island of New Guinea. An observational study of presumptive malaria cases presenting to two rural health centers in East Sepik Province over an eight-year period reported that 6.2 percent of 9,537 cases with confirmed Plasmodium species parasitemia met the local case definition of severe malaria (hemoglobin less than 5 grams per dL, recent seizures or coma, respiratory distress) (Genton et al., 2008). The relative risk of severe manifestations was highest in infants and young children less than two years old; 18 percent of those in this age range with P. falciparum infection alone presented with signs of severe malaria. Fourteen and 29 percent of this age group with P. vivax and mixed P. falciparum/vivax infection also met the case definition of severe malaria. There was a significant decline in the frequency of severe malaria with increasing age. In the rural outpatient setting of this study systematic follow up for mortality was not realistic. However, two hospital-based studies in different regions of the neighboring Indonesian province Papua found comparable risks of severe P. falciparum and P. vivax malaria, and higher risk of severe malaria among hospital attendees with mixed P. falciparum/vivax infection (Barcus et al., 2007; Tjitra et al., 2008). Mortality for severe cases for all malaria species combined was, respectively, 24.0 and 6.7 percent for the Barcus and Tjitra studies. Unlike observations from East Sepik Province, adults as well as children were found to have severe (and occasionally fatal) malaria in the Indonesian studies, possibly reflecting lower transmission intensity and the presence of a significant migrant population in these areas. Severe P. vivax morbidity and mortality in the Indonesian study sights may also be related to the existence of multi-drug resistant P. vivax (Ratcliff et al., 2007a; Ratcliff et al., 2007b). Subsequent reports from southern Papua (Timika study site) have documented that the case fatality rate for severe malaria due to P. falciparum and P. vivax was similar among infants less than one year, that P. vivax posed a greater risk for severe anemia than P. falciparum (Poespoprodjo et al., 2009) and that P. vivax mono-infection may cause coma, though at a 23-fold lower risk relative to P. falciparum (Lampah et al., 2011).

1.3 Human genetic polymorphism under natural selection by malaria

Evidence of the importance of malaria in natural selection in local Melanesian populations in PNG and nearby countries such as the Solomon Islands includes the presence of genetic polymorphisms that are thought to protect against severe malaria or blood stage infection. These polymorphisms include Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, α-thalassemia, Southeast Asian ovalocytosis, a promoter mutation that silences expression of the Duffy Antigen Receptor for Chemokines on red blood cells, Melanesian Gerbich blood group negativity and expression of red blood cell Complement Receptor 1 (Allen et al., 1997; Cattani et al., 1987; Cockburn et al., 2004; Genton et al., 1995c;Hill et al., 1988; Mgone et al., 1996; O’Donnell et al., 1998; Patel et al., 2001; Serjeantson et al., 1992; Yenchitsomanus et al., 1986; Zimmerman et al., 2003; Zimmerman et al., 1999). The prevalence of several of these polymorphisms is high in PNG, e.g. 36.9 and 56.0 percent for −α/αα and −α/-α thalassemia, 8.8 percent for Southeast Asian ovalocytosis in populations along the north coast of Madang Province, 6.6 percent for severe G6PD deficiency and 46.0 percent for exon 3 deletion of red blood cell glycophorin C (Gerbich blood group) in inland regions of East Sepik Province (Fowkes et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2010b; Patel et al., 2001). G6PD deficiency has potentially important health implications since the only drug currently approved for elimination of liver stage P. vivax hynozoites, primaquine, may cause hemolysis among persons with severe deficiency of this erythrocyte anti-oxidant enzyme (Baird and Hoffman, 2004). The research activities of the SW Pacific ICEMR will include examination of these polymorphisms and determination of whether they are associated differentially with susceptibility to clinical illness from P. falciparum, P. vivax and mixed P. falciparum/vivax infection.

1.4 Malaria vectors

The anopheline fauna in PNG is remarkably diverse and includes 16 species (Cooper et al., 2009). The main vectors species in the country and neighboring Southwest Pacific island nations belong to the Anopheles punctulatus complex. The complex has traditionally been divided into the three morphs, An. punctulatus, An. farauti and An. koliensis, and is now know to consist of at least nine genetically distinct (partially isomorphic) species (Beebe et al., 2000; Beebe and Saul, 1995; Benet et al., 2004). Unlike the primary vectors of malaria in Africa, An. gambiae and An. funestus which are anthropophilic, endophilic and endophagic, the information available on members of the An. punctulatus complex suggests that these species are predominantly zoophilic, exophilic and exophagic (Burkot et al., 1988; Burkot et al., 1989). Members of the complex likely have different geographical and altitudinal distribution, biting behavior and larval habitats (Benet et al., 2004; Cooper et al., 2002), and may therefore occupy distinct ecological niches. While the vector status of the major morphs is well established, the vectorial capacity of most isomorph sub-species remains to be determined.

The high species and behavioral diversity of PNG anophelines are likely to impact the efficacy of various vector control measures as the local mosquito populations may be able adapt and/or evolve avoidance strategies. Notably, previous experience from malaria elimination efforts in PNG showed that intensive residual spraying with insecticides resulted in a significant change in vector behavior that was characterized by a shift in peak biting time from late to early evening (Taylor, 1975). Importantly, behavioral changes in the mosquito population persisted after earlier control and elimination efforts were abandoned, suggesting that there was a genetic basis to the observed phenomenon. An important research goal of the SW Pacific ICEMR is to advance understanding of how the current national program of achieving universal bed net coverage (defined as one LLIN for every two household residents) affects the behavior (e.g. peak biting time), abundance and insecticide resistance of malaria vectors in high transmission areas of the country.

1.5 Anti-malarial drug resistance and tolerance

Anti-malarial drug resistance is widespread in PNG. P. falciparum resistance to chloroquine (CQ) was first documented in 1976 (Grimmond et al., 1976; Yung and Bennett, 1976). Resistance to CQ and amodiaquine (AQ) rose steadily thereafter, reaching more than 30 percent RII/RII failures by the mid 1990s (Muller et al., 2003). CQ resistant P. falciparum likely arose independently in PNG as suggested by observations that the local Pfcrt haplotype is distinct from that in Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America (Mehlotra et al., 2005). P. vivax resistance to CQ was first detected in 1989 (Rieckmann et al., 1989; Schuurkamp et al., 1992; Whitby et al., 1989) but clinical failure rates remained low through the 1990s (Genton et al., 2005). Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) resistant P. falciparum was reported in 1980 (Darlow et al., 1980) when malaria treatment was based on monotherapy with this drug. Despite existing resistance to these various monotherapies, anti-malarial drug efficacy studies conducted in the late 1990s confirmed the high efficacy of SP combined with CQ or AQ (Jayatilaka et al., 2003). Accordingly, in 2000 the first line anti-malarial regimen for treatment of uncomplicated malaria was changed from CQ or AQ alone to CQ plus SP for older children and AQ plus SP for young children. Not surprisingly, parasitological resistance to the combinations rapidly developed (Marfurt et al., 2010).

In a recent clinical trial comparing various combination anti-malarial therapies in PNG children (Karunajeewa et al., 2008), the best clinical and parasitological outcome for treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum was AL: 95.2 percent PCR-corrected day 42 efficacy. The other three regimens examined in this trial showed significantly poorer efficacy: CQ-SP - 81.5 percent, artesunate-SP - 85.4 percent and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHA-PIP) - 88.0 percent. DHA-PIP was however the most efficacious treatment for P. vivax (recurrent parasitaemia was observed among 30.6 percent of recipients versus 64.9 to 87.0 percent for the other regimens). After molecular diagnostic correction for recurrent parasitaemia of the same or differing genotype from that observed at the time of drug administration, DHA-PIP continued to show the best efficacy: 9.7% recurrent parasitemia versus 22.2, 28.1 and 51.4 percent for AL, artesunate-SP and CQ-SP (Barnadas et al., 2011). As a consequence, a recommendation for AL as first-line and DHA-PIP as second line treatment of vivax malaria was made in 2009. Implementation is targeted for 2011.

A significant impediment to controlling and ultimately eliminating malaria in PNG is the ability of P. vivax to relapse from previously dormant liver stage hypnozoites (Mueller et al., 2009a). Optimal treatment of P. vivax should therefore include radical cure of long-lasting liver stages (Wells et al., 2010). The only currently approved drug for elimination of P. vivax (or P. ovale) hypnozoites is primaquine, a drug which can cause hemolysis in persons with severe deficiencies of erythrocyte anti-oxidant enzymes such as G6PD. Moreover, it is currently widespread practice that the drug is taken daily for 14 days (Baird and Hoffman, 2004). The absence of an easily field-deployable diagnostic test for point-of-care screening for G6PD deficiency at low cost (2011b) as well as difficulty in achieving good adherence to a 14-day treatment course are major obstacles to appropriate P. vivax treatment in most endemic areas. The development of the 2010 PNG national standard treatment guidelines reflected these complexities. In line with current World Health Organization recommendations (WHO, 2010), primaquine treatment was until recently not seen as important to PNG policy given the high and stable transmission of P. vivax that favors rapid re-infection. The high burden of recurrent P. vivax parasitemia following treatment with AL in recent drug trials (Barnadas et al., 2011; Karunajeewa et al., 2008), however, convinced policy makers to include an option of treatment with primaquine for blood smear confirmed cases in the recently revised treatment guidelines. Given that G6PD testing is not available in most PNG health facilities and tolerability data for primaquine in young children are lacking, a daily dose of 0.25mg/kg body weight was chosen even though this dose may fail to prevent relapses of local P. vivax strains (Baird, 2009; Baird and Hoffman, 2004; Mueller et al., 2009a). Since G6PD deficiency alleles are common in local populations, the internationally recommended daily dose of 0.5 mg/kg was considered too risky to be implemented without point-of-care G6PD testing.

Given the high priority of developing better anti-hyponzoite therapies and low cost point-of-care G6PD testing (2011a; 2011b; 2011c), research conducted by the ICEMR will study genetic differences between P. vivax obtained before and at various times after drug-mediated cure of parasitemia to draw inferences regarding exposure to newly infective sporozoites versus relapse as the basis for recurrent P. vivax parasitemia and febrile illness.

1.6 Earlier malaria control efforts in PNG

Historically the prevalence of various malaria species in PNG has been greatly affected by public health interventions that were intended to eliminate malaria in the middle of the 20th century. P. vivax was the predominant species before vector control measures such as residual spraying with dichlorodiphenyltricholoroethane (DDT) and dieldrin and mass drug administration with CQ were initiated in the late 1950s. When malaria elimination efforts were abandoned in the late 1970s due to lack of financial resources to continue the program and increasing recognition that elimination was not feasible, P. falciparum superseded P. vivax as the predominant species (Muller et al., 2003). This shift in the predominant malaria species was presumably due to the emergence of CQ resistant P. falciparum (Mueller et al., 2009a) as highlighted by the much greater reduction in the prevalence of P. falciparum than P. vivax in East Sepik Province after the addition of SP to CQ and AQ in 2000 (Kasehagen et al., 2007).

Apart from Madang Province and East Sepik Province (Figure 2) where malaria epidemiology, immunology and vaccine studies have conducted since the 1980s (Alpers et al., 1992; Cattani et al., 1986b; Genton et al., 1995a; Genton et al., 1995b; Lin et al., 2010a; Michon et al., 2007; Mueller et al., 2009b; Muller et al., 2003; Reeder, 2003), data describing the current burden of Plasmodium species infections from other parts of the country are limited. Between 2000 and 2004 cross-sectional surveys of blood stage infection were conducted in a total of 23,301 participants in 118 communities in order to map the extent of malaria transmission in the PNG highlands (Mueller et al., 2002a; Mueller et al., 2004; Mueller et al., 2005; Mueller et al., 2006; Mueller et al., 2007; Mueller et al., 2002b; Muller et al., 2003). Collectively, these surveys showed a strong association between altitude and malaria endemicity (Senn et al., 2010). Malaria was endemic below 1200 meters, although the prevalence decreased as altitude increased. From 1200 to 1600 meters malaria transmission was unstable, and at altitudes greater than 1600 meters there was no transmission. P. falciparum has replaced P. vivax as the most common cause of malaria epidemics in the highlands. As part of the external evaluation of the Global Fund Round 3 support to the PNG national malaria control program, the first national surveys of malaria prevalence in the post-DDT control era were conducted in 2008 and 2009. These data constitute a baseline against which the impact of current malaria control efforts can be evaluated.

1.7 Potential resilience of P. vivax to control and elimination

The malaria control strategy of the PNG National Department of Health includes nationwide distribution of free LLINs and greater availability of diagnosis and treatment through the introduction of ACT, provision of RDTs and strengthening of malaria microscopy. These measures can be expected to result in significant reductions in mosquito-borne transmission, Plasmodium species infection prevalence and malaria morbidity and mortality. However, sustained reduction in malaria transmission may also lead to a decrease in naturally acquired immunity and consequently, a shift in the peak burden of malaria infection and illness to older age groups (Doolan et al., 2009; O’Meara et al., 2008). This scenario may be particularly relevant to areas where transmission has historically been stable and clinical immunity is acquired during childhood. Given the biological differences among the four Plasmodium species endemic in PNG, malaria control efforts may affect individual Plasmodium species differently. In particular, P. vivax with its faster developmental cycle in mosquito vectors, propensity to relapse due to genetically heterogeneous, long-lasting dormant liver stages and production of gametocytes prior to causing symptomatic illness, is likely to be more refractory to the chosen interventions (Mueller et al., 2009a). Accordingly, a relative shift from P. falciparum to P. vivax predominance (or even greater predominance of P. vivax), regardless of the pre-existing level of endemicity, may ensue during the seven-year duration of the SW Pacific ICEMR. A major goal of the ICEMR program is therefore to advance knowledge of how this shift in dominant malaria species and attendant changes in transmission and treatment affect malaria epidemiology and naturally acquired immunity. This will be accomplished by performing prospective cross-sectional community surveys for malaria infection and morbidity and repeated age-structured child cohort studies similar to those that have been conducted previously in Madang Province and East Sepik Province, as discussed below.

1.8 Naturally acquired immunity to P. vivax and P. falciparum

In 2003 and 2004, before malaria control activities supported by the PNG Department of Health were initiated, a study of 206 5 to 14 year old children in the Mugil area of Madang Province characterized the risk of malaria infection and morbidity due to P. vivax and P. falciparum (Cole-Tobian et al., 2007; Michon et al., 2007). Following treatment with artesunate to cure blood stage infection, children were followed actively for clinical illness for six months. Whereas the frequency of re-infection with P. falciparum and P. vivax was similar (Incidence Rate for P. falciparum 5.00 per year versus P. vivax 5.28 per year), symptomatic malaria was 21-times more likely to develop from P. falciparum than P. vivax (respective Incidence Rates 1.17 per year and 0.06 per year) (Michon et al., 2007). Children less than nine years old had a reduced risk of P. vivax blood stage infection of low to moderate density (less than 150 per μL, adjusted Hazard Ratio = 0.42-0.65, p <0.05) whereas for P. falciparum there were similar reductions in the risk of infection only for high-density parasitemia (greater than 5000 per μL, adjusted Hazard Ratio = 0.48, p = 0.002) and symptomatic malaria (adjusted Hazard Ratio = 0.51, p = 0.016). Thus, by nine years of age children had developed nearly complete clinical immunity to P. vivax characterized by tight control of parasite densit, whereas immunity to symptomatic P. falciparum malaria remained incomplete.

In order to determine the burden of Plasmodium spp. infection and illness in a younger age group with a high burden of clinical malaria, a longitudinal cohort study of 264 one to three year old children was performed in 2006 and 2007 in the Ilaita region of East Sepik Province (Lin et al., 2010a). In this cohort, children were actively followed for malaria morbidity every two weeks for 16 months; blood samples were collected every eight weeks to determine prevalence of infection. Over the entire age range these children had similar risks of febrile episodes due to P. falciparum (density greater than 2500 per μL; Incidence Rate 1.9 per child per year) and P. vivax (density greater than 500 per μL; Incidence Rate 1.6 per child per year). However, while the incidence of P. vivax clinical attacks decreased significantly with increasing age (from 2.1 episodes per year for age less than 18 months to 0.6 episodes per year for age equal to and greater than 18 months), the incidence of P. falciparum malaria attacks continued to increase until age 36 months (from 1.1 per year among children less than 18 months to 2.2 per year among children 24-29 months with no further change in the 30-36 month age group). Further, across the entire age range, P. vivax infections were more prevalent and showed less seasonal variation that those due to P. falciparum

The observations from these two cohort studies suggest that clinical immunity to P. vivax malaria starts to develop in the second to third year after birth. This is characterized by an increasing ability to control parasites densities below the pyrogenic threshold and nearly complete clinical immunity after less than five years of exposure to high perennial transmission. On the other hand, clinical immunity to P. falciparum.and control of parasite density with this species does not develop until five to nine years of age. The ICEMR will explore whether distinct immune mechanisms underlie the apparently differing rates of acquiring protection from P. vivax versus P. falciparum infection and morbidity and whether progressive reduction in transmission due to increasing use of LLINs and access to ACT impacts this. A major activity of the ICEMR program will therefore be to perform similar age-structured cohort studies of children in the same areas in order to determine how universal coverage with LLINs and access to ACTs implemented with support from the Global Fund group (Rudge et al., 2010) impact malaria morbidity in this highly susceptible age group.

Highlights.

This section is not applicable to the Special Issue on Malaria Elimination or can be ompleted after acceptance based on instructions from the Editor.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a grant from the United States Public Health Service (NIH/NIAID U19 AI089686).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- A research agenda for malaria eradication: cross-cutting issues for eradication. PLoS medicine. 2011a;8:e1000404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A research agenda for malaria eradication: diagnoses and diagnostics. PLoS medicine. 2011b;8:e1000396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A research agenda for malaria eradication: drugs. PLoS medicine. 2011c;8:e1000402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S, O’Donnell A, Alexander N. Causes of coma in children with malaria in Papua New Guinea. Lancet. 1996a;348:1168–1169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)65301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SJ, O’Donnell A, Alexander ND, Alpers MP, Peto TE, Clegg JB, Weatherall DJ. alpha+-Thalassemia protects children against disease caused by other infections as well as malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14736–14741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SJ, O’Donnell A, Alexander ND, Clegg JB. Severe malaria in children in Papua New Guinea. QJM. 1996b;89:779–788. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.10.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SJ, Raiko A, O’Donnell A, Alexander ND, Clegg JB. Causes of preterm delivery and intrauterine growth retardation in a malaria endemic region of Papua New Guinea. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;79:F135–140. doi: 10.1136/fn.79.2.f135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpers MP, al-Yaman F, Beck HP, Bhatia KK, Hii J, Lewis DJ, Paru R, Smith TA. The Malaria Vaccine Epidemiology and Evaluation Project of Papua New Guinea: rationale and baseline studies. P N G Med J. 1992;35:285–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird JK. Resistance to therapies for infection by Plasmodium vivax. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:508–534. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird JK, Hoffman SL. Primaquine therapy for malaria. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004;39:1336–1345. doi: 10.1086/424663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcus MJ, Basri H, Picarima H, Manyakori C, Sekartuti, Elyazar I, Bangs MJ, Maguire JD, Baird JK. Demographic risk factors for severe and fatal vivax and falciparum malaria among hospital admissions in northeastern Indonesian Papua. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:984–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnadas C, Koepfli C, Karunajeewa HA, Siba PM, Davis TME, Mueller I. Characterization of Treatment Failure in Efficacy Trials of Drugs against Plasmodium vivax by Genotyping Neutral and Drug Resistance-Associated Markers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01552-10. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe NW, Cooper RD, Morrison DA, Ellis JT. A phylogenetic study of the Anopheles punctulatus group of malaria vectors comparing rDNA sequence alignments derived from the mitochondrial and nuclear small ribosomal subunits. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2000;17:430–436. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2000.0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe NW, Saul A. Discrimination of all members of the Anopheles punctulatus complex by polymerase chain reaction--restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:478–481. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet A, Mai A, Bockarie F, Lagog M, Zimmerman P, Alpers MP, Reeder JC, Bockarie MJ. Polymerase chain reaction diagnosis and the changing pattern of vector ecology and malaria transmission dynamics in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabin BJ, Ginny M, Sapau J, Galme K, Paino J. Consequences of maternal anaemia on outcome of pregnancy in a malaria endemic area in Papua New Guinea. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1990;84:11–24. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1990.11812429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce MC, Donnelly CA, Alpers MP, Galinski MR, Barnwell JW, Walliker D, Day KP. Cross-species interactions between malaria parasites in humans. Science. 2000a;287:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce MC, Donnelly CA, Packer M, Lagog M, Gibson N, Narara A, Walliker D, Alpers MP, Day KP. Age- and species-specific duration of infection in asymptomatic malaria infections in Papua New Guinea. Parasitology. 2000b;121(Pt 3):247–256. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099006344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkot TR, Graves PM, Paru R, Wirtz RA, Heywood PF. Human malaria transmission studies in the Anopheles punctulatus complex in Papua New Guinea: sporozoite rates, inoculation rates, and sporozoite densities. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:135–144. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkot TR, Narara A, Paru R, Graves PM, Garner P. Human host selection by anophelines: no evidence for preferential selection of malaria or microfilariae-infected individuals in a hyperendemic area. Parasitology. 1989;98(Pt 3):337–342. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000061400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattani JA. The epidemiology of malaria in Papua New Guinea. In: Attenborough R, Alpers M, editors. Human Biology in Papua New Guinea: The Small Cosmos. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1992. pp. 302–312. [Google Scholar]

- Cattani JA, Gibson FD, Alpers MP, Crane GG. Hereditary ovalocytosis and reduced susceptibility to malaria in Papua New Guinea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:705–709. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattani JA, Moir JS, Gibson FD, Ginny M, Paino J, Davidson W, Alpers MP. Small-area variations in the epidemiology of malaria in Madang Province. P N G Med J. 1986a;29:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattani JA, Tulloch JL, Vrbova H, Jolley D, Gibson FD, Moir JS, Heywood PF, Alpers MP, Stevenson A, Clancy R. The epidemiology of malaria in a population surrounding Madang, Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986b;35:3–15. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn IA, Mackinnon MJ, O’Donnell A, Allen SJ, Moulds JM, Baisor M, Bockarie M, Reeder JC, Rowe JA. A human complement receptor 1 polymorphism that reduces Plasmodium falciparum rosetting confers protection against severe malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:272–277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305306101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole-Tobian JL, Michon P, Dabod E, Mueller I, King CL. Dynamics of asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax infections and Duffy binding protein polymorphisms in relation to parasitemia levels in Papua New Guinean children. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2007;77:955–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RD, Waterson DG, Frances SP, Beebe NW, Pluess B, Sweeney AW. Malaria vectors of Papua New Guinea. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:1495–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RD, Waterson DGE, Frances SP, Beebe NW, Sweeney AW. Speciation and distribution of members of the Anopheles punctulatus (Diptera: Cuclicidae) group in Papua New Guinea. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:16–27. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlow B, Vrbova H, Stace J, Heywood P, Aalpers M. Fansidar-resistant falciparum malaria in Papua New Guinea. Lancet. 1980;2:1243. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desowitz RS, Alpers MP. Placental Plasmodium falciparum parasitaemia in East Sepik (Papua New Guinea) women of different parity: the apparent absence of acute effects on mother and foetus. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;86:95–102. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1992.11812638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolan DL, Dobano C, Baird JK. Acquired immunity to malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:13–36. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00025-08. Table of Contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke T, Michael A, Mgone J, Frank D, Wal T, Sehuko R. Etiology of child mortality in Goroka, Papua New Guinea: a prospective two-year study. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:16–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowkes FJ, Michon P, Pilling L, Ripley RM, Tavul L, Imrie HJ, Woods CM, Mgone CS, Luty AJ, Day KP. Host erythrocyte polymorphisms and exposure to Plasmodium falciparum in Papua New Guinea. Malar J. 2008;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genton B, al-Yaman F, Beck HP, Hii J, Mellor S, Narara A, Gibson N, Smith T, Alpers MP. The epidemiology of malaria in the Wosera area, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea, in preparation for vaccine trials. I. Malariometric indices and immunity. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1995a;89:359–376. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1995.11812965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genton B, al-Yaman F, Beck HP, Hii J, Mellor S, Rare L, Ginny M, Smith T, Alpers MP. The epidemiology of malaria in the Wosera area, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea, in preparation for vaccine trials. II. Mortality and morbidity. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1995b;89:377–390. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1995.11812966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genton B, al-Yaman F, Mgone CS, Alexander N, Paniu MM, Alpers MP, Mokela D. Ovalocytosis and cerebral malaria. Nature. 1995c;378:564–565. doi: 10.1038/378564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genton B, Baea K, Lorry K, Ginny M, Wines B, Alpers MP. Parasitological and clinical efficacy of standard treatment regimens against Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax and P. malariae in Papua New Guinea. PNG Med J. 2005;48:141–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genton B, D’Acremont V, Rare L, Baea K, Reeder JC, Alpers MP, Muller I. Plasmodium vivax and mixed infections are associated with severe malaria in children: a prospective cohort study from Papua New Guinea. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmond TR, Donovan KO, Riley ID. Chloroquine resistant malaria in Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 1976;19:184–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay SI, Snow RW. The malaria Atlas Project: developing global maps of malaria risk. PLoS medicine. 2006;3:e473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hii JL, Smith T, Mai A, Mellor S, Lewis D, Alexander N, Alpers MP. Spatial and temporal variation in abundance of Anopheles (Diptera:Culicidae) in a malaria endemic area in Papua New Guinea. J Med Entomol. 1997;34:193–205. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AV, Bowden DK, O’Shaughnessy DF, Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. Beta thalassemia in Melanesia: association with malaria and characterization of a common variant (IVS-1 nt 5 G----C) Blood. 1988;72:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayatilaka KD, Taviri J, Kemiki A, Hwaihwanje I, Bulungol P. Therapeutic efficacy of chloroquine or amodiaquine in combination with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 2003;46:125–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunajeewa HA, Mueller I, Senn M, Lin E, Law I, Gomorrai PS, Oa O, Griffin S, Kotab K, Suano P, Tarongka N, Ura A, Lautu D, Page-Sharp M, Wong R, Salman S, Siba P, Ilett KF, Davis TM. A trial of combination antimalarial therapies in children from Papua New Guinea. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2545–2557. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasehagen LJ, Mueller I, Kiniboro B, Bockarie MJ, Reeder JC, Kazura JW, Kastens W, McNamara DT, King CH, Whalen CC, Zimmerman PA. Reduced Plasmodium vivax erythrocyte infection in PNG Duffy-negative heterozygotes. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasehagen LJ, Mueller I, McNamara DT, Bockarie MJ, Kiniboro B, Rare L, Lorry K, Kastens W, Reeder JC, Kazura JW, Zimmerman PA. Changing patterns of Plasmodium blood-stage infections in the Wosera region of Papua New Guinea monitored by light microscopy and high throughput PCR diagnosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:588–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampah DA, Yeo TW, Hardianto SO, Tjitra E, Kenangalem E, Sugiarto P, Price RN, Anstey NM. Coma Associated with Microscopy-Diagnosed Plasmodium vivax: A Prospective Study in Papua, Indonesia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann D. Demography and causes of death among the Huli in the Tari Basin. P N G Med J. 2002;45:51–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann D, Howard P, Heywood P. Nutrition and morbidity: acute lower respiratory tract infections, diarrhoea and malaria. P N G Med J. 1988;31:109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin E, Kiniboro B, Gray L, Dobbie S, Robinson L, Laumaea A, Schopflin S, Stanisic D, Betuela I, Blood-Zikursh M, Siba P, Felger I, Schofield L, Zimmerman P, Mueller I. Differential patterns of infection and disease with P. falciparum and P vivax in young Papua New Guinean children. PLoS One. 2010a;5:e9047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin E, Michon P, Richards JS, Tavul L, Dabod E, Beeson JG, King C, Zimmerman PA, Mueller I. Minimal association of common red blood cell polymorphisms with P. falciparum infection and uncomplicated malaria in Papua New Guinean children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010b;83:828–833. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfurt J, Smith TA, Hastings IM, Muller I, Sie A, Oa O, Baisor M, Reeder JC, Beck HP, Genton B. Plasmodium falciparum resistance to anti-malarial drugs in Papua New Guinea: evaluation of a community-based approach for the molecular monitoring of resistance. Malar J. 2010;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlotra RK, Kasehagen LJ, Baisor M, Lorry K, Kazura JW, Bockarie MJ, Zimmerman PA. Malaria infections are randomly distributed in diverse holoendemic areas of Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:555–562. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlotra RK, Lorry K, Kastens W, Miller SM, Alpers MP, Bockarie M, Kazura JW, Zimmerman PA. Random distribution of mixed species malaria infections in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:225–231. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlotra RK, Mattera G, Bhatia K, Reeder JC, Stoneking M, Zimmerman PA. Insight into the early spread of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum infections in Papua New Guinea. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:2174–2179. doi: 10.1086/497694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mgone CS, Koki G, Paniu MM, Kono J, Bhatia KK, Genton B, Alexander ND, Alpers MP. Occurrence of the erythrocyte band 3 (AE1) gene deletion in relation to malaria endemicity in Papua New Guinea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:228–231. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michon P, Cole-Tobian JL, Dabod E, Schoepflin S, Igu J, Susapu M, Tarongka N, Zimmerman PA, Reeder JC, Beeson JG, Schofield L, King CL, Mueller I. The risk of malarial infections and disease in Papua New Guinean children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:997–1008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller I, Galinski MR, Baird JK, Carlton JM, Kochar DK, Alonso PL, del Portillo HA. Key gaps in the knowledge of Plasmodium vivax, a neglected human malaria parasite. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009a;9:555–566. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70177-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller I, Kaiok J, Reeder JC, Cortes A. The population structure of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax during an epidemic of malaria in the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002a;67:459–464. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller I, Kundi J, Bjorge S, Namuigi P, Saleu G, Riley ID, Reeder JC. The epidemiology of malaria in the Papua New Guinea highlands: 3. Simbu Province. P N G Med J. 2004;47:159–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller I, Namuigi P, Kundi J, Ivivi R, Tandrapah T, Bjorge S, Reeder JC. Epidemic malaria in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:554–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller I, Ousari M, Yala S, Ivivi R, Sie A, Reeder JC. The epidemiology of malaria in the Papua New Guinea highlands: 4. Enga Province. P N G Med J. 2006;49:115–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller I, Rogerson S, Mola GD, Reeder JC. A review of the current state of malaria among pregnant women in Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 2008;51:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller I, Sie A, Ousari M, Iga J, Yala S, Ivivi R, Reeder JC. The epidemiology of malaria in the Papua New Guinea highlands: 5. Aseki, Menyamya and Wau-Bulolo, Morobe Province. P N G Med J. 2007;50:111–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller I, Taime J, Ibam E, Kundi J, Lagog M, Bockarie M, Reeder JC. Complex patterns of malaria epidemiology in the highlands region of Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 2002b;45:200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller I, Widmer S, Michel D, Maraga S, McNamara DT, Kiniboro B, Sie A, Smith TA, Zimmerman PA. High sensitivity detection of Plasmodium species reveals positive correlations between infections of different species, shifts in age distribution and reduced local variation in Papua New Guinea. Malar J. 2009b;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller I, Bockarie M, Alpers M, Smith T. The epidemiology of malaria in Papua New Guinea. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:253–259. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell A, Allen SJ, Mgone CS, Martinson JJ, Clegg JB, Weatherall DJ. Red cell morphology and malaria anaemia in children with Southeast-Asian ovalocytosis band 3 in Papua New Guinea. Br J Haematol. 1998;101:407–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara WP, Bejon P, Mwangi TW, Okiro EA, Peshu N, Snow RW, Newton CR, Marsh K. Effect of a fall in malaria transmission on morbidity and mortality in Kilifi, Kenya. Lancet. 2008;372:1555–1562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61655-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SS, Mehlotra RK, Kastens W, Mgone CS, Kazura JW, Zimmerman PA. The association of the glycophorin C exon 3 deletion with ovalocytosis and malaria susceptibility in the Wosera, Papua New Guinea. Blood. 2001;98:3489–3491. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poespoprodjo JR, Fobia W, Kenangalem E, Lampah DA, Hasanuddin A, Warikar N, Sugiarto P, Tjitra E, Anstey NM, Price RN. Vivax malaria: a major cause of morbidity in early infancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1704–1712. doi: 10.1086/599041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff A, Siswantoro H, Kenangalem E, Maristela R, Wuwung RM, Laihad F, Ebsworth EP, Anstey NM, Tjitra E, Price RN. Two fixed-dose artemisinin combinations for drug-resistant falciparum and vivax malaria in Papua, Indonesia: an open-label randomised comparison. Lancet. 2007a;369:757–765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60160-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff A, Siswantoro H, Kenangalem E, Wuwung M, Brockman A, Edstein MD, Laihad F, Ebsworth EP, Anstey NM, Tjitra E, Price RN. Therapeutic response of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in southern Papua, Indonesia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007b;101:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder JC. Health research in Papua New Guinea. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:241–245. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann KH, Davis DR, Hutton DC. Plasmodium vivax resistance to chloroquine? Lancet. 1989;2:1183–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91792-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudge JW, Phuanakoonon S, Nema KH, Mounier-Jack S, Coker R. Critical interactions between Global Fund-supported programmes and health systems: a case study in Papua New Guinea. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(Suppl 1):i48–52. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurkamp GJ, Spicer PE, Kereu RK, Bulungol PK, Rieckmann KH. Chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax in Papua New Guinea. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1992;86:121–122. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90531-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn N, Maraga S, Sie A, Rogerson SJ, Reeder JC, Siba P, Mueller I. Population hemoglobin mean and anemia prevalence in Papua New Guinea: new metrics for defining malaria endemicity? PLoS One. 2010;5:e9375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serjeantson SW, Board PG, Bhatia KK. Population Genetics in Papua New Guinea: A prespective on Human Evolution. In: Attenborough RD, Alpers MP, editors. Human Biology in Papua New Guinea: The Small Cosmos. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1992. pp. 198–233. [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Genton B, Baea K, Gibson N, Narara A, Alpers MP. Prospective risk of morbidity in relation to malaria infection in an area of high endemicity of multiple species of Plasmodium. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001a;64:262–267. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Hii JL, Genton B, Muller I, Booth M, Gibson N, Narara A, Alpers MP. Associations of peak shifts in age--prevalence for human malarias with bednet coverage. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001b;95:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanisic DI, Mueller I, Betuela I, Siba P, Schofield L. Robert Koch redux: malaria immunology in Papua New Guinea. Parasite Immunol. 2010;32:623–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2010.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B. Observations on malaria vectors of the Anopheles punctulatus complex in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate. J Med Entomol. 1975;11:677–687. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/11.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjitra E, Anstey NM, Sugiarto P, Warikar N, Kenangalem E, Karyana M, Lampah DA, Price RN. Multidrug-resistant Plasmodium vivax associated with severe and fatal malaria: a prospective study in Papua, Indonesia. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk WJOM, Parkinson AD. Epidemiology of malaria in New Guinea. PNG Med J. 1974;17:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wells TN, Burrows JN, Baird JK. Targeting the hypnozoite reservoir of Plasmodium vivax: the hidden obstacle to malaria elimination. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitby M, Wood G, Veenendaal JR, Rieckmann K. Chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax. Lancet. 1989;2:1395. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. second edition. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yenchitsomanus P, Summers KM, Chockkalingam C, Board PG. Characterization of G6PD deficiency and thalassaemia in Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Medical Journal. 1986;29:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AP, Bennett NM. Chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria acquired in Papua New Guinea. Med J Aust. 1976;2:845. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1976.tb115417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman PA, Patel SS, Maier AG, Bockarie MJ, Kazura JW. Erythrocyte polymorphisms and malaria parasite invasion in Papua New Guinea. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:250–252. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman PA, Woolley I, Masinde GL, Miller SM, McNamara DT, Hazlett F, Mgone CS, Alpers MP, Genton B, Boatin BA, Kazura JW. Emergence of FY*A(null) in a Plasmodium vivax-endemic region of Papua New Guinea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13973–13977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]