Abstract

Background/Aims

Genetic variants that affect estrogen activity may influence the risk of Alzheimer's disease (AD). We examined the relation of polymorphisms in the gene for the estrogen receptor-beta (ESR2) to the risk of AD in women with Down syndrome.

Methods

Two hundred and forty-nine women with Down syndrome, 31–70 years of age and nondemented at baseline, were followed at 14- to 18-month intervals for 4 years. Women were genotyped for 13 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the ESR2 gene, and their association with AD incidence was examined.

Results

Among postmenopausal women, we found a 2-fold increase in the risk of AD for women carrying 1 or 2 copies of the minor allele at 3 SNPs in introns seven (rs17766755) and six (rs4365213 and rs12435857) and 1 SNP in intron eight (rs4986938) of ESR2.

Conclusion

These findings support a role for estrogen and its major brain receptors in modulating susceptibility to AD in women.

Key Words: Estrogen, Estrogen receptor-beta, Down syndrome, Alzheimer's disease

Introduction

Experimental and epidemiologic studies have shown that estrogen has neuroprotective effects and that loss of estrogen after menopause may contribute to the cognitive declines associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD) in women [1]. The neuroprotective mechanisms of estrogen include increases in cholinergic activity [2,3,4], antioxidant activity [5] and protection against the neurotoxic effects of beta amyloid [6]. Therefore, factors that influence estrogen activity may also influence vulnerability to AD, including an allelic variation in genes within the estrogen biosynthesis and estrogen receptor pathways.

Estrogen exerts many of its effects through the activation of nuclear receptors which are expressed in multiple tissues [7]. In the brain, two estrogen receptors, ER-α and ER-β, encoded by two different genes, ESR1 and ESR2, have been identified and have been found in regions affected by AD, including the hippocampus, basal forebrain and amygdala [8,9]. ER-α and ER-β differ in tissue distribution [10], with ER-β expression being more predominant than ER-α in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, anterior olfactory nucleus, dorsal raphe, substantia nigra, midbrain ventral tegmental area and cerebellum [8,11,12], suggesting that ER-β may play a role in memory and the risk for AD [13]. Both ER-α and ER-β appear to have a role in the preservation of cholinergic activity [14,15], and ER-β may mediate the effects of estrogen on hippocampal synaptic plasticity [13]. While a number of studies have examined the relation of AD to variants in ESR1[16,17,18,19,20,21,22], or to genes in the estrogen biosynthetic pathway [23,24,25,26,27], fewer studies have investigated variants in the ESR2 gene and the findings have been less consistent [28,29,30,31,32,33].

Women with Down syndrome (DS) have an early onset of menopause [34] and a high risk for AD, with onset of dementia 10–20 years earlier than women in the general population [35,36,37]. Brain levels of beta amyloid peptides are high from an early age [38], likely due, at least in part, to the triplication and overexpression of the gene for amyloid precursor protein located on chromosome 21 [39]. Women with DS with earlier onset of menopause have an earlier onset of AD than women with later onset of menopause [40], and postmenopausal women with low levels of bioavailable estradiol have both an earlier onset and an increased cumulative incidence of AD than postmenopausal women with high levels of bioavailable estradiol [41]. These findings suggest that reductions in estrogen following menopause may contribute to the cascade of pathological processes leading to AD in this high-risk population. Women with DS carrying the P allele at PvuII in ESR1 have a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of AD compared with those carrying the p allele [22]. In this study, we examined the relationships between SNPs in ESR2 and the risk for AD in a community-based cohort of women with DS.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The initial cohort included a community-based sample of 279 women with DS. Of these 279 women, 252 (90.3%) agreed to provide a blood sample and were genotyped for ESR2. All individuals were 30 years of age or older at study onset and resided in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania or Connecticut. In all cases a family member or correspondent provided informed consent (for blood sampling and genotyping included) with participants providing assent. The participation rate was 74.6%. The distribution of the level of intellectual disability and residential placement did not differ between participants and those who did not participate. Recruitment, informed consent and study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University Medical Center and the New York State Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities.

Clinical Assessment

Assessments were repeated at 14- to 18-month intervals over five cycles of data collection and included evaluations of cognition and functional abilities, behavioral/psychiatric conditions and health status. Cognitive function was evaluated with a test battery designed for use with individuals with DS varying widely in their levels of intellectual functioning, as described previously [42]. Structured interviews were conducted with caregivers to collect information on changes in cognition, function, adaptive behavior and medical status. The past and current medical records of all participants were reviewed.

Menopausal Status

Menopausal status was ascertained through menstrual charts in medical records, by medical record review, interviews with caregivers and family members and a survey of primary care physicians and gynecologists. The medical records included menstrual charts documenting the date and duration of menses. The correlations between age at menopause ascertained from the different sources were substantial, suggesting that ascertainment of age at menopause was reliable. The correlation between age at menopause ascertained from medical records (including menstrual charts) and from the physician survey was 0.99, the correlation ascertained from medical records and from informant interviews was 0.77 and the correlation ascertained from the physician survey and from informant interviews was 0.80. The mean difference in age at menopause from the different sources ranged from 0.21 years for the difference ascertained from medical charts and the physician survey to 0.38 years for the difference ascertained from medical charts and informant interviews. We used a consensus age at menopause, with greater weight given to that ascertained from medical records, followed by that from the physician survey, then that from informant interviews. In keeping with convention, we classified age at natural menopause as the age at the last menstrual period preceding cessation of menses for 12 months, in the absence of known causes of amenorrhea (e.g. surgery). The median age at menopause was 46.0 years (range 35–52). We were able to ascertain menopausal status for 248 of the 252 participants with ESR2 genotypes (99%). The 4 women with unknown menopausal status were excluded from all analyses. Among the 248 participants with known menopausal status, 146 were postmenopausal, 78 were premenopausal and 21 were perimenopausal. Three women had never menstruated and were excluded, leaving 245 women for analysis.

Classification of Dementia

The classification of dementia status, dementia subtype and age at onset was determined during clinical consensus conferences where information from all available sources was reviewed. Classifications were made blind to ESR2 genotype or information on menopausal status or hormone levels. We classified participants into 2 groups, following the recommendations of the AAMR-IASSID Working Group for the Establishment of Criteria for the Diagnosis of Dementia in Individuals with Developmental Disability [43]. Participants were classified as nondemented if they were without cognitive or functional decline, or if they showed some cognitive and/or functional decline that was not of significant magnitude to meet dementia criteria (n = 173). Participants were classified as demented if they showed a substantial and consistent decline over the course of follow-up (of a duration of at least one year) and if they had no other medical or psychiatric conditions that might mimic dementia (n = 72). The age at meeting the criteria for dementia was used to estimate the age at the onset of dementia. Only participants with probable or possible AD were included in the analysis. Of the 146 postmenopausal women, 79 were nondemented and 67 had possible or probable AD.

DNA Isolation and Genotyping

Women who provided a blood sample were karyotyped. We were able to karyotype all but 12 of the 245 participants in this study (95.1%). We found low-level mosaicism (3–15%) in 6 women (2.6%). Their ages were 51, 51, 56, 58, 61 and 68 years. One 43-year-old woman had a high level of mosaicism and mosaic DS was noted in her medical chart. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes, using the FlexiGene DNA kit (Qiagen). Isolation of DNA and genotyping were performed blind to the dementia status of the participant. SNPs reported to be associated with estrogen-related disorders (breast cancer, osteoporosis) and prior studies of AD were selected. Additional SNPs were selected to provide coverage of the gene. We analyzed 13 SNPs in ESR2, 12 of which are within introns of the gene, and the remaining 1 in exon nine (see table 2). SNPs were genotyped using TaqMan® PCR assays (Applied Biosystems) with PCR cycling conditions recommended by the manufacturer, and by PreventionGenetics using proprietary array tape technology. Accuracy of the genotyping (>97%) was verified by including duplicate DNA samples, by comparing the TaqMan and array tape data with the results of restriction digestion polymorphisms/restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) for several of the SNPs, and by testing for the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Table 2.

ESR2 SNP chromosome locationa

| SNPs | Chromosome position | Distance from previous SNP | MA | MAF (NCBI) | MAF (DS) | SNP location relative to ESR2 (isoform 2 transcript) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1255998 | 63763624 | C | 0.086 | 0.113 | exon 9 | |

| rs1256065 | 63768685 | 5,061 | C | 0.429 | 0.394 | intron 8 |

| rs4986938 | 63769569 | 884 | T | 0.381 | 0.442 | intron 8 |

| rs867443 | 63770795 | 1,226 | A | 0.308 | 0.305 | intron 8 |

| rs1256061 | 63773346 | 2,551 | T | 0.475 | 0.493 | intron 7 |

| rs1256059 | 63780170 | 6,824 | A | 0.416 | 0.382 | intron 7 |

| rs17766755 | 63785526 | 5,356 | A | 0.332 | 0.426 | intron 7 |

| rs4365213 | 63790017 | 4,491 | G | 0.428 | 0.496 | intron 6 |

| rs12435857 | 63793278 | 3,261 | A | 0.438 | 0.496 | intron 6 |

| rs1256043 | 63804035 | 10,757 | A | 0.321 | 0.380 | intron 4 |

| rs7154455 | 63806413 | 2,378 | C | 0.314 | 0.37 | intron 3 |

| rs1256039 | 63808732 | 2,319 | G | 0.400 | 0.388 | intron 3 |

| rs1256030 | 63816923 | 8,191 | A | 0.417 | 0.412 | intron 2 |

MA = Minor allele; MAF = minor allele frequency

Physical position on chromosome: Hgl8, March 2006 assembly dbSNP build 130.

Apolipoprotein E Genotypes

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping was carried out by PCR/RFLP analysis using HhaI (CfoI) digestion of an APOE genomic PCR product spanning the polymorphic (cys/arg) sites at codons 112 and 158, followed by acrylamide gel electrophoresis to document the restriction fragment sizes [44]. Participants were classified according to the presence or absence of at least one APOE ∊4 allele.

Potential Confounders

Potential confounders included the presence of an APOE ∊4 allele, level of intellectual disability, body mass index (BMI) and ethnicity. Level of intellectual disability was classified as mild-to-moderate (IQ 35–70) or severe-to-profound (IQ <34), based on IQ scores obtained before the onset of AD. BMI was measured at each evaluation; its baseline measure was used in the analysis and was included as a continuous variable. Ethnicity was categorized as white or nonwhite.

Statistical Analyses

Prior to association analysis, we tested all SNPs for the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium using the Haploview program [45] and all were found to be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. SNPs were analyzed using a dominant model, in which participants homozygous for the common allele were used as the reference group. In preliminary analyses, the χ2 test (or the Fisher exact test when any cell had <5 subjects) was employed to assess the association between AD and SNP genotypes as well as other possible risk factors for AD including ethnicity, level of intellectual disability and the presence of an APOE ∊4 allele. Analysis of variance was used to examine BMI, age and AD status. We used a Cox proportional hazards model to assess the relationship between ESR2 genotypes and age at the onset of AD, adjusting for ethnicity, BMI, level of intellectual disability and the presence of an APOE ∊4 allele. The time to event variable was the age at onset for participants who developed AD and the age at the last assessment for participants who remained nondemented throughout the follow-up period. Because a set of 3 contiguous SNPs that span 7.8 kb – rs17766755, rs4365213 and rs12435857 – were significantly associated with AD in postmenopausal women, we performed a haplotype analysis to identify haplotype(s) that may harbor a susceptibility variant(s) as implemented in the PLINK program [46]. For nearly all individuals, we were able to identify the most likely haplotypes from the genotype data with a high degree of certainty (i.e. the posterior probability approaching 1.0 for most cases with the rest exceeding probability >0.7). Subsequently, we used the estimated haplotypes as a ‘super-locus’ (analogous to a microsatellite marker) to perform a Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The mean age of participants at baseline was 48.9 years (range 31.4–70.1 years) and 88% of the cohort was white. The mean length of follow-up was 4.2 years. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants according to AD status. For the total group at baseline, participants with AD were significantly older than nondemented participants (53.9 vs. 46.8 years) and were more likely to have a severe or profound level of intellectual disability (52.8 vs. 35.3%), but did not differ in the distribution of ethnicity, the frequency of the APOE ∊4 allele or mean level of BMI. The mean age at onset of AD was 54.7 ± 5.1 years. Among postmenopausal women, participants with AD were significantly older than women who remained nondemented throughout the follow-up period (54.3 vs. 51.7 years), but did not differ from nondemented women in the distribution of level of intellectual disability, ethnicity, the frequency of the APOE ∊4 allele or mean BMI.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | All women |

Postmenopausal women |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nondemented | AD | nondemented | AD | |

| Number | 173 | 72 | 79 | 67 |

| Age at baseline (mean ± SD)∗∗ | 46.8 ± 6.7 | 53.9 ± 7.0 | 51.7 ± 6.0 | 54.3 ± 7.1 |

| Level of intellectual disability, n (%)∗∗ | ||||

| mild/moderate | 112 (63.6) | 34 (46.6) | 37 (46.8) | 32 (47.8) |

| severe/profound | 61 (35.3) | 38 (52.8) | 42 (53.2) | 35 (52.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Nonhispanic white | 149 (86.1) | 66 (91.7) | 68 (86.1) | 62 (91.5) |

| Nonwhite | 24 (13.9) | 6 (8.3) | 11 (13.9) | 5 (7.5) |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 29.8 ± 7.0 | 28.2 ± 6.1 | 28.2 ± 6.0 | 27.9 ± 6.3 |

| APOE ε4 allele, n (%) | 38 (22.5) | 19 (26.4) | 16 (20.3) | 17 (25.4) |

p<0.05.

Analysis of SNPS in ESR2

Table 2 shows the locations and minor allele frequencies of ESR2 SNPs for Hapmap whites at the NCBI SNP website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP) and for our cohort of women with DS. Allele frequencies were similar in women with DS to those observed in women without DS in the general population. Table 3 presents the distributions of ESR2 genotypes and the association between ESR2 SNPs and the hazard ratio (HR) for AD among the total group and among postmenopausal women only. In the total group, women who carried 1 or 2 copies of the A allele at rs17766755 were significantly more likely to develop AD, after adjusting for age, ethnicity, level of intellectual disability, BMI and the presence of an APOE ∊4 allele (HR = 1.8, 95% CI 1.0–3.2) (table 3).

Table 3.

AD risk by ESR2 genotype in women with DS∗

| ESR2 Genotype | All women |

Postmenopausal women |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | AD, n (%) | HR∗ (95% CI) | n | AD, n (%) | HR∗ (95% CI) | |

| rs1255998 | ||||||

| CG/CC | 38 | 13 (27.1) | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | 30 | 12 (40.0) | 0.98 (0.5–1.9) |

| GG | 177 | 55 (31.1) | 1.0 (reference) | 114 | 55 (48.2) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs1256065 | ||||||

| AC/CC | 163 | 46 (28.2) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 91 | 41 (45.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) |

| AA | 78 | 22 (28.2) | 1.0 (reference) | 48 | 21 (43.8) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs4986938∗ | ||||||

| CT/TT | 160 | 50 (31.3) | 1.6 (0.9–2.8) | 101 | 49 (48.5) | 1.9 (1.01–3.4) |

| CC | 70 | 18 (25.7) | 1.0 (reference) | 45 | 18 (40.0) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs867443 | ||||||

| AG/AA | 115 | 35 (30.4) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 68 | 34 (50.0) | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) |

| GG | 126 | 37 (29.4) | 1.0 (reference) | 72 | 32 (44.4) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs1256061 | ||||||

| GT/TT | 172 | 55 (32.0) | 1.5 (0.8–2.8) | 113 | 55 (48.7) | 1.8 (0.9–3.6) |

| G | 58 | 13 (22.4) | 1.0 (reference) | 33 | 12 (36.4) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs1256059 | ||||||

| AG/AA | 153 | 44 (28.8) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 94 | 44 (46.8) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) |

| GG | 75 | 24 (32.9) | 1.0 (reference) | 51 | 23 (45.1) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs17766755∗ | ||||||

| AG/AA | 150 | 50 (33.3) | 1.8 (1.0–3.2) | 95 | 49 (51.6) | 2.3 (1.2–4.3) |

| GG | 74 | 15 (20.3) | 1.0 (reference) | 44 | 14 (31.8) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs4365213∗ | ||||||

| AG/GG | 180 | 55 (30.6) | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 107 | 53 (49.5) | 1.9 (1.01–3.8) |

| AA | 66 | 17 (25.8) | 1.0 (reference) | 35 | 13 (37.1) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs12435857∗ | ||||||

| AG/AA | 166 | 54 (32.5) | 1.7 (0.9–3.1) | 110 | 54 (49.1) | 2.1 (1.1–4.2) |

| GG | 63 | 13 (20.6) | 1.0 (reference) | 36 | 12 (34.4) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs1256043 | ||||||

| AG/AA | 152 | 43 (28.3) | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | 92 | 43 (46.7) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) |

| GG | 77 | 25 (32.5) | 1.0 (reference) | 53 | 24 (45.3) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs7154455 | ||||||

| GC/CC | 146 | 42 (28.8) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 82 | 39 (47.6) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) |

| GG | 103 | 31 (30.1) | 1.0 (reference) | 63 | 28 (44.4) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs1256039 | ||||||

| CG/GG | 164 | 47 (28.7) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 93 | 42 (45.2) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) |

| CC | 81 | 25 (30.9) | 1.0 (reference) | 52 | 24 (46.2) | 1.0 (reference) |

| rs1256030 | ||||||

| AG/AA | 178 | 51 (28.7) | 0.9 (0.501.5) | 98 | 46 (46.9) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) |

| GG | 70 | 22 (31.4) | 1.0 (reference) | 46 | 21 (45.7) | 1.0 (reference) |

Not all markers were available for every participant. We used a Cox proportional hazards model, adjusted for age, ethnicity, the level of intellectual disability, baseline BMI and the presence of the APOE e4 allele.

p<0.05

Because there were only 5 cases of AD among premenopausal or perimenopausal women, we repeated the analyses, restricting the sample to postmenopausal women. Among postmenopausal women, those who carried at least 1 copy of the T allele at rs4986938 were twice as likely to develop AD as those with the CC genotype. Three contiguous SNPs located approximately 16kb away from rs4986938 were significantly associated with AD. Specifically, carriers of the A allele at rs17766755, the G allele at rs4365213 and the A allele at rs12435857 had a 2.0-fold increase in the hazard rate compared with women carrying no copies of these alleles (HR for rs4986938 (CT or TT) = 1.9, 95% CI 1.01–3.4; HR for rs17766755 (AG or AA) = 2.3, 95% CI 1.2–4.3; HR for rs4365213 (AG or GG) = 1.9, 95% CI 1.03–3.8; HR for rs12435857 (AG or AA) = 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–4.2) (table 3). These results were unchanged when the analysis was repeated among those without an APOE ∊4 allele (data not shown).

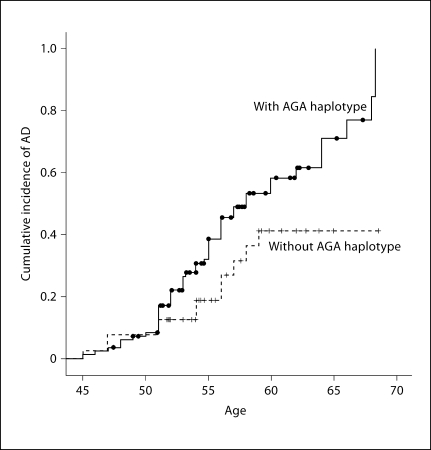

Haplotype Analysis of the Three SNPs in a Cox Proportional Hazards Model

We first computed the most likely haplotypes for each individual, and then used the haplotypes as a ‘super-locus’ to estimate HRs, controlling for potential confounders. Our haplotype analysis using rs17766755-rs4365213-rs12435857 revealed that the carriers of haplotype AGA had an earlier onset and were twice as likely as noncarriers to develop AD after adjusting for the presence of an APOE ∊4 allele level of intellectual disability, ethnicity and BMI (HR = 2.15, 95% CI 1.13–4.11) (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence of AD in women with AGA haplotype DS.

Discussion

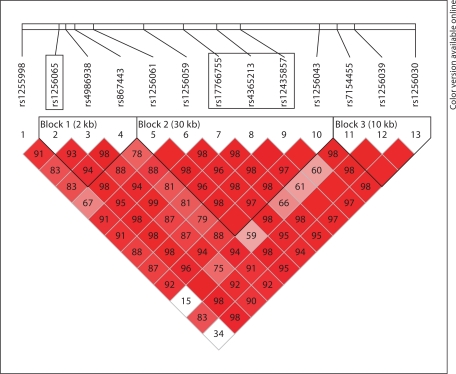

Four SNPs in ESR2 were associated with an increased risk of AD, independent of APOE genotype. Among postmenopausal women, those who carried at least 1 copy of the T allele at rs4986938 were twice as likely to develop AD than those who carried the CC genotype. In addition, approximately 16kb away from rs4986938, a set of 3 contiguous SNPs was significantly associated with AD; these 3 SNPs were located within one haplotype block spanning approximately 7.8 kb (fig. 2). Women with DS who carried the A allele at rs17766755, the G allele at rs4365213 or the A allele at rs12435857 had a 2-fold increased risk of AD, compared with women without these risk alleles. A haplotype-based Cox proportional hazards model continued to support that AGA carriers had a 2-fold risk of developing AD after adjusting for covariates.

Fig. 2.

Linkage disequilibrium patterns for SNPs in ESR2.

The association of these SNPs with an increased risk of AD was seen only among postmenopausal women. Among premenopausal or perimenopausal women, there were 5 who developed AD, 4 who were perimenopausal at baseline and 1 who was still menstruating at baseline. The mean age of the women who were premenopausal or perimenopausal was 42.9 (± 4.0) years; many of these women carrying high-risk alleles may have been too young to develop AD, attenuating the estimate of risk in the total group.

Polymorphisms or haplotypes in ESR2 have been associated with an increased risk for a number of estrogen-related disorders, including osteoporosis [47,48,49,50,51], breast cancer, ovarian cancer [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] and polycystic ovarian disease [61]. ER-β is found in high concentrations in the hippocampus [51], and its activation has been linked to synaptic plasticity and hippocampal-dependent cognition [13,62]. Ovariectomized female Esr2–/– knockout mice perform worse than wild-type mice in a spatial learning task and fail to show improvements in learning and memory when treated with estradiol [13,62], suggesting that the effects of estrogen on hippocampal plasticity and memory may be mediated through ER-β [13]. ER-β can couple to rapid signaling events and is required for estrogen-mediated neuroprotection [63]. Thus, variants in ESR2 may influence cognition via a number of different pathways, including modification of hormone levels, changes in gene activity or changes in gene expression. However, specific pathways through which SNP activity modifies receptor function have not yet been identified.

Previous studies of the relationships of polymorphisms in ESR2 to the risk of AD have found a number of different SNPs to be associated with both increased and decreased risk. In 2 studies, SNPs in ESR2 (rs1256065, rs1271573 and rs1256043) were associated with an increased risk for cognitive impairment or AD in women but not in men [29,64], or were associated with an increased risk in men but not in women (rs1255998) [64]. Another study found a cystosine-adenine repeat in ESR2 that was more strongly protective in men than in women [28], and the Health ABC study found 1 SNP on ESR2 (rs1256030) that was associated with the development of cognitive impairment among both men and women [64]. A diplotype including rs4986938 in the 3′ UTR region of ESR2 has been associated with the risk for AD in both men and women [31], and rs4986938 has been associated with vascular dementia [32]. Our finding of a 2-fold increase in the risk of developing AD among women carrying rs4986938 is consistent with prior studies [30,31], but we did not see strong associations with rs1256065 or rs1256043, as seen previously [29,33]. We have identified 3 new SNPS of ESR2, rs17766755, rs4365213 and rs12435857, in introns seven (rs17766755) and six (rs4365213 and rs12435857). These SNPs are in high linkage disequilibrium and are associated with a 2-fold increased risk of AD.

Our study points to the role of genetic variants that influence estrogen receptor activity in modifying the risk for AD. Our results support and extend findings from prior studies suggesting that variants in ESR2 modify the risk for AD, both in the general population and in this high-risk group of women with DS. With the exception of rs1255998, all SNPs examined were intronic: rs1255998 is located in exon nine, but does not involve a coding change. The 12 additional SNPs were tested in noncoding (intron) regions and therefore they may not be the critical location of the pathological variants, but rather serve as markers for the critical region. Analysis of additional polymorphisms influencing estrogen biosynthetic pathways and estrogen receptor activity with additional and denser SNP coverage and correlative studies in brain cells will be useful to determine the contribution of estrogen variants to cognitive aging and a risk for AD.

Acknowledgements

Our work was supported by federal grants AG014673 and HD035897 and by funds provided by New York State through its Office of People With Developmental Disabilities.

References

- 1.Yaffe K, Sawaya G, Lieberburg I, Grady D. Estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women: effects on cognitive function and dementia. JAMA. 1998;279:688–695. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.9.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman Y, Bruce AJ, Cheng B, Mattson MP. Estrogens attenuate and corticosterone exacerbates excitotoxicity, oxidative injury, and amyloid beta-peptide toxicity in hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1836–1844. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66051836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luine VN. Estradiol increases choline acetyltransferase activity in specific basal forebrain nuclei and projection areas of female rats. Exp Neurol. 1985;89:484–490. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(85)90108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toran-Allerand CD, Miranda RC, Bentham WD, Sohrabji F, Brown TJ, Hochberg RB, MacLusky NJ. Estrogen receptors colocalize with low-affinity nerve growth factor receptors in cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4668–4672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behl C. Amyloid beta-protein toxicity and oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;290:471–480. doi: 10.1007/s004410050955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe AB, Toran-Allerand CD, Greengard P, Gandy SE. Estrogen regulates metabolism of Alzheimer amyloid beta precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13065–13068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demissie S, Cupples LA, Shearman AM, Gruenthal KM, Peter I, Schmid CH, Karas RH, Housman DE, Mendelsohn ME, Ordovas JM. Estrogen receptor-alpha variants are associated with lipoprotein size distribution and particle levels in women: the Framingham Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;185:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shugrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor -alpha and -beta mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:507–525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<507::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McEwen BS. Invited review: estrogens effects on the brain: multiple sites and molecular mechanisms. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:2785–2801. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuiper GG, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Gustafsson JA. The estrogen receptor beta subtype: a novel mediator of estrogen action in neuroendocrine systems. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1998;19:253–286. doi: 10.1006/frne.1998.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Scrimo PJ, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha (ER-alpha) and beta (ER-beta) mRNA in the rat pituitary, gonad, and reproductive tract. Steroids. 1998;63:498–504. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creutz LM, Kritzer MF. Mesostriatal and mesolimbic projections of midbrain neurons immunoreactive for estrogen receptor beta or androgen receptors in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2004;476:348–362. doi: 10.1002/cne.20229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu F, Day M, Muniz LC, Bitran D, Arias R, Revilla-Sanchez R, Grauer S, Zhang G, Kelley C, Pulito V, Sung A, Mervis RF, Navarra R, Hirst WD, Reinhart PH, Marquis KL, Moss SJ, Pangalos MN, Brandon NJ. Activation of estrogen receptor-beta regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity and improves memory. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:334–343. doi: 10.1038/nn2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishunina TA, Swaab DF. Increased expression of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savaskan E, Olivieri G, Meier F, Ravid R, Muller-Spahn F. Hippocampal estrogen beta-receptor immunoreactivity is increased in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2001;908:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02610-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandi ML, Becherini L, Gennari L, Racchi M, Bianchetti A, Nacmias B, Sorbi S, Mecocci P, Senin U, Govoni S. Association of the estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms with sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265:335–338. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji Y, Urakami K, Wada-Isoe K, Adachi Y, Nakashima K. Estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms in patients with Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia and alcohol-associated dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11:119–122. doi: 10.1159/000017224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattila KM, Axelman K, Rinne JO, Blomberg M, Lehtimaki T, Laippala P, Roytta M, Viitanen M, Wahlund L, Winblad B, Lannfelt L. Interaction between estrogen receptor 1 and the epsilon4 allele of apolipoprotein E increases the risk of familial Alzheimer's disease in women. Neurosci Lett. 2000;282:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yaffe K, Lui LY, Grady D, Stone K, Morin P. Estrogen receptor 1 polymorphisms and risk of cognitive impairment in older women. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:677–682. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corbo RM, Gambina G, Ruggeri M, Scacchi R. Association of estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) PvuII and XbaI polymorphisms with sporadic Alzheimer's disease and their effect on apolipoprotein E concentrations. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22:67–72. doi: 10.1159/000093315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porrello E, Monti MC, Sinforiani E, Cairati M, Guaita A, Montomoli C, Govoni S, Racchi M. Estrogen receptor alpha and APOE epsilon4 polymorphisms interact to increase risk for sporadic AD in Italian females. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:639–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schupf N, Lee JH, Wei M, Pang D, Chace C, Cheng R, Zigman WB, Tycko B, Silverman W. Estrogen receptor-alpha variants increase risk of Alzheimer's disease in women with Down syndrome. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25:476–482. doi: 10.1159/000126495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iivonen S, Corder E, Lehtovirta M, Helisalmi S, Mannermaa A, Vepsalainen S, Hanninen T, Soininen H, Hiltunen M. Polymorphisms in the CYP19 gene confer increased risk for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;62:1170–1176. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118208.16939.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Combarros O, Riancho JA, Infante J, Sanudo C, Llorca J, Zarrabeitia MT, Berciano J. Interaction between CYP19 aromatase and butyrylcholinesterase genes increases Alzheimer's disease risk. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;20:153–157. doi: 10.1159/000087065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corbo RM, Gambina G, Ulizzi L, Moretto G, Scacchi R. Genetic variation of CYP19 (aromatase) gene influences age at onset of Alzheimer's disease in women. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27:513–518. doi: 10.1159/000221832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler HT, Warden DR, Hogervorst E, Ragoussis J, Smith AD, Lehmann DJ. Association of the aromatase gene with Alzheimer's disease in women. Neurosci Lett. 2010;468:202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang PN, Liu HC, Liu TY, Chu A, Hong CJ, Lin KN, Chi CW. Estrogen-metabolizing gene COMT polymorphism synergistic APOE epsilon4 allele increases the risk of Alzheimer disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19:120–125. doi: 10.1159/000082663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forsell C, Enmark E, Axelman K, Blomberg M, Wahlund LO, Gustafsson JA, Lannfelt L. Investigations of a CA repeat in the oestrogen receptor beta gene in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:802–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pirskanen M, Hiltunen M, Mannermaa A, Helisalmi S, Lehtovirta M, Hanninen T, Soininen H. Estrogen receptor beta gene variants are associated with increased risk of Alzheimer's disease in women. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:1000–1006. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambert JC, Harris JM, Mann D, Lemmon H, Coates J, Cumming A, St-Clair D, Lendon C. Are the estrogen receptors involved in Alzheimer's disease? Neurosci Lett. 2001;306:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luckhaus C, Spiegler C, Ibach B, Fischer P, Wichart I, Sterba N, Gatterer G, Rainer M, Jungwirth S, Huber K, Tragl KH, Grunblatt E, Riederer P, Sand PG. Estrogen receptor beta gene (ESRbeta) 3′-UTR variants in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:322–323. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213861.12484.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dresner-Pollak R, Kinnar T, Friedlander Y, Sharon N, Rosenmann H, Pollak A. Estrogen receptor beta gene variant is associated with vascular dementia in elderly women. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13:339–342. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2008.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yaffe K. Estrogens, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and dementia: what is the evidence? Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;949:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb04024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schupf N, Zigman W, Kapell D, Lee JH, Kline J, Levin B. Early menopause in women with Down's syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1997;41:264–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai F, Williams RS. A prospective study of Alzheimer disease in Down syndrome. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:849–853. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520440031017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zigman WB, Schupf N, Sersen E, Silverman W. Prevalence of dementia in adults with and without Down syndrome. Am J Ment Retard. 1996;100:403–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mann DM. The pathological association between Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 1988;43:99–136. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(88)90041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teller JK, Russo C, DeBusk LM, Angelini G, Zaccheo D, Dagna-Bricarelli F, Scartezzini P, Bertolini S, Mann DM, Tabaton M, Gambetti P. Presence of soluble amyloid beta-peptide precedes amyloid plaque formation in Down's syndrome. Nat Med. 1996;2:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rumble B, Retallack R, Hilbich C, Simms G, Multhaup G, Martins R, Hockey A, Montgomery P, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. Amyloid A4 protein and its precursor in Down's syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1446–1452. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906013202203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schupf N, Pang D, Patel BN, Silverman W, Schubert R, Lai F, Kline JK, Stern Y, Ferin M, Tycko B, Mayeux R. Onset of dementia is associated with age at menopause in women with Down's syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:433–438. doi: 10.1002/ana.10677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schupf N, Winsten S, Patel B, Pang D, Ferin M, Zigman WB, Silverman W, Mayeux R. Bioavailable estradiol and age at onset of Alzheimer's disease in postmenopausal women with Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2006;406:298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel BN, Pang D, Stern Y, Silverman W, Kline JK, Mayeux R, Schupf N. Obesity enhances verbal memory in postmenopausal women with Down syndrome. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aylward EH, Burt DB, Thorpe LU, Lai F, Dalton A. Diagnosis of dementia in individuals with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1997;41:152–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geng L, Yao Z, Yang H, Luo J, Han L, Lu Q. Association of CA repeat polymorphism in estrogen receptor beta gene with postmenopausal osteoporosis in Chinese. J Genet Genomics. 2007;34:868–876. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(07)60098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ichikawa S, Koller DL, Peacock M, Johnson ML, Lai D, Hui SL, Johnston CC, Foroud TM, Econs MJ. Polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) gene are associated with bone mineral density in Caucasian men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5921–5927. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kung AW, Lai BM, Ng MY, Chan V, Sham PC. T-1213C polymorphism of estrogen receptor beta is associated with low bone mineral density and osteoporotic fractures. Bone. 2006;39:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Massart F, Marini F, Bianchi G, Minisola S, Luisetto G, Pirazzoli A, Salvi S, Micheli D, Masi L, Brandi ML. Age-specific effects of estrogen receptors' polymorphisms on the bone traits in healthy fertile women: the BONTURNO study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rivadeneira F, van Meurs JB, Kant J, Zillikens MC, Stolk L, Beck TJ, Arp P, Schuit SC, Hofman A, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, van Duijn CM, van Leeuwen JP, Pols HA, Uitterlinden AG. Estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) polymorphisms in interaction with estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF1) variants influence the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1443–1456. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cox DG, Bretsky P, Kraft P, Pharoah P, Albanes D, Altshuler D, Amiano P, Berglund G, Boeing H, Buring J, Burtt N, Calle EE, Canzian F, Chanock S, Clavel-Chapelon F, Colditz GA, Feigelson HS, Haiman CA, Hankinson SE, Hirschhorn J, Henderson BE, Hoover R, Hunter DJ, Kaaks R, Kolonel L, LeMarchand L, Lund E, Palli D, Peeters PH, Pike MC, Riboli E, Stram DO, Thun M, Tjonneland A, Travis RC, Trichopoulos D, Yeager M. Haplotypes of the estrogen receptor beta gene and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:387–392. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gallicchio L, Berndt SI, McSorley MA, Newschaffer CJ, Thuita LW, Argani P, Hoffman SC, Helzlsouer KJ. Polymorphisms in estrogen-metabolizing and estrogen receptor genes and the risk of developing breast cancer among a cohort of women with benign breast disease. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsezou A, Tzetis M, Gennatas C, Giannatou E, Pampanos A, Malamis G, Kanavakis E, Kitsiou S. Association of repeat polymorphisms in the estrogen receptors alpha, beta (ESR1, ESR2) and androgen receptor (AR) genes with the occurrence of breast cancer. Breast. 2008;17:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Treeck O, Elemenler E, Kriener C, Horn F, Springwald A, Hartmann A, Ortmann O. Polymorphisms in the promoter region of ESR2 gene and breast cancer susceptibility. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;114:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gold B, Kalush F, Bergeron J, Scott K, Mitra N, Wilson K, Ellis N, Huang H, Chen M, Lippert R, Halldorsson BV, Woodworth B, White T, Clark AG, Parl FF, Broder S, Dean M, Offit K. Estrogen receptor genotypes and haplotypes associated with breast cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8891–8900. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maguire P, Margolin S, Skoglund J, Sun XF, Gustafsson JA, Borresen-Dale AL, Lindblom A. Estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) polymorphisms in familial and sporadic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;94:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-7697-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Surekha D, Sailaja K, Rao DN, Raghunadharao D, Vishnupriya S. Oestrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) polymorphism and its influence on breast cancer risk. J Genet. 2009;88:261–266. doi: 10.1007/s12041-009-0038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bandera CA, Takahashi H, Behbakht K, Liu PC, LiVolsi VA, Benjamin I, Morgan MA, King SA, Rubin SC, Boyd J. Deletion mapping of two potential chromosome 14 tumor suppressor gene loci in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:513–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lurie G, Wilkens LR, Thompson PJ, McDuffie KE, Carney ME, Terada KY, Goodman MT. Genetic polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) gene and the risk of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9216-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim JJ, Choi YM, Choung SH, Yoon SH, Lee GH, Moon SY. Estrogen receptor beta gene +1730 G/A polymorphism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:1942–1947. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rissman EF, Heck AL, Leonard JE, Shupnik MA, Gustafsson JA. Disruption of estrogen receptor beta gene impairs spatial learning in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3996–4001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012032699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fitzpatrick JL, Mize AL, Wade CB, Harris JA, Shapiro RA, Dorsa DM. Estrogen-mediated neuroprotection against beta-amyloid toxicity requires expression of estrogen receptor alpha or beta and activation of the MAPK pathway. J Neurochem. 2002;82:674–682. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Sen S, Cauley J, Ferrell R, Penninx B, Harris T, Li R, Cummings SR. Estrogen receptor genotype and risk of cognitive impairment in elders: findings from the Health ABC study. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:607–614. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]