Abstract

Polyclonal and monoclonal antisera raised to tetanus toxoid-conjugated polysaccharide of lipopolysaccharide (lps) and purified lps of Pseudomonas pseudomallei that reacted with a collection of 41 strains of this bacterium from 23 patients are described. The common antigen recognized by these sera was within the polysaccharide component of the lps of the cells. The sera were specific for P pseudomallei in that none of 37 strains of other bacteria, including 20 Gram-negative and three Gram-positive species, were recognized, although cross-reaction occurred using the anticonjugate serum with some strains of Pseudomonas cepacia serotype A, a closely related bacterium. Passive protection studies using a diabetic rat model of P pseudomallei infection showed that partially purified rabbit polyclonal and mouse monoclonal antisera were protective when the median lethal dose was raised by four to five orders of magnitude. The wide distribution of the polysaccharide antigen among isolates of P pseudomallei used in this study and the protective role of antibody to the conjugated polysaccharide antigen suggest potential as a vaccine.

Keywords: Lipopolysaccharide, Melioidosis, Pseudomonas pseudomallei, Vaccine

RÉSUMÉ :

Les antiséra polyclonaux et monoclonaux élaborés contre le polysaccharide tétanique toxoïdo-conjugué du lipopolysaccharide (lps) et du lps purifié de Pseudomonas pseudomallei, qui ont réagi avec une série de 41 souches de cette bactérie provenant de 23 patients, sont décrits ici. L’antigène commun reconnu par ces sera se trouvait dans la composante polysaccharide du lps des cellules. Les seras étaient spécifiques au P pseudomallei en ce sens qu’aucune des 37 souches des autres bactéries, y compris 20 espèces gram-négatives et 3 espèces gram-positives n’a été reconnue, bien qu’une réaction croisée se soit produite lors de l’emploi de sérum anticonjugué avec des souches de Pseudomonas cepacia de sérotype A, une bactérie très apparentée. Des études de protection passive à l’aide d’un modèle d’infection à P pseudomallei chez le rat diabétique ont révélé que les antiséra partiellement purifiés polyclonaux de lapins et monoclonaux de souris conféraient une protection lorsque la dose létale médiane était multipliée par 4 ou 5. La grande distribution de l’antigène du polysaccharide parmi les isolats de P pseudomallei utilisés dans cette étude et le rôle protecteur de l’anticorps à l’endroit de l’antigène du polysaccharide donnent à penser qu’il pourrait jouer un rôle en vaccination.

Pseudomonas pseudomallei is the causative organism of melioidosis, a disease of both humans and animals. In recent years the incidence of melioidosis, which is most commonly found in Southeast Asia and northern Australia, has been found to be higher than once considered (1,2). The fulminating septicemic form is probably only the most obvious manifestation of a disease spectrum varying from this extreme to mild or subclinical forms of the disease.

Investigations in Thailand have shown that clinically apparent severe melioidosis is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in that country and is more widespread than appreciated until recently. It seems likely that a majority of patients is asymptomatic after infection, and some may harbour the organism for many years. Clinically apparent infection may present as localized acute suppurative or chronic granulomatous illness or septicemic disease from either a demonstrable or a nondemonstrable primary site. Pneumonic manifestations are common in severe disease. Severe disease is worse with certain risk factors, especially diabetes mellitus, but other underlying diseases have also been detected (1,2). Recently neurological melioidosis has been described probably due to exotoxin-mediated pathology in that there was absence of direct infection of the central nervous system (3).

The pattern of antimicrobial susceptibility of P pseudomallei has been well defined. Chloramphenicol, doxycycline, tetracycline, kanamycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole have been used for treatment. More recently ceftazidime, piperacillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or imipenem-cilastatin have been used. In vitro susceptibility studies show that imipenem is the most active of available drugs, with piperacillin, doxycycline, amoxycillin/clavulanic acid, cefixime, cefetamet, azlocillin and ceftazidime also being very active.

Untreated disseminated melioidosis has a mortality rate of close to 90%. Antimicrobial therapy reduces mortality and improves outcome but therapeutic failure is still common (2,4).

No effective method of prevention of melioidosis exists. We believe it is reasonable to conclude that blood borne antibody would be potentially helpful because of the septicemic nature of severe disease. We therefore undertook to develop antisera to an antigenic preparation of P pseudomallei that would react widely with strains arising from different patients and that would prevent or reduce the severity of disease in infected animals. We report here the results of our studies to provide such a preventive approach to melioidosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions:

P pseudomallei strains 199a, 199b, 230, 231a, 231a/ml, 244a, 264b, 293a, 293a/m4, 303a, 303d, 303e, 304b, 304f, 305a, 305a/ml, 305d, 307a, 307d, 307e, 316a, 316c, 319a, 319c, 365a, 365b, 365c, 375a, 390a, 390d, 392a, 392f, 402a, 402g, 405a, 415a, 415b, 415c, 415d, 420a, 438a, 438c, 443a and 443c were patient isolates from Ubon, Thailand; NCTC8708 was obtained from the United Kingdom National Collection of Type Cultures. Isolates from different patients were given different numbers, and those from different times in the course of treatment of the same patient were given a letter in addition to the number. Strains with the suffix ‘/m1’ or ‘m4’ were laboratory selected antibiotic-resistant mutants. All were provided by one of the authors (D Dance). All the other strains (listed in Table 2) except for isolates of Pseudomonas cepacia, were from the collection of LE Bryan at Foothills Hospital and the University of Calgary. P cepacia strains K19-2, K30-6, K33-1, K41-6, K43-3, K45-1, K53-2, K56-2, K61-3, HI729-2, Pc224c, Pc710M (all serotype A, [5]). Pc99bb (serotype B), 5530pk (serotype C), Pc52Ti (serotype D), K63-2 (serotype E) and 12544 (nontypeable) were from the strain collection of D Woods, University of Calgary. All cultures were grown at 37°C in air using either trypticase soya agar (Difco, Michigan) or brain heart infusion broth (Difco), except Haemophilus influenzae and Haemophilus parainfluenzae, which were grown with 5% carbon dioxide on chocolate agar (Difco).

TABLE 2.

Examination of various bacteria by ELISA

| Bacteria | Strain | A405reading* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antipolysaccharide serum | Monoclonal serum | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 503, 503-18 (rough) | 0 | 0 |

| P aeruginosa | PAO1 | 0 | ND |

| Pseudomonas putida | FH | 0 | ND |

| Pseudomonas cepacia | Serotype A K19-2 | 0.16 | 0 |

| P cepacia | Serotype A K30-6 | 0.235 | 0 |

| P cepacia | Serotype A K33-1 | 0.28 | 0 |

| P cepacia | Serotypes A K41-6, A K43-3, A K45-1, A K53-2 | 0 | 0 |

| P cepacia | Serotype A K56-2 | 0.135 | 0 |

| P cepacia | Serotype A K61-3 | 0.22 | 0 |

| P cepacia | Serotype A H1729-2 | 0.14 | 0 |

| P cepacia | Serotype A Pc710M | 0.06 | 0 |

| P cepacia | Serotype A Pc224c | 0.48 | 0 |

| P cepacia | Serotypes B Pc99bb, C 5530pk, D Pc52Ti, E K63-2, nontypeable | 0 | 0 |

| Xanthomonas maltophilia | FH | 0 | 0 |

| Escherichia coli | HB101, O157, 39-13, SA 1306, DH5 | 0 | 0 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | FH | 0 | 0 |

| Pasteurella multocida, Salmonella typhimurium | FH | 0 | 0 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes, Escherichia cloacae, Haemophilus parainfluenzae | FH | 0 | ND |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | FH | 0 | 0.1 |

| Proteus mirabilis, Proteus vulgaris | FH | 0 | 0 |

| Providencia stuartii | FH | 0.05 | ND |

| Serratia marcescens, Yersinia enterocolitica, Flavobacterium odoratum, Aeromonas hydrophilia | FH | 0 | 0 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes, Enterococcus faecalis | FH | 0 | 0 |

| Bacillus subtilus, Staphylococcus aureus | FH | 0 | ND |

| Pseudomonas pseudomallei | 304f | 0.6 | ND |

| P pseudomallei | 307a | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| P pseudomallei | 415a | 1 | ND |

| P pseudomallei | 304b, 305a, 415b | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| P pseudomallei | 303a, 307d, 307e, 316c, 319a, 415c, 415d | 0.8 | ND |

| P pseudomallei | 230 | 1.2 | 0.25 |

| P pseudomallei | 199b, 231a, 244a, 293a, 305a/M, 305d, 319c, 390a, 420a, 438c | 1.2 | ND |

| P pseudomallei | 264b | 1.3 | 0.25 |

| P pseudomallei | 316a, 365a, 392f | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| P pseudomallei | 392a | 1 | 0.6 |

| P pseudomallei | 231 a/M, 365c, 402a, 402g, 405a | 1.1 | ND |

| P pseudomallei | 438a | 1.3 | 0.6 |

| P pseudomallei | 390d, 443a, 443c | 1.3 | ND |

| P pseudomallei | NCTC 8708 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| P pseudomallei | 293a/M | 1.5 | 0.4 |

| P pseudomallei polysaccharide | 304b | 2.4 | >2.5 |

| Tetanus toxoid | >2.5 | 0 | |

| Toxoid polysaccharide conjugate | >2.5 | ND | |

| P pseudomallei LPS | 304b | >2.5 | >2.5 |

| P aeruginosa LPS | PAO 503 (type B) | <0.1 | 0 |

| P aeruginosa LPS | Serotype E | <0.1 | 0 |

Control normal rabbit serum; all examinations were the average of three or more experiments. 0 indicates ≤0.05. ELISA Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FH Foothills Hospital strain collection; LPS Lipopolysaccharide; ND Not done

Purification of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and polysaccharide (PS):

lps from late logarithmic growth phase P pseudomallei was extracted by the phenol water method of Westphal and Jann (6) to favour preparation of long chain lps. Nucleic acids were removed by selective precipitation with cetyl-ammonium bromide (‘cetavlon’). The nucleic acid-free lps in solution was precipitated in cold ethanol, recovered by low speed centrifugation, dissolved in water, dialyzed and lyophilized. ps was obtained from lps by mild acid hydrolysis in 1% acetic acid held at 100°C for 4 h in a sealed glass ampoule. Lipid A was removed by centrifugation for 15 mins at 12,720 g. The remaining material was extracted three times with chloroform/methanol (2/1 V/V). The aqueous phase was extensively dialyzed against distilled water and lyophilized. Some batches of lps were also prepared using the Darveau and Hancock method (7) to examine reactivity of lps extracted by two methods.

Conjugation of PS to tetanus toxoid:

The method was adapted from described methods (8–10). A solution of ps (5 mg/mL) equilibrated at 4°C was rapidly brought to pH 10.5 with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide, and 100 mg/mL cyanogen bromide was added to a final concentration of 0.4 mg/mL ps. The pH was maintained at 10.5 for 6 mins, after which the pH was brought to 8.5 with 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate. Adipic acid dihydrazide (20 mg) was added next and the mixture incubated at 4°C for 16 h. The mixture was dialyzed against 500 volumes of water for 48 h, after which the pH was adjusted with hydrochloric acid to 4.7. Tetanus toxoid (10 mg) (Institut Armand Frappier) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (100 mg) were added and the reaction mixture stirred for 4 h at 25°C. This conjugation mixture was thereafter dialyzed against 500 volumes of phosphate buffered saline (pbs) (pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C and lyophilized. The conjugated ps-tetanus toxoid was purified from lps, ps and tetanus toxoid by Sephacryl S-500 column chromatograph (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology). A volume of 0.55 mL conjugate mixture was loaded on a Sephacryl S-500 column with 28 mL bed volume at a flow rate of 0.5 mL 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0)/min and 0.8 mL fractions collected. From the elution profile determined by protein assay (BCA Micro-protein Assay, Illinois) and carbohydrate test (11), a peak containing both protein and carbohydrate was collected. The pooled fractions were lyophilized and reconstituted with 1 mL sterile water for injection.

Production of anticonjugate antibodies:

A New Zealand White female rabbit was immunized by intravenous injection of 1 mL of 50 μg/mL conjugate solution on days 1, 10 and 17. Blood was taken on day 24 and the serum was collected and tested using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (elisa) with lps, ps and tetanus toxoid as antigens. The rabbit was terminally bled on day 32, serum was collected and frozen in aliquots at −70°C. A 1.5°C maximal temperature response occurred with the initial injection, suggesting, despite purification, some minor lps contamination of this preparation.

ELISA procedures:

Round bottomed microtitre plates (Dynatech Laboratories Inc, Virginia) were coated with 5 μg bovine serum albumin, Pseudomonas aeruginosa 503 lps, P aeruginosa serotype A and serotype E lps, P pseudomallei lps, P pseudomallei ps, ps-tetanus toxoid conjugate or tetanus toxoid in 100 μL of 0.05 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.6. Plates were incubated at 4°C overnight or 37°C for 1 h. The plates were washed three times in pbs containing 0.05% Tween-20. A blocking step was performed with 1% skim milk in pbs. One hundred microlitres of each of the serum dilutions were prepared in pbs with 1% skim milk and incubated in appropriate wells for 1 h at 37°C. After washing, 100 μL of horseradish peroxidase conjugate antirabbit immunoglobulin (Ig) G was added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After washing, 100 μL per well of substrate ( 2-2′-azino-di[3-ethyl-berrzthiazoline sulphonate]) (KPL Inc, Maryland) was added and colour allowed to develop for at least 10 mins before the absorbance at 405 nm was measured using a Bio-Tek Instrument Inc EIA autoreader model EL 310 (Mandell Scientific Co Ltd).

Specificity of the antipolysaccharide reaction:

Reaction of the antibody with a range of bacteria and lps, ps and tetanus toxoid preparations was determined by elisa and immunoblot assays. Bacterial cells were grown overnight either in brain heart infusion broth or tryptic soya agar. The cells were washed and adjusted to 0.6 optical density 600 nm in pbs. One millilitre of cell suspension was collected in a microfuge tube. After the pellet was resuspended in 50 μL pbs, the suspension was boiled for 10 mins at 100°C, and 25 μg of proteinase K in a 10 μL volume was added and incubated for 1 h at 60°C to ensure no residual contaminating P pseudomallei protein remained. The final volume was made up to 500 μL with 0.5 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). One hundred microlitres of each antigen preparation was added per well of the elisa plate and incubated at 4°C overnight. After washing and blocking as described above, 100 μL of a 1:1000 dilution of antiserum was added per well and plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Absorbance readings at 405 nm were determined after addition of peroxidase-anti-IgG conjugate and substrate as described above. The control was an identical dilution of normal rabbit serum collected from the same rabbit before immunization.

Immunoblots were performed in the following manner. Bacterial cells were adjusted to 0.6 optical density 600 nm in saline and pelleted in microfuge tubes. The cells were washed once in saline and resuspended in 50 μL sample buffer (4% sodium dodecyl sulphate [sds], 10% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and trace of bromophenol blue in Tris buffer, pH 6.7). The samples were boiled for 10 mins at 100°C followed by addition of proteinase K (25 μg dissolved in 10 μL sample buffer) and dnaase (10 μg dissolved in 10 μL sample buffer) to each sample. The samples were incubated for 60 mins at 60°C. Tetanus toxoid (40 μg protein per well), lps and ps (40 μg/well) and the whole cell lps preparations were loaded onto a 15% sds-urea polyacrylamide gel, and electrophoresis was carried out (12). Gels were thereafter blotted on Immobilon transfer membrane ‘Millipore PVDF’ (Millipore Canada Ltd). Immunoassay was performed by initial blocking of membranes using 1% skim milk in Tris buffered saline (pH 7.4), followed by washing with Tris buffered saline. The antitetanus toxoid/ps antibody was used at a 1:1000 dilution, incubated for 1 h at 37°C, washed with Tris buffered saline, treated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated antirabbit IgG (ICN ImmunoBiologicals, Illinois) for 1 h at 37°C and the substrate 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Bio Rad) added to allow colour development.

Absorption of the antitetanus toxoid/PS antiserum:

Purified lps (1 μg/μL ) from P pseudomallei 304b was digested with proteinase K at a concentration of 2 μg/μg of lps. One microgram of the digested lps was added to 20 μL of 1:2 and 1:20 diluted serum and incubated overnight at 4°C. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation using a microfuge at 12,718 g for 15 mins. Thereafter the elisa procedure was used to determine the reduction in titre using sodium hydroxide-lysed whole cell antigen preparations from P pseudomallei strain 304b and a final dilution of ps antiserum of 1:2000.

Monoclonal antibody production:

Polysaccharide antigens were from sds page gels in an electroelutor (Tyler Research Instruments). The antigens were extensively dialyzed against distilled water to remove sds and subsequently lyophilized to concentrate the preparation. A balb/c mouse (Simonsen Labs Inc, California) was immunized by initial intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg of electroeluted antigen preparation in a 50 μL volume and 50 μg of N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanyl-D-isoglutamine (Sigma). The same quantity of antigen was injected intravenously once a week for three more weeks.

Subsequently the mouse was sacrificed, the spleen removed and fusion performed using the NS-1 myeloma cell line (12). Monoclonal antibody mca PS-Pp-W was identified by reaction with partially purified lps of P pseudomallei on Western blot as well as by elisa. The specificity of the monoclonal antibody for other bacteria was determined by reaction with a variety of other bacteria.

Agglutination reaction:

Bacterial cells (50 μL of 2.0 A600 suspension /mL in pbs) were suspended on a glass slide and an equal volume of undiluted serum was mixed with the cells. A positive agglutination result could be visualized within 1 min. A control was performed with normal rabbit serum.

Bactericidal activity of the immune serum:

The method was adapted from previously described methods (13,14). Anti-ps rabbit serum used in this assay was stored at −70°C in aliquots, and the serum was never refrozen. Bacteria were grown overnight or until mid-logarithmic growth phase in brain heart infusion broth, then washed and resuspended in saline to a concentration of 107 colony-forming units (cfu)/mL. The saline suspension was diluted 10-fold in Hank’s buffered saline solution (Gibco) containing 0.1% (W/V) gelatin (Sigma). At time zero, the bacterial suspension (106 cfu/mL) was diluted 10-fold by adding it to a tube containing Hank’s buffered saline solution with 0.1% gelatin and 10% (V/V) anti-ps rabbit serum and 10% (V/V) guinea pig complement (ICN ImmunoBiologicals). Control tubes contained the same reaction mixture, but with normal rabbit serum and without serum. Tubes were incubated at 37°C, and at various intervals samples were taken, serially 10-fold diluted in saline, and 0.1 mL aliquots were plated in duplicate onto trypticase soya agar plates for viable counts.

Animal protection studies:

Three separate experiments were performed using an animal model of septicemic P pseudomallei infection in diabetic rats (15). Forty-five male Sprague-Dawley rats with an average weight of 50 g were used for each experiment. Animals were given intraperitoneal injections of either pbs or streptozotocin (Sigma, 80 mg/kg body weight for each of two consecutive days) to induce diabetes. Urine glucose levels were monitored (Diastix, Miles Canada, Inc) to assess the onset of diabetes. Diabetic animals were given 10 mU/g body weight NPH insulin (Connaught Novo) intraperitoneally when urine glucose levels reached 160 mmol/L. Three days post insulin injection, groups of 15 animals (five nondiabetic-nonimmunized, five diabetic-nonimmunized and five diabetic-immunized) were inoculated intraperitoneally with 104, 105 or 106 P pseudomallei strain 316c organisms. Passive immunization was achieved by intraperitoneal injection of sterile IgG (anti-ps serum) or IgM (monoclonal antibody) partially purified by ammonium sulphate precipitation (1.5 mg in 0.1 mL pbs) at the time of inoculation (16). Nonimmunized animals received intraperitoneal injections of 0.1 mL pbs. The experimental end-point was death and median lethal dose (LD50) values were determined using the method of Reed and Muench (17).

RESULTS

LPS patterns of P pseudomallei strains:

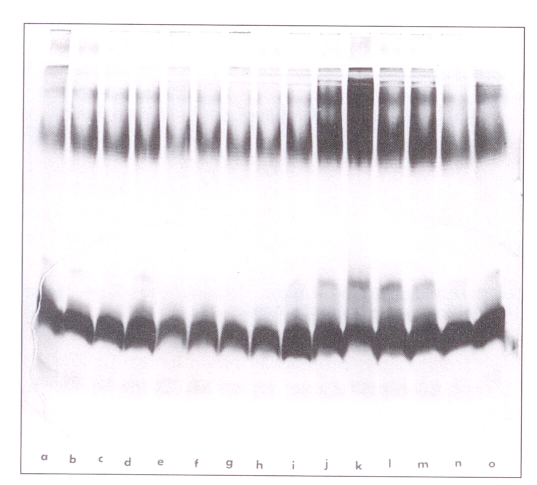

Figure 1 shows the lps staining patterns of 12 strains of proteinase K-digested whole cells of P pseudomallei using the method of Hitchcock and Brown (18). This set consists of strains isolated from six different patients (365, 392, 316, 305, 415 and 443) with multiple isolations from each patient taken early and late in the course of antimicrobial therapy (signified by the lower case letters) (Figure 1). The pattern in all cases was that of a smooth lps, with most higher molecular weight bands clustered in a group in the upper gel consistent with long chain lps. The results of these gels are also consistent with a core and lipid A region to the lps.

Figure 1.

Lipopolysaccharide staining (28) patterns of 12 strains of proteinase K-digested whole cells of Pseudomonas pseudomallei. Strains in the lanes are: a,b: 365a; c: 365c; d: 392a; e,f: 392f; g, h: 316a; i: 316c; j: 305a; k: 305d; l: 415a; m: 415c; n: 443a; o: 443c

Preparation of P pseudomallei PS conjugated to tetanus toxoid and antiserum:

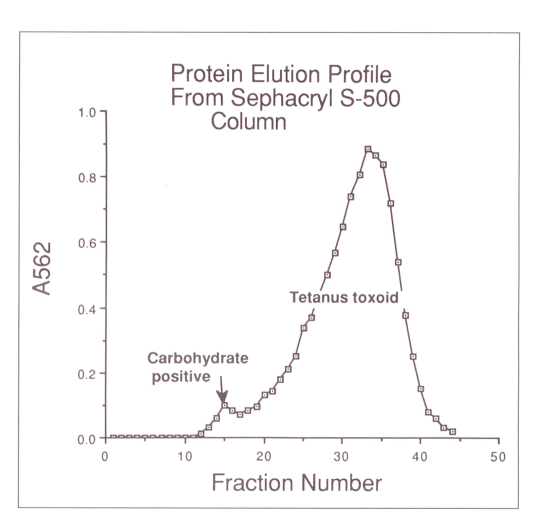

lps was purified from P pseudomallei strain 304b, the ps removed following acid hydrolysis and the ps conjugated to tetanus toxoid as described above. Figure 2 shows the elution profile from a Sephacryl S-500 column of chromatographed material previously subjected to the conjugation procedure as described. A fraction representing larger molecular weight material in a small protein peak immediately preceding the main protein peak of tetanus toxoid and which contained carbohydrate (fractions 13 to 17) was selected for injection into the rabbit. No other ps was detected, indicating that all ps was conjugated due to the gross excess of tetanus toxoid. The serum obtained after three injections (32 days after the initial injection) was termed anti-ps serum and used for all subsequent assays and tests other than those using monoclonal antibody.

Figure 2.

Elution profile from a Sephacryl S-500 column of carbohydrate reactive material from purified and hydrolyzed lipopolysaccharide conjugated to tetanus toxoid. A562 Reading in protein assay

Specificity of anti-PS serum:

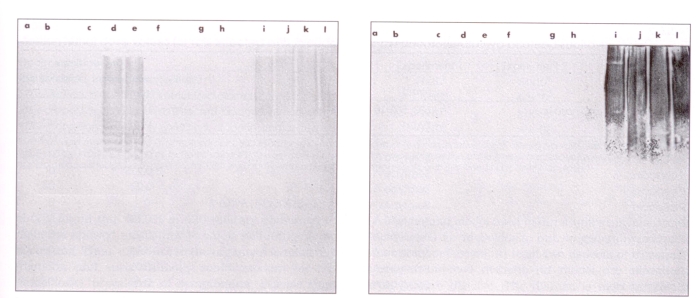

Anti-ps serum at two different dilutions was absorbed with proteinase K-treated lps of P pseudomallei 304b, as described above, to confirm that specificity was not directed to any protein impurity in the antigen preparation. Reactivity with 304b antigen was then determined relative to untreated serum and after absorption with proteinase K-treated lps. A control containing only proteinase K was used in the event this treatment in itself lowered the titre through proteolysis of antibody. Results of absorption studies (Table 1) showed a dose response in that a substantially greater reduction in elisa activity resulted after lps absorption of the more dilute than of the less dilute antiserum preparation. The anti-ps serum reacted with a diffuse region in the higher molecular band region of either lps extracted from P pseudomallei or of proteinase K-digested whole cells on immunoblots, also consistent with a reaction to lps (Figure 3, left). No immunoblot reaction was detected in the region of lps gels where lipid A was expected to migrate. Further, a monoclonal antibody reacting with proteinase K-treated whole cells and lps of strain 304b gave a very similar blot reaction with P pseudomallei strains (Figure 3, right).

TABLE 1.

Absorption of anti-PS serum with proteinase K-treated Pseudomonas pseudomallei LPS

| Preparation | Dilution* of anti-PS serum | Absorption with: | ELISA result (A405) | Ratio of absorbed A405to control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K-LPS | Proteinase K | ||||

| Control (0.5 dilution) | 0.5* | No | No | 0.99 | NA |

| Proteinase K control | 0.50 | No | Yes | 0.99 | 1 |

| LPS + proteinase K | 0.50 | Yes | Yes | 0.63 | 0.64 |

| Control (0.5 dilution) | 0.05 | No | No | 0.97 | NA |

| Proteinase K control | 0.05 | No | Yes | 0.64 | 0.66 |

| LPS + proteinase K | 0.05 | Yes | Yes | 0.1 | 0.16 or 0.10† |

Dilution for absorption is expressed as a fraction, ie, 1:2=0.5; serum was used at a final dilution of 1:2000 in all assays.

Control for ratio was preparation control 2 or proteinase K control; ELISA Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LPS Lipopolysaccharide; PS Polysaccharide

Figure 3.

Reaction of whole cell lipopolysaccharide of selected bacteria and antipolysaccharide serum (left) or monoclonal antibody (right) as shown by immunoblot reaction. Lanes are: a: Pseudomonas cepacia serotype B; b: Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO503; c: P cepacia serotype C; d: P cepacia serotype A (K1 9-2); e: P cepacia serotype A (K1 9-2); f: P cepacia serotype D; g: Aeromonas hydrophilia; h: Yersinia enterocolitica; i: P pseudomallei 415b; j: P pseudomallei 305a; k: P pseudomallei 304b; l: P pseudomallei 199a

The anti-ps serum gave a strong reaction with tetanus toxoid, tetanus toxoid-ps conjugate, purified preparations of the hydrolyzed ps and lps from P pseudomallei 304b in elisa reactions. No reactivity was found with lps from two serotypes of P aeruginosa (Table 2).

The preceding results argue strongly that the major reaction of the anti-ps serum was with ps components of lps conjugated to tetanus toxoid.

Bacteria recognized by anti-PS serum:

A large series of proteinase K-treated whole cells of bacteria was examined for reactivity with anti-ps serum by the elisa procedure. Results consistently showed that the only bacterial species recognized, with one exception in the group tested, was P pseudomallei (Table 2). The exception was a group of several strains belonging to serotype A of P cepacia, a bacterium known to be closely related to P pseudomallei (19). Other serotypes of P cepacia did not react (Table 2, Figure 3, left). Although only one example of serotypes other than type A is shown in Table 2, several isolates of each were tested. P cepacia serotype A strains consistently reacted by elisa and in immunoblots (Figure 3, left) with the anti-ps serum, but not with a monoclonal antibody (IgM) raised against P pseudomallei lps (Table 2, Figure 3, right). Immunoblot results for the two antisera against whole cell digests of P pseudomallei strains 415b, 305a, 304b and 199a as well as isolates of P cepacia, Aeromonas hydrophilia and Yersinia enterocolitica are shown in Figure 3. Whole cell digests of P aeruginosa serotype A, P aeruginosa 503 and 503–18, H influenzae, H parainfluenzae, Escherichia coli O157, E coli HB 101, Xanthomonas maltophilia, Serratia marcescens, Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella typhimurium were also examined using both anti-ps serum and the monoclonal antibody. The results of both elisa (Table 2) and immunoblot reaction (data not shown) were negative.

Interestingly every strain of P pseudomallei examined reacted with the anti-ps serum by the elisa as well as the immunoblot method (Table 2, Figure 3, left). Many of these strains were also examined with the monoclonal antibody by the elisa and immunoblot reaction and all were positive (Table 2, Figure 3, right). P pseudomallei NCTC 8708, 230, 304b, 392a and 392f, and lps extracted from P pseudomallei 304b were also positive by immunoblot assay using both antisera (data not shown), as well as by elisa (Table 2). In all, strains from 23 different patients reacted positively by elisa as did all of the multiple isolates from the same patient (Table 2).

Animal protection studies:

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats were found to be susceptible to P pseudomallei 316c, a different strain from that used to isolate the lps for antibody. LD50 values for P pseudomallei in streptozotocin-treated rats were markedly reduced compared with control animals (Table 3). In three separate experiments the LD50 was raised to greater than 1×108 organisms by injection of the anti-ps serum and to greater than 1×108 organisms in two experiments by injection of the monoclonal antibody. These studies clearly showed that, under these test conditions, passive administration of anti-ps or monoclonal antibody directed to an lps antigen of strain 304b was protective for another P pseudomallei strain.

TABLE 3.

Median lethal dose values for rats infected with Pseudomonas pseudomallei

| Treatment | Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | Experiment 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS (infected, nondiabetic animals) | >1×108 | >1×108 | >1×108 |

| STZ (infected, diabetic, nonimmunized animals)* | 7.3×103 | 4.3×103 | 1.7×104 |

| STZ + antipolysaccharide serum (infected, diabetic, immunized animals)† | >1×108 | >1×108 | >1×108 |

| STZ + monoclonal antibody (infected, diabetic, immunized animals)‡ | >1×108 | >1×108 | Not done |

Animals were made diabetic by streptozotocin (STZ) injection (80 mg/kg for each of two consecutive days);

Sterile partially purified immunoglobulin (Ig) G (1.5 mg in 0.1 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS)) was administered by intraperitoneal injection at the time of bacterial inoculation;

Sterile partially purified monoclonal IgM (1.5 mg in 0.1 mL PBS) was administered by intraperitoneal injection at the time of bacterial inoculation

Bactericidal and agglutinating activity:

It was not possible to show any bactericidal activity of the anti-ps serum or monoclonal antibody against the homologous strain 304b. Anti-ps serum agglutinated several strains of P pseudomallei but the monoclonal antibody did not.

DISCUSSION

Several important findings emerge from this series of investigations. There was apparently only a single serotype of lps recognized by the anti-ps serum or the monoclonal serum raised against a prototype strain of P pseudomallei. Strains originated from 23 different patients indicating that a single serotype is widespread in this group. There could be several reasons for this. The patients could represent a cluster. There is no evidence to support the view that a single strain spread among the different patients. Strains arose from different individuals and locations at different times with no communality among the patients. Preliminary ribotyping studies also indicate that these strains do not represent a single clone (unpublished data). However, it is possible that a single serotype exists in the Thailand region from which these isolates originated, and that other types exist elsewhere or in lower numbers and were not detected in this series.

Another interpretation is that there is only one serotype of P pseudomallei. Current serological procedures do not discriminate serotypes (2,20). Two serotypes reported earlier (21) apparently reflect smooth and rough lps variation and not two serotypes (unpublished data). The indirect hemagglutination (iha) test apparently recognizes a ps antigen that is likely to be the lps. Using this test, Atthasampunna et al (22) found that 15% of Thais had antibody to P pseudomallei. Embi et al (23) found that 65.7% of 420 military personnel in Malaysia showed antibodies to whole cell antigens by iha testing. Thus, exposure to the organism is relatively frequent, and such antibody could account for the much lower prevalence of symptomatic disease than subclinical infection. Recently Pitt et al (24) provided further evidence to suggest that the lps antigen is highly conserved throughout P pseudomallei and that this antigen is detected by the iha test.

A second finding is that the antigen recognized by the monoclonal serum is also recognized by the anti-ps serum. All of our results are consistent with this being a repeating side chain of the lps structure. Further, this antigen is widely distributed in P pseudomallei strains but is not found in a wide variety of other Gram-negative and some Gram-positive bacteria. The only exception to this is the occurrence of this antigen in most of the serotype A isolates of P cepacia examined. The last observation is highly consistent with the close relationship between these two bacteria by a variety of methods (5). Furthermore, some similarity in structure of lps from these two bacteria in the inner core region was recently reported (25). Monoclonal antibody did not react with P cepacia isolates, suggesting that there is more than one epitope included in the lps structure and recognized by the anti-ps serum. It remains an unlikely possibility that the latter serum recognizes a minor non-lps epitope found in both P cepacia and P pseudomallei, although our results support the view that most activity is to an lps antigen.

A third and very important outcome is that a vaccine directed towards the ps portion of the lps could potentially be important in control of melioidosis. This view is supported by the widespread distribution of the protective epitope or epitopes in P pseudomallei strains, the capability to conjugate the ps to a protein carrier, and evidence for protection in an animal model using both polyclonal and monoclonal sera. Results from iha testing suggest that ps is recognized in natural infections and antibodies are produced against it. It is conceivable that such antibody is a major factor in controlling the frequency and severity of melioidosis. There is no definite evidence to confirm either of these speculations, but current findings are consistent with such an interpretation.

The animal model used in our studies may not be an ideal model for melioidosis, but no generally accepted animal model exists. At least two aspects of the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat model are consistent with human disease. The disease is more severe in compromised patients including those with diabetes, leukemia, other malignancies, chronic renal and liver failure, alcoholism, malnutrition and other similar examples (2). Secondly, severe human disease has a bacteremic component to it, as does the diabetic rat model. In these studies antibody was given simultaneously with the infecting dose of bacteria and was highly protective. Similarly, in actively immunized humans, antibody is expected to present at the time of exposure to the bacterium. Therefore, while not absolutely predictive, our protection studies argue strongly that antibodies to the same epitope or epitopes in humans are likely protective. At this time we do not have any information on the possible mechanism of protection, except that we have been unable to detect bactericidal activity. Clearly the passively supplied antibody could be enhancing phagocytosis. We are pursing more complete mechanistic understanding using human studies where we feel these findings will have more definite relevance.

A potential problem with a vaccine developed from lps is toxicity. We have not examined this aspect of the conjugated antigen in detail. However, past experience indicates that toxicity is expected to be minor. As noted above, we did observe a temperature rise in a rabbit injected with the conjugate. The major problem in eliminating some degree of pyrogenicity would be in purifying the vaccine adequately to ensure that contamination with lps is below biologically significant levels. Toxicity associated with the ps and the carrier tetanus toxoid is expected to be small based on results with other conjugated protein-ps vaccines (10). A major attraction of this putative vaccine antigen is its presence in all strains of P pseudomallei examined to date, an uncommon finding for lps antigens of Gram-negative bacteria. The cross-reaction with P cepacia could be an added advantage because this organism is an opportunistic pathogen. Both organisms have produced disease in cystic fibrosis patients (26,27), and the antigen may be a potential vaccine candidate for that group of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Medical Research Council of Canada (L Bryan), the Canadian Bacterial Diseases Network (L Bryan and D Woods), the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (L Bryan) and the Wellcome-Mahidol University, Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Program, funded by the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain (D Dance and W Chaowagul).

REFERENCES

- 1.Dance DAB. Melioidosis: the tip of the iceberg. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:52–60. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laeelarasamee A, Bovornkitti S. Melioidosis: review and update. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:413–25. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woods ML, Currie BJ, Howard DM, et al. Neurological medioidosis – seven cases from the Northern Territory of Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:163–9. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dance DAB, Wuthiekanum V, Chaowagul W, White NJ. The antimicrobial susceptibility of Pseudomonas pseudomallei. Emergence of resistance in vitro and during treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;24:295–309. doi: 10.1093/jac/24.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKevitt AI, Retzer MD, Woods DE. Development and use of a serotyping scheme for Pseudomonas cepacia. Serodiagn Immunother. 1987;1:177–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westphal O, Jann K. Extraction with phenol-water and further applications of the procedure. In: Whistler RL, editor. Methods in Carbohydrate Chemistry V. Vol. 25. San Diego: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darveau RP, Hancock REW. Procedure for isolation of bacterial lipopolysaccharides from both smooth and rough Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhimurium strains. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:831–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.831-838.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cryz SJ, Furer E, Sadoff JC, Germanier R. Pseudomonas aeruginosa polysaccharide-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine: safety and immunogenicity in humans. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:682–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.4.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cryz SJ, Furer E, Sadoff JC, Germanier R. Pseudomonas aeruginosa immunotype 5 polysaccharide-toxin A conjugate vaccine. Infect Immun. 1986;52:161–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.161-165.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneersen R, Barrers O, Sutton A, Robbins J. Preparation, characterization and immunogenecity of Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide-protein conjugate. J Exp Med. 1980;152:361–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois M, Gillies KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schryvers AS, Wong S, Bryan LE. Antigenic relationships among penicillin-binding proteins 1 from members of the famillies Pasteurellaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:559–64. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.4.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guillermo I, Perez-Perez L, Blaser MJ, Bryner JH. Lipopolysaccharide structures of Campylobacter fetus are related to heat-stable serogroups. Infect Immun. 1986;51:209–12. doi: 10.21236/ada265573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pai CH, DeStephano L. Serum resistance associated with virulence in Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1982;35:601–11. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.2.605-611.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones AL, Hill PJ, Woods DE. The role of insulin in the pathogenesis of Pseudomonas pseudomallei infections. Abstracts of the UA-UC Conference on Infectious Diseases; Kananaskis, Alberta. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cryz SJ, Jr, Furer E, Germanier R. Passive protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in an experimental leukopenic mouse model. Infect Immun. 1983;40:659–64. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.2.659-664.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hitchcock PJ, Brown TM. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–77. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashdown LR, Koehler JM. Production of hemolysin and other extracellular enzymes by clinical isolates of Pseudomonas pseudomallei. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2331–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.10.2331-2334.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leelarasamee A. Diagnostic value of indirect hemagglutination method for melioidosis in Thailand. J Infect Dis Antimicrob Agents (Thailand) 1985;2:213–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodin A, Fournier J. Antigenes precipitants et antigenes agglutinants de Pseudomonas pseudomallei. Ann Insitut Pasteur. 1970;119:211–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atthasampunna P, Noyes HE, Winter PE, et al. Annual progress report of SEATO medical research study on melioidosis. Bangkok: SEATO; 1969. pp. 257–64. 1969; Period of report: 1 April 1969–31 March 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Embi N, Suhaimi A, Mohamed R, Ismail G. Prevalence of antibodies to Pseudomonas pseudomallei exotoxin and whole cell antigens in military personnel in Sabah and Sarawak, Malaysia. Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36:899–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitt TL, Aucken H, Dance DAB. Homogeneity of lipopolysaccharide antigens in Pseudomonas pseudomallei. J Infect. 1992;25:139–46. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(92)93920-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawahara K, Dejsirilert S, Danbara H, Ezaki T. Extraction and characterization of lipopolysaccharide of Pseudomonas pseudomallei. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;96:129–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novoa O, Lezana MA. Epidemiology of pseudomonas in Mexican CF patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1989;(Suppl 4):138. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gladman G, Connor PJ, Williams RF, David TJ. Controlled study of Pseudomonas cepacia and Pseudomonas maltophilia in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:192–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.2.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai CM, Frasch CE. A sensitive silver strain for detecting lipolysaccharides in polysaccharide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]