Abstract

This paper describes the first case of babesiosis diagnosed in Canada. This case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of diseases that may be endemic elsewhere and the importance of a travel history in a patient’s assessment.

Keywords: Babesiosis, Intraerythryocytic, Protozoa

RÉSUMÉ :

Le présent article décrit le premier cas de babésiose diagnostiquée au Canada. Ce cas souligne le besoin pour les cliniciens de connaître les maladies qui peuvent être endémiques dans d’autres pays et l’importance des antécédents de voyage dans l’évaluation des patients.

Babesiosis is an infection caused by a protozoa that parasitizes erythrocytes resulting in a malaria-like syndrome. Although an important disease of cattle, it can cause significant disease in humans. In North America, people have acquired the disease on the islands off the northeast coast of the United States, the northeast mainland, the upper midwest and the west coast. With an increasingly mobile population, diseases such as this are being seen outside of their endemic areas or areas of acquisition. To our knowledge, this is the first case of babesiosis diagnosed in Canada.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 66-year-old male from Connecticut presented to a physician in Jasper, Alberta on September 5, 1996, complaining of a one-week history of fever and chills. He also complained of fatigue, loose stools alternating with constipation, abdominal distension and extensive rigors.

He has a vacation home on Block Island off the coast of Rhode Island where he spent the month of July. He had toured Alaska and had been returning through the Canadian Rockies when he developed his symptoms. He had not travelled outside the United States and Canada in his lifetime.

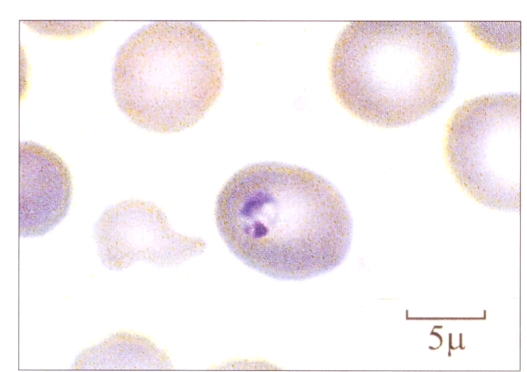

Temperature at presentation was 37.6°C. When examined, there were no abnormalities other than hyperactive bowel sounds. Specifically, there was no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Complete blood cell count showed a white count of 4.9×109/L with a normal differential and hemoglobin of 124 g/L. Platelets were low at 53×109/L. A peripheral blood film was reviewed because of the thrombocytopenia, and intraerythrocytic protozoa were noted in about 1% of erythrocytes. Initially, the hematopathologist felt that this represented Plasmodium falciparum, although the appearance was not entirely typical (Figure 1). However, on reviewing the patient’s history, this diagnosis was felt to be quite unlikely clinically, and the hematopathologist was asked to review the slides again. This time a diagnosis of babesiosis was made. The following day the patient had further smears and blood work done. Urinalysis showed proteins were 0.3 g/L and a trace of leukocytes; the sample was positive for ketones and nitrite. Creatinine levels and liver panel were normal except for a bilirubin of 25 mol/L. Haptoglobin was low at less than 0.06 g/L. Smears confirmed the diagnosis of babesiosis. The patient was treated with seven days of clindamycin 600 mg tid and quinine 650 mg tid. He tolerated this with difficulty due to gastrointestinal adverse effects. However, he completed his course and had been symptom-free for seven months. Acute serum sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia showed a titre of 1/64 for Babesia microti.

Figure 1.

An erythrocyte containing a Babesia microti ring

DISCUSSION

Babesia are the commonest intraerythrocytic parasite of mammals, with about 100 species known (1). These parasites are usually transmitted by ticks of the Ixodes genus. The tick larvae usually acquire the parasites while feeding on animal hosts and commonly transmit babesial sporozoites to humans while in the nymph stage of development. Mature trophozoites reproduce in erythrocytes by asynchronous asexual budding into two or four daughters, which damage the membrane as they exit the erythrocyte. However, the exact mechanism of hemolysis is unknown.

Babesiosis was the first disease recognized to be transmitted by an arthropod vector in 1893 (2). The first human infection with babesia was described in Yugoslavia in 1957 in a farmer who died of fulminant hemolytic anemia (3). The first reported case of babesiosis in the United States was in California in 1966 (4). Since then, several hundred cases in the United States have been recognized, primarily from endemic areas in the northeast such as Nantucket Island, Martha’s Vineyard and Cape Cod, Massachusetts; Block Island, Rhode Island; Shelter Island and Fire Island, New York; and Connecticut. Human infection occurs mainly in the late spring to early fall when tick exposure is greatest. However, most patients do not recall a tick bite because nymphs are only 1 to 2 mm long, tan in color and are easily missed. The European form of babesiosis is due to Babesia bovis or Babesia divergens, which infect cattle, while in the northeast United States babesiosis is caused by B microti, which usually infects rodents. Babesiosis from the west coast of the United States is due to a species closely related to the canine pathogen Babesia gibsoni (5). Clinically, babesia infection in the United States is often asymptomatic to mild, occurs in normal hosts and is rarely fatal in contrast with the European form, where up to 84% of patients are asplenic with a high mortality rate (6).

The compact ring forms of B microti can easily be mistaken for P falciparum malaria (7). The classic tetrad of rings (Maltese cross) described in babesiosis can be difficult to find. Useful discriminating features suggesting babesiosis include the lack of pigment (hemozoin), the presence of a central cytoplasmic vacuole and the absence of intermediate stages such as shizonts or gametocytes (1). Of course the lack of travel to a malaria endemic region, history of travel or residence in a babesia endemic area, or the history of a recent tick bite should raise the clinical suspicion of babesiosis, as it did in this case. A transfusion history is also of importance because asymptomatic individuals infected with babesia may donate blood, unknowingly transmitting the parasite to the recipient.

The incubation period for babesiosis is one to six weeks, which is consistent with the patient leaving Block Island four weeks earlier, although the incubation period has been reported to be as long as three months (6). Babesiosis is also endemic in Connecticut (8); however this patient’s only rural exposure was on Block Island. Although babesiosis has been reported from the west coast of the United States (5), patients infected with this west coast species tend to be serologically positive for B gibsoni but negative for B microti. As the tick vector is Ixodes dammini, the same vector for Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), it is not surprising that over 50% of patients from the northeastern United States with one infection may have serological evidence of coinfection (9). In addition, recent serosurveys indicate coinfection with ehrlichia also occurs (10). The areas of babesiosis endemicity appear to be growing. It may be only a matter of time before all areas endemic for Lyme disease will also be endemic for babesiosis, and, therefore, there may eventually be endemic areas of babesiosis in Canada.

When symptomatic, the clinical presentation is nonspecific, consisting of fever, rigors, headache, fatigue, nausea, myalgias and abdominal pain (1). Physical findings include fever, hepatomegaly, petechia and ecchymosis. Laboratory data may show thrombocytopenia, low hematocrit, evidence of hemolysis with increased reticulocytes, anemia, low haptoglobin, elevated transaminases, proteinuria and hemoglobinuria. With a history of a tick bite, Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, babesiosis and even the spotted fever rickettsioses must be considered depending on the exposure history. The diagnostic test for babesiosis is a peripheral smear demonstrating intracellular parasites. Serology is very specific and is helpful for epidemiology and retrospective confirmation (11).

Most infections with B microti appear to be subclinical; however, symptomatic infections are more likely in asplenic patients, individuals with pre-existing clinical disease and individuals over the age of 50 years. In one population survey, age was the strongest predictor of symptomatic disease (12). In immunocompetent patients who are symptomatic, disease is rarely life-threatening but can be very severe, warranting treatment. The recommended treatment is clindamycin 600 mg tid and quinine 650 mg tid orally for seven days. This treatment was fortuitously discovered when a patient with babesiosis was treated for what was initially thought to be transfusion-acquired malaria unresponsive to choroquine (13). For extremely ill patients with a high parasite load (more than 10%), exchange blood transfusion can be lifesaving (1). In our case, the patient was moderately ill, and although his disease may have been self-limited, we felt it prudent to treat him because he was continuing his drive back to Connecticut.

CONCLUSION

Clinicians need to be aware of diseases such as babesiosis that may be endemic elsewhere. Because of our mobile population, a thorough travel history is crucial, not only for return travellers, but for visitors to our locales.

ADDENDUM

Between the time of acceptance of this manuscript and publication, another patient with babesiosis, concurrently infected with Lyme disease, was reported in Ontario; this patient was diagnosed in July 1997 (14). Therefore, although that report was published first, this present case is a report of the first case diagnosed in Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boustani MR, Gelfand JA. Babesiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:611–5. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith T, Kilborne FL. Investigation into the nature, causation, and prevention of southern cattle fever. US Dept Agr Bur Anim Indust Bull. 1893;1:109–76. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skrabalo Z, Deanovi Z. Piroplasmosis in man: report on a case. Doc Med George Trop. 1957;9:11–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholtens RG, Braff EH, Healey GA, Gleason N. A case of babesiosis in man in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1968;17:810–3. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1968.17.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quick RE, Herwaldt BL, Thomford JW, et al. Babesiosis in Washington State: a new species of babesia? Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:284–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-4-199308150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pruthi RK, Marshall WF, Wiltsie JC, Persing DH. Human babesiosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:853–62. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63943-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loutan L, Rossier J, Zufferey G, et al. Imported babesiosis diagnosed as malaria. Lancet. 1993;342:749. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91744-7. (Lett) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krause PJ, Telford SR, Ryan R, et al. Geographical and temporal distribution of babesial infection in Connecticut. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.1-4.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benach JL, Coleman JL, Habicht GS, MacDonald A, Grunwaldt E, Giron JA. Serological evidence for simultaneous occurrences of Lyme disease and babesiosis. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:473–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magnarelli LA, Dumler JS, Anderson JF, Johnson RC, Fikrig E. Coexistence of antibodies to tick-borne pathogens of babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, and Lyme borreliosis in human sera. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3054–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.3054-3057.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krause PJ, Telford SR, Ryan R, Conrad PA, Wilson M, Thomford JW. Diagnosis of babesiosis: evaluation of a serologic test for the detection of Babesia microti antibody. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:923–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.4.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meldrum SC, Birkhead GS, White DJ, Benach JL, Morse DL. Human babesiosis in New York State: an epidemiological description of 136 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:1019–23. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.6.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wittner M, Rowin KS, Tanowitz HB, et al. Successful chemotherapy of transfusion babesiosis. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:601–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-5-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.dos Santos C, Kanin K. Concurrent babesiosis and Lyme disease diagnosed in Ontario. Can Commun Dis Rep. 1998;24:97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]