Abstract

Wound and subsequent healing are frequently associated with hypoxia. Although hypoxia induces angiogenesis for tissue remodeling during wound healing, it may also affect the healing response of parenchymal cells. Whether and how wound healing is affected by hypoxia in kidney cells and tissues is currently unknown. Here, we used scratch-wound healing and transwell migration models to examine the effect of hypoxia in cultured renal proximal tubular cells (RPTC). Wound healing and migration were significantly slower in hypoxic (1% oxygen) RPTC than normoxic (21% oxygen) cells. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) was induced during scratch-wound healing in normoxia, and the induction was more evident in hypoxia. Nevertheless, HIF-1α-null and wild-type cells healed similarly after scratch wounding. Moreover, activation of HIF-1α with dimethyloxalylglycine in normoxic cells did not suppress wound healing, negating a major role of HIF-1α in wound healing in this model. Scratch-wound healing was also associated with glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β)/β-catenin signaling, which was further enhanced by hypoxia. Pharmacological inhibition of GSK3β resulted in β-catenin expression, accompanied by the suppression of wound healing and transwell cell migration. Ectopic expression of β-catenin in normoxic cells could also suppress wound healing, mimicking the effect of hypoxia. Conversely, inhibition of β-catenin via dominant negative mutants or short hairpin RNA improved wound healing and transwell migration in hypoxic cells. The results suggest that GSK3β/β-catenin signaling may contribute to defective wound healing in hypoxic renal cells and tissues.

Introduction

Wound healing in tissues and organs is characterized by hypoxia, a condition of decreased availability of oxygen. Hypoxia in wounded tissues is caused in part by the vascular damage and decreased blood supply, but also, in a large part, by the O2 consumption of the cells in the wound that are metabolically activated for migration, proliferation, and wound healing (Tandara and Mustoe, 2004). Under this condition, hypoxia contributes to the stimulation of the angiogenesis and tissue remodeling by activating a myriad of signaling pathways and inducing key transcription factors such as hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) (Tandara and Mustoe, 2004). In wounded skin, hypoxia has also been shown to promote the migration of keratinocytes for restoration of the epithelium (Benizri et al., 2008). However, whether and how hypoxia affects wound healing in parenchymal cells in injured organs, such as the kidneys, is unknown.

HIF is a family of transcription factors that are induced by hypoxia to regulate gene expression (Semenza, 2007). Recent studies have further revealed HIF activation by nonhypoxic conditions or stimuli. HIF consists of α and β subunits. HIFβ is constitutively expressed, whereas HIFα is hydroxylated at several proline and asparagine sites in the presence of oxygen, targeting it for von Hippel-Lindau-mediated ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation. In hypoxia, the lack of oxygen prevents HIFα hydroxylation and degradation, leading to HIFα accumulation and dimerization with HIFβ to form a functional transcription factor (Semenza, 2007; Kaelin and Ratcliffe, 2008). Pharmacological inhibitors of HIFα prolyl hydroxylase, such as dimethyloxaloylglycine (DMOG), can suppress HIFα hydroxylation and induce HIFα under normoxia. During ischemia-reperfusion, an in vivo condition of hypoxia, HIF family members are induced to regulate tissue repair and remodeling. In kidneys, HIF-1 is induced in renal tubules, whereas HIF-2 is expressed by interstitial cells (Rosenberger et al., 2002; Sutton et al., 2008). Although HIF induction has been shown to protect kidney tissues against ischemic and nephrotoxic injury (Bernhardt et al., 2006; Weidemann et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2009), it remains unclear whether it does so by directly protecting renal tubular cells, promoting wound healing in these cells, or enhancing angiogenesis and tissue remodeling (Haase, 2006; Hill et al., 2008; Gunaratnam and Bonventre, 2009).

Another important signaling pathway that may contribute to the regulation of wound healing involves glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) and β-catenin. In unstimulated cells, β-catenin exists in a multiprotein complex with GSK3β, axin, and adenomatous polyposis coli. Phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK3β in the complex results in the degradation of β-catenin. Activation of Wnt signaling leads to GSK3β phosphorylation and inactivation, resulting in the accumulation of β-catenin, which may translocate into the nucleus to induce gene expression. GSK3β/β-catenin signaling plays a critical role in nephron formation in the early stage of kidney development (Carroll et al., 2005; Iglesias et al., 2007; Lyons et al., 2009). In adult kidneys, changes of GSK3β/β-catenin signaling in renal tubules, podocytes, and interstitial cells are associated with numerous kidney diseases, including acute kidney injury, diabetic nephropathy, renal cancers, cystic kidney diseases, albuminuria, and renal fibrosis (Pulkkinen et al., 2008; Dai et al., 2009; He et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009b, 2010). In kidney interstitial cells, β-catenin promotes fibrosis (He et al., 2009). In podocytes, β-catenin promotes podocyte dysfunction, inducing albuminuria, and blockade of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by paricalcitol ameliorates adriamycin-induced proteinuria and kidney injury (Dai et al., 2009; He et al., 2011). In renal tubular cells, β-catenin promotes cell survival by inhibiting Bax, a well documented proapoptotic protein, whereas GSK3β promotes tubular apoptosis after acute ischemic kidney injury (Wang et al., 2009b, 2010). Although these studies have suggested a role of GSK3β/β-catenin signaling in acute kidney cell injury, whether and how this signaling pathway contributes to kidney repair or wound healing after initial injury remains poorly understood.

In this study, we first demonstrated the inhibitory effect of hypoxia on wound healing in renal tubular cells. We then examined the roles played by HIF-1 and GSK3β/β-catenin signaling in the wound-healing defect of hypoxic cells. The results suggest that GSK3β/β-catenin signaling, but not HIF, contributes to the wound-healing defect of renal proximal tubular cells during hypoxia.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Special Reagents.

Antibodies were purchased from the following sources: polyclonal anti-β-catenin, antiphospho-GSK3β-ser9, and anti-total-GSK3β from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), monoclonal anti-HIF-1α from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), the secondary antibodies for immunoblot analysis from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, PA), and the secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Lithium chloride (LiCl), 3-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione (SB216763), and DMOG were purchased from Acros Organics (Fairlawn, NJ), Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO), and Sigma (St. Louis, MO), respectively.

Cell Culture.

Immortalized rat kidney proximal tubular cells (RPTC) were originally obtained from Dr. Ulrich Hopfer (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH). Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Wild-type and HIF-1α-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were obtained from Dr. Gregg Semenza (The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) (Zhang et al., 2008).

Hypoxic Incubation.

RPTC were plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells/35-mm dish or 2.5 × 106 cells/60-mm dish to grow overnight for experiment. Hypoxia treatment was conducted in a hypoxia chamber as described previously (Wang et al., 2006). In brief, dishes with cells were transferred into a hypoxia chamber (COY Laboratory Products, Ann Arbor, MI) containing 1% oxygen. The oxygen tension in the chamber was monitored and maintained by a computerized sensor probe. Humidity was maintained with a humidifier.

Scratch-Wound Healing Assay.

For morphological examination, a scratch-wound healing model was modified from Zhuang et al. (2011). In brief, a monolayer of confluent RPTC grown in a 35-mm dish was linearly scratched with a sterile 1000-μl pipette tip. Phase-contrast images were recorded at 0 and 18 h after scratching. The width of the wound was measured at various time points to determine the healed distance. For biochemical analysis, multiple uniformed wounds were created in a RPTC monolayer in 60-mm dishes with a wounding device that makes concentric circular 130-μm-wide cell bands separated by 750-μm-wide wounds (Lan et al., 2010). Whole-cell lysate was collected at different time points after wounding for immunoblot analysis.

Transwell Cell Migration Assay.

Transwell cell migration was measured as described previously (Wang et al., 2009a). In brief, the undersurfaces of transwells (Costar; Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA) were coated with 10 μg/ml collagen I (Millipore) overnight at 4°C. Coated wells were then placed into a 24-well plate containing 600 μl of culture medium. RPTC were detached and suspended at 1.5 × 106 cells/ml in culture medium. The cells were then added into transwells (200 μl, 3 × 105 cells/well) and allowed to migrate for 6 h at 37°C. Cotton swabs were used to remove cells in the upper surface of the transwells, and migratory cells attached on the undersurface were stained with propidium iodide (PI). The numbers of migrated cells were counted by using an inverted microscope. To determine the effect of GSK3 inhibitors on cell migration, the inhibitors were added in the bottom-chamber medium. To determine the effect of β-catenin knockdown on cell migration, cells were infected with lentivirus containing scramble or β-catenin-short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequence for 3 days before adding them to the transwell for cell migration assay.

Lentivirus-Mediated β-Catenin Overexpression.

A mouse β-catenin cDNA plasmid (gift from Dr. Lin Mei, Georgia Health Sciences University, Augusta, GA) was used as the template for polymerase chain reaction-based deletion to generate active β-catenin (β-catenin152–781) and dominant negative β-catenin (β-catenin152–694), which were subcloned into the lentiviral vector pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-copGFP (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) at Xbal and Not1 sites. The β-catenin plasmids were cotransfected into 293FT cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with three packaging plasmids (pLP1, pLP2, and pLP/VSV-G) to collect the culture medium at 48 h. The culture medium with packaged lentivirus was added to RPTC for 1 day of infection. The medium was then replaced with fresh medium for an additional 2 days of culture before the wound-healing test.

Lentiviral shRNA-Mediated β-Catenin Knockdown.

Lentiviral shRNA plasmid targeting β-catenin and a scrambled nontargeting control plasmid were made by using the pLV-mU6-EF1a-GFP vector (Biosettia, San Diego, CA). The target sequence of the β-catenin shRNA was GCTGACCAAACTGCTAAATGA. The lentivirus package and transduction methods were the same as those described above for lentivirus-mediated β-catenin overexpression.

Immunofluorescence.

RPTC grown on glass coverslips were scratch-wounded with a sterile 1000-μl pipette tip and incubated in hypoxia or normoxia for 6 h. Then the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100 in a blocking buffer. The cells were then exposed to β-catenin antibody, followed by incubation with Cy3-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. After washes, the coverslips were mounted on slides with Antifade for examination by fluorescence microscopy using the Cy3 channel.

Immunoblot Analysis.

Protein concentration was determined by using the BCA reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each well for electrophoresis by using the NuPAGE Gel System (Invitrogen), followed by transferring them onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The blots were then incubated in blocking buffer for 1 h, then in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washes, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, and the antigens on the blots were revealed by using the enhanced chemiluminescence kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Statistical Analysis.

Quantitative data were expressed as means ± S.D. (n ≥4). Statistical differences between two groups were determined by Student's t test. p < 0.05 was considered significantly different. Qualitative results, including immunoblots, were representatives of at least three separate experiments.

Results

Hypoxia Inhibits Scratch-Wound Healing and Migration in RPTC.

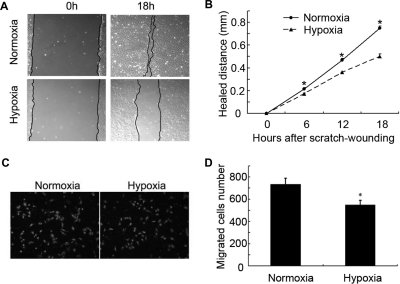

Ischemia or hypoxia is a common feature of injured tissues, including kidneys (Haase, 2006; Gunaratnam and Bonventre, 2009). Whether and how wound healing is affected by hypoxia is largely unknown. We examined the effect of hypoxia in a scratch-wound healing model of cultured RPTC. In this model, RPTC were scratch-wounded with a sterile pipette tip and then incubated in hypoxia (1% O2) or normoxia (21% O2) for recovery or healing. Wounds were recorded and measured immediately after scratching (0 h) and at different time points postscratching. Representative wounds are shown in Fig. 1A. Under normoxia, most of the wound healed within 18 h. In contrast, a significant wound remained in the cells recovered under hypoxia. Measurement of the healed distance showed that wound healing was suppressed by hypoxia in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Hypoxia inhibits scratch-wound healing and transwell migration in RPTC. A and B, scratch-wound healing. RPTC were scratch-wounded with a sterile pipette tip and then incubated under hypoxia (1% O2) or normoxia (21% O2). A, representative wounds immediately after scratch wounding and after 18 h of healing were recorded with a phase-contrast microscope. B, the wound width was measured at 6, 12, and 18 h after scratching to determine the healed distance. C and D, transwell migration. A total of 3 × 105 cells were added to each transwell insert, which was put in a 24-well plate with 600 μl of culture medium in normoxia or hypoxia for 6 h. C, representative PI staining of migratory cells was recorded with a fluorescence microscope. D, migratory cells attached on the undersurface were counted after PI staining. In B and D, data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus normoxia.

In the scratch model, wound healing involves a rapid mobilization of the wound edge cells to migrate into the wound. We hypothesized that hypoxia might suppress wound healing in part by blocking cell migration. To test this possibility, we determined the effect of hypoxia on cell migration by using the transwell cell migration assay (Zhuang et al., 2011). RPTC were seeded in transwell inserts, which were then placed in the wells of 24-well plates containing culture medium under normoxia or hypoxia. The cells that migrated to the undersurface of the transwell inserts were recorded after PI staining and counted. As shown in Fig. 1C, apparently fewer cells migrated under hypoxia than under normoxia. Cell counting showed that in 6 h ∼720 cells migrated under normoxia, whereas ∼520 did so under hypoxia (Fig. 1D).

HIF-1α Induction during Wound Healing.

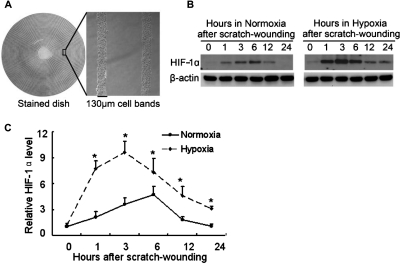

To understand the mechanism of wound-healing defects in hypoxic cells, we initially focused on HIFs, which mediate a variety of cellular responses to hypoxia (Semenza, 2007). Multiple circular wounds were created in RPTC with a “stamp wounding” device (Lan et al., 2010), which generated multiple uniformed wounds in the cell layer (Fig. 2A). After wounding, the cells were incubated under normoxia or hypoxia for various durations of healing. As shown in Fig. 2B, left, HIF-1α was induced during wound healing in normoxic RPTC. The induction was detectable at 1 h postwounding, further increased at 3 and 6 h, and then decreased. In hypoxia, HIF-1α induction during wound healing was stronger and lasted longer (Fig. 2B, right). A marked HIF-1α induction was detected at 1 h postwounding in hypoxic cells, and the induction reached the highest level at 3 h. Thereafter HIF-1α decreased but it remained higher than the basal level at 24 h (Fig. 2B, right). The time-dependent changes in HIF-1α expression during scratch-wound healing were further confirmed by quantification via densitometry (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

HIF-1α induction during wound healing in normoxia and hypoxia. A, multiple uniform wounds made with a wounding device. RPTC grown in 60-mm dishes were pressed with a multiple-wounding device to induce concentric circular cell bands of 130-μm width separated by wounds of 750-μm width. B, time-dependent HIF-1α induction during wound healing in normoxia and hypoxia. RPTC in 60-mm dishes were wounded by the multiple-wounding device and then incubated in normoxia or hypoxia to collect whole-cell lysates at different time points for immunoblot analysis of HIF-1α and β-actin. C, densitometric analysis of HIF-1α expression during scratch-wound healing. Immunoblots from three separate experiments were analyzed by densitometry, and the signal of HIF-1α was normalized with control (0 h) that was arbitrarily set as 1. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 versus normoxia.

Pharmacological Induction of HIF Does Not Block Wound Healing.

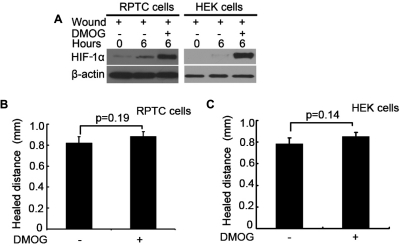

Wound healing was defective in hypoxic cells (Fig. 1) that had a notable HIF-1α induction (Fig. 2B), suggesting that HIF-1 may contribute to the wound-healing defects under hypoxia. To test this possibility, we first determined the effects of DMOG, a pharmacological inducer of HIF that prevents HIF-1α degradation under normoxia by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylases (Fraisl et al., 2009). It was reasoned that, if hypoxia suppresses wound healing via HIF induction, then HIF induction by DMOG may block wound healing in normoxic cells. Our pilot experiments titrated the condition of DMOG treatment. As shown in Fig. 3A, 6 h of wound healing led to HIF-1α induction in both RPTC and HEK cells under normoxia, which was dramatically enhanced by DMOG. Despite marked HIF-1 induction, DMOG did not attenuate wound healing in either RPTC or HEK cells; instead it slightly improved wound healing in these cells (Fig. 3, B and C). The results therefore do not support the hypothesis that HIF induction accounts for the wound-healing defects in hypoxic cells.

Fig. 3.

DMOG induces HIF-1α without affecting wound healing. A, RPTC and HEK cells were wounded with the multiple-wounding device and incubated in full medium without (−) or with (+) 100 mM DMOG in normoxia for 6 h to collect whole-cell lysates for immunoblot analysis of HIF-1α. B and C, scratch-wound healing. RPTC and HEK cells were scratch-wounded and then incubated in normoxia without (−) or with (+) 100 mM DMOG for 18 h to measure the healed distance. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 6).

Wound Healing Is Not Affected by HIF-1 Deficiency in MEF Cells.

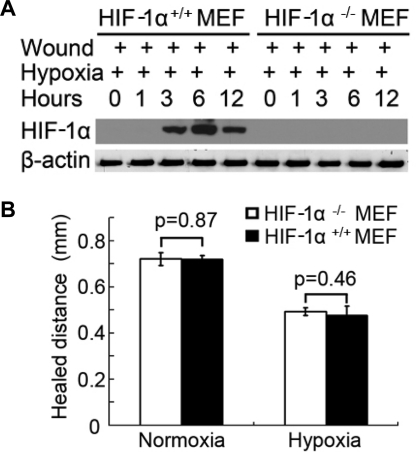

To further delineate the role of HIF in wound healing, we compared wild-type [HIF-1α(+/+)] and HIF-1α-null [HIF-1α(−/−)] MEFs. As expected, HIF-1α was induced by hypoxia during wound healing in HIF-1α(+/+) MEF cells, but not in HIF-1α(−/−) cells (Fig. 4A). When these two genotype cells were subjected to scratch wounding, their healing was very similar in both normoxia and hypoxia (Fig. 4B). The results suggest that HIF-1 does not play a critical role in wound healing in this cellular model.

Fig. 4.

Wound healing in HIF-1α-null cells. A, HIF-1α induction during wound healing in hypoxia in HIF-1α-null [HIF-1α(−/−)] and wild-type [(HIF-1α(+/+)] MEF cells. MEF cells were wounded by the multiple-wound device and incubated in hypoxia to collect whole-cell lysates at different time points for immunoblot analysis of HIF-1α and β-actin. B, scratch-wound healing. Wild-type and HIF-1α-null MEF cells were scratch-wounded and then incubated in hypoxia for 18 h to measure the healed distance. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 6).

Activation of GSK3β/β-Catenin Signaling during Wound Healing.

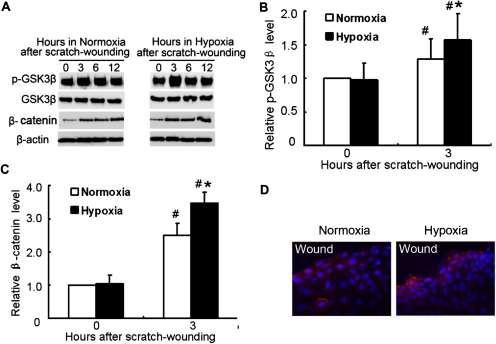

In the canonical pathway of GSK3β/β-catenin signaling, GSK3β phosphorylates β-catenin, leading to its degradation. GSK3β/β-catenin signaling plays an important role in wound healing (Cheon et al., 2002). In normoxic RPTC, wound healing induced GSK3β phosphorylation at serine-9 (indicative of GSK3β inactivation), which was accompanied by increased expression of β-catenin (Fig. 5A, left). GSK3β phosphorylation and β-catenin expression were also induced during wound healing in hypoxic cells (Fig. 5A, right). It is noteworthy that compared with normoxic cells hypoxic cells showed higher GSK3β phosphorylation at 3 h postwounding and higher β-catenin expression at all time points examined (Fig. 5, A–C). We further examined β-catenin expression by immunofluorescence (Fig. 5D). Under normoxia, some of the cells at the wound edge showed an increase in β-catenin staining. Under hypoxia, β-catenin staining was detected in more cells and seemed to be more intense. It was noted that in some of the hypoxic cells β-catenin staining appeared in nuclei, in addition to plasma membrane and cytoplasm (Fig. 5D, right). Together, these data demonstrated an enhanced GSK3β/β-catenin signaling in hypoxic cells.

Fig. 5.

GSK3β and β-catenin expression during wound healing in RPTC. A, GSK3β phosphorylation and β-catenin induction during wound healing in RPTC under normoxia and hypoxia. RPTC were wounded by the multiple-wound device and incubated in normoxia or hypoxia to collect whole-cell lysates at different time points for immunoblot analysis of serine-15-phosphorylated and total GSK3β, β-catenin, and β-actin. B and C, densitometric analysis of p-GSK3β and β-catenin induction during 3 h of wound healing. The signals of p-GSK3β and β-catenin in the immunoblots from three separate experiments were analyzed by densitometry and normalized with control (0 h). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). #, p < 0.05 versus control; *, p < 0.05 versus 3 h after scratch wounding in normoxia. D, immunofluorescence analysis of β-catenin expression. PRTC cells were subjected to 6 h of scratch-wound healing under normoxia or hypoxia. The cells were fixed for immunofluorescent staining of β-catenin (red) and nuclear staining with Hoechst33342 (blue).

GSK3β Inhibitors Suppress Wound Healing.

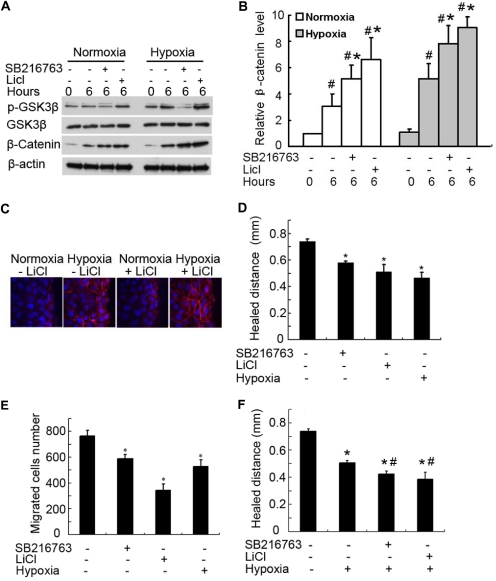

Based on the above observations (Fig. 5), we hypothesized that the enhanced GSK3β/β-catenin signaling may contribute to wound-healing defects in hypoxic cells. To test this possibility, we determined the effects of GSK3β inhibitors on wound healing. The rationale is that if hypoxia suppresses wound healing by blocking GSK3β, resulting in β-catenin activation, then similar effects would be induced by inhibitors of GSK3β. We first titrated the concentrations of two GSK3β inhibitors and found that 10 mM LiCl and 10 μM SB216763 could effectively induce β-catenin expression in both normoxia and hypoxia (Fig. 6, A and B). By immunofluorescence, we further confirmed the induction of β-catenin by these GSK3β inhibitors (shown in Fig. 6C for LiCl effect). It is noteworthy that both LiCl and SB216763 suppressed scratch-wound healing and transwell cell migration in normoxia (Fig. 6, D and E). We further examined the effects of these inhibitors on wound healing in hypoxia. As shown in Fig. 6F, whereas hypoxia per se suppressed wound healing markedly, the GSK3β inhibitors exerted marginal additive effects, suggesting that GSK3β/β-catenin signaling is a major, but not the only, pathway that contributes to the wound-healing defects of hypoxic cells.

Fig. 6.

GSK3β inhibitors suppress wound healing. A and B, β-catenin up-regulation by GSK3β inhibitors. RPTC were scratch-wounded and then incubated for 6 h in normoxia or hypoxia with or without 10 mM LiCl or 10 μM SB216763. A, whole-cell lysate was collected for immunoblot analysis of serine-9-phosphorylated GSK3β, total GSK3β, β-catenin, and β-actin. B, densitometric analysis of β-catenin expression. The signal of β-catenin in the immunoblots from three separate experiments was analyzed by densitometry and normalized with control (0 h). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). #, p < 0.05 versus control; *, p < 0.05 versus 6 h of scratch-wound healing without inhibitors. C, another group of cells was fixed for immunofluorescent staining of β-catenin (red) and nuclear staining with Hoechst33342 (blue). D, suppression of wound healing in normoxia by GSK3β inhibitors. RPTC were scratch-wounded and incubated in normoxia with or without 10 mM LiCl and 10 μM SB216763 for 18 h to measure the healed distance. E, suppression of cell migration in normoxia by GSK3β inhibitors. A total of 3 × 105 RPTC were seeded in a transwell insert, which was put in a 24-well plate containing 600 μl of medium with or without 10 mM LiCl and 10 μM SB216763 in normoxia for 6 h. The cells that migrated to the undersurface of the insert were stained with PI and counted. F, effect of GSK3β inhibitors on wound healing in hypoxia. RPTC were scratch-wounded and incubated in hypoxia with or without 10 mM LiCl and 10 μM SB216763 for 18 h to measure the healed distance. In D to F, data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus control; #, p < 0.05 versus hypoxia-only group.

Active β-Catenin Suppresses and Dominant Negative β-Catenin Enhances Wound Healing.

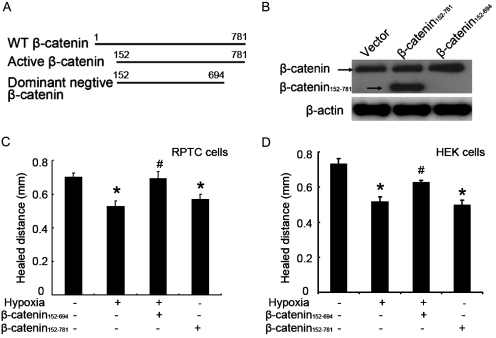

The above results (Fig. 6) suggest that GSK3β inhibitors may induce β-catenin to suppress wound healing. To directly examine the role of β-catenin on wound healing, we determined the effects of stable active-β-catenin (β-catenin152–781) or dominant negative β-catenin (β-catenin152–694). β-Catenin undergoes degradation after GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation at the N terminus. β-Catenin152–781 is resistant to GSK3β-mediated degradation due to the deletion of the N-terminal 151 amino acid residues, including the GSK3β phosphorylation sites, and as a result, it functions as active β-catenin when expressed in cells. In contrast, β-catenin152–694 has an additional deletion at the C terminus that is critical to the gene transcription activity of β-catenin and therefore functions as a dominant-negative mutant in cells (Fig. 7A). These constructs have been used to determine the role of β-catenin in renal tubular cell death or survival (Wang et al., 2009b). After transfection into HEK cells, the expression of β-catenin152–781 was detected by the β-catenin antibody that recognized C terminus of this protein, where β-catenin152–694 was not detected by this antibody because of its C-terminal deletion (Fig. 7B). Consistent with previous results (Fig. 1), hypoxia suppressed scratch-wound healing in both RPTC and HEK cells. This suppressive effect of hypoxia was blocked by dominant-negative β-catenin152–694. In addition, active β-catenin152–781 could suppress wound healing in normoxic cells (Fig. 7, C and D). These results suggest that β-catenin is inhibitory to wound healing, and its induction by hypoxia may partially account for the wound-healing defects in hypoxic cells.

Fig. 7.

Active β-catenin suppresses and dominant negative β-catenin enhances wound healing. RPTC and HEK cells were infected with empty virus (EV), active-β-catenin virus (β-catenin152–781), or dominant negative β-catenin virus (β-catenin152–694). A, diagram of wild type (WT) and deletion β-catenin mutants. B, β-catenin expression after lentivirus-mediated infection in HEK cells. Whole-cell lysates were collected for immunoblot analysis using an antibody recognizing the C terminus of β-catenin. C and D, scratch-wound healing. RPTC and HEK cells after lentiviral infection were scratch-wounded and incubated in normoxia or hypoxia for 18 h to measure the healed distance. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus normoxia with empty virus group; #, p < 0.05 versus hypoxia with empty virus group.

β-Catenin Knockdown Abrogates Wound-Healing Defects in Hypoxic Cells.

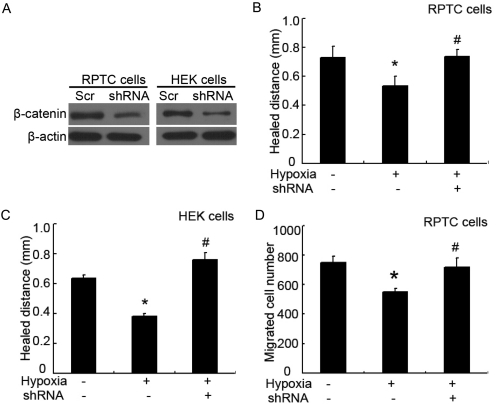

To further establish the role of β-catenin in wound-healing defects in hypoxia, we tested the effect of β-catenin knockdown with shRNA. RPTC and HEK cells were infected with lentivirus containing β-catenin-shRNA or scrambled control sequence, followed by scratch wounding or transwell migration assay. By immunoblot analysis, we confirmed that β-catenin-shRNA, but not the scrambled sequence, reduced β-catenin expression in both RPTC and HEK cells (Fig. 8A). It is noteworthy that although hypoxia suppressed wound healing in scrambled sequence-transfected cells, the suppressive effect was reversed by shRNA-mediated β-catenin knockdown (Fig. 8, B and C). In addition, migration defect of hypoxic cells was prevented by β-catenin shRNA (Fig. 8D). The restoration of wound healing and migration in hypoxic cells by knocking down β-catenin supports a role for β-catenin in wound-healing defects in hypoxia.

Fig. 8.

Knockdown of β-catenin restores wound healing in hypoxic cells. RPTC and HEK cells were infected with lentivirus containing scramble control sequence (Scr) or β-catenin shRNA sequence (shRNA). A, knockdown effect of β-catenin shRNA. After infection, whole-cell lysates were collected for immunoblot analysis of β-catenin. B and C, scratch-wound healing. After lentivirus infection, RPTC and HEK cells were scratch-wounded and incubated in normoxia or hypoxia for 18 h to measure the healed distance. D, transwell cell migration. After lentivirus infection, 3 × 105 RPTC were seeded in a transwell insert, which was then put in a 24-well plate containing culture medium in normoxia for 6 h. The cells that migrated to the undersurface were stained with PI and counted. In B to D, data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 6). *, p < 0.05 versus normoxia; #, p < 0.05 versus hypoxia without β-catenin shRNA (with scrambled sequence).

Discussion

Wound healing in tissues and organs is characterized by hypoxia. However, the effect of hypoxia on wound healing is not well understood. On one hand, hypoxia stimulates angiogenesis and tissue remodeling for healing; on the other hand, lack of oxygen may adversely affect parenchymal cells to prevent the repair of the wound. In this study, we have used cell culture models to examine the effect of hypoxia on wound healing in renal tubular cells. The results demonstrate that wound healing is impaired in hypoxic cells. Mechanistically, GSK3β/β-catenin signaling, but not HIF-1, seems to contribute to the wound-healing defect.

A renoprotective role of HIF has been suggested during acute kidney injury. Hill et al. (2008) showed that pharmacological activation of HIF by DMOG protected against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Weidemann et al. (2008) further showed that hypoxic preconditioning protected renal tubular cells against cisplatin injury by inducing HIF. The preconditioning effect of HIF was also reported to ameliorate ischemic kidney injury and renal failure (Bernhardt et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009). Despite these reports, the mechanism underlying the renoprotective effect of HIF remains unclear. In cultured renal tubular cells, the cytoprotective effect of hypoxia was shown to be HIF-independent, suggesting that HIF may not directly protect renal parenchymal cells (Wang et al., 2006). The results of the present study further indicate that HIF may not play a major regulatory role in the wound-healing response of renal tubular cells. This conclusion is supported by the observation that scratch-wound healing was not significantly affected by either pharmacological activation of HIF or genetic deletion of HIF-1 (Figs. 3 and 4). It is noteworthy that these are in vitro experiments using cultured cells, and it is important to determine whether HIF regulates parenchymal cell recovery and regeneration during kidney repair in vivo. In addition to parenchymal cell regulation, HIF may participate in kidney repair by inducing angiogenesis and the development of renal fibrosis (Higgins et al., 2007).

The role of GSK3β/β-catenin in wound healing is very complex and varies between cell and tissue types. β-catenin inhibited keratinocyte migration and activated fibroblast proliferation, causing aggressive fibromatosis and hyperplasia in cutaneous wounds (Cheon et al., 2002). In chronic ulcers, β-catenin was shown to be induced in the nonhealing epidermal edge to inhibit keratinocyte migration and dedifferentiation, resulting in impaired healing. Consistently, β-catenin inhibited epithelial cell migration in wounds in a human skin organ culture model (Stojadinovic et al., 2005). In contrast, other studies have suggested that β-catenin promotes proliferation and repair. For example, during the repair of bone fracture β-catenin positively regulated osteoblasts, and activation of β-catenin by lithium treatment improved fracture healing (Chen et al., 2007). In kidney injury models, GSK3β/β-catenin signaling has been studied mainly in the injury phase. Price et al. (2002) reported that β-catenin and T-cell factor proteins transiently accumulated in the nucleus in response to sublethal renal ischemic injury. Wang et al. (2010) demonstrated that inhibition of GSK3β protected kidney tubular cells from ischemic injury by inhibiting tubular cell apoptosis. Moreover, β-catenin overexpression promoted survival of renal tubular cells by inhibiting Bax (Wang et al., 2009b). In podocytes, however, β-catenin was shown to promote cell injury and dysfunction during adriamycin-induced kidney injury (Dai et al., 2009; He et al., 2011). In these studies, whether GSK3β/β-catenin signaling regulates the wound-healing response of parenchymal kidney cells was not examined. Our current results demonstrate GSK3β inactivation with concurrent β-catenin induction during wound healing in renal tubular cells, indicative of the activation of GSK3β/β-catenin signaling. It is noteworthy that inhibition of GSK3β and β-catenin activation or overexpression can suppress wound healing and cell migration, suggesting that GSK3β/β-catenin signaling antagonizes wound healing in renal tubular cells. Considering the published work reporting the protective role of β-catenin (Wang et al., 2009b), it is suggested that β-catenin may play a dual role in kidney injury: protecting against tubular cell injury but suppressing kidney repair during recovery. If proven true in vivo, inhibition of GSK3β and consequent activation of β-catenin may offer a useful therapeutic strategy when administered before and during kidney injury; however, it would be important to suppress β-catenin during subsequent kidney repair. Obviously, it is important to investigate the distinct roles played by GSK3β/β-catenin signaling during kidney injury and repair phases.

We demonstrated β-catenin expression in the cells at the wound edge (Fig. 5D). Our immunoblot analysis further showed that β-catenin expression was accompanied by GSK3β phosphorylation or inactivation, suggesting the involvement of the canonical Wnt/GSK3β pathway in β-catenin activation during wound healing. Consistently, in cutaneous wounds β-catenin expression is not associated with a change in its mRNA level, but correlates with GSK3β phosphorylation or inactivation (Cheon et al., 2005). Upon activation, β-catenin inhibited wound healing in renal tubular cells (Figs. 7 and 8); however, the underlying mechanism is currently unclear. β-Catenin activates multiple target genes that potentially promote epithelial cell survival, including insulin-like growth factor II, Akt, inhibitor of apoptosis proteins, proliferin, and Wnt-1-β-catenin-secreted proteins 1 and 2 (Longo et al., 2002; Dihlmann et al., 2005). It is noteworthy that, in addition to the cell survival effects, β-catenin is an important integrator of cell proliferation and differentiation (Brembeck et al., 2006), and, as a result, inappropriate activation of β-catenin and downstream proteins may lead to deregulation of proliferation and differentiation, resulting in impaired wound healing. In line with this possibility, Stojadinovic et al. (2005) reported that β-catenin accumulated in the nucleus of keratinocytes at the nonhealing wound edge of chronic ulcers, leading to c-myc expression and resulting in cellular hyperproliferation and inhibition of migration and wound healing. In our study, cell migration was also suppressed when β-catenin expression was elevated with GSK3β inhibitors (Fig. 6E). Several mechanisms may account for the inhibitory effect of β-catenin on cell migration. It was reported that β-catenin was elevated in mesenchymal cells during the proliferative phase. In hyperplastic wounds there was a prolonged duration of β-catenin elevation, maintaining the mesenchymal cells in a prolonged proliferative state that may prevent the cells from entering into the migration state (Cheon et al., 2005). In addition, β-catenin is known to be a key component of adherens junctions, which are required to disassemble to allow cell migration (Nelson and Nusse, 2004). β-Catenin activation may enhance the adherens junctions to suppress migration. Furthermore, β-catenin may inhibit cell migration by regulating gene expression. In this regard, Stojadinovic et al. (2005) reported that β-catenin can suppress the expression of cytoskeletal components K6/K16 keratins that are important for keratinocyte migration in chronic wounds.

The observations the β-catenin was inhibitory in wound healing of renal tubular cells (Figs. 7 and 8) and hypoxia further activated β-catenin (Figs. 5 and 6) suggest that GSK3β/β-catenin signaling may contribute to impaired wound healing in hypoxic tubular cells. Indeed, blockade of β-catenin via dominant negative mutants and shRNAs could restore wound healing and cell migration during hypoxia (Figs. 7 and 8). It remains unclear how β-catenin is induced by hypoxia in RPTC during wound healing. Mazumdar et al. (2010) showed that hypoxia could not induce β-catenin in HIF-1α-null embryonic stem cells, suggesting a role of HIF-1 in β-catenin induction during hypoxia. However, in our study wound healing was not affected by HIF-1α deficiency, negating the involvement of HIF in wound-healing signaling, including β-catenin. Alternatively, hypoxic induction of β-catenin may be mediated by GSK3β inactivation. This possibility is supported by our observation that β-catenin induction during hypoxic wound healing was accompanied by GSK3β inactivation (indicated by phosphorylation at serine-9) (Fig. 6). In this regard, GSK3β is known to be modulated by Akt (Patel and Woodgett, 2008), a key signaling kinase that has been reported to be activated by hypoxia in renal tubular cells (Zeng et al., 2008). Consistently, we demonstrated significantly higher Akt activation during wound healing in hypoxic tubular cells than normoxic cells (data not shown). Thus we speculate that hyperactivation of Akt by wound healing in hypoxic cells may inactivate GSK3β, inducing β-catenin to prevent wound healing in renal tubular cells under hypoxia.

Our results showed that β-catenin was expressed in nucleus in some of the wound edge cells, suggesting the translocation and transcriptional activation of β-catenin. β-Catenin in nucleus can bind to lymphoid enhancer factor/T-cell factor, leading to increase in target gene expression. Consistently, β-catenin was shown to be transcriptionally active in mesenchymal cells during the proliferative phase of wound healing, as demonstrated by activation of a reporter construct in primary cell cultures and up-regulation of the β-catenin target genes: matrix metalloproteinase 7 and fibronectin (Cheon et al., 2005). Moreover, β-catenin and downstream target gene c-myc expression in keratinocytes inhibited epithelialization during wound healing in chronic wounds (Stojadinovic et al., 2005). It would be interesting to investigate the downstream transcriptional targets of β-catenin in renal tubular cells that affect wound healing in kidney tissues.

In conclusion, this study has determined the roles played by HIF-1α and GSK3β/β-catenin signaling during wound healing in renal tubular cells. Both HIF-1α and β-catenin are induced during wound healing in normoxic cells. Hypoxia leads to further activation of HIF-1α and β-catenin, which is accompanied by impaired wound healing. GSK3β/β-catenin signaling, but not HIF-1α, seems to contribute to the wound-healing defect in hypoxic cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Steven Borkan (Boston University, Boston, MA) and Dr. Lin Mei (Georgia Health Sciences University, Augusta. GA) for β-catenin plasmids; and Dr. Gregg Semenza (The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) for HIF-1α-null and wild-type MEF cell lines.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [Grants DK-058831, DK-087843] and a VA Merit grant.

J.P. is an exchange graduate student conducting thesis research at Georgia Health Sciences University, as part of the International Cooperative Agreement between Georgia Health Sciences University and Wuhan University in China.

Z.D. is a Research Career Scientist of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

- HIF

- hypoxia-inducible factor

- DMOG

- dimethyloxalylglycine

- GSK3β

- glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- RPTC

- renal proximal tubular cells

- LiCl

- lithium chloride

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- PI

- propidium iodide

- SB216763

- 3-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Peng and Dong.

Conducted experiments: Peng and Dong.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Ramesh and Sun.

Performed data analysis: Peng and Dong.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Peng, Ramesh, Sun, and Dong.

References

- Benizri E, Ginouvès A, Berra E. (2008) The magic of the hypoxia-signaling cascade. Cell Mol Life Sci 65:1133–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt WM, Câmpean V, Kany S, Jürgensen JS, Weidemann A, Warnecke C, Arend M, Klaus S, Günzler V, Amann K, et al. (2006) Preconditional activation of hypoxia-inducible factors ameliorates ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 17:1970–1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brembeck FH, Rosário M, Birchmeier W. (2006) Balancing cell adhesion and Wnt signaling, the key role of β-catenin. Curr Opin Genet Dev 16:51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll TJ, Park JS, Hayashi S, Majumdar A, McMahon AP. (2005) Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev Cell 9:283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Whetstone HC, Lin AC, Nadesan P, Wei Q, Poon R, Alman BA. (2007) β-Catenin signaling plays a disparate role in different phases of fracture repair: implications for therapy to improve bone healing. PLoS Med 4:e249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon S, Poon R, Yu C, Khoury M, Shenker R, Fish J, Alman BA. (2005) Prolonged β-catenin stabilization and tcf-dependent transcriptional activation in hyperplastic cutaneous wounds. Lab Invest 85:416–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon SS, Cheah AY, Turley S, Nadesan P, Poon R, Clevers H, Alman BA. (2002) β-Catenin stabilization dysregulates mesenchymal cell proliferation, motility, and invasiveness and causes aggressive fibromatosis and hyperplastic cutaneous wounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:6973–6978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, Stolz DB, Kiss LP, Monga SP, Holzman LB, Liu Y. (2009) Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes podocyte dysfunction and albuminuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 20:1997–2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dihlmann S, Kloor M, Fallsehr C, von Knebel Doeberitz M. (2005) Regulation of AKT1 expression by β-catenin/Tcf/Lef signaling in colorectal cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 26:1503–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraisl P, Aragonés J, Carmeliet P. (2009) Inhibition of oxygen sensors as a therapeutic strategy for ischaemic and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:139–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunaratnam L, Bonventre JV. (2009) HIF in kidney disease and development. J Am Soc Nephrol 20:1877–1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase VH. (2006) Hypoxia-inducible factors in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291:F271–F281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Dai C, Li Y, Zeng G, Monga SP, Liu Y. (2009) Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes renal interstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20:765–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Kang YS, Dai C, Liu Y. (2011) Blockade of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by paricalcitol ameliorates proteinuria and kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22:90–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DF, Kimura K, Bernhardt WM, Shrimanker N, Akai Y, Hohenstein B, Saito Y, Johnson RS, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, et al. (2007) Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 117:3810–3820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill P, Shukla D, Tran MG, Aragones J, Cook HT, Carmeliet P, Maxwell PH. (2008) Inhibition of hypoxia inducible factor hydroxylases protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:39–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias DM, Hueber PA, Chu L, Campbell R, Patenaude AM, Dziarmaga AJ, Quinlan J, Mohamed O, Dufort D, Goodyer PR. (2007) Canonical WNT signaling during kidney development. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293:F494–F500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG, Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. (2008) Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell 30:393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan R, Geng H, Hwang Y, Mishra P, Skloss WL, Sprague EA, Saikumar P, Venkatachalam M. (2010) A novel wounding device suitable for quantitative biochemical analysis of wound healing and regeneration of cultured epithelium. Wound Repair Regen 18:159–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo KA, Kennell JA, Ochocinska MJ, Ross SE, Wright WS, MacDougald OA. (2002) Wnt signaling protects 3T3–L1 preadipocytes from apoptosis through induction of insulin-like growth factors. J Biol Chem 277:38239–38244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons JP, Miller RK, Zhou X, Weidinger G, Deroo T, Denayer T, Park JI, Ji H, Hong JY, Li A, et al. (2009) Requirement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in pronephric kidney development. Mech Dev 126:142–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Lim T, Xu J, Tang H, Wan Y, Zhao H, Hossain M, Maxwell PH, Maze M. (2009) Xenon preconditioning protects against renal ischemic-reperfusion injury via HIF-1α activation. J Am Soc Nephrol 20:713–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar J, O'Brien WT, Johnson RS, LaManna JC, Chavez JC, Klein PS, Simon MC. (2010) O2 regulates stem cells through Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Nat Cell Biol 12:1007–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WJ, Nusse R. (2004) Convergence of Wnt, β-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science 303:1483–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Woodgett J. (2008) Glycogen synthase kinase-3 and cancer: good cop, bad cop? Cancer Cell 14:351–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price VR, Reed CA, Lieberthal W, Schwartz JH. (2002) ATP depletion of tubular cells causes dissociation of the zonula adherens and nuclear translocation of β-catenin and LEF-1. J Am Soc Nephrol 13:1152–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen K, Murugan S, Vainio S. (2008) Wnt signaling in kidney development and disease. Organogenesis 4:55–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger C, Mandriota S, Jürgensen JS, Wiesener MS, Hörstrup JH, Frei U, Ratcliffe PJ, Maxwell PH, Bachmann S, Eckardt KU. (2002) Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and -2α in hypoxic and ischemic rat kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 13:1721–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. (2007) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Sci STKE 2007:cm8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojadinovic O, Brem H, Vouthounis C, Lee B, Fallon J, Stallcup M, Merchant A, Galiano RD, Tomic-Canic M. (2005) Molecular pathogenesis of chronic wounds: the role of β-catenin and c-myc in the inhibition of epithelialization and wound healing. Am J Pathol 167:59–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton TA, Wilkinson J, Mang HE, Knipe NL, Plotkin Z, Hosein M, Zak K, Wittenborn J, Dagher PC. (2008) p53 regulates renal expression of HIF-1α and pVHL under physiological conditions and after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295:F1666–F1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandara AA, Mustoe TA. (2004) Oxygen in wound healing–more than a nutrient. World J Surg 28:294–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Biju MP, Wang MH, Haase VH, Dong Z. (2006) Cytoprotective effects of hypoxia against cisplatin-induced tubular cell apoptosis: involvement of mitochondrial inhibition and p53 suppression. J Am Soc Nephrol 17:1875–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Reeves WB, Ramesh G. (2009a) Netrin-1 increases proliferation and migration of renal proximal tubular epithelial cells via the UNC5B receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296:F723–F729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Havasi A, Gall J, Bonegio R, Li Z, Mao H, Schwartz JH, Borkan SC. (2010) GSK3β promotes apoptosis after renal ischemic injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 21:284–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Havasi A, Gall JM, Mao H, Schwartz JH, Borkan SC. (2009b) β-Catenin promotes survival of renal epithelial cells by inhibiting Bax. J Am Soc Nephrol 20:1919–1928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidemann A, Bernhardt WM, Klanke B, Daniel C, Buchholz B, Câmpean V, Amann K, Warnecke C, Wiesener MS, Eckardt KU, et al. (2008) HIF activation protects from acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:486–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CC, Lin LC, Wu MS, Chien CT, Lai MK. (2009) Repetitive hypoxic preconditioning attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion induced oxidative injury via up-regulating HIF-1α-dependent bcl-2 signaling. Transplantation 88:1251–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng R, Yao Y, Han M, Zhao X, Liu XC, Wei J, Luo Y, Zhang J, Zhou J, Wang S, et al. (2008) Biliverdin reductase mediates hypoxia-induced EMT via PI3-kinase and Akt. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:380–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Bosch-Marce M, Shimoda LA, Tan YS, Baek JH, Wesley JB, Gonzalez FJ, Semenza GL. (2008) Mitochondrial autophagy is an HIF-1-dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem 283:10892–10903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhuang S, Duan M, Yan Y. (2011) Src family kinases regulate renal epithelial dedifferentiation through activation of EGFR/PI3K signaling. J Cell Physiol http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcp.22946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]