Abstract

The organization and intranuclear localization of nucleic acids and regulatory proteins contribute to both genetic and epigenetic parameters of biological control. Regulatory machinery in the cell nucleus is functionally compartmentalized in microenvironments (focally organized sites where regulatory factors reside) that provide threshold levels of factors required for transcription, replication, repair and cell survival. The common denominator for nuclear organization of regulatory machinery is that each component of control is architecturally configured and every component of control is embedded in architecturally organized networks that provide an infrastructure for integration and transduction of regulatory signals. It is realistic to anticipate emerging mechanisms that account for the organization and assembly of regulatory complexes within the cell nucleus can provide novel options for cancer diagnosis and therapy with maximal specificity, reduced toxicity and minimal off-target complications.

There is growing appreciation that the organization and intranuclear localization of nucleic acids and regulatory proteins contribute significantly to both genetic and epigenetic parameters of biological control. From an historical perspective, there has been a parallel evolution of insight into DNA-encoded regulatory information (genetic control) and control that is epigenetically mediated (regulatory information that is not DNA encoded but conveyed during cell division from parental to progeny cells). Similarly, accrual of insight into architectural organization of regulatory machinery for gene expression and the identification of sequences and factors for genetic and epigenetic parameters of control have generally been independent.

During the past several years there has been a convergence of perspectives, in part technology driven, that provides an integrated concept of gene expression and regulatory mechanisms that are operative within the three dimensional context of nuclear architecture. A blueprint for regulation of gene expression is emerging where combinatorial components of genetic and epigenetic control synergistically contribute to mechanisms that govern biology and pathology.

Effective reviews address the biochemical, molecular and cellular parameters of control 1–5. Here we will focus on an obligatory relationship between mechanisms that mediate genetic and epigenetic components with emphasis on the architectural organization and assembly of regulatory machinery in nuclear microenvironments. While we will confine this mini-review to linkages of nuclear morphology with transcription, the paradigm extends to functional relationships between focally organized regulatory networks in the extracellular matrix and cytoplasm to support the integration of signals required for a broad spectrum of components to biological control. This is an area where Mina Bissell has been instrumental in establishing the conceptual and experimental foundation 6;7.

The Regulatory Landscape of the Cell Nucleus

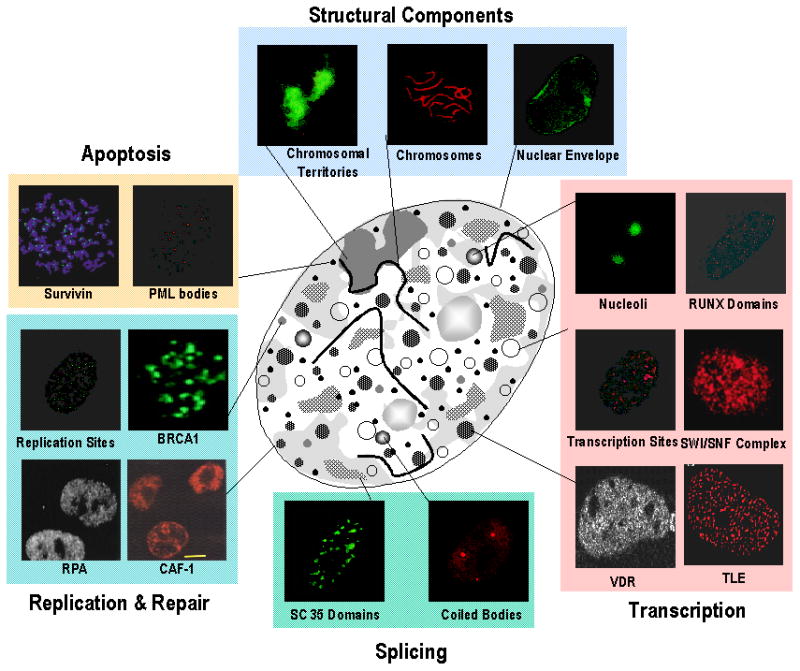

Regulatory machinery within the cell nucleus is functionally organized, assembled and compartmentalized in microenvironments that provide threshold levels of factors required for transcription, replication, repair and cell survival (Figure 1 - - mini-photographs of subnuclear domains). Focusing on gene expression, the transcription factors and cohorts of coregulatory proteins that support combinatorial control of gene activation and suppression, chromatin structure and nucleosome organization as well as physiological responsiveness to a broad spectrum of regulatory cues are architecturally organized and focally configured. This subnuclear compartmentalization establishes specialized domains that can be visualized by microscopy utilizing antibodies for recognition of regulatory proteins and in situ hybridization for detection of genes and transcripts (reviewed in 8–42).

Figure 1.

The nuclear architecture is functionally linked to the organization and sorting of regulatory information. Immunofluorescence microscopy of the proliferating human tumor cells nucleus in situ has revealed the distinct nonoverlapping subnuclear distribution of vital nuclear processes, including: DNA replication sites and proteins involved in replication, such as chromatin assembly factor-1 (CAF-1) and replication protein A (RPA); DNA damage as shown by BRCA1; chromatin remodeling (e.g., mediated by the SWI/SNF complex); structural parameters of the nucleus (e.g., the nuclear envelope, chromosomes and chromosomal territories); RUNX, transducin-like enhancer (TLE) and vitamin D3 receptor (VDR) domains for chromatin organization and transcriptional control of tissue-specific genes; RNA synthesis and processing, involving, for example, transcription sites; SC35 domains, coiled bodies and nucleoli; as well as proteins involved in cell survival (e.g., survivin). Subnuclear promyelocytic leukemia (PML) bodies of unknown function have been examined in numerous cell types 20;26;31;42;58;73–83. All these domains are associated with the nuclear matrix (schematically illustrated in the center). [Reprinted from Stein et al., 200384]

The extent to which architectural organization supports control of transcription is strikingly illustrated at multiple levels of nuclear organization. Transcription factors provide scaffolds that are strategically located at sites on target gene promoters to render sequences accessible to regulatory proteins and determine the extent to which genes are expressed or repressed. The punctate organization of regulatory complexes illustrates the dedication of regions within the nucleus to expression of genes that support proliferation, phenotype and accommodation of requirements for homeostasis. The common denominator for organization of regulatory machinery within the cell nucleus is that each component of control is architecturally configured and every component of control is embedded in architecturally organized networks that provide an infrastructure for integration and transduction of regulatory signals.

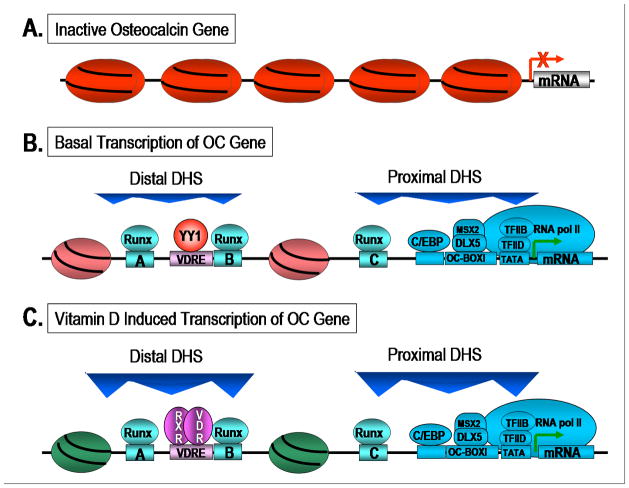

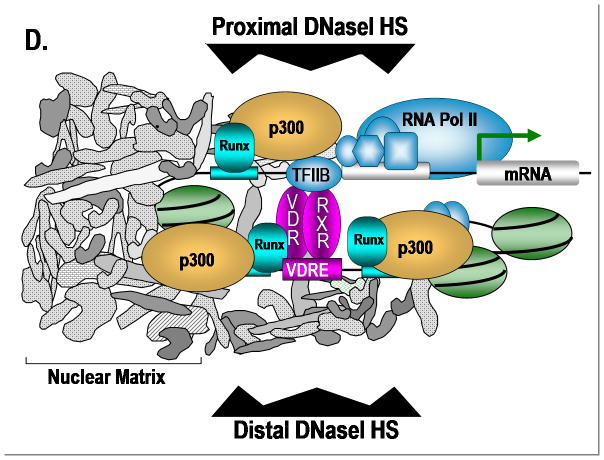

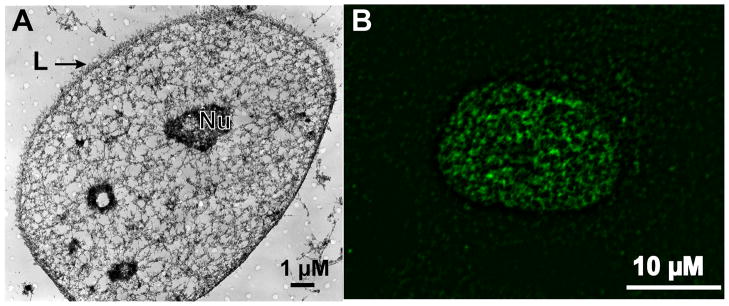

Figure 2 schematically depicts the architectural organization of regulatory proteins on the bone tissue specific osteocalcin gene promoter, where the Runx transcription factor aligns the biochemical components of transcriptional control to establish and sustain competency for expression. Figure 3 shows the punctate organization of Runx regulatory complexes during interphase and mitosis and Figure 4 provides an example of a regulatory network in which the Runx transcription factor supports regulatory cascades from a series of signaling pathways that contribute to biological control. While high resolution microscopy and in situ biochemical techniques have effectively defined the temporal and spatial components of control that are mediated by the architectural organization of transcription regulatory machinery within the cell nucleus, many of the architecturally defined relationships between nuclear structure and function have been validated by in vivo molecular approaches that include genomic and proteomic analyses (e.g., ChiP chromatin immunoprecipitation), ChIP – chip and ChiP – Cseq 43–47.

Figure 2.

Remodeling of the Osteocalcin gene promoter during developmental progression of the osteoblast phenotype. The transcriptionally silent rat osteocalcin gene is schematically illustrated with nucleosomes placed in the proximal tissue-specific and distal enhancer region of the promoter (a). Factors such as Runx and p300 that support basal tissue-specific transcription are recruited to the OC gene promoter and are organized in proximal and distal promoter domains. Modifications in chromatin structure that mediate the assembly of the regulatory machinery for the nuclease hypersensitive sites reflect OC gene transcription. A positioned nucleosome resides between the proximal basal and distal enhancer regions of the promoter (b). In response to vitamin D, chromatin remodeling renders the upstream VDRE competent for binding the VDR/RXR heterodimer with its cognate element (c). Higher order chromatin organization permits crosstalk between basal transcription machinery and the vitamin D receptor complex that involves direct interactions of the vitamin D receptor, Runx 2, p300 and TFIIB (d). [Reprinted from Stein et al., 200385]

Figure 3.

Integration of signal transduction cascades with Runx at subnuclear foci for control of bone formation. The nuclear matrix (NM) filamentous structure visualized by embedment-free electron microscopy 86. The left panel shows an electron micrograph (the cross-link stabilized nuclear matrix of a CaSki cell) with a prominent nuclear matrix scaffold36. The nuclear matrix was uncovered by the method of Nickerson et al.36 and imaged by resinless section electron microscopy, a technique developed by Capco et al. 87. Nu and L designate the nucleolus and nuclear lamina, respectively. The bar in the micrograph is 1 μM. Immunofluorescence microscopy of endogenous Runx2 in ROS 17/2.8 cells showing foci associated with the NM obtained by in situ extraction of soluble chromatin (NM intermediate filament preparation), as described 56;88. The nuclei in the right panel showing Runx2 foci are approximately 10 μM [Reprinted from Lian et al., 200489]

Figure 4.

A Runx regulatory network architecturally integrates signaling pathways that mediate biological control at intranuclear sites.

Intranuclear Trafficking to Regulatory Destinations

Establishing sites within the nucleus that support gene expression necessitates a mechanism to focally localize and functionally compartmentalize regulatory and coregulatory proteins that govern control of transcription. There is a requirement to configure regulatory complexes that can effectively support a diverse series of molecular processes. These components of control encompass but are not confined to rendering sites on target gene promoters accessible for sequence-specific interactions with transcription factors, establishing competency for functional encounters with coregulatory factors. These molecular interactions modulate transcriptional activity within the context of accommodating and executing responses to a broad spectrum of regulatory signals that interface cellular requirements for gene expression with the selective activation and suppression of genes in a manner that is consistent with regulatory signatures for biological control. The extensive array of coregulatory factors that are incorporated into combinatorial regulatory complexes at promoter sites and focally organized in subnuclear domains reflects complexity and dynamic plasticity that can accommodate diverse requirements for biological control.

Several shared features characterize an emerging paradigm for control of gene expression from an architectural perspective. The combinatorial organization and assembly of transcriptional regulatory machinery is architecturally organized to focally support selective activation and repression of genes. The combinatorial regulatory complexes include factors that facilitate interrelationships of architecturally organized regulatory machinery for gene expression with genetic and epigenetic control. Simply stated, the biochemical composition of regulatory machinery supports molecular mechanisms that include: 1) histone modifications, nucleosome structure, and higher order chromatin organization; 2) the biochemical requirements for transcription; and 3) execution of transcriptional programs that are dictated by physiological regulatory cues. The corollary is that biochemical components of the transcriptional regulatory machinery are determinants for architectural organization of regulatory complexes10;48;49. There is an equivalent contribution of architecturally organized regulatory machinery to transcriptional competency and specificity. Architecturally organized regulatory factors are involved in establishing the genomic organization of regulatory complexes. Structure-function interdependency is further illustrated by the genetic and epigenetic parameters of organization for regulatory machinery within the cell nucleus.

The mechanisms responsible for the subnuclear organization of transcriptional regulatory machinery is a fundamental question. The combined application of molecular, cellular, biochemical and in vivo genetic approaches has identified and supported characterization of a 31 amino acid, C terminal intranuclear trafficking sequence that is necessary and sufficient for the punctate organization that is observed for the Runx/AML family of transcription factors. Specificity of the Runx/AML subnuclear trafficking signals is reflected by a unique sequence and crystal structure48–52 Obligatory requirements for fidelity of intranuclear trafficking are supported by linkage with transcriptional competency and capacity to establish the myeloid (Runx1/AML1), bone (Runx2/AML3), and neurological/intestinal (Runx2/AML2) phenotypes in vitro and in vivo 48;49;53–67. There is a similar requirement for fidelity of intranuclear localization to support the transformed phenotype in AML leukemia cells with an 8;21 chromosomal translocation and for breast and prostate cancer cells to form osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions in bone 53;67;68. The requirement for Runx localization within nuclei of tumor cells provides a novel platform for therapy where aberrant intranuclear trafficking sequences can serve as “druggable” targets.

Mitotic Bookmarking: A Novel Architecturally-Mediated Dimension to Epigenetic Control

A key question is whether regulatory complexes are retained during mitosis or are synthesized and reorganized in progeny cells immediately following cell division. Consequently it is essential for epigenetically sustaining the structural and functional integrity of regulatory machinery for tissue specific gene expression.

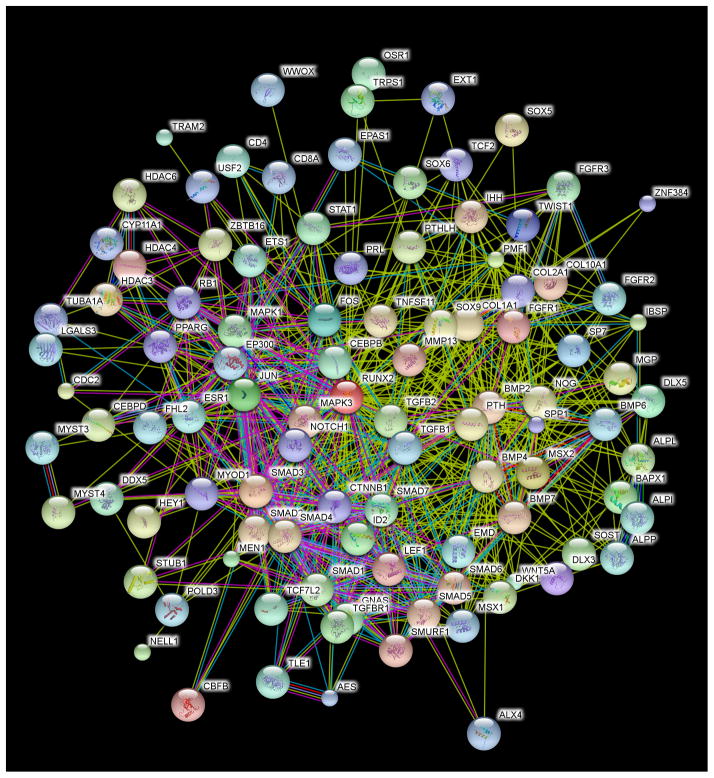

Consistent with the requirement for epigenetically mediated persistence of gene expression, the Runx transcription factors that are master regulators of the bone, myeloid and neurological/gastrointestinal phenotypes have been shown to be: 1) maintained during mitosis as focal regulatory complexes 69; 2) associated with target gene loci on mitotic chromosomes; and 3) retained as focal nuclear microenvironments in post-mitotic progeny cells as sites for the organization and assembly of regulatory machinery for tissue specific gene expression in a manner that reflects the intranuclear organization of RNA polymerase II regulatory machinery during the G2 phase of the cell cycle prior to mitosis 43–45;70–72 (Figure 3).

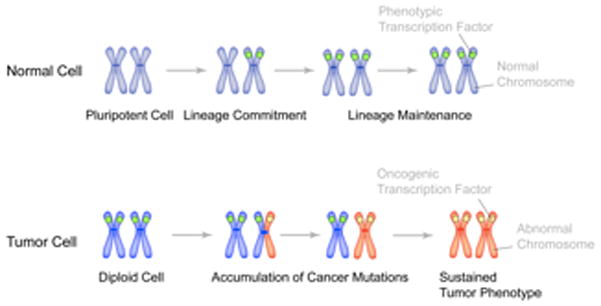

This novel dimension to epigenetic control that supports retention of phenotype competency extends beyond Runx-mediated tissue specific gene expression. Recent results indicate that a similar mitotic retention of transcription regulatory machinery at target gene loci of mitotic chromosomes is operative in myoD and CEBP, illustrating an architectural epigenetic mechanism for sustaining the muscle and adipocyte phenotypes Runx-mediated 70;71. Retention of the AML/ETO transformation–fusion protein at target gene loci of mitotic chromosomes in AML leukemia suggests transcription factor-mediated epigenetic maintenance of the AML/leukemia phenotype 65 (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

Mitotic retention of sequence-specific transcription factors as an epigenetic mechanism for lineage maintenance in normal cells and for the sustained tumor phenotype in cancer cells. Gene loci on metaphase chromosomes (blue color) are occupied by phenotypic transcription factors (green circle) for lineage maintenance through successive cell divisions in normal cells. In tumors, as cells undergo genomic instability and accumulate cancer mutations, it is possible that one allele (shown here as red chromosome arm) is occupied by oncogenic transcription factor (which can be a phenotypic protein, ectopically expressed in cancer cells). Successive cell divisions and acquisition of additional cancer mutations then lead to the replacement of phenotypic regulatory proteins with oncogenic transcription factors. Occupancy of target gene loci with oncogenic proteins results in sustained tumor phenotype. [Reprinted from Stein et al., 201090]

Recognizing that all transcription factors are not retained on target genes during mitosis72 suggests that transcription factor-mediated epigenetic control is selective and that additional regulatory mechanisms contribute to retention of cell fate and lineage commitment during proliferation. It is also necessary to extend understanding of the extent to which coregulatory factors, both co-activators and co-repressors, are retained as mitotic complexes. While the initial indication is that while mitotic persistence of coregulatory factors occurs, the extent to which this component of control is operative remains to be determined 70;71. However, there is growing support for epigenetic retention of lineage committed transcription factors for control of genes transcribed by RNA polymerase II as well as by RNA polymerase I (ribosomal genes), providing a mechanistic basis for coordinating control of cell growth and phenotype 43;45.

Architecturally-Mediated Facilitation of Biological Control

Accruing evidence is solidifying acceptance that the architectural organization of regulatory machinery for genetic and epigenetic control of gene expression is a principal parameter of biological control. The focal organization of combinatorial components for transcriptional regulation in nuclear microenvironments provides support for a catalytic role of nuclear architecture in establishing and sustaining threshold concentrations that effectively support physiologically responsive activity. The engagement of cellular architecture in the sorting and trafficking of regulatory macromolecules, a concept pioneered by Mina Bissell and her colleagues, is viewed as an important component of regulation in many biological contexts. Perturbations in architecturally mediated regulation have been implicated in gene expression that is associated with the onset and progression of diseases that include cancer. Modifications in the intranuclear organization of regulatory machinery in cancer cells that are linked to perturbed transcription factor localization provide tumor restricted druggable targets. It is realistic to anticipate that emerging mechanisms that account for the organization and assembly of regulatory complexes within the cell nucleus can provide novel options for cancer diagnosis and therapy with maximal specificity, reduced toxicity and minimal off-target complications.

Acknowledgments

The authors are appreciative of the editorial assistance from Patricia Jamieson with the preparation of this manuscript. Studies described in this review are supported by NIH grants: 5P01 CA082834, 5P01 AR048818, and 1RC1 AG035886-01. Gary Stein and Jane Lian are members of the UMass DERC (DK32520).

Reference List

- 1.Weake VM, Workman JL. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:426–437. doi: 10.1038/nrg2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roeder RA, Schulman CI. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:971–975. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181e1e802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sumitomo A, Ishino R, Urahama N, Inoue K, Yonezawa K, Hasegawa N, Horie O, Matsuoka H, Kondo T, Roeder RG, Ito M. Mol Cell Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01348-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Alessio JA, Wright KJ, Tjian R. Mol Cell. 2009;36:924–931. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darzacq X, Yao J, Larson DR, Causse SZ, Bosanac L, de T, Ruda VVM, Lionnet T, Zenklusen D, Guglielmi B, Tjian R, Singer RH. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:173–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nam JM, Onodera Y, Bissell MJ, Park CC. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5238–5248. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spencer VA, Xu R, Bissell MJ. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith KP, Luong MX, Stein GS. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:21–29. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaidi SK, Young DW, Montecino M, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4758–4766. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00646-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaidi SK, Young DW, Montecino M, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:583–589. doi: 10.1038/nrg2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein GS, van Wijnen AJ, Imbalzano AN, Montecino M, Zaidi SK, Lian JB, Nickerson JA, Stein JL. Crit Rev Eukaryotic Gene Exp. 2010 doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v20.i2.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein GS, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Javed A, Montecino M, Zaidi SK, Young D, Choi JY, Gutierrez S, Pockwinse S. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:287–302. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaidi SK, Young DW, Javed A, Pratap J, Montecino M, van Wijnen A, Lian JB, Stein JL, Stein GS. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:454–463. doi: 10.1038/nrc2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roix JJ, McQueen PG, Munson PJ, Parada LA, Misteli T. Nat Genet. 2003;34:287–291. doi: 10.1038/ng1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cremer T, Cremer M, Dietzel S, Muller S, Solovei I, Fakan S. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gauwerky CE, Croce CM. Semin Cancer Biol. 1993;4:333–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konety BR, Getzenberg RH. J Cell Biochem. 1999;(Suppl 32–33):183–191. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(1999)75:32+<183::aid-jcb22>3.3.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein GS, Montecino M, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB. Cancer Research. 2000;60:2067–2076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parada L, Misteli T. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:425–432. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeFranco DB. Molecular Endocrinology. 2002;16:1449–1455. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.7.0880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spector DL. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114:2891–2893. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.16.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosak ST, Groudine M. Science. 2004;306:644–647. doi: 10.1126/science.1103864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taatjes DJ, Marr MT, Tjian R. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:403–410. doi: 10.1038/nrm1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Handwerger KE, Gall JG. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer AH, Bardarov S, Jr, Jiang Z. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:170–184. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonhardt H, Rahn HP, Cardoso MC. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1998;30–31:243–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonhardt H, Cardoso MC. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2000;(Suppl 35):78–83. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(2000)79:35+<78::aid-jcb1129>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isogai Y, Tjian R. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:296–303. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaidi SK, Young DW, Choi JY, Pratap J, Javed A, Montecino M, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein GS. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:128–133. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coffey DS, Getzenberg RH, DeWeese TL. JAMA. 2006;296:445–448. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Htun H, Barsony J, Renyi I, Gould DL, Hager GL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4845–4850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delcuve GP, Rastegar M, Davie JR. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:243–250. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein GS, Davie JR, Knowlton JR, Zaidi SK. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:1949–1952. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delcuve GP, He S, Davie JR. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan KM, Nickerson JA, Krockmalnic G, Penman S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:933–938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nickerson JA, Krockmalnic G, Wan KM, Penman S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4446–4450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leman ES, Getzenberg RH. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:1988–1993. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeitz MJ, Malyavantham KS, Seifert B, Berezney R. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:125–133. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malyavantham KS, Bhattacharya S, Barbeitos M, Mukherjee L, Xu J, Fackelmayer FO, Berezney R. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:391–403. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dimitrova DS, Berezney R. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4037–4051. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pliss A, Koberna K, Vecerova J, Malinsky J, Masata M, Fialova M, Raska I, Berezney R. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:554–565. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei X, Samarabandu J, Devdhar RS, Siegel AJ, Acharya R, Berezney R. Science. 1998;281:1502–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young DW, Hassan MQ, Yang XQ, Galindo M, Javed A, Zaidi SK, Furcinitti P, Lapointe D, Montecino M, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3189–3194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611419104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohta S, Bukowski-Wills JC, Sanchez-Pulido L, Alves FL, Wood L, Chen ZA, Platani M, Fischer L, Hudson DF, Ponting CP, Fukagawa T, Earnshaw WC, Rappsilber J. Cell. 2010;142:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young DW, Hassan MQ, Pratap J, Galindo M, Zaidi SK, Lee SH, Yang X, Xie R, Javed A, Underwood JM, Furcinitti P, Imbalzano AN, Penman S, Nickerson JA, Montecino MA, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Nature. 2007;445:442–446. doi: 10.1038/nature05473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young DW, Zaidi SK, Furcinitti PS, Javed A, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117:4889–4896. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young DW, Pratap J, Javed A, Weiner B, Ohkawa Y, van WA, Montecino M, Stein GS, Stein JL, Imbalzano AN, Lian JB. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:720–730. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng C, McNeil S, Pockwinse S, Nickerson JA, Shopland L, Lawrence JB, Penman S, Hiebert SW, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1585–1589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeng C, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Meyers S, Sun W, Shopland L, Lawrence JB, Penman S, Lian JB, Stein GS, Hiebert SW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6746–6751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stein GS. J Cell Biochem. 1998;70:157–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang L, Guo B, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein JL, Stein GS, Zhou GW. J Struct Biol. 1998;123:83–85. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang L, Guo B, Javed A, Choi JY, Hiebert S, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Zhou GW. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33580–33586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McNeil S, Zeng C, Harrington KS, Hiebert S, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14882–14887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gordon JA, Pockwinse SM, Stewart FM, Quesenberry PJ, Nakamura T, Croce CM, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. J Cell Biochem. 2000;77:30–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi JY, Pratap J, Javed A, Zaidi SK, Xing L, Balint E, Dalamangas S, Boyce B, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein JL, Jones SN, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8650–8655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151236498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zaidi SK, Javed A, Choi JY, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114:3093–3102. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.17.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaidi SK, Sullivan AJ, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8048–8053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112664499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harrington KS, Javed A, Drissi H, McNeil S, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Wang YL, Stein GS. Journal of Cell Science. 2002;115:4167–4176. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barnes GL, Hebert KE, Kamal M, Javed A, Einhorn TA, Lian JB, Stein GS, Gerstenfeld LC. Cancer Research. 2004;64:4506–4513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Javed A, Afzal F, Zaidi SK, Young D, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. ICCBMT, Banff Alberta, Canada Proceedings. :200417–22. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vradii D, Zaidi SK, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7174–7179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502130102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zaidi SK, Javed A, Pratap J, Schroeder TM, Westendorf J, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS, Stein JL. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:935–942. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zaidi SK, Pande S, Pratap J, Gaur T, Grigoriu S, Ali SA, Stein JL, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19861–19866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709650104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Javed A, Bae JS, Afzal F, Gutierrez S, Pratap J, Zaidi SK, Lou Y, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8412–8422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705578200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bakshi R, Zaidi SK, Pande S, Hassan MQ, Young DW, Montecino M, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS. Journal of Cell Science. 2008;21:3981–3990. doi: 10.1242/jcs.033431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pande S, Ali SA, Dowdy C, Zaidi SK, Ito K, Ito Y, Montecino MA, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:473–479. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zaidi SK, Dowdy CR, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Raza A, Stein JL, Croce CM, Stein GS. Cancer Research. 2009;69:8249–8255. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Javed A, Barnes GL, Pratap J, Antkowiak T, Gerstenfeld LC, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1454–1459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409121102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zaidi SK, Young DW, Pockwinse SH, Javed A, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14852–14857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2533076100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ali SA, Zaidi SK, Dacwag CS, Salma N, Young DW, Shakoori AR, Montecino MA, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Imbalzano AN, Stein GS, Stein JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6632–6637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800970105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ali SA, Zaidi SK, Dobson JR, Shakoori AR, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4165–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000620107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bakshi R, Hassan MQ, Pratap J, Lian JB, Montecino MA, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Imbalzano AN, Stein GS. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:569–576. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Misteli T. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;113:1841–1849. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.11.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cook PR. Science. 1999;284:1790–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stenoien DL, Simeoni S, Sharp ZD, Mancini MA. J Cell Biochem. 2000;(Suppl 35):99–106. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(2000)79:35+<99::aid-jcb1132>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith KP, Moen PT, Wydner KL, Coleman JR, Lawrence JB. Journal of Cell Biology. 1999;144:617–629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Merriman HL, van Wijnen AJ, Hiebert S, Bidwell JP, Fey E, Lian J, Stein J, Stein GS. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13125–13132. doi: 10.1021/bi00040a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Javed A, Guo B, Hiebert S, Choi JY, Green J, Zhao SC, Osborne MA, Stifani S, Stein JL, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;113:2221–2231. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Difilippantonio MJ, Petersen S, Chen HT, Johnson R, Jasin M, Kanaar R, Ried T, Nussenzweig A. J Exp Med. 2002;196:469–480. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guo B, Odgren PR, van Wijnen AJ, Last TJ, Nickerson J, Penman S, Lian JB, Stein JL, Stein GS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10526–10530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kimura H, Tao Y, Roeder RG, Cook PR. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5383–5392. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Verschure PJ, van Der Kraan I, Manders EM, van Driel R. Journal of Cell Biology. 1999;147:13–24. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dyck JA, Maul GG, Miller WH, Chen JD, Kakizuka A, Evans RM. Cell. 1994;76:333–343. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stein GS, Zaidi SK, Braastad CD, Montecino M, van Wijnen AJ, Choi JY, Stein JL, Lian JB, Javed A. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:584–592. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stein GS, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Montecino M, Javed A, Zaidi SK, Young DW, Choi JY, Pockwinse SM. Oncogene. 2004;23:4315–4329. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Capco DG, Wan KM, Penman S. Cell. 1982;29:847–858. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Capco DG, Krochmalnic G, Penman S. Journal of Cell Biology. 1984;98:1878–1885. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.5.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prince M, Banerjee C, Javed A, Green J, Lian JB, Stein GS, Bodine PV, Komm BS. J Cell Biochem. 2001;80:424–440. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20010301)80:3<424::aid-jcb160>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lian JB, Javed A, Zaidi SK, Lengner C, Montecino M, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2004;14:1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stein GS, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Montecino M, Croce CM, Choi JY, Ali SA, Pande S, Hassan MQ, Zaidi SK, Young DW. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2010;50:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]