Abstract

Coccidioidomycosis typically presents as pneumonia, but rarely manifests as extrapulmonary disease. We describe a case of coccidioidal infection that presented as a neck mass and was diagnosed by fine needle aspiration (FNA). Initial clinical suspicion was for mycobacterial infection. Several modalities are available for the detection of Coccidioides species, but culture has been the mainstay of diagnosis. FNA provides a relatively noninvasive and effective modality for tissue-based diagnosis based on characteristic histological findings. It allows the additional advantage of early on-site identification, allowing for triage of the specimen, notification of laboratory staff and prompt initiation of treatment. The case herein described is intended to demonstrate an atypical presentation of extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis and highlight the utility of FNA for diagnosis of such lesions. Clinicians should be aware of the unique advantages of FNA for evaluation of lesions of infectious etiology.

Keywords: Coccidioides, Fine needle aspiration, Extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis

The Coccidioides fungus is thermally dimorphic and endemic to the southwestern United States and regions of Mexico, Central America, and South America. Infections with Coccidioides are typically contracted through inhalation of arthroconidial spores. In endemic areas, many infections may be asymptomatic or self-limited. The most common presentation for symptomatic illness is pneumonia, but extrapulmonary manifestations may occur through lymphatic drainage and hematogenous spread in less than 5% of cases.1 Both immunosuppression and race are predictors of dissemination, with persons of African American and Filipino descent being at highest risk. The most common sites of extrapulmonary dissemination are skin, soft tissue, the central nervous system, and bone.2

Diagnosis may be made through a combination of tissue analysis, microbiology culture, and serum antibody detection. Two morphologically indistinct species of Coccidioides are responsible for human infections: Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii.3 Speciation is not usually completed, since clinical presentation and treatment for the two is identical. Serologic antibody detection tests for Coccidioides are usually immunodiffusion or complement fixation- based, but they carry the disadvantage of being labor intensive and sometimes lacking sensitivity, particularly in the early stages of infection.4–6 Skin antigen testing is becoming available, but will remain positive in the case of asymptomatic or remote infections.7,8 Additionally, patients with extensive disease may be anergic. A blood and urine antigen test has been developed and was found to have a sensitivity of approximately 50% to 70%.9,10 Definitive culture from a clinical specimen remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

Case Presentation

A Mexican man, aged 38 years, with a history of Type II diabetes mellitus presented with a four-month history of a right-sided neck mass. The mass developed quickly, but then remained stable in size. It was tender and non-mobile with an erythematous, scaly surface. Three months after the mass was first noted, the patient developed cough, fevers, and night sweats. The patient had immigrated to the United States from Puebla, Mexico one year before and worked as a welder. He had traveled home to Mexico shortly before the development of the neck mass, and upon his return had been treated with a one-week course of moxifloxacin for a suspected case of community-acquired pneumonia. Physical exam revealed a right cervical supraclavicular fossa mass that was tender, erythematous, and fluctuant (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Physical examination of the patient revealed a firm, fixed erythematous mass in the right cervical supraclavicular region.

Laboratory tests upon admission did not demonstrate leukocytosis (white blood cell count was 9.8 K/μL) or any electrolyte abnormalities. A chest radiograph showed a prominent, ill-defined mass configuration in the right medial supraclavicular region, corresponding to the clinically presenting mass. There were ill-defined patchy opacities in the right lower lobe, but the left lung was clear.

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck showed a multiloculated, rim-enhancing, necrotic mass in the right lower neck, measuring 4.4 cm x 0.9 cm and involving the right level III, IV, V, and supraclavicular regions (figure 2). Lymphadenopathy was noted in the right level II and III regions, as well as necrotic lymphadenopathy in the mediastinum. Subsequent chest CT demonstrated numerous nodular opacities throughout both lungs with focal consolidation and air bronchograms present in the right lower lobe.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography images show necrotic tissue corresponding to the neck mass

Based on the patient’s presentation and CT findings, primary tuberculosis infection was felt to be the most likely cause, but other causes such as mycobacteria, fungi, sarcoidosis, and malignancy were also considered in the differential diagnosis.

Serum antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus 1 and 2 were negative, as was a QuantiFERON-TB Gold test (Quest Diagnostics, Madison, NJ). After fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the mass, Papanicolaou-stained slides demonstrated numerous spherules ranging in size from 30 μm to 70 μm, some of which contained endospores. In some areas, ruptured spherules releasing endospores were visible, giving the classic “crushed ping pong ball” appearance (figure 3). Diff-Quik-stained slides demonstrated spherules of varying sizes with less definition. Cultures of the fluid were sent to the microbiology laboratory and grew hyphae with arthroconidia, consistent with Coccidioides spp (figure 4). Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex polymerase chain reaction performed on the aspirate was negative, and a Gram stain showed no organisms.

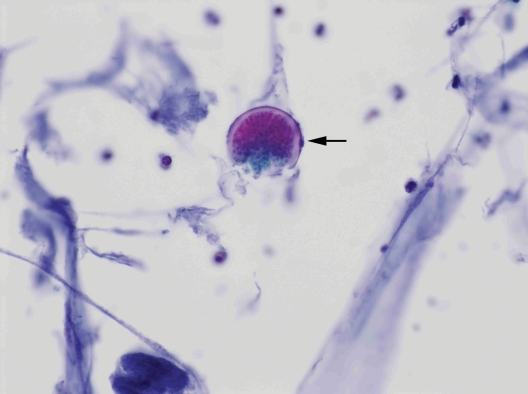

Figure 3.

Fine needle aspiration slides demonstrate spherules with refractile walls (arrow), some releasing endospores (Papanicolaou stain, ×400)

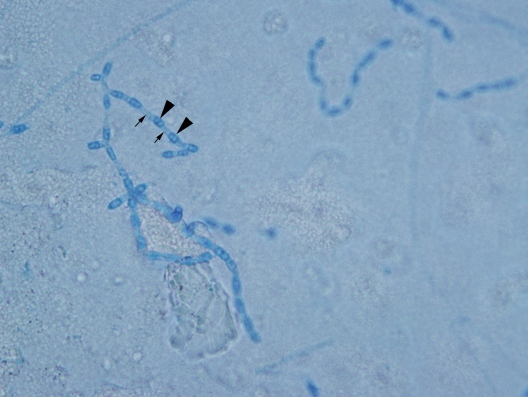

Figure 4.

Lactophenol cotton blue wet mount preparation from microbiology sample showing barrel-shaped alternate arthroconidia. Arrowheads indicate the arthroconidia, which are the easily aerosolized infectious particles. Small arrows point to the disjunctor cells.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis for an isolated neck mass is extensive. Since this patient’s presentation was relatively rare for Coccidioides, the initial clinical suspicion was higher for a mycobacterial infection. Serum antibodies for Coccidioides were not sent because the patient originated from the Puebla region of Mexico which has a subtropical highland climate and is not within the currently-identified endemic range for coccidioidomycosis.11 Other infectious etiologies were considered however, as well as granulomatous processes including sarcoidosis. Malignancies such as carcinoma metastatic to lymph node or cutaneous lymphoma were also considered in the differential diagnosis.

Typically such a presentation requires tissue examination; however, avoidance of an excisional biopsy in this setting is desirable. Successfully used for many decades throughout the United States, FNA is a routine diagnostic procedure12–16 that can be done in a clinic setting, is rapid, and can be performed with only local anesthesia, or even without anesthesia.16 It offers powerful advantages in that it is a minimally-invasive technique with low morbidity and can access both superficial and deep-seated lesions. A typical FNA results in a tissue specimen adequate for a multitude of diagnostic modalities including microbiologic culture, flow cytometric analysis, and molecular studies.

Fine needle aspiration has proven to be an effective tool in the diagnosis of infectious lesions, including fungal infections.17 The stains typically used for FNA slides are Papanicolaou and Romanowsky (Diff-Quik), which optimize visualization of nuclear and cytoplasmic detail, respectively. Both are acceptable for identification of fungal and yeast forms. In addition, a granulomatous reaction may be identified in the cells surrounding the organisms. Previous work examining the utility of FNA for pulmonary Coccidioides suggests that it is highly effective and specific.18 A study by Raab et al19 examining 73 cases of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis described characteristic FNA findings including granular acellular debris and intact and ruptured spherules. Granulomatous inflammation was not always evident, and mycelial forms were only present in four cases. In all the cases described, FNA findings were sufficient for definitive diagnosis and surgical intervention for tissue was not required.

There are no large systematic studies that examine the utility of FNA for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Two prior case reports indicate that this is possible.20,21 Our report confirms and emphasizes the advantages of FNA that are not available with other tissue sampling methods. The greatest benefit of FNA in such cases may be on-site evaluation, which is a useful first step in identifying thermally dimorphic fungi. It is important for physicians performing on-site evaluation of potentially infectious FNA’s to recognize characteristic morphology of Coccidioides species and be vigilant in cases of granulomatous inflammation, since early identification of these organisms can expedite treatment initiation. If spherules and endospores are recognized at the on-site evaluation, diagnosis may precede fungal cultures by several days. Additionally, since these organisms are highly infectious, notification of laboratory personnel is essential to maintain their safety.22 Coccidioides species are classified as select agents by the Centers for Disease Control, meaning that they must be destroyed or sent to an appropriate facility for secure handling.

In summary, Coccidioides infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a neck mass. A careful travel history may identify travel to or habitation in endemic areas, or it may be confounding, as in this case. Clinicians should be aware that FNA is an effective tool for diagnosis of extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis and can streamline the diagnostic process allowing for early initiation of antifungal treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kurt Reed, MD, MGIS for his assistance in consultation and for providing images from microbiology samples.

References

- 1.Parish JM, Blair JE. Coccidioidomycosis. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiller TM, Galgiani JN, Stevens DA. Coccidioidomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2003;17:41–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher MC, Koenig GL, White TJ, Taylor JW. Molecular and phenotypic description of Coccidioides posadasii sp. nov., previously recognized as the non-California population of Coccidioides immitis. Mycologia 2002;94:73–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pappagianis D, Zimmer BL. Serology of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 1990;3:247–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair JE, Coakley B, Santelli AC, Hentz JG, Wengenack NL. Serologic testing for symptomatic coccidioidomycosis in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts. Mycopathologica 2006;162:317–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang MC, Magee DM, Cox RA. Mapping of a Coccidioides immitis-specific epitope that reacts with complement-fixing antibody. Infect Immun 1997;65:4068–4074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens DA, Levine HB, TenEyck DR. Dermal sensitivity to different doses of spherulin and coccidioidin. Chest 1974;65:530–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ampel NM, Hector RF, Lindan CP, Rutherford GW. An archived lot of coccidioidin induces specific coccidioidal delayed-type hypersensitivity and correlates with in vitro assays of coccidioidal cellular immune response. Mycopathologica 2006;161:67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durkin M, Connolly P, Kuberski T, Myers R, Kubak BM, Bruckner D, Pegues D, Wheat LJ. Diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis with use of the Coccidioides antigen enzyme immunoassay. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durkin M, Estok L, Hospenthal D, Crum-Cianflone N, Swatzenruber S, Hackett E, Wheat LJ. Detection of Coccidioides antigenemia following dissociation of immune complexes. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2009;16:1453–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laniado-Labor’n R. Coccidioidomycosis and other endemic mycoses in Mexico. Rv Iberoam Micol 2007;24:249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong DS, Li GK. The role of fine-needle aspiration cytology in the management of parotid tumors: a critical clinical appraisal. Head Neck 2000;22:469–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes JH, Cohen MB. Fine-needle aspiration of the pancreas. Pathology 1996;4:389–407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Khafaji BM, Nestok BR, Katz RL. Fine-needle aspiration of 154 parotid masses with histologic correlation: ten-year experience at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Cancer 1998;84:153–159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Florentine BD, Staymates B, Rabadi M, Barstis J, Black A; Cancer Committee of the Henry Mayo Newhall Memorial Hospital The reliability of fine-needle aspiration biopsy as the initial diagnostic procedure for palpable masses: a 4-year experience of 730 patients from a community hospital-based outpatient aspiration biopsy clinic. Cancer 2006; 107:406–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frates MC, Benson CB, Charboneau JW, Cibas ES, Clark OH, Coleman BG, Cronan JJ, Doubilet PM, Evans DB, Goellner JR, Hay ID, Hertzberg BS, Intenzo CM, Jeffrey RB, Langer JE, Larsen PR, Mandel SJ, Middleton WD, Reading CC, Sherman SI, Tessler FN; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Management of thyroid nodules detected at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound consensus conference statement. Radiology 2005;237:794–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atkins KA, Powers CN. The cytopathology of infectious diseases. Adv Anat Pathol 2002;9:52–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eloubeidi MA, Tamhane A, Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM. Frequency of major complications after EUS-guided FNA of solid pancreatic masses: a prospective evaluation. Gastrointest Endosc 2006;63:622–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raab SS, Silverman JF, Zimmerman KG. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Spectrum of cytologic findings in 73 patients. Am J Clin Pathol 1993;99:582–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hicks MJ, Green LK, Clarridge J. Primary diagnosis of disseminated coccidioidomycosis by fine needle aspiration of a neck mass. A case report. Acta Cytol 1994;38:422–426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold MG, Arnold JC, Bloom DC, Brewster DF, Thiringer JK. Head and neck manifestations of disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Laryngoscope 2004;114:747–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens DA, Clemons KV, Levine HB, Pappagianis D, Baron EJ, Hamilton JR, Deresinski SC, Johnson N. Expert opinion: what to do when there is Coccidioides exposure in a laboratory. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:919–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]