Abstract

Anticipatory grief is the process of experiencing normal phases of bereavement in advance of the loss of a significant person. To date, anticipatory grief has been examined in family caregivers to individuals who have had Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) an average of 3 to 6 years. Whether such grief is manifested early in the disease trajectory (at diagnosis) is unknown. Using a cross-sectional design, we examined differences in the nature and extent of anticipatory grief between family caregivers of persons with a new diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI, n=43) or AD (n=30). We also determined whether anticipatory grief levels were associated with caregiver demographics, caregiving burden, depressive symptoms and marital quality. Mean anticipatory grief levels were high in the total sample, with AD caregivers endorsing significantly more anticipatory grief than MCI caregivers. In general, AD caregivers endorsed difficulty functioning whereas MCI caregivers focused on themes of “missing the person” they once knew. Being a female caregiver, reporting higher levels of objective caregiving burden and higher depression levels each bore independent, statistically significant relationships with anticipatory grief. Given these findings, family caregivers of individuals with mild cognitive deficits or a new AD diagnosis may benefit from interventions specifically addressing anticipatory grief.

Keywords: Anticipatory grief, dementia caregiving, mild cognitive impairment

Anticipatory grief (AG) refers to the process of experiencing the phases of normal bereavement in advance of the loss of a significant person.1,2 It encompasses the mourning, coping, planning, and psychosocial reorganization that are stimulated and begun, in part, in response to the awareness of an impending loss (usually death) and in the recognition of associated losses in the past, present, and future.3 In the context of dementia family caregiving, anticipatory grieving may extend over many years while family members witness deterioration in the affected person’s cognitive, social, and physical functioning.1 Family caregivers also face changes in their roles and level of personal freedom while they contemplate the care recipient’s inevitable incapacitation.4

In the past, grief was understood primarily in the context of post-death emotion or bereavement. The anticipatory grief experienced by family dementia caregivers was subsumed under the rubrics of caregiver depression, strain, and/or burden.5 Over the past twenty years qualitative and descriptive studies have suggested that anticipatory grief among caregivers can negatively influence their mood, physical health, productivity, and social relationships.6-11 Studies also suggest that anticipatory grief also affects post-death bereavement and grief resolution.12-15 Therefore, considering anticipatory grief in conceptual models of caregiving burden may help to clarify the manner by which various stressors in the dementia caregiving situation uniquely influence individual caregiver outcomes.

The focus on grief in family caregivers has challenged the stress-burden paradigm by conceptualizing grief as a critical component of the dementia caregiving experience that may adversely impact a caregivers’ physical and mental health (distress).16 The addition of this component to the new paradigm has the potential to enhance our understanding of what family members experience over the caregiving role trajectory. It is also possible that anticipatory grief, if expressed openly, can relieve some of the burden or distress (e.g., depression) associated with the dementia caregiving role.

To date, however, investigators have examined anticipatory grief levels only after AD caregivers have experienced the burden of providing care for many years, well past the time in which the disease was diagnosed or symptoms were first evident (an average of 3 to 6 years since diagnosis).4, 7-9 Whether or not symptoms of anticipatory grief begin at the time of their family member’s disease diagnosis or at the initial identification of cognitive symptoms is not known. In particular, diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment (MCI, a potential precursor of AD) are becoming more frequent and it is important to establish if anticipatory grief is also observed - and to the same degree - in family caregivers of persons with mild cognitive deficits (not yet meeting criteria for a diagnosis of dementia) or soon after a diagnosis of AD. Since studies suggest that each stage of dementia caregiving may have a distinct set of anticipatory grief reactions in family caregivers17-19 it is possible that family caregivers of persons with MCI express different levels and types of anticipatory grief reactions than do family caregivers of persons with AD. Along similar lines, if anticipatory grief does occur at the time of AD diagnosis, or earlier, what aspects of the caregiver or the caregiving experience are associated with anticipatory grief in these relatively new family caregivers? Identification of anticipatory grief, even at these very early stages of the caregiving trajectory, could pave the way for the development of strategies to better support caregiver well-being to maximize their ability to aide their family member as this individual’s health status declines.

In the current study, we set out to characterize the nature and level of anticipatory grief among a sample of relatively new caregivers residing with a family member recently diagnosed with either MCI or AD. An additional goal was to determine if anticipatory grief was correlated with caregiver sociodemographic characteristics, caregiver burden, depression, or marital quality (among spousal caregivers) in our sample. These factors were selected because they have been found to predict other health and well-being outcomes in family dementia caregivers.20-23

METHODS

Participants

Subjects in the present investigation were enrolled in a larger study testing an intervention designed to prevent depression in family caregivers to individuals with cognitive impairment. Data reported here were collected prior to any intervention (see Procedures Section below). Subjects were recruited from the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) patient and family caregiver registry. Eligible participants were the primary family caregiver (spouses, adult children, significant others) of individuals with a new University of Pittsburgh ADRC consensus diagnosis of MCI or AD. An ADRC diagnosis of MCI required objectively verified cognitive deficits in memory or up to two other cognitive domains (e.g., aphasia, apraxia, agnosia) with otherwise normal cognitive function.24 The criteria define the cognitive deficits as scores 1.5 standard deviation units below that of individuals of comparable age and education without sufficiently severe cognitive impairment or loss of daily living skills to constitute dementia.

The family caregiver to each patient was identified by the ADRC study coordinator as the person most likely to provide care and assistance to the affected person if needed, and this role was verified with potential subjects when they were approached for study participation. To be eligible for the current study, the participants had to live with their cognitively impaired family member in a community (non-institutional and non-assisted) setting within a 300 mile radius from the study site, and be able to understand English.

Over a 46-month time frame, 203 persons were newly diagnosed with MCI or AD at the ADRC. Twenty-nine (14.2%) of these individuals did not have a family caregiver, and caregivers to 28 (13.7%) additional patients did not meet study eligibility criteria (22 lived more than 300 miles away, and 6 caregivers no longer lived with the patients in a non-institutional setting). Further, 12 (5.9%) patients or their family caregivers requested that they not be approached for caregiver studies. This resulted in a pool of 134 (66%) eligible caregivers, of whom 61 (45%) declined participation (47 citing either lack of interest or time for participation in a multi-session intervention study, 7 stating that their own health status precluded participation, and 7 citing distress over their family member’s new diagnosis). Thus, 73 family caregivers were enrolled. The final sample consisted of 43 (59%) MCI family caregivers and 30 (41%) AD family caregivers.

Procedure

During the regularly scheduled meeting to discuss outcomes of the ADRC diagnostic evaluation, the ADRC study coordinator asked if the family caregiver would be interested in participating in the larger study testing an intervention to keep family members healthy in the face of any caregiving responsibilities. If they were interested in participating, informed consent was obtained and data described in the present report were gathered by a trained research associate during a single interview in the respondent’s home. Additional information regarding the cognitively impaired family member’s status at the time of diagnosis was gathered from the ADRC medical records, after informed consent from the ADRC patient or their proxy was obtained.

Measures

Caregiver demographic information (age, gender, race, level of education, employment status, income, type of relationship to the patient, years in the relationship, number of cohabitants in household, number of disabling illnesses) was gathered, along with measures of anticipatory grief, objective caregiver burden, marital quality, and depression.

Anticipatory Grief

The Anticipatory Grief Scale1 (AGS) is composed of 27 grief-related items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The possible range of AGS scores is 27-135; higher scores indicate higher levels of anticipatory grief. The AGS was developed and originally validated in dementia caregivers. In the current sample, internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’sα) of the AGS was .84.

Objective Caregiver Burden

Three measures considered elements of the objective burden associated with the caregiving role.

Responsibilities

Caregivers indicated which of 8 activities of daily living (ADL) tasks (e.g., help with feeding, bathing, dressing, walking, toileting, transferring ) and 11 instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) tasks (e.g., medication management, preparing meals, running errands, money management) they had newly assumed responsibility for since their family member began developing “memory problems.” These ADL and IADL items were adapted from the task burden list of Montgomery and associates.25 The total number of new ADL responsibilities were summed, as was the total number of new IADL responsibilities.

Lifestyle Constraints

Montgomery’s Objective Caregiver Burden Scale25 (OBS) was used to determine perceptions of lifestyle constraint related to caregiving responsibilities (e.g., time, privacy, money, and leisure activities). Respondents rated eight items concerning the degree to which aspects of their life were affected by their family member’s memory impairment (1 = little or no restriction; 5 = a large degree of restriction). The OBS demonstrated high internal consistency reliability with the current sample (α = .84).

Behavioral Stressors

Respondents reported on the frequency of 30 possible behavioral problems exhibited by their family members using the Memory and Behavior Problem Checklist26 (MBPC). The MBPC items encompass behavioral problems commonly exhibited by individuals with dementia. Each behavior is rated on a 6-point scale (0 = never occurred to 5 = occurs daily or more often). The number of problematic behaviors that occurred weekly or more often was tallied.

Marital Quality

The quality of the marital relationship was evaluated using the Dyadic Adjustment Scale27 (DAS). The DAS is a 32-item self-report measure of marital quality that yields a summary score ranging from 0 (low marital quality) to 151 (high marital quality). Cronbach’s alpha in the subsample of spousal caregivers was .89 for the DAS.

Depression

Depressive symptoms were measured with Center for Epidemiological Studies the – Depression Scale28 (CES-D). The CES-D is designed to measure depressive symptoms in non-psychiatric subjects and it has predictive validity for the diagnosis of depression in family caregiving samples.29-31 Its 20 items are each rated in terms of symptoms frequency in the preceding week (0 = rarely or less than one day last week and 3 = most of the time or 5-7 days last week). A higher total CES-D score indicates a higher level of depressive symptoms. The reliability alpha for the CES-D is .86 in the current sample.

Analysis

Independent sample t-tests and chi-square analyses were conducted to compare the two groups of caregivers (MCI vs. AD) on demographic characteristics, total AGS score, as well as other study measures (caregiving burden indices, marital quality and depression). Item-by-item descriptive analyses for the AGS were also performed in order to further characterize the nature of anticipatory grief in the sample. Product-moment correlation coefficients were examined, followed by multivariable linear regression analyses, to assess whether demographic characteristics, caregiving burden, marital quality, or depression were associated with anticipatory grief levels in these caregivers.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The total sample consisted of 55 (75.3%) spousal, 16 (22%) child or child-in-law, and 2 (2.7%) sibling caregivers. Demographic and other background characteristics were similar in the MCI and AD caregiver groups, with two exceptions. Caregivers to persons with MCI were more likely to be spouses and caregivers of persons with AD were more likely to be women (see Table 1). The sample was well-educated, with half having a college degree. They were cognitively intact but the majority reported that they themselves had health conditions leading to impairments in daily activities. While 80% of the sample reported that their income was sufficient to meet their expenses, more than 80% of the sample continued to work and 20% of the sample was struggling financially. A majority of care recipients were men. More than one-third of the care recipients had a concurrent diagnosis of major depressive disorder and nearly one-quarter met criteria for cerebrovascular disease.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N = 73, n (%) or M (± SD)

| Caregiver Characteristics |

Sample (N = 73) |

MCI Caregivers (n = 43) |

AD Caregivers (n = 30) |

t or χ 2 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (sample range = 27-84 yrs old) |

64.88 (11.27) | 66.16 (10.16) |

63.03 (12.64) |

1.12 | .26 |

| Female gender | 57 (78.1) | 30 (69.7) | 27 (90) | 4.22 | .04* |

| Caucasian | 72 (98.6) | 42 (97.6) | 30 (100) | .70 | .40 |

| College degree | 39 (53.4) | 23 (53.4) | 16 (53.3) | .00 | .99 |

| Spouse of care recipient | 55 (75.3) | 36 (83.7) | 19 (63.3) | 3.95 | .04* |

| Years in relationship with care recipient (sample range = 3-60 years) |

34.79 (17.31) | 34.56 (17.81) |

35.12 (16.87) |

−.13 | .89 |

| Lives alone with care recipient | 43 (58.9) | 30 (69.7) | 21 (70.0) | .00 | .98 |

| Income, above $40,000 | 51 (69.9) | 33 (76.7) | 25 (83.3) | .09 | .75 |

| Income is adequate to meet expenses | 58 (79.5) | 35 (81.4) | 26 (86.6) | .35 | .55 |

| Caregiver employed | 61 (83.6) | 26 (60.4) | 15 (50.0) | .78 | .37 |

| MMSE score (sample range 25-30) | 29.42 (1.21) | 29.51 (1.12) | 29.30 (1.34) | .92 | .35 |

| Presence of illness that limits activities | 43 (58.9) | 22 (51.1) | 21 (70.0) | −2.59 | .10 |

| Care Recipient Characteristics | |||||

| Age in years (sample range = 57-97 yrs old) |

75.18 (8.80) | 75.37 (7.18) | 74.90 (10.83) |

.22 | .82 |

| Female gender | 26 (35.6) | 15 (34.8) | 11 (36.6) | .02 | .87 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 27 (36.9) | 18 (41.8) | 9 (30.0) | 1.06 | .30 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 18 (24.6) | 12 (27.9) | 6 (20.0) | .59 | .44 |

| Care recipient employed | 41 (56.3) | 23 (53.4) | 14 (46.6) | .32 | .56 |

Note: p values are two-tailed.

p < .05, df = 71 for continuous variables and 1 for dichotomous variables, MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment, AD = AD, MMSE = Mini Mental Sate Exam

Nature and Level of Anticipatory Grief

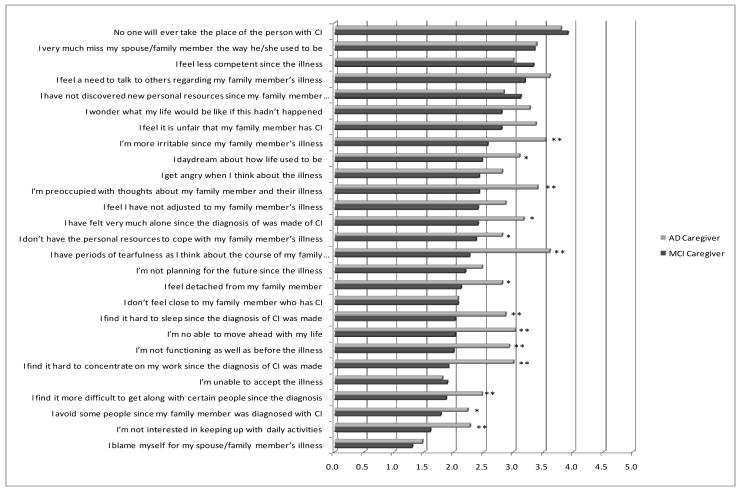

As a group, the sample endorsed a mean anticipatory grief score of 70.1 (± 14.8, the AGS scale can range from 35 to 135). As shown in Table 2, the AD family caregivers reported significantly higher levels of anticipatory grief than MCI family caregivers. Responses on each AGS item are shown separately for the two study groups in Figure 1. There are two noteworthy features of the Figure. First, it indicates which items where endorsed most strongly by each group. AD caregivers most strongly endorsed the item “no one will ever take the place of my spouse/family member in my life” (M = 3.8 ± 1.0), followed by “I have periods of tearfulness” (M = 3.6 ± 1.1) and “I feel a need to talk to others about my family member’s illness (M = 3.6 ± 1.1). MCI caregivers strongly endorsed that “no one will ever take the place of my spouse/family member in my life” (M = 3.9 ± .9), in addition to “I very much miss my family member with cognitive impairment” (M = 3.3 ± 1.2) and “I feel less competent since the illness” (M = 3.3 ± .9). “Blaming myself for my family member’s illness” was not strongly endorsed by either type of caregiver (M = 1.5 ± .7 in AD caregivers and M = 1.3 ± .5 in MCI caregivers).

Table 2.

Differences between MCI and AD Caregiver on measures of Anticipatory Grief, Caregiving Burden, Depression, and Marital Quality (N = 73)

| Variable | Scale Range |

Sample Range | Sample Mean (SD) |

MCI Caregiver Mean (SD) |

AD Caregiver Mean (SD) |

Test of group differences, t |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipatory Grief symptoms |

27-135 | 40-114 | 70.11 (14.78) | 64.49 (11.97) | 78.17 (14.85) | 4.34 | <.001 |

| # of new ADL responsibilities |

0-8 | 0-6 | 0.32 (.98) | 0.14 (.560) | 0.57 (1.35) | −1.85 | .068 |

| # of old ADL responsibilities |

0-8 | 0-7 | 0.45 (1.52) | .72 (1.94) | .07 (.25) | −1.82 | .072 |

| # of new IADL responsibilities |

0-11 | 0-10 | 3.11 (2.95) | 2.07 (.2.73) | 4.60 (2.63) | −3.94 | <.001 |

| # of old IADL responsibilities |

0-11 | 0-9 | 4.11 (2.30) | 2.09 (.31) | 4.20 (2.61) | .278 | .782 |

| Severity of lifestyle constraints |

13-65 | 33-61 | 28.07 (3.64) | 26.49 (3.64) | 30.33 (4.71) | −3.92 | <.001 |

| # of frequent problematic behaviors |

0-215 | 2-118 | 48.11 (26.25) | 39.79 (23.61) | 60.03 (25.55) | −3.48 | .001 |

| Marital Quality (n = 55, df = 53) |

0-151 | 71-144 | 114.24 (14.67) | 112.56 (14.34) | 117.42 (14.94) | .146 | .704 |

| Depression symptoms | 0-60 | 0-38 | 12.05 (9.53) | 10.34 (7.21) | 14.50 (11.81) | −1.86 | .067 |

Note: ADL = activities of daily living, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living, Non-spousal caregivers (n = 18) were excluded from the analyses of marital quality, p values are two-tailed.

Figure 1.

Average AGS Items Responses by Type of Caregiver

The second important element of Figure 1 pertains to the group differences on specific items. The Figure shows that the AD and MCI caregivers showed significant differences in mean scores on 14 (52%) of the 27 AGS items, with AD caregivers endorsing significantly higher scores indicating lack of personal resources to cope with the illness, preoccupation with thoughts of their family member’s illness, daydreaming about their past life together, and feeling very much alone and detached from their family member since the cognitive diagnosis was made. AD caregivers endorsed significantly more difficulty functioning, keeping up with daily activities, and moving ahead with life, as well as more difficulty sleeping and concentrating, being more irritable, tearful, and having difficulty getting along with certain people since the cognitive diagnosis was made. AD and MCI caregivers responded more similarly on the remaining items including anger about the illness or feeling its occurrence was unfair, wanting to talk with others about the illness, and an inability to accept it or plan for the future.

Differences between caregiver groups on caregiver burden, depression and marital quality

The MCI and AD family caregivers endorsed similar levels of caregiving burden with respect to both old and new ADL responsibilities (Table 2). However, AD caregivers reported a greater number of new IADL responsibilities for their family member. They also reported higher levels of lifestyle constraints, and being faced with a larger number of frequently occurring (at least weekly) dementia-related or problematic behaviors. The two caregiver groups were similar on reported marital quality. There was a trend for AD caregivers to report higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Unique contributions of caregiver gender, caregiving burden, and depression to anticipatory grief levels

Because of the exploratory nature of this study, we adopted a very conservative approach to these analyses. Thus, we initially examined each potential correlate’s association with anticipatory grief by computing zero-order correlation coefficients. Variables showing at least a moderately large zero-order relationship (r ≥ 0.3) with anticipatory grief were eligible for inclusion in the multivariate analysis. Seven variables met this criterion: AD (vs. MCI) diagnosis, female gender, a greater number of new ADL responsibilities, a greater number of IADL responsibilities, more lifestyle constraints, a greater number of dementia-related behaviors, and higher depression levels (Table 3, first column).

Table 3.

Results of Correlations and Linear Regression with Anticipatory Grief as the Outcome

| r | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD diagnosis | .458** | .043 | .624 | .535 |

| Gender, female | .365** | −.138 | 2.24 | .028 |

| Presence of illness that limits activities | .365**. | .990 | .492 | .624 |

| Greater # of new ADLs | .470** | .048 | .69 | .487 |

| Greater # of new IADLs | .530** | .226 | 2.99 | .004 |

| More Lifestyle constraints | .712** | .288 | 3.73 | <.000 |

| Greater # of frequently occurring dementia-related behaviors | .691** | .213 | 2.59 | .012 |

| Higher Depression levels | .631** | .339 | 4,73 | <.000 |

| R = .883, F = 28.26(8,64), p < .000 | ||||

Note: ADL = activities of daily living, IADL = instrumental activities of daily living

p < .01 (two-tailed)

Non-spousal caregivers (n = 18) were excluded from the analyses

Results of the regression analyses are presented in the remaining columns of Table 3. Being a female caregiver, higher levels of objective caregiver burden, and a higher depression level each bore independent, statistically significant relationships with anticipatory grief in the sample. Type of caregiver (MCI vs. AD) no longer was a significant correlate of anticipatory grief once these variables were controlled.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore anticipatory grief during the earliest stages of caregiving to individuals with cognitive disease. Other studies have examined anticipatory grief in the context of family dementia caregiving, but none have examined anticipatory grief among family caregivers of persons with MCI. The mean level of anticipatory grief in the current sample (70.11) was higher than the mean of 61.21 reported by Marwit and Mauser, when they examined anticipatory grief among a sample of 87 family AD caregivers who had been providing care an average of 6 years since the dementia diagnosis.32 Building on the work of Mauser and Marwit, where they found a significant inverse relationship between anticipatory grief levels and years since dementia diagnosis,19 our results show that symptoms of anticipatory grief are present even in family caregivers of persons with a diagnosis of mild cognitive deficits, well before they meet criteria for dementia and family members are bearing the heavy burden of caregiving typically associated with AD.

Not surprisingly, depression symptoms levels were correlated with anticipatory grief. However, our findings suggest that anticipatory grief is more than merely an expression of depression; being a female and the day-to-day stressors associated with the caregiving role were also significant correlates of anticipatory grief. Specifically, a greater number of new IADL responsibilities, higher levels of lifestyle constraints, and a greater number of frequently occurring dementia-related behaviors in the care recipient were all independent correlates of anticipatory grief in these relatively new caregivers. Similar to Ott and associates20 marital quality was not significantly associated with anticipatory grief among the subsample of our caregivers who were married.

The higher level of anticipatory grief in our sample may suggest that this grief reaction is highest at the earliest stages of AD caregiving or when the family member begins to provide care and assistance to their loved one with relatively mild cognitive deficits. Alternatively, the higher anticipatory grief levels in the current study may be due to sample’s caregiving situation and exposure to daily stressors; all of our family caregivers lived with the care recipient while only 31% of the adult-child caregivers and 73% of the spousal caregiver lived with the care recipient in the Marwit & Meuser32 study (because many of the care recipients lived in nursing homes, assisted living facilities, or other arrangements). Studies show that the place of residence significantly impacts anticipatory grief levels in family AD caregivers; 20 AD caregivers residing with the care recipient face increased exposure to the burdensome aspects of providing care and assistance to a family member with cognitive impairment.

Consistent with gender differences seen in studies of depression22, and AD caregiving stress33 women in the current sample had higher levels of anticipatory grief than men. Yet, these results are not consistent with studies of anticipatory grief in AD caregivers.34,-36 Since this is the first study examining anticipatory grief in a sample of relatively new family caregivers, the relative “newness” of the cognitive diagnosis may affect women and men differently. Given that the caregiving role develops naturally out of prior patterns of support and assistance exchanged between family members and married individuals, and that women typically assume the caregiving role37 it is possible that female caregivers better understand what the caregiving role entails and feel ill-prepared to cope with unpredictable changes in their patterns of support and assistance. On the other hand, men may not be as aware of what is involved in providing long-term home care to a person with cognitive impairment because they may have less previous caregiving experience and many not anticipate what lies ahead. When we explored item differences by gender, it appeared that women expressed more concern about the impact of caregiving on their life and what the future holds.

Several limitations of the present study must be borne in mind. The small size and composition of the sample introduce potential limitations on generalizability to the population of family caregivers of persons with mild cognitive deficits or newly diagnosed AD. Our sample, although recruited from a clearly defined sampling frame, was predominately white and the caregivers were mostly female. This reflects the population of patients and their caregivers in the ADRC subject Registry. Our use of the Registry enhanced the study’s internal validity because it ensured that all individuals were carefully diagnosed with MCI or AD. However, reliance on the Registry also potentially limits the external validity of the results since such individuals (family caregivers of individuals who have sought a research diagnosis and treatment for their cognitive complaints) may differ from individuals and their family caregivers who have not sought care from an ADRC. By the time the family has sought a diagnosis, friends, family members or health care providers are likely to have noticed that the patient’s cognitive status required a formal evaluation. Thus, while our study captured individuals earlier in the illness trajectory than prior studies, even our sample had already entered the process of coping with cognitive impairment by the time of enrollment. Also, the sample included persons who enrolled in an intervention study focused on family caregivers. It is possible that family members in this study were more challenged by their new caregiving role than persons not enrolling in the larger study.

Further, the generalizability of our findings may also be reduced by our focus on family caregivers who reside with the individual with cognitive impairment. However, we chose to focus on family members that reside with the care recipient because we felt they would be more likely to experience burdens associated with the caregiving role than family members not living with a cognitively impaired person.

Our study’s cross-sectional design limits conclusions regarding the predictive or causal direction of associations between anticipatory grief and other variables. It will be important for future work with larger, more heterogeneous samples, to longitudinally examine whether factors including caregiving burden and depressive symptoms are truly risk factors for anticipatory grief, and whether any effects are independent of, or are influenced by other characteristics of the caregiving dyad (e.g., comorbidity in the care recipient or the care recipient’s perception of his/her own roles and responsibilities.

Lastly, our recruitment rate from the pool of possible participants in this study was relatively low (55%). This response rate may reflect the longitudinal nature of the parent study because the majority of caregivers declining participation cited time and health-related constraints that precluded their involvement in a multi-session intervention. It is noteworthy that our response rate was consistent with rates obtained in other intervention studies in family dementia caregivers.38-40

In sum, despite study limitations, the current study points to the importance of considering anticipatory grief in the context of caregiving for a family member with a new cognitive diagnosis. Providing care to a family member with cognitive impairment is complex psychological experience, and it is possible that the absence of anticipatory grief from conceptualizations of caregiver distress has delayed the development of an accurate understanding of the full experience of caregivers. The emotional responses related to the loss of a healthy spouse or parent, possible changes in his or her personality, and the loss of shared memories and/or plans are rarely considered, and yet, they seem to be important elements of the caregiving experience. The addition of anticipatory grief to conceptual models of caregiving burden may help investigators to clarify the manner by which caregiving stressors lead to negative health outcomes. Since Sanders and Adams34 found that 50% of the variance in depression scores was accounted for by anticipatory grief among a sample of family dementia caregivers, it would be important to determine if depression could be prevented in family caregivers if their anticipatory grief was addressed early in the caregiving role trajectory? Furthermore, studies show that family dementia caregivers with higher levels of anticipatory grief are at heightened risk for symptoms of complicated grief when the care recipient dies. 12-15 Therefore, family caregivers may benefit from education about the nature of anticipatory grief and from opportunities to express their concerns in response to both anticipated and actual losses experienced during the course of caregiving to family members with cognitive impairment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants MH070719, AG05133 and MH52247 from the National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD, and Grant 07-59900 from the Alzheimer’s Association and Dr. Lingler was supported by the Brookdale Foundation Leadership in Aging Fellowship Program.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Theut SK, Jordan L, Ross, et al. Caregiver’s Anticipatory Grief in Dementia: A Pilot Study. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1991;33:113–118. doi: 10.2190/4KYG-J2E1-5KEM-LEBA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rando TA. Anticipatory mourning: A review and critique of the literature. In: Rando T, editor. Clinical dimensions of anticipatory mourning: Theory and Practice in Working with the Dying, Their Loved Ones, and Their Caregivers. Research Press; Champaign, IL: 2000. pp. 17–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rando TA. A comprehensive analysis of anticipatory grief: Perspectives, processes, promises, and problems. In: Rando TA, editor. Loss and Anticipatory Grief. Lexington Books; New York: 1986. pp. 1–36. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holley CK, Mast BT. The impact of anticipatory grief on caregiver burden in dementia caregivers. The Gerontologist. 2009;49:388–396. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marwit SJ, Meuser TM. Development of a short form inventory to assess grief in caregivers of dementia patients. Death Studies. 2005;29:191–205. doi: 10.1080/07481180590916335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farran CJ, Keane-Hagerty E, Salloway S, et al. Finding meaning: An alternative paradigm for Alzheimer’s disease family caregivers. The Gerontologist. 1991;31:483–489. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindgren CL, Connelly CT, Gaspar HL. Grief in spouse and children caregivers of dementia patients. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1999;21:521–537. doi: 10.1177/01939459922044018. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loos CH, Bowd AD. Caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: Some neglected implications of the experience of personal loss and grief. Death Studies. 1997;21:501–514. doi: 10.1080/074811897201840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ponder RJ, Pomeroy EC. The grief of caregivers: How pervasive is it? Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1996;227:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudd MG, Viney LL, Preston CA. The grief experienced by spousal caregivers of dementia patients: The role of place of care of patient and gender of caregiver. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 1999;48:217–240. doi: 10.2190/MGMP-31RQ-9N8M-2AR3. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker RJ, Pomeroy EC. Depression or grief? The experiences of caregivers of persons with dementia. Health & Social Work. 1996;21:247–254. doi: 10.1093/hsw/21.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bass DM, Bowman K, Noelker The influence of caregiving and bereavement support on adjusting to an older relative’s death. The Gerontologist. 1991;31(1):32–42. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullan J. The bereaved caregiver: A prospective study of changes in well-being. The Gerontologist. 1992;32(5):637–683. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.5.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson-Whelan S, Tada Y, MacCallum RC, et al. Long-term caregiving: What happens when it ends? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:573–584. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz R, Boerner K, Shear K, et al. Predictors of complicated grief among dementia caregivers: A prospective study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(8):650–658. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203178.44894.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meuser TM, Marwit SJ, Sanders S. Assessing grief in family caregivers. In: Doka K, editor. Living with Grief: Alszheimer’s Disease. Hospice Foundation of America; Washington, DC: 2004. pp. 170–195. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams KB, Sanders S. Alzheimer’s caregiver differences in experience of loss, grief reactions and depressive symptoms across stage of disease. Dementia. 2004;3:195–210. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butcher HK, Holkup PA, Buckwalter KC. The experience of caring for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2001;23:33–55. doi: 10.1177/019394590102300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meuser TM, Marwit SJ. A comprehensive, stage-sensitive model of grief in dementia caregiving. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:658–670. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ott CH, Sanders S, Kelber ST. Grief and personal growth experience of spouses and adult-child caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(6):798–809. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders S, Corley CS. Are they grieving? A qualitative analysis examining grief in caregivers of individual with Alzheimer’s disease. Social Work and Health. 2003;37:35–53. doi: 10.1300/J010v37n03_03. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: Review and commentary. Journal of Gerontology. 2003;58(3):M240–M265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yee JL, Schulz R. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among caregivers of dementia patients: Comparison of two approaches. The Gerontologist. 2000;40(2):147–164. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Jagust WJ, et al. Neuropsychological characteristics of mild cognitive impairment subgroups. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2006;77:159–165. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.045567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery RJV, Gonyea JG, Hooyman NR. Caregiving and the experience of subjective and objective burden. Fam Relat. 1985;34:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zarit SH, Zarit KE. The Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist - 1987R. Pennsylvania State University; University Park: PA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergman-Evans B. A health profile of spousal Alzheimer’s caregivers: Depression and physical health characteristics. J Psychosocial Nurs Men Health Serv. 1994;32:25–30. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19940901-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruchno RA, Resch NL. Husbands and wives as caregivers: Antecedents of depression and burden. The Gerontologist. 1989;29(2):159–165. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson KM. Predictors of depression among wife caregivers. Nursing Research. 1989;38(6):359–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marwit SJ, Meuser TM. Development and initial validation of an inventory to assess grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(6):751–765. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: A meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2003;58B(2):P112–128. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.p112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilliland G, Fleming SA. Comparison of spousal anticipatory grief and conventional grief. Death Studies. 1998;22:541–569. doi: 10.1080/074811898201399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders S, Adams KB. Grief reactions and depression of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease: Results from a pilot study in an urban setting. Health & Social Work. 2005;30:287–295. doi: 10.1093/hsw/30.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders S, Ott CH, Kelber ST, et al. The experience of high levels of grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Death Studies. 2008;32:495–523. doi: 10.1080/07481180802138845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seltzer M, Li L. The transitions of caregiving: Subjective and objective definitions. The Gerontologist. 1996;36(5):614–626. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallagher-Thompson D, Lovett S, Rose J, et al. Impact of psychoeducational interventions on distressed family caregivers. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 2000;(6):91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 39.King AC, Baumann K, O’Sullivan P, et al. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on physiological, behavioral, and emotional responses to family caregiving: A randomized controlled trial. Journals of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 2002;57A:M26–M36. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.1.m26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toseland RW, McCallion P. Health education groups for caregivers in an HMO. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;57:551–569. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]